11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

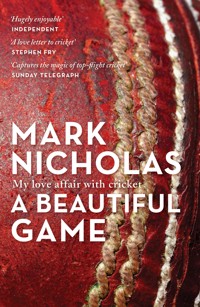

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

WINNER OF THE CRICKET BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD AT THE CROSS BRITISH SPORTS BOOK AWARDS 2017 WINNER OF THE MCC/CRICKET SOCIETY'S BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD 2017 Mark Nicholas, the face of Channel 5's Cricket on Five and anchor for Channel 9's Test commentary team in Australia, has a unique knowledge and perspective on the world of cricket. As both a former player and now a professional observer and commentator on the game, he knows all the key figures of the sport and has witnessed first-hand some of cricket's greatest moments. His book is a personal account of the game as he's seen and experienced it across the globe. From epic test matches and titans of the game like Lara, Warne and Tendulkar, to his own childhood love for the sport, Mark gives us his informed, personal and fascinating views on cricket - the world's other beautiful game.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

First published in 2016

Copyright © Mark Nicholas 2016

The moral right of Mark Nicholas to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

‘If I Should Go’ by Joyce Grenfell © The Joyce Grenfell Memorial Trust 1980. Reproduced by permission of Sheil Land Associates Ltd.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Allen & Unwin

c/o Atlantic Books

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Phone: 020 7269 1610

Fax: 020 7430 0916

Email:[email protected]

Web:www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN 9781760291983

Trade paperback ISBN 9781760292751

E-Book ISBN 9781952535314

Set by POST Pre-Press Group, Australia

Cover design: Deborah Parry

Cover photographs: Nicholas Wilson (author photo); Ryan Pierse–CA/Cricket Australia/Getty Images (Adelaide Oval)

To Mum and Dad for making it all possible

And to Kirsten and Leila for continuing to make it all so worthwhile

CONTENTS

PART 1: PLAYING THE GAME

1 In the beginning

2 Hampshire, 1977

3 Australia

4 The Hampshire captaincy

5 The Smiths

PART 2: THINKING ABOUT THE GAME

6 The art of batting

7 The week we wished that wasn’t and the spirit of cricket

8 Fast bowling

9 When spin meets glove

PART 3: TALKING AND WRITING ABOUT THE GAME

10 Media days

11 Australia again, and a call from Kerry

12 2005 and all that

13 A crystal ball

Epilogue: A beautiful game

Love is lost

Postscript

PART 1

Playing the game

At home, aged twelve, in the garden where the Test matches were played. (The door on the right was the entrance to the pavilion!)

CHAPTER 1

In the beginning

The Nicholas family moved house in the spring of 1967. We left a small terrace in Holland Park for the leafy fringes of Roehampton, barely more than a six-hit from the gates to Richmond Park. The new home had a wonderful garden with a lawn and flowerbeds big enough for my mother’s interests to sit comfortably alongside mine.

My father and I mowed a narrow strip of grass just beyond the brow of a small tier that hid the white lines we had painted with emulsion as batting and bowling creases. Then I rolled the strip with the barrel of the lawnmower until it appeared flat enough for play. I was nine years old and the game of bat and ball had stolen my heart. The move from street cricket, with stumps chalked on the brick wall outside our old home, to something like the real thing on grass, with a pitch and boundaries, had cast a spell.

My father, Peter, was a decent, if cavalier, club cricketer in the Richie Benaud mould. He struck the ball well and tossed up leg breaks with a splendid lack of concern for their outcome. His interest in cricket came from his own father, who was a wicketkeeper-batsman for the army and Essex and a fine all-round sportsman. With some surprise, I recently found Captain F.W.H. Nicholas, or Freddie Willie Herbie as the lads knew him, in the front row of a huge team photograph in the Lord’s museum. Apparently my grandfather was much sought after by philanthropists who took the game far and wide. He was a great mate of the Honourable Lionel Tennyson, who captained Hampshire from 1919 to 1932, and of the entrepreneur Sir Julien Cahn. The picture in the museum is of Sir Julien’s XI in Jamaica and I have no idea what it is doing there.

I went with Dad to as many of his games as he would allow, never missing a ball when he was in action and otherwise eagerly playing around the fringes of the boundary with anyone who would have me. He played league cricket for Southgate and wandering cricket for the Free Foresters and the Frogs. Nowhere in the world enjoys wandering cricket like England. It is a throwback to an amateur age of free time and great privilege, and exists to this day. At the top of the tree, clubs such as the I Zingari and the Arabs tell us as much about ourselves as the games we play.

When my father came home from work, he would play in the garden with me each evening. I loved this more than I can describe here. He gave me a coaching book by Sir Donald Bradman, The Art of Cricket, and an autobiography by Denis Compton. I was submerged in a world of images, characters, sensations and ideals that were to accompany me throughout my life.

In the late summer of 1968 he took me to Lord’s. We sat in the Warner Stand with friends. When Ted Dexter came out to bat for Sussex against Warwickshire in the Gillette Cup Final, I lost the plot, cheering wildly and generally making a goose of myself. Dexter didn’t score many but he could do no wrong in my eyes. We had a marvellous day, although Sussex lost. We travelled home together and hurried to the garden, where there was enough light to re-enact the most memorable scenes from the match: a Dexter boundary, John Snow cruising to the wicket and so on. Our shared love of cricket—and music, incidentally, for he was a fine pianist—was an unbreakable bond.

Nine days later my father died. He was 41.

He had moved from Southgate Cricket Club to Wimbledon Cricket Club with a view to playing a little less and more locally. On the Sunday afternoon after the Gillette Cup Final a fellow team member brought him home early from a match. His face was ashen and he went to bed. The immediate diagnosis was that he had picked up a stomach bug from my two-year-old brother, Ben. On Monday, he seemed a little better. That Monday night—or at 2 am on Tuesday, to be precise—he died in bed alongside my mother. Unsurprisingly, the night lives with her to this day.

I was a few weeks short of my eleventh birthday. My sister, Susanna, was twenty months younger. We had no idea why we were whisked off, first thing, to family friends for much of the day.

We returned home around teatime and Mum was waiting for us in the hall. She took us into the sitting room and explained that Dad had died. We were later to hear that a congenital heart condition had betrayed him, and us. These days he would comfortably have survived.

A deep aching sadness overtook our home. It was as if it rained all day and all night. I talked to him in my bed, imagining he would hear, but the deafening silence overcame us all. We slept together in my sister’s bedroom for comfort, though little could be found. Our family was always as one and blessed by love, laughter and warmth. Now, the void exposed us as mortal and highly fragile. Honestly, how does a mother cope? We were beyond pain.

Three weeks into the autumn term, my mother took me back to Fernden, the boarding prep school I had started the year before. Neither she, nor my father, had any idea how much I hated it. The saving grace was a headmaster with kindness at his core and cricket set almost as deep in his heart as in mine.

Charles Brownrigg ran an old-fashioned school—not quite Tom Brown’s alma mater though along similar lines—but such emotionless authority over young boys did not come naturally to him. Age had taken its toll and so his wife, the matrons and the other masters made the place tick. Mr Charles’s true colours were to be found in the summer term, when cricket was played at every opportunity: in the schoolyard during midmorning break; again for half an hour before lunch; throughout the afternoon in organised and disciplined form; and then, for those of us with greater interest or skill, private coaching sessions with him each evening after tea. This was wall-to-wall cricket for three to four hours each day, with matches against other schools twice a week and house matches that were ongoing throughout the summer term. It was heaven.

In the spring and summer holidays at home, I rolled the pitch with even greater vigour and invited friends to play out Test matches. Play began at 11.30 am, lunch was at 1.30 pm and tea at ten past four. Mum never let me down. Even the sausages and mash had to wait until 6.30 when we finished. Invariably, I/England would declare with around 500 on the board and knock over my mate/Australia or West Indies for next to nothing and win by an innings. Friends went by the wayside almost weekly.

I could mimic Geoffrey Boycott’s exaggerated defensive positions, Colin Cowdrey’s easy manner, Tom Graveney’s unusual grip and Ted Dexter’s magnificent poise. I copied John Snow’s beautiful rhythm and Ken Higgs’s angled approach, with his bum stuck out and his snarling response ready for every opponent. I worked right-arm on Derek Underwood’s left-arm deliveries and mastered the arm ball with which Fred Titmus trapped Garry Sobers—at least, I thought I did.

The score was recorded each over. At the fall of every wicket, the dismissed batsman had to walk across the garden, into the house, up the stairs and into the small bathroom, where he removed his gloves, put on a different pair and set off back to the middle. Always, the new batsman was applauded to the crease. I think this was more for the sense of theatre than etiquette.

The only times during the summer holidays that these matches were put on hold was during a real Test match, when I sat glued to the television—black and white until the early 1970s—and watched every ball of every game. When we travelled, the car radio crackled with the magic. I could imitate Benaud, John Arlott and Brian Johnston, and did so for anyone who would listen.

At school, I smuggled in a small wireless and hid it under my pillow. During the winter nights of 1970–71, I listened in awe as Boycott and Snow helped Ray Illingworth bring the Ashes back to England. That crackling sound, Alan McGilvray’s distant voice, and the news that Snow had nailed Ian Chappell, opened this young mind to a cinematic vision of Australia.

There was an added edge to the second of the two Tests at the Sydney Cricket Ground, when Snow was collared by spectators after his bouncer hit Terry Jenner in the head and Ray Illingworth led his players from the field in a protest for their safety. For me, the SCG assumed almost mythical proportions, and those who played upon it became gladiators in the imagination of a young boy captivated by his heroes. As he ran down the battery and drifted into sleep, his heart beat with the rhythm of the great southern land and from the roar of the crowd whose hard-nosed opinions on the action out in the middle was the stuff of the Colosseum.

I was pleased to move on from prep school. The place represented a deeply troubled time. My nights were filled first with tears and then a challenging nightmare in which I ran downhill from a huge boulder that chased me until the very moment it was to flatten me. I awoke in panic night after night. There was some bullying, of course, as is the way of young boys, and some unsympathetic schoolmastering from men completely unable to deal with such complex emotional trauma.

Cricket was the release. Cricket, cricket and more cricket. I devoured the game in newspapers, magazines, radio and television. I collected those cigarette cards, read the Playfair Cricket Annual and even dipped into The Cricketer and Wisden. Though football and rugby were key components of winter life, cricket still found a place when England toured abroad.

In the spring of 1970, I asked Mum for a new bat. That tested her. She worked her way through the drawers of Dad’s desk and found a receipt for cricket kit from a shop in Soho. Soho! She asked me what I knew of Alfred Jameson Sports, a question that confounded me as much as her. She called the number and a man answered who introduced himself as the Mr Jameson. He said he had the summer’s new range of equipment in stock. And so off we went: me with uncontrollable excitement and Mum with some trepidation. The Soho of 46 years ago was no place for a lady.

We arrived in Greek Street and parked our green Morris Minor outside an old-curiosity-type shop. We descended a small flight of steps and rang a bell. An ageing man with a white moustache greeted us. Peter Nicholas had been a customer for a while now, he said, through a mutual friend at Southgate Cricket Club. Phew. Mum explained that Peter had died. Mr Jameson seemed genuinely sad and promised us the same discount afforded to my father.

I touched the bats, feeling the smooth, cold wood in my fingers. I studied the grains, the bows and the handles. I pulled on gloves, opening and closing my hands inside the soft, fitted leather. I touched pads of all sizes, and admired photographs of Bradman, Hutton, Edrich and Compton.

Mr Jameson pulled out a Gray-Nicolls and began tapping the ball on its face. Then he bounced it, increasingly higher until the odd one hit the ceiling: goodness, he said, what a beautiful piece of willow! This was a long-practised sales pitch and Mum was falling for it. I had other ideas. I picked out a bat with a new logo—a thick black triangle—that I had seen used by Basil D’Oliveira. Mr Jameson disapproved. He said it was heavy and that at my age I needed a lighter bat for greater flexibility. I persevered. On closer inspection the triangle was an image of three stumps and two bails. The bat was called a Duncan Fearnley.

It was an argument I was never going to lose. At the age of thirteen I had my first Fearnley. Better still, Mum decided Dad’s visits to Soho had been virtuous. We went back each spring and then, one year, this old curiosity of a sport’s shop had gone, replaced by a Chinese restaurant. Alfred Jameson had played his last innings. Hopefully, he was with Peter Nicholas, both bemoaning the fact that the Nicholas son and heir was out in the middle with a bat that weighed more than it should.

Six months later I started at Bradfield College in Berkshire. Initially, the days there were no better than at Fernden prep school but after a year a new housemaster took over and brightened up ‘G House’. Chris Saunders had won cricket and football blues at Cambridge and Oxford respectively and quickly understood the individual needs of boys in their early teens, who were often frightened and certainly alone.

Chris had a real gift. He hammered the bad ’uns and stoked the good ’uns. He mixed leaders with losers and let them teach each other about both sides of the coin. He allowed Johnny Muir—addicted to nicotine by his mid-teens—to smoke in his own house rather than find him out at the bike sheds corrupting others with Embassy Regal or Player’s No. 6. He encouraged a lad whose parents lived in Borneo to make the long journey home worthwhile by coming back late after the Christmas holidays. Best of all as far as I was concerned, he encouraged everyone to play sport whatever their limitations.

With a firm but always fair and light-hearted touch, he lifted the general malaise that had overtaken Bradfield—as it had so many of Britain’s schools during the early 1970s. Drugs, cigarettes and alcohol were more appealing to many teenagers than Dexter, George Best and David Duckham. Some grew their hair long and then, having rolled it into a bun, held it in place above their collar with pins and clips. When Mike Wright was badly tackled in a 1st XI football match, he hit the frozen ground with enough momentum to somersault forward and into the sideline crowd of masters and schoolboys. Out flew the pins and clips and, to Mike’s acute embarrassment, so too the bedraggled locks that hung halfway down his back. As soon as the match was over, our new housemaster frogmarched Mike to the school barber, where the hair was hacked off above the collar and looked ridiculous for the remainder of the term.

In many ways I was lucky at Bradfield. Chris was a brave and enthusiastic wicketkeeper, who knew the game. The head of cricket, Dickie Brooks—another wicketkeeper—had played for Somerset. As one coach, Maurice Hill—formerly of Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Somerset—left for other pastures, John Harvey, the recently retired Derbyshire batsman, arrived in his place. I was picked in the 1st XI when I was fifteen and played in the team for four years, the last as captain. I never made enough runs but took wickets with decent outswingers at medium-fast. These three good men guided me on the path to my dream. I was way ahead of anyone as a captain and led an unbeaten team in my final year. Chris appointed me head of house and encouraged me to take charge of everything within my reach.

The runs thing was odd. In my last year at prep school I made four hundreds, a remarkable tally for a thirteen-year-old. Possibly I pressed too hard at Bradfield. Maybe I was promoted too early for my fragile mental state and this had the reverse effect of holding back my performance as I played constant catch-up. Maybe I was too cocky and cricket was already teaching me about myself.

I joined the Bank of England Cricket Club—Mum knew someone, or Dad had, and the ground was next door to home—and played for them in the Surrey League during my mid-teenage summer holidays. The earthiness of the cricket was appealing, more so than the nature of wandering cricket, which was formed around the old-boy network of the British public schools. Some of these clubs—Butterflies, Free Foresters and Stragglers of Asia among them—played against Bradfield during the school term, and my desire to beat them was every bit as great as my desire to beat other schools. With the benefit of hindsight, I now think that I had already latched on to the problem cricket faced with elitism. Bradfield boys had this magnificent ground—still one of my five favourite in England—and the chance to enjoy cricket as a way of life. Youngsters I knew around London had no such luck. There was a smugness about many of the men from the clubs who came to play us. This was not necessarily a conscious thing. It was inherent. The shame to me was that the institution of cricket would not spread its wings.

Once, in a moment of jaw-dropping condescension, an opposing captain won the toss and asked what I wanted to do first. I thought sod him and set out to win the match at any cost. I replied that we would bowl first, to which he warmly agreed. I used our two best bowlers for most of the innings, operating to defensive fields with plenty of cover on the boundaries. We fielded feverishly, denying runs as if our lives depended upon it. By the midpoint of the match, the opposition were not more than 140 for 3 or 4.

These were declaration matches, not limited overs and, on a flat pitch, 140 was nowhere near enough. But no club side of grown men could be seen to bat too long against schoolboys. The captain arrived at the wicket looking to push the score along but perished caught on the square-leg fence. He left red-faced. Another half an hour or so passed as increasingly exasperated gentlemen came to the crease, only to lose their wicket attempting to catch the clock. Eventually, about 40 minutes before tea, they declared 9 wickets down. We needed about 200 to win. I changed the order round, sending in a couple of hard hitters against the new ball and keeping the opening batsmen for later should the match need saving. It didn’t. We got off to a flyer. So much so that after tea we were able to pace ourselves. I got to the wicket with about 90 needed from the obligatory twenty overs in the last hour. We cruised home with time to spare and celebrated long and hard.

In the summer holidays of 1975, I was asked to play for Middlesex Under-19s. I turned up at the Barclays Bank ground in Ealing to find I was playing in a team with Mike Gatting, who was one of the three stand-out young batsmen in England, along with David Gower and the less well-known Matthew Fosh. Though a year younger than Gatt, I hoped to have the chance to compare myself with him but I didn’t get in to bat. We won by 9 wickets. Gatt, who finished unbeaten with 70-odd, was in a different class, a completely different class. Within a couple of years, he was with England in Pakistan. I played a few more games the next summer but lovely old Jack Robertson—briefly an England batsman after the war—who ran the side, thought more of a couple of other lads who had grown up within his radar. Soon enough, I had moved on anyway.

My mother had empowered me to fully embrace cricket. Thus, when the sun shone, I rejoiced. On those summer mornings when it rained, I pined. From the age of fifteen to eighteen, I turned down family holidays on the Isle of Wight, in the New Forest, to France and to Corfu so that I could catch bus and train, cricket bag in hand, to turn up everywhere and anywhere for a game.

Dad may have gone but his memory lived on through this shared passion for cricket. A beautiful game was the friend to whom I had turned in September 1968 and the friend who remains firmly by my side to this day.

CHAPTER 2

Hampshire, 1977

There were Jim the Fizz, Pops, Pokers and PT; Hillers, Murt, Elvis and Pissy Pete; Lew the Shag, Jungle Rock, Herbie, Trooper, Dougal and Dicey Rice. Most of us, and a few more, were based in a small room in the bowels of a pavilion building so dilapidated it was noteworthy that the council passed it fit for business. Assuming it did.

Hampshire County Cricket Club was run by Desmond Eagar and had been since the 1950s. His second-in-command was the club captain, Richard Gilliat. My first year—as a wet-behind-the-ears triallist set on a life in cricket—was 1977, Desmond’s last. We freshers saw little of Eagar and not much more of Gilliat but there was no mistaking that they were in charge.

We were the County 2nd XI, the Brat Pack, uncapped staff players who bowled in the nets in pretty much all weather. We ran the scoreboard at 1st XI home matches and helped the ground staff with the covers and such. We took turns to act as 12th man for the gods who lived in the little cottage upstairs: the capped 1st XI players. This was a mystical chamber into which we were rarely allowed. Entry to the first-team dressing room came via knocking and then permission, even as 12th man. This was a coveted role, simply to rub shoulders with some of the best players around—Barry Richards and Gordon Greenidge, for example, Andy Roberts, Trevor Jesty and Gilliat himself. But after a few days at it, you understood that the public-school fagging system was far from dead.

First up, before play, you served the lads tea, coffee and a couple of digestive biscuits. At lunch you turned waiter for the bowlers or unbeaten batsmen—ham rolls usually, or the tasteless fare from the dining room, plus lashings of Heinz salad cream. At tea, you ran for cover if things were going badly out on the field but not before ensuring the sandwiches had been delivered by the kitchen and the teabags had drawn. If Hampshire was in the field, you made your way to the scorer’s hut to collect the bowling figures and deliver them to the captain. Weirdly, he tended to look in the maidens column first, as if maiden overs were the route to a pot of gold. Yes, wickets were okay, ‘but maidens, lad, maidens: give ’em fuck all’.

Towards the close of play you filled the huge communal bath into which the naked gods descended as one, having supplied their order for drinks—beer, lager, Coke, orange juice or milk, mainly—and ran various other errands. That bath was an unhealthy thing all right, unless you got there first and were gone before the bowlers’ feet began their long and weary soak.

I was first taken upstairs to this holy place by Mike Hill (Hillers), the 2nd XI wicketkeeper, when the first team were playing away from home and we were doing six-hour days in the nets. He showed me an enormously heavy bat, made from dark wood, that he said Barry Richards used in Sunday League games. He claimed it weighed 4 pounds, which I had no reason to doubt. It was enough for me to just to hold a bat used by Richards, the cricketer who could do no wrong in my eyes. Swooning, I made to drive, cut and pull, shadowing the great man’s stance and technique, with an exaggerated position of the left elbow and a flourish in the follow-though. But the bat weighed me down. The strokes seemed near impossible. This was a club, not a bat. What was I to believe? That Richards was immortally strong? That the journey I so badly wanted as the bookmark to my life was already beyond me because I could not lift the great warrior’s sword?

Hill had now been joined by Nigel Cowley (Dougal, after the dog in The Magic Roundabout) and Tim Tremlett (Trooper, for his military gait and Roman nose). They began to laugh among themselves. This was no bat used in matches by Richards but a demo, made from oak, which he used to warm up immediately before going out to bat. It made his actual bat feel like a wand, allowing his muscles to adapt quickly to the challenge of the new ball. I disappeared to the bowels below, tail between my legs and their laughter in my ears.

Hampshire was an old-school club: institutionalised in that shabby English way, financially poor but mainly happy. The place chugged along, just about breaking even in an age when no one talked about money, only manners. Eagar was as much headmaster as former captain and secretary. Much loved and respected, he was to die suddenly late that September, aged 59.

Once, he offered the young leg-spinner Alan Castell a drink in celebration of his first five-wicket haul. ‘I’ll have a pint of bitter, please, Mr Eagar,’ said Cass. ‘Castell, a word in your ear,’ Eagar replied. ‘When a senior member of the club offers you a drink, ask for a half, Castell, a half. Now then, Castell, let me buy you a drink to celebrate your bowling today.’ ‘Thank you, Mr Secretary,’ said Cass, ‘I’ll have two halves of bitter, please . . .’

Occasionally, something—or someone—arrived to break the ever-so-slightly-grey rhythm of life. To a degree, Castell was one of those but his cricket never kicked on and soon enough he too was one of the game’s lost souls. Long before my time was the first and very best of them, Colin Ingleby-Mackenzie, the Old Etonian who led the county to the championship in 1961 with outrageous flair and abandon. The stories of that summer have become the stuff of legend. Wild optimism; dashing parties in London decorated by beautiful ‘It’ girls; wads of cash laid down, won and lost track-side at Ascot; crazy declarations on the cricket field and miraculous victories from nowhere all came together to beat Yorkshire—far and away the best team in the land—to the championship title. When not gallivanting around London, Colin lodged at the Eagar family home in Southampton, frequently getting in as Desmond was getting up.

Hampshire’s approach was well summed up by Ingleby’s response to the interviewer’s first question at the BBC Sports Personality of the Year night in London. ‘Well, Colin, this was quite a performance by your chaps. What was the secret?’ asked Peter Dymock. ‘Oh, I don’t know really. A bit of luck, I suppose,’ replied Colin, ‘and a simple enough rule that I wanted the chaps in bed by half past ten, to be sure that they got an hour’s sleep before the start of play.’ Boom, boom. ‘Gosh,’ or some such thing, said Dymock. ‘So it’s true, Colin, that you did it with wine, women and song?’ ‘Well, I don’t remember much singing, Peter,’ replied Ingleby, before howling with laughter.

It was a long time before I came to know Colin personally but when I did there was no going back. He was the best of men—joyous, charming, generous of heart, spirit and pocket, and very funny. My greatest privilege was to be asked to speak at his memorial service at St Paul’s Cathedral, an occasion attended by almost two thousand people whose lives he had touched.

Afterwards, the family gave a reception at the Merchant Taylor’s Livery Hall in the City. I was talking to Colin’s wife, Storms (née Susan Stormont-Darling), when a hard slap at my right shoulder caught us all by surprise. I spun round and there, tall and elegant and wearing a black velvet Fedora with a cream silk scarf draped around his shoulders, was Peter O’Toole. Can you imagine! ‘Bloody good, dear boy, bloody good. I did Lean there. It’s a fucking awful place!’ And then he smiled, the most majestic smile in all the world, and disappeared from view. I never saw him again.

The last time I had seen him was on stage as the lead in Keith Waterhouse’s mischievous play Jeffrey Bernard is Unwell, a role to which he was ideally suited. Years earlier, in the winter of 1979–80, we shared the same net in the indoor school at Lord’s. He was a mate of the coach and former England left-arm spinner, Don Wilson, and liked to hang out with the young wannabes of the professional game. On occasion, he would buy us Chinese dinner up the road after the nets were done. He was just about the most alluring man I have met. How anybody avoided falling in love with him, I do not know.

‘Lean’ was David Lean, who directed Lawrence of Arabia, and O’Toole was right about St Paul’s from a speaker’s point of view. Because you perform from the other side of the dome from the audience, you feel isolated and the sound of your voice feeds back at you—‘It’s a fucking awful place.’ Having said that, it is beautiful place too, and as I began to talk about Colin, the sun came out, flooding the circle beneath the dome with a golden morning light. It was as if his spirit had dropped in to reassure us that all was well upstairs and though today was very nice, we should dry up the tears and crack on without him from here on in. Truly, we could feel this spirit, and who was to argue with the most optimistic man any of us had known?

After Ingleby, the white Barbadian Roy Marshall became the club captain. Marshall could really bat, the first of three truly great cutters of the ball that came from overseas to thrill Hampshire fans: Marshall; then Gordon Greenidge, also from Barbados; and finally Robin Smith, from Durban. But Marshall was a dreary captain or, if that is unfair, he was not a patch on Ingleby, who was the hardest act to follow. These were fallow years.

The club trod water until the arrival of Richards in 1968. After Ingleby-Mackenzie, Richards was probably Eagar’s best signing, though it brought controversy because the South African was on a higher percentage of ‘talent money’ than the other players. (Effectively, talent money was a performance-based bonus. Salaries were negligible but talent money could make a summer’s work properly worthwhile.)

Richards announced he would make 2000 runs in his first season and was scoffed at by the embittered old pros who played alongside him, especially when he failed on a green pitch in his first match. Though no one knew it then, Richards was among the finest batsmen on the planet. He made 2000 runs all right, and earned more talent money than the rest of them put together. Jealousy bounced all around the dressing-room walls. I was soon to discover that jealousy bounced all around the professional game.

That first year, I lived with Nigel Popplewell—Pops—in a flat halfway up Bassett Avenue, the main drag heading north out of Southampton. We lived off cornflakes, and roast chickens that were half-eaten one night, left to fester for the best part of 24 hours in the bowels of the oven in which they had been cooked, and then finished off the next day. Pops had a red Mini that took us to and from matches and to the pub. Rather too often, it brought us back from the pub, too. If there was no chicken in the oven, it was a pie and chips from the joint around the corner that the health inspector eventually closed down.

Pops’s father, Oliver, was a barrister before he became a judge—he chaired the inquiry into the Bradford City stadium fire—and was later knighted. He and my father completed national service in the navy together, which is how we all knew each other. One morning, we rolled out of bed for a game against the Middlesex 2nd XI in Winchester, gave the cornflakes a miss because the milk was rancid and hurried out to the avenue to find the Mini had been nicked. This was a blessing in disguise. Upon our hasty return to the flat to call both the coach, Peter Sainsbury, to tell him we would be late—not funny—and the police to report the theft—quite funny—we found the bathroom flooded and the floorboards giving way—very funny. The landlady, who lived in the flat underneath us, was banging at our door.

Pops, or maybe me (who cared, except her?) had run a bath and forgotten about it. By the time the cops turned up, the landlady had lost the plot. Our bathwater was a steady flow into her living room. The cops found the car two days later, abandoned in a derelict part of town. The landlady charged us proper money for the fix-up. We were on £21.50 a week so, with a few caveats, Judge Popplewell and Mrs Nicholas agreed to pick up the tab.

Stressed, we arrived by taxi at the St Cross ground in Winchester just before the lunch interval. The coach lost the plot too. He said it was our last chance, which seemed a little extreme, but it wasn’t the moment to point out that we had not been alerted to a first chance. The fact was, we were two public schoolboys, and the reasonable perception was that we had lived a life fed by the silver spoon.

Actually, Sainsbury—or Sains (what imagination we had for nicknames!)—was a fabulous man. He had played for the county from 1954 to 1976 as an accurate left-arm spinner, brilliant close fielder and gutsy middle-order batsman. Then, in a jobs-for-the-boys appointment, he became coach. He had no qualification other than a long and worthy playing career but county second elevens were run by former professionals who simply passed on their stock in trade. Frankly, Sains was not very good at it but he was a top bloke and we all adored him.

Popplewell didn’t make the end-of-term cut, sadly, but Somerset snapped him up, so somebody else lived off dried old chicken and stale cornflakes too. I was offered a two-year contract, starting 1 April 1978.

These contract announcements were made early each September and filled most of the playing staff with dread. Young players dreamt of glory in the game they loved. Fellows in their mid- to late twenties needed the job. Those in their early 30s, many of whom had long fallen out of love—with the game and often their wives, too—prayed for the chance of a benefit year and a tax-free windfall in recognition of their long service.

That autumn of 1976 had spelt the end for two splendid characters, Richard Lewis (Lew the Shag—though Lew went on to marry the daughter of the chairman of the club’s cricket committee and to become cricket coach at Charterhouse School, so not bad) and Pete Barrett (Pissy Pete, who loved a drink). Famously, when hit in the nuts by Michael Holding in Hampshire’s match against West Indies the previous summer, Pete lay writhing on the ground and looked up to see Clive Lloyd asking if everything was intact. ‘Think so, captain, but ’ere,’ said Pete, ‘would you mind asking yer fast bowler t’slow down a bit?’ Both were playing Minor Counties cricket in 1977 but hung around with us the rest of the time. Pete was a ripper bloke who tragically died in a motorcycle accident a year or two later. It took us a while to smile again.

Hillers and Andy Murtagh (Murt) stayed on to become 2nd XI senior pros, an oxymoron if ever there was one. John Rice (Dicey Ricey) was playing more first-team cricket, which was better than living on the fringe, so he got a two-year deal too. Same for Nigel Cowley. Rice played another five years and Cowley twelve. Both were destined to leave Hampshire unhappily—there is no easy way to release a professional sportsman—though they, thankfully, found fulfilment in the game elsewhere. Rice got the bullet in 1982 but was soon appointed coach at Eton College, a job he held for 30 years. His wife, Sue, ran the school shop, and together they became a popular and integral part of Eton life. Cowley played in our team that won the Benson & Hedges (one-day) Cup in 1988 before a brief spell at Glamorgan led to the end of his playing career. He turned his mind and spinning-finger to umpiring, and is still at it now. Increasingly, cricket takes care of its own.

The County Ground in Northlands Road, Southampton, was a quaint place. The pitch was good and the boundaries were shortish. I had first been there on a school trip to watch the 1975 Australians. Richards made runs in both innings, though Australia won the match with a convincing run chase in which Ian Chappell made a hundred. Absorbed and starstruck, I resolved to return one day and bloody well play out there myself.

Now here I was, on a month’s trial for which I was paid expenses but would have come for nothing. I was beyond nervous on arrival at those Northlands Road gates. Most of the guys had come through the Hampshire youth system but, having grown up in London, I played for Middlesex Young Cricketers where one or two others were ahead of me in the pecking order of Under-19s county cricket. The trial at Hampshire was courtesy of Gilliat, who had been contacted by my housemaster at Bradfield, Chris Saunders, who knew Gilliat from Oxford University playing days. Sainsbury then called the school coach, John Harvey, once of Derbyshire, and heard Saunders’ view endorsed.

I was shown to a small, cold, unglamorous changing room with pale-blue walls and a stark concrete floor in the basement of the pavilion, and told to change then report to the nets pronto. The first team were practising and I was sent to bowl in net 3. I looked up to see Richards on strike. Jeeesus. I ran in and bowled a gentle long hop, which, with a distracted air, the great man smashed off the back foot over my head. I ran to get the ball from the fence some 70 yards away. On return, I peeled off the long-sleeved Bradfield College jumper and tried again. Same ball, same result. Shit.

Nine months earlier, I had opened the bowling for the Public Schools XI against the English Schools Cricket Association (ESCA). That event had nothing to do with bowling at Barry Richards. I tried again, this time fuller and quite straight. Richards blocked it. At this stage of my life, it was the single most exciting thing I had ever done: bowled a ball that one of the two or three best batsmen in the world had blocked. I walked back to my mark, turned to face my hero and take him on again, only to see him walking into the next-door net. Please no. But yes, Richards had gone. That was it. Three balls in paradise. Over.

We bowled for a couple of hours in damp and chilly conditions before breaking for lunch, which, to my surprise, was at the pub down the road. I had chicken pie and chips. One or two of the lads introduced themselves properly. Tim Tremlett (Trooper) was kind and asked some questions about where I had come from and what cricket I had played previously. I think we drank pints of lager and lime or blackcurrant and lemonade. There were a lot of in-jokes to which I was not privy but I learnt that the 1st XI were done for the day and off to an away match at Lord’s. There was a whisper we would all have a bat later. Not so. I just kept bowling. Fun but not great for my lower back, which was iffy at best. Jim Ratchford (Jim the Fizz—physio, though not really, more a masseur with a good line in sweet talk) noticed me clutching the area of the sacroiliac joint. He offered Deep Heat and a rub. Christ, I thought, I can’t be seen on the physio’s bench on day one. ‘No thanks, Jim,’ which others told me was a wise move. Fancy that, some of the best players in the world and no qualified medical man in sight. Just Jim, who barely knew a calf muscle from a fetlock but gave a damn good rub when the aching soldiers presented themselves. Them were the days.

I stayed in a bed and breakfast next to the pub, slept well after the day’s excitement and woke to find rain chucking it down. My worst nightmare. I wanted to play cricket every day—yes, that’s every damn day. In general, old pros loved the rain and young pros hated it.

Thankfully, it relented by midmorning and we were back in those nets. I bowled better but was outplayed by David Rock (Jungle Rock, after the song), a young talent out of Portsmouth just a few months older than me. He had an easy upright stance and drove the ball through mid-on with authority. A few weeks later he was playing for the 1st XI at Portsmouth against Essex.

I had a chat with him at lunch—more pie and chips, pint of lager and lime, I kid you not—about his bat, which had a black triangular motif over the splice. Rock had used Fearnley equipment from the start of his career and explained that Duncan Fearnley was a former Yorkshire and Worcestershire batsman who now made his own bats at a factory in Worcester. This was a revelation to me. I had no idea there actually was a man called Duncan Fearnley. A year later, Rock took me to the factory to meet him. Duncan made me a bat, for goodness’ sake, and gave it to me, along with pads and gloves—all free. Mum liked that. (From that point on, every spring, I would spend a day with Duncan at the factory in Worcester. We got along famously and after mornings at the work-bench would break for long and alcoholic lunches before returning to sign off on bats and then load the car with gear. We are close mates to this day and often reminisce about Basil D’Oliveira and Alfred Jameson’s quirky little sports shop in Soho. In seventeen years as a professional cricketer, I never used any other make of bat.)

After lunch we went back to the nets and I was told to pad up. With a beating heart, I took guard at Hampshire County Cricket Club for the first time. The net pitches were grassy and soft. ‘Herbie’ (Richard Elms, a left-arm quick who had just been signed from Kent) made a fool of me. In fact, in general, I made a fool of myself.

Nerves have never served me well. I completely disagree with the theory that you need at least a sign of nervousness to perform at your best. This has not applied to me in any walk of life. Not at the wicket; not on the tee; not in front of the camera, on the stage or at the lectern; never at a party, nor in a meeting; and definitely not with women. Nerves are my enemy and surely were this day at Northlands Road. The surface was difficult. The ball moved around off the seam and refused to come onto the bat. I missed it, nicked it, slapped it in the air, shut the face on outswingers to lose my off stump and got bowled through the gate by inswingers. It might be the most excruciatingly embarrassing twenty minutes of my life.

I could sense the disapproval. After the net session we were to drive to Dover and then play the Kent 2nd XI in a three-day match the next day: the biggest game of my life. Mike Hill told Sainsbury they couldn’t possibly leave a staff player behind and take me. Others whispered in corners with a similar sentiment. Andy Murtagh sensed the general unease, told everyone to pack their gear and that he would have the travel arrangements for the journey to Kent fixed in half an hour. Then he took me aside and told me to forget about the net session. Tomorrow was another day, he said. Murtagh’s brother, Paul, taught at Bradfield. Perhaps he had heard I was all right. Sainsbury came into the dressing room and confirmed I was playing. I suspect he was under orders from the Eagar–Gilliat corridor of power.

In those days, we travelled to matches by car. Quite how any of us afforded a car, I don’t know. Popplewell wasn’t with us at this stage; he was still up at Cambridge bowling those medium pacers for top county players to batter around Fenner’s, the university ground. Murt drove Jungle Rock and me, in the back seat, to Dover.

That week, the back of the passenger seat in Hillers’ car broke, so Freddie Ireland, the scorer, who always travelled with Hill, lay down all the way to Dover and back. Freddie couldn’t pronounce his Rs and, for that matter, wasn’t much good with Fs either. So he called himself ‘Pweddie’, which we all did, and it was bloody funny. We used to tick-tack en route, stopping at a pub or fish and chip place for supper. All these old bangers, bought on the cheap, in a peloton to far-flung parts of the land for cricket games that no one watched and of which few took notice. Pweddie liked fish and chips and told Hillers to stop near Canterbwe at a chippy he had known since god was a boy for pish, chips and mushy peas. Certainly, said Hillers, so that is what we all did, in town after town, month after month, during the summer of 1977.

The following year, I shared a house with Hillers. He ironed his socks and underpants, and made sure his trousers had a perfect crease. He left his bathroom gear—toothbrush, paste, shaving kit and so on—in symmetrical lines. If you knocked something out of place, it would be realigned when you returned. He was always bathing or showering. Super bloke, ordinary cricketer. And he never got the seat fixed. Pweddie had to travel thousands of miles lying flat on his back.

In August, Elvis Presley died. When Hillers came to pick up Pops and me to go to a game in Bournemouth (quite how we fitted in with Pweddie spread-eagled in the passenger seat I don’t know) I was on the staircase inside the front door doing ‘Blue Suede Shoes’—voice, knees, air guitar, the lot—and given my long dark hair and the pound or two of excess weight I was carrying, it was an easy call. I was Elvis for the rest of the summer.

Elvis made a hundred at Dover. Kent were strong, as were we. The cricket was a good standard, much the best I had played. And I made a hundred, which was orgasmic. Chris Cowdrey got one for Kent, too. It was the first time we had met and we had a terrific night out, whizzing into town in his black Ford Capri. The girls loved him. Everybody loved Cow. There was a magic about him.

My hundred shook the boys up. Nick Pocock (Pokers—as I say, we cricketers could sure cook up a storm with nicknames) was another of the public schoolboys flirting with cricket as a living. He was a good front-foot driver of the ball and a brilliant catcher anywhere close to the bat. He made a hundred too. We were out soon after one another, and as the others took us past 350, he walked me around the ground.

‘It’s pretty obvious you can play a bit. You’ll probably get offered a retainer for the rest of the summer,’ said Pocock. So far so good. ‘But be careful, the long-time pros think you’re cocky. Turning up and making runs doesn’t make life comfortable for any of them. Keep your head down and for god’s sake don’t sound like you know it all, even if you do. Though you don’t.’ Right. Blimey. Not how I had imagined life as a pro at all.

Pocock was spot on. They sure thought I was cocky and they were right, though it wasn’t a conscious thing. I was enthusiastic and had spent most of my life in love with the game. I read every book and watched every televised ball. By the standards of most nineteen-year-olds, I knew a lot about cricket. The challenge was to not let anyone know. I was offered a retainer—£21.50 a week—for the rest of the summer.

And that was pretty much how we rolled. Hours in the nets. Not enough fielding practice. Unhealthy food. Lots of beer. Long car journeys, often at night after matches. Stops in provincial English towns and villages. (Pokers refused to stop at motorway services for any reason except fuel. He said Ingleby wouldn’t dream of it—‘Ghastly places.’) Fines for just about any indiscretion that included dropped catches and not wearing the club tie after play, along with daft ones such as the failure to drink anything and everything with your opposite hand on a Friday.

(After the offer of a retainer, I couldn’t afford the bed and breakfast full time, so Sains and his lovely wife, Joyce, put me up at their home. Every morning, he would bring me in a cuppa, with a ‘Wakey, wakey, rise and shine’. On Friday mornings, as I yawned and knocked back the tea, with the cup in my usual right hand, he would exclaim ‘Got ya, 50p!’ One day, Dougal threw his toys out of the cot when he was battling away to save us the game and at the tea-break slugged back a pint of orange squash only to be told it had cost him fifty pence. Believe me, enough little mistakes and £21.50 a week didn’t go far, especially if you couldn’t catch.)

We won a few games and lost a few. It felt special to represent Hampshire, and a place in the 1st XI remained the Holy Grail. When Rock was picked to play at Portsmouth, we all went along to watch him. There were a few thousand spectators at the United Services ground and our boy briefly looked the goods. The sun shone that day and all was well with the world.

The biggest thrill of the summer came in mid-June at Northlands Road, where Hampshire had a home semifinal tie against Gloucestershire in the Benson & Hedges Cup. A few of us watched the game from inside the scorebox, urging on those of our number—Ricey and Dougal most notably—who were playing.

If Barry Richards was the cricketer on whom I most doted, Mike Procter was not far behind. His buccaneering style, both on and off the field, mesmerised opponent and spectator alike. He and Richards had grown up in Natal at the same time, and both played for the Gloucestershire 2nd XI after impressing on a South African schools tour to England in 1963. Procter is one of only three men—Sir Donald Bradman and C.B. Fry are the others—to have made six consecutive first-class hundreds. But it was as a fast bowler that he most caught the eye, sprinting in from near the sightscreen to bowl with an unusual, almost wrong-footed action and swinging the ball prodigiously in to the right-handed batsmen.

Procter won that semifinal almost before it had started. He took four wickets in five balls, including a hat-trick. And not any old four, if you don’t mind. He trapped Richards and Jesty lbw, and bowled Greenidge and Rice. He had Cowley stone dead lbw for five in six but dear old Tommy Spencer’s heart was pounding too much to get his right forefinger out of the holster for a third time in one over. As Cowley says to this day, he was the most out of the three of them. Watch it on YouTube: it is as captivating now as it was then. Imagine seeing and hearing this drama from the scorebox. We couldn’t change the tally fast enough. The chants of ‘Proctershire, Proctershire’ live with me to this day.

Inspired, I took to bowling in the nets like Procter and batting with my chin tucked into my left shoulder like Richards. I imitated their voices too, having edged close enough to Procter in the bar that June night to hear every word. Neither playing method much worked as I recall but mimicry was to become a common theme over the months and years that followed, especially of John Arlott and Richie Benaud.

Pops and I won Sains over, and Hillers began to enjoy our happy-go-lucky look at life. Paul Terry (PT—I know!) teamed up with us for the second half of the summer after finishing at Millfield and playing a lot of representative cricket for England at Under-19 level.

It was an awful feeling when summer turned to autumn and we were sent on our way. In those days, and until fairly recently, county contracts applied to the period from April through to September. We said goodbye to friends and went out into the big wide world to find a job. I headed back to London, lived with Mum, and ended up in the City doing analyst work with the stockbroking firm Hoare Govett. As the days became shorter and the nights longer, I was overcome with the desire to return to the little downstairs dressing room at Northlands Road and the banter that had quickly become a soundtrack to my life. I missed bat and ball and I missed the people. I missed the way cricket had wrapped its arms around me. I knew there was no going back, no chance of a life in the City or anywhere else except Northlands Road. I had been offered a two-year contract and I was damned if I wouldn’t make it work.

CHAPTER 3

Australia

In the late English summer of 1978, Mike Taylor, the experienced Hampshire all-rounder, asked me if I fancied a season in Australia. Kerry O’Keeffe, who had spent a period at Somerset with Mike’s brother, Derek, had been on to him about a young pro playing for a club he knew that needed shoring up. I could barely contain myself.

Come season’s end, I packed a couple of bags and set off on the second real adventure of my life. Two winters earlier, I had captained an English Schools team, under the name the Dragons, to Rhodesia and South Africa. We had some success and after the tour I took the overnight train to Durban to play three months of club cricket for Berea Rovers. I was eighteen, hung out at the youth hostel in town, and lived the life of a young man besotted by cricket and the avenues down which it led.

But the dream was different. I had a cinematic vision of Australia, in which the blue horizons cut a sharp line between sea and sky and where the terracotta desert stretched so far from view that no man could ever occupy its space. My father had told me about Richie Benaud, my mother about Keith Miller. I had seen Dennis Lillee at Lord’s and Jeff Thomson at Southampton. The Chappells had spent many a summer’s day in the garden at home in London, and on many a winter night their deeds had been transmitted via radio to a little boy who could repeat their figures more easily than his times tables.

The Australian captain’s wicket had been the greatest prize, both at home and on the telly. It was a love–hate relationship. I could mimic Ian Chappell’s stance, and his back-and-across move to play the hook. I could chew his gum, reposition his box and tug on the brow of his baggy green cap. The buttons of my shirt were undone to the breastbone, the sleeves were turned up at the cuff, the collar pointed to the sky. I could run in like Lillee, leaning well forward, pumping my arms and reaching the crease with a raucous surge of momentum. I could scream his appeals on my haunches, a finger raised to the heavens and a look of disgust at the umpire’s decision. And I could wipe the sweat from my brow with a single swipe of my right index finger. Only Chappell and Lillee could stop Dexter, Boycott, Higgs and Snow in the backyard of 106 Priory Lane, London, SW18.

During Ashes tours Down Under, I would listen to the wireless until the small hours claimed me. In 1970–71, I heard Alan McGilvray and John Arlott talk of Ray Illingworth and Bill Lawry; of Snow and Terry Jenner; of Boycott and Johnny Gleeson; and of the Sydney Hill and the old scoreboard. Once, a mean teacher at boarding school left me bereft when he confiscated that wireless. It was returned when the rawness of the loss became apparent to the headmaster, Charles Brownrigg. He reasoned that a little boy’s tired mornings were a fair trade for enthusiasm and the knowledge of a game that he suspected would play a huge part in that boy’s life.

Through the northern winter of 1974–75, we watched highlight reels of Lillee and Thomson doing terrible things to English batsmen. One ball from Thommo hit Keith Fletcher on the badge of his cap and flew 25 yards to cover, where Ross