Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

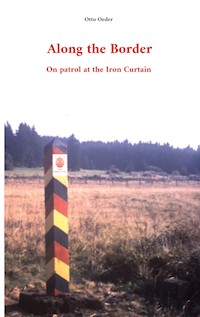

The author was born in a working-class family only a few days after the armistice in May 1945. After attending elementary school, he had to leave his parents' home at the age of 14 and learn the trade of butcher, before - at the age of 19 - successfully applying for the Bavarian riot police ("Bereitschaftspolizei"). In 1967 he was assigned to his post with the border police in Bad Steben in the Franconian Forest, right at the border with East Germany. He lived through the time of "divided Germany" as well as the peaceful unification of Germany. He retired from the police force in 2006. In this book, he recounts some of his experiences on the death strip of the former GDR, which deal with fugitives, spies and personal fates. The author wrote this book not so much as a memoir but to share with his (grand-) children his unique experience in historic times for Germany.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 75

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of contents

Foreword

Childhood and upbringing

Apprenticeships

A fateful internship

Starting Work life

The Inner-German border

Life inside the five km exclusion zone of the GDR

Escapes from the GDR to the "Golden West”

From a closed to an open border

The year of the opening of the border in 1989

The new reality

Stories and incidents on the border between East and West

Epilogue

Foreword

God did not want the author to be born a war child, which is why He waited until May 13, 1945, when the armistice had just been signed by the victorious powers, but weapons were still smoking from time to time and the Americans had just taken up quarters in his central Franconian market town of Markt Erlbach opposite his birthplace in the old district court. This meant for his parents and him from the beginning a hard future full of privation.

At the beginning he had neither shoes nor a school bag for school. It was not until the mid-fifties that things got better for him and he was able to earn some of his own food, at least by working for farmers as a child. He was denied the opportunity to attend high school because his parents could not afford the travel costs to the city 30 kilometers away or the books and exercise books. Therefore, at the age of 14, he had to leave home and learn the butcher's trade in another village, where he had board and lodgings and was no longer dependent on his parents. This tough childhood shaped him in such a way that he vowed to move up the ladder someday where he would have an easier time. His chance came when he applied to the Bavarian riot police and, after passing the recruitment test, was allowed to "move in" to the barracks in Würzburg on March 9, 1964.

After completing his training as a police officer, he reported to the border police station at Bad Steben in the Franconian Forest, right next to the Iron Curtain, in 1967. There, until the fall of the Wall in 1989, he performed border and general police duties on the "death strip" and received many a GDR refugee in Bavaria. The most joyful event, however, was the opening of the border, where he was present at several provisional border crossings in construction vehicles, which served as duty posts, and was able to experience how the Iron Curtain became more and more porous. In mid-1990, his post was renamed the Bavarian State Police Station. There he served as chief commissioner until his retirement in 2006.

I have written this book for my family, friends and acquaintances, and especially for my grandchildren, so that they can find out how a little "rascal" became a "border guard" at the "Iron Curtain" in the middle of Germany.

Childhood and upbringing

In 1945, when the Americans still occupied Thuringia and Saxony, I was born four days after the armistice in Markt Erlbach in Middle Franconia as the second child of a day laborer couple. After that, two more siblings saw the light of day in our small two-room rented apartment.

Until we left school, we grew up poor and modest, but well protected. Already as an eleven-year-old I was given to a farmer's family to work there for food and housing. There I had to do stable work early in the morning, even before school started, and field and forest work after school, and in the evening I had to do my homework on the side. I was not allowed to go to school sports in the afternoon, because working was more important. After I was beaten by the farmer's wife with a whip on my naked upper body because of something trivial (I was supposed to get off a cart with two cows, which was not fast enough for the farmer's wife), I ran away barefoot and fearfully went back to my parents, because I did not know whether I would be welcome at home or not. But thank God, they took their "prodigal son" back.

In the summer months we gathered dry wood and spruce cones in the forest or helped our parents with "digging sticks", collecting blueberries and forest mushrooms and for the tea in winter we picked lime blossoms and chamomile blossoms. In addition, we provided more than 20 rabbits with the necessary food, which we "plucked" by hand from meadows or fields and had to be careful that the farmers did not see us.

Apprenticeships

At the age of 14, I was "promised" by my parents to a master butcher in another town as an apprentice. After the school dismissal service in July 1959, the master butcher was already waiting in front of the church and took me with him. There I learned this trade for three years and came home to my family only once or twice a year. After successfully passing the journeyman's examination, I looked for work in my profession in the nearest large city and started working in a large butcher shop. In mid-1963, after my 18th birthday, I became aware of an advertisement from the Bavarian Riot Police asking for police recruits. At the time, I was due to be drafted into the German Armed Forces, so I applied for police service.

In the fall of 1963, I was then ordered to a two-day entrance examination at a barracks of the Bavarian Riot Police in Nuremberg. Of the eleven examinees, ten were high school students and of course I was the only one with 8 grades of elementary school and a journeyman's certificate as a butcher. After the written examinations on the first day, five candidates were sent home immediately because they had not passed the examination. The rest were allowed to stay and had to pass the sports, medical and oral exams the next day. After passing these last exams, I was already told that I would be allowed to "move in" to the police accommodation in Würzburg in March 1964. On March 9, I took the train to Würzburg and stood there at the station as an eighteen-year-old with my few belongings in a cardboard box and the draft notice quite poorly. But I knew how to help myself and had a cab take me to the police barracks. After dressing in uniforms, underwear and even a nightgown, I was taken to the barracks. The new arrivals were assigned to the individual platoons. I was assigned to the V-bike platoon, which is why I had to start training for my motorcycle license immediately after basic training and was also assigned a police "BMW machine" after passing the test.

The Author as a Kradmelder in 1964 in the Police Accommodation in Würzburg

Draft order 1964

After that, I had to take my class 3 police driver's license for official cars. On weekdays, from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., there were lessons in traffic law, criminal and civil service law, civics and other subjects. Special emphasis was placed on shooting, sports, self-defense, boxing, and swimming.

Every Wednesday, however, we went out on our motorcycles to the Rhön or the Spessart and were trained as motorcycle spotters or in traffic accident reporting. When we returned to our home barracks in the evening, we looked in our motorcycle suits as if we had just returned from a campaign. From top to bottom we were full of dirt and sand and the grains of sand crunched between our teeth. Tired and still fully dressed, we took a shower together with our motorcycle clothes, because the next day was roll call and everything had to be clean again. After such a ride, we fell asleep silently in our eight-bed room. Alone because of lack of oxygen, because the next morning you could "cut" the air.

Lunch break somewhere in the Spessart

At the same time, I had to take the typing and stenography exams. If you failed just one of these exams, everything was for nothing and you were discharged within 14 days without any ifs or buts, which I wanted to avoid, of course, because I knew how hard it was out there in the working world and the barracks had become my surrogate parental home. Here I had everything I needed: food, drink, friends and comrades. I swore to myself, "You'll stick with it here," and studied and studied as much as I could so that I would get good grades on the intermediate exams.