Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

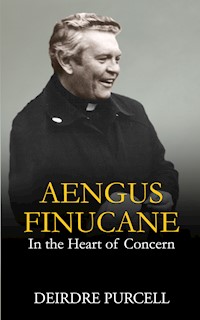

In this powerful new biography, Aengus Finucane: In the Heart of Concern, the result of over 80 interviews and extensive travel, Deirdre Purcell explores the life and work of Concern founder Father Aengus Finucane. She charts the work he did to build Concern into the global charity and vital player in relief efforts around the world that it is today. A charismatic humanitarian visionary, he travelled the world to go to the aid of the poorest of the poor, whilst helping to turn the small charity into an international phenomenon. In many ways the most humane of priests, Aengus sought to address its root causes. The charitable work of Concern, under his leadership and influence, was not limited to responding with aid to emergencies as they arose; it also involved development, creating meaningful, long-lasting and positive change. The legacy of Aengus Fincuane is vast, and Concern, the charity he helped to build, continues his work today, deploying over 3,000 staff and reaching 12 million people in the world's poorest countries. They respond to famines and floods and stay long after the television cameras have left, delivering sustainable improvements to the lives of the poorest. They ensure the work of Aengus Finucane will continue.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 529

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

AENGUS FINUCANE

AENGUS FINUCANE

IN THE HEART OF CONCERN

BY DEIRDRE PURCELL

Aengus Finucane: In the Heart of Concern

First published in 2015

by New Island Books

16 Priory Hall Office Park

Stillorgan

County Dublin

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © Deirdre Purcell, 2015.

The Author acknowledges that this Work has been commissioned by Concern Worldwide, a company limited by guarantee registered in Ireland (company number 39647) which has been granted charitable status (charity number CHY 5745) and has its registered offices at 52/55 Lower Camden Street, Dublin 2, and published by New Island Books, registered in Ireland (Company Number 186067) whose registered office is at 16 Stillorgan Office Park, Stillorgan, Co. Dublin.

PRINT ISBN: 978-1-84840-386-4

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84840-387-1

MOBI ISBN: 978-1-84840-388-8

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing Data.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book is dedicated, with humility, to the founders, fundraisers, donors (whose generosity makes the work possible), staff and volunteers of Concern, who, along with their families and supporters, have fulfilled and continue to fulfil the organisation’s vision, as articulated by Father Aengus Finucane, to lift millions of the poorest of the poor out of destitution, starvation, violence, exploitation, neglect and despair.

CHRONOLOGY OF KEY EVENTS

1932 Birth of Aengus Cornelius Finucane, Limerick.

1936 Sexton Street School, County Limerick.

1944 Novitiate, Kilshane Seminary, County Tipperary.

1959 Ordination as Holy Ghost Father (Spiritan).

1959–1968 Pastoral parish mission work in Nigeria.

1967 Outbreak of civil war in Biafra/Nigeria.

1968–1970 Biafra airlift at ULI airport.

1968 (March) Africa Concern founded by Father Raymond Kennedy, John O’Loughlin Kennedy and Kay Kennedy.

1971 First Concern Volunteers go to Calcutta.

1972 Concern volunteers go to Bangladesh.

1972–1978 Aengus Finucane appointed as director of Bangladesh.

1981 Aengus Finucane becomes CEO of Concern.

1988 Concern office opens in Belfast.

1991 Concern office opens in London.

1994 Concern office opens in New York.

1997 Aengus Finucane retires, becomes honorary president of Concern US.

1999 Concern office opens in Chicago.

2008 Aengus Finucane’s final trip overseas (Haiti).

2009 Aengus dies.

Do as much as you can,as well as you can,for as many as you can, for as long as you can.

– Father Aengus Finucane, C.S.Sp

‘Aengus reflected the best of who we are as a nation, embodying and promoting a spirit of humanity, dignity and equality. His courage, leadership and drive to reach the poorest changed the way we think about and work with those most in need. If I’m asked about his legacy, I would point to the fact that he not only saved but transformed the lives of millions of people across the developing world.’

– Dominic MacSorley, CEO of Concern

INTRODUCTION

‘We have a strong inclination to do evil,

and you have to fight like hell to do any good.’

– Aengus Finucane

How do you define Aengus Finucane? Far from easily.

On the surface the task might seem simple enough because there are so many visible and obvious facets: Spiritan (Holy Ghost) priest, CEO of Concern in Ireland and latterly honorary president of Concern US, native and Freeman of Limerick City, recipient of many awards and honorary doctorates and an influence on governments and on other non-governmental agencies in the area of development and aid. A people person who was the charismatic focus of a huge circle of intensely loyal friends.

Party-giver. Storyteller. Family man in its widest sense. A big-picture guy. But above all, a passionate – and compassionate – friend of the poorest of the poor in any country, or on any continent inflicted with famine, war, natural disaster or any emergency situation that could benefit from his attention and that of the organisation he loved and cherished from the bottom of his huge, brave heart.

As well as his considerable height, he carried the kind of weight and girth that would do credit to the front row of his beloved Munster rugby team, making him seem taller still. ‘A giant’ was a description not infrequently applied to him and he was most definitely an imposing physical presence. Sonorous too. In times gone by, Holy Ghost seminarians were, we’re told, trained to project their sermonising voices by dint of standing at one end of a football field to address a tutor at the other end. In the course of that schooling, Aengus’s voice, naturally a resonant bass, became, according to one informant, ‘even boomier.’

When Father Aengus Cornelius Finucane entered a room, his entrance was noted. When he held court at one of his parties, the focus was on him. When he addressed a gathering, made a case to a Prime Minister or importuned a new Concern donor, his audience paid attention.

His reputation had perhaps preceded him in the case of one potential donor at least, because during their first meeting in a New York restaurant this man reported that he did all the talking deliberately so as not to let Aengus get a word in. Predictably, perhaps, the man subsequently caved, became a staunch, lifelong pal and proponent of his new friend’s organisation and is now chairman of Concern US. He is Tom Moran, whose day job is president and CEO of the highly successful insurance company Mutual of America, and is one of the scores of people interviewed for this book.

Aengus was always a prolific correspondent, report-writer and chronicler of events during his working life. Even before joining Africa Concern, so named on its founding in March 1968, as a Holy Ghost Father serving in his Nigerian parish, he constantly wrote home. Throughout a subsequent lifetime with Concern, alongside this evocative correspondence, he sent an additional flow of memos and reports to headquarters, in which, employing distinctive and flowing penmanship, he would outline achievements and failures, obstacles overcome or ways round them, along with suggestions for future innovations.

His brother, Father Jack Finucane, had followed into the Holy Ghosts, to Nigeria and then into Concern, himself serving there with great distinction until he retired. After his older brother’s passing, he gathered together all these documents, including the personal letters and musings and with the help of family members, spent months categorising and filing them for future reference.

Finally, however, the number of archive boxes proved to be so large he could not house them all, so he gave them into the care of Concern headquarters in Camden Street.

Where, in error, their contents were shredded.

The tragedy is small in comparison to the life-and-death situations both brothers encountered daily in their work in what was then described as the Third World. Although very different in personality, inclinations and habits, sometimes bickering and disagreeing as brothers do, Aengus and Jack had been deeply devoted not just to their cause in service of social justice and to the poorest of the poor but to each other, so for Jack, already devastated by his brother’s passing, the destruction of this archive served further to deepen his grief.

And so, with very few papers having survived the shredder – and many of these quite repetitive – the method chosen to write this book was by interview, recording the voices of people who knew Aengus, loved him, or in some cases, differed strongly with him but respected him just the same. Here are reactions and recollections of huge events, plus personal assessments and anecdotes about this singular cleric from a wide circle of people he loved, worked with and occasionally exasperated, including family, friends, donors and fellow priests.

In this new archive, there are also the voices of outsiders who encountered him and his brother within and outside the fields of Concern, including those of the current and former presidents of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins and Mary Robinson, the latter famously having gone to Somalia at Aengus’s direct invitation during the worst phase of the conflict there.

The most vivid accounts of the organisation, and of the Finucane brothers, comes from Concern volunteers who, as the backbone of early operations, lived and worked closely with one or both of the Finucanes. Many were in their (very) early twenties when they travelled shiny-eyed to places they and their parents had to look up in school atlases; they knew they were bound for strenuous work in areas of poverty-ridden squalor but went anyway.

A word here about the way these recordings have been used – and a caveat. Every one of the interviews is fascinating in its own right: Concern – and Aengus – sure knew how to attract and recruit dedicated and innovative individuals. What has been intriguing is not just each individual’s assessment of Aengus, but the way in which, with a few exceptions, views about his character and ability concurred, even when the holders had clashed with him about certain issues or styles of management.

Equally striking was to hear details about their reasons for joining, the attitude changes and fast-tracked maturity engendered by stints abroad in such taxing environments. They came to Concern as professionals – nurses, administrators, accountants, agronomists – but very quickly flowered to become astonishingly able and independent innovators and advocates, even entrepreneurs.

With their stories, these interviewees, a few of whom are undeniably mavericks, show what a broad church Concern was in Aengus’s time, and still is. Their tales illustrate the power of his influence: he could stimulate a diverse spectrum of characters to play to the highest level of ability.

When talking about Aengus (or Jack, or Concern in general), some of the experiences related by outsiders, for instance broadcaster Mike Murphy and journalists Donal Byrne and Tom McSweeney, are included to show how difficult the circumstances in which these aid workers and their leaders operated really were, even from the time when they got out of their beds every morning.

Aengus achieved what he did through inspired and visionary thinking, leadership and doggedness about reaching goals. He saw the world, not as his oyster as many global businessmen do, but as an imperfect network of nations presiding over regimes of unequal opportunities for multitudes of their citizens, who, due to blatant injustice or poverty, were forced to live out their lives at sub-human level. It was his mission, he believed, to rebalance these inequities inasmuch as he could do so. He led the charge, but knew that he could not win the battles he chose on his own. He did it with carefully selected teams, and strong back-up from his organisation.

One caveat about these interviews as research-resource: details can be misremembered as time passes, and there have been some radically different versions of the same event, necessitating a stab at judging which was the more, or most authentic. (The writer, Tony Farmar, who has written a comprehensive history of Concern’s development during its first thirty years, Believing in Action, came up against the same conundrum.)

At this remove, many of the legends that have grown up around Aengus, still referred to, erroneously, by many as ‘one of the founders of Concern’, are a little hazy. He loved the Irish language (especially Nuacht on TG4), and would understand perfectly if some of these variations on what happened to him might fall under the headline of the traditional Gaelic: Dúirt bean liom go ndúirt bean léi (go ndúirt bean eile gur inis bean di …). (A woman told me that a woman told her (that another woman said that she was told by a woman…)). In other words, we’re talking about multiple and exponential hearsay.

Aengus was a ‘Titan’, said many interviewees, but that description encapsulates only a small part of the story. Although no pushover, it has emerged that he was tender with greenhorn volunteers. When remembering him, volunteers and colleagues said again and again that a major talent of his was the ability to discern latent aptitudes and talent in those who had not yet discovered these in themselves. Known to have a pithy catchphrase for all eventualities, in the context of spotting hidden talent, his ‘Give me the makings’, i.e. give me malleable but previously undetected traits, covered this particular skill.

He exhibited it right from the beginning when faced with youngsters entrusted to his care in the early foreign fields, such as Bangladesh, where he arrived just after the lethal war that sundered East from West Pakistan in the early 1970s. These women and men, middle-aged now, all talked of an action-driven personality, of foresight, goodness and a generous nature. He was ultra-discreet with confidences, apparently being of major assistance when approached for relationship counselling.

A peacemaker and mediator according to most, he could be wrathful and critical when his very high standards, both personal and work-related, were in his opinion breached. These squalls passed quickly,.

People mentioned his bluntness, but also his tact when the need arose. For instance, when he discerned interpersonal spikiness within Concern’s communal living quarters, he would quietly separate the antagonists by moving them around between venues in such a way that those being moved felt they were going somewhere better, and those who remained believed this as well. A few remarked drily that he created inner circles, mostly composed of women, whom he favoured above others. This, it was emphasised, never compromised the work, or their retrospective esteem for him.

While Aengus often received and held confidences from others, he seldom revealed any depth of personal information about himself. Yes, he would chat freely – and long into the night - about his origins and family, about work and work colleagues, about his beloved Limerick, Munster rugby teams, hurling, Gaelic football, history, politics and his days in Bangladesh. He had no problem relating tales about his formative days as a priest-turned-aid worker in Biafra. Yet despite lengthy probing of dozens and dozens of observers, family members, fellow-workers and friends, all of whom wanted to be as helpful as they could, the innermost worries or difficulties of Father Aengus Finucane have remained somewhat opaque. Yet during the transcription of the recordings, sometimes an unexpected little phrase or a small: ‘I wonder if…?’ piece of speculation, or maybe even a sudden, startling insight turned out to be crucial in creating a three dimensional image, the thoughtfulness and depth of this big personality who liked to present himself as convivial and open.

All interviewees were asked individually if they missed him. Many answered immediately and affectionately in the affirmative. Many more took a moment to think about how to answer, and then, almost with wonder, as though the idea had just occurred to them, responded with: ‘But I think he’s still here!’ Indeed, many spoke about him in the present tense.

On the surface, with his appetites for company, get-togethers, late nights and good whiskey, Aengus could glibly be seen as a sybarite. When asked to balance all this praise and love for him with something a little more gritty, the riposte was invariably: ‘He’d never go to bed!’ It is clear, though, that underneath was a profound spirituality. Several of the ex-volunteers have spoken of the serenity they experienced, and he exuded, when he celebrated Mass at the kitchen tables of Concern houses in Bangladesh and other fields – even on the breakfast table in his apartment in the Seabury complex near the seafront in Dublin’s Sandymount. Jack, now retired from Concern, and a redoubtable presence in his own right, was and remains every bit as passionate as his brother about the work of Concern. Like Aengus, in his prime he was highly energetic and born to lead, but is as unalike his sociable and extrovert brother as it is possible to be for those born of the same parents. Definitely not a party animal, he is reserved, seeming almost aloof until you get to know him.

‘Give Jack a problem,’ said one interviewee, and ‘he thinks, comes up with a solution, and sometimes these are ingenious.’ As a team playing for Concern, and as brothers within a family where loyalty was the prime virtue, they were very, very close.

Five years the younger, after ordination as a Holy Ghost Father, Jack too was sent by his superiors to Nigeria, where there were already hundreds of his confrères ministering in the parishes. He was quickly elevated to the rank of Parish Priest of Umuahia not too far from where his brother was situated. They worked hard, and according to one of Aengus’s friends who was also there at the time, like Father Jack in Brian Friel’s Dancing at Lughnasa, this was to be where their working lives would be until retirement or death.

But the state of Biafra then seceded from Nigeria in 1967. Nigeria retaliated by mounting a complete naval blockade, cutting off supplies of food, medicines and all other essentials. As a result, the Biafrans very quickly succumbed to famine and disease.

Along with members of their order and other missionaries, the brothers came together under an umbrella group of aid organisations to participate in a daring and dangerous way of providing supplies: a night-time airlift into an airstrip at a place called Uli from a warehouse on the island of Sao Tome 300 kilometres away. This was funded partially by Africa Concern, founded and run from Dublin by yet another Holy Ghost priest, Raymond Kennedy (at the time at home in Ireland on vacation from his mission post in Nigeria), his brother, John O’Louglin Kennedy, and the latter’s wife, Kay.

This airlift has been well documented, especially via a TV documentary in the Radharc series for RTÉ: ‘Night Flight to Uli’,in which Holy Ghost priest, Father Tony Byrne, who was supervising the airlift from the island, told viewers ironically that on his day of ordination he had not expected to find himself buying planes and running an airline. The aircraft had originally been leased, but because the cost of insurance premiums for such dangerous missions became exorbitant, purchasing became the only option. The Biafra experience, and the parts played in it by both Aengus and Jack, are in themselves worth a chapter of this book and so it is planned.

Until he retired, Aengus was Concern’s public face, although many say that in a lot of ways, towards the end, the organisation outgrew him, not least during a period of enforced absence from the helm because of several bouts of ill-health. Even before he left, Concern had begun to expand and develop rapidly in tandem with its client nations, and to keep pace with the burgeoning expansion of theory and debate in the developmental aid sector along with its affiliate, Concern US, to which our hero rebounded in short order and with renewed ebullience, as honorary president.

This expansion and consolidation continues. Now highly professionalised, Concern works more and more with partner bodies, and although there are volunteers both in the UK and US, these days it depends hardly at all on overseas volunteerism. Unlike its founders and early activists, it does not rely at all on the Holy Ghost Fathers, from whom it grew.

Aengus’s best known ‘action-first’ mantra, and the one that graces his memorial card, is:

Do as much as you can,

as well as you can,

for as many as you can,

for as long as you can.

While Aengus accepted that the core business of Concern was always about the poorest of the poor – and frequently reminded everyone of this – he did begin to worry, said many interviewees, that process and development theory was trumping the needs of individuals and families, particularly women and children. ‘People first, always people’ was his cry. When presented with some new project or report, he would often respond: ‘What’s in it for the poor person?’

Even the tiny minority who criticised what they saw as his principal-teacher management style never lost admiration for his sincerity and ardour for his cause, as well as his effectiveness, both as an administrator in the field and in parting donors from their money.

To be fair, funding had risen during that expansion to multiples of millions. Staff and contract employees entering the organisation were coming in not merely with the necessary qualifications, but with specialist master’s degrees and even PhDs in development aid and related subjects. Donors were demanding more feedback, and even becoming picky with how their money was spent, while large sources of funding from governments, institutional donors, NGO partnerships and charitable foundations brought with them their own demands for process and accountability. In addition, a professional fundraising operation, with professional oversight, alongside the older methods such as the annual Concern Fast, was being promoted with vigour and was proving to be lucrative.

Jack is now around the same age as Aengus was when he died, and the question remains as to how long the Finucanes’ influence will persist. At the time of writing, three chief executives: David Begg, Tom Arnold and Dominic MacSorley, all highly and vocationally motivated, each with an individual modus operandi, have taken office in Camden Street. With the exception of a few now in management, all of the volunteers Aengus knew and loved – and who loved him in return – have gone into other organisations, or have simply retired. Some have taken a seat on Concern’s governing body, the council. All are mortal. When asked to furnish an instinctive answer as to the single most striking quality in Aengus Finucane, David Andrews, the former Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs, did not have to think for long. He knew Aengus quite well, and saw him in action, for instance during the conflict in Somalia when he travelled there with Mary Robinson. He also dealt with the priest at home when Aengus was in full, passionate advocacy as he sought funding for his cause.

Andrews’s response to the ‘striking quality’ question was immediate: ‘Leadership. He was a natural leader. A big man in every sense, yes, a real leader.’

Concern’s ethos, as defined by its founders, was simple: to help the starving children of Biafra. Similarly, when Aengus took over as CEO, the core of Concern’s service was to lift the poorest, most forgotten people out of destitution and into living standards conducive to human dignity. That ethos still holds. And while the two CEOs who immediately succeeded him (Begg and Arnold) may have placed different emphases on ways to fulfil this mandate, both, in interviews for this book, said they had always kept this baseline at the forefront of their minds.

Dominic MacSorley is most definitely his own man with his own vision. Much of that original philosophy survives him as he sits behind Aengus’s big desk, under Aengus’s map of the world, where a handmade, rickety globe of the world presented to Aengus in 1983 by Dominic in a refugee camp on the Thai–Cambodia border is on prominent display.

He is careful, however, not just to look to the past, but also to glean the best of it, marrying its lessons with current thinking.

The word ‘colossus’ was used a lot when journalists, both in Ireland and abroad, eulogised Aengus. Obituaries in newspapers around the world concentrated on his crusade for the poor and downtrodden. This from the Los Angeles Times, for instance: ‘His credo, oft-repeated when stumping for donors, was that other saying of his: “We have a strong inclination to do evil, and you have to fight like hell to do any good.” ’

He lived and breathed Concern, to the extent that some members of his extended family complained that around the dinner table in Limerick, when Aengus was present, there were many abortive attempts to rebel against the continuous, almost boring talk about the organisation. His brother Jack said that in latter years, when the two of them met socially, for instance for a lunch together, they would agree as they sat down that for once there would be no talk about Concern. ‘And within two seconds, we’d be talking about Concern.’

By all accounts, Aengus kept his personal emotions under tight control. Joseph Cahalan, CEO of Concern US, remembers seeing him ‘tear up’ only once. In Chicago, the local fundraising arm of the organisation holds an annual Women of Concern luncheon, established to boost the coffers and to honour a particular woman, but also to raise awareness of the organisation. Cahalan was sitting with Aengus at this event some years ago when he saw a tall, elegant black woman, who was not familiar to him, coming across the room. ‘She was six feet one or two, wearing a white silk suit, and it was clear she was approaching our table.’

The woman introduced herself as a paediatrician, educated as such in Yale, married to a banker. She had heard about this lunch, and that Father Aengus was going to be attending. She said she knew then that she had to attend too because she had last met him when she was an 11-year-old refugee. She lived and worked as she did now, she said: ‘All as a result of Concern.’ It was at that point, added Cahalan, ‘Aengus began to cry.’

Multiplied by many millions, that woman’s survival – and her flourishing – represents Aengus’s legacy, a legacy copper-fastened by another individual case, seen and heard by Dolores Connolly, one of the Chicago Women of Concern.

A number of years ago she accepted an invitation to join a panel discussion about the UN’s eight Millennium Development Goals, two of which aim to halve extreme poverty rates and provide universal primary education by 2015. This panel discussion was to be held in front of an audience of future business leaders, MBA students at the prestigious Notre Dame University in Indiana.

Dolores accepted the invitation:

I mention Concern, and I’m interrupted. At the back of the room, this huge guy gets up. ‘Can you say again what organisation? Are you talking about Concern from Biafra? Are you talking about those two brothers? I’ve heard stories about these two guys. They were trying to starve us out, and these guys would light fires in the night and they would airdrop this food and my father and my grandfather would have to go out and get it off the runway. These guys were legendary in my village! And there were two of them ...’.

He wouldn’t stop talking. He took over the whole meeting.…

Job done for Concern. Aengus’s legacy confirmed.

– Deirdre Purcell, Mornington, 2014.

1

‘Stand up and let your brother sit down!’

– Delia Byrnes Finucane (Aengus’s mother)

Aengus’s sibling, Sister Patsy Finucane of the Mercy Congregation, speaks about her brother’s obsession with his life’s work:

Really and truly, you’d have a pain in our house – every meal, every function. I used to get irritated with him perpetually talking about Concern, and he’d look at me and say: ‘Are you not interested then?’

‘I am, but there’s a limit.’

Aengus and Jack (and Jim, Jack’s twin, a banker) were three of seven siblings, three girls, four boys, brought up in a house on the Shelbourne road in Limerick. Mary, a public health nurse, is the eldest, Joe, the youngest, was in finance. Biddy, who passed away in 2003, was a homemaker.

Jim, Joe and Biddy have had fourteen children between them, and they too have become absorbed into the immediate clan so that, according to Sarah Finucane, one of Aengus’s devoted nieces, quite regularly there could be nineteen people, many times even more, around the Finucane table for Sunday dinner. ‘And don’t talk to me about Christmas ...’.

Despite, inevitably, the occasional internal spat, this is such a close-knit family, so fiercely loyal to each other that they can be imagined as a tightly packed quadrilateral phalanx, facing the four points of the compass, impermeable to invasion as they stand shoulder to shoulder and back to back. That, at any rate, is the initial impression.

Born on 26 April 1932, Aengus attended the Christian brothers’ school in Sexton Street, in that era when missionary priests and nuns of all cloths toured the classrooms, proselytising for vocations. Redemptorists, Dominicans, Medical Missionaries of Mary and others of many hues, including the Holy Ghost Fathers, bustled into dingy, grey classrooms and stood in front of dusty blackboards to talk not just about spiritual callings and service of the Creator through the particular ethos of their orders and congregations, but about altruism and the fulfilment of a life well lived. They spun tales of living in hot lands, far from the grim, dismal economy and drizzle of 1950s Ireland. They dazzled boys and girls from poor backgrounds with offers of an education, a career, a chance to be independent of the crushing rigidity of the class-ridden mono-culture then prevailing in Ireland. Crucially, they plucked chords in the hearts of young, idealistic and impressionable boys and girls impatient to be free, by offering adventure, planting the idea of doing God’s work in exotic locations.

In those times, if you couldn’t get into ‘teacher training’, the next best thing was a job for life in the civil service, with ‘establishment’ after five years and success in your oral Irish exam.

Forever after, you pushed a pen around a brown desk between four brown walls, squatting in some former colonial mansion in Dublin that had been honeycombed into cubicle-like offices. Maybe you got into an insurance company; or maybe a bank, if you were really lucky and had a relative who was ‘well got’. You went ‘home’ for the weekends where you met your future spouse at Macra1 functions or in the palaces of dreams - the barn-like dancehalls situated at rural crossroads. If you stayed in Dublin during those weekends, you danced and hunted the opposite sex in the Teachers’ Club, the National, Crystal or Ierne Ballrooms.

Meanwhile, the steady stream of answers to those calls ‘to enter’ had as much to do with escape and adventure as they had with accepting a vocation from the Divine. For many young men and girls, the faraway lands described by these vigorous and charming priests and nuns had up to then been pictured only in carefully curated stamp collections. In cramped, shared bedrooms all over the country, heads-together children negotiated over gorgeously vivid illustrations of butterflies, unusual animals and rare flowers in glowing colour: ‘One of my Nyasalands and one Swaziland and one of my Philippines for that one of your Singapores?’

What is more, these calls for vocations came at a time when, for the majority, a university education was an unattainable luxury.

But here, as rain splashed into puddles in yards outside the windows of their classroom, was confirmation, directly from the mouths of Holy Mother Church, that you could achieve the distinction of having letters after your name and respect in your town, village or townland. And even more exciting was the prospect of exploration of lands filled with beautiful colours under a constant yellow sun, all the while conquering souls for God.

During the first five or six decades of the twentieth century in Ireland, these aspects of becoming a priest or nun in a missionary order are absolutely recognised and acknowledged by contemporaries who entered with Aengus, and by Jack, too, who joined his brother five years later in the huge training seminaries of Kilshane and Kimmage.

In interview, when asked directly whether it was more important to him and to Aengus to go abroad to the missions or to become a priest, Jack responded instantly:

To us it was the same thing.

(You could have been a diocesan priest?)

Didn’t want to. From the very beginning I wanted to go to Africa. That was what attracted me to be a missionary priest.

(Why was that?)

We were influenced by the people who went before us. Limerick had quite a number of Holy Ghost priests, and these people came home on holidays. You’d meet them and mix with them, you heard their stories. That frontier approach – that’s what attracted. I had two cousins who were Dominicans, but I wasn’t interested in their lifestyle. They weren’t on the real missions, as we thought. We were going, as we thought, to the real missions. To Darkest Africa.

As it happened, one of these clerical-storytellers, to whom both Finucanes avidly listened, was Limerickman Bishop Joseph Whelan of the diocese of Owerri in the Nigerian state of Biafra. He was revered by his fellow Shannonside citizens for his missionary and humanitarian work. In those early days, none of the three, bishop or two future Holy Ghosts, could have known that they were to work together in the Biafran civil war and famine in the late 1960s, or that in the minds of the Irish public this catastrophe was to become associated for the rest of their lives with the Finucanes.

At this point, it might be interesting to look ahead a little by quoting some of the words given in interview by Donal Byrne, now a senior editor in the RTÉ newsroom, but who was at the time of the 1984 Ethiopian famine, a reporter with The Irish Times. With a party of journalists he travelled to Ethiopia with Concern to cover the 1984 famine, where he had his first taste of the fieldwork practices of the Finucanes, their staff and volunteers.

That famine had crashed memorably onto our TV screens, firstly via the work of Mike Wooldridge, the BBC’s East Africa correspondent, and shortly afterwards, to astonishing global effect, via Michael Buerk, whose reportage, along with the pictures of his cameraman, Mohamed Amin, spurred a worldwide response.

It wasn’t Donal Byrne’s first trip to cover a disaster; he had been abroad with other charitable organisations. And he had never been less than clear-eyed about ‘the missions’. Like us all, he had dropped pennies into collection boxes and had received an acknowledgment when the head of a small ‘black baby’ fixed to a spring on the top of the alms box wobbled his or her head in delighted gratitude at receiving such largesse.

This was to be Byrne’s first close encounter with Concern in general and with the Finucanes in particular, in this case Jack. He also encountered Aengus subsequently, and with what is now called, popularly the ‘helicopter view’ here is some of what he said:

What was called ‘the missions’ way back in the past always had some vague and quite questionable meanings for me. But when you were dealing with those Finucane guys – this is a very personal view – you could see they had decided that this was their vocation. It seemed to me that they were almost defrocked in the literal sense and that nothing was going to get in the way of that vocation. That’s how strong they were, what allowed them to manage politically, both nationally in Ireland and with governments in the strangest kinds of places with the strangest administrations. It was the first time I’d seen, at first-hand and close-up, what it meant to be a missionary in a modern context.

To Donal, this was an indication of how the Church had, at some point, ‘divided silently. (Yes I have a vocation, but my vocation is not to be sitting in a parochial house in Glenealy; my work is to go to the four points of the globe.)’

I‘m equally convinced that if these nuns and priests weren’t doing what they were doing abroad, they’d be gone out of the Church; they wouldn’t be part of any conventional set-up.

He believes that what was remarkable about the Finucanes is that they were ‘mavericks to begin with’, but that a lot of such individualists are useless in a crisis:

These were people who could handle a crisis with natural ability, talent, leadership and a natural diplomacy. I don’t think Jack, inasmuch as I knew him, would have the tolerance for sitting in endless meetings about how, in six months’ time, we might be able to do something. Crisis was what drove him. You could see it in him physically: the challenge was there, he was up to it.

It’s only since I began to think about what I might offer as my own thoughts that I began to think of Jack as a priest. Aengus too, although he wore his collar more and was more evidently a cleric at meetings and so forth. The collar helped him on occasions, and I think he knew it. When you’re selling something to Irish people, and you are there as a trusted man of the cloth, this caring, compassionate figure, wearing a clerical collar does help.

Again he goes back to that era, putting a context on the work of aid and charity organisations:

It’s only when I saw the scale of what was on the ground [in Ethiopia] and what had to be dealt with, I began to understand what was in play here. Their experience, for instance. They could do huge work with limited resources, and could affect and improve the lives of a large, large number of people and do it effectively and speedily.

And although I didn’t know them well enough to presume, my impression was that beneath this drive and determination was a spiritual motivation. If you were offered an enormous salary to do what they were doing, I don’t think you’d last a month.

There will be more from Donal Byrne presently.

The males in the Finucane family grew up to be big men; their grandfather was a blacksmith in Kilrush; he and his wife had nine sons. One of them, John, (known as Jack; to avoid confusion, let’s call him ‘Jack Senior’) became the father of Mary, Aengus, Patsy, Jack, Jim, Biddy and Joe, and was the only one of the nine who made 70 years of age.

Tom had what was generally known during that era as a ‘good job’ in the Department of Finance in Dublin.

As a group, the Finucanes are modest about their achievements. Tom Finucane, one of Jack Senior’s brothers, was head of the exchequer section of the Department of Finance. Professor Paul Finucane, one of Aengus’s and Jack’s nephews, is the foundation head of the graduate entry medical school at the University of Limerick. His brother Jim Finucane, another professor, is a noted endocrinologist at Beaumont Hospital. You get the picture. This was, and is, a high-achieving family.

Jack Senior, a committed Republican who was twice interned, worked for the London Steamboat Company, but finished his working life as company secretary at J. J. O’Toole’s, a firm of paper merchants, where until he retired he lived a simple life, cycling home for his dinner in the middle of the day.

A deeply devout Catholic, he took just two foreign trips in his lifetime: one to Lourdes, one to Rome, instead preferring to holiday with his family in Kilkee. He was a quiet man, and ‘contented’ by all accounts, including Patsy’s, who is interviewed while sitting in her small flat on the south side of Dublin. Allegedly retired from a life spent in education, she is busier than ever with pastoral and other work, including Ki massage, reflexology and counselling.

(Had their mother identified Aengus for a vocation?)

No, but our grandmother, Grandma Finucane, never doubted but that he would be a priest. It was a custom in that part of County Clare that the eldest became a priest.

She goes on to relate an extraordinary story she heard many times growing up. Aengus, she believes, knew it too because it involved him:

… and we did talk about it. I have a very vivid memory of one particular morning. Dad used to try to go to Kilrush to visit his mother once every six weeks, and when war came he had to go down by boat – the flour boat – from Limerick docks to Cappa pier.

This morning, Mum was getting us ready for school, we used to line up in the kitchen to have our hair brushed and so on. Dad came in and he was carrying his case. ‘I think I’ll go to Kilrush today.’

Mother stopped what she was doing. ‘What are you talking about? You were in Kilrush three weeks ago.’

And he said: ‘Yes, but I always said that if I got this urge, I’d answer it. I’ll go down to the docks after work, and if I can get on a boat, I’ll go. So if I’m not back, you’ll know I’ve gone.’

This, remember, was 1940s Ireland, where personal telephones were only for doctors, parish priests and bank managers.

So he went to Kilrush. It was November, as far as I remember. When he got to his mother’s house, she opened the door: ‘Jack, what are you doing? You’re not due at all!’

Anyhow, he stayed that first night, and when the second night came, decided to go and visit his aunt, his mother’s sister, who lived nearby. On leaving, he said to his mother: ‘You go to bed now, and I’ll bring you up hot milk when I get back.’ And when he got back, she was dead in the bed.

Clare people have this extraordinary devotion to the dead, and Dad always used to pray to his own father that his mother wouldn’t die alone.

She did, as it happened, but the crux of this story is that her son was there to take from her hand the envelope she was clutching. ‘In it was money for Aengus’s ordination.’

In Sister Patsy’s opinion, Aengus himself never doubted but that he was destined for the Church, and not just because of those exciting talks given in his classroom by the vocation-seeking clerics. ‘He was very religious as a child, very prayerful.’ Even when still a boy, alongside his passion for the hurling and football he played for his club, Treaty Sarsfields, he became involved in the Penny Dinners service run by the local conference of the St Vincent de Paul.

Again and again, interviewees of all hues, and not just Patsy or the other members of Aengus’s close family, made sure to emphasise that one of his most transparent traits was that, whatever the cause, when he was in, he was in. ‘We used to get a pain in the face with Penny Dinners, because if Aengus was involved in Penny Dinners we were all involved in Penny Dinners,’ says Patsy.

Liam Burke and John Leahy, friends and fellow Limerick men, both agree with this drive Aengus exhibited from a very early age and have seen it first-hand.

Burke, whose father had a small shop near where the Finucanes lived, now runs a photographic agency, Press 22, in the city. He became a friend of Aengus’s in the early 1980s when he travelled to various disaster areas in Concern countries of operation to capture images. He has supplied the organisation with these, free of charge, ever since. His iconic image of a boy carrying his little brother, (captioned ‘He’s not heavy, he’s my brother’)wassnapped in Ethiopia and was widely used by the organisation for many years to illustrate promotional and fundraising material.

Burke admired Aengus, not just personally, but for his ethos. They had long discussions about the poor. ‘I think Concern is the only organisation I know that wants to put itself out of business. That was Aengus’s philosophy.’

I remember being in the shop as a small boy and seeing children in their bare feet coming to take the rotten fruit and vegetables, and ham that was rank. This was the early 1960s, so this is how I know that Angela’s Ashes [a famous memoir of a poverty-stricken Limerick childhood by Frank McCourt, later filmed] was authentic. When he was young, Aengus would have seen this, and probably worse than this, a lot earlier. I think it made a lasting impression on him.

Incidentally, when in his later years he went to New York as honorary president of Concern US, Aengus met McCourt, who lived there and the two became firm friends.

John Leahy is a Limerick motor dealer. He was taken into the Finucane family circle by his friend Joe, Aengus’s brother. He says that Frank McCourt’s book did not exaggerate the abject poverty in certain areas of the city in the late 1930s and 1940s, even into the 1950s and early 1960s. He characterises Aengus’s boyhood work with the Penny Dinners as being a characteristic effort to do something about lifting the poor with ‘not a hand-out but a hand-up’; a phrase that resonated with him throughout his life and work.

Long before Aengus got to his work, however, there was the little matter of ten long years of priestly training.

From all of the siblings and very close friends, it is clear that during the Finucanes’ growing up it was their mother who held sway, setting the rules and running her household. Aengus, being the eldest son, being such a ‘good’ boy, so devout, religious and charitable, did she favour him? Spoil him?

According to Patsy:

I was never conscious of favouritism, and there was nothing in the way we were treated to indicate that. Mum would say: ‘They were all different, but I loved them all.’ It’s only looking back, I would think she probably did favour Aengus. He was very appealing, a very charming child, could get around anyone.

That quality of charm was taken with Aengus into adulthood. Patsy illustrates it with a story from much later, when all seven siblings were adults:

I was in the dining room, in the most comfortable chair in the house by the fire. It had always been called ‘Dad’s chair’. And I was sitting in it, and Biddy was sitting in Mum’s chair, when Aengus came into the room.

He could stand like a helpless child in the middle of the room looking around – Oh dear! Where am I going to sit?’ On this occasion, he was standing thus when his mother bustled in: Patsy! Stand up and let your brother sit down!’

Patsy: ‘Excuse me?’

Aengus: ‘You heard your mother speaking!’

And while everybody else would be running around, there he’d be, sitting in the best chair all evening!’

1Macra na Feirme, founded in 1944 and literally ‘sons’ or ‘stalwarts’ of the farm (or countryside) is a voluntary rural organisation running a nationwide network of clubs for young people between the ages of 17 and 35. Activities include sport, agriculture, travel, performing arts, community involvement and public speaking.

2

‘Terminus ad quem …

The goal was to get ordained and get to Africa’

– Father Mick Reynolds

Aengus Finucane was born energetic, channelling a lot of his early drive not just into Penny Dinners but physically into participation in sport. A fervent supporter of Munster rugby, (and Shannonside rugby club in particular) he was present in Thomond Park when the provincial team famously defeated the New Zealand All Blacks. According to informants ever after, in Cardiff, Twickenham, anywhere he could catch a match involving Ireland or his own team, when asked by neighbouring spectators where he was from, he never answered ‘Ireland’, or even ‘Limerick’, it was always ‘Munster’.

While still young and on the Gaelic pitch for Treaty Sarsfields, Aengus’s contribution to the team was not his finesse but his burly, charging presence. (In his turn, Jack played for the same club, ascending to selection by the Limerick Minor team in both disciplines.) At CBS in Sexton Street, the Christian Brothers count J. P. McManus, entrepreneur, philanthropist and racehorse owner, along with Aengus, as two of their star graduates. (And actually, on the joint accession to the rolls of Freemen of Limerick City, McManus presented Aengus and Jack with two magnificent silver horse sculptures, one each.)

By universal agreement of contemporaries and family, his time at the school inculcated in Aengus Cornelius Finucane a lifelong devotion to the Christian Brothers, evidenced by his whip-like defence of them as a group when they were attacked in print, in media or verbally in discourse as some members have been for proven abuse of the children in their care. He would reluctantly acknowledge that, yes, there did exist the odd vicious, sadistic member of that organisation – while continuing to have difficulty with the incontrovertible evidence of the perversion of a few. In general, however, to the day he died he held fast to the fact, also unarguable, that without the Brothers, for decades the state’s education of its young males would have been unconscionably lacking.

In later life, when in New York as honorary president of Concern US, most of the time he stoutly resisted all offers of hospitality and sponsorship of his accommodation at comfortable hotels in favour of a tiny, cell-like room in the Brothers’ house. On one occasion when she was in New York and visiting him, he brought Sarah, one of his devoted nieces, proudly to see it. Her reaction? ‘Jesus, Uncle Aengus! This would drive anyone to drink.’

‘Sure I’m gone out of here at 8.00 in the morning,’ he was taken aback, ‘and God knows what time I’d be home. And all I need is a bed ...’.

His bed from the time he left Sexton Street was, after his summer holidays, in the seminary of the Holy Ghost Fathers where he was to train for the priesthood for ten years.

Founded in Paris in 1703, the Congregation of the Holy Spirit, Congregatio Sancti Spiritus, abbreviated to ‘C.S.Sp.’ as a suffix to the names of its members, was set up by a young law student, Claude Poullart des Places, who gave up his chance at a career to dedicate his life to the service of the poor. He died at the age of 30 and, according to his wishes, was buried in a paupers’ grave.

To read the order’s history is to understand how deeply Aengus and Jack Finucane and their colleagues are imbued with the early mission of the founder: no outcast, criminal, slave, beggar, destitute, prostitute or person of lower caste is to be judged or is beyond the reach of love and ministry.

Now an international organisation, since its foundation the Holy Ghost Fathers have lived and worked in missionary parishes and schools all over the world. Many died in harness, as it were, succumbing to tropical diseases for which they were ill-prepared.

Up to the 1960s, Nigeria, and in particular the east of that country, had been the main destination for graduates from the Irish seminary in Kimmage. These Irish priests and their co-workers, the Holy Rosary Sisters, brought education and spread Roman Catholicism throughout that vast land by dint of a method that was quite simple: they took full advantage of the desire for education.

The Nigerian people, the Igbo tribe in particular, but most other tribes too, were desperate for learning. As a result, they were more than willing to convert to Catholicism, which was a requirement for access to the mission schools. ‘They flocked in,’ according to one of Aengus’s longest serving clerical friends, Father Mick Reynolds. ‘This was proselytising, pure and simple; it’s now treated with disdain in many quarters. It’s out of fashion.’

Father Reynolds and Father Dick Quinn, the second of Aengus’s close friends from those seminary days, were two of the fifty-five who entered the Holy Ghost Fathers’ training centre in 1959; forty-nine finished, including these three. As an indication of how times have changed, in 2014 there is just one seminarian going through Kimmage.

Jack’s seminary experience, five years behind his brother’s, was post-Vatican Two and although this may have coloured his thinking, according to him, the regime in Kimmage during his time there differed little from that of Aengus.

The closeness and value of the friendship between Aengus Finucane, Dick Quinn and Mick Reynolds survived until Aengus died. It survived the seminary experience, despite the best efforts of their superiors. With what has to be the biggest understatement within these pages, Father Quinn says: ‘We were not encouraged to become friends’:

Mick and Aengus and myself always got on together within the constraints, but you never got an opportunity to talk one-to-one to anybody. There was silence all day anyhow except for certain periods after lunch and after the evening meal. Then we went for a walk around the estate, which was very big. We went in threes.

The walk on a Tuesday – which was our recreation – was also in threes. The rule, in Latin, was: Nunquam Duo, Semper Tres – never two, always three. These walks started in the courtyard, with everyone milling around, until the first three names were called out, who then went off, hats and umbrellas at the ready – you had to have your hat on all the time – then the next three, then the next, and so on.

It has to be emphasised that during this era the Holy Ghost seminaries were not the only houses where this kind of regime was imposed. To varying degrees, it was at that time, apparently, the norm in all religious institutions.

For instance, in the 1950s, and well into the 1960s, Catholic seminarians and clergy were not allowed to attend theatres or cinemas. This being Ireland, they found an ‘Irish solution’: they watched the performances by standing in the wings, their view partially obscured by the ugly, unpainted backs of the canvas flats, with cross-hatched supporting lumber. Wearing full clerical garb, they peered through gaps in that scenery and got in the way of assistant stage managers, prompters, stagehands, and even the actors making entrances and exits, particularly any unfortunate who rushed off to make a quick change.

Actors were always aware of these off-stage hovering presences: of spectrally glowing clerical collars too big for thin necks, perhaps a glint of spectacles in the overspill of stage lights.

Dick Quinn, who loves opera and cinema and to whom culture is and was an essential part of life, keenly felt this particular stricture. He managed to watch ‘one or two’ performances of the d’Oyley Carte Opera Company, or at least the tops of the performers’ bobbing heads, from a perch in the Gaiety Theatre fly tower, a dangerous place for the inexperienced, not only because of the height, but because of its lacing of wires, ropes, pulleys and battens flying up and down as the scenes changed below.

The real absurdity, though, occurred at one stage when he was teaching Leaving Cert English to a class at St Mary’s in Rathmines. Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar was on the curriculum that year, and coincidentally the film based on the play and starring Marlon Brando came to town. ‘The whole school went out in buses to see it in the Ambassador Cinema, but I wasn’t allowed to go.’

One thing is clear: they all hated the weekly Chapter of Faults, a mass meeting where each student seminarian was expected to snitch on his fellows about transgressions of even the most minor rules.

‘It was a stupid exercise,’ says Mick Reynolds. ‘It had no meaning because everyone had to partake, and your turn came, and you were finding the most anodyne stuff: “Mr Finucane broke silence”; “Mr Quinn was looking around in chapel …”.’

Yes, they were all ‘Mister’, no first names allowed. Stuck for accusations on one occasion when asked to rat on ‘Mister Finucane’, Mick Reynolds cast around a bit and could only come up with: ‘He was a bit noisy.’

They were strictly forbidden to see each other during summer or other holidays when they were released back to their families, but this tenet, at least, was widely flouted, with no one willing to rat on others’ seaside swims with families not their own, or summer evening tennis matches with (perish the thought!) cousins who were girls. And had friendswho were not related….

In accumulation, these practices, these instruments of control, seemed designed to create dissent, suspicion and alienation amongst the troops, keeping them unsettled and therefore subservient.

‘You went through it for the terminus ad quem,’ say both priests, Reynolds and Quinn. The goal was to get to Africa.’

‘It was conditioning,’ Jack agrees. ‘We knew that, but in order to get ordained and get to Africa, these were the hoops you had to go through.’

Some of this stuff, however, was bizarre by any standards. According to Jack, ‘I failed Latin in my Leaving Cert, and when I went to Kimmage there was one professor teaching us ontology and cosmology who taught these subjects through Latin.’

Ontology is the philosophical study of the nature of being; cosmology is the study of the origin and evolution of the universe. (For the Holy Ghost student, study of the latter included creation by the deity.) ‘So here we were,’ Jack continues, ‘going through this exercise on a daily basis, and we didn’t understand a word of it, not a word, for two years.’

How did he manage to get through the exams in these subjects?

They were oral, through Latin. You learned phrases off, and if you heard a certain phrase in a certain question, you gave a certain answer. All part of the conditioning.

The most inhumane aspect of the seminary regime, though, was the treatment of those who couldn’t hack it. Dick Quinn again:

If anyone kicked over the traces they’d be politely asked to go. I’m not aware of anyone who kicked up and who stayed.

But when someone either decided to go or was asked to go, he was sworn to secrecy. Not allowed to tell anyone. We’d all go off to prayers at 6.00 in the evening, then straight to evening meal, and when we came back, the person had cleared his room and was gone. No goodbyes. Never came back. Just vanished.

Both priests, Father Dick Byrne and Mick Reynolds, talk about the utter liberation of graduation, ordination and then setting off for the missions. This next scene is widely reported by the clerics themselves, by the Finucane family and by many friends and acquaintances who heard the bones of the story from Aengus and others involved.

Each new group of Holy Ghost Fathers left for Africa initially by boat from the quays at Dublin’s North Wall. Having cast off, they gathered on the aft deck to watch Ireland recede into the mist. All agree on that.

Memories of what happened next diverge. Depending on whose is the most reliable, it occurred when the boat passed the Kish Lighthouse, or when it cleared the twelve-mile limit and entered international waters, or when those on deck could no longer see the twin chimneys of the Poolbeg power plant on the Great South Wall. But they all remember that on a signal they all, in concert, took off their black hats and threw them overboard. This expression of newfound freedom, if not its exact timing, has been permanently etched into communal memory.

During their separate interviews, both Mick Reynolds and Dick Quinn said something identical, later spontaneously echoed by Jack: ‘We entered at 18 and left at 18, even though we were actually 28.’ And then, said Jack, ‘when we got to Africa, we grew up very, very fast.’

It is difficult to credit now, but these young priests of their era were sent off with no training in Kimmage about anthropology, differing tribal traditions or religions, or what exactly to expect from the people they met when they got to their assigned Nigerian parishes.

Mick Reynolds adds:

It was training for spiritual life, not for day-to-day practical life in Africa. You had no clue as to what it was going to be like, and we went through ten years in Kimmage without any preparation for the missions as such. No one even told us that the first essential of the missionary is to be alive!

Those first French