Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

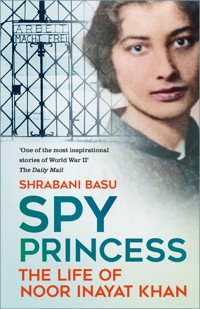

'One of the most inspirational stories of World War II … Reading this book is like watching a butterfly trapped in a net.' – Daily Mail This is the riveting story of Noor Inayat Khan, a descendant of an Indian prince, Tipu Sultan (the Tiger of Mysore), who became a British secret agent for SOE during World War II. In this updated twentieth-anniversary edition of Spy Princess, Shrabani Basu tells the moving story of Noor's life, from her birth in Moscow – where her father was a Sufi preacher – to her capture by the Germans. Noor was one of only three women SOE agents awarded the George Cross and, under torture, revealed nothing, not even her real name. Kept in solitary confinement, her hands and feet chained together, Noor was starved and beaten, but the Germans could not break her spirit. Ten months after she was captured, she was taken to Dachau concentration camp and, on 13 September 1944, she was shot. Her last word was 'Liberté'.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 478

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘An outstanding story. The book is the first authoritative biography of Noor Inayat Khan, very well researched and recreated. It’s crying to be made into a film.’ – Shyam Benegal

‘This is a story not to be missed.’ – Professor M.R.D. Foot

‘One of the most inspirational stories of World War II … Reading this book is like watching a butterfly trapped in a net.’ – The Daily Mail, Christopher Hudson

‘Shrabani Basu has pieced together Noor’s story more fully and reliably than ever before … Thanks to her book, a new generation can grasp what Noor did, and how she did it, with much greater clarity.’ – The Independent, Boyd Tonkin

‘The true life story of Noor Inayat Khan is the stuff legends are made of. It makes compelling reading.’ – Khuswant Singh, eminent historian and columnist

‘A disturbing book. Shrabani Basu approaches her well researched book with a cool-head and perceptive eye.’ – Phillip Knightley, author

‘Her thrilling but sad story is told in this book.’ – Daily Express, Paul Callan

‘This is a story that deserves retelling almost sixty years after the award of a posthumous George Cross … a welcome addition to a field of study that will doubtless continue.’ – Times Literary Supplement, Mark Seaman

‘This moving book tells a powerful, sad story about a girl who found it impossible to remain just a girl.’ – Hindustan Times, Dinesh Seth

‘This is an absorbing true story … the story of a gentle Indian girl in brutal captivity has never been researched so completely.’ – Outlookmagazine, Raja Menon

‘Shrabani Basu pieces together Noor’s life and brings to India a forgotten daughter.’ – The Hindu, Anita Joshua

‘The book makes for compelling reading. Its sensitive narrative makes it a gripping account.’ – The Asian Age, Nayare Ali

‘Sixty years after her death at the hands of the Nazis … the book reveals the life of the war hero that Britain forgot.’ – Eastern Eye, Aditi Khanna

‘Shrabani Basu’s story of Noor Inayat Khan’s life and heroic sacrifice has been painstakingly researched and told with great compassion and deep respect. It is a story of supreme courage worth reading again and again and repeating.’ – Worker’s Publication Centre, Chris Coleman

To my sisters,Nupur and Moushumi

A mermaid once went in a ship

Upon the stormy sea,

And as she sailed along, the

Waves arose and sprung in glee,

For on the ship she hung a lamp

Which gave a light so sweet,

That anyone who saw its glow

With joy was sure to meet.

Noor-un-nisa Inayat Khan (age 14),The Lamp of Joy

Cover illustrations: Noor Inayat Khan. (Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy) Gate at Dachau. (Shrabani Basu)

First published 2006

This twentieth anniversary edition published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Shrabani Basu, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2016, 2019, 2020, 2025

The right of Shrabani Basu to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75246 368 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

The History Press proudly supports

www.treesforlife.org.uk

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

Contents

Map

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Preserving a Legacy

Introduction

Prologue

One Babuli

Two Fazal Manzil

Three Flight and Fight

Four Setting Europe Ablaze

Five Codes and Cover Stories

Six Leaving England

Seven Joining the Circuit

Eight The Fall of Prosper

Nine Poste Madeleine

Ten Prisoner of the Gestapo

Aftermath

Appendices

I Circuits linked to Prosper

II Agents and Resistance members who worked with Noor and the Prosper Circuit

III Chronology

IV Indians awarded the Victoria Cross and the George Cross 1939–1945

Notes

Bibliography

Map of France showing the areas covered by the Prosper and other connected circuits and sub-circuits.

Foreword

Holders of the George Cross are out of the common run; Noor Inayat Khan was even farther out of it than most. She was an Indian princess on her father’s side; her mother was American. She was brought up in Paris, where she wrote and broadcast children’s stories; she had a gentle character and the manners of a lady, but lived in no luxury. She fled to England in 1940, when the Germans invaded France, and worked as a humble wireless operator on Bomber Command’s ground staff. She was plucked up into SOE, volunteered to go back to France in secret, survived for a few months in Paris but got betrayed, and was beaten up and murdered in Dachau.

What was an innocent like this doing with a pistol in her handbag? Why was she sent to France at all, in the teeth of reports that she was quite unfit to go? Why was the prearranged code that showed she was in German hands not believed when she sent it? These are some of the questions this book raises; to some of them it can provide answers.

There are books about her already, one by a close London friend of hers who detested SOE, one in French that does not pretend to be truthful. No other biographer had access, as this author did, to her recently released secret archive, and none till now was a compatriot. Shrabani Basu, London correspondent of a leading Indian news-paper, understands from inside what her heroine must have felt during the world war about the struggle for Indian independence. This is not a story to be missed.

M.R.D. Foot

Nuthampstead

September 2005

Acknowledgements

This book would not have been possible without the encouragement of many people who went out of their way to help me.

I would like to thank Noor’s family, her brothers, Vilayat Inayat Khan and Hidayat Inayat Khan, who despite ill health and pressing work commitments for their Sufi orders, took the time to talk to me and give me details of Noor’s life. Thanks to Hidayat for allowing me generous use of Noor’s stories, poems, documents and family photographs. Sadly, Vilayat did not live to see the publication of the book. Thanks also to Noor’s cousin, Mahmood Youskine, who filled me in with many interesting family details, and to David Harper, Noor’s nephew, for his insights. I would have been lost without the warm and efficient Hamida Verlinden, from the Sufi Headquarters at The Hague, who helped me with Noor’s papers, and Martin Zahir Roehrs, Vilayat’s assistant in Suresnes, who made every meeting possible. Thanks also to Amin Carp from East West Publications at The Hague for his help.

To Professor M.R.D. Foot for meticulously reading each chapter and helping me at every stage, I owe my heartfelt gratitude. I could not have asked for a better guide. I would also like to thank him for writing the foreword to this book.

I am indebted to Jean Overton Fuller, too, for sharing her precious memories of Noor and providing her insights into her friend’s life. I am also grateful to her for allowing me to quote material from her book.

Thanks to Francis Suttill for sharing information with me about his father, Alain Antelme for all his inputs on his uncle and John Marais for sharing his memories of his mother and Noor. Thanks also to Irene Warner (née Salter) for her vivid recollections of Noor and to Emily Hilda Preston for her account of her WAAF days.

In Dachau, I would like to thank my wonderful guide, Maxine Ryder, and Dirk Riedel from the Dachau Museum for his inputs. In Delhi, thanks to Kamini Prakash from the Hope Project for showing me around Inayat Khan’s tomb. In Calcutta, thanks to Mohammed Husain Shah, direct descendant of Tipu Sultan, for telling me about the family history, and in Moscow, thanks to Jelaluddin Sergiei Moskalew for his helpful inputs on Inayat Khan and the birth of Noor.

Thanks also to Phillip Knightley, Michael Dwyer, Heather Williams, Sarah Helm and Chris Moorhouse and John Pitt of the Special Forces Club for all their help and advice. Special thanks to Sumi Tikaram from the FANYs for her constant help and support.

I am grateful to my commissioning editor at Sutton Publishing, Jaqueline Mitchell, for her invaluable guidance, patience and encouragement, and my editors Anne Bennett, Jane Entrican and Hazel Cotton for their meticulous work.

For this twentieth anniversary edition, I am grateful to Gareth Swain, managing director of The History Press, who has always believed in my books and been such a pleasure to work with over the years. Thanks to my editor, Chrissy McMorris, for her patience with all the updates.

Thanks to my daughter, Sanchita, for French translations and Klaas Van Der Hoeven for German translations. And finally, my family for their much needed moral support.

Over the years, I have grown to know Pir Zia Inayat Khan, Noor’s nephew, who now heads the Inayatiya Order. I can’t thank him enough for always keeping me updated with any new discovery from the family archives. Getting a few lines, a poem or a play by Noor is always so thrilling. It is thanks to him that I have been able to update many new details in this edition.

Working on preserving the legacy of Noor Inayat Khan for more than two decades has been a privilege. I would like to thank all those who helped and supported me as I launched the Noor Inayat Khan Memorial Trust. I could not have done it without the support of Zed Cama, Karim Mawji, Sir Julian Lewis, Baroness Christine Crawley, Valerie Vaz, Deepa Patel, Kim Lalli, Kusoom Vadgama, Runi Khan, Smita Tharoor, Aditi Khanna, Radhika Howarth, Rumu Sarah Dey, Charu Shahane, Urmila Rajkhowa, and many many more, too numerous to list here. You know who you are and how grateful I am. Organisations like the FANYS, the RAF Museum, the RAF Club, the British Legion, the Commonwealth War Graves Association and English Heritage have been a great support and have ensured that Noor’s legacy lives on.

Thank you to everyone who has been on this journey with me.

Preserving a Legacy

An update of the last twenty years

On a spring day in 2003, as I sat in The National Archives in London, reading the recently declassified files of Noor Inayat Khan, I knew that I wanted to bring her story to the world. I sat in a secure locked room, the first person to see the documents marked ‘TOP SECRET’. My heart was racing as I read the neatly typed reports – cold and official – with details of her recruitment and training. There were Noor’s own letters written in the neat, slanting handwriting that I would soon grow to recognise, emotional but strong, and her messages from the field. I saw the sheet of paper where she had meticulously practiced her code name ‘Madeleine’. There were the chilling accounts of her arrest and death detailed by her Nazi captors and eyewitnesses. The files contained the letters sent by SOE to her family: Noor was ‘missing in action’, Noor had been ‘brave’, Noor had been on a ‘special mission’. There were the desperate letters from her brother Vilayat to the War Office after the war, asking for news of his sister. He had heard nothing, and their mother was distraught. By now, the tears were pouring down my cheeks. I was glad I was alone in the room.

After the original publication of Spy Princess in 2006, I had an overwhelming reaction from people who had been moved by Noor’s story. Many wrote to me saying there should be a memorial for her. I felt a responsibility to carry on her legacy. I received a call from the Indian Embassy in Paris. The defence minister, Pranab Mukherjee, was visiting Paris in September 2006 and he wanted to pay his respects to Noor. I put him in touch with her family and Mukherjee paid an official visit to her childhood home in Suresnes. He said that Noor’s story of ‘heroism, bravery and sacrifice would always inspire the younger generation’. It was the first formal recognition of Noor Inayat Khan by the country of her ancestors. Later, Mukherjee became the President of India, and said he treasured the copy of Spy Princess in his library. I still have the photo of the late President with Noor’s harp.

The interest in Noor continued, and so did letters from readers suggesting a memorial for her. After all, other colleagues of hers had been honoured with Blue Plaques and memorials. In 2010, I set up the Noor Inayat Khan Memorial Trust in London to campaign for a memorial for Noor. On a November afternoon in 2012, as the leaves turned golden, a memorial bust of Noor Inayat Khan was unveiled by Princess Anne in Gordon Square, Bloomsbury. It was near the house she lived in as a secret agent. Over 400 people packed the square: veterans who had travelled from France; RAF pilots who had flown the agents on their mission; diplomats; and dignitaries. The FANY corps saluted one of their own. People stood outside the iron railings with flowers and bowed heads. It was the first statue of a South Asian woman in a public space in Britain and made us proud. Today, the memorial is visited by people from around the world and is part of the Bloomsbury Peace Tour.

In 2014, Royal Mail contacted me as they wanted to issue a special stamp to honour Noor on the centenary of her birth. The stamp was part of the series called ‘Remarkable Lives’. Later, the British Museum got in touch as they wanted to acquire Noor’s George Cross from her family for their newly refurbished South Asian gallery. The National Portrait Gallery also wanted to acquire a photograph of Noor for their collection. In March 2020, a permanent special digital exhibition on Noor was launched at the Royal Air Force memorial in Runnymede, Surrey. Nearly every museum in London wanted to display something on Noor. In 2020, after a fourteen-year campaign, English Heritage installed a Blue Plaque outside Noor’s London home at 4 Taviton Street. It was the house from where she had left on her fatal mission to France. I was honoured to be asked to unveil it. It was the first Blue Plaque for a woman of South Asian origin in Britain.

Noor’s story has continued to inspire. In 2023, the RAF Club in Piccadilly commissioned a portrait of Noor which was unveiled by Queen Camilla. A room in the Club has been named after her. The same year, Camden Council invited me to inaugurate a new block of social-housing apartments, which was named Noor Inayat Khan House. I was informed that the name was chosen by the residents. In 2024, the RAF Museum acquired Noor’s George Cross. It is displayed beside a Lysander plane in the hangar, along with the pilot’s logbook of the night she was flown to France. His entry on 16 June was simply: ‘Two out’. It meant that two agents had been flown out on that full-moon night. Both agents would not return.

Noor has featured in several children’s books about fantastic women and women spies, and several documentaries. Noor even featured in an episode of Doctor Who, the famous BBC television series, where she helps the Doctor send an important message. In 2025, Noor’s story was featured in a BBC special podcast called History’s Secret Heroes, presented by Helena Bonham Carter.

Nearly every day I receive some enquiry about Noor. It could be a student, an artist or a singer. People have wanted to tell her story in different ways, through music, theatre, books, films and artwork.

In February 2008, two years after the original publication of Spy Princess, a packet dropped through my letter box from a primary school in Manchester. It contained a book called Liberte, brought out by Year-Six children as part of a project. On the cover was a child’s sketch of Noor in her WAAF uniform. Inside were imaginary dialogues and letters composed by the children, including letters Noor may have written from prison. For Noor, this tribute from children would surely have been one of the most precious. To know that her story lives on is truly rewarding.

London, May 2025

Introduction

The lone gardener was working in the June sun clearing the weeds around Fazal Manzil, the childhood home of Noor Inayat Khan. It was a particularly hot day in Paris, a precursor to the heatwave that would sweep Europe in the summer of 2003. From the steps of Fazal Manzil, where the Inayat Khan children had often sat and played, I looked out over the hill towards Paris. The view was blocked by apartment blocks that have mushroomed in Suresnes. It was not quite the sight the children would have seen all those years back.

At eighty-seven, Pir Vilayat was a frail but impressive figure in his white robes. Walking with the help of a stick he took me to the living room with its large bay window. From here one could see the garden and the city beyond. It was in this room that he and Noor had decided that they would go to Britain and join the war effort. A large portrait of their father, Hazrat Inayat Khan, hung on the wall.

‘Every day of my life I think of her. When I go for a walk I think of her, when I feel pain, I think of how much more her pain was, I think of her in chains, I think of her being beaten. When I am cold I think of her, I think of her lying in her cell with hardly any clothes. She is with me every day,’ said Vilayat. It was a moving tribute from a brother.

I had first heard of Noor Inayat Khan many years ago in an article about the contribution of Asians to Britain. I was immediately drawn to the subject and read Jean Overton Fuller’s Noor-un-nisa Inayat Khan, which was fascinating.

As an Indian woman myself, Noor’s life held a natural attraction for me. How a Muslim woman from a conservative spiritual family went on to become a secret agent, working undercover in one of the most dangerous areas during the war, was something I wanted to study in detail. The fact that Jean Overton Fuller’s book had been written over fifty years ago in 1952 made me feel it was worth making another attempt. Noor was an unlikely spy. She was no Mata Hari. Instead she was dreamy, beautiful and gentle, a writer of children’s stories. She was not a crack shot, not endowed with great physical skills and a far cry from any spy novel prototype. Yet she went on to display such courage and fortitude in the field that she was presented the highest civilian honours – the George Cross (UK) and the Croix de Guerre (France). She was one of only three women SOE agents to receive the George Cross, the others being Violette Szabo and Odette Sansom.

The opening of the personal files of SOE agents in 2003 gave me the leads I had been looking for. Though the main players in the field, Noor’s chiefs and associates at SOE – Maurice Buckmaster, Selwyn Jepson, Vera Atkins and Leo Marks – were all dead, I was confident that Noor’s own files and the files of the agents who worked with her in the field would provide fresh material. In an area like the secret service there will always be gaps which cannot be filled. Meetings are held in secret and hardly any records kept. Most of Noor’s colleagues were killed in France, murdered in various concentration camps, and few lived to tell their tale, making the job even more difficult. With the help of Noor’s family – her brothers Vilayat and Hidayat, Jean Overton Fuller’s account, SOE archives and other sources – I have tried to complete the jigsaw of Noor’s life and her final road to death.

While working on this book, I realised that Noor has been romanticised in many earlier accounts with much information about her that is pure fantasy. She has been said to have been recruited while on a tiger-hunt in India. Her father, an Indian Sufi mystic, is said to have been close to Rasputin and invited by him to Russia to give spiritual advice to Tsar Nicholas II. She is said to have been born in the Kremlin. None of this is true, though much of it has been repeated in many seminal books on the SOE.

Noor was an international person: Indian, French and British at the same time. However, she is better known in France than in Britain or India. In France she is a heroine. They know her as Madeleine of the Resistance and every year a military band plays outside her childhood home on VE (Victory in Europe) Day, on 8 May. A square in Suresnes has been named Cours Madeleine after her. She has inspired a best-selling novel La Princesse Oubliée (The Forgotten Princess) by Laurent Joffrin, which has also been translated into German. Joffrin has given her lovers she did not have and taken her through paths she did not walk; it is a work of fiction.

Sixty years after the war, Noor’s vision and courage are inspirational. I hope my book brings the story of Noor Inayat Khan to a new generation for whom the sacrifices made for freedom are already becoming a footnote in history.

Shrabani Basu

November 2005

Prologue

11 September 1944, Pforzheim prison, Germany

Her hands and feet chained together, classified as a ‘very dangerous prisoner’, Noor Inayat Khan stared defiantly at her German captors. Her dark eyes flashed at them as they tried to break her resistance. They had virtually starved her, keeping her on a diet of potato peel soup, struck her frail body with blows and subjected her to the dreaded Gestapo interrogation, asking her again and again for the names of her colleagues and her security checks. She had said nothing.

But at night, in the confines of her cell, she gave vent to her anger and pain. Fellow prisoners in neighbouring cells could hear her sobbing softly.

Kept in solitary confinement, unable to feed or clean herself, Noor’s mind wandered off to her childhood days. The dark German cell seemed a world away from her childhood home in France where her father sang his Sufi songs in the evening and Noor played with her younger brothers and sister. Little ‘Babuli’, as her father used to call her, had come a long way.

She was now Nora Baker, a British spy, being tortured and interrogated in a German cell. Ten months had gone by since she had been captured in France. She had a chain binding her hands together and another binding her feet. There was a third chain that linked her hands to her feet so she could not stand straight.

Her father’s words kept coming back to her, his gentle Sufi philosophy, but also his reminder to her that she was an Indian princess with the blood of Tipu Sultan in her veins. She called out silently to Abba to give her strength. And the great-great-great-granddaughter of Tipu Sultan, the Tiger of Mysore, held on, though she knew the end was near.

At 6.15 that evening the men from the Gestapo entered her cell again. Noor was told it was time to go. ‘I am leaving,’ she scrawled in a shaky hand on her food bowl and smuggled it out to some fellow French women prisoners. It was her last note. Still chained, Noor was led out of her cell and taken to the office.

At the prison office, Noor was met by three officials of the Karlsruhe Gestapo. She was driven in handcuffs to Karlsruhe prison, 20 miles away.

12 September 1944, Karlsruhe prison, Germany

Early in the morning, around 2 a.m., Noor met three of her fellow spies, Eliane Plewman, Madeleine Damerment and Yolande Beekman, at the Commandant’s office. Noor had trained with Yolande in England. Josef Gmeiner, head of the Karlsruhe Gestapo, told them they were being moved. Still in handcuffs, the four young women were driven in Gmeiner’s car to Bruchsal Junction to catch the express train to Dachau, 200 miles away. Their escorting officers, Max Wassmer and Christian Ott, gave them some bread and sausages for the journey.

After the confines of the prison, it felt good to be outdoors. There was a brief halt at Stuttgart where they boarded another train for Munich. The young women were given window seats in the same carriage and allowed to talk to one another. Naturally, they chatted animatedly. It was a pleasure for them to meet colleagues and speak English again. One of the women had some English cigarettes on her which she passed around. When they were finished, the German officer offered them some German cigarettes which they also smoked. It almost felt like a picnic.

On the way there was an air raid. The train pulled up at Geisslingen and waited for 2 hours. The women stayed calm as Allied aircraft flew overhead, even though they could hear the sound of the bombs. It had been three months since the Allies had landed in Normandy. The girls exchanged what information they had about the invasion.

At Munich they changed trains again. Their escorting officers made them board a local train for Dachau. It was midnight when the train finally reached the siding there. Still in handcuffs, the prisoners were ordered to walk the 2 kilometres to Dachau concentration camp.

13 September 1944, Dachau concentration camp, Germany

The air was cold as the young women prisoners struggled towards the camp with their bags. The first chilling sight was of the camp’s searchlights, visible from afar. As the beams swept the area, the new arrivals could see the high walls of the camp, and the barbed wire. Built in 1933, it was the first concentration camp to be constructed by Hitler, close to his base in Munich, where thousands of Jews, gypsies and prisoners of war were to meet their deaths. Other camps, including Auschwitz, were built later with Dachau as the model.

Noor and her colleagues were taken through the main gate of the camp inscribed with the words Arbeit Macht Frei (Work Will Make You Free). The words were ironic because few walked free from Dachau. Over 30,000 people were exterminated here between 1933 and 1945.

As they entered the camp, they could see the line of barracks on their left. Inside, in rows of dirty bunk beds, lay the inmates, crammed like cattle, half starved and thinly clad, inhabiting a world somewhere between the living and the dead. Along the side of the barracks ran the electric fences covered with barbed wire and the deep trench which prisoners were warned not to cross. Further down was the crematorium. Outside it stood a single post with an iron hook. Here the Gestapo hanged their prisoners, often stringing them up from meat hooks with piano wire and leaving them to die slowly.

The four young women were taken to the main registration office and then led to their cells where they were locked up separately. In the early hours of the morning, the SS guards dragged Madeleine Damerment, Eliane Plewman and Yolande Beekman from their cells, marched them past the barracks to the crematorium and shot them through the back of their necks.

For Noor, it was to be a long night. As the prisoner who had been labelled ‘highly dangerous’, she was singled out for further torture. The Germans entered her cell, slapped her brutally and called her names. Then they stripped her. Once again she bore it silently. All through the night they kicked her with their thick leather boots, savaging her frail body. As dawn broke over the death camp, Noor lay on the floor battered and bleeding but still defiant. An SS soldier ordered her to kneel and pushed his pistol against her head.

‘Liberté!’ shouted Noor, as he shot her at point blank range. Her weak and fragile body crumpled on the floor. She was only thirty.

Almost immediately, Noor’s body was dragged to the crematorium and thrown into the oven. Minutes later eyewitnesses saw smoke billowing out of the crematorium chimneys. Back in England that night, her mother and brother both had the same dream. Noor appeared to them in uniform, her happy face surrounded by blue light. She told them she was free.

ONE

Babuli

The story of Noor Inayat Khan began on New Year’s Day in Moscow in 1914. As the frozen Moskva river gleamed in the reflected light of the green and purple domes of the Kremlin, a baby girl was born in the Vusoko Petrovsky monastery, a short distance from the Kremlin. The proud father was the Indian Sufi preacher Hazrat Inayat Khan, and the mother a petite American woman with flowing golden hair, Ora Ray Baker. They named their little girl Noor-un-nisa, meaning ‘light of womanhood’. She was given the title of Pirzadi (daughter of the Pir). At home their precious little bundle was simply called Babuli.

Inayat Khan and Ora Ray Baker had arrived in the city of Moscow in 1913. For Inayat it had been a long journey from his home town in sunny Baroda in western India to the snowy splendour of the Russian capital. He had left India on the instructions of his teacher Syed Abu Hashem Madani to take Sufism to the west. Inayat was the grandson of Maula Baksh, the founder of the Faculty of Music at the University of Baroda, and Casimebi, the granddaughter of Tipu Sultan, the eighteenth-century ruler of Mysore. The family enjoyed a proud heritage as descendants of the Tiger of Mysore, as Tipu Sultan was known, who had fought bravely against the British.

Yet the family did not publicise this royal heritage, for political reasons. After Tipu Sultan had been killed fighting the British on the battlefield of Seringapatam in 1799, his family was forcibly removed from Mysore to prevent further rebellion in that area. The son of Tipu Sultan was also subsequently defeated and killed in Delhi fighting the British during the uprising in Vellore in 1806. According to family legend his daughter, the 14-year-old princess Casimebi, was taken to safety by two faithful servants – Sultan Khan Sharif and Pir Khan Sharif. They were the sons of an officer who had served under Tipu Sultan. The princess was taken secretly to Mysore and her true identity concealed. Because she was of royal descent, Casimebi could marry only a person of noble standing, who carried royal honours and titles.1

As luck would have it, Inayat Khan’s grandfather, Maula Baksh, went to Mysore in 1860 and sang at a competition before the Maharaja that lasted for eleven days. A skilled singer in both the North Indian classical style and the South Indian Carnatic classical style, Maula Baksh won the competition. The delighted Maharaja of Mysore presented him with a kallagi (turban ornament), sarpesh (turban), chatra (large umbrella), chamar (fly whisk) and the right to have a servant walk in front to announce him. When Maula Baksh received these emblems of royalty, the two retainers secretly arranged his marriage to Princess Casimebi.

Maula Baksh was now told of the secret of the princess’s ancestry. Casimebi’s heritage was talked about only in whispers (lest the British discover that the retainers had hidden one of Tipu’s descendants). Maula Baksh and Casimebi then moved to Baroda (also known as Vadodara) in Gujarat at the invitation of the city’s ruler. Here Maula Baksh started the Gayanshala or Music Academy, overlooking the lake, where it still stands.

Inayat’s father, Rahmat Khan, a musician from the Punjab, came to Baroda and started teaching at the Gayanshala. He married one of Maula Baksh’s daughters, Khatijabi, and moved into Maula Baksh’s large family house on the edge of the town with its stables, large courtyard and separate women’s quarters. It was in Baroda that Inayat Khan was born to Rahmat Khan and Khatijabi on 5 July 1882. Soon two more sons were born, Maheboob Khan and Musharraf Khan.

The house of Maula Baksh was an open one where all religions were tolerated and music rang out from each corner. Meals for forty to fifty people were cooked in the kitchen every day. The liberal, tolerant atmosphere of his maternal grandfather’s house was to have a major influence on Inayat Khan and on his daughter, Noor.

Inayat Khan soon began to teach at the Gayanshala and travelled extensively, giving concerts in Nepal, Hyderabad and Calcutta. In Hyderabad he played for the Nizam and was initiated into Sufism by Syed Abu Hashem Madani. His teacher advised him to combine his music and his philosophy in order to bring about a better understanding between East and West.

After the death of his father Rahmat Khan, Inayat Khan decided to follow his teacher’s advice. He had received an invitation to play in New York and he wrote to his brother Maheboob Khan and cousin Mohammed Khan asking them if they wanted to join him. They agreed immediately.

‘Dost chalo’ (Friend, let us go), Inayat Khan told his brother and his cousin as he used to do when they were young.2 The men packed their instruments and sailed from Bombay in a small Italian ship in September 1910.

New York came as a shock to the musicians from Baroda. They were used to the leisurely life of the Gayanshala and the hectic pace of Manhattan took time to get used to. So did the weather and the food, but gradually they settled into their new surroundings. The group called themselves the Royal Musicians of Hindustan and began giving concerts at Columbia University. Soon they were recruited by the dancer Ruth St Denis, who took them on a tour of the country starting in Chicago.

At a lecture in the Ramakrishna Mission Ashram in San Francisco, California, Inayat Khan met a young woman called Ora Ray Baker. She was born in Albuquerque, New Mexico, on 8 May 1888, the youngest of three sisters and one brother. Ora’s father was Eurastus Warren Baker, who was a cattle farmer and later became a lawyer and newspaper editor. Her mother was Alletta (Etta) Margaret Hiatt, born to a distinguished family from Switzerland that had immigrated to Pennsylvania in the United States in 1733. Her parents led separate lives, and Ora was brought up by her half-brother, Dr Pierre Bernard, who had travelled widely in India, sat at the feet of gurus and became an authority on yoga and Sanskrit. He had a large Sanskrit library and founded the New York Sanskrit College in 1910. Ora came from a wealthy family with interest in law, medicine and politics. Her uncle was a senator and her grandfather was Erasmus Warner Baker, a solicitor. Ora is believed to have been a distant cousin of Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of the Christian Science movement. Though Ora lived largely in Manhattan and New Jersey, she travelled extensively with Pierre visiting Seattle, Kansas and San Francisco. It was her half-brother’s interest in India that would take Ora to San Francisco to attend a lecture by one Prof. Inayat Khan. It would change her life forever.

The night before the lecture, Ora dreamt of an Eastern mystic holding her in his arms. They had both soared above the sea into the skies. The next day she met Inayat Khan. It was as if her dream had been prophetic. Ora watched Inayat Khan play the veena and heard him speak. She was completely mesmerised. Seeing her interest, her brother Pierre suggested she learn the veena from Inayat Khan. Over lessons and philosophical exchanges, the two soon fell in love.

But Inayat Khan knew his future was uncertain. He told Ora Ray that he was a dervish and did not know where his next meal would come from. Ora Ray Baker’s family did not approve of the match, and neither did Inayat Khan’s brothers. He told her they could write to each other and she could join him only when she had secured the consent of her family or when she came of age. In the spring of 1912, leaving behind his address with Ora Ray, Inayat set sail with his brothers once again, this time for England, where he had an invitation to play at a musical convention. His younger brother, Musharraf Khan, joined him in New York before they left. After a mixed reception in England, the brothers moved to France in September 1912 in the belief that the French would be more inclined to appreciate their music.

Parisians were fascinated by all things oriental and soon the Royal Musicians of Hindustan were busy giving concerts, lessons and lectures. The famous dancer Mata Hari, the rage of the Paris nightclubs, engaged them as part of her troupe. She called them ‘mon orchestre’ and had herself photographed with them in the garden of her house in Neuilly, with herself in the foreground striking a dance pose and the Royal Musicians of Hindustan standing behind her in all their finery, looking amused and slightly awkward. Ironically, many years later, Inayat Khan’s daughter, Noor Inayat Khan, would also be a secret agent, though not quite in the Mata Hari mould. Like Mata Hari, who was executed by a firing squad in the Bois de Vincennes, Noor too would be executed.

In Paris, Inayat Khan was introduced to the leading French actor and director Lucien Guitry, who asked the group to take part in an Eastern-themed show called Kismet. Before long, the Royal Musicians of Hindustan were playing before the cream of French society. They met Edmond Bailly, the actress Sarah Bernhardt, the sculptor Auguste Rodin, the dancer Isadora Duncan and many other prominent people. During this time Inayat Khan also met the composer Claude Debussy, who encouraged the group by his understanding and appreciation of Indian music.

Meanwhile Ora Ray Baker had given up trying to persuade her brother to accept her relationship with Inayat Khan, and she wrote to tell Inayat that she was coming to France to join him. Her ship arrived in Antwerp where he met her and they left immediately for England. On the ferry they met another Indian who said he would perform a religious rite to solemnise the union.

On 20 March 1913, Inayat Khan married Ora Ray Baker at the civil register office at St Giles, London. They rented a place at 4 Torrington Square, Bloomsbury, and began a new life in England. Ora Ray Baker was given the new name Amina Sharada Begum. Inayat chose the name Sharada after Ma Sharada, wife of the Indian saint Ramakrishna Paramhans, in whose ashram in San Francisco Inayat Khan had first met his wife. Ora Ray’s brother never forgave her and she severed all links with her family. She started wearing a golden sari to match her husband’s golden robe and even wore a veil. Inayat himself had never asked her to wear Indian clothes but the Begum insisted she was doing it of her own free will. She said she had always envied the seclusion enjoyed by the women of the East.3

The couple received many social invitations and Amina Begum handled all her husband’s correspondence, as well as organising his schedule and travels. In London they met the Indian poet Sarojini Naidu, a firm supporter of Indian independence, who was to accompany Gandhi on his famous Salt March of 1930. Inayat would practise the Indian stringed instrument known as the veena in the evenings and sing in the mornings. He often spent hours meditating at night.

In 1913 Inayat Khan and his group received an invitation to play in Russia. The invitation came from Maxim’s, the Moscow nightclub, which wanted an Oriental night. The musicians did not like what they saw of Maxim’s. The drunkenness and debauchery that prevailed there was alien to the men and they wanted to leave, but Inayat Khan persuaded them to stay and honour their commitment.

Moscow soon grew on Inayat Khan. He loved the intellectual atmosphere of the city and, despite the freezing climate, spent some of the happiest days of his career there. He realised that the people who went to Maxim’s also frequented the concerts and salons and that Moscow was actually a deeply cultured city. He found in the people of Moscow the same sort of warmth that he experienced back home in India. In turn, Inayat Khan made an immediate impression and soon had among his friends Sergei Tolstoy, the son of Leo Tolstoy, who became the representative of the musical section of the Sufi Order in Moscow.

It was in Moscow that Inayat Khan made one of the first attempts to combine eastern and western music. He chose seventeen ragas and adapted them to a play based on an episode from Kalidasa’s Shakuntala. Sergei Tolstoy and a friend, Vladimir Pohl, harmonised the Indian melodies and even scored them for a small orchestra. The theme was the liberation of the soul.4

Moscow, with its blue-green oriental domes, luxury and sophistication combined with poverty, reminded Inayat Khan of India. He rode in an open sleigh and met many priests and monks. The city was seething with rebellion at that time as the Tsar was perceived as weak and under the influence of his wife and courtiers. Communists and anarchists fanned the people’s discontent. The secret police spied on people everywhere. Even Inayat Khan and his brothers were followed to their concert one day. Later the person shadowing them became embarrassed and introduced himself as Henry Balakin. He confessed that he had been sent to watch over them. When Inayat Khan reassured him and said he understood why he did it, Balakin became his mureed or disciple.

At this time the family lived in a four- or five-bedroom house called the House of Obidin on the corner of Petrovka Street and Krapivenski. It was just opposite the Vusoko Petrovsky monastery and about 1.5 kilometres from the Kremlin. A modestly furnished place, it provided enough room for Inayat, his young wife and his three brothers.

The couple’s first daughter, Noor, was born in Moscow at 10.15 p.m. on 1 January 1914. Noor was very special to Inayat Khan, being his firstborn. Like his father and grandfather before him, Inayat Khan reached out to his new baby through music. He would sing to her and carry her around as he gently lulled her to sleep.

Baby Noor’s nurse had some rather unusual habits, however. She was a strong Tartar woman who horrified Amina Begum by giving her daughter black coffee to drink and scrubbing her with a brush made of stiff bristles as a sort of massage. She also started binding Noor’s feet to keep them small as was the Chinese-Tartar custom. It was the nurse who gave Noor the name of Babuli (Turco-Tartar for ‘father’s child’).5

Apart from her idiosyncratic ways, which were alien to Amina Begum, the widowed nurse nevertheless was a considerable support to the household. She had a 16-year-old girl, who Musharraf fell in love with and wanted to marry, proposing that both mother and daughter become part of the family and travel with them. Amina Begum strongly opposed the match, causing some conflict in the Inayat Khan household.6

When Noor was forty days old, Inayat Khan invited some friends and admirers to his house to attend a ceremony for Noor. The invitees included a group of Russian students who had met Inayat Khan at Maxim’s. One of the students, Yevgenia Yurievna Spasskaya, later described the event in rapt tones:

At last a velvet portiere opened and entering from the next room … I don’t know what others saw, but I imagined that I saw Nesterov’s Blue Madonna: against the background of the dark-red velvet portiere she stood slim, fair, in a blue scarf wrapped around her slender body, a young mother with a tiny tawny baby in her hands.7

The sight of the fragile Amina Begum in her blue sari with her head covered and flowing golden hair standing next to the tall stately figure of Inayat Khan had completely captivated Spasskaya. During the ceremony Amina Begum sat in an armchair holding baby Noor while the other brothers and musicians came up to her one by one, bowed low, sang a greeting and gave her a gift. Then the tabla player, Ramaswami, who had met Inayat Khan in New York and joined the group, sang a joyful song that he had composed especially for mother and baby, which amused everybody. This was followed by more music as all the brothers sang and a feast of Indian sweets and food prepared by an Indian cook was served.

Baby Noor sat quietly in her mother’s lap through all the singing and a proud Inayat Khan told the students that she was already a theosophist.

Though Inayat Khan may have met Tsar Nicholas II through his friend Sergei Tolstoy, it is not certain whether Inayat Khan ever met the Russian mystic Rasputin. It is possible that he met him at St Petersburg, because Inayat Khan is known to have been in the city from 13 May till the end of the month.8

Meanwhile the political atmosphere in Moscow was becoming highly charged and one of the Tsar’s officers advised Inayat Khan to leave the city. Sergei Tolstoy loaned them a sledge and they prepared to leave. But on the day they decided to go, riots broke out and the people put up a barricade, barring their path. As the excited crowds gathered around their sledge, Inayat Khan took baby Noor from his wife’s arms and held her up. So impressive was the sight of Inayat Khan in his golden yellow robes holding up the tiny baby that the crowd immediately fell silent and drew back the barricade.

The family made its way to St Petersburg and then to France. The Royal Musicians of Hindustan had an invitation to play at the International Music Congress in Paris in June. Ramaswami decided to return to India but the other musicians played at the Music Congress and stayed in Paris for a while, giving concerts and lectures. But soon war broke out in Europe. In August 1914, with German cannons pointing at Paris, Inayat Khan decided to take the family to London. Here he would be based for the next six years as Europe was torn by the First World War.

London in the war years was a hard environment for the family. Having drawn capacity audiences in Moscow and Paris, Inayat Khan now faced half-empty halls for the first few months. Everyone was preoccupied with the war. Noor was to spend the first few years of her life in considerable poverty and hardship. Yet her father’s spirit, his calmness and meditative outlook, clearly imbued her with strength.

In London, Inayat Khan sang for Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and brought tears to his eyes. He sang for Indian soldiers who lay injured in hospital and at charity concerts to raise funds for war widows. In June 1915 the Royal Musicians of Hindustan played in the opera Lakme and got good reviews.9

But though Indians backed the war effort, the British government was suspicious of Inayat Khan and kept a close watch on him. Once at a charity concert for Indian widows and orphans, Inayat Khan was overcome by emotion and started to sing patriotic Indian songs reminding his countrymen of their glorious heritage. He received thunderous applause, which made the British even more wary. The invitations to charity concerts died out and the family was left with hardly any income.

Musharraf Khan, in desperation, started looking for menial jobs as a road worker and Maheboob Khan started giving private lessons. Mohammed Khan accepted music hall engagements singing European arias and ballads. Amina Begum found it hard to run the large household. Coming from an affluent family herself it was particularly difficult for her. She also discovered to her dismay the prejudice against mixed marriages in British society and got rid of her veil as she felt it aroused unnecessary attention. The family survived on a meagre ration of plain rice and daal every day. There were days when there was only bread on the table.

Inayat Khan remained calm through these trying times. He practised his veena and sang to Noor every day. The family at this time moved to 86 Ladbroke Road in London and it was at this address that Inayat founded the Sufi Order in England in the autumn of 1915. The movement’s symbol was a winged heart inscribed with the star and crescent. Soon there was more reason to celebrate. On 19 June 1916, a son was born to Inayat Khan and Amina Begum. They named him Vilayat, meaning Chief. He was given the title of Pirzade (son of the Pir). Noor called him bhaijaan (brother dear).

Little Noor adored her baby brother. He soon became her closest friend, and would remain so throughout her life. Though poor, the children were brought up in an atmosphere of loving warmth. Their earliest memories were of their father carrying them in his arms and singing them to sleep. Sometimes when they could not sleep at nights, he would sit down by their bed and sing to them. Often the children lay awake just to hear his songs. Inayat Khan believed that children of this age were so sensitive that they could feel the warmth of his music as he sang to them. He himself had been taught by Maula Baksh about the effect of music on the body and its role in maintaining health through resonance and rhythm.10 He would never allow the children to be woken abruptly and often sang softly to wake them up.

Meanwhile, the war had a deep impact on Inayat Khan and he was very disturbed by the constant death and devastation. He tried to help people by simply talking about death and focusing their minds on prayer and brotherhood to make their suffering more bearable. In the difficult years in London, Inayat Khan became a murshid (teacher) himself, travelling and lecturing. Chapters of the Sufi Order were set up in 1916 in Brighton and in Harrogate in 1917. Gradually the halls started filling up as people sought spiritual answers during the war years.

In 1917 the family moved into a large house in 29 Gordon Square financed by the Sufis. Over the years two more children were born to Inayat Khan and Amina Begum: Hidayat, a boy, and Khair-un-nisa, a girl. Inayat called his second daughter Mamuli (mother’s child). To Noor, Vilayat was bhaijaan, Hidayat was bhaiyajaan, and Khair was Mamuli or Mams. Noor, little more than a toddler herself, mothered them all.

The family spent happier times in Gordon Square. Though money was still scarce, the house was buzzing with activity and the four children kept Amina Begum’s hands full. Noor was a delicate child, dreamy and sensitive. When she heard that children in Russia had nothing to eat she took it to heart, although she was only four. She began demanding chocolates from the adults, and as soon as she got one she would leave the room. Later her parents found she had a big box full of chocolates in her room, which she was collecting for the Russian children.

Noor would play with Vilayat in the Square and believed that she had seen fairies there. She even told her family that she talked to the little creatures who lived in the flowers and bushes. They did not question her, but the children in the neighbourhood did. They laughed at Noor’s tales of fairies and it upset her so much that she stopped seeing fairies after that. Even when Noor grew up she loved fairies and would often sketch them in cards and write about them in stories.

The children lived in a somewhat unreal world. The house was full of visiting Sufis and they were often left to themselves. One day a child came and told Noor and Vilayat that Santa Claus did not exist. This upset both children and they rushed to their father and asked him for the truth. Inayat told them: ‘When something exists in the imagination of anybody, you can be sure there is a plane on which it has real existence.’11 All of which probably meant nothing to the two children, but both felt they had been told something very profound and left feeling quite elated.

As the guns of war were silenced in Europe, the family settled in to life in London. But the Home Office was still suspicious of Inayat Khan. The fact that Inayat Khan had met Mahatma Gandhi and nationalist leaders like Sarojini Naidu made them keep him under supervision. Nationalism was growing in the overseas Indian community at this time as the Jallianwala Bagh massacre12 in Amritsar had had a strong impact on all Indians. Inayat Khan’s friend, the poet Rabindranath Tagore, had returned his knighthood in protest.

Some Muslim friends of Inayat Khan invited him to preside over the Anjuman Islam, a committee to bring Muslims and non-Muslims together. But a member of the society sent out letters to collect money for a charity for Muslim orphans without registering the society and the Anjuman Islam became the subject of a police investigation. It was eventually cleared of shady dealings but the ill-feelings remained. Inayat Khan’s house and movements were watched.

A faithful mureed in Southampton, Miss Dowland, advised him to leave England. She sent him money to tide over the financial crisis. Another mureed in South Africa also sent them money to relocate and a third devotee offered them his empty summer house in Tremblaye, a village in France.

In the spring of 1920, the family of Inayat Khan prepared to move once again. Vilayat was only four at the time. All he remembered was the small boat and how everyone was seasick.13 Noor was just six, clinging to her mother and her younger brothers and sister as the family crossed the Channel again. Inayat held his veena and looked out at the sea. The war in Europe was over. He wondered what the future would hold for his young family.

TWO

Fazal Manzil

Noor and her family soon settled into their house in the small village of Tremblaye, north of Paris. Vilayat remembered it as a damp place with no heating and no food. Tremblaye was hardly a place to give Indian concerts and soon the family were once again in dire financial straits.

Inayat Khan left his wife and children behind and travelled to Geneva where some Sufi disciples helped him with generous donations. By now Hazrat Inayat Khan was an established murshid and everywhere he went, his mureeds helped him set up centres. The family struggled through the winter alone but early in 1921 Inayat Khan returned to Tremblaye and took them to Wissous, another small town to the south of Paris. The family enjoyed better days in Wissous. The house belonged to a naval officer and stood on the edge of the village overlooking fields. Inayat would meditate in the garden early in the morning while the children played around him. Later, he would play the veena and sing. At Wissous, Hazrat Inayat Khan held a summer camp for his close followers. In the evening the mureeds would gather in the large living room. The brothers played their instruments and there was an atmosphere of tranquillity.

In the spring of 1922, one of Hazrat Inayat Khan’s devoted mureeds, a rich Dutch widow named Madame Egeling, offered to buy a house for the family. One day, as Inayat Khan and his disciples were walking in the Bois de Boulogne in Paris, they decided to cross the river and climb the hill at Suresnes. Suddenly, a large house surrounded by trees caught Inayat Khan’s attention. ‘It must be here!’ he exclaimed.1 The house, luckily, was for sale. Situated a few miles from the centre of Paris, near the Longchamps racecourse, it was perfect for the family. From the upper windows one could see the lights of the city and the Eiffel Tower in the distance, and on a clear day there was a view of Sacré Coeur and the Seine winding down towards the Cathedral of Notre Dame.