14,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

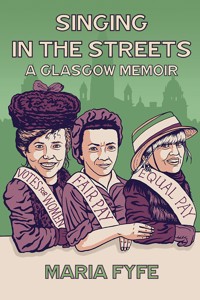

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

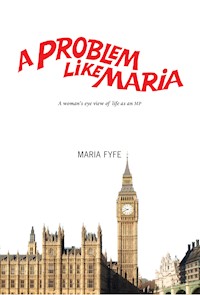

A Labour Whip once revealed that in their office they sang songs about certain backbenchers. In the case of the Member for Maryhill, their choice was 'How Do You Solve A Problem Like Maria? 'A frank account of fourteen years in Westminister from the rebellious Maria Fyfe - the only female Labour MP in Scotland when she was first elected. Fyfe recounts some of the most significant moments of her political career, from the frustrating and infuriating, to the rewarding and worthwhile. A significant aim of writing this book was to set the record straight on that period in our UK Parliament. Another aim was to encourage interest in a political life when widespread cynicism discourages good people from thinking about it. MARIA FYFE Covering some of the most turbulent years of British and Scottish political history, A Problem Like Maria takes the female's perspective of life as an MP in the male-dominated Westminister. This book reaches the parts of politics some people hope you never reach. The intimidating Maria Fyfe sounds like strong Scottish domestic drama. Edward Pearce, LONDON EVENING STANDARD The terrifying Maria Fyfe stamped in … her of the sharpened claws. Matthew Parris, THE TIMES An incorrigible Bevanite. THE OBSERVER

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 484

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

MARIA FYFE was the only female Labour MP from Scotland when she was first elected in 1987. She was an MP for 14 years for Glasgow Maryhill. In that time, she campaigned for poverty-stricken areas of the city in Parliament before stepping down in 2001. She has always been strongly politically active, campaigning for the equal representation of women in government.

A Problem Like Maria

A woman’s eye view of life as an MP

MARIA FYFE

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2014

eBook 2014

ISBN: 978-1-910021-04-0

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-88-5

The publishers acknowledge the support ofCreative Scotlandtowards the publication of this volume.

The author’s right to be identified as author of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Maria Fyfe 2014

For my sons, Stephen and Chris

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Michael Palmer and David Hendry, and the staff at Gartnavel Hospital, without whom I would not have been around to write this book.

Also Janet Andrews, Tom Brown, Catriona Burness, Malcolm Burns, Jim Cassidy, Anna Dyer, Liz Kristiansen, Jim Mearns and my brother, Joe O’Neill, for their useful comments, suggestions and encouragement.

I have tried my utmost to avoid errors: if any are present, they are mine and mine alone, and none the fault of those mentioned above. Any factual corrections will be welcomed, especially since a significant aim of writing this book was to set the record straight on that period in our UK Parliament.

Another aim was to encourage interest in a political life when widespread cynicism discourages good people from thinking about it. My third and final aim was to reveal the funny side of a Parliamentary career. Every walk of life has its jokes at its own expense and its absurdities, and Parliament could often be the best show in town.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Chronology

Chapter 1 I Could Have Danced All Night

Chapter 2 This Old House

Chapter 3 The Poll Tax

Chapter 4 Changing the Recipe

Chapter 5 Blacklists: A Blot on British Democracy

Chapter 6 Babies and Bars

Chapter 7 The First Gulf War

Chapter 8 On the Scottish Front Bench

Chapter 9 ‘New.’ But is it Labour?

Chapter 10 Clause Four – A Battle Royal

Chapter 11 1997: A New Dawn?

Chapter 12 Steps on the Road to Devolution

Chapter 13 The Fight for 50:50

Chapter 14 The Mike Tyson Battle

Chapter 15 Time to Go Home

Chapter 16 Ding Dong

Chapter 17 Where do we go from here?

Picture Section

Chronology

1987

General Election. Share of votes in Scotland: Labour 42.38 per cent, Conservative 24.03, Alliance 19.2 per cent, SNP 14.04 per cent, Others 0.3 per cent. First female MP in Glasgow Maryhill.

7,861 out of work in Maryhill, fifth highest in the country.

Poll Tax for England and Wales debated in Commons.

1988

January: Fight Alton Bill rally in Glasgow.

March: four months after start of Intifada against Israeli occupation, delegation sent to West Bank and Gaza.

Nigel Lawson’s budget reducing corporation tax for small businesses introduced.

April: Bill against Blacklisting introduced.

May: Glasgow May Day Rally.

24 May: Section 28 enacted.

May: visit to Nicaragua, invited by Sandinista women.

July: Campaign for a Scottish Assembly publishes ‘Claim of Right for Scotland’.

September: Tribune Rally at Labour Party Conference in Blackpool.

Conference votes to have a woman on every parliamentary shortlist.

10 November: Glasgow Govan by-election. Jim Sillars overturns 19,500 Labour majority.

21 November: Committees of 100 against Poll Tax launched.

24 November: first meeting of the Anti-Blacklisting Campaign.

1989

3 March: Scottish Constitutional Convention meets for first time.

Canon Kenyon Wright makes famous ‘We say Yes’ speech.

Numerous calls for gender balance in future Scottish Assembly.

14 April: SCC working group on women’s issues set up.

7 June: John Smith, Shadow Chancellor of Exchequer, sings theme fromNeighbours, mocking Thatcher/Lawson disagreement on Exchange Rate Mechanism.

9 June: Nigel Lawson, Chancellor of Exchequer, resigns.

18 June: Women’s Claim of Right published.

September: appointed front bench spokesperson on women by Neil Kinnock.

December: STUC Women’s Committee publish ‘Equal Voice for Women’. Call for 50:50 from Day One of Scottish Assembly.

1990

10 February: British-Irish Parliamentary Body founded.

March: riot in London against Poll Tax.

March: Labour Scottish Conference at Dunoon supports equal male/female outcome for seats in Scottish Assembly.

April: Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill.

August: Saddam Hussein invades Kuwait.

22 November: Margaret Thatcher stands down.

1991

15 January: vote in Commons to support war in Iraq (Maria resigns from front bench).

17 January: Allied commanders launch military offensive.

21 January: John Cryer tables amendment calling for peaceful settlement, but is not selected by the Speaker.

9 February: Labour Party Scottish Executive calls for a ceasefire.

15 February: Iraqi Revolutionary Council sues for peace, Britain and America reject proposals.

Harry Ewing, MP for Falkirk East, co-chairs with Maria new organisation, ‘Scottish Labour Against War in the Gulf.’

March: Labour Party Scottish Conference welcomes end of hostilities and liberation of Kuwait, calls for democracy in Kuwait, regrets action before sanctions exhausted.

September, Paul Foot inMirrortells about Economic League’s blacklisting.

Elected convener of Scottish Group of Labour MPs.

1992

April: Poll Tax abolished by John Major’s Government, Council Tax substituted.

April: General Election. Results in Scotland: Labour 39 per cent, Conservative 25.6 per cent, Liberal Democrat 13.1 per cent, SNP 21.5 per cent, Others 0.8 per cent.

SNP says its top political priority is destruction of Labour Party. Wins three seats.

27 April: Betty Boothroyd elected Speaker – first woman.

July: John Smith elected Labour leader with 91 per cent support.

10 July: ‘away day’ meeting of Scottish Group of Labour MPs discusses way forward.

Scotland United makes common cause with SNP.

July: appointed to Scottish front bench.

16 September: Black Wednesday. Britain forced to withdraw Sterling from European Exchange Rate Mechanism.

Interest rates up to 13 per cent.

November: Tory Government abolishes Wages Councils.

December: NHS Trusts to run Scottish hospitals announced to media but not Parliament.

Only three GPs in Glasgow choose to be fund-holding.

1993

Government announces plans to privatise water. Ten thousand at Labour/STUC rally.

August: White Paper for Children’s Bill (Scotland) published, 25 years since last legislation for children.

September: Labour Conference decides 50 per cent of selection conferences for new candidates in safe and marginal seats will have women-only shortlists. Still only three Labour women MPs in Scotland out of 49.

Scottish Homes survey reveals 95,000 houses below tolerable standard. Glasgow Director of Public Health reports half of households with children have dampness and condensation.

1994

Tribuneproclaims end of the Economic League.

March: Strathclyde Regional Council holds referendum on water privatisation. 70 per cent turnout, 97 per cent against. Government abandons plan.

12 May: John Smith dies.

October: Tony Blair makes his Clause 4 speech at Labour Conference. Jim Mearns, Maryhill delegate, calls for card vote.

November: given Scottish Education brief.

1995

March, Scottish Labour Conference approves Report, ‘A Parliament for Scotland’, calls for equal representation of men and women.

April: Government admits Poll Tax in Scotland cost £1.5 billion.

29 April: Special Conference of Labour Party on Clause 4.

October, resigned from front bench.

November: formal contract between Liberal Democrats and Labour on achieving gender equality in Scottish Parliament.

30 November: Scottish Constitutional Convention publishes ‘Scotland’s Parliament: Scotland’s Right’.

1996

February: William Duff, dentist, struck off. Later pleads guilty to fraud.

13 March: Dunblane massacre. Gunman kills 16 children and their class teacher.

September: TUC Conference. Stephen Byers says Labour planning to dump Unions. Neither Cabinet nor National Policy Forum has discussed it.

Kim Howells calls for humanely getting rid of word ‘Socialism’.

November: elected chair of Labour delegation to Council of Europe.

Elected chair of Scottish all-party group on children.

1997

May: New Labour wins General Election with over 13,500,000 votes and 179 seat majority. 418 Labour MPs, of which 101 are women. There are now eight Labour women MPs in Scotland.

In Maryhill, Labour wins 19,301 votes, SNP second with 5,037. Scottish parties’ support: Labour 45.6 per cent, Liberal Democrat 13.0 per cent, SNP 22.1 per cent, Conservative 17.5 per cent, Others 2.0 per cent.

Donald Dewar becomes Secretary of State for Scotland.

25 June: Tony Blair proposes two questions on Scottish Parliament, the second one on tax varying powers.

July: White Paper on Scotland’s Parliament published.

Backbench Labour committee on International Development created, self as convener.

8 July: debate on Glasgow housing – result £26 million to refurbish city housing.

Gordon Brown pays off £900 million Glasgow housing debt. Glasgow Housing Association formed.

11 September: Referendum on Scottish Parliament. Both questions win handsomely.

11 December: Lone Parent Benefit cut. Forty-seven Labour MPs vote against, 100 abstain.

17 December: Scotland Bill presented to House of Commons.

1998

Scotland Act: first line, ‘There shall be a Scottish Parliament’.

January: Labour women’s caucus set up in Commons and Lords.

National Minimum Wage Act passed.

October: Augusto Pinochet in London Clinic.

24 November: Queen’s Speech: Bill to remove right of hereditary peers to sit and Vote in House of Lords.

1999

25 January: vote on equal age of consent defeated.

30 March: Labour Government Employment Relations Bill makes blacklisting illegal.

April: Child Benefit for first child up 20 per cent.

12 April: Friends of Ireland, Friends of Good Friday Agreement launched.

Agreed Ireland Forum, elected Secretary.

First elections to Scottish Parliament. Labour 28 men, 28 women. Only party to deliver on 50:50. Women form 37.2 per cent of total elected.

12 May: Scottish Parliament meets for first time.

2 December: Good Friday Agreement came into force.

2000

Mike Tyson boxing match in Glasgow.

Clare Short publishes White Paper on World Poverty.

11 October: Donald Dewar dies.

23 October: Betty Boothroyd resigns as MP, Michael Martin elected Speaker.

21 December: Maryhill man, Ian Gordon, cleared of murder conviction following five-year campaign.

2001

January: after long campaign, VAT on feminine hygiene reduced from 17.5 per cent to five per cent.

March: International Development Bill, establishes in legislation reduction of poverty as aim of UK development assistance.

Unemployment in Scotland lowest since 1976, highest employment since 1960. Long-term unemployment down by 60 per cent since 1997.

May: General Election. Scottish results: Labour 43.9 per cent, SNP 20.1 per cent, Liberal Democrat 16.4 per cent, Conservative 15.6 per cent, Scottish Socialists 3.1 per cent.

11 September: Twin Towers attacked.

7 October: Afghan War declared.

2003

15 February: Marches against war in Iraq.

26 February:122 Labour backbenchers vote against support for USA again in Iraq.

17 March: Robin Cook resigns.

April: Tax Credits introduced.

2007

May: SNP form minority Government with Conservative support in Scottish Parliament.

30 June: attack on Glasgow Airport foiled by John Smeaton and others.

2008

Global economic crisis. National debt less than inherited from John Major in 1997.

2010

Regulations on blacklisting added by Gordon Brown Government.

2011

SNP forms majority Government in Scottish Parliament. Women MSPs now down to 34.8 per cent.

July onwards: hacking scandal begins to be exposed.

December: Johann Lamont elected first Leader of Labour Party in Scotland.

2013

April: ‘Bedroom Tax’ hits.

8 April: Margaret Thatcher dies.

CHAPTER ONE

I Could Have Danced All Night

1987

IN THE 1987 GENERAL ELECTION only one female Labour MP was elected in Scotland. Me. It seems hard to believe now, but back then female MPs were rare creatures indeed. Of course everyone knew there was a Queen Bee at Westminster, frequently spotted in her Downing Street habitat. If there were precious few other women in Parliament, that didn’t matter a jot – to many, across all political parties.Women belonged in the home, not the House.Let the best man win. This opinion was widely held by the frequent fliers to Westminster, where they gathered together and drank at their watering holes. How could their favourite son succeed them if uppity women could have a go?

Now here I was, newly elected for Glasgow Maryhill, one of Labour’s safest seats.

That day, Britain elected a record number of women MPs, a 78 per cent increase over the previous General Election in 1983. That meant a total of 41, compared to 23 at the previous election. The 41 consisted of 21 Labour, 17 Conservative, two Liberal-SDP Alliance and one Scottish Nationalist. Despite that upswing, women still only accounted for 6.3 per cent of total MPs. Scotland was even worse, with only 4.16 per cent. That amounted to three women out of a total 72 MPs: Margaret Ewing for the Scottish Nationalists, Ray Michie for the Alliance and myself. I knew before the election was even called I would be the only Labour woman in Scotland, because the few other female party members who had been selected to fight a seat were doing so in constituencies they were highly unlikely to win. I vowed I would do everything in my power to get more Labour women into Westminster.

In the run up to the election,The Scotsmanran brief commentaries on all the seats. For my own constituency it said:

Glasgow Maryhill has returned a LabourMPin every General Election since the Second World War, and it would probably need a comparable cataclysm to unsettle political allegiance to any significant degree in this Socialist citadel.

Amen to that. So why couldn’t my sisters enjoy their share when it came to winning similarly committed constituencies? I will never forget the tiny old lady, who looked about 90 but had a firm step, approaching me outside a polling station in 1987 to tell me what a great pleasure it was to be able to vote for a woman for the first time in her life.

For the first time inmylife I had found myself under attack in the press. Previous media attention had, if anything, been complimentary about my activities as a councillor. Now theNews of the Worldwas claiming that I opposed the expulsion of Militant Tendency supporters from the Labour Party, when in fact I was entirely hostile to their activities and aims. They were using the Labour Party for their own ends, and fellow left wingers who defended them were profoundly mistaken. This was not a point of view I had been shy to express, especially in my years as a Glasgow councillor, fighting Tory cuts as well as seeing off the Trots.

Not that the Murdoch press had it in for me alone. Similar claims were made against Clare Short and Neil Kinnock, of all people – remember his attack on Derek Hatton for the mess he made of Liverpool? – as well as many others. TheSunday Timesran a headline, ‘Kinnock’s Hard Left Nightmare’, and listed me along with Tommy McAvoy, who went on to be a senior Labour whip and member of the House of Lords. Scottish Secretary Malcolm Rifkind, not to be outdone by Rupert Murdoch’s distortions, disgraced himself when he named eight Scottish Labour candidates, including myself, as ‘infected with the same left wing virus as the “Loony Left” in London, and well to the left of those retiring’. I was indeed to the left of my own predecessor, but the excesses of some in the Party in a few of the London boroughs were not for me (although I must put it on record that many of the stories told about them were exaggerated or simply not true).

Going by their future careers, if Tommy, Adam Ingram (Defence Minister), John McFall (Treasury Select Committee Chair), Henry McLeish (First Minister in the Scottish Parliament), and John Reid (arch Blairite and holder of several posts at Secretary of State level) were indeed hard left, how would they describe the rest of us? Another edition had several of us listed as ‘Kinnock’s 101 Damnations’. Beneath an unflattering picture of each candidate was a description of our views that upset theSunday Times. This went down well with Maryhill Constituency Labour Party. Other Labour candidates jokingly claimed that they were jealous, wondering why they too had not been attacked. Why, they demanded, were they being denied this useful dose of street cred?

While some in the leadership were concerned about such attacks, my own view was that I would start to worry the day the Murdoch press praised me. I have kept a copy of my election address as a keepsake, and I see that I questioned ‘why financial skulduggery should earn more than a lifetime’s honest work’. Can’t have left wing stuff like that, can we?

Though I was the Labour candidate for super-safe Maryhill, I was nervous of letting down the Party in any way. Considering the treatment I had been receiving from Murdoch’s minions, I felt anxious when a reporter fromThe Sunphoned to ask me for an interview. I lay awake worrying about what this portended. Was he running some anti-Labour story? Was some scandal about to unfold? I was confident my sons were neither drug addicts nor pushers, neither drink drivers nor hooligans, or advocates of any ultra-left idiocy, so could it be something to do with the local Labour Party? I had no reason to think so… Helen Liddell, now a member of the House of Lords, at that time secretary of the Labour Party in Scotland, had told all of the new candidates to phone her if we had any problems. So I did, and she advised me not to worry.

‘Put on your best dress and have some flowers around the house. Hide away your more left wing books in case he notices them. Oh, and have something baking in the oven.’

‘But’, I protested, ‘no-one bakes wearing their best dress. They’ll think I’m an idiot.’

‘Not at all’, said Helen. ‘They’re men. They won’t know any better.’

Nevertheless, I was nervous enough that I asked the reporter to meet me at my campaign rooms, rather than my house. That way my agent, John Gray, would be a witness if I needed one. John himself was a much respected and well known councillor. When the reporter showed up he was all joviality, but I still did not feel reassured. Just at that point, a woman with a problem she wanted me to look into turned up on the doorstep, so John took her into the back room for a cup of tea until I could make myself available. That was my attempt at precaution fallen apart.

I turned reluctantly to the reporter. What he wanted to do, he explained, was a piece contrasting me with Anna McCurley, the well known Tory MP seeking re-election in Renfrewshire. So, what issues did he have in mind, I asked.

‘No,’ he replied, ‘nothing as heavy as that. It’s because she’s a blonde and you’re a brunette.’ Ye Gods! My late husband Jim, a reporter himself, had a way with that kind of thing. He once submitted a piece which described the local Fire Master as blonde and petite. When the editor said, ‘You can’t write that!’ Jim replied that the paper described women like that all the time, even when her height and colour of hair had absolutely nothing to do with the story.

The man fromThe Suntook down some personal details while the photographer readied himself. When he pulled a long-stemmed red rose out of a bag and asked me to put it between my teeth, I politely declined. I wasn’t about to burst into Carmen’s ‘Habanera’.

‘Then how about in your hair? No?’

‘No. Definitely not.’

At least these guys are drawing the line at asking me to do a Page Three, I thought. They seemed to mean well, even if they were reducing politics to a level of triviality I had never before encountered. I suggested cutting the stem and fastening it to my dress, to which they reluctantly agreed. The subsequent piece did neither Anna nor me any harm, but Anna lost her seat to Tommy Graham in that year when Labour won 50 seats in Scotland.

Maryhill Labour Party was not the first to publish a leaflet addressed to women voters – all the parties had done that during the inter-war years, just after the franchise was extended – but it had never been done, as far as I know, in my own years of involvement in politics. In it, I took up issues such as equal pay, elimination of low pay, and much greater provision of nurseries for the under-fives in their own localities.Cosmopolitandid something unusual for a woman’s magazine until then: it asked readers to identify the three issues that were of most concern to them, then asked all candidates, male and female, where they stood on such matters. I was happy to support married women being taxed as individuals, sufficient money for a national programme of screening for cervical and breast cancer, and better services provided for those least able to look after themselves, thus creating more help for carers. Eventually the first two were won, but carers are still without the level of help they need. We hear of elderly and infirm people who have no-one living with them to help with their daily needs, getting no more than 15 minutes of a paid worker’s time. There is no time for conversation, as she hurries on, unpaid for the travelling time between jobs. This is a national scandal, and nothing to boast about.

That year, at the behest of Jo Richardson, our Shadow Minister for Women, Labour promoted a Charter for Women and Work, and undertook to create a Minister for Women in a future Labour Government. The Tories scoffed at such notions. They evidently could not foresee the day when David Cameron would appoint his own Women’s Minister, and now national screening for breast cancer is so taken for granted that I doubt that any Chancellor, however cutbacks crazy he is, would dare to end it.

And so, as the weeks went on in the run up to polling day, I went around Maryhill, knocking on as many doors as possible, morning, noon and night. One afternoon, having sent party workers away to help in a marginal seat, I decided to go on my own to The Botany, an area of Maryhill since transformed, but at that time very run down and its tenement flats far fromdes res. It was called The Botany because back when even the theft of a loaf for your starving family could have you deported to Botany Bay, you would start your journey on board a vessel moored nearby on the Forth and Clyde canal. Then you would sail to where the canal met the River Clyde, and transfer to an ocean-going bound for Australia.

I rang a doorbell and was invited in. The man who answered went on to tell me how difficult it was finding a job: not an unusual problem in Maryhill at that time. I asked him sympathetically if he was getting interviews. He said, ‘Not even that. As soon as they read I’ve been in prison that’s the end of it.’ So I asked him what his sentence had been for. ‘Arson’, he replied. ‘I don’t even know why I did it.’ I retreated step by step towards the door and made my exit. Back in the campaign rooms, I told John Gray about it. ‘You stupid besom,’ he scolded me. ‘Don’t you ever go out knocking doors on your own again – and for God’s sake don’t go into anyone’s house when there’s nobody around to see where you’ve got to.’ And so he went on to put his foot down and protect me from myself for the next 14 years.

I plodded on without further mishap until, at last, the day of the General Election arrived. More than two thirds of the Maryhill electorate voted. That was a typical turnout of the time, but it has been falling since. The highest results, other candidates having a few hundred or less, were:

Elspeth Attwool, Lib/SDP Alliance 4,118

Maria Fyfe, Labour 23,482

Simon Kirk, Conservative 3,307

Gavin Roberts, SNP 3,895

David Spaven, Scottish Greens 529

Labour’s share of the vote was 64.6 per cent. Elspeth Attwool came second, but her percentage share of the vote was halved from 22.1 per cent in 1983 to 11.7 per cent. The SNP came third with 11.0 per cent, the Tories fourth with 9.4 per cent, and the Greens took 1.5 per cent. The SNP were still suffering from having brought down the Callaghan Government and let in Margaret Thatcher, and the Tories always did very poorly in a seat like Maryhill.

So Labour’s majority in Maryhill was a thumping, joyful, unbelievable and glorious 19,364 – about 8,000 more than our previous result. All over the city, similar results for Labour candidates were announced. Many a previous majority, including my own constituency, had been doubled. But then, not many copies of theSunday Timesare sold in Maryhill. I felt a sense of awe that all those people voted Labour, and few had even heard of me before I became the candidate. They had trusted Labour again and again, and I told myself I must never let them down.

The GlasgowEvening Timeswrote:

Throughout a night of high drama, the picture was constantly repeated. In Scotland and the North, Labour increased majorities, snatched seats, the Alliance was smashed, and the Tories were lucky to scrape home in some seats they have held for generations.

The SNP didn’t warrant a mention. The share of votes in Scotland was:

Conservative 24 per cent

Labour 43.3 per cent

Alliance 18.4 per cent

SNP 14 per cent

Others 0.3 per cent

I felt a joy on election night that was unique amongst the successful Scottish Labour candidates. As I stood on the platform with my sons, Stephen and Chris, nearby, I reflected that I had just become Labour’s tenth ever woman to be elected in a Scottish constituency.

But I didn’t want to settle for being a Queen Bee amongst all the men. My task now was to make things better for women. At the following year’s Scottish party conference, I made a comment that seems to have stuck in a lot of minds, as I have had it repeated back to me many times: ‘Labour likes having women MPs, but it likes them one at a time.’

You have probably noticed, when watching Parliament on television, jugs of water and glasses sitting on the table close to the despatch box. They are meant for the use of frontbenchers. On the night I was to make my maiden speech, I was so nervous that my throat had gone completely dry. Some kindly soul handed me up a glass, and I drank it down hurriedly in case I were called by the Speaker, nearly giving myself hiccups in my haste. But then I thought to myself, the people of Maryhill sent me here to speak up for them, and I’m going to do that to the best of my ability.

I began by commenting on Labour’s huge success in my home city, saying Glasgow was the city that had everything – except a Tory MP. I went on to attack the Government on the continuing high levels of unemployment in Maryhill: 29 per cent of adult males, and in Woodlands ward, where I lived, 34.4 per cent. Half the youths in that ward were unemployed.

I drew attention to something I learned while studying for my Economic History degree: when the Forth and Clyde canal which runs through Maryhill was completed in 1784, it was made possible by a cash grant of £50,000 (£25 million at 1987 prices) from William Pitt’s Tory Government. The private company that had started up work on the canal had become ‘a lame duck’ in the Conservative parlance of Margaret Thatcher’s day. It had run out of money and could not raise enough cash on its own. Back then, all those years ago, the Government did not shrug their shoulders and let it fail. They had the wisdom and foresight to put serious money into the scheme, and in doing so created jobs all the way along the canal. Maryhill prospered. Mining, glass-making, chemical, engineering and other industries flourished, but by now were mostly gone. Would that present-day Conservatives, I went on to say, had anything like as much sense as their predecessors of some 200 years before.

The Speaker, Jack Weatherill, was thoughtful enough to send me a ‘well done’ note, but the kind man probably did likewise with everyone. When walking down the Ways and Means corridor later that night, I was stopped by a Tory backbencher I had never met before, but came to know as a decent bloke. He said I sounded as if I hated the Conservatives. Considering what they were doing to my city, to working people’s rights, and the massive unemployment they had deliberately created as a means to weaken the trade unions, it would be surprising if I did not hate them, and I told him so. He was quite taken aback because the parliamentary convention up to that time was that maiden speeches should be uncontroversial, and be received politely with no heckling or abusive behaviour.

And, of course, there was the Poll Tax. TheGlasgow Guardian, our local weekly, ran the story on their front page with the banner headline, ‘Maryhill MP Hits Out Over Poll Tax’. I had questioned in Parliament why the Government had come up with a scheme that was so monstrously unfair, and had been described by Local Government accountants as an administrative nightmare. I pointed out the average rates bill for a household in Glasgow was £514, but the Poll Tax would be £292 per head. So a two adult household would pay a huge amount more than before, and young family members over eighteen would have to fork out the same, despite being more likely to be on much lower wages than their elders.

I expected political points to be made through heckling. That was fair enough. I did it back to them, and relished doing so. What I had not expected was the kind of boorish behaviour that would draw a reprimand from any schoolteacher in the classroom, but went unremarked by the Speaker or his deputies until it got out of hand. I could not believe my eyes and ears when I began to notice what happened sometimes when women got up to speak; on the first occasion it was Clare Short. She was on her feet, deploring the demeaning of women in theSunpage three pictures. Some Tory backbenchers were loudly scoffing while they made cupping motions with their hands at chest level. I made up my mind then that if they ever did that to me, I would stop mid-sentence and say, ‘Mr Speaker, I understand only Members are permitted to sit in this Chamber, but somehow some ill-mannered adolescents seem to have found their way in.’ Shows how much I had to learn about the place. No Speaker likes to be told, in effect, he is not doing his job. When things get so unruly he cannot hear a Member speak, he has to shout, ‘Order! Order!’ and repeat himself five minutes later when disorder has broken out again.

I didn’t see it at the time, but now, looking back, I see that kind of behaviour as a none-too-subtle attack on our very right to speak. A politician’s main tool is her or his voice. If you are unable to be heard, you are quite literally silenced. There had been a miners’ MP some years before me. He had been an effective union man, and so they sent him to Parliament. But he was so intimidated by the atmosphere in the Chamber that he gave up trying to speak, and never set foot there again to utter even a question.

Another extraordinary aspect of my new life was the feeling that I was travelling backwards in time. I had occasionally worn trouser suits to my work as a Further Education lecturer since the mid-’70s, but it was frowned upon when I turned up for Parliamentary work one day in the smartest suit I had. The ladies, I was told, were expected to wear skirts or dresses. I told anyone who made this comment that no-one since I was a schoolgirl had ever told me what to wear, and now that I was middle aged, they weren’t going to start now. Today we can see women members wearing smart trousers, and it is taken for granted. Progress creeps along. But the Commons still has the pink ribbons attached to the coat hangers in the Members’ cloakroom, where you can hang your sword in safe keeping because you will not be permitted to take it into the Chamber. Well, debates there have been known to get heated. So why, in the name of all logic, do they still have the red lines going the length of the green carpet, two sword lengths apart? One of my colleagues thought it would be a good laugh to buy a sword, hang it on his ribbon, and claim whatever it cost on expenses, as obviously the Parliamentary authorities must think each of us needed one, or they would not supply a ribbon on every coat hanger to hold it. In light of recent events, I am glad for him that he desisted. It must be the better part of two centuries since men last went about ready to draw sword, except of course for those younger ones in some of our big cities, whose favourite pastime is gang warfare. Regardless of such realities, some love this kind of tradition. I find it merely irritating. Besides which, it gives the impression that nearly a hundred years on since female emancipation, the institution has not yet caught up with the entry of female members. Apart from Boudicca and Britannia, one would be hard-pressed to think of any sword-wielding women.

So we had ribbons for non-existent swords, but no waste paper bins. When I started to attend meetings of numerous committees I found it surprising that members tossed papers they were finished with on the floor – and we got through a great deal of paper. Thinking, ‘Why is it all these men have not a notion of how annoying it is for others to have to pick up after them?’, I asked the chairman if he would get some bins supplied. He explained to me that doing so would be against the traditions of the House. Therefore the cleaners had to waste effort, bending up and down along all the rows of seats in 16 committee rooms? He had an answer to that too. ‘Surely you, a Labour member, wouldn’t want to throw them out of work?’ Maybe they could do some more useful work, I thought, but I was beginning to see what I was up against.

Nor had we new boys and girls known about the daily ritual of Prayers before business in the Chamber began. Members would turn round and stand facing the wall, because you could not be properly reverential if you were facing your opponents. And you were not allowed to clap. The day we opened for business, all the new Labour members began clapping when Neil Kinnock walked into the Chamber. A senior member turned round and told us we must not clap. That was not proper Parliamentary conduct. We should say ‘Hear, hear’ or tap the bench in front of us. Five minutes later he was yelling abuse across the Chamber.

I was only in the place a month when I got into a row over the dining habits of some of the members. I had received an invitation to enjoy a free bottle of champagne at Lockets Restaurant, near the House of Commons. I had not realised until then that some restaurants, including Lockets, had division bells, calling Members to the House for a vote, so a nightly scene in them would feature MPs bolting for the door. Lockets, their invitation said, prided themselves on keeping their meals warm, or if an MP was delayed, replacing it. I was miffed because I remembered only too well the night I was sitting up in the Gallery, hearing the division bell ring, and seeing Tory MPs in their dinner jackets pouring hurriedly into what had been an empty Chamber to vote to cut Glasgow’s money. I had not known until then that MPs could and did vote following a debate they had not even heard. It was that very night that I decided I would like to be a Labour MP and stand up for Glasgow.

I was accused of being hair-shirted. But if we started earlier in the day, and finished at a sensible time, everyone could spend as long as they wanted in restaurants, with no division bell to make them bolt their food down.

Scottish MPs, male and female, would be heckled with what some Tory idiots obviously thought was wit: ‘Speak English, will you’, they would shout in public school accents, either genuine or cultivated. When someone did that to me, in a debate not long after I entered Parliament, I countered, ‘If the honourable gentleman doesn’t understand my accent, that is the least important thing about Scotland that he doesn’t understand.’ None of my colleagues were in the Chamber at the time to back me up, but the SNP’s Alex Salmond, elected for the first time that year like me, complained about the insult. It was a gift to the SNP, and he wasn’t going to miss the chance. To my surprise, the incident was reported in a Canadian newspaper, which I only heard of because someone in Ontario sent me the cutting, with an approving comment on my riposte in the editorial. But what makes these MPs behave in such a crass way? If I could understand Cockney and Scouse and Zummerset, and would never dream of pretending I could not, what was wrong with their ears? We would sarcastically advise them to watchTaggartorRab C. Nesbittuntil they got the hang of it. One guy, who did watchTaggartregularly, asked me in all seriousness how a woman had come to be the MP for a tough place like Maryhill. I informed him that this series was fiction, not a documentary. We did not have all these murders every week, just some, occasionally. John Smith once remarked to me that they could not place us socially, because their ears were not attuned to the variety of Scottish accents, and that bothered them.

The boorish behaviour was even continued in the dining rooms, where some Tory members would bray so loudly that people seated at neighbouring tables could hardly hear each other speak.

When my brother Jim, dining with me one night in the Strangers’ Dining Room, heard this for the first time, he dealt with it in a way that never would have occurred to me. He began by loudly declaiming: ‘Bray, bray, bray, bray, bray.’ Then, putting incredulity into his voice, he asked, ‘Bray???’ Answering himself, he nodded gravely, and cried ‘Bray!’

They got the message.

New members, back then, found themselves in a place of work where there was not even the smallest of offices to accommodate all of them. I was allocated a desk in The Cloisters, a gloomy quadrangle of ancient grey stonework with a patch of grass in the middle, where so little sunlight reached that I could hardly read my papers. The electric lighting, such as it was, barely competed with church candles. Down each side of the square there were placed a number of ancient moquette sofas. They never seemed to be vacuumed, and if you hit the seat clouds of dust would rise. That summer, when hotel rooms were hard to find, particularly during Wimbledon, Tommy Graham, newly elected for Renfrewshire West, occasionally ended up sleeping on the sofa nearest his desk. Well, it was better than a park bench, where he had also slept on a few warm summer nights. With his shirt buttons popping open over his ample stomach, he lay snoring when the rest of us arrived in the morning: it was not a pretty sight. It was so hard to find accommodation that, one night, after one fruitless phone call after another, I ended up in a suspiciously cheap hotel in Victoria. Neil Carmichael, an old chum and former MP for Glasgow Kelvingrove who was now in the Lords, had suggested I try it, although he himself had not been there for many years. My fears were more than vindicated. When I arrived late at night after the final vote, I noticed that the carpet in the foyer had chewing gum trodden into it in several places. The walls were brown with years of tobacco smoke. The lock on my bedroom door was broken, so I had to push a chest of drawers up against the door, in case I was disturbed by any of the drunken Australians rampaging up and down the corridor. I left first thing next morning, without risking breakfast.

In the Quad individual desks were placed behind one another all the way around its four sides. Tommy, who suffered industrial deafness, spoke so loudly on the phone three desks back that I could hear every word he said. Keith Vaz, immediately behind me, would be on the phone almost daily, scolding the editor of his local paper, something that had never once crossed my mind to do. I might write a complaint, but who except Keith would talk to him as if he were a naughty boy, and threaten to put him over his knees and spank him. It was small consolation that, immediately at my side, there was a tiny room of historic importance: it was here that the warrant for the execution of Charles I had been signed. If I didn’t get out of this place soon, I mutinously thought, I’d be signing someone else’s death warrant. Even 20 years ago, as a young secretary with the Scottish Gas Board, I had better office space than this. I discovered others were succeeding in moving out to better accommodation. The Whips, who organised these matters, were already identifying their favourites. Even worse, I gathered that some members curried favour by giving presents of flowers and chocolates to the wives of certain whips. And lo and behold! Suddenly a room could be found for them. So I marched to the office of Derek Foster, Labour’s Chief Whip, and told him that if I didn’t soon have a desk somewhere in peace, I would be offering a sarcastic poem about the working conditions of a new MP toTribune, the mainstream Labour left weekly, widely read by party members. I got my office, albeit shared with two others, but it was close to the committee corridor and therefore highly convenient. Others had to run back and forth in the rain from outer offices when the division bell rang.

Nowadays there are splendid offices across the road in Portcullis House, reached by a conveniently sheltered underground walkway, allocated to new Members immediately they enter Parliament. That office block, by the way, cost far more to build than the Scottish Parliament, but I have never seen a word of complaint about that in the media, although they droned on endlessly about Holyrood’s spiralling costs.

In the old building the carpets on some of the staircases were so worn they were a danger. I grumbled about this one day to John Smith as we walked down a staircase together, saying that with all the money wasted in this place on, for one example, ridiculously expensive wallpaper, you would think they could renew the carpets. He laughed to hear what he called a typical Scottish housewife’s remark.

And then there were the mice. I was somewhat startled one day when, having a cuppa in the Members’ Tearoom, I saw a mouse run across the floor. I was languidly told they were a permanent, if fairly infrequent feature, because the Houses of Parliament were so close to the Thames. Why not get a cat? I asked. The answer was that no-one wanted to take responsibility for it when the place was closed during the recesses. Here we were, running the country, but finding a cat too much to cope with. In recent times there have been three or four cats in Downing Street, but to the best of my knowledge the Commons has still not got around to that solution. They still, all these years later, have not found a way to deal with the mice.

However, in spite of all my frustrations at some of the baffling, outdated and frankly ludicrous attitudes and customs of Parliament, I loved being there. It was like nowhere else on earth. To me, becoming a Labour MP was a dream come true, and a privilege to be treasured.

CHAPTER TWO

This Old House

1987

AT THE FIRST SCOTTISH Question Time after the 1987 General Election, when the Tories had won UK-wide, but not in Scotland, the government benches in the Chamber were packed with Tory backbenchers from constituencies in England. At that time in Scotland, there were 62 Opposition, including 50 Labour Members, and only 10 Conservative MPs. Some of those ten had ministerial positions in other departments, so there were only a few Scottish Tories present. The Speaker took questions turnabout from side to side, like a metronome, as is done at all ministerial question times. It was difficult to get a chance to ask a question at all, because there were so many Labour MPs holding Scottish seats, and the Speaker would call equal numbers of Members from the other side of the Chamber. It did not matter that they came from the Tory shires and the posher parts of London, attending just to curry favour with their whips, or as a device to raise something concerning their own constituency. Indeed, sometimes Tories whose seats were outside Scotland were called twice in the one session, when many Labour MPs with constituencies in Scotland were not called at all for months on end. It was a bit of a giveaway when some of these Tories, pretending an interest in Scottish affairs, could not pronounce place names like Milngavie or Tighnabruaich. In effect, in those days before Parliament was televised, Labour’s electoral success in Scotland was being hidden from radio listeners, and it would sound as if we were equal in numbers, when we had in fact beaten the Scottish Tories out of the park.

Televising parliamentary proceedings would have let viewers see that at least we were present and doing our best to be heard. Dennis Canavan, indignant that this was happening at the first Scottish Questions of the new Parliament, and to draw attention to it, shouted out ‘I spy strangers!’ This historic cry goes back centuries to when the Commons had to protect its autonomy. When such a call is made, a vote has to be taken to decide whether to clear the public gallery. I voted with him, thinking this was a good wheeze. Dennis pointed out he was not objecting to the tourists passing an hour in the gallery. They must have been wondering what on earth was going on, and why they were being evicted when they had done nothing wrong. His ire was directed at the Tory MPs from constituencies in England who had no real interest in Scotland. However, Donald Dewar told us he should not have done that. He disagreed with Dennis’s argument that the Tories had no mandate to rule over Scottish affairs, having had such a humiliatingly low level of support at the recent General Election. Donald’s view was that, nevertheless, the Tories had won a UK-wide general election. What would Dennis say if Labour had won in England and the Tories in Scotland? In my view you didn’t need to support the ‘no mandate’ argument in order to draw attention to the fact that the run of questions gave the wrong impression of relative strengths when it came to Scottish affairs. And here we are now, with a Con-Dem Government, and only one Conservative MP in the whole of Scotland. Except now there is a huge change for the better. Nowadays we have a Scottish Parliament to deal with devolved issues, and no-one was more wholeheartedly in favour of achieving that than Donald himself. It still leaves us with the same nonsense, though, for Scottish Questions at Westminster.

1987 was the election that threw up what was called ‘the democratic deficit’, and the devolution debate came to life again. It was Jean McFadden, former Leader of Glasgow’s Labour Council, who made a point to me that, until then, I had never considered: we really needed a Scottish Assembly, because when Whitehall ruled the roost, even when there was a Labour Government, the needs of Scottish councils could be ignored. It would be harder for a parliamentary body ruling Scottish domestic affairs to be so detached from the consequences of its actions. I think this is proving true. The Nationalist Government forced Scottish local authorities to accept a council tax freeze, on pain of getting a larger cut in their grant if they refused – and went on to cut the grant even further than promised, as well as imposing the freeze for several years. But knowledge of this kind of thing is nowadays much more widespread and commented on in the Scottish media. I don’t think any of us anticipated that we would one day have a Scottish government that was as centralising as this one.

We continued to fight back against the Tories at every Scottish Questions session. Other members came in to enjoy the spectacle. Frank Dobson said he could sell tickets for it. I don’t know why we were unlike other parts of Britain, but Scottish Labour members at that time seem to have gained a reputation for getting stuck in, for being forthright, for having no deference to any Minister, however exalted, and generally being as difficult as human ingenuity could devise.

George Foulkes, angrily getting in a reply to Douglas Hogg one day, called him ‘an arrogant little shit’. When the Speaker indignantly rose to his feet and ordered him to withdraw that word immediately, George coolly asked him, ‘Which word do you want me to withdraw, arrogant, little or shit?’ Back home, people came up to George in the street and said, ‘Good for you! Wish I could have been there to say that!’

I was particularly irritated by Philip Oppenheim, whose mother was also an MP at that time. A fairly young Tory, tall, blond-haired and born with a mouthful of silver spoons, he made a habit of attending Scottish Questions. There was always a disdainful sneer on his face when he spoke, looking across to the Labour scruff on the Opposition benches. So one day I called out that if he insisted on making that face, he would stay like that when he grew up. Some have said that was ageist of me. I think if an adult behaves like a brat, then he has only himself to blame if he is treated like one.

We thoroughly enjoyed these sessions, lambasting the Tories. Yet the Nationalists had the gall to dub us ‘the feeble fifty’. That was some nerve, coming from a party that had won only three seats in Scotland in 1987. The voting public were continuing to make them pay for colluding with Margaret Thatcher eight years before in bringing down James Callaghan’s Government, and landing us with all that Thatcher went on to do.

Getting called in debates, as well as questions for ministers, was a constant struggle. I thought, particularly as I was the only woman out of 50 Scottish Labour MPs, I should expect a right to my fair share of chances to speak, particularly when matters relating to women were being debated. Indeed, that was the ruling logic when Parliament was debating, for instance, agricultural affairs. They wouldn’t have dreamed of having any such debate without calling MPs from the shires. And yet, when we had a debate in the Scottish Grand Committee on the running of Corntonvale, the only all-female prison in Scotland, I was finally called to speak for exactly one minute, after other speakers had taken their full ten minutes, and before the front benchers made their closing speeches in the debate. I had a particular point to make about the narrow curriculum of education and training offered to the women, when male prisoners were offered so much more that could help them find work on their release from prison. Yet – I am not making this up – the women spent their days sewing shrouds! Their learning opportunities amounted to a choice between hairdressing and beauty therapy, while the men were taught a variety of trades. I also felt that not enough attention was paid by the Government to the welfare of babies born to prisoners, or to the children in care while their mother was in prison, for a crime involving no violence. Defiantly, I ate into the front bench time. What did I care for this gentlemen’s agreement?

It was the same in the Chamber. On one occasion, we were hearing a report from the EU on workplace issues. Not one female backbencher was called. I complained to the Speaker, Jack Weatherill. He told me that, firstly, it was unwise to criticise any decision of the Speaker or his deputies. Secondly, ‘the ladies’ did not usually take an interest in these matters, and those Members who had been called had some involvement and had spoken on the subject in the past. So, I asked him, would they have to die before anyone else could get a look-in? And why did he think I was standing up trying to be called, over and over again for hours, if I was not taking an interest? He just said he understood my point but he couldn’t call everybody, and he tried to give everyone a fair crack over the weeks. He added with a smile, ‘One day many years from now, you may complain about letting these whipper-snappers into the debate, and your knowledge and wisdom left unheard.’ Yet I felt he was missing the point. There were so few women of any generation being heard, and we had perspectives on many issues that were not being paid attention.

I became so frustrated with this kind of casual sexism, especially where Scottish affairs were concerned, that I decided I would take it further. After all, the voters in Maryhill had sent me there. How were they supposed to know I was doing my damnedest to take part, and not shirking my responsibilities? So I gathered my evidence. I combed the columns in Hansard to prove how seldom I was called compared to my male colleagues. I told Donald Dewar that if matters did not improve, I would go public. Donald had no responsibility for any of this, but as leader of the Scottish group of Labour MPs, he had a lot of clout. I don’t know what he did, or to whom he spoke, but things definitely did get better.

There were times, of course, when we were more than happy simply to play a supporting role, such as the night we debated the Felixstowe Bill, a Tory plan to expand the docks there at the behest of P&O, who had newly acquired them. Would the company be paying for this work? No, don’t be daft. The taxpayers would. And why would the Government want to do their bidding? Maybe the fact that P&O contributed to Tory Party funds helped. T&GWU Members in particular were keen to oppose it, as it would cost jobs at other docks around our coast. It was also a matter of exposing corruption and misuse of the democratic process.

At that time you could still get away with filibustering. And this one was a beauty. Peter Hardy, Labour MP for Wentworth, raised a point that had not until then been considered: the threat to bird life if this upheaval went ahead. He knew, as a keen twitcher himself, that a particular bird – I cannot now remember what it was – would most probably be hugely disturbed and no longer nest in that area. This enabled the rest of us to keep him going with questions posed to him. Would this affect herons? How about robins? What of ducks and seagulls? And on, and on, affecting concern for just about every damned bird anyone had ever heard of in these isles. In answering our anxious questions in the affirmative or in the negative, and at considerable length, he even gave impressions of the songs of different species. How the Hansard writers coped with this I never discovered. We kept this up right through the night to breakfast time, thereby wrecking the next day’s timetable, while our colleague, maintaining a perfectly straight face, responded judicially and knowledgeably, until the Bill was talked out. The Tories were puce with rage. You can’t get away with that now. More’s the pity.

Then, later on, Parliament was televised. I voted enthusiastically for this reform, thinking the antics of some Members – sometimes so bad it would disgrace a primary one classroom – would have to stop if they knew their own constituents were observing how they behaved. Better still, the appallingly right wing views of some would be exposed. I had begun to realise that the parliamentary reporters, whether TV, radio, or nationals, were seldom interested in anything more than the front bench speeches that were handed to them in advance, so that all they had to do was check against delivery. The best a backbencher could usually hope for was a write-up in their local papers or an interview on local or regional radio and TV. Or you could grab attention by saying something way over the top. Then you got into the papers, no doubt about it, but your constituents thought you were off your head.