1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The War Vault

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

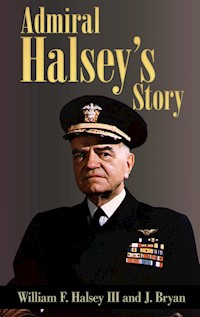

Fleet Admiral "Bull" Halsey was an important allied naval leader in World War 2. His autobiography Admiral Halsey's Story surveys the key events of the war in which he was an active participant, from the immediate aftermath of Pearl Harbor to battles in the South Pacific, and to the final year of the war during which he commanded the U.S. Third Fleet

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Admiral Halsey's Story

William F. Halsey III and J. Bryan

Published by The War Vault, 2019.

Copyright

Admiral Halsey’s Story by William F. Halsey III and J. Bryan.

Published 2019 by The War Vault.

First E-book edition: 2019.

ISBN: 978-0-359-87692-1.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Further Reading: Billy Mitchell: Founder of Our Air Force and Prophet Without Honor

1

––––––––

MY LIFE REACHED ITS climax on August 29, 1945. I can fix even the minute, 9:25 A.M., because my log for the forenoon watch that day contains this entry:

“Steaming into Tokyo Bay, COMTHIRDFLEET in Missouri. Anchored at 0925 in berth F71.”

For forty-five years, my career in the United States Navy had been building toward that moment. Now those years were fulfilled and justified.

Still, I don’t want to be remembered as “Bull” Halsey, who was going to ride the White Horse. “Bull” is a tag the newspapers tied to me. I was named for my father, so I started out as Young Bill; then I became plain Bill; and more recently I suppose it is inevitable for my juniors to think of me, a fleet admiral and five times a grandfather, as Old Bill. Now that I am sitting down to my autobiography, it is Bill Halsey whom I want to get on paper, not the fake, flamboyant “Bull.”

Correction: This will not be an autobiography, but a report. Reports are the only things I know how to write since half my time in the Navy has gone to preparing them. Although I intend for this once [one time] to throw in as many stories as I like, rattle some skeletons, and offer some apologies and second guesses—amusements which official reports discourage—I don’t intend to discard the official form completely. This report will be as clear and true as I can make it; it will contain all the pertinent facts I can remember, whether they are to my credit or not; it will avoid fields like philosophy and politics, where I am easily lost; and it will be consecutive, beginning with my ancestors and ending with my retirement from active duty.

When I filter the old Halseys whose records or traditions survive, I find that most of them were seafarers and adventurers, big, violent men, impatient of the law, and prone to strong drink and strong language. The most famous sailorman among us was Capt. John Halsey, whom the Governor of Massachusetts commissioned as a privateer in 1704. Captain John’s interpretation of his commission is implicit in the title of a book which describes his exploits, A History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pirates. I enjoy reading how his little brigantine once took on four ships together and captured two of them, with $250,000 in booty; but the most moving passage tells how he died of a fever on Madagascar in 1716 and how he was buried there. Part of it is worth quoting:

The prayers of the Church of England were read over him, colors were flying, and his sword and pistol laid on his coffin, which was covered with a ship’s jack; as many minute guns fired as he was years old, viz.: 46, and three English volley and one French volley of small arms. He was brave in his person, courteous to all his prisoners, lived beloved and died regretted by his own people. His grave was made in a garden of watermelons and fenced in with palisades to prevent his being rooted up by wild hogs, of which there are plenty in those parts.

The seafaring strain in the Halseys now ran underground for a century, then emerged for good. In 1815, Capt. Eliphalet Halsey, sailing out of Sag Harbor, took the first Long Island whaler around the Horn. In the next forty or fifty years, a dozen other Halsey whaling masters sailed in his course. Following them, my father went into the Navy; I followed him, and my son followed me.

My father entered the Naval Academy in 1869, with the class of 1873. He pitched on the baseball team — underhand, in those days — and had the reputation of being nimble with his fists. One of his classmates told me that just before they graduated, he and my father “Frenched out” (went into town without permission) and were spotted by a master-at-arms as they were returning. Both were up to the limit in demerits and knew they would be dismissed if they were reported. So, my father took a big chance; he rushed the “jimmy legs” and knocked him out before he could recognize them.

Father and Mother were married in 1880. She was Anne Masters Brewster, one of fourteen children of James Drew Brewster, of New York City, and Deborah Grant Smith, of Philadelphia. I was born in my grandfather Brewster’s house in Elizabeth, New Jersey, at 134 West Jersey Street, on October 30, 1882, and there I spent my early childhood. (The house is now a tearoom, “Polly’s Elizabeth Inn.”)

Dad had been ordered to sea shortly after his marriage, and when he finally returned ashore, to duty at the Hydrographic Office in New York, I was two and a half years old. His first sight of me must have given him a shock. To my joy, and to Mother’s anguish, he hustled me down to a barber and had my long yellow curls chopped off. He was shrewd enough to preserve them, though, and whenever I misbehaved, he could always bring me to heel with a threat to paste them on again.

My young sister Deborah and I had the usual childhoods of “Navy juniors.” We lived in six cities before I reached my teens. In the fall of 1895, I went to Swarthmore Grammar School, near Philadelphia. At the end of my second year there — the first time I had spent two consecutive years at the same school — Dad returned to the Naval Academy, as an instructor in physics and chemistry.

I had always intended going into the Navy and I was now approaching fifteen, the lowest age for a naval cadet, so we began looking about for an appointment. We wrote to every politician we knew and to many we didn’t knew. I had already written even to President McKinley.

I received no answer, but we were so confident of an eventual appointment that Dad entered me at Professor Wilmer’s prep school for the Academy. A year passed, and still the appointment didn’t come through. When the second year failed us, I decided that if I couldn’t get into the Navy as a cadet, I could as a doctor, and Dad agreed to let me study medicine at the University of Virginia.

I picked Virginia because my closest friend, Karl Osterhaus, was going there. I didn’t learn much, but I joined Delta Psi — I still wear its emblem on my watch chain — and I had a wonderful time. My natural disinclination to study was abetted by my growing passion for football. I wasn’t good enough to make the varsity, but I was occasionally allowed to play on the scrubs, at left end. In our last practice before the important Georgetown game, a play came toward me, and when it was untangled, the star quarterback had a broken leg. I was in the same fix as many a military man in many a campaign—they didn’t know whether to give me a Medal of Honor or a court-martial. The student body would have been happy to hang me, but the coach took me to Washington with the team. Most stories like this end with the despised scrub redeeming himself by the winning touchdown. My story is an exception. I didn’t even get into the game.

The following spring, Congress authorized five additional appointments to the Academy, and Mother camped in McKinley’s office until he promised her one for me. I had to cram like the devil to pass the entrance examinations, but I managed it and was sworn in on July 7, 1900.

The class of 1904 has several distinctions: we were the last to enter the Academy with less than 100 men, the last to be designated “naval cadets” instead of “midshipmen,” and the last that never lived in Bancroft Hall, the present dormitory. On the other hand, we were the first whose senior cadet officer was a five-striper. My first year at the Academy — my plebe, or fourth-class year — the cadet body totaled only 238, or enough for a battalion, which was commanded by a four-striper; but by my first-class year we totaled more than 600, enough for a regiment, and the cadet commander sprouted another stripe. I was not he. I never had more than the two stripes that went with my duties as adjutant of the second battalion.

The Annapolis-West Point system of marks is unique, as far as I know: 4.0 is perfect, and 2.5 is barely passing. If you average 3.4 or better, you are entitled to wear a star behind the anchor on your collar. Although I broke into the top half of the class my final year, my average was usually closer to “bilging” than to a star. In fact, at the end of my first month of theoretical mechanics, I had a 2.28, and Dad strongly advised my dropping football. When I told him I had rather bilge, he was furious. Fortunately for me, a good many other men were rated unsatisfactory in the same subject, so we arranged for the bright members of the class to tutor us for the next examination and to dope out the questions for us.

When the exam was over, I went to Dad’s quarters for lunch. He met me at the door and asked if the marks had been posted.

“Yes, sir.”

“What did you make?”

“I got 3.98, sir.”

Dad stared at me for a full minute. “Sir,” he finally asked, “have you been drinking?”

My football was confined to the scrubs, the “Hustlers,” for the first two years, but just before the opening game of the 1902 season, the regular fullback was badly injured, and I was put in. I kept the job that season and the next, my last. Here is as good a place as any to state that those two teams were probably the poorest that the Academy ever produced, but poor as they were, they were no poorer than their fullback. More than forty years later, General of the Army Eisenhower, whom I had never met before, came up to me in Fleet Admiral King’s office in Washington. His first remark was not, “I’m glad to meet you,” or, “How are you?” but, “Admiral, they tell me you claim to be the worst fullback that ever went to the Naval Academy.”

I wasn’t sure what this was leading to, so my answer was a bit truculent. “Yes. That’s true. What about it?”

Eisenhower laughed and stuck out his hand. “I want you to meet the worst fullback that ever went to the Military Academy!”

Army beat us 22 to 8 in 102 and 40 to 5 in 1903, the stiffest beating in our rivalry. As one of the two men who played the entire game, I was thoroughly beaten myself. Each of those aches and bruises came back to me one day in 1943, when I was Commander of the South Pacific, and Maj. Gen. Charles F. Thompson flew over from Fiji for a conference. I told him, “General, the last time I saw you, you were rubbing my nose all over Franklin Field.” “Big Charlie grinned. “How did I know you were going to become COMSOPAC?”

So much for the bitterness supposed to grow from inter-Academy sports!

Next to studies and football, my strongest recollections from my Academy days are of parades and summer cruises. Parades were our bane, but hardly a moment of our three cruises was less than a delight. This opinion was held, of course, by the poor wretches who had a tendency toward seasickness. I am lucky, I have never been seasick in my life. (Many of my shipmates on the old Kansas were made even queasier, during a North Atlantic gale, by watching me guzzle a large Camembert cheese.) I have been slightly deaf since youth, but if I had to choose between deafness and a delicate stomach, I would keep the status quo.

Our transition from salty-talking landlubbers to real sailormen began on these cruises. Half of each we spent on a steamship, such as the old battleship Indiana, and half on a windjammer, usually the Chesapeake, a steel square-rigger. I was a royal yardman on my third-class cruise on the Chesapeake. Two years later, I had worked up to port captain of the maintop, the second most responsible job in our class. I was doubly pleased with my promotion; Dad had been navigator of the cruiser Newark during the Spanish-American War and was now not only head of the Department of Seamanship but captain of the Chesapeake, and I wanted to show him that I might become the fine all-around sailorman that he was. The folly of my ambition was impressed on me when the Academy’s chief master-at-arms told me at graduation, “I wish you all the luck in the world, Mr. Halsey, but,” he shook his head sadly, “you’ll never be as good as a naval officer as your father!”

When we were on the Indiana our third-class year, several of us decided to get tattooed, as a certificate of sea-dogginess. Some artist among us drew the sign — a foul anchor in blue, with its chain forming an “04,” and a red “USNA” on the crown — and a coal passer who was in the brig for drunkenness engraved it on our shoulders. It was hard to tell which was filthier, he or his instruments, and Lord knows why we all didn’t die of blood poisoning. However, the risk passed, but the tattoo remains, to my frequent embarrassment. Dad had been tattooed four times and had advised me against such foolishness, but as usual I was too headstrong to listen.

The Navy underwent a great expansion during Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency. In order to furnish officers for the new ships, the Academy course was slightly shortened, and the class of 1904 was graduated on February 2 instead of in June. Sixty-two survived from the original ninety-three. My final standing was only forty-third, but that didn’t matter; what mattered was that I was now Passed Midshipman Halsey.

All this was long ago. Nearly two-thirds of my classmates are dead, and not one of us is left on active duty. But there might be one if a close friend of mine received his justice. I refer, and will refer again, to Husband E. Kimmel.

New graduates of the Naval Academy were usually granted one month’s leave. I wasn’t. I had requested duty on the battleship Missouri, and when my orders came through, I found that I had only five days before she sailed for Guantánamo, for winter training. It is a curious coincidence that my seagoing career began on one Missouri, the “Mizzy,” and ended on another, the “Mighty Mo.” Although each, at the time, was the most modern battleship in the Navy, the forty years between them brought some interesting changes.

From Guantánamo we moved up to Pensacola for the fleet’s annual target practice. I was watching it from our bridge one morning when I heard a heavy blast and saw a geyser of flame spout 400 feet from top hatch of our after 12-inch turret. Almost immediately there was a second, sharper blast. Four 90-pound bags of powder had caught fire in the turret, and sparks had spattered down into the handling room, igniting a dozen more bags. Twenty-six enlisted men and five officers were roasted alive.

The date of the disaster, April 13, 1904, still looms monstrous in my memory. Indeed, it has cast a shadow over the rest of my life. I dread the thirteenth of every month, and if it falls on Friday, my apprehension almost paralyzes me.

That autumn I was detached from the Missouri for temporary duty at the Academy as assistant backfield coach under Paul Dashiell, who had been given the job in the hope that he would pull our teams out of the slough where professional coaches had left them. Although Army beat us 11 to 0 that year, we tied them in 1905, when I was assigned to the same duty; and in 1906 we licked them, for the first time in seven years.

Shortly after the 1905 season, I left the Missouri for good, with orders to the Don Juan de Austria, a former Spanish gunboat which had been salvaged from the bottom of Manila Bay and was now about to be commissioned. Someone said that she had been designed as a yacht for the Dowager Queen of Spain, when Alfonso XIII was in the offing; certainly our quarters, which occupied the after third of the ship, were as luxurious as a liner’s.

We took the Don Juan to the Caribbean and began a tour of duty that was stupefying in its monotony. Our job was helping to police Santo Domingo and backing up the customs collectors in a couple of ports. Our only amusement was the comic-opera revolutions, and our only excitement the weekly mail steamer from the States.

No, I had one other excitement. On February 2, 1906, exactly two years after my graduation, I received my first commission in the Navy, that of ensign. A passed midshipman was not a commissioned officer but an appointed officer, and an appointed officer received no retirement benefits for a disability incurred in the line of duty. Now I had not only this protection, but a substantial increase in my base pay, and a refulgent gold stripe on my cuff. Lord, how proud I was of that stripe! When I became a five-star fleet admiral, my broad stripe and four single ones cost more than the rest of the uniform. Our three Admirals of the Navy, Farragut, Porter, and Dewey must have had independent incomes to dress up to the demands of their rank.

In March 1907, I reported aboard our newest battleship, the Kansas, which was being rushed to completion for President Roosevelt’s Round-the-World cruise. Sailormen believe that a ship should have a bottle of the best vintage champagne broken across her prow when she slides down the ways; there is an old superstition that christening one with water is as unlucky as drinking a toast in water. We knew that Kansas was a dry state, but we were enraged to discover that our ship had been christened with a bottle of Château Kansas River. When the official party visited us to present a silver service, we retaliated by offering them only lemonade.

Roosevelt’s big-Navy policy made it hard to find crews for all the new ships. However, we filled our complement eventually, and late in the fall we sailed from Hampton Roads — sixteen battleships and five destroyers, under Rear Adm. Robley D. Evans, Commander in Chief of the Atlantic Fleet.

We spent Christmas in Port of Spain, Trinidad, then ran down to Rio de Janeiro and on to Punta Arenas, Chile; continued through the Straits of Magellan and stood north toward Valparaiso; then on to Callao, Magdalena Bay, and San Diego. Here we paraded, and Ensign Halsey, strutting at the head of his company, saw an urchin point at him and heard a yell, “Hey, pipe the guy with a face like a bulldog!”

Something happened in San Francisco that I would have given a month’s pay to see. The Kansas’ skipper, Capt. Charles E. Vreeland, had gone east on a short leave. The train that brought him back also brought half a dozen passed midshipmen, freshly graduated and coming out to join the fleet. Captain Vreeland was in mufti, so they sized him up as a credulous civilian and proceeded on that basis. They described the hazards of Navy life, the importance of their duties, the high esteem in which Admiral Evans held them. They loaded their conversion with Navy jargon, much of it spurious. And with winks and nudges, they explained the function of the “mail buoy,” the “water-cooled sextant,” and other imaginary devices.

Captain Vreeland listened to it all, outwardly grave, inwardly rejoicing. When the train reached San Francisco, he thanked them for their company and expressed the hope that he would have the pleasure soon again. He had it in less than an hour, at the fleet landing. The youngsters couldn’t imagine what business would bring a civilian there and were even more surprised when he asked if he could be of service.

They laughed, “Not unless you can take us out to our ships.”

“Delighted,” the “civilian” said, “My gig here is at your disposal.”

It must have been a glum ride for the young devils, particularly for the one who was reporting aboard the Kansas...

San Francisco was a strenuous round of parties and parades. So were Honolulu, Auckland, and Sydney. We needed the stretches at sea to rest from the hospitality ashore. Melbourne was as gay as the others, but I remember it chiefly because of an incident when I was officer of the deck. Our liberty boat came alongside, and as the party swarmed aboard, I noticed a package left on the floorboards and called down to the last man, “Lad, bring that package up with you!”

His reply took me full aback; a breezy “Right you are, sir!”

He seemed sober, so when he made the deck, I questioned him and found that he was an Australian whom a bluejacket had persuaded to swap clothes and countries. We took the uniform away and turned him over to the police, but we never caught his accomplice. In fact, the fleet left a large number of stragglers in Melbourne. I have heard that some of them became prominent citizens.

Our course from Melbourne to Manila lay through Lombok Strait and the Straits of Makassar, then through the Celebes Sea into the Sulu Sea. By now the fleet had attained such efficiency that a cherished wish of mine was fulfilled: between the time I relieved the watch one morning and the time I was relieved, four hours later, I kept the Kansas in perfect station without once speeding up or slowing down — the only time in my naval career that I have been able to do so.

From Manila we stood up to Yokohama. Despite the entertainments and the tuneless singing of “The Star-Spangled Banner” and the shouts of Banzai! (May you live ten thousand years!), I felt that the Japs meant none of their welcome, that they actually disliked us. Nor was I any more convinced of their sincerity when they presented us with medals confirming the “goodwill” existing between the two governments. I don’t know what became of my medal, but a number of cruise mates sent me theirs after Pearl Harbor, with a request that I return them to Japan at my earliest opportunity. When I took Task Force 16 toward Tokyo in April 1942, I deputized Jimmy Doolittle to complete delivery for me. He did it with a bang.

Of the many parties we attended in both Yokohama and Tokyo, one stands out with special vividness — a party on the battleship Mikasa, the flagship of Adm. Count Heihachiro Togo, who had commanded the Japanese fleet at the Battle of Tsushima Straits, where the Russian fleet was almost annihilated. Before war had been declared, Togo had made a treacherous torpedo attack on the Russians in Port Arthur; and before that, in 1894, as captain of the cruiser Nariwa, he had sunk without warning the Chinese troopship Kowshing thus precipitating war with China. Yet when this national characteristic of deceit was redisplayed at Pearl Harbor, some Americans were naïve enough to be shocked!

My dignitaries were present on the Mikasa, including our ambassador, Thomas J. O’Brien. When the party reached its climax, our hosts insisted on paying their highest compliment to Mr. O’Brien and Rear Adm. Charles S. Sperry, who had relieved “Fighting Bob” Evans. We were alarmed when the Japs laid hands on them, as both men were tall, thin, and delicate, but all they got was three gentle tosses accompanied by banzais. Naturally, we had to return the compliment to Admiral Togo. We were big, and he was a shrimp, so instead of tossing him gently, we gave him three real heaves. If we had known what the future held, we wouldn’t have caught him after the third one.

The next time I stepped on board the Mikasa, history had made some radical changes: she was no longer afloat, but was reverently preserved in concrete at the Yokosuka Naval Base, near Tokyo; and I, I was the commander of a conquering fleet. Although thirty-seven years had passed, I easily identified the spot where we missed our chance that evening.

Christmas, 1908, found us steaming up the Red Sea, toward liberty in Cairo. All hands had dreamed about it and all had been promised it: half to go from Suez, at the Red Sea end of the canal, and the other half, including me, from Port Said, at the Mediterranean end. The first half came back with such wonderful tales that we squared away to make the transit in record time. Alas, just as we started through, we received word that an earthquake had razed Messina, and that we were to rush there at best possible speed. Cairo is still on my rubberneck list.

We could do little for Messina beyond leaving it the Connecticut, with all the fleet’s medical personnel. The rest of our ships scattered to various French and North African ports and reassembled at Gibraltar, where we found a number of British warships and a few Russians, some of which were survivors of Tsushima. Each British ship took an American and a Russian under her wing. Our sponsor, the cruiser Devonshire, we shared with the battleship Sevastopol. At the Devonshire’s opening dinner, the chief engineer of the Sevastopol was seated between our chief, Lt. Edward C. Kalbfus, and his assistant, a Lieutenant Vincent. “Dutch” Kalbfus fancied himself a linguist, and wishing to bring the silent Vincent into the conversation, pointed toward him and explained to the Russian, “Mon premier assistant.”

Vincent bowed and made his only remark of the meal, “Oui, Monsieur. What’s more, je suis le plus belle premier assistant dans le whole goddam United States Navy!”

Gibraltar to Hampton Roads was the last leg of the cruise. We ploughed through a North Atlantic gale and arrived home on Washington’s Birthday, 1909, to pass in review before President Roosevelt on the Mayflower. I have another reason for remembering this review: the Kansas’ newest sister ship, the New Hampshire, took part, painted gray instead of the usual white. I recall how startled I was by her low visibility and how I speculated on its advantages in a battleship duel. I should have saved my wits. Now that radar has been invented, it makes little difference if a ship is painted like a circus poster.

The Round-the-World Cruise, in my opinion — the opinion of a young and inexperienced officer — was a success by every standard. Navally, it brought the fleet to the peak of perfection. Nationally, it increased the prestige of the United States in every country where we showed our flag. And diplomatically, it is not inconceivable that our appearance in Japanese waters at this time prevented a war, or at least postponed it. Japan was fuming over our intervention between her and Russia and was looking for an excuse for trouble. The cruise was one of President Roosevelt’s “big sticks.” He brandished it in Yokohama and Tokyo, and the Japs piped down.

––––––––

Fleet Admiral William Frederick Halsey Jr.

2

THE FLEET SPLIT UP after the Round-the-World Cruise, and I was ordered to Washington to be examined for promotion. The subjects included marine and electrical engineering, international law, ordnance and gunnery, navigation and seamanship, communications, Navy regulations, and courts and boards. I was not much of a scholar, and the cruise had given me little chance to study. My knees still shake when I think of the ordeal of those exams — six days of questions and answers, eight hours a day! Seven of us ensigns took them, and I was one of four who passed. Normally we would have spent the next two years or more as lieutenants junior grade. Actually, we spent about two minutes. There were vacancies in the grade of senior lieutenant, so we were sworn in as j.g.’s, then promoted immediately afterward.

My new orders sent me to the Charleston Navy Yard, to take command of a torpedo boat, one of a motley assemblage of old buckets that had been laid up for years. Still, no subsequent command is ever as important or as thrilling as your first, and I was a proud man when we hoisted the colors and the commissioning pennant on the Dupont. Right there I began a career in torpedo boats and destroyers that lasted for twenty-three years. From this date until June 1932, except for one year as executive officer of the Wyoming, I spent all my sea duty in destroyers.

That fall, after maneuvers with the fleet off Provincetown, we steamed down to Jacksonville, where I was detached and granted a month’s leave. I was going to get married. Three years before, the Don Juan had stopped at the Norfolk Navy Yard for some of the repairs she was continually requiring, and I was drilling a squad on her well deck one afternoon when something hit my cap and knocked it off. It was a muff, obviously thrown by a pretty girl standing nearby with the wife of our exec.

I learned later that the girl had asked, “Who’s that young officer over there — the one who takes himself so seriously?”

The exec’s wife told her. Then came the muff.

I dismissed the men, who were laughing, and recovered the muff. The girl tried to get it back, but I refused until she told me her name. She was Frances Cooke Grandy, from Norfolk, a first cousin of Wiley Grandy, Charlie Hunter, and Armistead Dobie, all of whom had been close friends of mine at the University of Virginia. Despite the boys’ sponsorship, the elder members of Fan’s family were something less than enthusiastic toward the aspirations of a Yankee Navy officer. One of Fan’s uncles had been chief engineer of the Merrimac in her historic battle with the Monitor, which had taken place almost within sight of the Grandy house, and I found myself branded with partial responsibility not only for the Merrimac’s defeat, but for Gettysburg, the burning of Richmond, and the surrender at Appomattox as well. However, I persevered. Whenever I was given leave, I spent as much of it with Fan as her family would allow; I bombarded her with souvenirs and ardent letters from every port on the World Cruise; and when we returned, my double jump in promotion and pay gave me courage to propose. She accepted me, and our wedding was set for December 1, 1909.

While I was packing my gear at Jacksonville, Lt. Harold R. Stark came in and inquired precisely how and when I was going to the railroad station. His abnormal solicitude should have aroused my suspicions, but it didn’t. Flooded with rapture and benevolence as I was, I assumed that something of my mood had infused my friends too. I foolishly gave “Betty” the information, and he saw to it that I was escorted the whole way by a brass band blaring “The Wedding March.”

Fan and I were married in old Christ Church, at Norfolk. My best man was Dave Bagley, and my ushers were Tommy Hart, Husband Kimmel, and Karl Ohnesorg, all of the Navy. A few days before, my scabbard had tripped on the step of a Jacob’s ladder and upended, and my sword had been given the deep six, so Fan had to cut the cake with a borrowed sword. Ever afterward, when I was required to board or leave a ship, I passed the upper sling of the belt between the grip and the guard, so that the sword could not fall out.

In April 1910, after three months as exec of the destroyer Lamson, I was ordered to the Franklin, the receiving ship at the Norfolk Navy Yard, for duty in charge of the training camp. Now I became the prey of a specter that haunts most naval officers at least once in their careers; I contemplated retiring to civilian life. Fan had told me some news that cast a dazzling light over the prospect of years, not hours, with my family; of swift advancement in a business of my own choice; of an office that would be dry and steady; and of a permanent home. (Everyone has noticed how many old sailormen christen their houses “Dunroamin,” “Snug Harbor,” and the like.) I was interested in marine engineering and in personnel work, and believing that I could handle a job in either field or possibly both, I applied to a friend who had considerable weight in two large engineering firms. His advice was, “Stick to the Navy!” I stuck, but on many a sleepless night during the Guadalcanal campaign, nights when men were dying because my orders kept them there, I wondered whether the advice had been sound or whether I had been a fool to follow it...

My quarters in Norfolk were a comfortable house on the Berkley side of the river, and here our daughter was born, on the tenth day of the tenth month of 1910; she didn’t make her appearance at 10 o’clock, however, but around dawn. The band had the word by 8, when morning muster was held; they started the parade with “I Love My Wife, But Oh, You Kid!” We named her “Margaret” for two of her mother’s relations, and “Bradford” for Brad Barnette, my roommate at the Academy.

My shore duty ended in August 1912, when I was ordered to command the destroyer Flusser. I had hardly settled myself aboard when, to my chagrin, the division was placed in reserve at Charleston, owing to the shortage of personnel. We stayed there all winter, but early the next summer I received permission to bring two ships to Newport to exercise with the fleet, which was simulating war conditions by attacking various Army posts. The young destroyer skippers played for keeps. One of them secured to the Army dock at Fishers Island, led a landing force ashore, and arrested the commander of the Army garrison.

Presently I was directed to take the Flusser to Campobello Island, Canada, and report to the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, who wished to survey the naval installations in Frenchman Bay, Maine. Now began a friendship that endured until Mr. Roosevelt’s death. Unlike most Assistant Secretaries of the Navy (and Secretaries, for that matter), he was almost a professional sailorman. I did not know this then. All I had been told was that he had had some experience in small boats, so when he asked me to transit the strait between Campobello and the mainland, and offered to pilot us himself, I gave him the conn (steering control) but stood close by. The fact that a white-flanneled yachtsman can sail a catboat out to a buoy and back is no guarantee that he can handle a high-speed destroyer in narrow waters. A destroyer’s bow may point directly down the channel, yet she is not necessarily on a safe course. She pivots around a point near her bridge structure, which means that two-thirds of her length is aft of the pivot, and that her stern will swing in twice the arc of her bow. As Mr. Roosevelt made his first turn, I saw him look aft and check the swing of our stern. My worries were over; he knew his business.

Ships of mine had the privilege of flying his flag twice again. Soon after the armistice in 1918, while I was commanding the destroyer Yarnall, I was ordered to take him from Dover across to Ostend. The coast of Belgium had been heavily mined, and although channels had been swept, they were poorly buoyed. A strong tide was running in our channel, and such a thick fog set in that we had to reduce speed. When we nearly passed on the wrong side of a buoy, I said, “The hell with it!”, dropped my anchor, and sent Mr. Roosevelt the rest of the way in our motor launch. I might have risked him and the Yarnall separately, but not together.

The last time I had him on board was in San Francisco harbor, during the Democratic convention of 1920. A few days later I met him on Powell Street. “Bill,” he said, “I’ve just had a fight.”

He was a powerful man then, so it was natural for me to ask, “What hospital is he in, Mr. Secretary?”

He was referring to his scuffle for the Tammany banner, when its delegation refused to join the demonstration for President Wilson. It was at this convention, of course, that Mr. Roosevelt was nominated for Vice President.

In August 1913, I took command of the Jarvis, a brand-new oil-burning destroyer. Those who have never served on a coal burner can’t realize the bliss of an oil burner; with the exception of my one year on the Wyoming, I never again had to go through the nuisance and filth of coaling. We had target practice off the Virginia Capes during the fall, and in January we sailed for Guantánamo and the regular winter maneuvers — war games, ship’s drills, and target practice with guns, torpedoes, and small arms.

The Commander of the Atlantic Destroyer Flotilla was Capt. William S. Sims [William Sowden Sims] who, as a young lieutenant, had made such a cogent case against the fleet’s poor gunnery that President Theodore Roosevelt appointed him inspector of target practice. Sims did an excellent job, and Roosevelt shoved him along, to the extent that he was only a commander when he was made skipper of the battleship Minnesota — the first and only time a commander has been permanent captain of a battleship in the Battle Fleet. This did not increase his popularity with his seniors, although his juniors loved him. I doubt if he was aware of either opinion; he cared no more for popularity than he cared for convention. He seemed to exult in affronting authority. When he was our naval attaché in Paris during the Spanish-American War, he sent back an expense account in which some bureaucrat disallowed a number of petty items, such as cab fares, on the ground that they were not accompanied by signed receipts. Sims replied that he could obtain an abundance of signatures in exchange for a loaf of bread, and if his country had reached a stage where evidence of that sort was preferred to the word of a naval officer, he would resign his commission.

In 1910, he made a speech in London in which he stated, “Speaking for myself, I believe that if the time ever comes when the British Empire is menaced by an external enemy, you may count upon every man, every drop of blood, every ship, and every dollar of your kindred across the seas.”

The severe reprimand that President Taft sent him for his tactlessness, Sims framed and hung in his cabin. And when Secretary Daniels offered him a Distinguished Service Medal for his work in World War I, he refused to accept it; he said that it had been cheapened by indiscriminate award.

I remember him as tall and vigorous, a crisp, decisive talker, and a great believer in conferences. In Guantánamo, he liked to hold them at the officers’ club, and frequently attended in tennis clothes. If he became bored or if the discussion got out of hand, he would break it up by heaving a tennis ball at the speaker.

From Guantánamo we proceeded to Pensacola. Conditions in Mexico had an ugly look, so we arranged that when the ships in the harbor blew a certain number of blasts, all personnel ashore would return aboard at once. The whistles blew on the morning of April 9 — the Tampico incident had occurred — and the entire flotilla put to sea at best possible speed. On the way down we were told to prepare landing forces. This was an unusual assignment for destroyers; we didn’t have the khaki uniforms which a landing force requires, and all we could do was approximate the color, by boiling our whites in coffee. My whole ship smelled like a Greasy Spoon.

American refugees poured out from Tampico in two American yachts, one flying the German naval flag and the other the British ensign, since both these countries were neutral. It was humiliating for us to lie outside a foreign port and see our nationals protected by other flags, but we had strict orders not to provoke further incidents. The refugees were put on board the Dixie, which departed for Galveston, and right there trouble began. It began for the refugees, because there was no extradition treaty between Mexico and the United States; when they arrived in Galveston, a platoon of sheriffs was waiting on the dock. It began for the Dixie, because the refugees refused to leave her, and she couldn’t return to Tampico with them aboard. And it began for us because the Dixie was our only tender; we ran out of fresh provisions and ice and could get no more until she returned. Ever since that week of canned salmon three times a day, I have never been able to look the stuff in the face.

Eventually the Jarvis was ordered to Veracruz. Bad luck had made me acquainted with a number of boisterous Marine officers on duty there, but plain stupidity was responsible for my accepting their invitation to join them on a horseback ride. I knew nothing about horses, and you may be sure my hosts took no pains to pick me a nice quiet one. I had hardly gotten aboard when he wheeled, hurdled a pile of trash, and started making 40 knots down the highway. There I was in the stern sheets with no steering or engine control, and if someone hadn’t had mercy on me and overhauled us, he might be running yet.

I was still raw from this experience when a worse one befell me. The destroyers were taking turns at the mail run to Galveston. The afternoon before the Jarvis’ turn, a fireman reported aboard. He must have thought we were a tourist liner, because he jumped ship two hours later, returned that night roaring drunk, and when the master-at-arms went to put him under arrest, plunged over the side. Those are shark waters. We combed them with searchlights and small boats, only to discover that he had climbed aboard and hidden himself under the after-torpedo tubes. He was hauled out and locked up, and next morning at mast I gave him a summary court-martial and made him a prisoner at large awaiting trial.

By then we were underway for Galveston. We touched there, picked up our mail, and had barely headed back to Veracruz when the master-at-arms reported that our fireman had jumped ship again, and again had returned drunk and obstreperous. I had him brought before me and told him, “If you want to be treated like a man, act like a man. If you want to be treated like a mad dog, act like one, and by God, I’ll chain you up!”

The man said meekly, “Aye, aye, sir. I’ll behave myself.”

Within an hour he was raising hell again. He was still crazy drunk, so — as much for his own protection as for his shipmates’ — I gave orders for his arms and legs to be chained around a stanchion in the storeroom. Unluckily, his hands were left enough play to reach a file on a shelf nearby; he cut his fetters, and hell broke loose for the third time. I had a bellyful of this brawler by now. I ordered him spread-eagled for the rest of the night, his hands chained to one stanchion and his feet to another.

When we released him after breakfast, sober at last, I learned for the first time that only two stanchions that permitted spread-eagling had a low hatch-coaming between them. I was sorry our drunk had spent such an uncomfortable eight hours, but God knows I wasn’t sorry when we reached Veracruz, and I was able to transfer him to a battleship’s brig, since we had none. This sort of conduct bordered on mutiny, so I preferred charges and requested a trial by general court-martial. (The commanding officer of a ship could not order a general court; the only person then so empowered was the Secretary of the Navy.) My recommendation was approved, and the man was tried and convicted.

I hoped that this would end the incident, but some weeks later I received an official letter from the Navy Department enclosing a letter from the man’s parents, who accused me of cruel and inhuman treatment in chaining their son, and additional inhumanity in endangering him by blundering around the congested waters of the Gulf of Mexico with no lights showing, and at a speed perfectly impossible to attain with my ship! Not only that, but with the letter came a personal note from a friend at court, warning me to reply with the utmost care, as Secretary Daniels had hinted that he was going to make an example of me!

At that moment my naval career was in its most serious jeopardy. Conscience and common sense told me that the steps I had taken were proper, but I doubted my ability to convey this to the Secretary. I sweated over a dozen drafts of my reply, then had it checked and edited by friends. The final version called attention to the inaccuracies in the parents’ letter and pointed out that I had fully explained and acknowledged the restraining measures in my sample charges and specifications — in short, that the Secretary had been in possession of all the facts when he ordered the court.

I sent my letter and held my breath. Mr. Daniels never answered.

The destroyers proceeded north to Norfolk at the end of spring, and I was reunited with my family. At Haiti I had acquired a small, bold, vicious parrot who developed such an inordinate appetite for alcohol, and became so vulgar and irresponsible under its effects, that I was reluctant to take him home. However, my chief engineer enjoyed the company of this depraved bird and induced me to swap him for one of his own, a handsome Brazilian named Pedro. My wife’s welcome to Pedro was cool, but young Margaret adored him. He had only two tricks: he would wail like a spanked child — suggesting to the neighbors that we were brutalizing Margaret — or he would laugh like a madman. Between tricks, he applied his criminal wits to escaping from his cage and perpetrating new deviltries.

I noticed he was unusually quiet one day, and when I investigated, I found him happily scissoring the crown from my only civilian hat. It is hard for me to find a hat to fit my large head; I am ashamed to say that I slapped Pedro across the floor. He had no use for me from then on and tried to nip me whenever I approached. He also hated our Negro maid. I have seen him back her into a corner and nip at her feet until she screamed.

That year, 1914, was the year that Secretary Daniels issued his famous Order 99, directing that all alcoholic beverages be removed from Navy ships before July 1. On the night of June 30, the Jarvis gave a party on her fo’c’sle to mourn the demise of the drinking Navy. It was a melancholy occasion for the officers, but the enlisted men took it in their stride. Although they had never been allowed to have liquor aboard, many of them habitually smuggled it in, and when it ran out, drank even alcohol from the torpedoes. The authorities had tried to make “torpedo juice” unpalatable by adding croton oil and other adulterants, but the thirstier bluejackets simply bought a loaf of stale bread, sliced off its heels, poured in their “torp,” and squeezed out pure alcohol.

I have never been convinced of the wisdom of Order 99. True, it stopped midday drinking and thereby insured a full afternoon’s work; but to a man who has just had a tense, hazardous flight or a cold, wet watch, there is no substitute for a tot of spirits, as the Royal Navy well knows. Soon after Pearl Harbor, I took the law into my own hands. As Commander Aircraft Battle Force, I directed my representative ashore, Rear Adm. Aubrey W. Fitch, to requisition 100 gallons of bourbon for our flight surgeons to issue to our pilots. This eventually became standard practice. I don’t remember if it was ever officially approved, but I do remember that “Jake” Fitch accused me of inaugurating highly unorthodox procedure and leaving him to hold the bag.

However, we had little time for griping about Order 99. World War I broke out in August, and the Jarvis was assigned to patrol off New York Harbor. Part of our job was to keep an eye on the Winchester, a yacht so fast that one of the belligerents was expected to buy her and try to take her abroad, in violation of our neutrality as it was then interpreted. A British patrol — a cruiser or a battleship — also watched the Winchester. Early in the fall, our destroyers began a series of maneuvers which were to end off Sandy Hook Lightship. The weather shut in, and the Jarvis was unable to get a single celestial fix during the whole of a 600-mile run on various courses at various speeds. One morning, with only the vaguest idea of our position, we popped out of the thick weather, and there, dead ahead, was a strange warship. It proved to be the Britisher, but both vessels had a miserable few minutes, each expecting the other trigger-happy crew to open fire.

We popped Back into the weather and into fresh danger. I didn’t see it; I didn’t even know what it was; I simply knew it was there — a hunch too strong to be ignored. I ordered, “Full speed astern!” and when our way was off, I hailed a fisherman close aboard and asked for my position.

He yelled back, “If you keep going for half a mile, you’ll be right in the middle of the Fire Island Life Saving Station!”

What caused me to back my engines was probably a feeling of drag from the shoaling water or the sudden appearance of large swells off the stern. I don’t know, but something told me I had to act and act fast.

In 1915 I was assigned duty at the Naval Academy, in the Discipline Department. Excepting the plebes and a few upperclassmen, the midshipmen were on leave when I reported. The night they returned I had another hunch — I knew that the first man I would have to put on report would be the son of a friend of mine. Sure enough, my routine inspection after supper took me into a room filled with contraband tobacco smoke. I asked, “Who’s in charge of this room?”

A fine-looking lad said, “I am, sir.”

“Your name?”

“Midshipman Macklin, sir.”

“Are you a son of General Macklin?”

“Yes, sir.”

I cried, “My God, I knew it!”

I immediately started a one-man campaign to have the smoking regulation changed. A regulation that can’t be enforced is a poor regulation, and my own experience as a cadet had convinced me this was one of them. The Commandant of Midshipmen warned me that the medical officers would fight, and they did. But the regulation was eventually changed, and I hope that my efforts contributed.

By now I had eleven years’ experience in handling enlisted men, and I saw no reason why midshipmen should not be handled the same way. I would punish trivial offenders with no more than a bawling out — a jacking up — but major offenders would have the book thrown at them. My theory was solid, but it ignored one factor which I should have kept in mind: midshipmen regard discipline as a game, with the duty officer their opponent and an unpunished infraction their goal.