13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

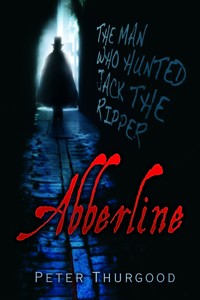

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The name Frederick George Abberline has become synonymous with that of Jack the Ripper, and he has been portrayed as everything from an alcoholic, a drug addict, a womaniser and a bully. In reality Abberline was none of these but instead was a devoted husband and a dedicated policeman in a time of rampant corruption. Furthermore, the Whitechapel murders were not the only notorious cases he worked on. From his humble origins as a clockmaker through to his rising through the ranks of the Metropolitan Police, Abberline tells the story of a man who lead some of the most infamous investigations in criminal history. Long before the Ripper, Abberline infiltrated an Irish terrorist group known as the Fenians, before he became embroiled in the Cleveland Street Scandal – an incident that almost brought the Government to its knees. When he retired from the police at the age of 49, Abberline had received eighty-four commendations and awards – a testament to his tenacity and ability.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Foreword

1 The Cleveland Street Scandal

2 Early life – Undercover Work and Marriage

3 The Whitechapel Murders

4 In Charge?

5 Leather Apron

6 Searching for the Real Annie Chapman

7 Arrests

8 When Evidence is not to be had – Theories Abound

9 The Double Event

10 The Final Ripper Victim

11 Hell

12 The Suspects

13 Abberline’s Number One Suspect

14 The Argument For and Against Klosowski

15 Highly Implausible?

16 Another Ripper Suspect?

17 Did Abberline Know the Identity of the Ripper?

18 Victims

19 An Inspector Calls

20 Retirement Beckons

Plate Section

Copyright

Foreword

The name Frederick George Abberline, later to become Detective Inspector Abberline, has become synonymous with the Whitechapel murders, particularly those attributed to ‘Jack the Ripper’.

Indeed, the murders have been shrouded by controversy from day one. We have been led to believe that Jack’s reign of terror spread like wildfire through the streets of London; that the population were too scared to leave their houses at night. The Star newspaper wrote an editorial in September 1888, stating the following:

London lies today under the spell of a great terror. A nameless reprobate – half beast, half man – is at large. The ghoul-like creature who stalks through the streets of London, staking [sic] down his victim like a Pawnee Indian, is simply drunk with blood and he will have more.

At the time of The Star’s editorial being published, the second murder attributed to the Ripper had only just taken place, and considering that murders were not exactly scarce in London at this time, these two did not score as being very significant to London’s crime figures, apart from the fact of their ferociousness. We need to bear in mind here that this ‘ghoul-like creature’ who was said to be ‘stalking the streets of London’ and casting his spell of terror upon ordinary Londoners had, in fact, only been in existence for just over one week.

The press at this time intimated that women were not safe in the streets, that people were hiding in their homes, too afraid to venture out after dark, and that bodies were being found scattered throughout the streets of London. The truth, however, was much simpler; two women had been murdered in the Whitechapel area of London, thus causing some panic, if any, in that area alone, and certainly not causing people to lock themselves in their homes.

From 31 August 1888, when the first victim, Mary Ann ‘Polly’ Nichols, was discovered, to 9 November that same year, when the body of Marie Jeanette Kelly was found in her room, a total of just five Ripper murders had taken place, over a period of ten weeks. All five Ripper victims were mutilated and dispatched with a grizzly precision, their throats slit and their entrails removed and displayed, almost in a sacrificial manner by someone with what has since been described as a considerable amount of anatomical knowledge.

If we are to believe this more reasoned version of the series of events that became known as the Jack the Ripper murders, then we must also discount the sensationalist reports of the press at the time, who much like their counterparts of today, would do almost anything to sell their newspapers. Their reports of a crazed madman terrorising a whole city and haphazardly butchering women on the streets is pure sensationalism carried out by journalists in order to make money.

Within hours of the first murder, letters started pouring into the press offices, and by the time of the last murder, more than 250 of them had arrived in the in-trays of the popular press, and all purporting to have come from the killer. It was in a letter received by the Central News Agency on 27 September 1888 that the name Jack the Ripper was first used. This letter was originally believed to be just another hoax, but three days later, the double murders of Stride and Eddowes made the police reconsider, especially once they learned a portion of Eddowes’ earlobe was found cut off from the body, eerily reminiscent of a promise made within the letter. The police deemed the ‘Dear Boss’ letter important enough to reproduce in newspapers and post-bills of the time, hoping someone would recognise the handwriting.

The image that was being popularised by the press was one of a blood-thirsty killer stalking women at random through the dimly lit streets of the East End, before ripping them to pieces for no apparent reason other than to satisfy his blood lust. From the letters that arrived on the editors’ desks, however, it is clear that although a few of them must have come from isolated cranks intent on generating a lurid terror in those that read them, many more were written by genuinely concerned members of the public. The character of Jack the Ripper nevertheless remains a paradox. His letters purport to come from a rough-and-ready ‘working-class man’ who had learned his writing skills in a ‘national school’, but their contents are cleverly headline-seeking, and the astuteness with which they were targeted, suggest that the senders came from a different stratum of society. As George R. Sims, the successful author and playwright, wrote in The Sunday Referee newspaper, in October 1888:

How many among you, my dear readers, would have hit upon the idea of ‘The Central News’ as a receptacle for your confidence? You might have sent your joke to the Telegraph, The Times, any morning or evening paper, but I will lay long odds that it would never have occurred to you to communicate with a Press agency. Curious, is it not, that this maniac makes his communication to an agency which serves the entire press?

Sims was by no means alone in suspecting that the authors of many of the letters, certainly of those purporting to come from the Ripper himself, were in all probability educated and worldly men who were fostering a reign of terror to underline their own political agenda.

From the first body found, there were rumours that the highest in the land were involved in the killings. As The Star wrote in November 1888:

We have heard the wildest stories … it is believed by people who pass among their neighbours as sensible folk that the Government do not want the murderer to be convicted, that they are interested in concealing his identity.

Could this be true? Inspector Abberline certainly didn’t think so. He was appointed to the case on 1 September 1888, which was the day after Polly Nichols’ disembowelled body had been found on 31 August 1888 lying on the ground in front of a gated stable entrance in Buck’s Row, Whitechapel.

Abberline worked on the Ripper case during its entirety, though unfortunately never procuring a conviction. It is this case that people know him for, but during the course of his career he did head up other investigations that resulted in much better outcomes than the Ripper case did.

1

The Cleveland Street Scandal

July 1889 was one of the hottest Julys on record. Office staff at the City of London Police headquarters at 26 Old Jewry had been given special dispensation, allowing them to work in their shirt sleeves; probably a first for this period in time, but not something carried forward to uniformed police officers. Even though Sir James Fraser was the Commissioner of the City of London Police, he did not receive any different treatment on this particular ruling than his uniformed officers. Sir James wasn’t an easy man to get on with at the best of times: an ex-military man who was used to issuing commands and having them obeyed without question, something that didn’t quite work in the same way in the city police force. He was also used to having his every comfort taken care of by his own personal batman; again, something sorely missing in his new post.

It came then as no surprise to his subordinates when he went absolutely berserk, after opening a letter addressed personally to him from Scotland Yard telling him to deal with a case regarding a series of alleged thefts from the London Central Telegraph Office, in St Martin’s le Grand. ‘Who the hell do these people think they are dealing with?’ he bellowed. ‘This is nothing more than a case of petty theft, I am the Commissioner, God damn it.’ He threw the letter across the room to the sergeant who had just delivered it, and told him to deal with it. The sergeant had seen Sir James in one of his moods before on several occasions, and knew instinctively when not to say anything; he just scooped the letter up, mumbled a brief ‘yes sir’ and left the room.

Police Constable Luke Hanks was on desk duty when the sergeant approached him and gave him his orders to go to the London Central Telegraph Office, where he was to be in charge of this investigation. The amounts of money, the sergeant told him, were believed to be mainly small sums, but added together they could become a considerable amount. ‘If you handle this correctly,’ the sergeant said, ‘it could lead to promotion, so get over there and be thorough in your investigation.’

PC Hanks couldn’t wait to get out of the heat of the office, and the thought of being in charge of his own case, with possible promotion at the end of it, prompted him to move quicker than he had done for years.

One hour later, Hanks, with his note pad and pencil at the ready, was at the London Central Telegraph Office being shown into a room, which had been allocated to him to work and take statements. The room was not much bigger than a broom cupboard, with a tiny desk, two upright wooden chairs and one small window, set so high on the wall behind him that he could not see out of it, let alone reach it in order to open it. Hanks nevertheless entered into his work with gusto, and by midday he had interviewed and taken statements from at least twenty workers. Not only did Hanks carry out his work with verve and vigour, but he also stuck strictly to the rules regarding police dress code, meaning that he kept his heavy serge tunic buttoned to the neck and his large and cumbersome helmet on his head the whole time he was conducting the interviews. By the afternoon, however, the heat generated by the close proximity of the interviewees and PC Hanks, in such a small room, became more than he could bear. He was not, after all, a very young man: fast approaching 50, and with a little more body weight to carry around than he was prepared to admit.

No one from his station was likely to turn up, so at 4 p.m., Hanks decided to take a chance and take off both his tunic and helmet, along with a few pounds in weight which he had possibly shed as well. The heat, however, was still unbearable, even though he was working in his shirtsleeves, so while waiting for the next interviewee, he climbed up on to the desktop and wrestled with the catch on the small window, finally managing to ease it open slightly. The first draft of air that drifted through the open space was wonderful, cooling him down almost immediately, but along with the air, came something else: a smell so foul it almost caused him to vomit; for what he hadn’t known was that immediately outside this room was the stabling yard for the Telegraph Office’s horses. No wonder the window had been set high into the wall and kept closed. Needless to say, Hanks closed the window immediately, and preferred to sweat it out rather than try to open it again.

Weather-wise, the second day wasn’t very different from the first, and as there was no way he was going to have the window open again, Hanks decided to try to speed things up a little. Instead of just taking formal statements, which was very slow and laborious, he insisted on each staff member supplying a written statement, which would include all their personal details, as well as all monetary transactions they had dealt with in the last two weeks. Each interviewee then had to empty their pockets out on to the desk, where Hanks would make a note of the exact amount each person had on them. Younger members of staff, who were employed as telegraph boys, were strictly forbidden to carry any personal money on them in the course of their duties, purely to prevent any confusion as to whether such money could be classed as their own or the customer’s. This, of course, helped Hanks out a lot, especially when he called the next boy, Charles Thomas Swinscow, into the room, and asked him to empty his pockets on to the desk. Hanks was more than surprised to see the princely sum of 14s, which was approximately four weeks’ wages at that time, or around £400 today.

A look of satisfaction spread over Hanks’ face, as he stood up and started putting his tunic and helmet back on, which had been hanging on a hook behind the door. He felt that, at long last, he was getting somewhere with his investigation, and there was no better way to impress the young, and the gullible, than to confront them with authority; the overall look of his complete uniform would, he was sure, do exactly that.

‘How would you feel about spending the next ten years of your life locked up in a prison cell?’ he asked the young lad. Within minutes, the boy had broken down and was pleading with PC Hanks not to imprison him. He hadn’t stolen this money at all, he had earned it, he said. Hanks, however, begged to differ, pointing out that he would have had to work for a whole month to get such a large amount as this. He gave the lad an ultimatum: either say where the money had really come from or he would place him under arrest and charge him with theft.

Charles Swinscow was still in his early teens, and was almost at breaking point. The very thought of imprisonment would probably kill his mother, he said, let alone what it would do to him. He begged PC Hanks for mercy, saying he would tell him all he knew, if he promised not to gaol him. Hanks told the boy to calm down; if he started talking, he would do everything he could to help him.

Swinscow blurted out how he came by the money: he hadn’t stolen it, but had earned it from a man named Charles Hammond, for supplying services at his premises at 19 Cleveland Street, in neighbouring Fitzrovia. ‘Services,’ said Hanks, ‘is a very vague word, would you care to elaborate?’ The young Swinscow squirmed in his chair, his face starting to redden, and his voice lowered a tone as he explained that the ‘services’ he had provided were in the form of male prostitution for clients that Charles Hammond provided at his premises. He went on to say that he was introduced to Hammond by 18-year-old Henry Newlove, who worked as a General Post Office clerk. In addition to this, he named two 17-year-old telegraph boys, George Alma Wright and Charles Ernest Thickbroom, who also rented out their services to Hammond.

PC Hanks quickly realised that he was on to something much bigger here than petty theft from the Central Telegraph Office; for at this period in time, all homosexual acts between men, as well as procurement or attempted procurement of such acts, were strictly against the law, and punishable by varying terms of imprisonment. With this in mind, Hanks obtained corroborating statements from both Wright and Thickbroom. Once armed with these, it was much easier to squeeze a confession out of Newlove, which included him dropping several well-known names into the equation, probably in the hope of being seen as someone who was willing to help the police in every way he could. Amongst those named were Lord Arthur Somerset, who was the head of the Prince of Wales’ stables; Henry FitzRoy, Earl of Euston; and an army colonel by the name of Jervois. Newlove agreed that all these men were regular visitors to the Cleveland Street address, but said it was more than his life was worth to state this in writing.

PC Hanks began to realise that what he had stumbled upon here was probably a matter of great, maybe even national, importance, for these men were connected to royalty. When his superiors saw his report they would undoubtedly recognise the excellent manner in which he had handled the case so far, and hand him the much-wanted promotion that he so desired. This was what PC Hanks hoped for, and indeed expected when he presented his findings, along with the statements and confessions that he had obtained from the boys. But instead of the recognition that he craved for, all he received was an obligatory nod and a smile, coupled with ‘Well done Constable Hanks’. His superiors deemed the case far too important for them to handle on their own, and immediately passed it over to Scotland Yard, thus ending PC Hanks’ dream of obtaining promotion and the possible fame and money that went with it. He was immediately detailed to forget about the Cleveland Street scandal, as it became known, and to continue his work, in the miserable little office backing on to the stables, regarding the alleged thefts at the Central Telegraph Office.

Sir James Monro, was greatly worried by the names listed in Hanks’ original report, which were allegedly connected to the Cleveland Street case. There was no doubt in his mind that the case needed thorough investigation, but at the same time, he also felt that it needed to be handled in a very restrained manner. He feared if the press discovered such people as Lord Somerset, with his royal connections, might be involved, as well as the other names and their political implications, it could bring down not just the government, but possibly the royal family as well.

Monro knew that he had to tread very carefully indeed with this case; he needed a top officer in charge, but not one who would bring too much publicity along with him. The obvious first choice was Melville Macnaghten, whom he had great faith in, and whom he had earlier offered the post of first chief constable in the Metropolitan Police. This appointment, however, never came to fruition, as it was opposed by Charles Warren, who at this time, was London’s Commissioner of Police. It seemed that Warren and Monro had never had a great affinity to each other, which only succeeded in Warren’s rejection of Macnaghten, or probably anyone who Monro suggested.

With this ongoing rift between Monro and Warren, Monro decided to go for what some say he saw as a soft option: a name that everyone would recognise, but without any of the controversies attached that a more senior officer such as Macnaghten would possibly bring to the case with him. He announced, without delay, the appointment of Inspector First Class Frederick George Abberline to the case. Abberline had previously worked at Scotland Yard for almost a year, until September 1888, when he, along with several other officers, were drafted into H Division, Whitechapel, East London, working on the infamous Jack the Ripper case. Abberline’s move to East London came just after the disembowelled body of Mary Ann Nichols was discovered lying in the gutter of Buck’s Row, Whitechapel. Nichols was allegedly the first Jack the Ripper victim. I use the word ‘allegedly’ as there were eleven separate murders dating from 3 April 1888 to 13 February 1891, all of which were included in the London Metropolitan Police Service investigation. They were known collectively in the police files as the ‘Whitechapel murders’.

Only five of these murders, however, are counted today as definitive Jack the Ripper murders. The other six were kept separate, thus making a clear distinction between those of Jack the Ripper and those committed by a person or persons unknown. The murders were considered far too complex for the local Whitechapel H Division CID, headed by Detective Inspector Edmund Reid, to handle alone; which is why Scotland Yard were drafted in, and the name of Inspector Frederick Abberline became forever synonymous with that of Jack the Ripper.

Frederick George Abberline was 46 years old at this time, and had been in the police force for twenty-six years. Described as medium height and build, with dark brown, thinning hair and a friendly disposition, he sometimes walked with a slight limp, especially during the summer months, due to a varicose vein on his left leg.

Inspector Abberline wasted no time in organising the team appointed to him by Sir James Monro. He was determined to bring this case to a speedy conclusion. Armed with all the evidence acquired by PC Hanks, he quickly obtained two arrest warrants, the first being for the arrest of Charles Hammond, the owner of the brothel on Cleveland Street, and the second being for the arrest of 18-year-old Henry Newlove, who acted as a procurer for Hammond. The crimes they were to be charged with were for the violation of Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885. The law made all homosexual acts between men, as well as procurement or attempted procurement of such acts, punishable by up to two years, imprisonment with or without hard labour.

Abberline and two of his officers arrived at 19 Cleveland Street, at precisely 6 a.m. the following day, a time when most people were still in bed and an easy arrest almost a certainty. Abberline grasped the huge iron door knocker and banged it repeatedly as loudly as he could against the door. The two officers beside him stood with their truncheons drawn, ready to charge into the house the moment the door was opened, but unfortunately it never was; the occupants had long since flown the coop.

Had someone tipped the occupants off? With so many high-profile names involved, this theory certainly couldn’t be ruled out. Abberline’s priority at this time was to get into the house and carry out a thorough search to see if any clues had been left. In order to do this, however, he either needed someone to actually let him in or, failing that, he needed a search warrant, which would probably take another twenty-four hours to obtain. Applying for a search warrant would not only delay his investigation, it might also warn his opponents, if they didn’t already know, as to exactly what he was up to. He made his decision, and rightly or wrongly, told his officers to put their shoulders to the door and smash it down if necessary.

A few minutes later, Abberline and his men were inside the house, which looked very much as if the previous occupants had left in quite a hurry, with books scattered the floor, small pieces of furniture overturned, and vases and crockery smashed and broken. The larger pieces of furniture, such as beds, bookcases and armchairs, had been left, but little else. The lounge, which was elaborately decorated with red velvet flock wallpaper, a crystal chandelier and two plush day beds, was also bereft of any personal effects. After about an hour searching from room to room and not finding anything that might possibly give him a lead, Inspector Abberline decided to leave the premises. He paused for a moment by the street door, where he noticed a side table with a vase standing on it. The vase had a Chinese pattern and square base, and was exactly the same as one his parents had when he was a boy. Underneath the base, however, was something else. He discovered it to be a small black book, and a quick glance through showed it to contain addresses, which might prove valuable to his investigation. He didn’t have time to look at it in detail, so he stuffed it into his pocket and left.

Abberline knew that if he was to succeed in this case, he needed to make an arrest very quickly, as someone seemed to be one step ahead of him and relaying his moves before he made them. Leaving one officer to secure and guard the premises, Abberline hailed a hansom cab and hurried off with the second officer to Camden Town. He knew from the witnesses’ statements that Newlove’s mother lived here, and Henry Newlove sometimes stayed there when he was not with Hammond at the Cleveland Street house.

The driver stopped his cab at the end of a narrow alley, explaining that this was the address but it was too narrow for him to drive down. Camden Town at this time was known for its slums, and this alley, which didn’t even have a name exhibited anywhere, was certainly no exception. The tiny, two-up, two-down houses, many of which had broken windows and doors that looked like they were hanging off their hinges, didn’t look fit to house animals, let alone human beings. Abberline recognised Mrs Newlove’s house by the number 9, which had been drawn in chalk upon the brickwork beside the door.

From another house, somewhere along the street, he could hear the sound of a baby crying, but there wasn’t any sound coming from Newlove’s house. One of the officers peered in through the small window beside the door, and told Abberline that it looked like someone was still asleep in a bed. By now it was 8.45 a.m., a time when most people would be out at work. However, in this particular area of London, work wasn’t a word that rolled easily off the average citizen’s tongue.

A few loud knocks at the door usually did the trick, and got even the deepest of sleepers out of bed. As there was no knocker on this door, Abberline did his best to wake the house by pounding and kicking at it, only to find that it swung open of its own volition, having no lock as well as no knocker.

Abberline pushed the door open and called into the house, asking if anyone was there. A door to his right opened and Mrs Newlove appeared, holding a piece of grubby-looking material around her, probably one of the bed sheets. ‘Who are you?’ she screamed. ‘What do you want here?’ Abberline told her he was a police officer and he wanted to question her son. Mrs Newlove quickly moved in front of him, barring his way to the stairs, as she told him her son wasn’t there. Not exactly the best way of convincing a detective not to look on the upper floor. Abberline shook his head in disbelief as he told one officer to stay by the door and the other to follow him up the stairs, pushing Mrs Newlove aside as they did so.

There were two doors at the top of the stairs, both leading to tiny rooms with beds in each of them. The first room looked like it was also used as some sort of storeroom, piled high with what looked like second-hand clothes or rags. The second room contained just a bed and a wardrobe. The bed was unmade, but still warm to the touch, meaning they had found the right room and Henry Newlove had only just vacated it. A quick glance around also showed the most likely place for young Newlove to be hiding. Abberline nodded to his officer, who quickly drew his truncheon, as Abberline flung the wardrobe door open to reveal a very frightened youth, standing naked and trying to hide his dignity behind an old overcoat, the only item of clothing in there. Abberline pulled the bedclothes off the bed to see Newlove’s trousers and shirt that he had tried to hide. Throwing the clothes at Newlove, he told him to get dressed, and that he was under arrest.

Newlove was taken back to Scotland Yard, where he was formally charged and further questioned. During his questioning, he admitted that that he had warned Hammond, who had immediately locked up the Cleveland Street house and fled the scene to somewhere on the continent. This, he said, was after the initial police investigation into the missing money at the Central Telegraph Office, and the subsequent details of the Cleveland Street affair coming out.

When asked why he had warned Hammond, Newlove replied that his father had left him and his mother when he was just a child, and that Hammond had been like a father to him. Abberline didn’t answer Newlove on this, as he did feel sorry for anyone brought up in such circumstances, but as he later discussed with a work colleague, ‘Fathers don’t sleep with their sons, or sell their bodies to other men either’.

Whatever Abberline’s real feelings, he was still furious that his main witness had managed to escape so easily in this manner. If he could lose Hammond like this, it was possible other participants in this case could also escape the net, and he would be made to look a complete fool. As much as he didn’t like threatening witnesses, especially young and vulnerable lads of Newlove’s age, he didn’t see that he had any alternative. He threatened the young Newlove with practically everything he could think of, from life in prison to whipping, and even hanging, if he did not start co-operating and naming names. Unorthodox it may have been, but within hours, Newlove had made a fresh statement with a list of names that filled up nearly four pages. Most of the names were of unknown members of the public, but amongst them were some that stood out like proverbial sore thumbs, including Lord Arthur Somerset and the Earl of Euston, who were without a doubt no ordinary members of the public. Lord Somerset was the third son of the Eighth Duke of Beaufort, a much-decorated major in the Royal Horse Guards, and equerry to the Prince of Wales and superintendent of his stables. The Earl of Euston was the eldest son of the Seventh Duke of Grafton and a prominent Freemason.

The naming of Somerset and the Earl of Euston by Newlove was exactly what Abberline needed; there could be no case worth proceeding without such names. Even though the Cleveland Street house was now closed, he was sure that there would be some customers who were unaware of this. His next step was to post surveillance teams of undercover officers to watch the Cleveland Street address, and take notes and descriptions of everyone who tried to gain access there. During the next few weeks, Abberline’s team noted the comings and goings of a great number of potential customers to the address, as well as their descriptions, times of arrival and departure etc. They also noted, with some glee, many of the visitors’ visible disappointment when they found the premises closed.

Inspector Abberline was still smarting from the fact that he had not managed to solve the Jack the Ripper murders just a few months earlier. It was probably this fact, more than anything else, that drove him relentlessly to do his best to bring swift justice to the Cleveland Street case.

Detectives in those days, just as today, worked very closely with their informants, and within days a reliable source came up with some very important information regarding Hammond’s whereabouts. Hammond was now living quite openly in Paris.

Armed with yet another arrest warrant, a very determined Inspector Abberline boarded the next steamer to France and made his way to Paris, where he contacted the French Sûreté, in the hope of securing their co-operation in extraditing Hammond. The one thing that Abberline had overlooked, however, was that he knew absolutely no French at all. Like most people at that time, and probably more now, he expected them to speak English. Whether the officials he met in Paris could or could not speak his chosen language is open to debate, but whatever it was, they certainly were not prepared to co-operate with the English detective.

During the two days he was there, the only development he made was by way of a severe case of gastroenteritis, which he put down to the ‘horrible foreign food’ he was forced to eat. What he didn’t know at the time, however, was that Hammond had left Paris the very night that he had arrived, and had made his way to Belgium, from where he then escaped to America. In other words, ‘someone’ must have tipped him off that Abberline was hot on his trail. Who this someone was, we will probably never know!

A very angry and frustrated Inspector Abberline returned to London, refusing point blank to speak to reporters, who by this time had started to get a whiff that something important was going on, as by now, his team at Scotland Yard had arrested several other telegraph boys and were holding them for questioning. Any reporter worth his salt knew, without a doubt, that they would not do this if it were just in connection with petty theft from the Central Telegraph Office. Unbeknown to the reporters, and it seems everyone else apart from the investigating team, more of those arrested had now also made statements, and named Somerset as a regular visitor to 19 Cleveland Street.

Abberline was getting fed up with chasing suspects, who were, in his eyes, obviously being tipped off by some mysterious third party, so he decided to proceed with the prosecutions on the evidence that he and his team had collected thus far. Two days later he presented his case to Sir James Monro against Hammond, the telegraph boys who acted as his willing accomplices, and a variety of gentlemen whom the boys had named. Monro seemed more than happy with the prospective prosecution, which had done exactly what he wanted, taking the case forward whilst excluding the really big names. Monro was sure that this would ingratiate him with his superiors, or so he thought, because when he decided to go ahead with the prosecution, he was suddenly faced with a solid wall of resistance.

The Home Secretary demanded to see the notes on the investigation and within hours, threw them back at Monro, telling him that the case was very weak indeed, and in his opinion should be dropped forthwith. When Monro and Abberline both appealed against this, the Home Secretary was joined by the Attorney General and the Lord Chancellor, and if that wasn’t enough, the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury himself, also joined in the chorus of disapproval.

When Inspector Abberline was informed of this decision, he was absolutely furious and suggested to Monro that they should ignore these dissenters and go ahead with their case against Somerset and his cohorts; they had a strong case as far as he was concerned, with witness statements to back it up. Monro, however, had already been warned of the political implications right from the start, and even though he felt as strongly as Abberline on the issue, he also knew that his job could possibly be in jeopardy if he did not toe the line on this case.

During the following few weeks, friction mounted even more, as Abberline allegedly threatened to resign from the police force if the case was going to be swept under the political carpet, as he put it. One of the main reasons that Monro had inducted Abberline into the Cleveland Street case, apart from him being an excellent detective, was because he thought he was going to be an easy ride, a yes-man, who would do exactly as he was told. By this time, however, Monro was discovering a completely different side to Inspector Abberline, a rebellious side that he never knew existed.

While all this was continuing, the telegraph boys were still being questioned, and by 19 August, another new name had been thrown into the arena. This was George Veck, who had at one time also worked for the Telegraph Office, but had been fired from his job for improper conduct with some of the telegraph boys. Veck had never been charged with any offence regarding this, but after leaving the Telegraph Office, he became a close acquaintance of Hammond, allegedly procuring more young boys whilst posing as a vicar.

Abberline immediately issued an arrest warrant for Veck, and along with four officers from his team, made a dawn swoop on Veck’s London lodgings. The only person there when they arrived was a 17-year-old youth, who they found in a large double bed on the first floor. The youth told them that Veck was away in Portsmouth and would be returning that morning, via Waterloo Railway station.

Inspector Abberline and his team wasted no time in rushing to the station, where they arrested Veck as he alighted from the Portsmouth train. They took him directly to Scotland Yard, where he was questioned and searched. Among his possessions, they found several letters, two of which were from someone named Algernon Allies, whom, according to the letters, had been very ‘close’ to Somerset. Allies was interviewed at his parents’ home in Sudbury, Suffolk, where he admitted to having a sexual relationship with Somerset and receiving money from him. He also admitted working at Cleveland Street for Hammond.

Now armed with this extra evidence, Abberline decided he was not going to allow himself to be intimidated by his superiors any longer, and to take matters into his own hands. On 22 August, he called, unannounced, at Lord Somerset’s home, where he proceeded to interview him again. But Somerset proved more than a match for the detective, and refused to answer any more questions until he had his solicitor present. Abberline could do nothing but agree, and gave him twenty-four hours to attend his office at Scotland Yard, along with his solicitor. Somerset, however, never did go to the Scotland Yard meeting, and left that same day for Bad Homburg vor der Höhe, in Germany, where the Prince of Wales was then holidaying.

While Somerset moved around Germany, from Bad Homburg to Hanover, apparently purchasing horses for the Prince of Wales, the trial in England was getting ready to begin. Monro was relatively happy that no big names were firmly attached at this point, and Abberline saw the case as foolproof; one that he was sure would re-endorse his reputation and if he was lucky, ones that he might even be able to surreptitiously bring a name or two into before he was stopped again.

Finally, on 11 September, Newlove and Veck, alongside a number of the telegraph boys, were committed for trial. The big surprise of the day, especially for Abberline, was that Lord Somerset’s solicitor, Arthur Newton, suddenly announced that his firm, who was being paid by Somerset, would be handling Newlove and Veck’s defence. If that on its own wasn’t enough to prove Somerset’s involvement, then nothing was, but still the message came down the line that his name was not to be pursued in this case.

On 18 September, Newlove and Veck pleaded guilty to indecency. Newlove was sentenced to four months’ hard labour, and Veck to nine months. The judge in the trial was Sir Thomas Chambers, a former Liberal Member of Parliament who had a reputation for leniency, but it was never expected by anyone that even he would dish out such lenient sentences as this. The telegraph boys were also handed out sentences that were considered by both the police and the general public to be far too mild. Even the assistant public prosecutor, Hamilton Cuffe, said that the trial was a travesty of justice, but when asked to elaborate on his comments outside the court, he declined, as he ‘Didn’t want to miss the 6.15 p.m. train from Waterloo’.

Charles Hammond, meanwhile, still lounged somewhere, either on the continent, or in America. Abberline was still eager to bring him back to face trial, but the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, made it absolutely clear that no extradition proceedings should be instigated against him, and the case against Charles Hammond was quietly dropped.

After the trial had ended, and presumably thinking that he was now safe, Somerset returned to Britain on 30 September, apparently to attend horse sales at Newmarket. As soon as Abberline got wind of this, he had him followed night and day, wherever he went. Abberline ordered the surveillance to be purposefully open; he wanted Somerset to be fully aware at all times that he was being watched. Why Abberline used this method of surveillance, no one seems to know. One theory was that Abberline thought by doing it this way, he would break Somerset down, and hopefully induce him to confess to his role in the scandal. Others alleged that, by this time, Abberline personally hated Somerset so much for escaping justice in this case that he simply decided to harass him in every way he could.

On 18 October, Lord Salisbury, whilst on his way back from France, received a telegram from Sir Dighton Probyn VC, the Prince of Wales’ comptroller and treasurer, asking him to meet him urgently. Lord Salisbury said later that, thinking the meeting to be about Foreign Office business connected with the Prince of Wales, he agreed to meet Probyn for a few minutes in a private waiting room at the Great Northern Railway station, where he would be waiting for his 7 p.m. connection home.

It was at this meeting that Probyn warned Lord Salisbury that Lord Arthur Somerset, extra equerry to the Prince of Wales’ eldest son, Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence, was about to be arrested for gross indecency at a male brothel at 19 Cleveland Street, London. The day following this meeting, Somerset fled the country to France. Did Newton warn Somerset that his arrest was imminent? This was denied by Lord Salisbury and the Attorney General, Sir Richard Webster. The Prince of Wales wrote to Lord Salisbury expressing satisfaction that Somerset had been allowed to leave the country, and asked that if Somerset should ever show his face in England again, he would remain unmolested by the authorities; however, Lord Salisbury was also being pressured by the police to prosecute Somerset. On 12 November, a warrant for Somerset’s arrest was finally issued. By this time, Somerset was already safely abroad and the warrant caught little public attention.

This now left the question open as to Arthur Newton’s relationship with Lord Salisbury. Had the Prime Minister himself passed this privileged information on to Newton, for the express purpose of it then being relayed to Lord Somerset? After all, it was Newton who had supplied the money that Charles Hammond used to escape to Belgium and America, and it was Lord Salisbury who had said that he did not consider it appropriate for an official application to be made for Hammond’s extradition.

Arthur Newton was subsequently tried for conspiracy to pervert the course of justice, after he was caught attempting to pay off the telegraph boys to go abroad before they could testify. He was found guilty and sentenced to just six weeks’ imprisonment; another ridiculously lenient sentence!

As more names and rumours started to emerge, the young editor of the North London Press, Ernest Parke, decided to publish the names of Somerset and Henry FitzRoy, Earl of Euston, hinting that ‘They had been allowed to leave the country and thus defeat the course of justice, because their prosecution would disclose the fact that a far more distinguished and higher placed personage than themselves was involved in these “disgusting crimes”.

Parke wasn’t any different to most newspaper editors: he saw a good story and decided to cash in on it. These names and the rumours surrounding them were being widely spread in Britain, whilst on the continent they went even further and printed allegations in their newspapers that Prince Albert Victor, the heir to the throne, had been a regular visitor to the Cleveland Street brothel.

The Earl of Euston, however, wasted no time in taking legal action against Parke, suing him for libel. He admitted that he had been to the premises, but not for the purpose that Parke had alleged. He claimed that his reason for visiting the Cleveland Street house was because he had been misinformed that the house was a sort of ‘theatre’, where one could see naked women posing motionless – all very arty and not at all against any law. As the case continued, both sides tried their best to implicate the other, calling long lists of witnesses. At the same time, the rumours about Prince Albert Victor’s involvement intensified. Whether this actually worried the prince or not is difficult to judge accurately, for he left the country just about the same time as the trial started, for a royal wedding in Greece and an extended tour of India, which would last the best part of seven months.

Parke called every witness he could muster to try to prove his allegations against the Earl of Euston, but found the odds stacked against him with hardly a word he was saying being believed. He constantly mentioned other evidence which would prove his allegations without a doubt, but when pressed he said he could not divulge this without betraying his source. As everybody knows, rumours and unfounded allegations are not enough to convict anyone in a courtroom it was now a case of ‘put up or shut up’. The name that was then being bandied about was none other than Inspector Abberline. Could it have possibly been him? Whoever it was, it certainly didn’t help Parke, for he was found guilty and sentenced to a year in prison for libel.

The Cleveland Street scandal, as it had come to be known, ended with minnows, such as Newlove and Veck, a handful of telegraph boys and Lord Somerset’s solicitor, Arthur Newton, all being found guilty of somewhat minor infringements of the law and handed miniscule and ridiculous sentences. Then there was, of course, the newspaper editor, Ernest Parke, who received the largest sentence of them all, for his terrible crime of daring to name names. As for the names themselves, as we now know, none were ever brought to trial.

In February the following year, Henry Labouchère, the Radical MP for Northampton, took an interest in the case, and began to investigate Salisbury’s role in helping Somerset escape justice, suggesting that Lord Salisbury and several others should still be prosecuted.

Labouchère made a long speech in the Commons, accusing Salisbury of a criminal conspiracy to defeat the ends of justice. The house settled back in awed silence, as Labouchère continued his devastating and largely accurate account of what had happened, and ended with stating that in his opinion, ‘The government wish to hush this matter up’. Labouchère refused to accept the Attorney General’s defence of Salisbury, saying that he didn’t believe either him or the Prime Minister. The speaker of the house warned Labouchère on two occasions, and finally rose and called Labouchère to order, suspending him from the Commons for a week. Labouchère’s resolution for an inquiry was meanwhile defeated by 206 votes to 66. At the end of the vote, Labouchère rose again and pointed to his fellow Northampton MP, the atheist Charles Bradlaugh. ‘My honourable friend was suspended for disbelieving in God,’ he joked, ‘and I am suspended for disbelieving in Man.’

Lord Salisbury continued his career with complete disregard to Labouchère’s accusations. Somerset, meanwhile, searched for employment in Turkey, Austria and Hungary, and then went off to live quietly in self-imposed and comfortable exile in the south of France with a companion, until his death in 1926.

The other, and certainly the most famous name, to be bandied about with regard to the Cleveland Street scandal was Prince Albert Victor, the Duke of Clarence. He was away in India during the trials, and only returned to Great Britain in May 1890, but that, of course, would not have prevented him from visiting the Cleveland Street brothel during the previous years.