Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

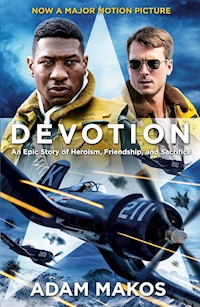

***NOW A MAJOR FILM, STARRING JONATHAN MAJORS AND GLEN POWELL*** 'This is aerial drama at its best. Fast, powerful, and moving.'Erik Larson 'A must read.' New York Post Devotion is the gripping story of the US Navy's most famous aviator duo - Tom Hudner, a white, blue-blooded New Englander, and Jesse Brown, a black sharecropper's son from Mississippi. Against all odds, Jesse beat back racism to become the Navy's first black aviator. Against all expectations, Tom passed up a free ride at Harvard to fly fighter planes for his country. Barely a year after President Truman ordered the desegregation of the military, the two became wingmen in Fighter Squadron 32 and went on to fight side-by-side in the Korean War. In an enthralling narrative, Adam Makos follows Tom and Jesse's journey to the war's climatic battle at the Chosin Reservoir, where they flew headlong into waves of troops in order to defend an entire division of Marines trapped on a frozen lake. It was here that one of them was faced with an unthinkable choice - and discovered how far they would go to save a friend.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 625

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To the veterans of the forgotten victory in Korea, 1950–1953

CONTENTS

Introduction 1. Ghosts and Shadows2. The Lesson of a Lifetime3. Swimming with Snakes4. The Words5. The Renaissance Man6. This Is Flying7. So Far, So Fast8. The Ring9. The Pond10. One for the Vultures11. A Time for Faith12. A Deadly Business13. A Knock in the Night14. The Dancing Fleet15. The Reunion16. Only in France17. The Friendly Invasion18. At First Sight19. On Waves to War20. The Longest Step21. The Last Night in America22. The Beast in the Gorge23. Into the Fog24. This Is It25. Trust26. He Might Be a Flyer27. Home28. The First Battle of World War III29. The Sky Will Be Black30. A Chill in the Night31. A Taste of the Dirt32. When the Deer Come Running33. Backs to the Wall34. A Smoke in the Cold35. The Lost Legion36. Burning the Woods37. Into Hell Together38. All the Faith in the World39. Finality40. With Deep Regret41. To the Finish42. The Gift43. The Call from the Capital44. The Message Afterword Acknowledgments Bibliography Notes Photo Credits IllustrationsINTRODUCTION

FROM ACROSS THE HOTEL LOBBY, I saw him sitting alone, newspaper in hand.

He was a distinguished-looking older gentleman. His gray hair was swept back, his face sharp and handsome. He wore a navy blazer and tan slacks, and his luggage sat by his side.

The lobby was buzzing, but no one paid him any special attention. It was fall 2007, another busy morning in Washington, D.C. I was twenty-six at the time and trying to make it as a writer for a history magazine. I had a book under way on the side but no publisher yet in sight. The book was about my one and only specialty—World War II.

The day before, I had heard the distinguished gentleman speak at a veterans’ history conference. I had caught part of his story. He was a former navy fighter pilot who had done something incredible in a war long ago, something so superhuman that the captain of his aircraft carrier stated: “There has been no finer act of unselfish heroism in military history.”

President Harry Truman had agreed and invited this pilot to the White House. Life magazine ran a story about him. His deeds appeared in a movie called The Hunters, starring Robert Mitchum. And now here he was—sitting across the lobby from me.

I wanted to ask him for an interview but hesitated. A journalist should know his subject matter and I was unprepared.

He had flown a WWII Corsair fighter, I understood that much. Reportedly he had fought alongside WWII veterans and fired the same bullets and dropped the same bombs used in WWII. He was a member of the Greatest Generation, too.

But he hadn’t fought in World War II.

He had fought in the Korean War.

To me, the Korean War was a mystery. It is to most Americans; our history books label it “The Forgotten War.” When we think of Korea, we picture M*A*S*H or Marilyn Monroe singing for the troops or a flashback from Mad Men.

Only later would I discover that the Korean War was practically an extension of World War II, fought just five years later between nations that had once called themselves allies. Only later did I discover a surprising reality: The Greatest Generation actually fought two wars.

The gentleman was folding his newspaper to leave. It was now or never.

I mustered the nerve to introduce myself and we shook hands. We made small talk about the conference and finally I asked the gentleman if I could interview him sometime for a magazine story. I held my breath. Maybe he was tired of interviews? Maybe I was too young to be taken seriously?

“Why, sure,” he said robustly. He fished a business card from his pocket and handed it to me. Only later would I realize what an opportunity he’d given me. His name was Captain Tom Hudner. And that’s how Devotion began.

True to his word, Tom Hudner granted me that interview. Then another, and another, until what began as a magazine story blossomed into this book. And the book kept growing. I discovered that Tom and his squadron weren’t your typical fighter pilots—they were specialists in ground attack, trained to deliver air support to Marines in battle. So what began as the story of fighter pilots became a bigger story, an interwoven account of flyboys in the air, Marines on the ground, and the heroes behind the scenes—the wives and families on the home front.

Over the ensuing seven years, from 2007 to 2014, my staff and I interviewed Tom and the other real-life “characters” of his story more times than we could count. All told, we interviewed more than sixty members of the Greatest Generation—former navy carrier pilots, Marines, their wives, their siblings. This story is set in 1950, so many of the people we interviewed were still young for their generation. They were in their seventies and early eighties, with sharp, vibrant memories.

At times, I stepped away from Devotion to work on my World War II book while my staff kept plugging away on Devotion. They had help, too. The historians at the navy archives, the Marine Corps archives, and the National Archives were practically on call to aid our research.

Over those seven years we worked as a team—the book’s subjects, the historians, my staff, and I—to piece together this story. Our goal was for you not just to read Devotion but to experience it. To construct a narrative of rich detail, we needed to zoom in close. Our questions for the subjects were countless. When a man encountered something good or bad, what did he think? What facial gestures corresponded with his feelings—did his eyes lift with hope? Did his face sink with sorrow? What actions did he take next?

More than anything, we asked: “What did you say?” I love dialogue. There’s no more powerful means to tell a story, but an author of a nonfiction book can’t just make up what he wants a character to say. This is a true story, after all, so I relied on the dialogue recorded in the past and the memories of our subjects, who were there.

Time and again we asked these “witnesses to history” to reach into their pasts and recall what they had said and what they had heard others say. In this manner, we re-created this book’s dialogue, scene by scene, moment by moment. In the end, before anything went to press, our principal witnesses to history read the manuscript and gave their approval.

I owe a debt of gratitude to these real-life “characters” of Devotion, people you’ll soon meet and never forget—Tom, Fletcher, Lura, Daisy, Marty, Koenig, Red, Coderre, Wilkie, and so many others. Devotion was crafted by their memories as much as it was written by me.

There was another level of research that this book required. I needed to see the book’s settings for myself—all of them, from New England to North Korea. So I hit the road and followed the characters’ footsteps to the places where they grew up, flew, and fought.

That journey led me from Massachusetts to Mississippi, to the French Riviera and Monaco, to a port in Italy, a ship off the coast of Sicily, and back to the battlefields of the Korean War. I had been to South Korea before on a U.S.O. tour, but never to that shadowy land to the north—North Korea.

But before the book was done, my staff and I went there too. We traveled to China and then into that misty place known as “the hermit kingdom,” the land where some Americans enter and later fail to reemerge. Our trip to North Korea is a story in itself, but let’s just say I owe its success to Tom Hudner.

As Devotion neared completion, I struggled for a way to describe this interwoven story to you, the reader. My prior book—A Higher Call—had been easy to categorize. It was the true story of a German fighter pilot who spared a defenseless American bomber crew during WWII.

It was a war story.

Devotion is a war story, too.

But it differs in that it’s also a love story. It’s the tale of a mother raising her son to escape a life of poverty and of a newlywed couple being torn apart by war.

It’s also an inspirational story of an unlikely friendship. It’s the tale of a white pilot from the country clubs of New England and a black pilot from a southern sharecropper’s shack forming a deep friendship in an era of racial hatred.

As I was editing the last pages of this manuscript, the answer hit me. I knew how to categorize Devotion.

The bravery. The love. The inspiration.

This is an American story.

DEVOTION

CHAPTER 1

GHOSTS AND SHADOWS

December 4, 1950

North Korea, during the first year of the Korean War

IN A BLACK-BLUE FLASH, a Corsair fighter burst around the valley’s edge, turning hard, just above the snow. The engine snarled. The canopy glimmered. A bomb hung from the plane’s belly and rockets from its wings.

Another roar shook the valley and the next Corsair blasted around the edge. Then came a third, a fourth, a fifth, and more until ten planes had fallen in line.

The Corsairs dropped low over a snow-packed road and followed it across the valley, between snow-capped hills and strands of dead trees. The land was enemy territory, the planes were behind the lines.

From the cockpit of the fourth Corsair, Lieutenant Tom Hudner reached forward to a bank of switches above the instrument panel. With a flick, he armed his eight rockets.

Tom was twenty-six and a navy carrier pilot. His white helmet and raised goggles framed the face of a movie star—flat eyebrows over iceblue eyes, a chiseled nose, and a cleft chin. He dressed the part too, in a dark brown leather jacket with a reddish fur collar. But Tom could never cut it as a star of the silver screen—his eyes were far too humble.

An F4U Corsair

At 250 miles per hour, Tom chased the plane ahead of him. It was nearly 3 P.M., and dark snow clouds draped the sky with cracks of sun slanting through. Tom glanced from side to side and checked his wingtips as the treetops whipped by. Beyond the hills to the right lay a frozen man-made lake called the Chosin Reservoir. The flight was following the road up the reservoir’s western side.

The radio crackled and Tom’s eyes perked up. “This is Iroquois Flight 13,” the flight leader announced from the front. “All quiet, so far.”

“Copy that, Iroquois Flight,” replied a tired voice. Seven miles away, at the foot of the reservoir, a Marine air controller was shivering in his tent at a ramshackle American base. His maps revealed a dire situation around him. Red lines encircled the base—red enemy lines. To top it off, it was one of the coldest winters on record. And the war was still new.

* * *

The engine droned, filling Tom’s cockpit with the smell of warm oil. Tom edged forward in his seat and looked past the whirling propeller. His eyes settled on the Corsair in front of him.

In the plane ahead, a pilot with deep brown skin peered through the rings of his gunsight. The man’s face was slender beneath his helmet, his eyebrows angled over honest dark eyes. Just twenty-four, Ensign Jesse Brown was the first African American carrier pilot in the U.S. Navy. Jesse had more flight time than Tom, so in the air, he led.

Jesse dipped his right wing for a better view of the neighboring trees. Tom’s gut tensed.

“See something, Jesse?” Tom radioed.

Jesse snapped his plane level again. “Not a thing.”

Through the canopy’s scratched Plexiglas, Tom watched the cold strands blur past at eye level. The enemy was undoubtedly there, tucked behind trees, grasping rifles, holding their fire so the planes would pass.

Tom clenched his jaw and focused his eyes forward. As tempting as it was, the pilots couldn’t strafe a grove of trees on a hunch. They needed to spot the enemy first.

The enemy were the White Jackets, Communist troops who hid by day and attacked by night. For the previous week, their human waves had lapped against the American base night after night, nearly overrunning the defenses. Nearly a hundred thousand White Jackets were now laying siege to the base and more were arriving and moving into position.

Against this foe stood the base’s ten thousand men—some U.S. Army soldiers, some British Commandos, but mostly U.S. Marines. Reportedly, the base even had its cooks, drivers, and clerks manning the battle lines at night, freezing alongside the riflemen.

Their survival now hinged on air power and the Corsair pilots knew it. Every White Jacket they could neutralize now would be one fewer trying to bayonet a young Marine that night.

“Heads up, disturbances ahead!” the flight leader radioed.

Finally, something, Tom thought.

Tom’s eyes narrowed. Small boulders dotted the snow beside the road.

“Watch the rocks!” Jesse said as he zipped over them.

“Roger,” Tom replied.

Tom wrapped his index finger over the trigger of the control stick. His eyes locked on the roadside boulders.

When caught in the open, White Jackets would sometimes drop to the ground and curl over their knees. From above, their soiled uniforms looked like stone and the side flaps of their caps hid their faces.

The rock pile slipped behind Tom’s wings. He glanced into his rear-view mirror. Behind his tail flew a string of six Corsairs with whirling, yellow-tipped propellers. If any rocks stood now to take a shot, Tom’s buddies would deal with them. Tom trusted the men behind him, just as Jesse entrusted his life to Tom.

After two months of flying combat together, Tom and Jesse were as close as brothers, although they hailed from different worlds. A sharecropper’s son, Jesse had grown up dirt-poor, farming the fields of Mississippi, whereas Tom had spent his summers boating at a country club in Massachusetts as an heir to a chain of grocery stores. In 1950 their friendship was genuine, just ahead of the times.

Tom caught the green blur of a vehicle beneath his left wing. Then another on the right.

He leaned from side to side for a better view.

Abandoned American trucks and jeeps lined the roadsides. Some sat on flat tires and others nosed into ditches. Snow draped the vehicles; their ripped canvas tops flapped in the wind. Cannons jutted here and there, their barrels wrapped in ice.

Tom’s eyes narrowed. Splashes of pink colored the surrounding snow. “Oh Lord,” he muttered. The day before, the Marines had been attacked here as they fought their way back to the base. In subzero conditions, spilled blood turned pink.

“Bodies, nine o’clock!” the flight leader announced as he flew past a hill on the left. “God, they’re everywhere!”

Jesse zipped by in silence. Tom nudged his control stick to the left and his fifteen-thousand-pound fighter dipped a wing.

Sun warmed the hillside, revealing bodies stacked like sandbags across the slope. Mounds of dead men poked from the snow, their frozen blue arms reaching defiantly. Tom’s eyes tracked the carnage as he flew past.

Are they ours or theirs? he wondered.

Just the day before, he had flown over and seen the Marines down there, waving up at him, their teenage faces pale and waxy. He had heard rumors of the horrors they faced after nightfall. That’s when the temperature dropped to twenty below, when the enemy charged in waves, when the Americans’ weapons froze and they fought with bayonets and fists.

Aboard the aircraft carrier, Tom and the other pilots had become accustomed to starting each morning with the same question: “Did our boys survive the night?”

With a deep growl, the flight—now just six Corsairs—burst into a new valley northwest of the reservoir.

Frustration lined Tom’s face. The enemy had remained elusive so the flight leader had dispatched the rearmost four Corsairs to search elsewhere.

The remaining six planes followed the road farther into hostile territory. The clouds ahead became stormier, as if the road were luring the pilots into Siberia itself.

Tom scanned for signs of life as the flight raced between frozen fields. Snow-covered haystacks slipped past his wings. Crumbling shacks. Trees swaying in the wind.

“Possible footprints!” Jesse announced. Tom glanced eagerly forward.

“Nope, just shadows,” Jesse muttered as he flew overhead.

Tom could tell that Jesse was frustrated too. They both should have been far from this winter wasteland. Tom should have been sipping a scotch in a warm country club back home and Jesse should have been bouncing his baby daughter on his lap under a Mississippi sun. Instead, they’d both come here as volunteers.

It wasn’t the risk that bothered them—they were frustrated because they wanted to do something, anything, to defend the boys at the base. The night before, Jesse had written to his wife, Daisy, from the carrier: “Knowing that he’s helping those poor guys on the ground, I think every pilot on here would fly until he dropped in his tracks.”

Ahead of the flight, a voice barked a command from a roadside field. A dozen or more rifles and submachine guns rose up from the snow. Numb fingers gripped the weapons and shaking arms aimed skyward—arms wrapped in white quilted uniforms.

The White Jackets. They had heard the planes coming and taken cover.

The shadow of the first Corsair passed overhead—yet the enemy troops held their fire. The second shadow zipped safely past, too. The shadow of Jesse’s Corsair next raced toward the spot where weapons stood like garden stakes.

As Jesse’s shadow stretched over the hidden soldiers, the voice shouted. The rifles and submachine guns fired a volley, sending bullets rocketing upward. Quickly, the weapons lowered back into the snow.

The shadow of Tom’s plane flew over the enemy next, then two more Corsair shadows in quick succession. Over the roar of their 2,250-horsepower engines, none of the pilots heard the gunshots. One would later remember seeing the disturbance in the snow, but at 250 miles per hour, no one saw the enemy.

Rather than patrol another desolate valley, the flight leader climbed into an orbit over the surrounding mountains and ordered the flight to re-form.

Tom pulled alongside Jesse’s right wing and together they climbed toward the others.

“This is Iroquois Flight 13,” the leader radioed the base. “Road recon came up dry. Got anything else?”

“Copy,” the Marine controller replied. “Let me check.”

Tom and Jesse tucked in behind the leader and his wingman. The trailing two Corsairs slipped in behind them. From the rear of the formation, a pilot named Koenig radioed with alarm. “Jesse, something’s wrong—looks like you’re bleeding fuel!”

Jesse squirmed in his seat to see behind his tail, but his range of vision ended at his seatback. He looked to Tom across the cold space between their planes.

Tom glanced leftward and saw a white vapor trail slipping from Jesse’s belly. “You’ve got a streamer, all right,” Tom said.

Jesse nodded.

“Check your fuel transfer,” Koenig suggested. Sometimes fuel overflowed while being transferred from the plane’s belly tank to its internal tank.

Jesse glanced at the fuel selector switch above his left thigh. The handle was locked properly, so that wasn’t the problem. He studied the instrument panel. The needle in the oil pressure gauge was dropping.

Jesse glanced at Tom with a furrowed brow. “I’ve got an oil leak,” he announced.

Tom’s face sank. The hole in Jesse’s oil tank was a mortal wound. With every passing second, the oil was draining, the friction was rising, and the plane’s eighteen pistons were melting in their cylinders.

“Losing power,” Jesse said flatly.

“Can you make it south?” Tom asked.

“Nope, my engine’s seizing up,” Jesse said. “I’m going down.”

How is he so calm? Tom thought. Jesse’s propeller sputtered and his plane pitched forward into a rapid descent. Instinctively, Tom held formation and followed him down. Jesse was too low to bail out, so Tom frantically scanned the terrain for a suitable crash site. All he saw were snowy mountains and valleys studded with dead trees. This can’t be happening, Tom thought. Jesse would never survive a crash in this terrain and if he did, the subzero cold would kill him.

Tom glanced down to his kneeboard map and his face twisted. Jesse was going down seventeen miles behind enemy lines. If he survived the crash, the enemy would surely double-time it to capture him, and if they didn’t shoot him on sight, they had an unspeakable torture that they used on captured pilots.

Tom glanced over at Jesse as their Corsairs plummeted toward the mountains. Jesse’s eyes were fixed forward as he tried to sort through a hopeless hand of fate.

Tom needed to do something to help his friend, and fast.

Jesse’s story couldn’t end like this.

CHAPTER 2

THE LESSON OF A LIFETIME

Twelve years earlier, spring 1938

Fall River, Massachusetts

THE CAFETERIA OF MORTON JUNIOR HIGH buzzed with chattering young voices. Boys and girls waited in lunch lines while other students sat at long tables and ate from tin lunch pails. The green linoleum floor reflected more than two hundred conversations and the noise bounced up to a white ceiling made of textured plaster drippings.

Thirteen-year-old Tom Hudner set his tray on a table and sat next to his friends, all boys in the eighth grade, just like him. He wore a white polo shirt and khakis. His chin was strong, and his eyes were blue and honest. Even as young teenagers, Tom and the other boys still sat away from the girls. Morton Junior High was a place of rules and playground codes, and to sit with the opposite gender would invite ridicule. Tom was a rule follower by nature.

He unfolded a paper napkin, popped the cap on his bottle of milk, and began to eat. Tom bought a hot lunch every day for thirty-five cents, a perk of having affluent parents. He chewed silently and listened far more than he spoke. During a lull in the conversation, Tom’s gaze shifted. Outside the cafeteria’s windows, the school’s bullies were gathering in a corner of the courtyard where kids played after lunch.

Tom Hudner

They were the immigrant kids, dark-skinned sons of the Portuguese fishermen who had settled in Fall River. Tom placed his napkin on the table and stood up to get a better view. The tough Portuguese kids were tossing around a pair of eyeglasses, each boy trying them on and laughing. At the center of the circle, Tom could see a boy haplessly lunging to snatch his glasses back. The boy was overweight and wore his hair slicked to one side. Tom recognized him as Jack. Kids often ridiculed Jack for being quick to cry but Tom was friends with him, and most everyone for that matter.

Tom alerted the boys around him: “Someone should tell the teacher.” He looked around, but the teacher was nowhere to be seen. Outside, Jack was turning red and about to cry. The boys around Tom scowled, not because of their affection for Jack.

“Portugee rats!” one said.

“Dirty boat hoppers,” whispered another. “They should go back to where they came from.”

Tom didn’t know the Portuguese kids personally, but they seemed like trouble. The schoolchildren even had a name for the dirty industrial borough near the waterfront that the immigrants called home: “Portugee-ville.”

“We should do something,” Tom blurted.

Nobody moved.

One of Tom’s friends shrugged and looked away. “I’m not getting mixed up in this,” he muttered.

“Yeah, I barely know Jack, anyhow,” said another.

One by one, Tom’s friends sat down. Only Tom remained standing. Outside, he saw that Jack was now blubbering like a baby.

“Come on, guys,” Tom pleaded.

“He’s your friend, not ours,” a boy said.

“If you feel so bad for him, you should do something about it!” another added.

“Okay, fine,” Tom said. He sighed and walked toward the door.

Tom stepped out into the pale afternoon sunlight and approached the bullies. “Hey, fellas,” Tom said. The Portuguese kids stopped laughing at Jack and turned, some grinning, some glaring. Tom’s stride slowed. His mind raced to think.

“You say something?” called one of the bullies.

Tom stopped and tried to smile. “I don’t think Jack’s enjoying this very much,” he said. It was the only thing that came to mind.

One of the bullies emerged from the group and sauntered closer. The teen was short and stocky with an aggressive face and brooding eyes. Tom recognized him as Manny Cabral, the gang’s leader. Manny’s brown slacks were patched, and his dark T-shirt had a stretched-out neck. He walked over and stood with his nose nearly touching Tom’s.

“I think you should stay out of our business,” Manny said.

“C’mon, he’s crying,” Tom said quietly. Out of the corner of his eye, he saw Jack running away, fumbling with his glasses.

“We were only having fun,” Manny said, gesturing to his buddies. When he looked back at Tom, his voice lowered. “So what are you going to do about it?”

Tom’s heart pounded. He had never been in a fight but felt Manny was suggesting it. He wanted to tell Manny to let bygones be bygones, but Manny spoke first.

“We’ll settle the matter later,” he said casually. His eyebrow lifted, seemingly with a change of heart. “After school, outside.”

Tom gulped.

“You gonna show?” Manny asked.

Tom’s eyes darted from Manny to his gang to the circle of students that had gathered to watch the spectacle.

Just say no, Tom thought. But he knew that wasn’t an option. If Tom said no, the gang would never leave him alone. An all-American boy in 1938 had no option except to agree.

“Okay, I’ll be there,” Tom said.

Manny smiled and walked away. His gang followed, all laughing and talking loudly. Tom plodded back toward the cafeteria. His friends’ faces were pressed against the window glass.

Tom and his friends returned to their table. The others congratulated Tom for putting Manny Cabral in his place.

Tom looked down at his cold food and shook his head. “I’ve got to fight Manny after school.” Just saying the words made him lightheaded. Tom’s friends assured him not to worry; they would back him up.

Tom thought of his father, Thomas Hudner Sr., and how he would react. His father ran a chain of eight grocery stores called Hudner’s Markets and always said that the Portuguese immigrants were some of his best workers, people committed to building a new future for themselves. Senior wouldn’t be happy about his son getting in a fight—that much was for sure. But Tom remembered something else his father had told him: Always assume the best of people. But if a guy proves he’s no good, then don’t hesitate to give him what he deserves.

* * *

When the bell rang at the day’s end, Tom’s buddies surrounded him in the hallway. They slapped his back as if he were a football player about to take the field. Tom closed his locker and walked out the double doors. Tom’s buddies followed him, along with a few supporters.

Fifty yards away stood the white flagpole and a large cluster of students. At the center of the crowd stood the surly-looking Portuguese kids and Manny Cabral. Tom’s heart began to race.

He glanced over his shoulder for his friends but they had disappeared. He scanned the crowd and saw that all eyes were on him. Then Tom spotted his friends. They were clear across the street, huddled up, watching and whispering.

Tom was alone.

He stopped, set down his books, and took off his jacket to keep it clean. The crowd murmured. Tom stepped toward Manny Cabral and the crowd hushed. Manny glared blankly as the kids closed the circle behind Tom. Tom raised his fists and turned his palms inward, thinking of pictures he’d seen of boxers. His fists trembled.

“Whip him, Manny!” yelled a Portuguese kid.

“Yeah, beat him good!” urged another.

Tom noticed the strangest thing—despite the presence of his supporters, no one was cheering for him. They were too afraid.

Manny stepped forward and raised his fists like a professional fighter. He dropped his chin and scrunched his face, eyebrows dropping low.

Tom’s feet felt light, as if his soul had floated out of his body. Every face in the crowd seemed blurred except Manny’s. All of the voices faded. Tom could hear only the blood pumping in his ears. With his fists up and shaking, he began bouncing on his feet—the way he’d seen in the movies. Manny stood stock-still, fists poised to strike.

“Slug him, Manny!” someone yelled. Manny bobbed lightly, as if he was waiting for the perfect moment. Tom was too terrified to throw the first punch. His fists shook. He kept doing all he knew—shuffling his feet.

Manny raised an eyebrow. His expression loosened, he raised his chin and dropped his fists. His fingers uncurled.

Tom stopped bobbing. He kept up his guard.

Manny stepped toward Tom and thrust forward his right hand. His palm was open.

Tom lowered his fists and looked down at Manny’s outstretched hand, confused.

“Go ahead, shake,” Manny said.

The crowd grew silent. Tom unclenched his fists. He reached out his trembling hand and took Manny’s hand in his. They shook up then down just once.

Manny turned to his gang. “He’s okay,” he said. “It’s all right between us.” Then he turned and walked away. His gang lingered, speechless, then followed him down the street, toward the docks.

Tom watched the students disperse until he found himself alone by the flagpole. Across the street, his friends had disappeared. Tom gathered his books and jacket and began to walk home. His adrenaline was racing, and he soon began to jog, then run. He ran up Highland Avenue toward his home on the hill. He passed North Park, with its hills and Victorian mansions on the fringes.

At the top of the hill, Tom hung a right and saw his home, a three-story Victorian with gray wooden shingles and tall windows. The Hudner family had prospered even during the Great Depression because the grocery industry was always in demand. Tom’s face tightened as he ran up to the porch and entered his home.

Inside, Tom untied his polished Oxford shoes and placed them on a doormat. His mother was away, probably playing bridge, and his father was still at work.

In the back of the house, Tom heard the maid, Mary Getchell, stirring in the kitchen, preparing dinner. She was their housekeeper, thin, gray-haired, and Irish by descent, like the Hudners. The children called her “Nursey.”

Tom snuck up the staircase, past his father’s pennants from Andover prep school and Harvard University. On the second floor, where his parents and younger brothers and sister had their bedrooms, Tom turned the corner and kept going. He followed another staircase to the third floor, where his room lay opposite Nursey’s. Inside, the ceiling of Tom’s room was sharply angled and a rectangular window overlooked the street in front of the house. A crucifix hung next to the doorway and a Boy Scout poster hung on the wall. A baseball glove sat perched on his bedpost.

Tom tossed his books on his desk and flopped onto the bed. A model of an old schooner sat on his dresser along with a copy of his favorite book, Beat to Quarters, the tale of a British sea captain named Horatio Hornblower. Comic books littered Tom’s nightstand, their covers filled with colorful scenes of pirates and sea monsters. Tom loved ships. His favorite movie was Mutiny on the Bounty, and at the country club’s summer camp his favorite activity was sailing.

As he lay on his sheets, Tom’s eyes revealed a racing mind. He could still see Manny’s upraised fists and feel the knots of Manny’s palm when they shook. The tough Portuguese boy had handed him a challenge, to rise above a human’s judgmental nature.

Then the thought hit Tom.

What if Manny had not been such a good guy after all?

Tom stared at the ceiling. Taking a chance—even to do the right thing—had almost cost him his front teeth. Never again, he decided.

From now on, Tom Hudner would be playing it safe.

CHAPTER 3

SWIMMING WITH SNAKES

A year later, April 1939

Lux, Mississippi

THE LATE AFTERNOON SUN CAST LONG shadows as a father and his three young sons trudged on the shady side of a dirt road. On one side of the road stood thickets of tall pines and leafy trees with thin white trunks. On the other lay parched brown fields where green plants sprouted.

Twelve-year-old Jesse Brown and his father, John Brown, pulled mules by the reins. Jesse’s tattered overalls looped over his slender frame. He was handsome, with sharp eyebrows, steady eyes, and healthy cheeks. A soaked T-shirt hung around his neck and dirt caked his bare feet. The air was hot and muggy.

Behind Jesse came his younger brothers—Lura, who was nine, and Fletcher, who was seven. The younger boys staggered barefoot in the heat, carrying hoes. Each had a fuzz of hair on top of his head and spindly legs that stuck out from overalls that their mother had cut into shorts. The difference was in their faces: Lura’s was square and lean whereas Fletcher’s was round and chubby.

Jesse Brown

Only Jesse’s father wore shoes, but they were falling apart. At five feet ten and 250 pounds, John Brown was built solidly, with a thick chest and muscular arms. Sweat poured down his round face and heavy cheeks. He kept his eyes focused contentedly forward. That night there would be food on his family’s table. It was the Great Depression, and Mississippi was the poorest state in the nation. Not everybody was as fortunate.

Jesse’s eyes drooped from sleepiness while his brothers struggled to walk in a straight line. Planting season had come in the Deep South and they’d all been at work since 4:30 A.M. Their fields lay in southern Mississippi near the crossroads town of Lux, little more than a gas station and general store in the woods. While the local white children remained in school, Jesse and his brothers were given a spring break from their one-room schoolhouse so that they and the other black children could work the fields.

For eleven hours that day, Jesse and his brothers had chopped plants until their backs ached and their hands were covered in blisters. Now they were headed home to do their chores; there was firewood to chop and chickens to feed and a garden to maintain. The garden was everything to the Brown family, because it was actually theirs.

As a sharecropper, John Brown didn’t own the thirty acres that his family farmed. He rented the fields from a skinny white landowner named Joe Bob Ingram, who also owned the town’s general store, where the sharecroppers rented their tools and bought their seed. Throughout the year, the store ran a tally on each family’s purchases. At year’s end when the bill was presented, Joe Bob always adjusted it to erase the Brown family’s yearly profit. For John Brown, it was a no-win life, one he hoped his boys would escape.

The father and sons approached a roadside footpath that led into the woods. Insects buzzed about the entrance. Lura and Fletcher perked up and grinned. With fresh bounce in their steps, the boys approached Jesse and tapped his arm, motioning toward the woods. Every day they came to Jesse at this same spot, with the same imploring eyes.

“Ask him!” Fletcher whispered.

Jesse knew what his brothers were hinting at and shook his head. He and his brothers still had to bring in the mules and do their chores.

The faces of the younger boys sank.

“C’mon, ask him—please!” Lura whispered.

Jesse looked down at his disheveled younger brothers. He felt exhausted too. Jesse’s face loosened and he steered his mule closer to his father.

“Pa,” Jesse said. “Do we have time for a quick break?”

Fletcher and Lura hurried forward and grinned toward the big man.

John Brown stopped to wipe his brow. He stroked the face of his panting mule, its eye half-closed. He had served in an all-black army cavalry unit during World War I, a unit that had been set to deploy overseas but the war ended before they could ship out.

John Brown looked at his boys and saw their raised eyebrows. His lips broke into a smile. “I’ll handle the mules,” he said. “Just do your chores when y’all get home.”

The boys glanced at one another with fresh life in their eyes. Jesse handed his father the reins to his mule and the boys handed him their tools. The family parted.

Lura and Fletcher took off skipping toward the forest path with Jesse following.

“Hold your horses!” Jesse called. At the trailhead he grabbed a sturdy stick from the ground, swung it through the air, and saw that it was good and steady. Jesse warned Fletcher and Lura to stay behind him.

Then he led the boys into the woods.

Jesse walked slowly and swept the path ahead with the stick. The trail wasn’t used much and weeds crisscrossed the dirt. The creaking and zipping from insects and croaking from bullfrogs were complicating Jesse’s efforts to listen for the hiss of a cottonmouth.

Cottonmouths were the thick brown-black vipers that infested the backwoods, and it was tough to spot one on a trail. They were poisonous, even more than rattlesnakes. The little girl next door to the Browns had been bitten on the foot. She lived, but only after sweating and groaning for weeks while blood bubbled from the wound.

Fletcher tried to race ahead, but Jesse stopped him. “Get back here, Mule!” Jesse shouted. He had nicknamed Fletcher “Mule” because the boy had a mind of his own. Fletcher stopped and grinned.

With his brothers behind him, Jesse resumed the march. He waved the stick at ground level and watched the trail, unblinking. One time, on the same trail, a coiled cottonmouth had threatened Jesse’s brothers and blocked their path home. So Jesse beat the snake’s head with a stick and killed it. When his brothers investigated the carcass they found a series of big bulges along its belly. Fletcher and Lura took it home and cut it open. Inside, they counted twenty-two frogs.

In the center of the woods, the boys reached a pond of stagnant water dammed off from a nearby stream. The water was brown and a thin layer of green scum floated around the edges. The boys stood a few moments and watched a snake crisscross the pond. Only its triangular head swam above the surface, its blunt snout parting the scum around its black eyes. There were always a few they couldn’t see, as well. The boys knew how to get the snakes out of their swimming hole.

Jesse unhooked his overalls and peeled his T-shirt from around his neck, then tossed it aside. He hadn’t even stepped out of his pants before Fletcher took off, naked as the day he was born, running down the dirt hill. Legs flailing, Fletcher jumped straight into the center of the pond. Lura followed and Jesse plunged in last.

Muddy water bubbled up from the shallow bottom. The scum shook and waves carried it toward the pond’s outer fringes. The cottonmouth didn’t like the disturbance. It slithered in retreat up the bank.

The muddy pond felt as warm as bathwater and the brothers splashed and paddled around, hooting and hollering to make as much ruckus as possible. Keeping the noise up was the best way to keep the snakes on the banks.

Dripping wet, the boys walked down the same dirt road as before, talking happily. Even after a bath in the muddy water, they felt clean.

Jesse smiled with amusement as he listened. Fletcher often jabbered about his girlfriends, twin girls who lived next door, whereas Lura knew all the current events from the newspapers left over after his paper route. For this reason, the family had nicknamed Lura “Junior” because he was like a junior Jesse, always reading.

The brothers paused their banter. Behind them, around the bend, a truck downshifted. It sounded imposing. The road was narrow, so Jesse led his brothers to the side and glanced back.

A school bus burst around the corner. It was black on the nose, yellow on the body, and its engine rattled like a laboring air conditioner. The bus shifted gears and picked up speed. Jesse edged his brothers farther into the weeds.

From the windows toward the back of the bus, a half-dozen white faces poked out, sporting mops of brown, blond, and red hair. The kids in the bus shouted a chorus of curses.

“Heya niggers!”

“Dirty niggers!

“Looky here, niggers!”

As the bus roared past, the kids spit at Jesse and his brothers. Sticky gobs of saliva splattered on Jesse and his brothers and stuck to their bare chests and arms as they tried to cover their faces. Dust and hot diesel exhaust enveloped the boys as the bus roared away. The kids in the bus stared back and pointed, laughing and whooping.

Jesse and his brothers frantically tried to wipe away the spit. They found it in their hair. Fletcher began to cry. He and Lura looked to Jesse for an answer. Jesse glared at the cloud of dust where the bus had been. He clenched his jaw and tightened his fists. He seldom lashed out and never cursed; instead he became tense to the point of shaking. He was “PO’d,” as he called it.

The brothers resumed their walk home in silence. It wasn’t the first time they’d encountered racial hostility, but usually it was just a curse or an angry eye when they walked into a store. Never had anyone spit on them. Never had they felt this dirty.

Lura’s flat eyebrows sank over his eyes with disgust. “I know what I want to be when I grow up,” he said, breaking the silence. “A Greyhound bus driver—so I can get the hell out of Mississippi.”

Jesse nodded. He was thinking the same thing.

CHAPTER 4

THE WORDS

Several days later

Lux, Mississippi

BY EARLY AFTERNOON, the heat struck the sharecroppers full force.

With his back hunched, Jesse Brown hoed between the shin-high cotton plants. Sweat dripped down his back, turning his overalls deep blue. He squinted at the acres of leaves ahead. The rows of green looked endless and the distant pines made the field feel like a prison.

In a nearby row, Fletcher swatted his face constantly. Gnats buzzed his ears and darted for his eyes. Only seven years old, he often lagged behind. Lura, at nine, could keep time with his older brother, but he was away that day with his father, watering the mules or fetching supplies.

Alongside Jesse and Fletcher, six farmhands hoed the furrows. For fifty cents a day, each helped the Browns during planting season. Women wore breezy cotton dresses and worked alongside men dressed in overalls and T-shirts. The adults all wore wide-brimmed straw hats.

Chop. Jesse took a step, then his hoe struck earth again. Chop. Jesse thinned the cotton by chopping any weeds between plants. The sun was white-hot overhead. Steamy air settled in the fields and breathing became difficult. Time seemed to stand still.

The sounds of the fields were uninspiring. Hoes jangling the dirt. An occasional sigh or grunt. The hock of a worker spitting. No call-and-response songs were ever sung in any field that Jesse Brown worked in. But sometimes there was music. Lost in a daydream, Jesse often hummed to himself. Fletcher and others would glance over to try to discern the tune. Sometimes Jesse hummed a slow folk song and other times a radio jingle.

At one point, it was Jesse who noticed that Fletcher’s hoe had gone silent. Jesse looked over and saw the younger boy rubbing his eyes with both fists. This happened often. Jesse walked to the end of the furrow, grabbed a jug of Kool-Aid, and carried it over to his little brother.

“Gnats getting to you, Mule?” Jesse asked.

The younger boy sniffed, wiped his nose against the back of his arm, and nodded. A gnat or two had found its way into his eyes and made them sting.

“They’re peeing in my eyes,” Fletcher insisted.

Jesse handed Fletcher the jug. Fletcher took a swig. The lemon-lime Kool-Aid was hot but sweet. Kool-Aid was a new invention and it cost just five cents a packet. Fletcher wiped his chin. A timid smile returned to his chubby cheeks.

He and his brother returned to work.

At first, no one heard it coming.

Not Jesse as he hummed.

Not Fletcher as he swatted away the buzzing gnats.

The airplane dived down from the sky. From across the field, Jesse heard a shout. A farmhand was pointing frantically toward the edge of the field. The man dropped to the dirt. Other sharecroppers were falling down too.

A BT-9/NJ-1

Jesse turned just in time to see a sleek blue airplane traveling toward him at treetop height. Its wings were low and yellow, its engine was round, and two large landing gear hung down from the wings—but the plane’s propeller wasn’t whirling. It was fixed straight across.

It was aiming for him.

Jesse ducked and dropped to the earth. Fletcher was already down. The pilot steered down a row of cotton. Jesse lifted his head and his eyes went wide. The plane was stretching larger and larger as it glided toward him.

Jesse buried his nose in the dirt and when he thought he would hear the plane smack the field and slide with a grinding groan, its engine whined, coughed, and bucked to life. Jesse felt the gust of hot exhaust as the plane roared over him.

The plane climbed, whistling toward the clouds. Jesse stood and studied the machine. The plane had a long glass canopy big enough for two men to sit one behind the other. The pilot—whoever he was—jerked the wings and wagged the red-and-white-striped rudder. It was a stunt. The plane had never been in danger of crashing.

“It’s that fool Miley boy again!” one of the sharecroppers yelled. Miley was a neighboring landowner whose son was training to be a pilot in Alabama.

Jesse envisioned the pilot and a redneck buddy having a good laugh at the black folks they had scared senseless. At the far end of the field, the plane turned above the pines. It was circling back for another pass.

“Head for the trees!” shouted a sharecropper.

In the center of the field lay a tall clump of oaks. The farmhands sprinted for safety. Some clutched straw hats as they jumped over the rows of cotton.

Jesse didn’t move.

He shaded his eyes with his hand and watched the distant airplane coming around. Fletcher stayed too. If Jesse wasn’t going to run, then neither was he, even though he was shaking.

A male farmhand darted out and hollered, “Fletcher! Jesse! Git your asses over here! That boy’s gonna kill you!”

Fletcher’s knees began to bend in terror, but Jesse didn’t flinch. The plane zoomed over the far end of the field and aimed at them. It wasn’t gliding now. Its engine was alive. The silver propeller blades whirled at shoulder height and the low-hanging wheels threatened to skim the dirt.

Jesse stood tall and stared right at the oncoming plane. The pilot hugged the earth, his prop wash blowing away the loose plants. The machine grew large in the boys’ vision. Its wings stretched. Fletcher hit the dirt and covered his head with his hands.

Just before the plane could cut Jesse in two, its nose pitched up. The pilot gunned the engine and the machine’s wheels soared over Jesse.

Fletcher looked up from the soil in time to see Jesse’s hands reach toward the wheels as the plane passed above his fingertips. The engine’s blast blew soil around the boys. Jesse shielded his eyes and then waved vigorously at the plane as it shrank in the distance. The farmhands ran to his side.

“Did you see that?” Jesse said. “A BT-9! I’ve only ever read about them.”

“You’re crazy!” one of the farmhands shouted. “That boy was trying to kill you!”

Jesse laughed and explained that the pilot would never have hit him—at that altitude the pilot would have crashed if he’d tried.

The other farmhands insisted that the pilot was out to get them. “He was up there laughing, yelling, ‘Run, niggers, run!’” one man said.

Jesse brushed the comment off with a grin. “He was just having fun. When I get my plane I’ll probably do the same thing to you!”

The farmhands broke into laughter. In front of them stood a barefoot thirteen-year-old boy dressed in stained overalls.

“Child, throw that idea straight out of your mind!” said a female field hand. “If Negroes can’t ride in aeroplanes, they sure ain’t gonna be flying one.”

Jesse’s smile faded. He returned to chopping but this time he didn’t hum. His shoulders tightened and his chin tucked. He was PO’d and not because the farmhands were ignorant but because they just might be right.

Several days later, after the farming was done, Jesse, Fletcher, and Lura walked on the dirt road, heading home to their chores. Dark storm clouds filled the horizon, a brewing summer storm.

Behind them came the distinctive sounds of a gear shifting and an engine rattling like a laboring air conditioner.

Jesse pulled Fletcher off the road into a nearby field and Lura followed. Jesse looked his brothers in the eyes. “If I say to run, then you run—get it?”

The younger boys nodded rapidly.

Jesse scoured the ground until he picked up a dried cornstalk about four feet long. He shook off the dirt and ran back to the roadside, the stalk in hand.

As the school bus neared, the windows slid back and the same angry faces emerged. Jesse stood to the side of the bus’s path and choked up on the cornstalk like a bat. As the bus passed, he swung the cornstalk and smacked the first face that jutted from the windows.

The angry face squealed and reeled back inside. The boy’s friends yelled at the bus driver to stop. The bus made a grinding sound and stopped. Jesse lowered the cornstalk but kept it in his hands. The boys in the back of the bus swore until a male voice barked, “Shut up!” The bus door banged open.

A white man in suspenders stepped out, spit tobacco juice, and strode toward Jesse. The bus driver was older, yet he had broad shoulders and big fists. Lura shielded Fletcher and glanced nervously up at Jesse, waiting for the order to run. Jesse remained still, his eyes fixed on the approaching driver.

“What in the hell just happened here?” the driver asked, his eyebrows narrowing.

“Sir,” Jesse said. “Every day when you pass us, those boys stick their heads out and spit on us.”

The driver’s eyebrows lifted. He turned and stared at his bus. The boys were leaning halfway out the window, like dogs with dangling tongues.

“C’mon, let him have it!” yelled the crying boy.

The driver turned and studied Jesse from head to toe, taking in the sight of the boy’s bare feet and patched overalls. The driver then glanced to Fletcher and Lura, who were cowering in the nearby field and looking up with frightened eyes.

“Well, that won’t happen anymore,” the driver said.

The man turned and strode back to his bus. The door slammed harder than before. The boys’ heads disappeared from the windows. Through the open windows of the bus Jesse and his brothers heard the driver chewing the kids out. Soon enough, the bus started and drove off with a grind and a roar.

When the bus was out of sight, Jesse and his brothers resumed walking home. The storm clouds still brewed in the distance, but things felt different.

After a few silent paces, Fletcher looked over at Jesse. His eyebrows were arched in astonishment. Jesse smiled, shrugged, and raised his hands, palms out.

His younger brothers broke out in laughter.

The rain was falling thick and heavy by the time Jesse and his brothers reached home, a cabin nestled in a thin grove of trees. The cabin was made of unpainted pine boards and was covered by a rusted tin roof. Kerosene lamplight flickered in the windows. The whole structure sat on blocks, a pile under each corner. Behind the home was a garden fence and then some railroad tracks. When trains raced by at night, the cabin shook.

Jesse and his brothers stepped onto the porch, where the mosquitoes had collected, seeking protection from the rain. The boys swatted the pests and entered through the cabin’s rickety front door.

John Brown was lumbering around the main room, placing glass jars under leaks from the roof. The cabin’s main room was for living, cooking, and sleeping. At night, Jesse’s parents slept there on a pull-out bed, while the children slept in a smaller room in back. The shack lacked plumbing; an outhouse served that role.

Jesse and his brothers wiped their bare feet with a rag that was kept near the door. Their brown shoes sat nearby and were being saved for Sundays, when the family attended church services. Jesse’s shoes had holes and so did his brothers’ shoes, but the holes had been filled with patches of cardboard and painted over with shoe polish.

“Look after your things, boys,” John Brown shouted over the rain that pinged against the metal roof. Julia Brown, the boys’ mother, was cooking on a wood-burning stove on the other side of the room. She was petite and trim and wore her short black hair curled behind her ears. Her face was strong and certain, with high cheekbones and intelligent eyes.

The boys greeted their mother.

“Hi, loves,” she said back. She was unfazed by the clatter on the roof and her toothy smile stretched widely.

John and Julia Brown

Jesse and his brothers ran to the smaller room in the back of the cabin. Between two beds sat a lantern on top of an apple box. The boys’ books and magazines lay in piles next to their beds. At night, Lura and Fletcher shared a bed with their older sister, Johnny, who was away helping her boyfriend’s family.* On the other side of the room, Jesse shared the other bed with his older brother William, who was shoveling coal for the railroad and wouldn’t come home until much later.

Jesse gathered up his dog-eared copies of Popular Aviation and stacks of how-to books—how to do magic, jujitsu, woodworking, and athletics—while Fletcher scooped up his mystery novels and Lura rescued his newspapers. The boys moved their effects to the driest corner of the room and then dragged their beds over their books. They had slept in wet sheets before and it was miserable.

Jesse and his brothers ran to join their father in aligning the jars under the leaks. On a clear night, they could see stars through the cracks, but now all they saw were flashes of lightning. With the leaking roof under control, the boys congregated near their mother. The warmth from the cast-iron stove dried their skin. Julia was almost finished with supper. Jesse’s favorite dish was his mother’s chicken pot pie.

“How was your day, boys?” Julia Brown asked.

Jesse shot his brothers a quick glance and answered for them. He told his mother that they had made good progress on the field. On their walk home, Jesse and his brothers had agreed not to mention the cornstalk incident.

Jesse knew that his actions had been dangerous. In the Depression-era Deep South, a black kid couldn’t just hit a white kid without inviting trouble. The white kid might go home and come back with his father and his father’s friends, or worse. There’d been a lynching six months earlier, just thirty miles down the road.

After dinner, Jesse, Fletcher, and Lura sat around the table with their mother and enjoyed dessert. The family grew their own sugarcane and made syrup, so sweets were never in short supply. Sweet potato pie was a family favorite.

John Brown rocked his oversized frame in a chair while reading a newspaper. As he read, he sipped sweet tea from a mason jar. A church-going Baptist, he served as deacon for the family’s forty-member church and never drank alcohol. Beside him, a wind-up Victrola record player played softly. When the record player slowed, John reached down and cranked it back to life. His favorite record was a musical containing the song “Ol’ Man River.”

After dessert, the boys and their mother always played what she called “the word game,” Julia’s attempt to make up for the schooling her boys missed during planting season. Before she married John Brown she had taught public school, and when Jesse and her boys were old enough, she resumed teaching Sunday school at the church.

Jesse, Lura, and Fletcher passed around a dictionary. Each chose a word and read its definition. Julia then attempted to spell it. The harder the word, the greater the challenge, and the boys groaned time and again as she spelled every word correctly. The boys’ older brother Marvin was away on scholarship at the all-black Alcorn College, intent on becoming a science teacher. But when he came home, even he couldn’t stump his mother. Embedded in the game was Julia’s hope that through education her boys could escape the fields forever.

Fletcher took the dictionary. He usually chose a word pertaining to medicine, as his dream was to be a doctor. His mother had always told him he could do anything he set his mind to—provided he got an education. When Lura took his turn, he often chose a word relating to geography. Jesse was usually the most excitable player. He’d look up aviation terms like dihedral and dirigible. But that night, he was mellow. His mind was in another place as the day’s events chewed at him.

“People judge you by the words you use,” Julia reminded Jesse and his brothers. “So choose the right words and say them correctly, the way they’re spelled. No ain’t. No whatcha doin’.” She looked at Fletcher, who laughed because he was the guiltiest.