8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

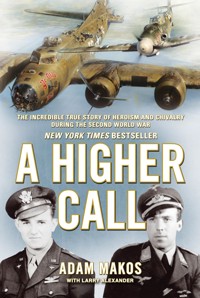

This instant Sunday Times bestseller tells the story of two fighter pilots whose remarkable encounter during World War II became the stuff of legend. Five days before Christmas 1943, a badly damaged American bomber struggled to fly over wartime Germany. At its controls was a twenty-one-year-old pilot. Half his crew lay wounded or dead. Suddenly a German Messerschmitt fighter pulled up on the bomber's tail - the German pilot was an ace, a man able to destroy the American bomber with the squeeze of a trigger. This is the true story of the two pilots whose lives collided in the skies that day - the American - 2nd Lieutenant Charlie Brown and the German - 2nd Lieutenant Franz Stigler. A Higher Call follows both Charlie and Franz's harrowing missions and gives a dramatic account of the moment when they would stare across the frozen skies at one another. What happened between them, the American 8th Air Force would later classify as 'top secret'. It was an act that Franz could never mention or else face a firing squad. It was the encounter that would haunt both Charlie and Franz for forty years until, as old men, they would seek out one another and reunite.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

A HIGHER CALL

Adam Makos is a journalist, historian and editor of the military magazine Valor. Makos has interviewed countless veterans from WWII, Korea, Vietnam and present-day wars. In 2008 Makos travelled to Iraq to accompany the 101st Airborne and Army Special Forces on their hunt for Al Qaeda terrorists.

Larry Alexander is the author of the New York Times bestselling biography Biggest Brother: The Life of Major Dick Winters, the Man Who Led the Band of Brothers. He is also is the author of Shadows in the Jungle: The Alamo Scouts Behind Japanese Lines in World War II and In The Footsteps of the Band of Brothers: A Return to Easy Company’s Battlefields With Sgt. Forrest Guth.

First published in the United States in 2012 by Berkley, an imprint of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

First published in e-book in Great Britain in 2013 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Adam Makos, 2012

The moral right of Adam Makos to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Photos on here are from the collection of Franz Stigler.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 9781782392538 Trade paperback ISBN: 9781782392545 E-book ISBN: 9781782392552

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

In a church graveyard in Garmisch, Germany, a headstone stands against the backdrop of the Alps. Mounted to the stone is a photo etched on a porcelain circle, an image of a farm boy hugging a cow. He was killed while serving in World War II. This book is dedicated to him and all the young men who answered their countries’ calls but never wanted war.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

1. A Stranger in My Own Land

2. Follow the Eagles

3. A Feather in the Wind

4. Fire Free

5. The Desert Amusement Park

6. The Stars of Africa

7. The Homecoming

8. Welcome to Olympus

9. The Unseen Hand

10. The Berlin Bear

11. The Farm Boy

12. The Quiet Ones

13. The Lives of Nine

14. The Boxer

15. A Higher Call

16. The Third Pilot

17. Pride

18. Stick Close to Me

19. The Downfall

20. The Flying Sanatorium

21. We Are the Air Force

22. The Squadron of Experts

23. The Last of the German Fighter Pilots

24. Where Bombs Had Fallen

25. Was It Worth It?

AFTERWORD

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

TO LEARN MORE

INTRODUCTION

ON DECEMBER 20, 1943, in the midst of World War II, an era of pain, death, and sadness, an act of peace and nobility unfolded in the skies over Northern Germany. An American bomber crew was limping home in their badly damaged B-17 after bombing Germany. A German fighter pilot in his Bf-109 fighter encountered them. They were enemies, sworn to shoot one another from the sky. Yet what transpired between the fighter pilot and the bomber crewmen that day, and how the story played out decades later, defies imagination. It had never happened before and it has not happened since. What occurred, in most general terms, may well be one of the most remarkable stories in the history of warfare.

As remarkable as it is, it’s a story I never wanted to tell.

GROWING UP, I had loved my grandfathers’ stories from World War II. One had been a crewman on B-17s and the other a Marine. They made model airplanes with my younger brother and me, which we invariably destroyed. They took us to air shows. They planted a seed of interest in that black-and-white era of theirs. I was transfixed. I read every book about WWII that I could get my hands on. I knew that the “Greatest Generation” were the good guys, knights dispatching evil on a worldwide crusade. Their enemies were the black knights, the Germans and the Japanese. They were universally evil and beyond redemption. For being a complex war, it seemed very simple.

On a rainy day my life changed a little. I was fifteen and living in rural Pennsylvania. My siblings, best friend, and I were bored, so we decided to become journalists. That day we started a newsletter on my parents’ computer, writing about our favorite thing—World War II aviation. We printed our publication on an inkjet printer. It was three pages long and had a circulation of a dozen readers.

A year later, my life changed a lot. It was the summer after my freshman year in high school when my neighbor, classmates, and teacher were killed. A great tragedy struck our small town of Montoursville called “TWA Flight 800.” Sixteen of my schoolmates and my favorite teacher were traveling to France aboard a 747 jetliner. They were all members of the school French Club. Their plane exploded, midair, off the coast of Long Island.

I had planned to be with them. I had initially signed up for the trip but faced a tough choice. My Mom had sold enough Pampered Chef products in her part-time job to earn a vacation for our family to Disney World. The only catch was that the Disney trip was the same week as the school trip to France. I chose Disney with my family. I was in Disney when the USA Today newspaper appeared on the floor outside our hotel room to announce the crash, 230 deaths, and the first reference to a shattered small Pennsylvania town. When I returned home, my parents’ answering machine was full of condolences. In their haste to identify who had gone with the French Club, someone had posted the roster of the students who had initially signed up for the trip to France, and my name was there.

The funerals were tragic. When school resumed, my neighbor Monica was missing from the bus stop. Jessica always boarded the bus before us, but she was gone. My best friend among any and all girls, Claire, no longer sat next to me in class. And Mrs. Dickey no longer led the lessons. She was a great lady, a lot like Paula Dean, the jovial Southern TV chef. When we picked our adopted French names that we would be called during class hours, I had picked “Fabio.” It wasn’t even French. But it was funny and Mrs. Dickey let me keep it. That’s the kind of lady she was.

Flight 800 taught me that life is precious because it is fragile. I can’t say I woke up one day and started living passionately and working faster to make some impact on the world. It never happens in an instant. But looking back, I see that it happened gradually. By the end of high school, my siblings, friend, and I had turned our hand-stapled newsletter into a neatly bound magazine with a circulation of seven thousand copies. While our friends were at football games and parties, we were out interviewing WWII veterans.

We continued the magazine in college and missed all the Greek parties and whatever else kids do in college, because we were meeting veterans on the weekends, at air shows, museums, and reunions. We interviewed fighter pilots, bomber gunners, transport crewmen, and anyone who flew. On our magazine’s cover we wrote our mission: “Preserving the sacrifices of America’s veterans.”

People began noticing our little magazine. Tom Brokaw, who penned The Greatest Generation, wrote us a letter to say we were doing good work. Tom Hanks met us at the ground breaking of the WWII Memorial in Washington and encouraged us to keep it up. Harrison Ford met us at the AirVenture air show in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. He read our magazine on the spot and gave us a thumbs-up. So did James Cameron, the director of Titanic, when we met him in New York City.

After college, we worked for our magazine full-time. We worked faster and harder because we knew the WWII veterans were fading away. As the magazine’s editor, I enforced our three journalistic rules: get the facts right, tell stories that show our military in a good light, and ignore the enemy—we do not honor them. As for that last rule, we never had to worry about ignoring Japanese veterans—there were none in America that we knew of. But the German veterans were different. We crossed paths with them, several times.

At the air show in Geneseo, New York, an old WWII German fighter pilot named Oscar Boesch flew his sailplane for the crowd. He did beautiful gliding routines at age seventy-seven. But did I ever go to talk with him when he stood by his plane alone? No way. In Doylestown, Pennsylvania, I met an old German jet pilot, Dr. Kurt Fox, at a museum unveiling of a restored German jet. Did I care what he had seen or done? Not a chance.

I read about Germans like them in my books, saw them in movies, and that was enough. I agreed with Indiana Jones when he said, “Nazis. I hate these guys.” To me, the Germans were all Nazis. They were jackboot zombies who gathered in flocks to salute Hitler at Nuremberg. They ran concentration camps. They worshipped Hitler. Worse, they tried to kill my friends, the eighty-year-old WWII veterans who had become my heroes.

But something began to puzzle me. I noticed that the aging American WWII pilots talked about their counterparts—the old German WWII pilots—with a strange kind of respect. They spoke of the German pilots’ bravery, decency, and this code of honor that they supposedly shared. Some American veterans even went back to Germany, to the places where they’d been shot down, to meet their old foes and shake hands.

Are you kidding? I thought. They were trying to kill you! They killed your friends. You’re supposed to never forget. But the veterans who flew against the Germans thought differently. For once, I thought the Greatest Generation was crazy.

I HAD NOT been out of college a year when I called an old American bomber pilot named Charlie Brown. I had heard of him and had sent him a magazine and letter to ask if I could interview him. Legend had it that Charlie’s bomber got shot to pieces and there was a twist, although I couldn’t quite catch the full story at first. Supposedly he had some unusual connection with a German pilot named Franz Stigler, whom he called his “older brother.”

Charlie agreed to an interview then he threw me for a loop. “Do you really want the whole story about what happened to me and my crew?” Charlie asked.

“You bet,” I said.

“Then I don’t think you should start by talking with me,” Charlie said.

“Really?” I asked.

“If you really want to learn the whole story, learn about Franz Stigler first,” Charlie said. “He’s still alive. Find out how he was raised and how he became the man he was when we met over Europe. Better yet, go visit him. He and his wife are living up in Vancouver, Canada. When you have his story, come visit me and I’ll tell you mine.”

I was about to make excuses and tell Charlie I had little interest in a German fighter pilot’s perspective, when he said something that shut me up.

“In this story,” Charlie said, “I’m just a character—Franz Stigler is the real hero.”

WHEN I BOOKED my ticket to Vancouver in February 2004, I had to explain to my young magazine partners why I was spending $600 of our limited funds to fly across the continent to break my own rule. I was going to interview, in my words, “a Nazi pilot.” I was twenty-three years old. I flew to Vancouver and took a cab into the Canadian countryside. It was raining and dark. The next morning I left my hotel to meet Franz Stigler.

I never envisioned that Charlie Brown had pushed me into one of the greatest untold stories in military history.

I ended up spending a week with Franz. He was kind and decent. I admitted to him that I thought he was a “Nazi” before I met him. He told me what a Nazi really was. A Nazi was someone who chose to be a Nazi. A Nazi was an abbreviation for a National Socialist. The National Socialists were a political party. As with political parties in America, you had a choice to join or not. Franz never joined them. Franz’s parents voted against the Nazis before the Nazis outlawed all other political parties. And here I’d thought it was in every German’s blood. I never called Franz a “Nazi” again.

AFTER MY WEEK with Franz, I flew to Miami and spent a week with Charlie. We had a blast and drank Scotch each night after my interviews. We published the story of Charlie and Franz in our magazine. Our readers loved it. So, in the next issue, we published a sequel to our first story. But this was not enough. Our readers wanted more. So I asked Charlie and Franz if they would let me write their story as a book, the tale of two enemies. They agreed.

Little did we know that the process of writing this book would span eight years.

What you’ll read in the following pages is built around four years of interviews with Charlie and Franz and four years of research, on and off. I say “on and off” because I was still busy with Valor Studios, the military publishing company that our once-tiny newsletter had become. I interviewed Franz and Charlie at their homes, at air shows, over the phone, and by mail.

Charlie and Franz were always gracious and patient. If I had been them, I would have kicked me out and said “That’s enough.” But Charlie and Franz kept talking, remembering things that made them laugh and cry. I must stress that I simply compiled this story. They lived it. Through the stories they told me, they relived a painful time in their lives—World War II—because they knew that you would someday read this book, even if they were not around to read the final copy themselves. This book is their gift to us.

In addition to the foundation of interviews from Charlie and Franz, dozens of other WWII veterans shared their time to talk to me and my staff—from “Doc,” the navigator on Charlie’s bomber, to a former fourteen-year-old German flak gunner named Otto. Three times my research took me to Europe, where much of this story is set. I toured bomber bases in England with eighty-year-old B-17 pilots and scaled Mount Erice in Sicily, searching for a cave that had once been a headquarters. I followed historians around fighter airfields and into musty bunkers in Germany and Austria. The archivists at the German Bundesarchivs, the National Archives of England, and the U.S. Air Force Historical Research Agency assisted me in finding rare documents.

I’ve drawn from my magazine adventures, too. The Air Force let me fly in a fighter jet with an instructor pilot to learn fighter tactics. I flew a restored B-17 bomber to feel how it responded to a turn and rode in a B-24 bomber, too. In September 2008, I flew into Baghdad, Iraq, in the cockpit of a C-17 transport. From there I traveled to Camp Anaconda to feel the desert’s heat and get a glimpse of a soldier’s life by accompanying them on patrols. I figured it was impossible to write about warfare without having ever heard gunfire.

What follows is the book that the old me, with my old prejudices, would have never written. When I first phoned the World War II bomber pilot named Charlie Brown, all I wanted was thirty minutes of his time. But what I found was a beautiful story worth every minute of eight years. The story has plenty of questions about the prudence of war and the person we call the enemy. But mostly it begs a question of goodness.

Can good men be found on both sides of a bad war?

Adam Makos

Denver, Colorado

September 2012

A STRANGER IN MY OWN LAND

MARCH 1946, STRAUBING, GERMANY

FRANZ STIGLER BURIED his hands in the pockets of his long, tattered wool coat as he shuffled along the streets of the small, bombed-out city. The frigid air crystallized his breath in the early morning sunlight. He walked with small, fast steps and hugged himself to keep warm against the wind.

Franz was thirty years old but looked older. His strong jaw was gaunt from weight loss, and his sharp, hawk-like nose seemed even pointier in the icy air. His dark eyes bore hints of exhaustion but still glimmered with optimism. A year after the war had ended, the economy across Germany remained broken. Franz was desperate for work. In a land destroyed and in need of rebuilding, brick making had become Straubing’s primary industry. Today he had heard the brick mill was hiring day laborers.

Franz scurried through the town’s massive square, Ludwig’s Place, his black leather boots clopping along the frozen cobblestones. The square faced east and welcomed the morning sun. In its center sat City Hall, an ornate green building with a tall white clock tower. The hall’s tall windows and carved cherub figurines shimmered. City Hall had been one of the few buildings spared. Around Franz, clumps of other buildings sprawled in the shadows, vacant and roofless, their window frames charred from bombs and fires.

Straubing had once been a fairy-tale city in Bavaria, the Catholic region of Southern Germany where people loved their beer and any excuse for a festival. The city had been filled with a rainbow of houses with red roofs, office buildings with green Byzantine domes, and churches with white Gothic towers. Then on April 18, 1945, the American heavy bombers had come, the planes the Germans called the “Four Motors.” In bombing the city’s train yards the bombers had destroyed a third of the city itself. Two weeks later, Germany would surrender, but not before the city lost the colors from its rooftops.

The clock chimed, its echo bouncing throughout the square—8 A.M. A line of German civilians extended across the square from the City Hall, where the American GIs handed out food stamps. Most of the people waited for their stamps in silence. Some argued. Ten years earlier, Hitler had promised to care for the German people, to give them food, shelter, and safety. He gave them ruin. Now the Western Allies—the Americans, British, and French—cared for the German people instead. The Allies called their effort “the reconstruction of Germany.” The reconstruction was mostly a humanitarian undertaking but also a strategic one. The Western Allies needed Germany to be the front for the Cold War against the Soviet Union. So the Americans, who occupied Southern Germany and Bavaria, decided to fix what was broken—in Germany’s interest, as well as their own.

Rather than traverse around the line of somber people, Franz wiggled through them. Some yelled at him, thinking he was trying to cut in front. Franz kept waddling through the masses. He noticed that the people’s eyes were drawn to his boots.

Franz’s jacket had moth holes—it had been his father’s. His green Bavarian britches had patches on the knees. But his boots were unusual. They covered his calves, and yellow mutton wool peaked over the tops. A silver zipper ran up the inside of each boot, and a black cross strap with a buckle spanned the front of the ankle.

His boots were the mark of a pilot. A year earlier, Franz had worn them proudly in the thin air six miles above earth. There he flew a Messerschmitt 109 fighter with a massive Daimler-Benz engine. When other men walked in the war, he flew at four hundred miles per hour. Franz had led three squadrons of pilots—about forty men—against formations of a thousand American bombers that stretched a hundred miles. In three years, Franz had entered combat 487 times and had been wounded twice, burned once, and somehow always came home. But now he had traded his black leather flying suit, his silk scarf, and his gray officer’s crush cap for the dirty, baggy clothes of a laborer. His pilot’s boots he kept—they were the only footwear he owned.

As he hurried along the street, Franz saw men and women crowded around the town message board to read its notes held by thumbtacks against the wind. There was no mail service and there were no phone lines anymore, so people turned to the board for word of lost family members. Some seven million people were now homeless in Germany. Franz saw a cluster of women standing behind the lift gate of an American Army truck. From inside the covered truck bed, gum-chewing GIs dropped duffels of laundry to the women while practicing sweet-talking in German. The women giggled and departed, each carrying two bags. They were headed for the old park north of the city where a branch of the Danube River curved along the town. There, the women would kneel on the banks and scrub the GIs’ laundry in the icy water. It was cold work but the Americans paid well.

The city’s main street ran north to the river. Franz turned, started down it, and encountered a new rush of humanity. He stopped in his tracks and gulped. He was too late. Every building on this block had a long line of men standing in front. They were all looking for work. Some men blew into their hands. Others twisted back and forth at the waist to stay warm. Most were veterans and wore the same gray tunics and long coats they had worn in the war. The thread outlines from patches they had torn away were still visible. Like Franz, they were competing for the scraps of a desolate economy.

The brickyard was farther down the street, and Franz hoped its line was shorter. He kept walking and passed people working in a bombed-out building, its wall open to the street. Under a canvas tarp, men in winter clothes huddled at their desks while repairing small motors. A woman missing an arm walked among them, delivering their work orders.

A honking horn warned Franz to jump to the curb as an American jeep, the Constabulary patrol, raced past—its GI riders wearing clean, white helmets. The Americans provided law and order while a small force of unarmed German police assisted with “local” matters. Some of the German veterans still looked away whenever the jeeps raced by.

Ahead, sitting on the bench where the buses used to stop, Franz saw the footless veteran. Every day the same man sat there in his tattered Army uniform. He looked forty years old but could have been twenty. His hair was long, his stubble gray, and his eyes blinked nervously as if he had seen a thousand hells. He was a vision of a bad past that everyone wanted to forget.

The footless veteran wobbled his mess kit in the air, looking for a handout. Franz fished in his pocket and dropped a food stamp into the man’s empty dish. Franz did this every time he saw the veteran, and he wondered if that was why the man always sat on the same bench. The veteran never said thanks or even smiled. He just gazed at Franz forlornly. For a moment, Franz was glad he had flown above the ground war. Six years of hand-to-hand fighting and months in Allied P.O.W. camps had left scores of veterans in the same predicament as the panhandler, listless and broken. But they were the lucky ones. The men captured by the Soviets were still missing.

Franz felt his lunch in his pocket—two slices of oat bread. He was not too proud to take handouts from the victors. Handouts meant eight hundred calories of food a day and survival. When Franz was a pilot, he had been well fed, a tradition begun in the First World War, when pilots were aristocrats who had to live well if they were to die painfully. In WWII, good food was considered a job perk, since no amount of money could convince a man to do what pilots did. During the war Franz had dined on champagne, cognac, crusty bread, sausages, cold milk, fresh cheese, fresh game, and all the chocolate and cigarettes he could handle. After the war, Franz had forgotten the feeling of being full.

A long line of workmen had already gathered at the brickyard. Franz groaned. The line wound down the length of the sidewalk from the destroyed building that had become the mill. These days, bricks didn’t have far to travel to be useful—only a block or two away—so the mill had sprung up in the middle of the city.

The men in the brickyard line were a rough mix of laborers. Baking bricks and distributing them was hard work. As Franz approached, they eyed his boots with silent judgment. Franz pretended not to notice. All he wanted was to work and blend in. He had been born an hour away, in tiny Amberg, Germany, where his girlfriend was now living with his mother. Franz had tried to fit in there after the war, but the people knew he had been a fighter pilot and blamed him for the country’s destruction. “You fighter pilots failed!” they had yelled at him. “You did not keep the bombs from falling!” So Franz decided to start over in Straubing, where he was a stranger. It was no use. The people of Straubing were as disenchanted with fighter pilots as everybody else in Germany. Once, fighter pilots had been the nation’s heroes. Now the hostile eyes of the men around Franz confirmed a new reality. Fighter pilots had become the nation’s villains. Franz turned from the glares of the men.

Two American GIs strolled down the street with German girls on their arms. In daylight, they could do this safely. At night they were liable to be attacked. The girls were cold and starving like everyone else, but they faced a choice: date a German man and go hungry, or date an American who could give them coffee, butter, cigarettes, and chocolate. Next to the boyish conquerors from the richest nation in the world, Franz and the German men in their work lines looked emasculated. “He fell for the fatherland, she for cigarettes,” the bitter German men would quip.

Finally the line moved forward, and Franz stood in front of a wooden folding table inside the brick mill. Behind the table sat the manager, a bald man with spectacles. Behind him, Franz saw workers packing red clay into molds and wheeling wheelbarrows of bricks. Franz handed his papers to the manager then looked at his boots, hoping the man had not yet noticed them. Franz’s papers listed: “1st Lieutenant, Pilot, Air Force.” Upon the war’s end, Franz had surrendered to the Americans, who were hunting for him because he was one of Germany’s top pilots who had flown the country’s latest aircraft. The Americans had wanted his knowledge. Franz had cooperated, and his captors had given him release papers that said that he was free to travel and to work. They had him released because his record was clean—he had never been a member of the National Socialist Party (the Nazis).

“So you were a pilot and an officer?” the manager asked.

“Yes, sir,” Franz said and looked at the floor.

“Bombers?” the manager asked.

“Fighters,” Franz said. He knew the man was baiting him, but Franz was not about to lie. The other workers in line began to whisper.

“So a fighter pilot wants to get his hands dirty now?” the manager said. “He wants to clean up the mess he caused?”

“Sir, I just want to work,” Franz said.

Gesturing to the ruined city around him, the manager recited the line Franz had heard countless times before. “You didn’t keep the bombs from falling!”

Biting his lip, Franz told the manager, “I just want to work.”

“Look elsewhere!” the manager said.

“I need this job,” Franz said. He leaned close to the manager. “I’ve got people to care for. I’ll work hard—harder than anyone else.”

The other men in line grumbled and crowded closer. “Move along,” yelled a voice from behind. Someone pushed Franz. “Stop holding up the line,” yelled someone else. They were angry for losing the war. They were angry at Hitler for misleading them. They were angry because another country now occupied theirs. But none of the men who surrounded Franz would admit this. They needed a scapegoat, and a fighter pilot stood right in front of them.

“Get out!” the manager hissed at Franz. “You Nazis have caused enough trouble.”

Nazi—the word made Franz’s eyes narrow with anger. “Nazi” was the new curse word the Germans had learned from the Americans. Franz was no Nazi. The Nazis were known to Franz as “The Party,” the National Socialists, power-hungry politicians and bureaucrats who had taken over Germany behind the fists of violent, disenchanted masses. They shouldn’t have ever been in charge. They’d only come to power after the elections of 1933, when twelve parties campaigned for seats in Germany’s parliament. Each party won a portion of the vote—there was no majority winner. In the end, the National Socialists won the most votes—44 percent of Germany had voted in their favor. This 44 percent gave the Nazis, and their leader, Adolf Hitler, enough seats in parliament to eventually seize dictatorial powers. Soon after, Hitler and his Nazis outlawed all future elections and all other political parties except for theirs, which became known as “The Party.” Hitler and The Party took over Germany after 56 percent of the country had voted against them.

Franz felt the blood beginning to boil behind his ears. He had been just seventeen, too young to vote in the 1933 election although his parents had voted against The Party. When Franz had come of age, he had never joined The Party. The Party had ruined his life. “I’m not a Nazi!” Franz told the manager. “All I want is to work.”

“Be a man and move along,” yelled someone from the line of men. Others jostled Franz. He felt the wind of angry breath on his neck.

“Get off my back!” Franz shouted to them, twisting his shoulders. Nothing bothered Franz more than someone standing too close behind him. It was his fighter pilot’s survival instinct to fear anyone or anything that approached from his back, his “six o’clock.” Franz knew if he turned around to face the angry men it would only start a fight, so he avoided eye contact with any in the crowd.

The manager picked up a phone mounted on the wall. Its line ran out the shattered window and into the street. He made a call, then told the other workers, “The police are coming.”

“Please don’t,” Franz said. “I’ve got a family to care for.”

The manager just sat back, his arms folded. Franz removed his cap, revealing a dent in his forehead where an American .50-caliber bullet had hit him in October 1944 after piercing his fighter’s armored windshield. Franz pointed to the dent and said, “Don’t rile me!”

The manager laughed. Franz fished inside his pocket and slapped a piece of paper on the table. It was a medical form from his former flight doctor, who had written that Franz’s head injury and its resulting brain trauma “could trigger adverse behavior.” In reality, Franz had not suffered brain damage, just a dented skull. The doctor had given him the slip as a sort of “get out of jail free” card for anything Franz said or did wrong.

The manager took the note, read it, and crumpled it up.

“An excuse for cowardice!” he told Franz.

“You have no idea what we did!” Franz said, clenching his fists. He had watched his fellow fighter pilots fight bravely until they died, one by one, while The Party’s leadership called them “cowards,” deflecting the blame for the destruction of Germany’s cities onto them. In reality, Franz and his fellow fighter pilots never stood a chance against the Allies’ industrial might and endless warplanes. Of the twenty-eight thousand German fighter pilots to see combat in WWII, only twelve hundred survived the war.

Franz leaned close to the man and whispered in his ear.1 Leaning back in his seat, the manager said, “Go ahead, try it.”

In one motion, Franz grabbed the manager by his collar, pulled him across the desk, and punched him between the eyes.

The manager stumbled backward into a cabinet. Other laborers seized Franz and slammed him to the floor. One kicked Franz in the ribs. Another punched him in a kidney. Together they ground his face into the dust-covered floor.

“You have no idea!” Franz shouted, his cheek pinned to the tiles.

THREE GERMAN POLICE officers arrived and blew their whistles to part the mob. The laborers lifted their knees from Franz’s back. The police hauled Franz up to his feet. The officers were strong and well fed by their American overseers. Franz wanted to run but could not escape.

With tears in his eyes, the manager told the police that Franz had demanded work ahead of the others and refused to leave. The angry mob confirmed the manager’s story.

Franz denied the accusations, but he knew a losing battle when he saw one. He was going to jail. But he needed to get his papers back. Franz told the officer in charge that the manager held them.

The officer motioned for the other police to take Franz away.

“Wait! He still has my medical form!” Franz objected. The manager handed over the note. The officer uncrumpled the waiver and read it to the other policemen: “. . . head wound, sustained in aerial combat.” The officer pocketed both of Franz’s papers and announced, “You’re still coming with us!”

Franz knew there was no point in resisting. The officers dragged him past the line of workers and into the street. A rush of fearful thoughts raced through Franz’s mind: How will I ever find work with an arrest record? What will I tell my girlfriend and mother? How will I provide for them?

Exhausted from struggling against the mob, hurting from the beating, and overwhelmed with grief, Franz fell limp as the police hauled him away. The toes of his heavy black flying boots dragged against the rough, upturned stones where bombs had fallen.

FOLLOW THE EAGLES

NINETEEN YEARS EARLIER, SUMMER 1927, SOUTHERN GERMANY

THE SMALL BOY sprinted through the open pasture, his feet in tiny brown shoes. He chased the soaring wooden glider as its pilot took off into the sky. The boy wore thick knit Bavarian kneesocks, green knickers, and a white shirt with short sleeves. He ran with arms outstretched. “Go! Go! Go!” he shouted as he waved the machine and its pilot onward. The glider resembled the skeleton of a dinosaur with a web of wires running within it. It flew one hundred feet above the pasture, and the sound of flapping fabric trailed in its wake. The boy followed the glider to the pasture’s edge and stopped when he could go no farther. He watched the contraption shrink into the distance over the rolling hills of Bavaria.

The glider soared with a whoosh over a farmer herding cows. An older boy flew the craft and sat in a wicker seat positioned over a ski that ran the glider’s length. There was no windshield or instrument panel and only straps across the young pilot’s shoulders secured him to the spartan craft. Minutes later, the pilot steered the machine in for a landing. He aimed for a worn white strip of grass in a green field where many landings had happened before. There, on a hill next to the landing strip, sat a short, wide shed where the youngsters and their adult advisors of the glider club were finishing a picnic. The small boy stood waiting at the shed. He held a short-brimmed tweed hat in his hands. The pilot coasted from one hundred feet to fifty feet to twenty-five feet and made a gentle three-bump landing. The pilot put his legs down to keep the glider from tipping over as the small boy ran up to the machine and darted under its wing. The boy was twelve-year-old Franz Stigler. The pilot was Franz’s sixteen-year-old brother, August.

Franz stood alongside the cockpit as August removed his white safety straps. August swung his legs to earth and carefully lowered the glider to rest on its wingtip. Franz handed the hat to August, who removed his goggles and flopped the hat onto his head like an ace after a dawn patrol. August was dressed like Franz, in kneesocks, knickers, and a white shirt with a tiny collar.

The brothers were true Bavarians; both had dark brown eyes, brown hair, and oval faces. August’s face was longer and calmer than Franz’s. August was straightlaced, a deep thinker, and often wore spectacles. Franz had youthful, chubby cheeks, and he was quiet, although quick to smile. August had been named “Gustel Stigler,” but he preferred “August.” Franz had been named “Ludwig Franz Stigler,” but went by “Franz,” which irked the boys’ strong, proper, deeply Catholic mother. Their father was easygoing and allowed the boys to call themselves whatever they wanted.

Franz praised August’s flight, rehashing what he had seen as if August had not been there. August told Franz he was glad he had paid attention because it would be Franz’s turn next. The other eight boys of the glider club converged around the brothers and helped carry the glider up the nearby hill to the flat launch point on top. August was the oldest of the boys and their leader.2 Some of the boys were as young as nine and were not yet allowed to fly. But on this day, Franz—age twelve—was scheduled to become their youngest pilot.

Two adults in the glider club followed the boys up the hill. The men hauled a heavy, black rubber rope used to launch the glider. One of the adults was Franz’s father, also named Franz. He was a thin man with a tiny mustache and circular spectacles that looped over big ears. He hugged August then helped Franz strap into the glider’s thin, basket-like seat. The other adult was Father Josef, a Catholic priest and the boys’ teacher, who handled fifth through eighth grades at their Catholic boarding school. Father Josef was in his fifties and had gray hair around the sides of his head. His face was strong, and his eyes were blue and friendly. When Father Josef was gliding, he traded his black robe and flat-brimmed hat for a white shirt and mountaineering pants. A large wooden cross dangled from his neck. Father Josef walked around the glider, checking its surfaces. Both men had flown for the German Air Force in WWI. Franz’s father had been a reconnaissance pilot. Father Josef had been a fighter pilot.

Both adults had a habit of downplaying their service in the war. From the bird’s-eye perspective of pilots, they had seen the stacks of muddy corpses between the battle lines. When Germany lost the first war, the two men lost their jobs. In the Treaty of Versailles, the victorious French, British, and Americans stipulated that the German Air Force was to dissolve and the Army and Navy were to disarm. Germany also needed to hand over its overseas colonies, allow foreign troops to occupy its western borderlands, and pay 132 billion Deutsche Marks in damages (about $400 billion today). As they paid the price for the war they’d lost, Germany fell into a deep economic depression long before the great global financial collapse of 1929.

Franz’s father and Father Josef had started the glider club to teach boys to enjoy the only good thing the war had taught them—how to fly. When the men had started the club, neither had enough money to buy a glider for the boys. Franz’s father managed horses at a nearby estate. Father Josef had left the military for the priesthood. They told the boys that if they wanted to learn to fly, they would have to build a glider themselves. After school each day for months, August, Franz, and the other boys collected scrap metal and sold it to buy the blueprints for a Stamer Lippisch “Pupil” training glider. Father Josef wrangled a woodshed for them, high on a hill west of Amberg, the ancient, ornate Bavarian town they all called home. There in the shed, on weekends and holidays, the boys began building the glider. Stacks of wood and fabric came first. Blueprints in hand, it took a year for them to build the glider. Safety inspections followed. Administrators from the Department of Transport would not let the boys ride without first checking out the craft. The verdict came back. The boys had done well and were cleared for takeoff.

High on top of the hill, Franz tugged the canvas straps that held his shoulders to the glider’s seat. Two other boys held each wingtip to keep the glider from tilting over. Franz’s father attached the rubber rope to a hook in the glider’s nose, next to where the landing ski curved upward. Father Josef and the other boys took hold of both ends of the rope, three per side. August knelt next to Franz. With a hand on his shoulder, he offered Franz some parting wisdom, “Stay below thirty feet and don’t try to turn. Just get the feel of flying, then land.” Franz nodded, too scared to speak. August took his place on the rope line. Franz’s father reminded him, “Land before you reach the end of the field.” Franz nodded again.

Franz’s father sat on the ground and held the glider’s tail. He was the biggest man and acted as the anchor. He shouted for Father Josef and the others to pull the rope taut. They began to walk down the hill, spreading the rope into a V with the glider at the center, the slack tightening, the rope quivering.

Franz lifted his feet from the ground and extended his tiny legs to the rudder stick. He gripped the wooden control stick that jutted up from a box on the ski between his thighs. The control stick was attached to wires that extended to the wings and tail to make the glider maneuver.

Father Josef and the boys gripped the rope with all their might, pulling out all slack. The cord trembled with energy. “Okay, Franz,” Father Josef shouted up to him. “We launch on three!” Franz gave a wave. His heart pounded. Father Josef led the count, “One! Two! Three!” Everyone on the rope sprinted down the hill. The rope stretched with elastic energy, and Franz’s father released the tail.

Franz rocketed forward—then instantly straight up. Something was seriously wrong. Instead of a gradual, level takeoff, the glider blasted upward like a missile, carrying its sixty-pound passenger toward the sun.

“Push!” Franz’s father screamed. “Push forward!”

Franz jammed the control stick forward. The glider leveled off, nosed downward, then plunged. Frozen with fear, Franz flew straight toward the ground. Crack! The glider’s nose plowed into the dirt. The machine tipped over, its wings thudding into the grass above Franz’s head.

Franz’s father, brother, and Father Josef sprinted to the glider. The other boys stood in shock. They were certain that Franz was dead. All they could see was the tops of the wings and the tail jutting into the air.

The two men lifted the machine by the wing and Franz flopped backward, still tied to his seat. He was mumbling and groggy. August unstrapped him and pulled Franz’s limp body out of the glider. Slowly, Franz opened his eyes. He was stunned but unhurt. Franz’s father clutched his son, hugging and crying at the same time.

“It’s my fault, not yours,” Franz’s father said.

Turning to Father Josef, Franz’s father said, “The glider was designed for a heavier passenger—we forgot to compensate.” Father Josef nodded in agreement. After a few minutes, Franz walked wobbly from the wreck with August holding him up. He had made his first flight and first crash all at once. “I thought you did pretty well,” August told Franz with a grin. “At least you stayed under thirty feet and didn’t try to turn!”

THE GLIDER COULD be rebuilt, so the boys worked on it, just as they had built it. Every weekend they would drag the glider’s wing from the barn and replace its broken spars over sawhorses in the grass. Franz’s task was to re-glue the wing ribs, while the older boys did more precise jobs, like cutting new ribs and fitting them. Franz brushed the glue over the wood’s seams heavily, thinking that he would not miss a spot if he coated everything. Franz’s father dropped in now and then to inspect their progress. When he came to Franz’s work, he looked long and hard at the globs of glue piling up along each seam. Franz stood a few paces back, proudly.

“It’s a little sloppy, don’t you think?” Franz’s father observed.

“I didn’t miss a spot,” Franz promised.

“There’s glue in places that didn’t need it,” Franz’s father elaborated.

“It doesn’t bother me,” Franz said, “the fabric will cover it.”

Franz’s father gave him a lesson. “Always do the right thing, even if no one sees it.”

Franz admitted it was sloppy, but he promised, “No one will know it’s there.”

“Fix it,” his father advised, “because you’ll know it’s there.”

That day and in the many that followed, when the other boys took breaks from their work to kick the soccer ball, Franz kept working. He wore his fingers bloody by shaving the excess glue with sandpaper. He smoothed the seams of each of the twenty-odd ribs, perfectly. When the boys rewrapped the wings with fabric then coated the fabric with lacquer that would forever seal the glider’s skeleton, no one noticed Franz’s meticulous work—except for his father and him.

Several months later, Franz shot into the skies with a sandbag tied to his waist. This time he soared, one hundred feet above Bavaria. August ran below, waving Franz onward. Franz saw his craft’s wings flex and bend with the turbulence. He could see the curving Danube River to the east. Turning to the south, he could see the foothills of the Alps. Turning west, he saw a swath of forest looming ahead, so he turned hard to avoid it. The air did not rise over a forest or river, every glider pilot knew—you steered for fields and hills where the updrafts lifted your wings. Franz felt the rising air currents and saw birds above him, spiraling upward. August had told him, “The eagles know where the good air is—follow them.”

A FEATHER IN THE WIND

FIVE YEARS LATER, FALL 1932, NEAR AMBERG

FRANZ WAITED ON the stone bench. It was just after the midday meal, and the tall walls of his Catholic boarding school loomed around him. Leafy trees above the walls cast thicker shadows. Monks in their brown robes darted along the corridors. Franz wore his school uniform, but his gray pants were grass-stained and his white shirt sullied and rumpled. Franz was now seventeen. The baby fat had melted from his cheeks, revealing a lean, strong jaw. One ear looked inflamed and red.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!