Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

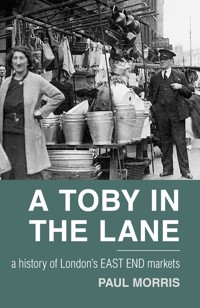

A Toby in the Lane reveals the rich fabric of the East End markets, primarily in Petticoat Lane and Brick Lane, and celebrates the street traders and stalls which call these London institutions home. This is the story of immigrant communities and their fight for survival, reflected in sweat and toil. Countless tales of traders' scams, tricks and banter are found inside. Families who have traded throughout the generations on the market offer up a unique insight into the layers of history that – up until now – have remained untold. The story also traces the sometimes complicated relationships between trader and authorities in an often amusing but informative tale of London market life. A spellbinding, quirky and intimate portrait of life on the famous markets of London's East End, written by an East End senior market inspector, A Toby in the Lane will delight Londoners and visitors alike.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 320

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title

Acknowledgements

Preface

Introduction

1 The Origins of Petticoat Lane

2 Tobys, Traders and the Market

3 Associated Markets

4 Brick Lane

5 Traders’ Tales

6 Reformation

Bibliography

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like firstly to express my appreciation to my wife Penny, without whose support and patience this book would not have been written, and to Costa, Sarah and other family members, for their encouragement and help. Many market traders have shown thoughtful generosity and enthusiasm during the course of this project: in particular, Munir Ahmed, Charlie Burns, Joe Barnett, Nej Fehmi, George Ozpembe, Terry Dervish, Pat Thorpe, Denise Brown, Alan Langley, Byron Thane, George Gladwell and John Calcutt. In the text that follows, some names have been changed to protect identities.

I am grateful to the library staff at Bishopsgate Institute, particularly Stefan Dickers, and at Tower Hamlets Archives, particularly Malcolm Barr-Hamilton, for their kindness, generosity and expertise. Many thanks are also due to the staff of the Jewish Museum, the Museum of London and the London Metropolitan Archives, with whose help I gained a great many insights and much knowledge.

Numerous others have helped enormously, including David Saunders, Phil Maxwell, Eugene McConville and Stephen Watts, donating their time and effort to this book in the form of remarkable photographs and narratives. My thanks go also to my colleagues and employees at Tower Hamlets Council. Last but not least, I am grateful to Michelle Tilling at The History Press for endorsing the project in the first place.

PREFACE

‘From poacher to gamekeeper’

Like many individuals in London I was not born in the capital, but came pursuing work, to explore and trial my ambitions. I was raised in the Lake District in Cumbria in exquisite rural surroundings that could be described as the antithesis to city life and, in particular, London. As a teenage lad, though, I had an early relationship with markets: my first job was working in the Cumbrian market town of Milnthorpe, assisting a market trader in setting up his shoe stall in the early hours of the morning before I went to school. I swiftly realised what a physically demanding job market trading was – and still is – but enjoyed the lively atmosphere and environment of the market. I had an additional job as a butcher’s assistant, where I learnt the essentials of trade and business.

My reason for leaving the North, however, was not markets but my passion for art. Following my ambition to paint and study I gained a place at art school in Cardiff. After my graduation in 1991 the inevitable move was to London to seek work and pursue an art career, but it soon became apparent that my art ‘career’ would not support me financially, even though I enjoyed some exhibiting success.

While continuing to paint I searched for job opportunities. For a short time I worked for the British Museum, which helped to ignite a love for history, but I soon realised that Portobello market, which was close to where I lived in Harlesden, in north-west London, provided the ideal opportunity for work. So, like many new immigrants to the city, I started my first job as a market trader in one of the most famous street markets in London. My stall sold second-hand clothes (labelled ‘designer’ before the popularity of the current ‘vintage’ label) that I procured from an auction house in Tooting that sold on lost luggage from London Transport and British Airways. Lacking a vehicle, I would pay for a taxi to deliver me and three or four large sacks of clothes that I hoped would bring financial reward to the market.

I soon recalled that the life of a market trader was not an easy one, and making money was a lot harder than I had imagined. My business enterprise was flawed: with little money to finance the business, no vehicle and little help I was doomed to failure. Nevertheless, I enjoyed the experience: the sense of independence, alongside the lively banter and intoxicating atmosphere of a bustling market, never left me.

For a few years afterwards I worked in enforcement jobs, including in the parking sector, while continuing to pursue a creative art career. The job in parking was, of course, that of a traffic warden and, while I was grateful for the work, it was a thankless occupation, stressful and demoralising. When the opportunity came up to apply for a position as a market inspector in Tower Hamlets I jumped at the chance. From 1996, when I started the appointment as the new market inspector, or ‘Toby’, I have not looked back. The environment of the market, its history, its characters and its day-to-day drama are enticing and addictive. A few years into the role, during a discussion about my personal history with my new manager David Saunders, an ex-army officer, he exclaimed with delight that since I had once been a market trader but was now a market inspector I had made the transition ‘from poacher to gamekeeper’.

This book presents a chronicle of two of the most significant markets of London, Brick Lane and Petticoat Lane, and their relationship with authority. The two markets are a 10-minute walk apart, lying in the heart of the East End between Aldgate and Bethnal Green, and their history is synonymous with the plight of the East End – its struggles with immigration and for social justice, its stoic endurance in difficult times and the contrast of present-day impending gentrification.

INTRODUCTION

London, in its first incarnation, was a trading post of the Roman Empire. The area was carefully chosen for its estuarine location, where the trade and distribution of goods could easily be maintained. In subsequent centuries, as London grew, street trading became its lifeblood, creating an unparalleled number of markets, each serving its own communities and each offering a different character.

In medieval times markets developed in popularity alongside fairs. The markets of Cheapside, Newgate and Smithfield strove to feed the ever-growing tastes of the London population, and it became apparent over time that markets required regulation. Laws were brought in not only to legalise the right to hold a market within a certain locality but also to protect the customer. The entitlement to hold a market was typically granted by a Royal Charter. Laws determining market hours were quite strict and those who traded outside market areas and times were heavily punished. Many of these regulations still have an influence today and, indeed, their principal aim of consumer protection is more relevant now than it has ever been.

Two momentous events in London’s history, the plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of London of 1666, changed the appearance of the city forever. Citizens who lived in suburbs outside the city’s gates were less affected by the latter event and, after a short period of time, there began a population explosion and property boom. The need for new trading areas became pressing as a result of an Act of Parliament of 1674 that banned street markets within the city walls and a growing populace in London’s growing suburbs, and it was not long before Petticoat Lane, just outside the walls, became perhaps the most important new market in London. With increased industrialisation in subsequent years the development of Brick Lane began.

These neighbouring markets would develop into the most famous street markets in London and, later, the world. They have been a cornerstone of London’s culture for over 400 years and continue to occupy a prominent place in the landscape and, indeed, in our aspirations and dreams. This book is about these two most important markets of London, both situated in the heart of the East End and within half a mile of each other. Petticoat Lane and Brick Lane are monuments to the culture of the city: they represent its beating heart that has kept its lifeblood flowing for generations. A city is as much about its people as its historical buildings, great paintings or museum artefacts, and there are no places more fascinating in London’s journey than these two markets, which have embodied so many different generations of London’s communities in all their aspects: hopes and struggles, riches and poverty, humour and sorrow, crime and degradation.

Bewildered as to why these markets had been largely excluded from history, like an unturned rock in a pool, I felt compelled to tell their story. The rich underbelly of life that they represent is an almost forgotten strand to London’s culture. John Marriott, in his book Beyond the Tower, describes Petticoat Lane as colourful, but notes that its ‘origins … are lost in time’. Although there are inevitably elements missing from the history, in this book I will trace as far as possible the rich historical narrative of the markets and bring to life their contemporary tale.

During my work within the markets as an official of the council, as a market inspector, or Toby, their varied and vibrant life has enthralled me. The tales of traders in the arena of the marketplace past and present are extraordinary. Often they are of a good-humoured nature, sometimes crude and explicit, sometimes sombre and affecting, but together they sum up the history of London’s immigrants over the many generations that have helped build the city, starting and making their lives within the markets of Petticoat Lane and Brick Lane.

These marketplaces have frequently been battlegrounds in which the radical, left-wing politics of the East End has been played out. They have seen the demands for better living conditions for impoverished immigrant communities; the rise of organised labour, where market traders formed their own organisations in a close reflection of the labour movement; and, of course, the battles between fascism and democracy.

In this book I will explore these themes, as well as the markets’ contemporary issues. The markets are now possibly facing their greatest ever challenge for survival as they pit themselves against the gleam and spit of modern shopping centres, parking challenges and gentrification – they are fighting to be a truly meaningful part of twenty-first-century London.

Paul Morris, 2014

1

THE ORIGINS OF PETTICOAT LANE

Petticoat Lane could once, justifiably, be called ‘world-famous’. Nearly twenty years ago, when I first encountered it, this was still the case. Now, however, it is somewhat diminished from that earlier status: such an assertion today seems an outdated claim to grandeur, given its present-day modest size and appearance. It remains a prominent feature of market life in London, however, and its history represents the very fabric and growth of London’s development, mirroring the enormous population explosion and expansion of one of the world’s greatest cities.

The history of the East End is inextricably tied up with its markets. Ancient markets such as Eastchepe have long since disappeared but Spitalfields, Roman Road, Bethnal Green, Watney Market, Chrisp Street, Columbia Road, Whitechapel and, of course, Brick Lane and Petticoat Lane very much continue to prosper, and it is evident that street trading has been instrumental to the development of the East End.

Hogge Lane

The earliest available historical references to the street now known as Petticoat Lane call it Berewards Lane. Berewards Lane dates back to at least 1218, when it was a track leading from Aldgate through fields to Bishopsgate and served as a shortcut to the Whitechapel Essex Road. It was located close to the walled City of London and as a consequence served as a popular route for farmers and visitors making their way to ‘Chepe’ markets within the city walls. Travellers often arrived too late at night, beyond the curfew bells, to be admitted to the city, and Berewards Lane thus became a convenient resting place.

The name Berewards Lane lasted until 1500, when it and land adjoining were sold by its monastic owners to farmers, who used it for the rearing of pigs. In John Stow’s survey of London in 1598 he notes the change of name that resulted, from ‘Berwards [sic]Lane … of olde time so called, but now Hogge lane’. Stow refers extensively to it in his survey:

This Hogge lane stretcheth North toward Saint Marie Spitle without Bishopsgate, and within these fortie yeares, had on both sides fayre hedgerowes of Elme trees, with Bridges and easie stiles to passe ouer into the pleasant fieldes, very commodious for Citizens therein to walke, shoote, and otherwise to recreate and refresh their dulled spirites in the sweete and wholesome ayre, which is nowe within few yeares made a continuall building throughout, of Garden houses, and small Cottages; and the fields on either side be turned into Garden plottes, teynter yardes, Bowling Allyes, and such like, from Houndes ditch in the West, so farre as white Chappell, and further towards the East.

The pig farming proved particularly successful, as its close proximity to the food market of Eastcheap (distinguished from Cheapside, which was in the west of the city) meant that fresh meat could be easily transported out to customers, giving an advantage over traders from further afield. As the pig-rearing enterprises flourished they began to attract other tradesmen and craftsmen to the area, developing the vicinity into an important area for commerce. Such places were increasingly important for the growing city. The population within the city walls by the year 1500 was no more than 75,000, the Black Death and other plagues having limited population growth, but during the next century expansion was enormous and by 1600 London’s populace was 400,000. Parishes outside the city walls, such as Whitechapel and Shoreditch, underwent enormous increases in population, providing a spur to the development of the nascent markets.

Map of Spitalfields, 1560. (Courtesy of Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives)

Elizabethan map. (Courtesy of Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives)

The development of Spitalfields

After Henry VIII’s break with Rome in the mid-sixteenth century land owned by monasteries and abbeys became available to lease for property speculators. The area later known as Spitalfields, after the hospital of St Mary of Spittal, which during the medieval period had catered for the sick and the poor, would come to play an important part in the expansion of the markets of Petticoat Lane and Brick Lane, and the surrounding area.

The significance of Spitalfields’ association with Petticoat Lane cannot be underestimated. Spitalfields market was granted a licence by Charles I in 1638 but deteriorated until 1682, when Charles II granted a Royal Charter to John Balch, a silk thrower who married Katherine Wheeler, daughter of market trustee William Wheeler,1 giving Balch the right to hold a market on Thursdays and Saturdays in the area of Spitalfields or its close proximity. This development was in response, of course, to the need to feed an ever-growing population in the area. Unfortunately John Balch died a year later and did not see his plans develop, but, fortunately for the future development of the area, he left the leasehold and market franchise to Edward Metcalf, who wasted no time in creating a permanent building to be used for market purposes.

Soon after the market was established Metcalf also unfortunately died and the lease was taken over by a trader from the City of London named George Bohun, who saw the potential in supplying the increasing population of the city with fresh fruit, vegetables and meat. The market soon became imperative to the stability of the community and was, indeed, London’s most significant fruit and vegetable market at this time.

By the early 1700s the market was thriving and would soon be home to the area’s second wave of immigration, the French Huguenots, who had fled France following religious persecution. French Huguenots, who were Protestants, had enjoyed the protection of their civil rights under the Edict of Nantes but these freedoms were repealed by Louis XIV, who tried to force conversion through repression. Up to 50,000 people fled as a result and came to London. It was at this time that the French word ‘refugee’ entered the English language.

The Huguenots were attracted to the area of Spitalfields because it had already been settled, over a century earlier, by Dutch and French silk weavers who had taken advantage of the area’s close proximity to the city to expand their trade. The existence of a familiar and sympathetic community enticed the new wave of French Protestants, of whom a large majority practiced silk weaving. The silk weavers would tenter out their wet silk by means of hooks to prevent shrinkage in the spittal fields, giving the area a distinct identity. We are reminded of their presence today in so many ways and their influence upon the vicinity of Spitalfields cannot be understated – from houses built at the time (for example, in Fournier Street, Folgate Street, Princelet Street and Fashion Street, now the residences of artists such as Gilbert and George) to the language of the Huguenots, which has left its physical imprint on the area in place names such as Tenter Lane, which still leads from Spitalfields market. Indeed, at this time the area was known as Petty France. Their skills and expertise in silk weaving, alongside other trades and interest in arts, made the Huguenots into a distinct and successful community. They also engaged in many intellectual pursuits: historical and mathematical societies and interests in botany and music were very popular.

The Huguenots would soon be put under enormous pressure, however, when Irish immigrants began to arrive in the mid-1700s. Not only were these new settlers adept at weaving, but they were able to undercut the Huguenots in terms of wages and conditions of work, making cheaper alternatives. Tensions grew between the communities, culminating in riots in 1736 during which Irish businesses and homes were attacked by the Huguenots. Poor relations, poverty and a disgruntled workforce continued for many years until, in 1762, the Huguenot journeymen agreed a set of wage and work standards with their masters in an attempt to secure living wages. However, these standards were again undercut and renewed disorder characterised the period from 1769 to the mid-1770s. Peace finally broke out in 1773 when the first Spitalfields Act was passed to regulate working conditions and wages.

Although there was relative calm thereafter, the weavers’ industry had gone into decline, partially as a consequence of the workings of the Spitalfields Acts, which were repealed in 1824. Subsequently attempts were made to preserve the silk-weaving industry, with a few companies remaining in the area. As late as 1900 an employee of one of these companies, George Dorcee, attempted to support the industry by appealing to the local authority against the demolition of weavers’ houses. Incredibly, he succeeded, prolonging the industry for a few more years, but, perhaps more significantly for the area, also preserving its homes. By this time, however, the decline was terminal, leaving many weavers in poverty, and the Huguenot community was dispersed. Many weavers sought new employment within the docks or became market traders in the growing areas of Petticoat Lane and, ironically, the food market that had been established around the Spitalfields hospital site.

The impact of this food market in the area may often be understated but was in fact enormous. It served not only the Huguenot community but also the traders and costermongers of Petticoat Lane for over 200 years. Initially trading was conducted from a collection of sheds and stalls but, with London’s growing appetite for fresh fruit and vegetables, it was in desperate need of modernisation by the mid-1800s. The market in its present form was finally rebuilt by former market porter Robert Hormer in 1888 after he had purchased the lease two years earlier and was run by the City of London; it then continued to serve for another 100 years as a wholesale fruit and vegetable market. Wholesale trade at Spitalfields ceased in 1991, after which it was left unused until redevelopment in 2005. The market was fully restored in 2008, with a Norman Foster-designed office block at its western end. It is now a beacon for artisan trade and plays an important role between the continuing street markets of Petticoat Lane and Brick Lane, attracting young artists and designers. It is instrumental in the regeneration of the area.

Lamb Street, Spitalfields market, 1912. (Courtesy of Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives)

Petticoat Lane

An important figure in the development of Hogge Lane was Benedict Spinola (1520–1580), an Italian merchant who leased ground there in the late 1500s.2 He developed cottage housing for the poor and larger houses for the rich, building up to 100 homes. More and more foreign visitors were coming to London, but they were frequently met with resistance and, indeed, riots; Hogge Lane soon became a very popular place to trade, becoming a refuge for many who took the opportunity, often out of necessity, to develop an occupation in trade. Moreover, in around 1606 the Common Council passed an Act in response to the great number of foreign street hawkers that said: ‘That no foreigner whatsoever should presume to vend his, her or their goods in the city, by connivance or otherwise, either in shop, house, stall or street upon the penalty of £5 for every offence except such as brought provisions to the city.’ The huge fine had the desired effect and drove the hawkers, who sold mostly second-hand clothes, out of the city and into Hogge Lane, which was soon renamed Petticoat Lane, appearing for the first time as such on Ryther’s early seventeenth-century map of London.

At around the same time a further reference to the new name occurs in Ben Jonson’s play The Devil is an Ass (1616):

Like a needle of Spain, with a thread at my tail

We will survey the suburbs and make forth our sallies,

Down Petticoat Lane and up the smock alleys,

To Shoreditch, Whitechapel and so to St. Kathern’s,

To drink with the Dutch there, and take forth their patterns.

(Act 1, Scene 1)

At this time in the seventeenth century Petticoat Lane was a desirable area, according to the ecclesiastical historian John Strype, the son of John Strype (or van Strijp), who had come to London to learn the business of silk ‘throwster’ from his uncle Abraham van Strijp, of Dutch nationality, who, to escape religious persecution, had taken refuge in England. He, like many early settlers, was Jewish. Strype later set up business for himself in what was later known as Strypes Yard – now Strype Street – which forms part of the Petticoat Lane market that still operates to this day.

Strype’s references to ‘Petticoat Lane’ suggest a place where some gentleman of the court and city had their town houses. The most notable of these was the Spanish ambassador Hans Jacobson, jeweller to King James I. However, the gentrification of the area did not last long. In 1665 the bubonic plague struck and in the following year the Great Fire of London devastated the city. The map of London was about to be redrawn. New areas were sought for settlement and business opportunities, and cheaper housing became available. As a consequence of the rebuilding of the city Petticoat Lane became populated by impoverished workmen who needed to live close by their work, and so very crowded streets of small houses were built in the area. The increase of population necessitated the development of new street markets. Furthermore, an Act of Parliament of 1674 banned street markets within the city walls and, within a short time, Petticoat Lane became the most sought-after area for further development in market trading. The market, which developed to serve a growing number of immigrants and the existing poor, affected the social standing of the area and houses once populated by the rich were taken over by businessmen and immigrants who began to trade there.

As noted earlier, the area then received a significant immigrant influx of approximately 13,500 French Protestants fleeing from religious persecution following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. A great number of these immigrants were silk weavers who were extremely skilled at their work, but even with these new skilled workers Strype still implies that the area had lost its social standing. As discussed previously, the arrival of the French Huguenots was crucial to the development of the fabric in the area and in particular to Petticoat Lane. It is with these changes that, by the next century, the shape of Petticoat Lane market as we know it today had truly come into being.

Ghetto in the ‘Lane’

The Lane was always the great marketplace, and every insalubrious street and alley abutting on it was covered with the overflowing of its commerce and its mud. Wentworth Street and Goulston Street were the chief branches, and in festival times the latter was a pandemonium of caged poultry, clucking and quacking and cackling and screaming. Fowls and geese and ducks were bought alive, and taken to have their throats cut for a fee by the official slaughterer. At Purim a gaiety, as of the Roman carnival, enlivened the swampy Wentworth Street, and brought a smile onto the unwashed face of the pavement.

Especially was this so at Passover, when for a week the poorest Jew must use a supplementary set of crockery and kitchen utensils. A babel of sound, audible for several streets around, denoted Market Day in Petticoat Lane, and the pavements were blocked by serried crowds going both ways at once. (Zangwill 1892)

During the 1700s the area was extremely shabby but well known as a district that anybody who had anything to sell would visit for that purpose. Jewish peasants from central Eastern Europe began to settle in the area, but found it extremely difficult to find employment because of their curious looks, their unusual religious practices – with Sabbath hours and holy days conflicting with those of the indigenous population – and, of course, the language barrier. The Jewish immigrants’ salvation was thus Petticoat Lane market, where they sold whatever they could, almost inevitably second-hand clothes, to make ends meet. They carried out their sales partly in Yiddish and partly in cockney, slowly integrating into life on the market. Women found such occupation a particularly useful opportunity to earn a wage supplementing the family income.

The deterioration in the status of the area seems to have continued and was marked by levels of crime and disorder. For example, in 1747 the General Evening News reported that the master of the ‘Cock Alehouse’ in Petticoat Lane was tried at the Guildhall for keeping a disorderly house. Prostitution and the ‘fencing’ of stolen goods in public houses around the market were commonplace. Other newspaper reports from the time refer to ‘gangs of robbers keeping the inhabitants in continual fear’. One such report, from 1775, reported that ‘There is a gang of robbers about Petticoat Lane and its vicinity not much less daring than the Black boy-alley gang, of infamous memory, who keep the inhabitants in continual dread.’ Another report refers to ‘Martha Cutler, Sarah Cowden and Sarah Storer for feloniously assaulting Henry Soloman in the dwelling house of Aaron Davis in Petticoat Lane, Dilings in Gun Court, Petticoat Lane and robbing him of £15 4s in money’. In 1787 the situation was so bad that the parish of Whitechapel had to appoint day and night patrols in the Lane and surrounding areas to protect its population.

Life in Petticoat Lane. (Courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute)

Petticoat Lane on a Sunday morning. (Courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute)

The market continued to flourish in spite of – or perhaps because of – the poverty and degradation in the area. Although the Huguenot silk weaving trade was to enter a terminal decline with the Anglo-French free trade treaty of 1860, which allowed for the import of cheap French silk, the area was to develop in other ways. The Jewish refugees took advantage of the Huguenot houses as their dwellings and found their large windows eminently suitable for tailoring. Jewish and other immigrants also developed other craft and manufacturing trades, such as furniture making, but the markets of Petticoat Lane and Brick Lane ensured, in the flourishing of street trading, occupations for the many that did not possess such lucrative skills.

Exodus empire

The course of the nineteenth century saw a further enormous rise in the immigrant population, with many more Russian and East European Jews fleeing persecution, alongside Irish immigrants escaping the potato famine. Many of these immigrants settled in the East End and the ‘Lanes’ provided both a means of gaining an income and strong community bonds.

The area had a large Jewish population and the market has been associated with Jews from its inception. Because of the Sabbath, Sunday eventually became the main market trading day. The area was, as noted, extremely deprived and new immigrants who were half starving were helped by wealthy West End Jews, who set up various institutions to help its population, including soup kitchens and the Jewish Free School. Established in 1820, the Jewish Free School was originally built to house 900 pupils, but by 1907 had become the largest elementary school in the world, with more than 3,500 pupils. Alumni include the entertainer Bud Flanagan OBE and the diamond millionaire Barney Barnato. The Jewish Board of Guardians was also established. These organisations made a significant difference to the lives of many Jewish immigrants.

Aside from Jewish organisations, other philanthropists and organisations mobilised in the East End to help the poor and destitute. William Booth’s Salvation Army developed from his Christian Revival Society, which was set up in 1865. Booth, who abandoned the Church for preaching the gospel on the streets, sought to ‘rescue’ drug addicts, alcoholics, prostitutes and the homeless through religious conversion and membership of his Christian army.

Despite these private philanthropic efforts, however, Petticoat Lane was a matter of deep concern to the authorities, its somewhat infamous reputation being seen as problematic. In an effort to try and get rid of the market they changed the street’s name from Petticoat Lane to Middlesex Street (the street was at that time in the County of Middlesex) in 1830. This was also seen as a way of excising an embarrassing reference to a female undergarment. The new name was ignored by the East End inhabitants, however, who continued to refer to the market as Petticoat Lane. Much to the dissatisfaction of the authorities the market, far from disappearing with the name change, continued to expand and grew yet more popular.

Petticoat Lane was an area of shops and street traders. Half of all shops by 1850 sold new or second-hand clothing. Henry Mayhew, in his book London Labour and the London Poor, wrote:

Embracing the streets and adjacent to Petticoat Lane and including rows of old boots on the ground there is between two and three miles of old clothes. Petticoat Lane proper is long and narrow and to look down it is to look down a vista of many coloured garments. These things, mixed with the hues of the women’s garments, spotted and stripped [sic] certainly present a scheme which cannot be beheld in any other part of the greatest city in the world, nor in any other portion of the world itself.

Another valuable insight into Petticoat Lane in the mid-1800s is contained in Watts Philips’ book The Wild Tribes of London. He relates the familiar accounts of criminal activity, notably the ‘fencing’ of stolen goods, and notes that, in the Lane, one is ‘surrounded by thieves on all sides’. Although, of course, these reports add to the market’s disreputable image, in another passage he describes the market in extraordinary terms, conjuring up a place that must have filled and intoxicated the senses:

Here, also are merchants from Smyma and Constantinople, dealers from Hamburgh, Frankfort and a host of towns beside; two Russian Jews from Siberia and one shrivelled little monkey-faced Hebrew from Morrocco. They are speaking languages of all kinds … And we look upon men who have travelled from all corners of the earth to trade and to trade in Petticoat Lane.

Petticoat Lane’s reputation, despite its importance to and popularity among the local community, continued to be derided in the press. For example, in The City Press of 20 August 1881 an article describes:

… the market [as] one of the curiosities of London. As a lively and literal picture of low life it is not to be surpassed and for students of certain phases of metropolitan existence it possesses a peculiar fascination … The sellers in expatiating on the value of their goods, employ figures of speech which are apt to jar upon polite ears … From end to end the street is packed with [a] noisy, sweltering mob, Jew and gentile herding together indiscriminately, and the distinctions of race seeming to blend in a mass of uniform ugliness.

The Lane would receive further notoriety on 30 September 1888, when Catherine Eddowes was killed in Mitre Square, a short distance from Petticoat Lane. Her garments were torn and a part of them was found in Goulston Street (an area of Petticoat Lane market); on the wall above was graffiti: ‘The Juwes are not the men that will be blamed for nothing.’ This incident has since become part of the Jack the Ripper mythology and theories abound regarding its meaning, but there can be no mistaking that the message linked the murders to the local Jewish community. It is not known whether the blame attaches to a person from another community who used the Jews as a scapegoat or whether the culprit was of Jewish origin but, of course, the murder only cemented the view that the area, including the market, was nothing more than a den of iniquity.

Alongside the market’s reputation as a place of thieves, shabbiness and unholy alliances was a stereotypical perception on the part of the public of Jews as scrooges and swindlers. It was clear, though, that the Jewish community was at pains to assimilate and be accepted into British society, despite a growing tide of discrimination. Although the market was a place of lawlessness it remained an intrinsic part of the immigrant community simply because poverty was the great leveller and the market provided the means and mechanisms to navigate survival.

An example of the importance of the market to immigrant communities was Leyden Street, where there are now decaying and boarded-up Victorian toilets. It was once the area where the Jewish community would debate politics and current events, and was widely known as the Parliament of Petticoat Lane. Leyden Street is not the street it was and I recall that, only a few years ago, when the toilets were open to the public, it was plagued by anti-social behaviour, drug use, prostitution and ‘cottaging’. In fact, for a short time market officers were instructed to patrol and root out any disreputable behaviour. This was a task dreaded by the officers but made slightly more amusing by one of the elder Jewish female traders on the market, Karen Goldman, who would bellow down into the toilet basement ‘Cocks in, trousers up!’ Leyden Street is now undergoing refurbishment, and smart new apartments are being built around the site.

In the areas surrounding the market people of various ethnicities tended to live in their own community ‘pockets’, in particular the Irish community, who lived in and around the notorious Dorset Street, the poorest street of London, renowned for being ‘the worst street in London’. Russian and East European Jews lived in their own hierarchical communities in other areas surrounding Petticoat Lane. In attempting to overcome the many distressing problems of crime and poverty, the various immigrant communities looked to the market of Petticoat Lane for a chance to progress from abject poverty and deprivation. Different nationalities traded side-by-side in an enduring struggle for subsistence in the biggest open market sprawl in the world.

Sunday market, Petticoat Lane, c.1890. (Courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute)

A typical scene in Petticoat Lane, c.1910. (Courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute)

The particular themes of poverty, crime and politics, and the market’s growth into the twentieth century, I shall explore in more detail below. It was clear, however, that at the end of the nineteenth century Petticoat Lane was destined to play a significant part in London’s development and, in particular, in the expansion of population and economic growth in the East End.

Lawlessness and poverty

The growth of Petticoat Lane was a cause for grave concern in Victorian society. This lawless area, populated by immigrants, was ostensibly out of control. The authorities had tried unsuccessfully to manage the area: newspaper reports show that from the middle of the 1800s the police tried to put an end to the ‘Petticoat Lane nuisance’, after many complaints had been made. However, this had little effect on the Jewish traders, who ‘continued their business within the mart as usual’.

The Petticoat Lane market can be imagined as a lifebelt for the drowning poor, as a place where there was a chance to make a living and to avoid succumbing to prostitution and homelessness. The marketplace became a great cultural leveller, with all plying for trade side by side. The traders of Petticoat Lane were an unusual, strong and independent force bonded by poverty – but, as a haven for the poor, the market was also attractive to the dark criminal underbelly of London.

The Jewish immigrant in particular gained a reputation for criminality and undesirable activity. There were many reasons for this perception, which was not always unjustified. But, as the website Moving Here (www.movinghere.org.uk) suggests, ‘Jews were more or less forced to cluster in insecure occupations where there was a narrow borderline between straight and improper practice’. The Jewish population were forced to live by their wits, as were the other immigrant communities, as they were often excluded from more respectable jobs. It is no wonder that various criminal and underworld practices were adopted as means of survival. The marketplace could thus be not only the buffer zone between an immigrant and abject poverty but also an arena of undesirable activity.

As early as the mid-1800s, Petticoat Lane’s notoriety came to the attention of Parliament, and, in an extensive article published in The Builder