Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

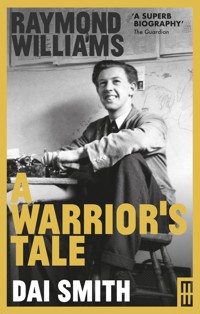

RAYMOND WILLIAMS (1921-1998) was the most influential socialist writer and thinker in post-war Britain. Now, for the first time, making full use of Williams's private and unpublished papers and by placing him in a wide social and cultural landscape, Dai Smith, in this highly original and much praised biography, uncovers how Williams's life to 1961 is an explanation of his immense intellectual achievement.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 948

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

RAYMOND WILLIAMS

A WARRIOR’S TALE

DAI SMITH

5

For Norette6

Preface

The book that follows leaves its subject, Raymond Williams, in 1961 on the threshold of a public career as writer and intellectual which resounded across the world. It was in that year, 1961, that I was first made aware of his name when the shiny blue Pelican paperback of Culture and Society, his breakthrough book of 1958, slid across my desk in Barry Grammar School. It came, as did most of my challenging reading matter in those days, courtesy of a history teacher of care and genius, Teifion Phillips. Teifion had firm socialist convictions and an equally firm belief in spotting potential talent wherever he found it, in or out of school, and of whatever kind it was. Mine was deemed to be academic, and a working-class home was to be no barrier to university entry, even to Oxford where Teifion’s links, though I scarcely knew it at the time, were to Balliol, forged by the summer schools he had attended there in the early 1950s. A conveyor belt for undergraduate historians from South Wales had been duly installed.

It is entirely possible that Teifion had met Raymond at one of these W.E.A./Extra-Mural summer schools but if he did he never mentioned it to me. The purpose in giving the paperback to the intellectually rapacious sixteen-year-old was to fill out the standard Sixth Form fodder with a richer diet of debate and argument beyond factual retention and the rote imbibing of then-current controversies on the interaction, or not, of Protestantism and Capitalism, or the Rise, or not, of the Gentry in those interminable, or it so seemed to us, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Raymond Williams entered my life – well almost so – as light relief.

What, of course, captivated me, and many more like me across Britain in the 1960s, was not, at first, Williams’ re-examination of the cultural critique that followed on industrialisation, but his emotional and personal account of what it actually and inwardly, personally and familially, individually and publicly, meant to be a handpicked “Scholarship Boy” and, more, what it implied socially and culturally. I vividly remember being both acutely stimulated and deeply shaken as I read his thunderous “Conclusion” to Culture and Society, a book whose viiispecific essays had only clung to my mind like burrs that had floated by and stuck, to be picked off and examined at some later date.

For my generation, subsequently, both the detail of his later work and its ever-widening compass became a constant challenge to grow and, in its shape and focus, a resolute reminder of what was to be valued, but radically so, as root for the keyword and actuality of community. His almost weekly book reviews in The Guardian whetted the appetite to see how the journalistically compressed and gnomic might become extended by illustration and explanation into yet another strikingly new direction. The books indeed followed. There is no denying that more than a tinge of hero worship – anathema to him – was directed his way and perhaps to a greater extent by those of us learning from him from afar than by those he was teaching close-up in Cambridge. Sometimes, it seems, that personal acquaintance could be an unhappy one as it became clear that his own priorities and needs were not always, or not often enough, those of some predatory undergraduates. There were numbers more, however, who testify to the care and attention he gave in their undergraduate and graduate years. All who encountered him, in person or in his work, agreed on one thing: that whether you like it or not, that work and his life experience were inseparable.

I first met Raymond Williams in 1976. The circumstances verged on the comic and were quite typical of him. Llafur, the Society for the Study of Welsh Labour History, of whose journal I was then editor, had invited him to speak at a conference on the fiftieth anniversary of the General Strike. It was to be held on the hillside campus of the Polytechnic of Wales, now the University of Glamorgan, at Pontypridd. In those days, in the wake of the 1972 and 1974 miners’ strikes, the National Union of Mineworkers, especially in South Wales, was not only militant in action, it was intensely conscious of its own past endeavours over sixty years in the provision of cultural and educational initiatives for its members. A strong revival in those activities in the early 1970s ensured that, in addition to academic and local historians, the conference was attended by a few hundred working miners and union officials. It was exactly the kind of mix and occasion he would relish.ix

Only, Raymond, who was scheduled to speak after the mid-morning coffee break on the Saturday of a three-day event, had not appeared. We fanned out to man the Poly’s scattered entrances, armed only with the vague memory of a dust jacket photograph and the helpful thought offered by some committee member that he would surely be driving “a big car”. Two minutes before the appointed hour I returned, disconsolate, to the lecture theatre to be met by Kim Howells, a Warwick PhD student at the time, but one resident in Cambridge and often in attendance at university seminars when Raymond had been present. I glumly gave him the news. Puzzled, he said, “But there he is”, and pointed as a man in his mid-50s rose from the middle of the raked and assembled audience to make his way down to the front. He had been there all morning, unobtrusive and unannounced, himself a part of a congregation whose connections, cultural and historical, he so much respected. He spoke, with no discernible notes and the utmost lucidity, for almost an hour, and later, as editor, I received the paper he had written up from his tape-recorded ruminations and published it as The Social Significance of 1926.

Thereafter, I lectured on some of his Cambridge courses at his invitation and I chaired him on other occasions or discussed his fiction with him at public meetings on his increasingly frequent visits to Wales. By the time of his early death, in 1988, I could feel myself to be a friend as well as a continuing admirer. So, when Joy Williams, a short time after his funeral, asked me if I would like to consider writing a biography, my instant answer was “Yes”, despite other commitments that would require shuffling and the reservation I had about writing a Life that seemed to me, then, to be necessarily a life of the mind more than anything else. But, like so many others then and since, I was naturally enough looking through a telescope that seemed shuttered until the full opening of 1961 and his return to Cambridge as a Don and the notorious author of The Long Revolution, a work more startlingly iconoclastic than Culture and Society.

What became clear to me, very quickly and very unexpectedly, was how my perspective would need to shift from the somewhat conventional xbiography I had had in view and how daunting that shift appeared when I first considered the materials which Joy Williams rather hesitantly placed before me. That happened after some preliminary one-to-one interviews with Joy, first in their family home at Craswall and then in the house in Saffron Walden to which she and Raymond had moved upon his retirement from Cambridge. I had kept enquiring about letters, diaries, manuscripts, anything really beyond the published works and the list of people to see which I was already accumulating; it was the historian’s desire for what is tangential rather than the critic’s need for what is central. Late one afternoon, somewhat reluctantly, Joy took me down into the basement of the house and indicated a large and battered white cabin trunk. She warned me that there was no order to anything and that his normal response over the years had been to throw things away or shuffle them off in piles into some corner or other. The trunk had become the principal depository of all this sloughing off.

I opened the lid, delved in and began to take things out. Over the next two hours or so I saw that I was confronted by exercise books full of juvenilia; reams of pencilled and inked manuscript that seemed to be anything from stories to essays to schemes for writing; carbon flimsies and typed copy of unpublished short fiction; mounds of unpaginated and mixed extracts from lengthier fiction; the titled and bound files of novels he had mentioned in Politics and Letters (the interviews of 1979) but had then discarded or failed to publish; plus various and confusing versions, hardly any of them sequential, of what became Border Country; the dusty note diaries of his father; a typed-up War Diary or Memoir of his own; single sheets of plots or charts of fictional characters; doodled sketches and passages marked in early books from school; and a couple of pocket maroon-coloured Notebooks with hard covers and with his 1950’s address in Hastings inscribed against loss on the inside. And that was only the stuff before the 1960s with other “finds” from Joy – wartime letters, obscure magazine articles, early correspondence with friends and colleagues, photographs – to come over the following months. My research work, soon xiaccelerated by the award of a Simon Senior Fellowship from the University of Manchester for 1992-93, proceeded. I did not, at this stage, decide that a single volume would need to be written just to do justice to this material because I did not then fully understand how vital it was to a complete understanding of Williams’ life and work. I did, though, know that it was going to be a long haul.

How long is another matter, and for all involved – but especially for my wife and family – as I sometimes wondered if I would, or could, ever get to a finishing line, I can only hope that the outcome proves worth the long simmer. I was on the boil by 1993 for sure, but unexpected and labour-intensive career shifts in BBC Wales and then at the University of Glamorgan, along with the displacement activity of other writing which required shorter bursts of time and concentration, meant I did not really turn up the heat again until the University of Wales, Swansea appointed me to a Research Chair in the Centre for Research into the English Literature and Language of Wales in March 2005, so allowing me to write this book in the way and in the shape I now envisaged. That is my latest debt and this book is its principal repayment.

My other debts, early and late, are as appreciated and as deeply acknowledged to individuals and to institutions. Amongst the latter, in addition to Swansea University where the Raymond Williams Papers are now deposited and are awaiting a full catalogue for scholarly use, I would like to thank Cardiff University where I held a Chair in the History of Wales from 1985 and which gave me leave to hold the Fellowship granted by the University of Manchester in 1992-93, and where Huw Beynon in Sociology gave me a Welsh welcome. The British Academy assisted me that year, for travel and research purposes, with one of its invaluable Small Grant Awards and I used it to research the Chatto and Windus Archive of the University of Reading; the Imperial War Museum’s collection of letters of the Second World War; the Records of the External Studies Department at Oxford; the BBC’s Written Archive at Caversham, where Joanne Cayford was particularly helpful; the P.R.O. for War Diaries; and the Old Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, where Brigadier Timbers proved an invaluable and friendly aid to a tyro xii“military” historian. Andrew Green, Librarian at the National Library of Wales which houses another, smaller but complementary batch of Raymond Williams material, ensured that I was able to piece together a few missing bits of a fictional jigsaw (the parts of the early unpublished novel, Brynllwyd), and both Sir Adrian Webb, then Vice-Chancellor at the University of Glamorgan, and Geraint Talfan Davies, Controller BBC Wales, were invariably sympathetic (up to a point, of course!) to my authorial frustrations when I worked in those institutions between 1993 and 2000.

Individuals, in the end as in the beginning, were the real catalysts in the thought and in the writing. My principal debt is to the late Joy Williams who was utterly generous with her own time, unfailingly frank and, with no caveats, willing to give me unfettered access to and use of her husband’s papers. It is true of many of his books that they would not have existed in the shape we have them, and some not at all, without Joy Williams’ commitment and contribution. I am proud to say that this is now also true of my own present book.

To Merryn Williams, and to Ederyn and Madawc, I am profoundly grateful for their long and understanding patience with me and to Merryn, in particular, for sharing her own researches on her family which I pursued further, in Pandy, with the help of Raymond’s sister-in-law, Sylvia Bird. Other family members who helped me with memories of his upbringing, especially of his mother, were Winifred Fawkes and his cousin Ray Fawkes, whose marvellous sketch map adorns the inside covers. Correspondence with Brinley Griffiths and his brother Maelor Griffiths, Raymond’s close friend of the pre-war years, was as inspiring as it was revelatory. I owe them deep thanks.

And at Pandy and Abergavenny I garnered a great deal in interviews with Joan Leach, Albert Lyons, Lew Griffiths, Violet James, Bill Berglund, Illtyd Harrington, Dick Merton-Jones and Gwyn Jones. I was delighted to be able to trace and correspond with Raymond’s Yorkshire friend of those years, Margaret Davies neé Fallas, who provided insights and photographs. For his early Cambridge years I talked to Lionel Elvin, corresponded with Muriel Bradbrook and interviewed his close friend, xiiiMichael Orrom, whose own film and associated memoir were more than a boon. So too were the memories and diary I was privileged to make use of by Lady Anne Piper neé Richmond.

In the Gower I found and talked to Eddie Gibbs who served under Raymond Williams’ command in the War and, for the Cambridge years thereafter, Wolf Mankowitz was forthright, disarming and charming. I spoke with Raymond’s Adult Education colleagues in the Oxford Extra-Mural Delegacy, Arthur Marsh and Jack Woolford, as well as with his contemporary and friend, Tom Thomas, a legendary and inspiring Extra-Mural Literature Tutor at Swansea. Annette Lees neé Hughes helped with memories of the newly-married Joy and Raymond, and Eric Hobsbawm shed a direct light on both the Cambridge Left and the postwar settling in of their generation.

For the 1950s, especially concerning the marginality and then the centrality of Raymond Williams first to the Communist left and then to the political culture of the New Left, I am indebted to conversations with E.P. Thompson, Raphael Samuel, Graham Martin and Stuart Hall; and, for some subsequent reflections, to Lawrence Goldman, Terry Eagleton, Robin Blackburn and Robin Gable. Members of Parliament can be hospitable and sometimes good listeners to an obsessed author, as Kim Howells MP and Paul Murphy MP proved to be more than once. Still in a Parliamentary vein, though he had not then been elected as the Member for Aberavon, my oldest friend in all these related endeavours and much else, Hywel Francis, proved as supportive as only he can be when he was Professor of Adult Continuing Education at Swansea University.

More recently at that University support has come in no small measure from its far-seeing Vice-Chancellor, Professor Richard Davies, and from Professor M. Wynn Thomas, Director of CREW, who read and commented with critical attention on early drafts, as did his and my colleague in CREW, Dr Daniel Williams, whose own work will take our understanding of Raymond Williams forward. Other readers who have chivvied, urged and instructed me to put drafts into better shape were my former student Rob Humphreys, now Director of the Open University in Wales; Dr Steve Woodhams of Thames University; Dr Hywel Dix xivat the University of Glamorgan, and Professor John McIlroy of Keele University. Steve Woodhams deserves a double thanks for his care and his help in locating material, especially pamphlets, and for sharing in and often challenging my wilder speculations.

Along the way it was a pleasure to work with Colin Thomas whose BBC 4 film on Raymond Williams, ‘Border Crossing’, to which I contributed and acted as consultant, won the Jury Award at the 2005 Celtic Film Festival. It was a pleasure, too, to help Richard Davies of Parthian bring Border Country back into print in 2005 as the first volume in the Welsh Assembly Government-inspired Library of Wales Series. At the proof stage the book came into its own as a “Welsh European” – Williams’ late and accurate self-description – when Martine Jousset fielded and ferried batches of e-mails to me in the Languedoc, at Nébian.

I am grateful to a brilliant Personal Assistant at BBC Wales, Ann Harris, for typing up early sections of first drafts and, as with so many others, putting up with my discontents. At Parthian, Jasmine Donahaye has proved a masterly and inspiring editor at a late stage and working to impossible deadlines: she combines meticulousness with sensitivity in a way that has vastly improved successive drafts and I owe her a great deal of gratitude. As I do to the proof-reading of Paul Duerden and the typesetting of my friend John Tomlinson who have also ensured that the Index was as meticulous as the rest of their endeavours. Finally, two people alone are responsible for ensuring the book took shape at all. The first is my indefatigable and uncomplaining word processor, as I’m told typists are now known; she is also known as my former and exceptional Personal Assistant at the University of Glamorgan, Gwyneth Speller, and quite how she deciphered, corrected and produced readable typescript from acres of pencilled yellow pad remains a mystery for whose solution I am deeply grateful.

And ultimately there was at the beginning as there is at the end, Norette, without whom there would really have been no book at all.

Dai Smith Barry Island; Nébian spring/summer 2007

Contents

List of illustrations

1. Joseph and Margaret Williams, his paternal Grandparents, buying fish. 1890s.

2. Harry Williams, seated, France, 1917.

3. Raymond Williams seated on far right, Pandy School, mid 1920s.

4. Harry Williams, Raymond and the bee-hive, the summer of 1926.

5. Harry Williams, late 1920s in Pandy, at his garden gate.

6. Raymond Williams seated on far left, Pandy School, mid 1920s.

7. Raymond and his mother, Gwen, in 1930 on a holiday in Teignmouth.

8. Gwen in the doorway of Llwyn Derw, Pandy late 1930s.

9. Raymond at Pandy station, mid-1930s.

10. Raymond in Harry’s vegetable patch, 1936.

11. The train from Abergavenny towards Hereford with Skirrid Fawr in the background, late 1930s.

12. Entrance to King Henry VIII Grammar School, Abergavenny.

13. Raymond Williams and Margaret Fallas on the boat, ‘Evian’, on Lake Geneva, 1937.

14. Harry Williams in his Sunday best, late 1930s.

15. Raymond in 1939 ready for Cambridge.

16. Joy Dalling, aged 13, Devon 1933.

17. Joy Dalling and her friend Annette Hughes, Cambridge 1940.

18. Joy Dalling, Cambridge winter 1940.

19. Joy Dalling, Cambridge summer of 1940.

20. On the roof above Michael Orrom’s rooms in the Turret of Trinity’s Great Court, summer 1941. Raymond is on the far left with Anne Richmond between him and Orrom who is flanked by two other friends.xvii

21. Enrolled in Royal Corps of Signals, Prestatyn, summer 1941. Back row, second from the left.

22. Wedding photograph, Salisbury, June 1942.

23. Raymond and Joy Williams in Barnstaple, 21 June 1942. Their wedding day.

24. Raymond in foreground with binoculars, winter manoeuvres Scarborough 1943.

25. Raymond in Holland, autumn 1944. On the back he had written: “These foolish things remind me of you”.

26. Anti-tank guns salute the silence of victory, north-west Germany, 1945.

27. Raymond, Joy and Merryn, on leave, 1945.

28. Llwyn Onn, the house in Pandy to which Harry and Gwen moved in 1948 from Llwyn Derw across the way.

29. Raymond in 1951, Chatto and Windus publicity shot.

30. Raymond with Joy and Merryn and Ederyn seated and Madawc between them, Seaford, 1951.

31. Raymond Williams at home, Hastings, 1953.

Front cover: Raymond Williams, Cambridge 1941.

Inside front cover: Raymond Williams, Geneva 1937.

Back cover: Raymond Williams, early 1960s.

xviii

Biographies always lie, because they impose a clear pattern of development, whereas, in fact, to any man who watches himself, development goes this way and that, back and forward, almost every day. The biography of an hour of a man’s life might have some point; it is always the sweeping line that betrays us.

Raymond Williams, The Grasshoppers (1955)

Introduction

Writing the kind of novel in which I was interested was a long process, full of errors, and the delay meant that I became first known as a writer in other fields.

Raymond Williams, 19661

He had not wanted it to be the way he would become known as a writer. From 1946 he had spent more time and expended more energy in writing fiction than anything else. When he retired in 1983 as Professor of Drama at Cambridge University, where he had taught English since 1961 and from where his reputation as an intellectual and academic had been rooted, he was quick to say that he had always considered himself as a writer first and foremost, not an elevated member of a Professoriate he typically disliked and mistrusted. The antipathy was no one-way street. His paradoxes were readily seen as self-willed contradictions.

Here was a man who lived most of his life in England and at the core of a literary establishment but sought to subvert the latter and by-pass the former by thinking of himself as a “Welsh European”. His work was inflected with Marxism and its myriad challenges, and though he consistently shied away from being pinned with the label of “Marxist”, he never denied its increasing definition of his own direction. He could see no human society of worth that did not cohere to the concept of community; at the same time he welcomed social change as the catalytic agency for a common culture. Undeniably, though, in his own life he lived in a manner which, despite a natural warmth and kindliness, shunned the close company of others, whether as friends, colleagues or students. It was as if the unrelenting pace he set himself in his work needed the self-contained dynamic of a long-distance runner and so the support he needed was that of constancy, not the acclamation for a short burst of success. He said it was a long revolution and he lived it as he meant it. 2

How he dreamed was another matter. That life of the mind took him ever back to the Black Mountains of his birth near Abergavenny, the crucible of his life and of his fiction. With a late exasperation in 1979, he would insist that in England the holistic effort of his work was not readily appreciated and that only in Wales did he have a sense that there was an appreciation of its unity.2 With a few lone exceptions it has remained true that the fiction – six published novels – has not overtaken his work in “other fields” even for his admirers. That does not alter the significance he gave it both early and late. The tension was there even as he prepared for the belated publication of the first great novel in which he found the form to articulate his case.

He had written to his publishers, Chatto and Windus, in early April 1959 in the wake of the phenomenal reception of his 1958 book Culture and Society, to tell them of his future writing plans and notably of that volume’s “natural successor”, The Long Revolution, which was to have “three parts – theoretical, historical, and critical – on the development of English culture”, and was “not literary criticism, or only very partly so” but rather “essays on the development of the reading public, the press, the educational system and standard speech forms [taking]… certain key ideas – class, mobility, exile –… in both literary and sociological terms, in what amounts to an attempt at a synoptic analysis of contemporary society”. With the appearance of The Long Revolution in 1961 his impact on contemporary British life, over the almost three decades that remained of his life’s span, was assured. Yet in the 1959 letter, this future is firmly prefaced by a past that was, for him, both adjunct and anticipatory:

To me the first and most important thing is that I have finished a novel that I have been working on for several years. I sent you some time ago a draft of part of this, but the finished work is quite different. It is now being typed, and perhaps the main thing I want to know from you is whether you really want me to submit it to you. In one way all my plans hinge around it, because, having considered the problem very carefully, I am certain that it is the next 3thing of mine I want to appear, to fit into the development of my writing as I see it… in a way my writing is held up until something is settled about this.3

The draft had been of Border Village, his re-working of 1957, in which the narrative moves chronologically forward from the arrival of the railway signalman, Harry Price, and his new bride, Ellen, to the village of Glynmawr where their son Matthew will be born. From here we follow their lives, through the 1926 General Strike and its fallout, to the son’s departure for university as the Second World War begins. This is the linear narrative that would largely hold steady. What was being typed in 1959, however, was the complication of the story that the death of Williams’ father in 1958 had impelled him to write: the return of Matthew, now a university lecturer in London, to the village and his father’s sick bed. This version had been called A Common Theme and it took the autobiographical traces even further away by building the story of Matthew, and his estranged wife Susan, into a parallel account that was spelled out in such detail that it threatened to overwhelm the primary relationships with its gloss. So it was not “finished work” even yet. In November 1959 he wrote again, this time to his long-term contact at Chatto, Ian Parsons, to say how delighted he was that both Norah Smallwood and Cecil Day Lewis at the firm liked what he now referred to as Border Country: “I shall be very willing to revise… It means too much to me to have any feeling of holding back from all necessary work on it… [and]… it would be preferable… to bring the novel out first”.4 The revisions removed lengthy passages of dialogue and the extended Matthew Price story.5 What was left was a family-at-a-distance of wife and children to which Matthew would return and, crucially, a new beginning to the novel, which would place Matthew amongst them, and sketch his intellectual quest as a professional historian. Only then do we plunge into the novel of generations, notably of Sons and Fathers, which Border Country had, at long last, become. The burden of that intricate novel, and of this present book, is that if Raymond Williams’ meaning for us 4is to deepen we will need to be clear about his resolute attempt to keep his work, all of it, both as part of a “whole way of life” and integral to it. It has always been more convenient to do the opposite. But, then, that was another manifestation of the division of “Culture” in society against which he mounted his life-long struggle. He knew the irony of himself being parcelled out and packaged up.

Those “other fields” of literary criticism, cultural theory, social commentary and media analysis – all bundled together as the influential corpus of Cultural Studies for whose origins he was, alternately, as a key figure cursed and blessed – were still the fields for which he was singled out in the heavyweight obituaries that followed on his early death in 1988. Yet as soon as his work had come, from the late 1950s, to receive wider notice he had insisted that his imaginative work, and his novels most notably, were all of a piece with his intellectual intentions. He had already clearly spelled it out in the mid-1960s when his status, middle aged guru of a Cambridge don to a whimsically self-absorbed generation, was already distorting his underlying meaning:

I am mainly interested in the realist tradition in the novel, and especially in the unique combination of that change in experience and in ideas which has been both my personal history and a general history of my generation. I have been glad to be able to write about this change in critical and historical ways, for the cultural tradition I encountered in Cambridge seems to me deeply inadequate and needing challenge in its own terms. At the same time, the whole point of these general arguments was a stress on a new kind of connection between social, personal and intellectual experience (which have all been diminished by being separated), and I am still excited by the challenge of learning to express this connection in novels, difficult as this continues to be. I see this as my main work in the future.6

When he died, unexpectedly and unpreventably, of a ruptured aortic aneurism from a valvular disease of the heart in January 1988 at his 5home in Saffron Walden, he was only sixty six and, true to his word, was deeply engaged in writing fiction. After his death, Joy Williams collated that episodic novel of time and place and published People of the Black Mountains in two volumes in 1989 and 1990. Although his former student and Cambridge colleague, Terry Eagleton, hailed it in The Observer as “Williams’ major literary achievement”, and others claimed it for innovation in the style and form of the historical novel, it divided critical opinion in the manner of all his fiction. Its detailed attention to what he understood as “realism”, a connection between the circumstances of people’s material lives and their awareness of both their own fate and their own possibilities, had been meticulously researched by Joy Williams.7 But it was all fed into the hopper of an imagination that was resolutely and deliberately not attuned to current literary fashion and the flotsam of 1980’s taste. Worse than that, here was a writer who was viewed – even by those sympathetic to the confrontational stance and somewhat detached personality he could affect – through the teleology of a distinguished Cambridge career even as Williams himself steadily denounced significant aspects of the place, its academic inhabitants, its intellectual pretension and its social snobbery. The Left could be as disenchanted with him as the Right. And it was in the novel form, again, that he chose to do the damage, immediately upon leaving the University in 1983, by writing Loyalties (1985), a fictional work impelled forward by the Miners’ Strike of 1984-85 but tenaciously grounded in the touchstones of experience that he dated episodically as “1936-37”, “1944-47”, “1955-56”, “1968” and “1984”. It was scathing in its denunciation of blind faith, misplaced loyalty and straightforward betrayal as exemplified by successive generations. It pivots around what for Williams remained the crucial and irreducible experience of class formation in British life.

He puts it most succinctly and angrily through Gwyn Lewis, the “natural son” of ex-Cambridge and ex-communist, Sir Norman Braose, who has been left by his father to be brought up in a working-class home in South Wales. Lewis is fully aware of the “general solidity of the argument” that must not allow a collapse from politics into mere 6parochial feeling, yet, in 1984, he is still uneasy about the easy assumptions:

… the Braoses were often quicker than his own people to talk the hard general language of class. Where Bert or Dic would say “our people” or “our community” the Braoses would say with a broader lucidity, “the organised working class”, even still “the proletariat” and “the masses” [and] – he had been told, kindly enough, that the shift to generality was necessary. What could otherwise happen was an arrest or a relapse to merely tribal feeling. And he had wanted even then to object: “But I am of my tribe.”8

It was not that Williams had not been saying this, in his own voice, elsewhere and in different forms. Indeed, that insistence, egotistical or self-obsessed some thought, was exactly what for such critics marred his finest critical works. From Culture and Society in 1958 to The Country and The City in 1973, he at times placed himself – squarely as an individual – within his dissection of the social distortion and cultural morass of modern Britain; all too much in your face if the cool disinterested scholar was the required model. It was certainly something that was inescapable about him. He felt the sting of ad hominem attacks in his own lifetime, and notably on the publication of The Long Revolution in 1961. After his death the personal opprobrium sometimes went far beyond his opinions to caricature his personality and even sneer at his upbringing. In 1990 R.W. Johnson in a wide-ranging review-article latched onto Williams’ Welshness as a catch-all explanation for what Johnson saw as unwarranted fame and bewildering respect for a “repetitive” and “empty” thinker. The metropolitan disdain – or is it the howl of the colonial confronted by a native disrespect for the former’s spiritual centre – is exquisitely, if unintentionally, a late Victorian pastiche in its dripping prejudice. Thus, the resolutely prosaic Williams is said to possess “a sort of lilting Welsh lamentation”; Williams, non-Welsh speaking and scarcely a chapel-goer, had “the style… of the Welsh nonconformist chapel… a quality of cadence and incantation”; to hear 7properly one of Williams’ written perorations “one should inwardly listen to it in its original Welsh accent”. That would be the one Williams did not have then since he spoke, as many others have commented, very deliberately and with the slight but distinctive burr of his native border country. Nor could Johnson resist (as he called for “a whole new intellectual beginning” for which the “greatest danger… will be to get trapped within the rhetoric of an exhausted tradition”) a passing double-handed swipe against the Welsh working-class Williams who, apparently, “as a young working-class scholarship boy up at Cambridge seems to have decided, like not a few Welshmen before and after him, that the way to storm this alien citadel, was to overwhelm it with a tide of wordy socialism”. A typically laconic Welsh reply, if it could be heard above the laughter, might be that this is more fictive than the fictional works Johnson ignores. But he was right, in principle if not in fact, about the biographical drivers to all of Williams’ work as this book will, in different mode, reveal.9

John Higgins, though in a dissimilar vein, also recognised that Williams’ life was “a central and defining characteristic of his work: its unusual biographical impetus, its powerful sense of an integrity and focus located in the personal voicing of the academic”10; whilst John McIlroy, noting the sympathetic welcome but relative lack of emphasis in Williams’ thought in the 1980s to “the new movements of women and black people and… the environment”, was sure that it all lay in “a continuing commitment to the working class, remarkable in its intensity… the values of his youth”.11 What follows will underline, in particular, the truth of both these insightful observations. Yet that is not to say there were no variations in the Williams persona or contradictions in his work. He would characterise them as explorations and accommodations within a framework of personality and principles that he had created, in struggle, between 1939 and 1958. The achieved self-assurance accommodated flexibility and change.

Williams returned to Cambridge, and as in 1939 by invitation without any formal application, to a Fellowship at Jesus College in 1961, just a year after he had re-located himself and his family to be a 8Staff Tutor for Oxford’s Extra-Mural Delegacy within Oxford itself, rather than in its outreach areas of Sussex where he had taught in Adult Education since 1946. So far as he was concerned, he was taking on an official English culture in its most important bastion; yet he had been appointed to a University Lectureship in the Facultyfor his contribution to that cultural tradition. By the time he arrived he had published The Long Revolution, a work that melded literary, cultural and sociological analysis as nothing else had done. It gave offence for its iconoclasm. Its best-seller status infuriated even more. By the middle of the 1970s his London publishers alone had sold over three quarter of a million copies of his books. The pattern continued. In his lifetime, his critical works were translated into Catalan, Danish, German, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and Japanese.

He wrote novels – Second Generation (1964) and The Fight for Manod (1979) – which dealt with Welsh society and Welsh working-class experience. They were unremittingly rooted in his past and on the way in which, on a wider generational front, he saw that developing. He wrote in a vein that he had secured finally for his own voice and never wavered from its unfashionable tone; and even when he wrote a political thriller – The Volunteers (1978) – it was with the preoccupations of his marginal country that he grappled. They were his own. He had joined and worked for the Labour Party between 1961 and 1966 but had left, in despair at Wilsonian tacking at home and abroad. He took out a Plaid Cymru party card for 1969 and, though he did not keep up membership beyond that year, he was, as he put it, a “Welsh European” by the mid-1970s with a belief that reformist politics and a rigid “Yookay” Unionist stance were inseparable.12

Early alliances between the late 1950s New Left and former Communist Party dissidents had promised a route back into formal political engagement for a very detached Williams, and he was soon a Board member of the magazine New Left Review. When the “old” New Left, principally represented by Edward Thompson and the “new” New Left, spearheaded by Perry Anderson, split and quarrelled acrimoniously and entertainingly by the mid-1960s, Raymond Williams remained 9valued, if not always liked, by both sides. By then he seemed to embody, perhaps because of his earlier and chosen isolation, a “Negative Capability” that could tease impetus from despondency. Edward Thompson, who had in 1965 left Adult Education to become Director of the Centre for the study of Social History at the new University of Warwick, wrote to him in February 1967 just after the first stirrings of the impulse to write a new Manifesto for the Left had begun:

Dear Raymond,

May I express to you my unreserved admiration for the way in which you have pulled us round and given us a new opportunity? You must have sensed you alone could have performed this role, uncongenial as it may be. I will confess that 3 or 4 years ago when the new left was collapsing at all sides, I deeply wished you to make an active intervention, and I felt a shade of resentment that this did not happen. Now I feel that I – and all of us – are wholly in your debt. I confess my political – not my ultimate – morale has been low (and Stuart’s also), and you found the language and the arguments I needed .……….We should be looking for men and women in their late twenties and thirties who must take the thing on and make it their own. Thank you: that was the first political meeting I have attended for 4 years and not come back from in a state of depression. Can I say fraternally?

Edward

It was subsequently in Williams’ rooms in Jesus College that Edward Thompson, Stuart Hall, Bob Rowthorn and others devised and wrote The May Day Manifesto in 1967, and it was Williams who is largely credited with holding it all together and then editing it for Penguin in 1968. If that was a shift leftwards from his only slightly earlier commitment to a Labour Party for whom Joy Williams had stood unsuccessfully for the Council in Cambridge, it was still a distance from the stern programmed Marxism of New Left Review. Even so it 10was Raymond Williams who was accorded their highest accolade as Britain’s most significant socialist intellectual when that extraordinary compendium – a new kind of book – of interviews, Politics and Letters, appeared in 1979, after his inquisition by Anderson, Barnett and Mulhern. The influential portrait that emerged through the mirror of selected questions and reflected answers is, to be sure, a likeness but it is one of its own moment of capture not of the unfolding and sometimes disguised life he had led.

At Cambridge he continued to write on drama and on the novel – Modern Tragedy (1966); The English Novel from Dickens to Lawrence (1971) – and to build his reputation with almost weekly reviews in The Guardian solicited by its dynamic Literary Editor, Bill Webb. He now eclipsed Leavis as the Cambridge name, and students vied to become his pupils or just to attend his packed, inevitably ruminative, lectures. If he failed to pay sufficient attention to their needs – as David Hare once resentfully alleged – or did not advance quickly enough towards the ideological bun party – Terry Eagleton later retracted his serpent’s tooth – he could be, and was, depicted as self-serving or even timid. Fame brought such demands without a concomitant understanding of how stretched he was or, more pointedly, of how much less he thought of those teaching obligations, undergraduate and graduate both, than he had of his adult educational ones. Yet, for every disgruntled encounter, there were, from those Joy referred to as “Raymond’s young men”, friendships, debts, obligations and acknowledgements that bore different testimony to his gifts of patience and interest. It was it seems – for Bob Woodings, Patrick Parrinder, Ian Wright, Stephen Heath and Lisa Jardine – how you chose to encounter him that brought the most lasting rewards.13 Certainly, many of those meetings with Raymond Williams, both with the man and his mind, during his life and after his death, seem freighted with the burden of expectation: especially over his total integrity as if he must be blameless in all things personal since he was so demanding of the behaviour of societies; over his lack of sociability to those who did not, perhaps, appreciate or admire the depth of his domesticity and the kind of partnership he had formed 11with Joy Williams. What holds true for the known life of Raymond Williams after 1961 is its assured position in the cultural history of twentieth-century Britain – “we have lost our best man”, Edward Thompson generously wrote of him on his death – and, as a socialist intellectual and writer, a figure of significance across the globe. From all that published work, we can measure him and mark his life as a public figure against it. What has not been seen is how the earlier making of Raymond Williams, unknown or misunderstood in detail, contributed to that full measure. The intention of this book is to show that his meaning – the very thing he meant by Culture as a “whole way of life” – lies in his own making through the struggles of his first forty years from 1921 to 1961.

I have tried to tell this story, where possible, so that the voice of Raymond Williams, in his own words, can be heard; to let the reader see the makings or the drafts that became published works and to read the work – fiction and otherwise – that has never before reached the printed page. It is all of a piece with the direction of an inner life which was, though definitely focused, never straightforward and so allows me to hope I can counter, by ranging backwards and forwards over the area of his life even as its line moved inexorably on, his own anti-biographical dictum from the manuscript of his 1955 novel The Grasshoppers: “Only the line of a life, hardly anything of its area, can be articulated, and reduced to grammar”.

I hope readers can now see for themselves the circumferences of his life and how he moved within and across its boundaries before he became the public figure from the late 1950s whose difficulty, in one sense, became what not to publish, since everything he said and wrote from then on was liable to find itself in print. His life story thereafter moves along the lines of familiarity that the obituarists and analysts could readily follow or choose to unravel after the event. There are few unexpected biographical revelations from the 1960s, beyond the work itself. He had begun the plotting of another novel, The Brothers, on which, as was his custom, he worked intermittently, alongside other projects, from the early 1980s. That would have been another tale of 12exile and return, and of rediscovery of the past and a possible future, set inevitably on the Welsh Border Country which was always the territory of his imagination.

For this present book, however, it is possible to range further and deeper into the area beyond the border lines because of the astonishing volume and richness of the papers I have been allowed, unreservedly, to use. Not only do they give us, in my view, a new Raymond Williams, a “Jim” you might say, but they also incisively confirm the core values of the one who addressed many issues, from the 1960s, with his sense of himself and his beliefs stubbornly present.

The tantalising and occasionally misleading references to early work as mentioned in the interviews he gave in Politics and Letters (1979) are, in this book, present in the actual detail of early stories, essays and plays from the Pandy schoolboy to the Cambridge undergraduate. Here, too, are the guideline diaries of Harry Williams, the father whose story parallels and, in the end, profoundly shapes that of the son. There are also his war-time letters to his wife, a war diary and occasional letters to and from early acquaintances – though he was not a regular correspondent beyond brief notes, either during the War or later.

I have interviewed many who knew him, young and old, and thanked them in the Preface. Extensive taped and untaped conversations with Joy Williams took me down many unexpected directions and to other documented sources. I travelled after Williams from Pandy to Cambridge, across the battlefields of Normandy to Brussels and on to the suburbs of Hamburg. I came to understand the war period as the most crucial, and still puzzling, piece in his mental make-up. A trickle of papers, some in manuscript, some typed, became a dauntingly incessant flow after 1945: successive drafts of novels, fragmentary and near complete, enough short stories for two volumes, film scripts, documentary and dream-like, radio talks, submitted and unpublished novels, work drafts for adult education classes and essays, the first scribbled stirrings of thought for his cultural and historical papers, hares set running and half pursued for new drama or fictional concepts, and above all from the mid-1950s, squat notebooks in which 13Culture and Society and Border Country, his twinned lodestars, are conceived and born.

The book has grown to accommodate all this and more because I also came to understand that we cannot grasp the Raymond Williams whose work has so reverberated across the world, to the frustration of many he once annoyed and would still be delighted to annoy, until we saw close-up the immense creative and psychological effort of his first forty years. This is a biographical study whose impulse is to reject any overt disjunction between the life and the mind, not least because it was a separating out Raymond Williams resented, as description, for himself and others.

Using the papers that lie behind both the period of relative obscurity and his subsequent success I have tried to reveal the importance, as I see it, of his personal and intellectual conflicts in the context of twentieth-century British history. He was against much of the grain of it when alive and always for the reason that he saw, having experienced it directly, that individual empowerment, material betterment or even the acquisition of knowledge, is another form of disempowerment if there is no common culture, no collective gain, no full recognition of the social implications of human equality. For him, both in his own time and as he later affirmed, “in different places and in different ways”, the social formation of class, the negative divisiveness as well as the positives of communities made and renewed, lay at the centre of this civilisation and our ongoing discontents. The novel was his way of appropriating these general arguments in order to make them, as they were experienced, individual dilemmas and individual solutions within the given framework of a binding social and material history.14

We might almost say that his work, all of it, was written only because he had lived it, and that though it may indeed be studied without knowing his life, it cannot be fully comprehended without the texture of that life being known. It was what, conceptually, he felt he was distilling as the knowledge of experience into recoverable form in his novels, most notably in Border Country, where the main and fictive story is, finally, that of the signalman Harry Price and his growth, 14through crisis and settlement, to his end. Matthew, the son, ends the novel on its last page by telling his wife, Susan:

“I remember when I first left…, and watched the valley from the train. In a way I’ve only just finished that journey.”

“It was bound to be a difficult journey.”

“Yes, certainly, only now it seems like the end of exile. Not going back, but the feeling of exile ending. For the distance is measured, and that is what matters. By measuring the distance we come home.”

Border Country is not autobiographical except through its place and its time. Its own measured end is Williams’ final and intended summation of its meaning. But for his life, and so for the biographer, the clues from what is discarded can, and should, speak more insistently of the rawness of a life as it was being lived and experienced.

A few pages before the end of the published version of Border Country Matthew tells Susan that he had always thought his father “was good, my whole sense of value has been that. And since I’ve left home I’ve watched other people living, and I’ve become more certain”; and she replies, “You don’t have to prove it… If you believe it, you’ll live by it”. But what was crossed out and excised between that and the final published version is the following passage, something maybe too explicit for the novel, certainly for his publishers, yet a statement from Matthew which clarified the personal endeavour Raymond Williams had, by 1958, made abstract in his critical work:

“… and I’ve become more certain. I even see the thing socially: that his class is good; that it is better, in human terms, than the class I’m invited into. And then again, they wait in the margin, with the obvious comment. That I am idealising his class, and that I do this to hide my aggression: that basically I hate him, and despise the people I came from.”15

“Yes, they’re very smart,” Susan said smiling. “And of course they resist the idea that the people they despise are as good as themselves.”

“I said better,” Matthew insisted.

“That would be utterly ludicrous,” Susan laughed.

“Yes, but I’m saying it. Not in personal virtue, but in the ways they live.”

“You don’t have to prove it,” Susan said. “If you believe it you’ll live by it.”

“And the idealising it?”

“If it is that even, you can make it real.”

“You think it is that, then?”

“No, I’ve never thought so.”

“It all fits, you know,” Matthew said.

“Any system fits, that is what it is for. And what this is for, in the end, is to dismiss other people. It’s a way of seeing people, that has become established, so that almost every human effort is, in the end, degraded.”

“This is to find out the lies,” Matthew said.

“You can’t live a lie, in the end. What you do will be the truth.”

“Well, what am I doing?”

“What you wanted to do. What he wanted you to do.”

“Both?”

“Yes, both.”

“Except that I’ve done very little. Anybody can plan things.”

“You complicated what you’d started with.”

“Exactly. Perhaps as a way of preventing it.”

“Does it feel like it? Yes, the thing could have been finished, but is it a loss to be driven back down?”

“In this society it is. One is valued on production.”

“But that is the whole crisis. That’s what you’ve been watching, in him.”

“I’ve been watching death.”

“Yes, that is part of it.”15

Notes

1 Typescript prepared for Midcentury Authors (New York) 1966 in Raymond Williams Papers, thereafter as RW Papers.

2 See Raymond Williams, Politics and Letters: Interviews with New Left Review (London: Verso, 1979), pp. 295-6 where, contemplating his “more conscious Welshness”, he added that “Welsh intellectuals offer recognition of the whole range of my work, which literally none of my official English colleagues has seen a chance of making sense of”.

3 Letter from Raymond Williams to Norah Smallwood, 5 Apil 1959. Chatto and Windus Files, University of Reading.

4 Raymond Williams to Ian Parsons, 2 November 1959. Chatto Files.

5 See suggested cuts in letter from Ian Parsons to Raymond Williams 7 December 1959. Chatto Files.

6Midcentury Authors, op. cit. 1966.

7 See various Files of historical notes compiled by Joy Williams in RW Papers. Joy Williams (1918-91) kept the cottage in Craswall in the Black Mountains which they had bought in the early 1970s, but it was too remote for her to live in and she bought, after his death, a house in Abergavenny where she briefly lived before her death from an untreatable brain tumour in a Cardiff hospital in 1991.

8 Raymond Williams, Loyalties (London: Chatto and Windus, 1985), p. 293.

9 See R.W. Johnson ‘Moooovement’ in London Review of Books, 8 February 1990. Johnson, a South African political scientist then based in Oxford, never let this bone go; though in the case of Neil Kinnock who was unremittingly thought to possess neither the education nor the intellect to become Prime Minister, Johnson was at least pitch perfect about that politician’s accent. And nothing else.

10 John Higgins, Raymond Williams: Literature, Marxism and Cultural Materialism (London: Routledge, 1999), p.9.

11 John McIlroy and Sallie Westwood (Eds.), Border Country: Raymond Williams in Adult Education, (Leicester: NIACE, 1993), p. 17.

12 Plaid Cymru Membership Card, 1969. RW Papers. And see Raymond Williams interview with Phil Cooke, 1984, where he says, in rather flexible mode: “In the 1960s and 1970s I felt close to the arguments being put forward by nationalists leading up and during the devolution debate [i.e. to 1979]. I even joined the Welsh party [sic] for a year or two; however, I 479found it difficult to discharge my obligations living at a distance from Wales. I felt my thinking on culture and community was more reflected there than in the nationalism in Wales, especially its traditional difficulty with adhering to fully socialist principles of common ownership… I was told at the time by those inside and outside that I was idealising it, but many of its ideas remain closer to me than those of the contemporary Labour Party. I think there was just a coming together – a tendency and a movement on the ground developing against centralism”. Re-printed in Daniel Williams [Ed.], Who Speaks for Wales? Nation, Culture, Identity: Raymond Williams (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2003), p. 206.

13 Interviews by Dai Smith with Joy Williams and with Stephen Heath, Patrick Parrinder, Bob Woodings, Terry Eagleton, Ian Wright and David Holbrook in October/November 1990.

14 Michael Rustin argues in ‘The Long Revolution revisited’ that the continued relevance of Williams’ ideas lies in his “imaginative mode of understanding” which takes us beyond the notion of the working class as the incubator of social advance to the sense of the values that were attached to its aspirations being common to the potential of all citizens: “We can most valuably take from Raymond Williams the idea of a “whole way of life” as potentially subject to continuous learning and remaking over time. His conception of socialism as universal human creativity and agency based in cooperative and democratic social relationships, transcends its historical origin in the experience of industrial labour”. Soundings: A journal of politics and culture. Issue 35 April 2007. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

15 Unpublished Ms. pages of Border Country. RW Papers.

Chapter 1

A Settlement

Eighteen-year-old Harry Williams, dressed in the navy blue serge porter’s uniform and cap of the Great Western Railway, carried the lady’s cases across the platform as he had habitually done since joining the Company in the early summer of 1913. He had left school aged twelve to work as a boy labourer on first one and then another of the big estates near Hereford. He kept his first employers’ hand-written testimonials all his life. George Roper of Tyberton had employed him for two years (from 1910) and had “always found him a respectable, honest, quick boy and his personal character very good”, whilst J. Farr of Arkstone Court, Hereford wrote: “to certify that Harry J. Williams has lived with me since Sept 30th last [1912] and I have always found him honest, sober and obliging.”1