2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Splendid Publications Limited

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

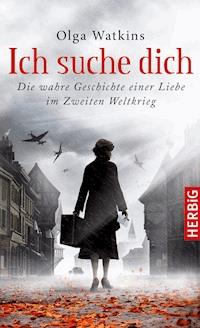

The true story of a woman's incredible journey into the heart of the Third Reich to find the man she loves. When the Gestapo seize 20-year-old Olga Czepf's fiance she is determined to find him and sets off on an extraordinary 2,000-mile search across Nazi-occupied Europe risking betrayal, arrest and death. As the Second World War heads towards its bloody climax, she refuses to give up - even when her mission leads her to the gates of Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps...Now 88 and living in London, Olga tells with remarkable clarity of the courage and determination that drove her across war-torn Europe, to find the man she loved. The greatest untold true love story of World War Two.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

A Greater Love

Olga Watkins

With James Gillespie

Olga Watkins was born in Yugoslavia in 1923. She lived in Zagreb and then in Hungary before coming to Britain in 1954. She worked as a nanny, a chef, head linen-keeper at the Devonshire Club in St James’s and as a dress-maker for Hardy Amies, Liberty and Jaeger. She lives in north London with her husband, Gerry.

James Gillespie is a journalist who has worked for The Independent, The Mail on Sunday, The Daily Mail and The Daily Telegraph. He lives in Kent with his wife Pauline and children Liam, Daniel and Matthew.

Published in 2011 by Splendid Books Limited

Written by Olga Watkins with James Gillespie

Copyright © 2011 Splendid Books Limited

The right of Splendid Books Limited to be identified as the Author ofthe work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright,Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Splendid Books LimitedThe Old Hambledon Racecourse CentreSheardley LaneDroxfordHampshireSO32 3QY

www.splendidbooks.co.uk

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form including onthe internet or by any means without the written permission of thepublisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or coverother than that in which it is published and without a similarcondition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from The British Library

ePub ISBN: 978-0-9569505-1-2

Commissioning Editors: Shoba Vazirani and Steve ClarkEditor: Amber Ross, Coordination: Annabel Silk

Designed by Design Image Ltd.www.design-image.co.uk

Printed in the UK

Every effort has been made to fulfil requirements with regard toreproducing copyright material. The writers and publisher will be gladto rectify any omissions at the earliest opportunity.

Photo credits: Olga’s own collectionContemporary photographs: James GillespiePage 210 picture: Courtesy of The Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora Memorials FoundationRoute map: Anthony Graham / www.illustrativemaps.co.uk

Inhalt

Olga's Journey

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Epilogue

Splendid Books...

More from Splendid Books...

Olga’s Journey

1. Zagreb – Osijek (173 miles)

2. Osijek – Budapest (156 miles)

3. Budapest – Osijek (156 miles)

4. Osijek – Zagreb (173 miles)

5. Zagreb – Vienna (224 miles)

6. Vienna – Budapest via Veszprem (196 miles)

7. Budapest – Komarom (60 miles)

8. Komarom – Vienna (104 miles)

9. Vienna – Nuremberg (311 miles)

10. Nuremberg – Munich via Passau (261 miles)

11. Munich – Dachau (10 miles)

12. Dachau to Erfurt (242 miles)

13. Erfurt to Buchenwald (15 miles)

Total: 2,081 miles

CHAPTER ONE

I looked around, my eyes wide with amazement. There was water everywhere. It covered the entire ground floor of our tiny house and was lapping at the first step of the staircase. I gingerly put one foot down into the water. It was freezing. I hurriedly hopped back onto the stairs.

Thrilled, I screamed: ‘There’s water in our house!’

My mother replied from upstairs: ‘Olga? What are you talking about?’

I heard her footsteps on the landing and then clattering down the stairs behind me, stopping when she saw the water. My mother groaned and looked close to tears.

I still couldn’t believe my eyes – where had all this water come from? The answer, of course, was from one of the three rivers – the Sava, the Kupa and the Odra – which converged in my hometown of Sisak in Yugoslavia. My house was just one of hundreds hit by floods that day in 1926.

For the children it was an exciting diversion – the older ones had a day off school and we all had the chance to float along the streets in makeshift canoes, waving to friends. For a three-year-old girl like myself, it was hard to imagine anything more exciting.

For adults it was a burden, but a familiar one. The rivers that meet in Sisak, 35 miles south-east of Zagreb, were good for business in the town but not so great for keeping the place dry. Even today, Sisak has few buildings of any note, apart from its medieval castle set on higher ground in the old town.

As my parents began clearing up, they could be forgiven for cursing the waters. My father, Josip Czepf, had particular reason to feel aggrieved. He had invested in high-quality timber from the local factory to clad the walls of our dining room and now the bottom of each plank was soaked. The damp was rising swiftly. He resolved to move to a house on higher ground – but only when he found one with a dining room large enough to take his timber cladding.

A fastidious man who worked as an accountant at a local factory, he was determined that such expenditure would not go to waste. My mother, Slava, who worked for the same company in the sales department, would be so disappointed.

They had met eight years earlier when she was a translator at the Shell refinery in Caprag, a suburb of Sisak, where he was employed in the accounts’ department. Tall and striking, with piercing green eyes and youthful energy, she had immediately attracted the attention of Josip. He was eight years her senior and a big, powerful man. He was tall with a full head of dark hair, a moustache, piercing brown eyes and a commanding presence. They married when she was just 19 and I was born the following year, on March 20th 1923.

Sisak was a quiet town and we were regular worshippers at the Holy Cross Catholic church, where my mother sang in the choir.

Many of my mother’s relatives lived nearby - either in the town itself or on farms in the surrounding countryside. Her mother, Amalia, was a frequent visitor. A tall, elegant woman, she loved seeing me, but didn’t feel the same about her son-in-law, Josip, with whom she frequently clashed on matters ranging from the domestic to the financial.

By 1929, I was six years old and our family was comfortably off, with a house close to the town centre - on higher ground this time. I was making friends at the local school and always felt proud when my mother came to collect me. She looked so beautiful and stood out from the other mothers. All eyes were on her and, if anyone asked, I would puff myself up and say: ‘That’s my mother.’

As time passed, my grandmother grew increasingly infirm. An independent woman, she lived alone, but that year she suffered a stroke, which left her paralysed on the left side of her body. She could no longer look after herself and we made plans for her to move in with us.

My father was far from keen, but there was no alternative, so my grandmother arrived and took up residence in a bedroom at the back of the house. The stroke had not stilled her tongue and the conflict with my father resumed almost immediately and was unrelenting.

I, however, was glad of the company and frequently took refuge in my grandmother’s bedroom, reading to her and being taught German in return.

If we felt our bad luck for the year had been used up with my grandmother’s stroke we were mistaken. The Wall Street Crash may have happened on the other side of the world, but the shockwaves were felt even in Sisak. My mother’s family saw many of its investments wiped out and farm prices collapsed. In common with many others in the inter-war years our comfortable, middle-class family suddenly found itself living in considerably reduced circumstances.

Tensions in our house between my father and my grandmother increased. Something would have to give – and one day it did.

My mother returned from shopping in the local market to find the house quiet. She checked grandmother’s bedroom and found her sleeping peacefully. I was out with friends, but where was Josip?

In the kitchen she found a hand-written note from him declaring that he had had enough of caring for her mother, that the constant arguments had become too much to bear and he was leaving. If circumstances were to change, he might return.

Beside herself and still clutching the note, my mother ran out into the street as if expecting to see her husband standing there. She asked the neighbours, but no one had seen Josip. She tried the factory, but his workmates knew nothing. Forlorn, she returned home to find me at home, chattering to my grandmother. Josip had simply vanished.

Aged about two, with my mother.

This dramatic change in the family left me relatively untroubled. While my mother struggled to see how we would survive, I had always found my father rather distant and forbidding and readily turned to my mother’s family for comfort. The German lessons in the upstairs bedroom continued apace and relatives offered financial support, most of which my mother felt too proud to accept. But, in truth, I enjoyed my new life.

My uncle Drago ran a restaurant on the banks of the river Kupa, which frequently played host to some of Sisak’s most important citizens. Every day, there was a barbecue and I would run to the restaurant as soon as school had finished to enjoy the lamb’s head that Drago had saved for me. Drago looked forward to the moment I appeared: the rest of the family had sons – I was the only girl.

Despite her best efforts, my mother could not find my father. He had left us with no money and it was impossible to claim maintenance without knowing where he was.

She continued with her work at the factory, but the domestic help she employed to look after me and my grandmother never stayed long. Eventually, my mother quit her job and turned to embroidery to make a living. A skilled seamstress, she could work at home and, what’s more, I could help her. So at the age of just seven, I was taught the skills and intricacies of embroidery.

By 1930, electricity had yet to reach the homes of Sisak, so we would work late into the night by the light of a petrol lamp placed high on a cupboard, to prevent the flame catching any of the fabric. The lamp cast a yellow glow over the long table at which we worked. I would sit on a saucepan balanced on the seat of a chair to bring me up to the height of the table, stitching one end of the cloth while my mother embroidered the other end. I learnt quickly and we chatted like old friends as we worked, our heads bowed over the material, fingers flicking quickly in the lamplight. We paused in the evening to eat a salami sandwich before picking up our needles again.

Life wasn’t just work, though. One of my uncles owned a large farm on the outskirts of the town, and I would often help him to take food out to the workers in the fields in a fiacre. He would whip the horses into a gallop and we would rattle along the country lanes with me hanging on for dear life until he slowed the horses and pulled up at a barn or gate. Then I would jump down clutching a parcel of food, run to the foreman in charge and hand it over. The rich, warm smell of the salami in the packages always left me feeling hungry and I envied the working men their food.

In the winter, when the landscape was covered in a blanket of snow, our faces would be stung by the cold as the horses kicked up their own snowstorm. My uncle would wrap me in a fox fur stole before setting off. ‘I feel so special when I’m there in my fur in the fiacre,’ I told my mother.

In common with many children of that era, I had to grow up fast. Soon I was doing the family shopping at street markets, haggling over the prices of cheese, eggs, fruit, vegetables and live chickens. I soon learnt to put the live chicken on the ground and press it with my foot to test for the quality of the meat. The stallholders would tease me: ‘Oh, Olga, you’re too smart. Why don’t you buy this scraggy old chicken instead?’

On Sundays my mother and I went to church and had Maryland chicken and apple cake afterwards. During the milder weather between April and October, we would head out into the countryside for picnics. Sitting lazily on the grass, she taught me how to make daisy chains and told stories of her youth.

Pictured with my father around 1925.

By 1933, life had settled into a routine. There were no luxuries but we survived. The fact that 750 miles away in the German capital of Berlin, Adolf Hitler had just been appointed Chancellor was a matter of the utmost indifference. Yugoslavia’s tiny German population may have been excited, but what possible effect could it have on us? No, there was too much in daily life to worry about - the rest of the world would have to look after itself. In fact, that year I had to face a new problem of my own.

I was just ten years old when one night, leaning over my embroidery, I found myself struggling to see clearly. The neat stitches swam before my eyes. The edges blurred; the colours ran together. I blinked and rubbed my eyes. It felt as if I had pieces of grit in them but rubbing only seemed to make it worse.

Over the next few weeks, my eyes became increasingly painful and my sight deteriorated rapidly. Every time I blinked, it hurt. Our local doctor referred me to an eye specialist in Sisak who, also baffled by the condition, referred me to a clinic in Zagreb.

‘They have better equipment and medicine there,’ he told my mother. ‘They’ll be able to help you.’

My mother and I caught the train for the 35-mile journey to Zagreb for a series of medical appointments. For me, the train trip was a new world, full of surprises. Peasants would clamber on board with livestock in their hands or tugged behind them on a rope. Everyone seemed to carry vast quantities of food. Wine was transported in huge flagons which were liable to break when the rattling and jolting of the train sent them crashing against the sides of the carriage. Loud wailing and recriminations followed the breakages.

While most of the passengers headed off to the markets of Zagreb, my mother and I would go to the clinic. I was excited by the bustle and crowds of the city, but despite the optimism of the Sisak doctor, the specialists in Zagreb were no closer to finding the cause of my failing eyesight than he had been. Various treatments were tried, but the condition stubbornly refused to clear up. My excitement over the visits to Zagreb was quickly replaced by fear: my world was shrinking all the time.

‘Am I going to go blind, Mummy?’ I asked.

‘No, of course not, the doctors will cure you,’ she replied, hiding her concern and wondering where help would come from.

The payments for travelling and treatment were a heavy burden on my mother, who had precious little money to begin with and now had lost her embroidery assistant. She was forced to sell her best furniture and jewellery.

I had to wear dark glasses to protect my weak eyes and could no longer go to school, so I spent my time sitting in a chair outside the house, listening to other children playing. The days of running to Drago’s restaurant to eat lamb’s head and riding in fiacres with my uncle were long gone. Now, my dark world was one of very limited horizons.

I was very scared. Losing your sight is a terrifying prospect for a child and I cried often, fearful for my future. My mother was in despair. We had tried the best specialists in Zagreb, virtually bankrupting ourselves in the process. If they couldn’t cure me, then who could?

Help, when it came, arrived quite by chance.

A woman visiting another family in our street saw me sitting in my chair, my eyes hidden behind dark glasses, and asked me what was wrong.

I explained, and the woman, who gave her name only as Mrs Brun, asked to have a look at my eyes. She studied them carefully and then from a jacket pocket produced a small magnifying glass. She examined them some more.

‘I think I know what’s wrong,’ she said.

‘You do?’ I asked.

‘Oh, yes, I think so. Is your mother or father here?’

‘My mother’s inside,’ I said jumping from my chair and rushing into the house, shouting.

Mrs Brun explained to my mother that she believed the problem was caused by the fact that I had not one, but two rows of eyelashes, a condition known today as distichiasis. In addition, one of the rows was growing inwards, touching the cornea, known in the medical world as trichiasis. Every movement of the lid was injuring the whites of my eyes and causing bleeding. It was – and remains – a rare condition and in those days was virtually unheard of. Diagnosis is made all the more difficult because the secondary row of lashes frequently has no pigmentation and is difficult to see.

Luckily Mrs Brun believed she could treat my eyes. She returned for two visits, in which she used oil and tweezers to remove the lashes. The pain was intense and there were moments when I wept and wondered whether so much pain could really cure me. But, within a week, my eyesight was clearing and I could blink normally without discomfort.

Mrs Brun visited again and seemed pleased with my progress. I thanked her profusely and my mother offered what payment we could muster. It wasn’t much. Mrs Brun refused the money and wished us well. We never saw her again.

***

Letters were not frequent in our household and the arrival of one always caused a frisson of excitement. I looked forward to the opening of any letter with eager, childish anticipation, while my mother had an adult’s dread of them – fearing demands for payment and bad news.

The letter that arrived one day from Zagreb, written in careful, neat handwriting contained some sensational news – for both of us. It was from a friend of my mother called Helga, who worked at the main post office in Zagreb. Sorting post a few days previously she had come across an envelope addressed to a ‘Josip Czepf’ and wondered if it was my missing father.

Helga had made a note of the address and my mother instructed a lawyer in Sisak to find out whether it really was Josip – and if so, to begin legal proceedings for the four years of maintenance payments that he owed us.

It didn’t take long to uncover the truth. My father was now working as a chief accountant in an asphalt factory, Res, in Zagreb and living with a wealthy Hungarian Jewish woman, Ilona Ungarl.

The legal proceedings were concluded swiftly and the family court in Zagreb ordered Josip to pay four years’ maintenance, plus allowances. It amounted to a substantial sum and he never forgave my mother for taking the action.

It did, however, make life easier for us at home in Sisak. With my return to school and the money finally arriving from my father, it seemed as if our fortunes were finally looking up.

Then, as the cold of winter gripped the town in 1934 and stretches of the rivers froze, my grandmother fell ill. I was then 11 years old and could only watch as doctors came and went. I heard their heavy footsteps on the stairs and their muttered conversations outside my grandmother’s bedroom door. No one told me what was going on but for some reason I felt sure my grandmother was going to die.

At the beginning of December, the temperature fell well below freezing. The countryside was shrouded in white and icicles hung from the rafters of every house. On December 3rd, in her bedroom at my home, my grandmother slipped into a coma.

I was taken up to see her. The old woman lay still and pale, her eyes closed. Never again would she talk to me in German; ask me about my day at school or curse my father for his fecklessness. I touched her hand, painfully aware of the wafer-thin skin and the fragile bones, before kissing her softly on the forehead.

Three days later, on December 6th 1934, grandmother Amalia died at the age of 72. In keeping with local tradition the funeral was held within 24 hours. The family gathered and as they filled the church pews I looked around and saw Drago and my farmer uncle who had driven the fiacre at a furious pace, and so many cousins.

They all came back to the house after the service and the hubbub of adult voices filled the rooms. I ran between the groups, talking to people, receiving words of sympathy and catching snatches of conversation.

Entering one room, I overheard my mother talking to a friend, Anna. ‘You know, Anna, I feel I’ll be the next to go,’ she said.

‘Oh, stop it,’ said Anna. ‘After all these problems with Josip resolved and your mother’s illness, now you can start a new life. Forget this talk about death, you’re only 33. You have your daughter to live for.’

Then they noticed that I was there and turned, all smiles, towards me.

Later, when most of the family had gone, Anna stayed on. My mother gave me some playing cards and I sat with the two women and began laying out the cards. The room was warm and after the excitement of the day, I soon began to feel tired and dozed on the floor. Between waking and sleeping, I heard some of the conversation.

At one point my mother confessed to Anna: ‘I worry that Olga will never get married. She is so thin and ugly.’

The remark wounded me deeply. Was I really so ugly? For days afterwards I would stare at my reflection in the mirror, examining my lips, eyes and dark hair. If I was really as ugly as my mother said, what could the future possibly hold?

***

In July 1936, Sisak enjoyed a heatwave. All the children played along the riverbanks; the bolder ones swimming in the cool water while others played in the streets or headed into the country for family picnics. The pavement cafes were busy, the men taking the opportunity for lazy days spent drinking.

For women, the weather offered the chance for spring-cleaning and on July 20th, my mother started on the carpets in our house, taking them outside to hang on a fence and beating them until clouds of dust covered her.

‘Olga!’ she called. When I went to her, she handed me some small change: ‘Go and get us some milk.’

I took the money and ran out of the house, glad for an excuse to be outside in such hot weather and to see other people. By then, I was 13 years old and as I walked to the shop I was greeted by market traders and shopkeepers, who knew me from my weekly shopping.

‘Ah, Olga, come and spend your money here!’ they cried. I smiled and waved, continuing on my way to buy the milk.

Afterwards, I walked slowly around the familiar streets, greeting people, chatting with my friends, stopping to play from time to time.

I certainly didn’t hurry home but as I was walking slowly back up our street, a neighbour suddenly appeared looking scared.

‘Go quickly, find the doctor!’ she shouted. ‘Your mother is very sick.’

I put down the milk and ran to the doctor, who came back to the house with me. Neighbours had taken my mother inside and laid her on a bed. The doctor took her temperature and turned to me: ‘Fetch your Aunty Tonka – quickly!’ Once again, I set off running and once again, just as it had been with my grandmother, I felt the adults weren’t telling me everything.

Aunty Tonka – my mother’s sister-in-law – came back to the house but closed the door when she went in to talk to the doctor, leaving me outside the room. Through the door, I heard them speaking in hushed tones. Eventually, Tonka emerged and led me into the sitting room.

‘Your mother is very ill,’ she said. ‘She has pneumonia and has to go to hospital in Zagreb; they have better medicines there than in Sisak.’

I remembered how I’d been told that before – and it hadn’t been true then.

An ambulance arrived and I watched as my mother was carried out of the house and carefully placed in the back before it moved off slowly down the street. Aunty Tonka stayed with me, but we said little. ‘Your mother is very dangerously ill; the doctors don’t know yet if she is going to survive,’ Tonka explained.

I was devastated. My mother and I shared a bond more like sisters than mother and daughter; a closeness forged during those long nights together working on our embroidery and the summer picnics in the country. My mother cared for me and loved me. Without her, what did I have? Nothing.

That night, I cried and prayed. ‘I’m only 13. Please don’t take her,’ I whispered in the darkness.

The next day came shattering news. Tonka said she could not stay to look after me – she had to work and take care of her own family. Instead, I was to be sent to Zagreb to stay with my father until my mother recovered.

My father? I hadn’t seen him since I was six years old when he abandoned us. The prospect filled me with dread.

The train journey to Zagreb this time held no excitement for me; instead I was full of foreboding. Tonka came with me and when we reached the station a couple were waiting for us. I was introduced to my father for the first time in seven years. With typical teenage truculence, I refused to say hello. Beside him was a short, fat and plain-looking woman, not at all like my tall, elegant mother. This was Ilona Ungarl. Josip was then 41-years-old while Ilona was 49; to me they both looked so old compared with my youthful mother.

Outside the station a chauffeur-driven car was waiting. Nobody spoke on the short journey to my father’s home, a house standing behind the walls of the factory where he worked.

It seemed as if, in that short journey, my life changed irrevocably. I had no friends in Zagreb, no cousins, no kindly uncles – and factory walls surrounding me.

Life in the Zagreb house was stiff and formal. Furthermore, I was living with strangers. My father was aloof and clearly not thrilled to find himself suddenly caring for a wilful 13-year-old while Ilona seemed to resent everything about me.

I was given a small room at the back of the house with a window that gave a cheerless view of the factory walls.

I couldn’t wait for my mother to recover and then we could return to our happy life in Sisak. My father spent all day at work, while Ilona took me to the shops. Our conversation was stilted and I made no secret of my dislike for the new woman in my father’s life. I spent the evenings in my room, alone, wondering about my mother. I asked my father for news. ‘If I hear something, I will let you know,’ he replied brusquely.

On the Saturday of my first week in Zagreb, July 27th 1936, my father suggested we all went to visit some friends for coffee. As we sat in silence behind the chauffeur on the journey to the friends’ house, we passed a hospital which I was convinced was the one in which my mother was being treated, although everyone else in the car was looking determinedly in the opposite direction.

‘There’s the hospital!’ I cried. ‘Let’s stop and go in and ask how mother is.’

‘Oh, come on,’ my father snapped. ‘We’ll be late for coffee and they are waiting for us.’

I slumped back in my seat, overwhelmed by sadness. I wanted to see my mother, but no one would let me. Why not? My fears were growing.

On the Monday morning, I was summoned to see my father in the sitting room. The curtains were partly drawn, casting deep shadows.

There was a long silence between us before he broke the news I had been dreading: my mother had died on Saturday morning.

Stunned, I went back over the events of that day in my mind. If only they had stopped the car I could have seen her for the last time; I could have been with her and held her hand. I was too upset and angry to cry – I bunched my fists and stared at my father with a feeling of hatred. How could he have been so cruel?

That wasn’t the end of it. The funeral was to be held that very afternoon, but my father was not going; my ‘stepmother’, as he called Ilona, would take me instead. I could not believe what I was hearing. After all that he had done to my mother, he didn’t even have the decency to go to her funeral.

‘Why don’t you come to the funeral?’ I demanded.

‘You’re too young to understand.’

‘Have you told mother’s family about the funeral?’

‘No.’

Full of bitterness and fury, I ran from the room. For the rest of my life, I have never forgotten my father’s coldness that day.

In the afternoon, I dressed carefully and joined my ‘stepmother’ and two of her friends. They led me to the coffin before the service and opened it for me to see my mother for the last time.

I could not believe it was her. The fine black hair of which she had been so proud had turned white and although she was only 35 years old, her final illness had left her looking drawn and old.

Too quickly, they closed the coffin, but I demanded it be reopened so that I could say farewell. I put my mouth close to my mother’s ear and touched her face gently. ‘Goodbye, I love you,’ I whispered.

I stood back from the coffin and the other three women watched me intently. I was overwhelmed by emotions: grief, anger, despair – but I was too upset to cry. Later Ilona would tell friends: ‘Olga has no heart. She never cried for her own mother; how can I expect her to have feelings for me?’

A few days later, my stepmother and I travelled to Sisak to collect my belongings and clear out our house. My mother’s family were appalled and angry that they had not been told about the funeral – and had only just heard about her death.

Drago hugged me to his chest: ‘My little girl, what is going to happen to you?’ he said. ‘If the worst comes to the worst, we will all help to keep you until you finish school.’

All our belongings were sold quickly. I was heartbroken to see the beautifully hand-embroidered table clothes and pillowcases, upon which my mother and I had worked so hard, being sold cheaply.

‘Can I keep something to take back with me to Zagreb?’ I asked my stepmother.

‘No,’ she replied. ‘You don’t need anything. When you need something, we will get it for you.’

I said my farewells to the family and places that had shaped my childhood, taking nothing with me but my own clothes.

As I was saying goodbye to Aunty Tonka, she slipped a diamond solitaire ring into my hand. ‘It was your mother’s,’ she whispered to me. ‘She would want you to have it. Here, take it.’

I put the diamond in my pocket and then rejoined my stepmother for the journey back to Zagreb. With one final glance, I gazed around me at Sisak and the people I had known and loved all my life. Would I ever see them again?

Not if my father had anything to do with it. When we returned to the house in Zagreb, he took me to one side and said: ‘Sisak is your past. Your new life is here in Zagreb. You will have a different life. You will not be poor any longer. You are going to have all you need. From now on, I want you to call your stepmother “mother”, as she will be looking after you.’

I did not reply but simply left the room, leaving my father staring after me.

Not once in my life did I ever call Ilona ‘mother’.

CHAPTER TWO

The Second World War took a while to reach us in Yugoslavia. We watched anxiously as Hitler’s forces conquered much of Europe and we worried for our own future. Stronger nations than ours had succumbed and our Hungarian neighbours had agreed a pact with the Germans. The signs were ominous and I often heard the adults talking in hushed tones about war and what it would mean for us. It was not just the Germans we had to fear. Mussolini, Hitler’s ally in Rome, had territorial ambitions too and had long cast covetous glances at our country.

The Yugoslav Prime Minister, Milan Stojadinovic, presided over a corrupt and failing system. Elections were far from secret – each voter had to declare their choice openly and have the vote entered against their name in the electoral register. It was commonplace for government candidates to offer gifts in return for votes. In some areas, officials bribed voters with a pair of opanke (slippers) - one being handed over before the election, the matching one being given after the vote. Civil servants frequently lost their jobs if they voted for the opposition.

The country was showing all the signs of a nation on the point of fracturing. The enmity between Serbs and Croatians had been with us for generations and was growing steadily worse. Belgrade, the capital, was a Serbian stronghold while our city of Zagreb, the capital of Croatia, had become the focus of demands for a separate state*.

* The attempt to unite six Balkan states in the nation of Yugoslavia began in 1918 in the wake of the First World War. The borders of the new country (although it didn’t take the name Yugoslavia until 1929) were established on 1 December 1918. It encompassed six states: Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro and Slovenia. Conflicting nationalist aspirations meant it stumbled from crisis to crisis until 1941 when it was invaded by Germany, Italy, Hungary and Bulgaria. The new rulers divided up the nation again, installing a puppet regime in Zagreb, where Ante Pavelic and his Ustasha party ruled the new Independent State of Croatia while a German Military Administration ruled Serbia from Belgrade. Bosnia was ceded to Croatia; Macedonia was taken over by Bulgaria; Montenegro went to the Italians and Slovenia was divided among Germany, Italy and Hungary.

Resistance to the invaders united around Josip Broz, who took the name Tito. Although a committed Communist, his partisans won the support of the Allies as well as the Soviets and at the end of the war, in 1945, it was Tito who took control of the re-formed nation of Yugoslavia. His brand of independent, liberal communism gave his people a high standard of living and, unlike the rest of the Soviet bloc, citizens were allowed to travel to Western countries and even work abroad.

An alliance with Josef Stalin in Moscow lasted only until 1948 but Tito survived as leader until his death in 1980. Once he went, the end was inevitable. As the whole communist bloc crumbled in 1989, Yugoslavia shattered into warring nations and was finally wiped from the map.

In common with the rest of Europe, a homegrown fascist movement, the Ustasha, had sprung up in Croatia during the 1930s, led by one of its founding members, Ante Pavelic. It called for a Croatian state in which only ‘true’ Croats would be citizens and a society run on totalitarian lines similar to Germany and Italy. But although there were frequent battles with communist supporters, usually around the university in Zagreb, the Ustasha had little effect on us in our day-to-day lives.

By the time war broke out in 1939, Pavelic was living in exile in Italy, on the run from a death penalty handed down by a Belgrade court for anti-Serbian activities.

His chance to return came on April 6th 1941, when Yugoslavia was invaded by Germany, Italy, Hungary and Bulgaria. Ustasha supporters and the ethnic German minority in Yugoslavia helped the invading troops with acts of sabotage and by encouraging Croats to believe the invasion would bring independence for Croatia. It worked. When German and Italian forces entered Zagreb four days later they were greeted by cheering crowds. The ‘liberators’ had arrived.

In my home in the Res factory, however, there was no such joy. On the day the invading armies entered the city I had just passed my 18th birthday and was out walking our pet dog with Mrs Graf, a family friend. While Mrs Graf tried to control her own two large dogs, I ran ahead. Suddenly, the wailing of the city’s air raid sirens halted us both. Fearing we were about to be bombed, we ran back home. But there were no bombs, just silence.

All the family was gathered, waiting to hear what would become of our country, when there was a loud banging on the door. ‘Open up!’ a voice shouted.

Standing on the doorstep were two men smartly dressed in Croatian uniforms. ‘We are here to tell you that a new Independent State of Croatia has been declared,’ they said before turning and marching away.

Mrs Graf looked pale. ‘We are in danger now,’ she said to me, while my father simply remarked: ‘We have a new country.’ Out of nowhere, the streets filled with Italian soldiers. I sat watching these darkly exotic and good-looking men from the window, but was banned by my father from going outside to mingle with the crowds.

The following day the centre of Zagreb was deserted - a city awaiting its fate. My father spent the day creating hiding places in the house for the family’s precious hoard of gold.

Five days later Pavelic returned to Zagreb under the cover of darkness with a few hundred supporters, who spread themselves through the city and took control. Styling himself as Poglavnik’ – the equivalent of Fuhrer – he began ruling his now Independent State of Croatia with ruthless brutality.

Ustasha gangs roamed the country taking bloody retribution against their enemies in general and Serbs in particular. As a gesture towards Germany, they brought in anti-Semitic legislation, but they were initially more intent on targeting the Serbs in Croatia than persecuting the Jews.

An air of fear pervaded every street in the city. I was in my final year at the St Vincent de Paul private school, run by a French order of nuns, and my route to school took me along familiar roads. One morning, shortly after the Ustasha had assumed power, I saw what looked like a bundle of old clothes hanging from a tree. As I approached, still wondering why anyone would put clothes in a tree, I realised with sickening horror that it was the body of a hanged man. Further along the street was another, and then another.

I walked faster, my head bent, my eyes fixed on the pavement, the bodies hanging from the branches above me. By the time I reached the gates of the school, I was running.