Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

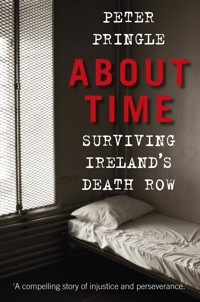

Law and justice are not always one and the same. On the 27 November 1980, Peter Pringle waited in an Irish court to hear the following words: 'Peter Pringle, for the crime of capital murder … the law prescribes only one penalty, and that penalty is death.' The problem was that Peter did not commit this crime. Facing a sentence of death by hanging, Peter sought the inner strength and determination to survive. When his sentence was changed to forty years without remission he set out to prove his innocence. Fifteen years later, he is finally a free man. This is his story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 370

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

I dedicate this book to my children and grandchildren – and to set the record straight

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Prologue

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Postscript

Plate Section

Copyright

Acknowledgements

This book comes out of my desire to tell my story. I struggled to prove my innocence and I regained my freedom with the help of a great Human Rights lawyer, Greg O’Neill. I remain very grateful to him and to all my friends and family who stood by me. Thanks to Lorna Siggins for her article in The Irish Times; to Ronan Colgan of The History Press for expediting the publishing process; to Aonghus and Beth for their valuable and painless editorial assistance; to the legal department for their in-depth examination and advice.

My thanks to Sunny for her support and love.

Prologue

Death cell, Portlaoise Prison, December 1980

‘I hear that at least two of us will have to help at his hanging.’

‘I heard that too, wonder will they ask for volunteers or will we be ordered to do the job?’

‘Either way we would have to be paid extra wages or a bonus.’

‘That’s right, they’d have to make it worth our while.’

‘What would we have to do?’

‘When he drops through the trap door of the gallows we’d be underneath ready to pull on his legs to make sure his neck is broken.’

‘There’d have to be one for each leg.’

This discussion by three jailers was conducted in my sight and hearing as if I did not exist. ‘Happy Christmas, Peter,’ I whisper softly as I try to distance myself from the reality of being in the death cell.

1

I was born in Dublin in 1938. During the war, when I was about 4 years old, I would watch the searchlights in the sky at night and it was very exciting. They were operated from the army barracks at Portobello, nearly a mile away from our house. My pal Nancy, who lived next door, was the same age and we decided that we wanted to see the searchlights up close. So that night, after we were put to bed, we each climbed out of the window and down the drainpipe and headed off, hand-in-hand, to find the barracks. We got into the barracks area through St Mary’s College grounds, which were adjacent to the barracks, and hid in some bushes to watch the searchlights. We fell asleep there and were found by the sentries who brought us to the canteen where they gave us cocoa and biscuits.

Meanwhile, our parents had discovered that we were missing and had frantically organised a search. They and the army notified the police and we were soon returned home safe and sound. I couldn’t see what the fuss was about. Our parents were so relieved to have us home safe and sound we were not punished – but they checked on us more often when were were put to bed.

My older sister Pauline always looked out for me and my younger brother Pat, especially if some other kid tried to bully either of us. I, in turn, looked out for Pat. That’s how it was with brothers and sisters, and not just our family. We built a hut made from scraps of timber in the middle of the bushes. In the autumn when apples were ripe we would go on an expedition to ‘box the fox’, which is what raiding an orchard to steal apples was called, although we did not think of it as stealing. Sometimes we would be chased by an irate house owner and have to run hell for leather to get away. When we got back to our hideout we would feast on the apples, sharing them with the other youngsters.

If we had difficulty with doing our school homework Dad would look at the problem. He would not solve it for us but would show us the method for solving it and leave us to sort it out ourselves. Then he would look at our result and question us as to how we had resolved it. At the time, I did not really appreciate his wisdom.

My Dad rented a bog on the Featherbeds, an area of the Dublin Mountains to the south of the city. He would go up there on Saturdays and Sundays and cut the turf. Sometimes he’d bring me with him, on the crossbar of his bicycle as far as Rathfarnham, where we would board a big turf lorry, bike and all, and be driven the rest of the way up to the Featherbeds. While Dad was cutting turf my job was ‘footing the turf’, stacking it in a special way so that the wind would dry it out. We would light a fire and boil tea and eat our sandwiches for lunch. I loved being in the mountains. Come evening time, we would travel home by bike as it was all downhill. We seemed to whizz along the road and be home in no time. When the turf was all cut and dried and ready to be taken home, the turf lorry would collect it and bring it to our house and tip it in the back lane. Our neighbours and all the kids on the street would help to bring it into our back yard where my Dad would stack it properly. Then there’d be a big party, with Guinness and food for the men and lemonade and cakes for the kids – and pennies too.

My grandfather lived in County Kildare, near Rathangan. He was originally from Dublin, but left the city when they started building outside of the two canals. He reckoned the city was getting too big. He and my grandmother had a small farm and every summer I looked forward to going to them on holidays. It was magical for me, being in the country and enjoying their country ways. They had two cows, a pony, pigs, hens, geese and ducks. There were fields and woods to roam, and a river at the bottom of the big field. Grandmother made homemade bread, cakes and butter. And in the evenings around the fireplace, it was so warm and snug. Listening to the stories and local news I got ever more drowsy. I would then be carried down to the room and into bed, to dreams wrapped in eiderdown quilt and not stirring until daylight. Sometimes I would lie in bed and listen to the chug, chug, chug of the barges as they passed along the canal about a mile away. The sound of the barge got louder on the night air as it came closer, and then it would fade away into the distance. And I would dream of its journey and of travelling on it.

Sometimes my grandparents told stories about the Fairies. And they believed in their existence too. Each night before retiring, Grandmother put a glass of milk and a plate of cake or scones in the window for the Fairies. And it was always empty in the morning. I remember one time walking in the woods with Grandad, and we came on a fox’s covert. He pointed it out to me and told me that this particular opening was also the entrance to the Fairy world under the ground. The Fairies, or ‘Little People’ as they sometimes called them, lived underground and in the hillside and one must always respect them. This was wise, as the Little People could be lethal if they were upset or treated with disrespect. Grandad told me to keep the memories and not lose sight of the important things handed down to us through the generations.

I remember one time Aunt Mainie, who lived with my grandparents, had to visit the dentist in Kildare Town, which was several miles away. The evening before, Grandad brushed down the pony, polished the harness, and shined the buckles and the brass rails on the trap in preparation for the journey. We were up early for breakfast, and then I went with Grandad to get the pony ready for the trip. When he had been harnessed to the trap I held him while Grandad went to put on his Sunday suit. Grandmother and Aunt Mainie were all dressed up too, hats and gloves and all. The trap was a two-wheeled light cart entered through a door at the back. Seating was along each side, passengers facing inwards. Grandad sat to the front on the outside and I sat opposite him. Grandmother and Aunt Mainie sat to the back and away we went, Grandad gently clucking to the pony to start him trotting. After a few miles, when the pony had settled in to his task, Grandad passed the reins to me while he filled his pipe and lit up. Satisfied that I was doing alright, he settled back and enjoyed his smoke while I tried to appear casual driving along, especially if we met anyone on the road. It was the most exciting event of my life up to then.

In Kildare we watered the pony at the horse trough in the square. Then Grandad tied him to a tree and put a nose bag of oats around his neck and the pony munched contentedly. Grandmother had gone with Mainie to the dentist, and I strolled about the town with Grandad. He met lots of men he knew and I was introduced to them. Two of them even slipped me a sixpenny piece with a wink. After the dentist we all went to the hotel for lunch but Aunt Mainie was only able to sip a bowl of soup.

I don’t remember much about the trip home. With all the excitement of the day, the motion of the trap and the rhythm of the pony’s hooves, I fell asleep and only woke up as we were turning into the farmyard. But I helped Grandad un-harness the pony and wipe him down and stow the harness before going up to the house for supper. I don’t remember going to bed either, but I slept the night through. The summers passed quickly. Then it was back to school.

About 1946 there was a teachers’ strike, and my pals and I thought we would be off school and have great fun. But my parents had other ideas for me, to my great disappointment. The strike was by lay teachers, which meant the Christian Brothers schools remained open, so my parents enrolled me in St Laurence O’Toole’s in Seville Place on the opposite side of the city. On my first day, my Mum took me on the bus to show me the way and collected me after school. That evening I was asked if I could make the journey on my own. I said that I could, because I thought this was expected of me. Although I was afraid, I kept my fear to myself. No doubt if I had spoken up my Mum or Dad would have escorted me, or sought a different school for me.

Thereafter, I would walk to Kelly’s Corner and take the number 20 bus right across the city. I used to sit upstairs, in the front seat if possible, feeling much older than my 7 years. Walking down Seville Place to the school from the bus, I had to go under a long railway bridge with separate arches for traffic and pedestrians. It was halfdark and I was in strange territory. I braced myself, worked up the courage and ran as fast as I could through the long archway as though my life depended on it! On my second day at school the class bully picked on me and I had to fight him at lunchtime behind the bicycle shed in the yard. The other kids gathered around and I knew that I must not show my fear. In desperation, I fought like mad and to my surprise the bully gave up quickly. After that, I was accepted by the other kids and my time was happy enough at that school. I was big for my age and quickly learned not to back down. Most times I didn’t have to fight. I was glad of that as I never liked fighting.

At that time, there was a lot of horse-drawn traffic in Dublin. The Post Office main sorting depot was in Amiens Street, which was on my route home from school. Instead of taking the bus I’d walk to the sorting depot, and when one of the post wagons, loaded with mail bags and drawn by two horses, trotted out from the depot heading across town I would ‘scut’ on the back of it and get a free ride across the city. Sometimes, someone would yell, ‘Scut behind! Lash the whip!’ and the driver sitting high in his box at the front would crack his long whip behind him to scare me off the back of his wagon. As soon as I heard the yell I would crouch down as low as possible, only straightening up again after hearing its ‘crack’ above my head. It was exciting, and I loved it. And I managed to save my bus fare to buy toffees, and sometimes cigarettes. I was rapidly becoming streetwise and learning to take care of myself.

When the teachers’ strike ended my parents got me into Synge Street Christian Brothers School, which was within walking distance from home. I enjoyed the junior classes, but as I advanced through the primary school I had some nasty experiences with Brothers who seemed to enjoy punishing us. At the time, corporal punishment was accepted in schools. One Brother had coins stitched inside his leather strap and being slapped by him was tough. Sometimes he would take a boy by the ear from his desk to the front of the class, grab the short hairs above the ears and lift him off the ground by the hair. When he did it to me it was hard not to scream or cry. But when I saw that that was what he wanted I gritted my teeth and tried to stay silent, no matter what pain he would inflict on me.

The Brothers were not the only hazard in that school. The boys tended to pal together in groups, or gangs, for self-preservation. The rivalry between groups was mostly friendly, but occasionally there would be a fight. On one occasion I was picked on by a boy called Mac from another group. I had no option but to fight him. We were caught and punished by one of the Brothers, who gave us an extra leathering because neither of us would blame the other. No matter our differences, we had to stand together when faced by a brutal Brother. We became friends thereafter, and I had no more trouble.

Some days I would skip school, happily wandering the streets or through the park at St Stephen’s Green. This was called ‘mitching’. But when I returned to school I’d be behind the rest of the class in my studies, which brought even more trouble from the sadistic Brothers. Ultimately I decided it was better to attend and try to stay unnoticed, rather than give them an excuse to focus on me.

Our dog Spot was a floppy-eared mongrel, black with a white spot on his chest. He’d follow me most of the way to school and meet me on my way home. When I crossed Richmond Street he would usually turn back. But one morning he came after me and was knocked down by an army truck. I ran back to him and held him in my arms, crying my heart out. Soldiers got down from the back of the truck laughing, and I became fierce angry. I brought Spot to the veterinary hospital across from where the accident happened. But the poor thing was too badly injured and had to be put down. I was devastated.

I became an altar boy in our local church in Rathmines. There was a priest there who was shell-shocked from the war and who was eccentric, especially in his speech. His voice could range from a quiet whisper to a loud shout almost in the same sentence – and he did not seem to be aware of this. The other mass servers were scared of him. But I liked him, and was chosen to serve him at mass a couple of times each week. He was always allocated to say his mass at a side alter, and when very few people were in church. This often meant that I’d be a half hour late getting to school, which the Brothers forgave because I was serving at mass. The priest sometimes gave me a shilling after mass and that was a mighty bonus as far as I was concerned, considering that I could get in to the cinema for six pence and the Saturday matinée for four pence.

‘Any oul rags, bottles, or bones? Any oul rags, bottles or bones?’ called out the ragman as he came into our street with his horse and cart.

We loved seeing him come, and we would run to our houses to see if we could get anything for him. ‘Mum! Have we any old rags for the ragman?’

‘Get out of that and don’t be annoying me, there’s nothing for that old fella unless I give him the rags off my own back! Go on out to play!’ But we would search in the garden shed and maybe find a few empty bottles and the ragman would pay us with a toffee apple or maybe a windmill. This was a sort of windmill on a stick, which rotated if we ran along holding it up to the wind.

We would not give him jam jars because they were too valuable to us then. Glass was scarce due to the war, and we could get into the Saturday matinée at the local cinema for two pence and two large jam jars. Without our jam jars it cost four pence to get in. We had two cinemas near us on Rathmines Road, the Stella and the Princess. The latter was commonly known as ‘the Prinner’ and was the only cinema locally to accept jam jars in part payment for entry to the matinée on Saturday. The queue outside the Prinner was always long – a crowd of laughing, talking, yelling youngsters holding tight to their jam jars. Johnny, the usher, was a tough little Dubliner who could control any mob of chisellers. When the concertina gates were opened, Johnny appeared in his tacky maroon uniform and stood at the head of the queue, hands on hips, and let out a roar. ‘Quiet!’

There was instant silence. He proceeded along the queue, carrying a large basket. And as a kid placed his jam jars into the basket, Johnny handed a chit to the kid in exchange. When all the jam jars were exchanged for chits and he had deposited the basket inside, Johnny would allow us into the cinema. Once inside, there would be a mad rush to get seats. Everyone wanted to get up on to the balcony, and that’s where the first of the queue went. If we did not make the balcony we made sure to be near the back and under the balcony. Nobody wanted to sit downstairs in front of the balcony, because sometimes kids in the front row of the balcony would pee over the front instead of leaving their seats to go to the toilet in case they would either lose their seat or miss an exciting part of the film. Johnny had his work cut out keeping order in the darkness of the cinema, as he ranted up and down the aisles flashing his torch along the rows. We had an economic crisis when glass became plentiful again and the value of the empty jam jars fell, first to one penny for a large jar and ultimately to no value towards entry into the Prinner.

When rationing ended and fruit could be imported again, the excitement of seeing my first bananas and oranges was wonderful. Sometimes, as banana lorries were stopped at traffic lights kids would climb up the back and throw bunches of bananas off to the other kids, who would gather them up. Then at the next corner the bananas would be shared out. We never thought about the dangers involved in such an escapade.

2

Just before I turned 14 I left school and went to work. Actually, I didn’t just ‘leave’ school, I had no other option. One of the Christian Brothers had a boy out in front of the class giving him a beating, while the rest of us sat petrified in fear. To everyone’s surprise, and none more than myself, I shouted out, ‘Leave him alone!’

The Brother left him alone sure enough, only he called me out instead. I was terrified at what I’d done and knew I was really in for a trouncing. He grabbed me by my sweater and as he drew back his fist to punch me I suddenly realised that I was as big as he was and in desperation lashed out and sent him flying. He stumbled back, more in shock than from my wild punch, and banged into the blackboard, falling over it and bringing it down with him. The class gave a great cheer, a frenzied release of tension. There was a moment when I felt great, as the class continued to cheer and beat on the desktops. The Brother scrambled on the floor trying to get untangled from the blackboard and to his feet. I could see his face bloated red with anger and I knew I had to get out of there. I quickly gathered up my books and headed for the door, with him screaming as he scrambled to his feet, ‘Quiet! Quiet! Get back here Pringle!’

I kept going. But with the front door to the street in sight, I was caught by the head Brother. He wanted to know what a boy was doing in the corridor leaving the school during class time. When I told him I was leaving for good he put his arm around my shoulder and walked me to the door saying he was sorry to see me go as he was sure I’d been happy in the school. This puzzled me as it was the first time he’d ever spoken to me and I was always careful to stay well out of his way. As we got to the door he said he wanted to give me good advice as I headed out into the world. He told me to say my prayers and to beware of loose women! And that was it. I was free. I walked away from the school towards home, exhilarated and smiling as I remembered the expression of shock on the face of the Brother as he fell over. But then I thought about facing my parents and that took the smile off my face. I looked in every shop window along the way and stopped to watch a barge go through the canal lock.

When I got home I told my Mum what happened. She said we would wait until Dad came home and let him sort it out. Dad came home and we had dinner, but my stomach was tight as I waited for the inevitable.

‘Tom, Peter has something to tell you. Go ahead Peter.’

I then told him what had happened. As his face darkened, I explained how terrible it was at that school and that I was never going back there. He sat a few minutes looking at me and my Mum as he considered the whole thing. Turning to Mum he said, ‘Maybe we can sort this out if we go speak to the Brother.’ Before they could take that idea any further, I insisted again that, no matter what, I would not return to that school. After more discussion and attempts to change my mind, he finally said, ‘Well, if you won’t go to school you’ll just have to get a job.’

A few days later he spoke to a friend and I started work the following week.

My first job was with a wholesale tobacconist and confectioners in the city centre. I started work at £1 10s per week, gave up £1 to my Mum and had 10 shillings for myself. In a period of unemployment and emigration it was good to have any kind of work. Everyone was friendly and I quickly became used to the job. The mornings were usually spent packing goods on the shelves. Afternoons were hectic as orders came in and had to be prepared for delivery the following morning. In my second week the boss asked me why I did not cycle to work. When I told him I did not own a bike and was saving to buy one, he went in to his office and came out with an order to a bicycle trader. He said I could pick myself a bike and he would deduct the payments from my wages. I bought a bike at trade price and was well pleased with myself. We agreed on 10 shillings a week. The following week when I got my wages there was still £1 10s in the envelope. I went to the boss and asked if he had forgotten to deduct for the bike and he told me he had given me a 10 shilling raise. Cycling to work in the mornings was mostly downhill and I could fly along. Going home in the evenings I had to pedal hard uphill, except when I could catch on to the back of a truck and be pulled along. The excitement of that was greater than any thought of its danger.

When I started work in 1952 there was a lot of poverty in Ireland. I remember seeing the unemployed marching in the streets, demanding work. People were poorly dressed, and poorly paid. The unemployed had barely enough food to feed their families. The pawn shops were thriving businesses, and it was not unusual for the Sunday clothes to be pawned on Monday and redeemed again on Saturday for mass on Sunday. Bellmen, as they were called because their horse had a bell around the neck which rang as it moved, went around with their horse-drawn carts selling coal by the stone (14 lbs) or by the bucket. Very few people could afford to buy a bag of coal. Grocery shops sold loose tea by the ounce, and butter likewise. Beef dripping was sold and spread on bread instead of butter and was often referred to as ‘bread and dip’ when the dripping was heated on a pan. My Dad used to repair our shoes when the soles and heels wore out, by placing the shoe on a last and fitting new soles and heels by hammering in little nails. Then he trimmed the leather with a knife and dyed the edges. When he had finished, the shoes looked almost new again. Nobody I knew had a telephone or a car. One man on our street had an old motorbike, but otherwise the main means of transport was the bicycle if one was lucky enough to have such a luxury. Going by ‘shanks’ mare’, or walking, was the norm.

After a few months I was able to buy a rucksack and hiking boots and I took up hill walking. This quickly became my favourite way of spending the weekends. I joined the youth hostelling association, hiked to all of the mountain ranges in the country and walked them all. I developed a strong love for the west of Ireland and often headed off from Dublin to climb the Twelve Bens in Connemara.

The following summer, when I was 14, I had my first holiday from work. I wanted to hitch hike to Kerry and west Cork to climb the mountains and visit some historical sites I was interested in seeing. Two of my pals from the neighbourhood, Mike and Seán, agreed to travel with me, and the three of us were to leave on the Saturday. My parents accepted my going away hiking at weekends, but heading off for two weeks caused them serious concern. After long negotiations, however, they agreed to the holiday. But three days before the departure date Mike pulled out and on the Friday evening Seán told me he couldn’t go either. I swore each of them to secrecy and on Saturday set off on my own, my parents still believing I was to join up with the two lads down the road.

The first day I hitched to Bansha in County Tipperary. I walked to the hostel at Ballydavid Wood and stayed there that night, and in the morning I walked to Bansha for Mass. The priest gave a long sermon, his theme being ‘Do unto others as you would they do to you’. On the walk back to the hostel it began to rain heavily. A car came along and I tried to hitch a lift. It was the priest. Not only did he not stop, but he drove through a pool of water, splashing me. My legs were soaked. I became angry with the priest and his total disregard for what he had just preached, deciding there and then that I was finished with the Catholic Church, God and all that nonsense, as I saw it then. That decision seemed to me to be in harmony with my being away on holidays on my own, and I felt good within myself.

Back at the hostel I changed clothes, collected my rucksack and set off up the slopes of the Galtee Mountains. I walked the mountains all that day, climbing Galtee Mór, the highest point, before heading down the far side to the hostel at Mountain Lodge, where I stayed that night. The next morning I sent my parents a postcard explaining that I was on my own and doing well and asking them not to worry. I went on my way and hitched to Kerry.

I climbed Mangerton and Carrauntoohil, the highest mountain in Ireland. The day was clear and the scenery was magical and I felt like I was achieving something great. I stayed in a hostel near Killarney where I met a girl who wanted to see the Gap of Dunloe, so we hired ponies and rode up to the top of the Gap. She was a nice girl and fun to be with. When we got back down and returned the ponies my behind was very sore. We explored the area together on foot for a couple of days, courting a little but nothing more than that.

Next day, I headed off alone to explore the Beara Peninsula. I had read about O’Sullivan Beara, the seventeenth-century chieftain who had to leave his homelands after the Irish were defeated in the Battle of Kinsale at Christmas 1601. He set out with one thousand of his people – warriors, women and children – to march to Leitrim to join with O’Rourke of Breffny, who was still undefeated. They were harried and attacked all along the way, with less than thirty surviving to reach their destination. I was fascinated by the story and wanted to walk the peninsula where they had lived. It is rugged country and very beautiful. Walking the hills with the Atlantic to the north and to the south was a great experience for me, and I imagined how it must have been back then when it was covered in forests.

Heading north, I made a stop at Foulksrath Castle, County Kilkenny, which was also a hostel. I had heard that this sixteenthcentury Norman castle was haunted and so wanted to experience staying there. By this time I had very little money left, so as opportunity arose I gathered a few potatoes and carrots from a garden as I passed by and cooked them for my dinner in the hostel later that evening.

There were four other young men staying in the hostel that night. The men’s dormitory was two floors up a winding stone stairway, with the women’s another floor above. As we were in our dormitory getting ready for bed one young man went back downstairs for something. On his return he told us that he had met a beautiful young woman coming upstairs as he was descending. She had long fair hair, wore a long white nightdress and held a candle to light her way. As he stepped aside to let her pass she smiled as she continued upwards. We assumed she, and perhaps some friends, had been late arrivals, which explained why we had not seen her earlier. The following morning at breakfast, the lad who had seen her told the old woman who ran the hostel. Smiling quietly, she said, ‘That was herself, she is here all the time’, as if it was nothing unusual. Later she explained that ‘herself’ was the ghost of the castle. I stayed a second night in the hope that I might meet her, but she did not show herself to me.

I was nervous as I approached the house on my return from the two-week break. I accepted that I was wrong to have gone off as I did but knew also that I had to do it. My folks gave out to me, of course, but were glad I was home safe. They had finally come to accept that I could look after myself, and I think they were actually a little proud of that. I resumed work on Monday and life returned to normal, although my friendship with Mike and Seán was changed and I did not hike with either of them again.

When I could afford it I would take the boat to Holyhead, leaving on Friday evening directly from work, to spend the weekend on the Welsh mountains. I bought most of my hiking gear in Wales as prices were much lower than in Ireland. I’d arrive back in Dublin in time for work on Monday morning. Scotland was also a favourite place but on my money I got there much less frequently than to Wales. As I gained more experience and better equipment I either slept out or in huts I had located in the forests. Sometimes I walked with a friend, but quite often I went alone. I liked being on my own in the mountain vastness and enjoyed the sense of self-sufficiency.

Around this time I was initiated to full sex by an older woman whose husband was working in England. At my Mum’s suggestion I used to do errands for the woman on occasion. One day, when I brought her groceries from the shop, she answered the door in a dressing gown. And when I had put the box of groceries on her kitchen table she put her arms around me and kissed me. Before I knew it she was leading me to her bedroom. Then she was naked and undressing me, caressing and fondling me. And I was touching her. Soon we were on her bed and she showed me how to make love. At first I was frightened and really did not know what to do, but she soothed and guided me. And it was wonderful. She was sweet, kind and fun. It was like a whole new world had been opened to me. I was sure I was in love with her. She swore me to secrecy, otherwise she would never be with me again. Actually, we were only together on three other occasions over the next few weeks, as her husband came home soon after and they went to live in England. When she left I missed her, and was broken-hearted for a while. I had girlfriends from time to time, and liked being with girls. But I found that being with women a little older was better, especially sex-wise.

At work I did odd jobs as well as helping make up the orders for the van to deliver. Sometimes I would go with the van as helper and for me that was the best part of the job. Dermot the driver was quite a character and I loved being on the rounds with him. He had a caustic Dublin wit and cynicism, never short of a comment or retort no matter the occasion. Each day after his lunch Dermot would take a nap on a chaise longue in his kitchen. ‘That’s what the aristocrats do for their digestion and if they can do it so can I!’ Dermot taught me how to drive. At lunchtime he used to drop me home before heading to his own place. But one day he went via his house and got out of the van, telling me to drive myself home and pick him up an hour later. That was how I started to drive regularly. I was 16 and eligible for a driving licence, which I got later.

One afternoon on our rounds we went into Tommy Ryan’s pub on Haddington Road so Dermot could listen to a horse race on the radio. He had a pint and I had an orange. A tall man swept in dramatically, called for a pint and pulled a stool into the middle of the room, greeting everyone in a loud voice. He had on a gabardine coat and wide-brimmed hat. He knew Dermot and asked, ‘Who’s your young friend?’ introducing himself as ‘Paddy’. He went on to regale the company with stories and jokes and had everyone laughing, including the publican. When we left, Dermot told me that was Paddy Kavanagh, the poet. When I made a comment about his unusual behaviour he said, ‘Ah, you don’t understand. He’s a poet.’ He went on to explain that Paddy was most likely broke and by entertaining the company he ensured a flow of porter. I was surprised at the respect and even love shown to Paddy by everyone in the pub, and only later understood Dermot’s comment about being a poet. To be a poet in Ireland engendered respect, awe and allowance for eccentricity. Poets have always been very important to the Irish psyche throughout our history.

History was very interesting for me. I was an avid reader and the library and second-hand bookshops were my source, as well as my Aunt Molly. A real rebel, she lived her life according to her own dictates, having run away from home to join a travelling show to be with her lover. Whenever she was in Dublin she visited us, bringing me books by such writers as Nabokov, Dickens, Tolstoy, Faulkner, Steinbeck and Hardy. We would then discuss those books on her next visit. I read anything I could about Irish history and learned something about the 1916 Rising and the struggle for independence. Of the 1916 leaders, James Connolly and Thomas Clarke made the biggest impression on me. I was inspired by Connolly for having organised the Citizen Army for the defence of the working class, and Clarke for his dedicated perseverance in the struggle. I admired people like Tom Barry, Ernie O’Malley, Peadar O’Donnell and Michael Collins for their parts in the War of Independence. The Civil War grieved me but my sympathies were with the republicans. I respected the men who went to Spain to fight fascism and had no time at all for those who went to support Franco. Nor had I any time for the Blueshirts, as the Irish fascist organisation was called.

Because of my interest in politics I was excited when Jack Murphy, a candidate for the unemployed, was elected to the Dáil (the Irish parliament). This was a cause of great hope for the unemployed and poor of Dublin. But as he was a lone voice in the Dáil, without backing or support or political experience, he seldom got a hearing. Rumours were spread that he was a communist and he became a subject of scorn in the media. As a result he locked himself in a room in a terraced house near Christchurch Cathedral and went on hunger strike to draw attention to the injustice and inequity of the political system. Again, the black propaganda got to work, this time alleging that he was secretly having food delivered to him and that his hunger strike was a sham. Ultimately he came off the hunger strike, resigned his Dáil seat and emigrated with his family to Canada. This brought an end to the Unemployed Workers Movement. It was reckoned on the streets that the Archbishop of Dublin had influenced Jack to give up his struggle and leave the country. It was even said that the church paid the fare to Canada and arranged for employment and accommodation for Jack and his family.

It disturbed me that Ireland was in such a mess of poverty, unemployment, and emigration and that the existing system seemed unable to make things any better. The fact that the country was divided and partly occupied by Britain influenced my thinking strongly. But what could I do about it? Then one evening I saw a man selling the United Irishman paper outside the General Post Office in O’Connell Street. I bought a copy and learned that Sinn Féin still existed. I read the reports of IRA arms raids on British Army barracks in Armagh and Omagh in the North, and found it very interesting and exciting that there was still some resistance to British rule in Ireland. Shortly thereafter I located the George Plant Cumann of Sinn Féin in Crumlin and became a member. I was 16 years old.

The main activities in the branch were attending meetings and selling the monthly publication, the United Irishman. But these activities were too mundane for me. What I really wanted was to make contact with the IRA. Britain still occupied part of my country and the only people I could see who might do something about it were republicans, and that meant the IRA. It seemed logical to me that territorial independence was essential if we were ever to have economic independence. Two IRA prisoners in Belfast, Tom Mitchell and Philip Clarke, were elected MPs in Mid-Ulster and Fermanagh/South Tyrone constituencies in the 1955 elections with a total of over 150,000 votes. This indicated strong support for republicanism.

A year later I joined the IRA. Contrary to popular belief, it was not easy to locate or join. In fact, it was far easier to get out than to get in. For its own survival, the IRA had to check out each new recruit. The fact that my Dad was a Garda, as police officers are called in Ireland, was not an obstacle to my being accepted into the organisation, and neither did it deter me from entering. I knew that I was embarking on a road very different to the one he was travelling, but I felt I was correct and that was sufficient for me. There was a three-month course for recruits. This induction or education course included history, politics, IRA rules and regulations, debate and question and-answer sessions, all aimed at the recruiting officer being able to decide whether to accept or reject a potential volunteer. We were told in no uncertain terms not to expect anything romantic about being in the IRA, that it was not a democratic organisation. It was the Irish Republican Army and required discipline and obedience from its volunteers. It was made clear to us that we might have to face the prospect of imprisonment, injury or even death. If we were not prepared for such possibilities, we were told, we should withdraw and could do so at any time. There was one condition on leaving: no talking to anybody about the organisation afterwards.

I did not tell my family or anyone else that I had joined the IRA. And my already established practice of hill walking at weekends was a perfect cover for weekends spent training in the mountains. This involved learning the use of explosives, firearms training and field craft. I already knew how to read maps, use a compass and live in the hills, which was an advantage. There were also meetings during the week called parades, where we were instructed in the use of small arms, tactics and theory.

The IRA was working towards starting an armed campaign against the British occupation of the six counties in the North. The aim of the campaign was basically to break down the British-controlled administration in the occupied territory and force the withdrawal of Crown forces. It had been successful in training men to a high standard, but was unable to hold such trained volunteers in check when they wanted action. As a result, there was a split in the Dublin leadership led by Joe Christle, a charismatic and vocal advocate of immediate action. Joe and his followers believed, and not without some credibility, that the leadership of the IRA, being older men, were reluctant to take on British forces in Ireland. The raid on Roslea RUC barracks by Saor Uladh (Free Ulster), a small group led by Liam Kelly, during which Connie Green, a leading member, was killed, also put the IRA leadership under pressure to commence action in the North.