Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

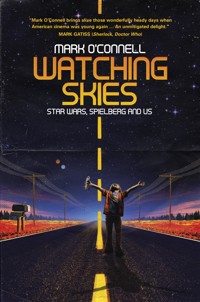

Mark O'Connell didn't want to be Luke Skywalker, He wanted to be one of the mop-haired kids on the Star Wars toy commercials. And he would have done it had his parents had better pine furniture and a condo in California. Star Wars, Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T. The Extra Terrestrial, Raiders of the Lost Ark and Superman didn't just change cinema – they made lasting highways into our childhoods, toy boxes and video stores like never before. In Watching Skies, O'Connell pilots a gilded X-Wing flight through that shared universe of bedroom remakes of Return of the Jedi, close encounters with Christopher Reeve, sticker album swaps, the trauma of losing an entire Stars Wars figure collection and honeymooning on Amity Island. From the author of Catching Bullets – Memoirs of a Bond Fan, Watching Skies is a timely hologram from all our memory systems. It is about how George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, a shark, two motherships, some gremlins, ghostbusters and a man of steel jumper a whole generation to hyperspace.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 532

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Mark O’Connell, 2018

All images © Mark O’Connell

The right of Mark O’Connell to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8615 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

For Elliot – who lifts life like a BMX bike flying against the moon.

Contents

About the Author

The Opening Crawl

1 The California Express

2 The Great Muppet Opener

3 Toys. Toys!

4 Obi-Wan Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

5 He Came to Me Too

6 A Bright Centre to the Universe

7 Plastic Fantastic

8 The First Last Jedi

9 That’s Clark, Nice

10 Cousins of Steel

11 If You’ve Got It, Haunt It

12 The TV People

13 Raiders of the Lost Movie Art

14 AT-AT on a Hoth Tin Roof

15 Dante’s Movie Inferno

16 Once More with Freeling

17 The Sith Element

18 Darth Becomes Him

19 In Martha’s Vineyard, Not Far from the Car

20 To the Spaceship

Closing Titles

Bibliography

About the Author

Mark O’Connell is an award-winning writer, author and Bond fan. As a comedy writer he has written for a wide range of actors, performers, and media. As a pop culture pundit, he has written and guested for Variety, Sky Movies, The Times, The Guardian, OUT magazine, Channel Four, Five, various news outlets and across the BBC. He was one of the official storytellers of London 2012, owns one tenth of a BAFTA, is also a travel writer and lives in England with his husband. He is the author of Catching Bullets: Memoirs of a Bond Fan.

markoconnell.co.uk

Twitter / @Mark0Connell

Instagram / MarkOConnellWriter

It is a dark time for the Hollywood System. A team of rebel filmmakers have managed to steal the secret plans to the SEVENTIES and have already begun a sequence of films with enough power to change cinema.

On the frozen planet of Britain, a young boy needs releasing from the vile clutches of boring toys, no siblings and a lack of home video.

In an attempt to rescue the boy and the childhoods of all like him, the rebel filmmakers are dispatching their movies into the farthest reaches of cinema with a special mission to kids the world over – watch the skies …

The canary-yellow road lines of the Pacific Coast Highway stretch into the horizon like the opening crawl of a Star Wars movie. As the steady trail of cars, camper vans, motorbikes and cyclists threads along Highway 1 towards San Francisco, the cobalt blue skies of California in August match the Pacific’s waves beneath. In a SUV rental the size of a space shuttle, my partner and I are not only pondering how the Pacific Coast Highway is hardly wide enough for a SUV rental the size of a space shuttle – we are reflecting too on the Los Angeles we have left behind, and the America we have already found.

We had seen the Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, where black and white photographs of the 1977 queues for Star Wars became nearly as iconic as the film itself; we very nearly threw water over a dining Daryl Hannah’s feet, just to see if she still had the Splash mermaid’s tail and a sense of humour; I confused Al Pacino with my Limey accent and got the stony Corleone stare for my troubles; we wandered the very Paramount sound stages that housed The Godfather, Chinatown, Rosemary’s Baby and Star Trek III: The Search For Spock; we had lunch at the Walt Disney Studios and a sneaky peek at its archives – despite nearly crashing said SUV rental into a security booth, much to the guards’ amusement – and two-time Bond actress and Octopussy herself Maud Adams took us on a charming tour of Hollywood and Beverly Hills in exchange for some home improvement advice and a trip to various lumber yards. Our SUV was soon christened the USS Maud – in part tribute to its interstellar dimensions, but also because its satnav voice reminded us of the Octopussy actress and my ‘co-star’ on my previous book, Catching Bullets: Memoirs of a Bond Fan.

Driving the line to San Francisco and the home of Star Wars.

Trying to soundtrack our journey with the Californian sounds of Mama Cass, Joan Baez, The Byrds, Bread and the movie sounds of John Barry, Bernard Herrmann and John Williams, we travel along the very highways that were themselves the locations of new wave game-changers such as Easy Rider, Chinatown, Play Misty For Me, Dirty Harry, Harold and Maude, American Graffiti and The Graduate. It soon becomes ever-apparent that America is the one country whose cinematic reputation precedes it more than any other. Everything we think we know of America came from and continues to come from its movies. Station wagons, yellow school buses, cop cars, neon Coca-Cola signs, Cape Cod beach fences, protest marches on DC, newspaper stands, spinning wind pumps, the leaves of fall lapping white picket fences, lemonade stands, surfboards, top loading washing machines, baseball gloves, groceries in brown paper bags, piles of mash potato, mailboxes on poles, railroad crossings and all-night diners. These accoutrements of Americana were not just commonplace to us because we went there. They were commonplace because the movies came to us.

Taking the 101 to San Francisco, California.

We are driving to San Francisco – the counterpulse city home of queer culture, Hitchcock, Pixar Animation, a thriving movie fan scene to maybe match no other, Industrial Light & Magic, abundant independent movie festivals, the brassy paddle steamer that is the vintage Castro Theatre movie palace, Dirty Harry, The Conversation, A View to a Kill, Milk, The Towering Inferno, Vertigo, Peaches Christ’s wild and canny celebrations of cult and un-cult classics, all manner of underground and overground cinema, all manner of movie and media technology, and both the spiritual and production home of Star Wars and Lucasfilm Ltd. Having passed the shipping container cranes at the Port of Oakland – and how local legend loves to mythically suggest their gargantuan four-legged frames straddling the horizon were George Lucas’s inspiration for the AT-ATs in The Empire Strikes Back – we are soon crossing the Bay Bridge into San Francisco. With that disaster movie stalwart that is the Golden Gate Bridge on our distant right, I glance to where the near-mythical Skywalker Ranch might be hiding in the Marin Headlands, and where in the city’s Presidio Park the 23-acre headquarters of Lucasfilm Ltd and legendary visual effects house Industrial Light & Magic are now based.

Minutes later, we are taking a left into Folsom Street and driving past the very South of Market stretch where a late-1960s act of anti-Hollywood defiance saw a new generation of Northern Californian filmmakers begin to change the face of American and mainstream cinema forever. It was here, on the second floor of a warehouse at 827 Folsom Street, that moviemakers George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, John Korty, Walter Murch, Caleb Deschanel, Matthew Robbins, Willard Huyck, Howard Kazanjian, John Milius and others set up the first incarnation of American Zoetrope. A response to the counterculture revolutions happening all around them, Zoetrope’s agenda was to cultivate and support a moviemaking independence from Hollywood and its withering studio hierarchies. It was here amidst the recording studios, gay clubs, bathhouses, leather bars, stoner enclaves and experimental arts spaces of Folsom that Francis Ford Coppola worked on the post-production of The Rain People (1969) and pal George Lucas took his University of Southern California’s graduation film project, Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB, and developed it into 1971’s THX 1138 and the feature film whose genesis and DNA was vital to his future far, far away galaxies.

827 Folsom, San Francisco – the site where George Lucas and his moviemaking pals began to change US cinema in a now long-gone warehouse.

The Coppola Club II – the Sentinel Building at 916 Kearney Street and the home of American Zoetrope since 1971.

I am not sure when my love affair with America quite began. But I know what started it. The movies. And not just any movies. It was the second golden age of American cinema – the unplanned, often anti-establishment, and cinematically rich new wave of 1970s creativity whose first globally recognised and mainstream poster boy was Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975). As the classical Hollywood system, its studios, stars and thinking slowly caved in on themselves amid a late-1960s of shifting demographics, budgets and tastes, the likes of Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), Easy Rider (1969), Midnight Cowboy (1969), Woodstock (1970), Five Easy Pieces (1970) and The Last Picture Show (1971) all laid vital foundation stones to an upcoming decade of movie hope and independence. Here was a new generation of movie-soaked filmmakers who did not just want a cinema that made us look inwards. They wanted us to look outwards. And skywards. It was now the time of Star Wars, Superman: The Movie, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Poltergeist, Gremlins, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Ghostbusters, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Alien, The Omen, Superman II, Jaws 2, The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi. It was the era where the shark-skin suits and Pomade-slicked hair of old Hollywood were replaced by the fake sharks, jeans, long hair, checked shirts and branded baseball caps of a film-savvy younger guard. To movie-mad kids growing up on that frozen planet of Britain, the bearded triumvirate of Steven Spielberg, George Lucas and John Williams were household names before we could even spell our own household’s name. Phrases and figures like ILM, Skywalker Ranch, Frank Oz, Margot Kidder, Richard Donner, JoBeth Williams, Amity Island, Chief Brody, Miss Teschmacher, Joe Dante, Lynn Stalmaster, Lawrence Kasdan, the Well of the Souls, Carlo Rambaldi, Tom Mankiewicz, the Daily Planet, Mike Fenton, the Salkinds, Rick Baker, CBS/Fox video, The Freelings, Ralph McQuarrie, Dennis Muren and Kathleen Kennedy were all part and parcel of our movie-watching parlance and playground chat. I could not tell you the line-up for England’s 1982 World Cup hopes, but I could soon name at least three sound designers and production artists on films I hadn’t seen yet.

Taking its cue from Watch the Skies – the original working title of what became 1977’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (which itself was a closing phrase from the 1951 sci-fi classic The Thing From Another Planet) – Watching Skies: Star Wars, Spielberg and Us is about American cinema of the 1970s and early 1980s. It is about how one era’s cinematic output became a new rich age for a new Hollywood order whose key players were wilfully operating outside of itself. It is about how the mass spectatorship for these movies was soon offset by the very personal inroads into our childhoods, our cultural reference points, our most treasured movie house memories, our vacation routes and our toy boxes. It is about a cinematic sky that experienced a magnificent dawn with 1975’s Jaws and a glorious sundown with 1984’s Ghostbusters and Gremlins. It is a small window of cinema. But in barely a decade, that small window let in a hell of a lot of cinematic light. With the original Star Wars trilogy as both crowning glory and First Family, this book intends to reconsider a rich portfolio of key familiar titles, and the personal stamps they put on our movie souls as they continue to shape big and vital cinema to this day.

This is not about chronology. Just as we experience all cinema in different ways, in different times and in different orders, the stars in this movie firmament are dotted in different directions. This is not a volume about the extended universes of Star Wars or the elongated adventures of fan favourites with names like Jarab Puke or Putt Ferlangi. This is not going to happily tell you how the carved images of C-3PO and R2-D2 are visible on the Ark of the Covenant in Raiders of the Lost Ark, that Return of the Jedi was originally called Revenge of the Jedi or that Tom Selleck was originally cast as both Indiana Jones and the mum in E.T. This is not about fan theories of Kylo Ren being Admiral Ackbar’s great-nephew. Vice Admiral Holdo being Poe Dameron’s mother, or Mon Mothma actually being Emperor Palpatine’s drag queen alias. This is not even going to spend too much page space sticking voodoo pins into a Jar Jar Binks doll. Watching Skies is about how these films work as movies. And experiences. It is not about the making of Raiders of the Lost Ark or trivia about a broken mechanical shark in Jaws. For many reasons, the movies of this era are still the benchmarks, the forerunners, and the templates. These movies were not just a fresh dawn of storytelling and storytelling wizardry. They marked the beginning of a new thinking towards release patterns, the seasons of the movie year, how films were promoted, how films became franchises, the home cinema market, merchandising, how such films influenced the filmmakers that followed and how the movies now renovate, repair and reboot themselves. And with the now forty-year-old A New Hope and Close Encounters of the Third Kind officially middle-aged movies, Lucasfilm and Disney continue bringing that far, far away galaxy just that bit closer with a new Star Wars trilogy and standalone adventures; The Duffer Brothers’ Stranger Things goes from strength to strength on television; Marvel Studios’ Guardians of the Galaxy spins on an axis of Walkmans, Knight Rider, mixtapes and 1970s vinyl; a new genre of fan-led documentaries are looking at the affection and dedication these films engender on a lifetime (Raiders!, Elstree 1976, Back in Time and For The Love of Spock), the rise of Secret Cinema and the new immersive and wholly communal ways to honour our cinematic linchpins; and Steven Spielberg’s Ready Player One is now uploaded onto movie screens, with its coyly pitched post, post, post-modern tale of a dystopian society where a social and gameplay currency centres on 1980s pop cultural references and nods to the cinema started by the likes of Lucas, Donner and Spielberg. It is as good a time as any to skip school, pick up those BMX bikes and watch the skies again.

With the Hollywood sign looking on from Mount Lee, Paramount Studio’s Stage 30 and 31 – the production home of one of 1970s cinema’s key players, Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather.

As my previous book, Catching Bullets, is a very personal tale of watching James Bond movies, Watching Skies is a universal and affectionate tale about the personal remembrances stuck in all our R2 units’ memory systems. It is about being one of the Star Wars generation. It is about how cinema was part of our formative years like never before. Before there was Bond for this writer, there was Star Wars and those titles that swiftly followed its movie jump to lightspeed. So maybe Watching Skies is a Star Wars prequel. What can go wrong?!

1980. It’s time to play the music. It’s time to light the lights. That was probably my earliest memory. Of anything. Well, that and the soaked socks and leather sandals I got when my 4-year-old foot slipped into a tiny garden pond and I thought I was going to drown in a 1970s information film warning of the vagaries of unattended ponds. Before I was a Bond fan or a Star Wars fan or an Indiana Jones fan or a Superman fan, I was a Muppets fan. My favourite toy was a very well-worn Kermit the Frog bendy toy made of rubber with properly unsafe 1970s wire limbs, and my 6th birthday cake had Henson’s characters carefully iced all over it. The Muppets and the Peanuts gang were my world. Every Friday night at 7 p.m. I would hesitate in the bath with one ear on the lounge TV until Gonzo’s trumpet blast heralded that The Muppet Show’s opening theme had finished. The overture and its bounding blue monsters, orange-haired ghouls in tuxedos and the lank-haired Miss Piggy quietly terrified this 5-year-old. But once Kermit came out to invite me into Jim Henson’s fuzzy Beatnik universe, I was there, dripping wet and ready to meticulously eat the one black cherry yoghurt from the Keymarkets’ multi-pack I would always dutifully save for a Friday night. Black cherry yoghurts were always the best.

The Muppets and the Peanuts gang were my first touchstones to that place called America. The Snoopy TV shows and comic strips underpinned a 1960s sense of West Coast Americana – of white picket fences, milk and cookies, baseball mounds and a sunny afterschool Californian suburbia. But it also served up a valuable cynicism, lessons in how the world does not play fair, a sense of comedy, a presentation of broken families and the faceless vagaries and fears of adulthood. Meanwhile, on the other side of the American map, Jim Henson and The Muppet Show were mining a whole East Coast heritage of burlesque, cabaret and vaudeville. That mix of West Coast Americana and a folky, East Coast Beat Generation was prescient stuff for this 1980s kid.

I was born five years earlier, at the very end of September 1975. Rebel Without a Cause was being shown by BBC1 – to no doubt commemorate James Dean, who had died on a stretch of road off the Pacific Coast Highway twenty years to the day – and the famous ‘Thrilla in Manilla’ boxing match was about to kick off between Ali and Frazier. Sydney Pollack’s Three Days of the Condor was number 1 at the American box office, and was the first film all summer to knock Jaws off the top spot it had stayed at since its US release on 20 June 1975. In California, George Lucas was drafting and designing Adventures of the Starkiller – a little-known film which eventually evolved into a very well-known film called Star Wars. Steven Spielberg was prepping a UFO movie called Watch the Skies. Bond director Guy Hamilton was developing a movie of Superman. And Richard Donner was just a few miles down the rural Surrey roads, about to start filming The Omen.

Breakfast at Kermit’s and a late 1970s childhood of Spielberg kid hair, great cousins and wood panelling.

I was an only child. And I still am. I lived with my mum and dad and our three dogs in a sleepy house-lined lane just outside a Surrey village called Cranleigh. Mum was a primary school teacher and my dad worked in the airline cargo business. Unbeknownst to me at the time, the movies were already a lot nearer my life than I would realise. In fact, very near. It was a few years yet before I got to fully appreciate how my grandfather, Jimmy O’Connell, had already spent the majority of his working life in and around the movies by the time I was 5 years old and starting school. Jimmy worked for James Bond producer Albert R. Broccoli and the 007 creative house, EON Productions. He was the Broccoli family’s chauffeur, house-sitter, car-sitter, child guardian and more. His intermittent jaunts to Los Angeles and the former Broccoli family home in Beverly Hills, and his more regular trips back and forth from South Audley Street in London’s Mayfair to Buckinghamshire’s Pinewood Studios, put him in the eye of a moviemaking world he was always notoriously quiet about. The Broccolis were never anything but supportive and looked after Jimmy way beyond his retirement. On my first trip to Los Angeles many years later, and before I took in the movie culture and history of the town, my partner and I went with the lead actress from the first Bond film I ever saw – 1983’s Octopussy – to pay brief tribute to the Broccolis, my grandfather, the house he sometimes looked after and the movie maelstrom that is Hollywood. Cinema has the power to do that. It gets very personal, very quickly.

The first film I saw at the cinema was a Disney re-release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. It was December 1980 at the Guildford Odeon. I was 5 years old. I remember the sadness of the titular heroine alone in her glass coffin with a bereft Dopey waiting nearby, and being transfixed by the animated light reflections bouncing off the cigarette-stained ivory of the art deco interiors of the 1935-built cinema. But by that time, America itself had already come to my home in a rather curious and random fashion. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter’s hand-picked American ambassador to Britain, his entourage and Stars-and-Stripes-bearing car twice visited our humble Surrey bungalow. So far, so very Robert Thorn and The Omen. The brilliantly named Kingman Brewster Jr. had not long finished his modernising tenure as president of Yale University, which of course irritated a few vocal and less progressive folks such as President Richard Nixon and the then Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger. The Brewsters were now looking for a new family pet and my mum had already built up a sound reputation for breeding Golden Retrievers. Unfortunately, the Anglo-Irish politics of late-1970s Britain and the mainland activities of the IRA meant the O’Connell surname was somewhat of a dicey one where American dignitaries and friends of President Carter with the highest diplomatic position outside of America were concerned. With all the blacked-out security of a lurking government car in E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Brewster Jr. had to remain inside his as the security staff came indoors instead, had a cup of tea, met the litter and then picked a puppy which Kingman and his wife took home to his palatial address in Regent’s Park a few weeks later. There is every likelihood that at least one American president met one of our dogs. And ten dollars says it wasn’t Richard Nixon.

Our parents’ post-war, baby boomer generation learnt about America through rock and roll, chewing gum and hamburgers. Theirs was a generation where they went to the movies and found America through music, the radio, denim and vinyl. Mine was when the movies and America came to us – a time when home video and film merchandise took on a bedspread, figurine and collector’s sticker album life of its own. It all changed when a great white shark terrorised the waters of Cape Cod, the comfort zones of Universal Pictures’ financiers and movie house owners who thought they knew how summer audiences worked. Instead of the musicals, westerns, Biblical epics and social dramas of our parents’ generation’s moviegoing, now America was presenting its movie self via more adventure, fantasy and science fiction. The age-old sense of spectacle is unaltered. The widescreen might and wonder of cinema does not change in the 1970s. The background cameo tributes to Pinocchio (1941) and The Ten Commandments (1956) in Close Encounters of the Third Kind are tribute and testimony to that. Yet, maybe science fiction and the fantasy movie came of age in the decade of Watergate, various energy panics, the three-day week and Dolby Stereo. It certainly moved from the communistic allegories and nuclear age fears of our parents’ teen years and its B-movie heyday.

The first inkling I had of the science fiction genre was not from the cinema at all. It was from our local big town’s shopping centre, The Friary. Guildford’s gleaming new hive of retail and adjoined parking had just opened in 1980. Like all brick-interior British shopping centres housing the futuristic likes of C&A, Clockhouse, Athena, Tammy Girl and Tandy, ours was also held up as the zenith of suburban shopping. However, in the December of 1981 it was briefly known as ‘Zondor’. Such was the futuristic vision of the newly opened shopping centre and its revolutionary system of escalators, that BBC space opera Blake’s 7 came to town to shoot a sequence for its penultimate episode, ‘Warlord’. Blake’s 7 was one of British television’s reactions to Star Wars. It was a sort of human Pigs in Space – which to date had been the only other future world I had experienced before. And even that unnerved me. I had a long-standing problem with Henson’s pig puppets and their human-like eyes. It took me a long time to not break out in a cold sweat whenever felt-covered swine did Rodgers and Hammerstein chorus numbers in unison.

The Friary shopping centre’s pivotal role in the 1981 episode of Blake’s 7 depicted bad Federation soldiers picking off spaced-out civilians on their way up and down the escalators. Having shopped there again recently, it was quite an apt forecast. Wearing curiously familiar Tatooine moisture farmer robes, said victims were no doubt heading to the sales at Clockhouse and Tammy Girl when they were so cruelly lasered to death. Despite being too young to properly take in Guildford’s brief moment of sci-fi immortality, I do recall a subsequent ‘make’ on British kids’ TV stalwart, Blue Peter. By way of the standard disclaimer ‘get a grown up to help you’, host Janet Ellis instructed viewers in how to make a Blake’s 7 teleporter wrist bangle thing out of a plastic soda bottle. I tried to make one. But it just looked like a plastic soda bottle bangle from a show that had actually ended a few years before but the repeats were doing the rounds again.

Like a lot of science fiction and its need to reflect current times through its various futures, Guildford’s cameo in Blake’s 7 was fairly metaphorical for life in Britain at the time. The ‘Winter of Discontent’ of 1979 and its government-blaming trade union strikes were still a recent, sore memory. As young British kids entering the 1980s with only three television channels, one landline telephone under the stairs, three flavours of crisps, one Thatcher in Parliament and nine and a half months of grey weather a year, we were constantly being trained to be fearful of British electricity pylons, Bonfire Night sparklers and crossing a suburban road anywhere near a parked Bedford van. Oh, and stagnant pools of water housing hidden shopping trolleys just waiting to grab the feet of passing young kids. For a time, we only ever had publicly-funded kids’ TV shows demonstrating just how to make film and television merchandise from the household rubbish our refuse trucks were on strike from collecting. All I had was a height chart from The Magic Roundabout and a Muppets annual, in which I had folded over any pages featuring any felt pigs with creepy eyes.

Because of all that drudgery, warning and pallid living, we would get extremely excited about new space-age developments within our reach, like escalators and pedestrian walkways that would go over traffic lanes. No wonder Blake’s 7 thought Guildford was the future – albeit a dystopian Home Counties one whose shops only sold beige slacks and which all closed on a Sunday and at lunchtime on a Wednesday. Thinking about it, science fiction really had it in for our neck of the planet. Not only was Guildford twinned with some tyrannical alien state called Zondor, but The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1978) and Douglas Adams made sure lead character Ford Prefect initially claimed he was from Guildford for maximum dullard effect, Doctor Who and the Silurians (1970) did location battle on our local heathland whilst the Doctor blocked the traffic in nearby Godalming with his faithful souped-up yellow car Bessie, and one of the key fathers of science fiction, H. G. Wells himself, was more than happy for The War of the Worlds (1897) and its alien invasions to trash nearby Woking and the surrounding towns and villages.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind

1977. A fearless small boy’s imagination and toys run riot when midnight alien visitors lay siege to his Alabama home – engulfing the skies around his house in dazzling orange illuminations and his single mother in total fear.

The cinematic skies of 1982 were rich with sci-fi landmarks and immortal game-changers. Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Blade Runner, First Blood, The Thing, Poltergeist, The Dark Crystal, Tootsie, Rocky III, Das Boot, Conan the Barbarian, The Sword and the Sorcerer, The Evil Dead, Max Mad 2, Tron and of course E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial all took their first bow in 1982. It was a year marked by the Falklands War, the Greenham Common nuclear protests, Dynasty, Princess Diana’s unique fashion sense and the space shuttle’s first manned mission. But if any year of my childhood should have a big canary-yellow Irwin Allen disaster movie font over its foyer, then it is ‘1982!’ Just like the disaster movie genre itself, my parents’ marriage didn’t quite survive the turn into the new decade. And just like any young kid watching The Towering Inferno or The Poseidon Adventure on TV one Sunday afternoon, I don’t really remember the perilous build-up or the dangerous cracks appearing – just the final-act fireworks and capsized emotions. We had gone from being the Brody family of Jaws to the Kramers of Kramer Vs Kramer – whose original Avery Corman novel my mum had a well-worn copy of, complete with the then obligatory ‘8 pages of film scenes’ which may have accounted for my Meryl Streep obsession and scrapbook in later years.

The summer of 1982 had hardly got off to a good start. Not only did the Pope not actually visit our school and bless our new television room and its plush diocese-financed carpet as the very wild rumours had promised, I was then snubbed by Admiral James T. Kirk and the entire crew of the Enterprise. A neighbour pal was having a Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan cinema birthday trip I clearly wasn’t invited to, as the other boys from the road and their packed lunches carpooled into various cars without me. In hindsight, maybe I should have waved them off wearing a Starfleet insignia pin rather than an ‘I heart Pope John Paul II’ badge we had to buy at school, no doubt to prove our allegiance to the good ship Jesus. I certainly recall that the 1981 assassination attempt on the Pope’s life guaranteed us Catholic foot soldiers attended the neighbouring church for days and weeks to pray for his soul, safety and new popemobile. I have still not forgiven the nuns for leading no such vigils a year later, when Captain Spock also put his life on the line behind some protective glass for a much greater good. The birthday party snub was the first of a few at that time, one of the possible side effects of the Surrey mum circuit thinking the kid from the broken – or breaking – home was damaged goods. Or something like that.

It is worth remembering that in 1982, it was only those cinematic skies and their screens where we could watch our films. Us junior school kids of Thatcher’s Britain may well have been positioned in a glorious Kessel Run of Reaganite-era movies and American culture – but this was not an era in which we could actually see those films. Not at will, anyway. Home videos and the machines to play them on were still a form of wizardry, that had yet to fully infiltrate all the homes of Britain with those three TV channels, prudishly timed closedowns and daily warnings about turning off your television sets before going to bed. There were no Star Wars boxsets, Sky Movies HD on demand or anniversary Blu-ray editions of Jaws. There were no teaser trailers, video blogs or live streamed interview panels at Comic Con. It was an era when the quality of a film was judged by watching it and its story skies, not the online hit rate or reaction of a first photo or still from a teaser’s teaser. We would only know of a new movie via a half-page black and white ad in Look-In magazine or some crude greyscale image of a lightsaber in the newspaper flanked by, ‘Now showing at the Odeon Marble Arch and leading cinemas throughout the country.’ But no one would actually tell you just where those ‘leading cinemas’ were.

One of the greatest movie summers of all time, and the nearest I got to it was some repeat matinee screenings of The Cat from Outer Space (1978) at the 1936 monoplex that was our trusted local cinema, the Cranleigh Regal. To be fair, a great many of those summer American releases didn’t reach British shores until the autumn – or ‘the fall’, as the movie campaigns like to call it. But in 1982, if you didn’t have a cousin with a mate whose neighbour had a video player, then you were pretty much like Han Solo in A New Hope – digging your heels in and resisting the very notion that such home entertainment sorcery existed. Us Spielberg-generation sky kids were still part of the Old Republic – bound to television schedulers, TV holiday premieres, theatrical re-releases and birthday cinema party invites. Going to the movies was still a rare treat – even rarer if, like me, you had detaching parents and no siblings around to up the odds of Panda-orange-fuelled family trips down the cinema. The cracks were certainly showing in my mum and dad’s lives together. Kramer Vs Kramer was not far off the reality – minus, perhaps, the Central Park trike rides, badly made French toast, five Oscars and Vivaldi.

When the summer holidays came, Mum and I left our Surrey bungalow and flew up to Clydebank to stay with family in her childhood home near the River Clyde and the John Brown shipbuilding history my grandfather and his siblings had once been such a proud part of. My aunt and uncle had moved into my grandmother’s house since the early death of my grandfather, James. Not only had they created an upstairs lounge – which blew my 1982 mind with its upstairs stereo, upstairs sofas, upstairs coffee percolator and upstairs television – when it came to new home technology, my uncle Tommy was somewhat of a pioneering Glaswegian Jedi Knight, minus the man bun. My older cousins, Maureen and Mark – I was known as ‘Wee Mark’ – had cassette players in their rooms, knew all about Dr Pepper and owned a Grandstand 6000 Colour video game centre. Not only did it understandably boast ‘10 Games’ including the groundbreaking likes of Gridball, Soccer, Basketball and Tennis – which was a Pong rip-off in all but name – it also had the added analogue glory of two attached joysticks and a console slider score tracker.

Attaching wires and things to the back of a TV and having a picture that was not BBC1, BBC2 or ITV – which you were controlling – was tantamount to joining the dark side. Admittedly, for quite a while I thought Ceefax was some CIA computer system only our TV had access to. Not that I wasn’t at the cutting edge of gaming technology myself in 1982. My other uncle, Gerald, had recently sent me a newly-released Donkey Kong Jr. Game & Watch all the way from Australia. Not only was this pocket-sized console offering a Game A and Game B option, it also had an inbuilt alarm clock and stand. I may have secretly wanted the Snoopy Tennis Game & Watch with its rather fetching puce veneer and ability to see Snoopy ace like Billie Jean King, but to this day Donkey Kong Jr. remains the only Nintendo product I have ever owned – even if it was ultimately easier to use a Grandmaster 6000 to hack into the Pentagon and play WarGames than to learn how to swing for that sodding jungle key at the end.

My aunt and uncle’s previous house was once owned by one of the inventors of television itself, John Logie Baird. It seemed apt that the evolution of television and technology had now made them the first in our family to own a video recorder and the Polaroid VHS cassettes to go with it. Possibly the first Logie-Baird-style demonstration of a video player I’d ever witnessed was during that August 1982 visit, when my uncle put on a video of my cousin Mark appearing on a recent episode of BBC kids’ show Why Don’t You?. Imagine a kids’ TV summer show set in the basement of an asbestos-ridden warehouse with the dullest regionally-selected kids known to humanity sat on hay bales, picking through a weekly mailbag rich with suggestions as to how you can really shake up your pineapple and cheese party snacks by replacing the pineapple with more cheese, viewers’ letters detailing such anecdotal gold as the time Janet from Hartlepool once pulled the beard of a vicar as a baby, and my cousin Mark nervously guiding us through Glasgow’s turn-of-the-century trams. Yes, that was Why Don’t You? – and the first time I jumped to home-video hyperspace was watching cousin Mark nervously extoll the virtues of reversible tram seats on behalf of the Scottish Trams Union Society. Looking very much like a teenager from Jaws 2, minus the sailing injuries and Cape Cod tan, Mark did a grand job in making Why Don’t You? almost watchable as the nation waited for Battle of the Planets to kick in afterwards. I was quietly agog at how the very fabric of time itself could be altered by fast-forwarding a programme to any point in history – well, the history of time between Hong Kong Phooey and Battle of the Planets one August morning in 1982. I was equally transfixed by the lights and buttons on the video recorder and how the ‘tape’ would vanish inside the machine only to re-emerge like a big piece of Pez candy. Our PYE push-button TV set back home was a rather sedate, mahogany box of mono sound, three channels and a repository for all those kitschy pottery vases our parents seemed compelled to buy on holiday in the 1970s.

My uncle Tommy was certainly the family flag bearer for all things video, stereo, sound and vision. He would have magazines lying about with centre spreads on the Dolby advancements in movie sound and which movies were available for ‘home rental’ that month. I didn’t even know what ‘home rental’ was. But it was at this time during this summer visit that I first encountered Close Encounters of the Third Kind in a magazine, and became quietly transfixed by the stills of the ‘mothership’ and that iconic tsunami of blue light, orange beams and silhouettes. I had started to watch television that didn’t always star the Muppets or Sesame Street. Already landmark titles like Close Encounters and Star Wars were circling our worlds and our TV culture. I was also an only child. Too often – and gloriously so – my siblings or sleepover pals would be TV shows. They were certainly my breakfast, teatime and a lot of school holidays. My mum’s regular insistence on watching Little House on the Prairie evolved into Dallas and then I got hooked into The Dukes of Hazzard, CHiPS, Diff’rent Strokes and repeats of Wonder Woman and The Incredible Hulk. Letters like NBC, CBS and ABC became as familiar as Thames TV, LWT and ATV. We could memorise the television schedules and when CHiPS was broadcast on a Saturday afternoon quicker than we did our times tables. Well, I could. But I was having a Larry Wilcox fixation at the time that would immediately switch into a Bo Duke one on the other channel an hour later.

Very soon, we were the generation who knelt at the altar of Aaron Spelling, Glen A. Larson, Stephen J. Cannell and all the American TV production houses whose end credit logos we could recite in our sleep. We were also not averse to taking our movie and TV play out of the lounge and into the back gardens, side alleys and suburban streets of Thatcher’s Britain. It would almost always involve bikes and the hierarchy of who owned a racer versus those on a Chopper. Before the 1982 school holidays had started – and energised by American teatime TV shows like The Red Hand Gang and CHiPS – a bunch of us neighbourhood kids had recently, and somewhat controversially, been exploring an abandoned industrial estate and its scope for wheelies, jumps and screeching halts. It was a school night and we all very quickly made the mistake of ignoring our parental teatime curfews. That magic witching hour of dusk, the ochre sundowns, our flared Lee denim on the pedals and our indie locks, was a heady mix when the suburban Californian adventures of TV shows like The Red Hand Gang had emancipated us to venture a bit further and a bit later. When we finally could not eke out another minute, we returned home only to find a line of our concerned parents stood like FBI agents mounting a roadblock. And there was no director’s cut replacing their fury with walkie-talkies, as befitted the twentieth anniversary modifications of 1982’s E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. At least three of the fuming mums looked ready to throw down a stinger strip, and one dad was one glare away from using tear gas on our Rebel formation.

Never underestimate the wonder of a bike, summer evenings, movie-inspired adventures and having Spielberg kid hair.

All in all, I had not had much luck when it came to bike play. A year before, in the July of 1981, my 5-year-old self was cautioned by a policeman on the night of Prince Charles and Lady Diana’s wedding for failing to use lights, reflectors and a red, white and blue plastic bowler hat in a built-up area. And an acne-ridden, glue-sniffing kid once threw a high-speed apple at me from his racer and nearly knocked the white plastic basket off my first bike. He was probably quite justified in said attack on my bike basket and he probably wasn’t actually a glue-sniffer. But anyone in early-1980s Britain who was a local enemy with bad acne must of course be a Copydex-snorting fiend. Grange Hill and those terrifying 1980s anti-fun information ads saw to that.

But here in Glasgow another bike incident was to inadvertently set me on a path to the Force. An early summer evening visit with my mum and cousins to pals of theirs resulted in an accident that finally set in motion a series of events which made me a Star Wars kid. Just as the visual effects touches were no doubt being done on Return of the Jedi and its speeder bike chase back in California, I did a backie on the seat of a 16-year-old boy’s racer and within a few metres tore my right ankle open in the pedals. He was mortified and shaking as he carried me valiantly into the nearest hospital in an adult-fearing panic. His name was Paul Logan, a talented musician and the older teen brother straight out of a 1970s Spielberg movie with his dark mop of hair, skinny T-shirt and Dunlop sneakers. He was also one of my first misplaced crushes. Or maybe it was just the mindful older brother figure I had always wanted, but seemed to only have for just one evening. He stayed with me as the doctors sewed up my ankle, and later carried me in his arms, in what felt like the dead of night, to my grandmother’s house in Old Kilpatrick. Two summers later, when I was back in Glasgow and Supergirl was 1984’s summer cinematic obsession, I overheard my cousin Maureen mention how Paul Logan had drowned in a diving accident. It was news that dropped like a quiet geranium petal that only I noticed.

Such an injury was obviously a badge of honour to a nearly-7-year-old. My mum was less keen, possibly kicking herself and a bit more agitated that it happened on her watch at a marital time which had little house space for more drama. Going outside was, of course, now limited. Maybe it was now time to avail myself of Tommy’s magical upstairs VHS emporium. One particular title still fascinating me was Close Encounters of the Third Kind, its talk of motherships, UFOs and all those lights. And Tommy had it, taped from ITV when Spielberg’s original version was first shown in the evening of 28 December 1981. I don’t recall if he started the film at the beginning, and I was more enthralled by the lights of the VCR rather than those filling out Ralph McQuarrie’s on-screen mothership. But as far as losing my video tape cherry goes – having my first VHS encounter of a movie kind with Close Encounters of the Third Kind was no bad thing.

‘I am a lineman for the county,’ sings Glen Campbell in his 1968 hit, ‘Wichita Lineman’, ‘and I drive the main road searchin’ in the sun for another overload.’ Searching in the sun and watching skies is the very essence of Steven Spielberg’s 1977 opus, Close Encounters of the Third Kind. And none more so than for its central character, county lineman Roy Neary, played with blue-eyed, blue-collar brilliance by Richard Dreyfuss. If 1982’s E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial is about a childhood stood facing adulthood, Close Encounters is about an adulthood contemplating childhood, as everyman Roy is soon both infatuated, consumed and enchanted by the orange-flavoured ‘ice cream’ lights bounding about the skies of Indiana. Close Encounters is about artists. It is about sculptors, painters, translators, musicians, communicators, photographers and science visionaries. It is a film that celebrates language in all its earthly, interstellar and visual forms. It is about holding a vision – whether it is Neary’s or Spielberg’s – and seeing it through to its natural and not always clear-cut conclusion.

Close Encounters is also vital to the sequence of Watching Skies movies. The very phrase ‘Watch the skies’ is of course an overheard piece of advice in the film, the name lent to the film’s publicity promo campaign and one of its initial working titles. Very much like its spiritual cousin E.T., Close Encounters initially unfurls like a suburban horror movie. A young boy’s house is plagued at night by an otherworldly force, sending his toy trucks into a creepy frenzy and the contents of a fridge spilling onto the floor to remind all UK audiences we still do not have refrigerators or milk cartons that big. A panicking mother later pushes through a dark, cricket-heavy forest looking for that son. A single ‘star’ follows a truck across the Indiana highways. A pristine squadron of Second World War torpedo bombers is found in the Mexican desert with unspoiled cockpit photos of the sweethearts back home. An old-timer whistles ‘She’ll be Coming Round the Mountain’ whilst ignoring the young boy stood perilously on the canary-yellow lines of a mountainous road. Other locals huddle with a kindred yet ever so sinister unity to evangelise the skies for reasons that so far evade both us and them. And as the whole of Indiana is left in a haunted state of high alert, very soon our hero Roy Neary is in the grips of an obsessive breakdown and marriage break-up.

To be the one who splits the family in a Spielberg film and to get away with it as chief protagonist is no mean feat. The families in a Spielberg movie are often already broken – with those responsible often cast off into the story wings. However, with his Falstaffian lunges of mud at his Devils Tower sculpture in the lounge mixed with that dogged independence of American Graffiti’s Curt and the unhinged spontaneity of Jaws’ Hooper, Dreyfuss has only to arc those baby blue eyes up at the skies and we buy it. Add a touch of beatnik, on-the-road scruffiness and a Rockwellian humility, and the lineman for the county becomes an intuitive sculptor-cum-interstellar ambassador with a face ‘like a 50/50 Bar’. Key to the film’s titular close encounter, Roy is of course a belligerent bull in the authorities’ china shop. But as the recent political memories of Watergate and Nixon dictate, no government official is to be trusted, despite the UN flags getting events off on a benevolent footing. The officialdom of the film is the scientists working above the law and the extra-terrestrials clearly trust Roy. It is his determination and final-act attendance which possibly validates the whole mission continuing on the aliens’ terms. He is both ambassador and chief witness, and it is one of Dreyfuss and Spielberg’s fundamental performances.

Jaws, Close Encounters and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial are Spielberg’s career-defining ‘everyman trilogy’ – a key sequence of movies vital to their cultural zeitgeist, key to Steven Spielberg and key to American cinema of the 1970s. Like Tom Hanks and Mark Rylance after him, the suggestion is that Richard Dreyfuss is of course an extension of director Spielberg himself. But in Close Encounters – which is the first and only time Spielberg gets sole screenwriting credit on a film he has directed – the director is also there in Bob Balaban’s cartographer-cum-translator Laughlin (‘are we the first?!’), the wide-eyed innocence and lack of judgment of Cary Guffey’s pre-schooler Barry Guiler (‘you can come and play now’) and undeniably Francois Truffaut’s Claude Lacombe (‘Major Walsh, it is an event sociologique’). That casting decision, to place a trailblazing film director of French new wave cinema at the mainstream end of an American new wave in a role that celebrates both Truffaut’s personal gravitas and his passion for cinema, is a delicious beat of Close Encounters. As Lacombe masterminds and supervises the Devils Tower landing project, he does so like an overexcited film director on set – commanding his sound levels, keeping the cameras rolling, positioning his lights and quietly allowing on-set visitors to stay and watch the skies unfold. For Truffaut, Neary may as well be Spielberg.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is dripping in a late-1970s Americana, and it was a heady mix to a British kid with milk bottles not cartons and fridges not refrigerators. We had torches. America had flashlights – with the longest beams dramatically cut through with that Spielberg cold breath and mist. We had Panda Pops. America had Dr Pepper. We had our dinner already on the plate. America had bowls of food in the centre of the table to help yourself. We had three TV channels. America had multiple TV channels, Looney Tunes for breakfast, a whole button of local news, The Ten Commandments playing on tap and remote controls. Add to that the mailboxes with their plastic semaphore flags, railroad crossings, bridge-playing grandmothers with their cat-eye spectacles, lone trucks ploughing across midnight freeways, khaki-clad generals on portable phone units, fly doors, the clapping cymbals of a Musical Jolly Chimp, mounds of mash potato and those canary-yellow road lines never that far away from the drama, and you have a fierce and lucid Spielberg sense of post-baby-boom America. It’s a textured blue-collar world – handing American cinema a working-class baton that continues in the likes of The Deer Hunter (1978), Blue Collar (1978), Norma Jean (1979), Alien (1979), Silkwood (1983), Mask (1985) and arguably The Terminator (1984). Unlike Jaws’ Chief Brody (Roy Scheider), who is on a police promotion with a decent Cape Cod home, amicable colleagues and a car ‘in the yard’, Roy Neary’s world is one of intolerant bosses, coupons, being at the mercy of middle management and getting fired. Yet this is still a 1970s Spielberg movie. Close Encounters still operates in the same domestic world as that of the Brody family in Jaws, with its Snoopy poster in the kids’ bedroom, Marvin the Martian on TV, a Star Trek USS Enterprise model hanging in the lounge, Ronnie Neary cutting out and hiding a local paper’s UFO news flanked by a report on the unexpected box office success of Star Wars (complete with parochial news typos and misspelt actors’ names) and the military hides its UFO-welcoming infrastructure in plain sight behind branded Baskin-Robbins, Coca-Cola and Piggly Wiggly trucks.

Spielberg’s films are often predicated on passions – whether it is those that look beyond the stars, into the woods, under the waves, along the benches of the Senate or newsrooms of DC, into the darkest recesses of European history or those that are simply about getting home. Notions of home are tantamount to many a Spielberg movie and many a Watching Skies-era movie. E.T., Superman, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Poltergeist, Gremlins and Star Wars are all pivoted on the home or a guiding sense of it. And when Barry Guiler impulsively opens that front door as his home is besieged by a terrifying display of domestic mayhem, juddering ovens, wild vacuum cleaners and an unsolicited Johnny Mathis on the record player reminding all mothers in Watching Skies movies to flee the house when they hear the tones of said knitted crooner (Frances Lee McCain clearly took no such note in 1984’s Gremlins), Vilmos Zsigmond’s orange horizon cutting across the trees is as instantly ingrained into the psyche of 1970s cinema and its sense of home as John Wayne opening that door to an altogether different American frontier in John Ford’s The Searchers (1956). Yet, the visual orchestrations of Close Encounters are not all fairy lights bombast and lens glare splendour. If one assumes it was Jaws and 1975 that properly ignited Steven Spielberg’s moviemaking credentials and the box office fortunes of a whole decade’s movie output, one is already overlooking how large-scale and finely orchestrated The Sugarland Express and Duel are too. Large-scale visuals in Close Encounters are not just the mother lode of the mothership, but the exodus chaos of panicking hoards pushing onto freight trains with their gas masks and all those future echoes of Schindler’s List, cars convoying out of sight along those canary-yellow lined roads, UN trucks bouncing over the dunes of the Gobi Desert and hundreds of villagers scampering to tell their story in Northern India. Spielberg is adroit at putting a national event on a local, personal scale. And vice versa. Sugarland is a prescient and true tale of a criminal action being lent a state-wide and snowballing celebrity. Close Encounters is telling a soon-to-be-global story from its initial, almost small-town beginnings. If anything, of Spielberg’s first three theatrical features – The Sugarland Express, Jaws and Close Encounters – the one about the shark is the smaller, more intimate picture.

Whilst it is a mix of time, life and the story subjects Spielberg settles upon in his movie timeline, as the 1980s continues and he no doubt settles down to raise Neary and Brody kids of his own, it is arguable that the women in his films shift away from that contemporary passion and zeal. After Whoopi Goldberg’s turn as Celi in The Color Purple (1985) and Holly Hunter’s Dorinda opposite Dreyfuss in Always (1989), Spielberg’s movies possibly surrender that 1977 suburban and domestic edge. Jurassic Park (1993) and The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997) are steered by modern science and corporate cynicism, but also pinned to a timeless Indiana Jones safari world where mothers and girlfriends are absent (unless one counts the mothering instincts of the T. rex in The Lost World).

After Jaws and its high seas machismo, here Spielberg’s own script pins protagonist Roy between two resilient women – both of whom end the film as single mums. Jillian Guiler (Melinda Dillon) and Ronnie Neary (Teri Garr) are immediately part of a rich line of key women in Spielberg movies, which by 1977 has already notched up Something Evil’s Marjorie (Sandy Dennis), The Sugarland Express’s Lou Jean (Goldie Hawn) and Jaws’ Ellen (Lorraine Gary). And they would soon be followed by Raiders of the Lost Ark’s Marion (Karen Allen), E.T.’s Mary (Dee Wallace) and Poltergeist’s Diane (JoBeth Williams), Tangina (Zelda Rubenstein) and Dr Lesh (Beatrice Straight). And despite being released forty years after Close Encounters, it is curious how one of Spielberg’s key female roles is now The Post’s Katharine Graham (Meryl Streep) in a story which not only examines the Pentagon Papers and less fictional government cover-ups of 1971 but also the gender politics of 1970s America from a prescient 2018 standpoint.

‘Don’t you think I’m taking this really well?’ remarks housewife and kids’-tantrum-wrangler Ronnie Neary as she strives to be enthused by husband Roy’s early morning fixations with watching skies. Whilst Ronnie ultimately refuses to share her husband’s journey down the UFO rabbit hole in favour of protecting her family, artist Jillian almost understands the extra-terrestrial long game at play as her son Barry is taken by the skies for a greater good. The manner in which a traumatised Jillian is hounded by men and reporters at a press conference scene – restored by Spielberg in the 1998 Director’s Cut – is wholly uncomfortable as she is thrown to the press wolves and the ever-so-jealous Ronnie chooses to sit quietly by and not defend a mother trapped in government headlights. One of the screenplay’s skills is that Roy’s burgeoning friendship with Jillian is barely a romance. They share more in common than not with the thumb-trippin’ pair in Spielberg’s student short, Amblin’ (1968), as the likeminded souls Roy and Jillian are flung together because the skies watched them too. Like Poltergeist’s Diane and E.T.’s Mary, there is a sense with the artist Jillian of a distant ex paying the bills and a late-1960s, possibly rebellious student life at Boston University – as seen on son Barry’s T-shirt. Whilst the broken home motif is often a pertinent one to Spielberg, that is not what Close Encounters is about. For a film that starts in a foreign language, has no discernible villain and sees all its kid characters taken away, the film is also not about the creation of a romance. It is too preoccupied with those 2001: A Space Odyssey cosmic conundrums encasing our place in the universal scheme of things. And cinema.

Melinda Dillon’s role was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress in a year that saw co-star Dreyfuss become the youngest actor at the time to nab the Best Actor Oscar for Neil Simon’s The Goodbye Girl (1977). He was barely 30 years old and even younger when he shot Jaws and Close Encounters. Without doubt Melinda Dillon, Teri Garr, Lorraine Gary and Goldie Hawn can all stand tall in a crucial decade of American movies where the bearded, long-haired and plaid-shirted director geeks from film school were now dictating the course of mainstream cinema – and often via female protagonists. Jane Fonda in Klute (Alan J. Pakula, 1971), Karen Black in Five Easy Pieces (Bob Rafelson, 1971), Ellen Burstyn in The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973) and Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (Martin Scorsese, 1974), Gena Rowlands in husband John Cassavetes’ A Woman Under The Influence (1974) and Gloria (1980), Louise Fletcher in One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest (Milos Forman, 1975), Talia Shire in Rocky (John G. Avildsen, 1976), Sissy Spacek in Carrie (Brian De Palma, 1976), Faye Dunaway in Network (Sidney Lumet, 1976), Diane Keaton in Annie Hall (Woody Allen, 1977) and Meryl Streep in The Deer Hunter (Michael Cimino, 1978) and Kramer Vs Kramer (Robert Benton, 1979) – these are all vital notches in the timeline of 1970s cinema, and all with a contemporary zeal heavily predicated on women.

When watching these movie skies and asked to believe that these shark infested galaxies far, far away can fly, we are also repeatedly watching the labours of women – the crucial ladies both behind and alongside the cameras of this American new wave. Often tutors, classmates and creative allies from the film schools and movie circles frequented by the likes of Spielberg, George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, Peter Bogdanovich, Lawrence Kasdan, Walter Murch and Martin Scorsese, these movies of the Star Wars generation – like the Bond series – never operated in a male vacuum. Universal Pictures’ Vice-President Verna Fields edited The Sugarland Express and Jaws