Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

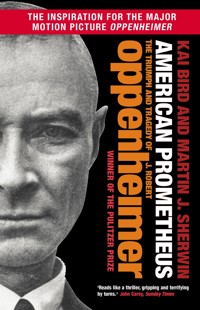

***THE INSPIRATION FOR OPPENHEIMER WINNER OF 7 OSCARS, INCLUDING BEST PICTURE, BEST DIRECTOR AND BEST ACTOR*** THE SUNDAY TIMES BESTSELLER WINNER OF THE PULITZER PRIZE FOR NONFICTION 'Reads like a thriller, gripping and terrifying' Sunday Times Physicist and polymath, as familiar with Hindu scriptures as he was with quantum mechanics, J. Robert Oppenheimer - director of the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb - was the most famous scientist of his generation. In their meticulous and riveting biography, Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin reveal a brilliant, ambitious, complex and flawed man, profoundly involved with some of the momentous events of the twentieth century.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1654

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

AMERICANPROMETHEUS

Kai Bird is a contributing editor at The Nation and the author of several biographies, including The Chairman, The Color of Truth, The Good Spy and The Outlier. He is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and a MacArthur Writing Fellowship.

Martin J. Sherwin was a Professor of History at George Mason University. His other books include A World Destroyed, winner of the Stuart L. Bernath and the American History Book prizes, and Gambling with Armageddon.

ALSO BY KAI BIRD

The Outlier: The Unfinished Presidency of Jimmy Carter

The Good Spy: The Life and Death of Robert Ames

Crossing Mandelbaum Gate: Coming of Age Between the Arabs and Israelis, 1956–1978

The Chairman: John J. McCloy, The Making of the American Establishment

The Color of Truth: McGeorge Bundy and William Bundy, Brothers in Arma

Hiroshima’s Shadow: Writings on the Denial of History and the Smithsonian Controversy (ed.)

ALSO BY MARTIN J. SHERWIN

Gambling with Armageddon: Nuclear Roulette from Hiroshima to the Cuban Missile Crisis

A World Destroyed: Hiroshima and its Legacies

For Susan Goldmark and Susan Sherwin

and in memory of Angus Cameron

and

Jean Mayer

First published in the United States of America in 2005 by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2008 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2009 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, 2005

The moral right of Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

A portion of this book previously appeared in a slightly different form in The Nation.

11

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-Book ISBN: 978-1-83895-719-3

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Modern Prometheans have raided Mount Olympus again and have brought back for man the very thunderbolts of Zeus.

—Scientific Monthly, September 1945

Prometheus stole fire and gave it to men. But when Zeus learned of it, he ordered Hephaestus to nail his body to Mount Caucasus. On it Prometheus was nailed and kept bound formany years. Every day an eagle swooped on him and devoured the lobes of his liver, which grew by night.

—Apollodorus, The Library, book 1:7, second century b.c.

CONTENTS

Preface

Prologue

PART ONE

1. “He Received Every New Idea as Perfectly Beautiful”

2. “His Separate Prison”

3. “I Am Having a Pretty Bad Time”

4. “I Find the Work Hard, Thank God, & Almost Pleasant”

5. “I Am Oppenheimer”

6. “Oppie”

7. “The Nim Nim Boys”

PART TWO

8. “In 1936 My Interests Began to Change”

9. “[Frank] Clipped It Out and Sent It In”

10. “More and More Surely”

11. “I’m Going to Marry a Friend of Yours, Steve”

12. “We Were Pulling the New Deal to the Left”

13. “The Coordinator of Rapid Rupture”

14. “The Chevalier Affair”

PART THREE

15. “He’d Become Very Patriotic”

16. “Too Much Secrecy”

17. “Oppenheimer Is Telling the Truth”

18. “Suicide, Motive Unknown”

19. “Would You Like to Adopt Her?”

20. “Bohr Was God, and Oppie Was His Prophet”

21. “The Impact of the Gadget on Civilization”

22. “Now We’re All Sons–of–Bitches”

PART FOUR

23. “Those Poor Little People”

24. “I Feel I Have Blood on My Hands”

25. “People Could Destroy New York”

26. “Oppie Had a Rash and Is Now Immune”

27. “An Intellectual Hotel”

28. “He Couldn’t Understand Why He Did It”

29. “I Am Sure That Is Why She Threw Things at Him”

30. “He Never Let On What His Opinion Was”

31. “Dark Words About Oppie”

32. “Scientist X”

33. “The Beast in the Jungle”

PART FIVE

34. “It Looks Pretty Bad, Doesn’t It?”

35. “I Fear That This Whole Thing Is a Piece of Idiocy”

36. “A Manifestation of Hysteria”

37. “A Black Mark on the Escutcheon of Our Country”

38. “I Can Still Feel the Warm Blood on My Hands”

39. “It Was Really Like a Never-Never-Land”

40. “It Should Have Been Done the Day After Trinity”

Epilogue: “There’s Only One Robert”

Author’s Note and Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Index

PREFACE

ROBERT OPPENHEIMER’S life—his career, his reputation, even his sense of self-worth—suddenly spun out of control four days before Christmas in 1953. “I can’t believe what is happening to me,” he exclaimed, staring through the window of the car speeding him to his lawyer’s Georgetown home in Washington, D.C. There, within a few hours, he had to confront a fateful decision. Should he resign from his government advisory positions? Or should he fight the charges contained in the letter that Lewis Strauss, chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), had handed to him out of the blue earlier that afternoon? The letter informed him that a new review of his background and policy recommendations had resulted in his being declared a security risk, and went on to delineate thirty-four charges ranging from the ridiculous—“it was reported that in 1940 you were listed as a sponsor of the Friends of the Chinese People”—to the political—“in the autumn of 1949, and subsequently, you strongly opposed the development of the hydrogen bomb.”

Curiously, ever since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Oppenheimer had been harboring a vague premonition that something dark and ominous lay in wait for him. A few years earlier, in the late 1940s, at a time when he had achieved a veritably iconic status in American society as the most respected and admired scientist and public policy adviser of his generation—even being featured on the covers of Time and Life magazines—he had read Henry James’ short story “The Beast in the Jungle.” Oppenheimer was utterly transfixed by this tale of obsession and tormented egotism in which the protagonist is haunted by a premonition that he was “being kept for something rare and strange, possibly prodigious and terrible, that was sooner or later to happen.” Whatever it was, he knew that it would “overwhelm” him.

As the tide of anticommunism rose in postwar America, Oppenheimer became increasingly aware that “a beast in the jungle” was stalking him. His appearances before Red-hunting congressional investigative committees, the FBI taps on his home and office phones, the scurrilous stories about his political past and policy recommendations planted in the press made him feel like a hunted man. His left-wing activities during the 1930s in Berkeley, combined with his postwar resistance to the Air Force’s plans for massive strategic bombing with nuclear weapons—plans he called genocidal—had angered many powerful Washington insiders, including FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and Lewis Strauss.

That evening, at the Georgetown home of Herbert and Anne Marks, he contemplated his options. Herbert was not only his lawyer but one of his closest friends. And Herbert’s wife, Anne Wilson Marks, had once been his secretary at Los Alamos. That night Anne observed that he seemed to be in an “almost despairing state of mind.” Yet, after much discussion, Oppenheimer concluded, perhaps as much in resignation as conviction, that no matter how stacked the deck, he could not let the charges go unchallenged. So, with Herb’s guidance, he drafted a letter addressed to “Dear Lewis.” In it Oppenheimer noted that Strauss had encouraged him to resign. “You put to me as a possibly desirable alternative that I request termination of my contract as a consultant to the [Atomic Energy] Commission, and thereby avoid an explicit consideration of the charges. . . .” Oppenheimer said he had earnestly considered this option. But “[u]nder the circumstances,” he continued, “this course of action would mean that I accept and concur in the view that I am not fit to serve this government, that I have now served for some twelve years. This I cannot do. If I were thus unworthy I could hardly have served our country as I have tried, or been the Director of our Institute [for Advanced Study] in Princeton, or have spoken, as on more than one occasion I have found myself speaking, in the name of our science and our country.”

By the end of the evening, Robert was exhausted and despondent. After several drinks, he retired upstairs to the guest bedroom. A few minutes later, Anne, Herbert and Robert’s wife, Kitty, who had accompanied him to Washington, heard a “terrible crash.” Racing upstairs, they found the bedroom empty and the bathroom door closed. “I couldn’t get it open,” Anne said, “and I couldn’t get a response from Robert.”

He had collapsed on the bathroom floor, and his unconscious body was blocking the door. They gradually forced it open, pushing Robert’s limp form to one side. When he revived, “he sure was mumbly,” Anne recalled. He said he had taken one of Kitty’s prescription sleeping pills. “Don’t let him go to sleep,” a doctor warned over the phone. So for almost an hour, until the doctor arrived, they walked Robert back and forth, coaxing him to swallow sips of coffee.

Robert’s “beast” had pounced; the ordeal that would end his career of public service, and, ironically, both enhance his reputation and secure his legacy, had begun.

. . .

THE ROAD ROBERT TRAVELED from New York City to Los Alamos, New Mexico—from obscurity to prominence—led him to participation in the great struggles and triumphs, in science, social justice, war, and Cold War, of the twentieth century. His journey was guided by his extraordinary intelligence, his parents, his teachers at the Ethical Culture School, and his youthful experiences. Professionally, his development began in the 1920s in Germany where he learned quantum physics, a new science that he loved and proselytized. In the 1930s, at the University of California, Berkeley, while building the most prominent center for its study in the United States, he was moved by the consequences of the Great Depression at home and the rise of fascism abroad to work actively with friends—many of them fellow travelers and communists—in the struggle to achieve economic and racial justice. Those years were some of the finest of his life. That they were so easily used to silence his voice a decade later is a reminder of how delicately balanced are the democratic principles we profess, and how carefully they must be guarded.

The agony and humiliation that Oppenheimer endured in 1954 were not unique during the McCarthy era. But as a defendant, he was incomparable. He was America’s Prometheus, “the father of the atomic bomb,” who had led the effort to wrest from nature the awesome fire of the sun for his country in time of war. Afterwards, he had spoken wisely about its dangers and hopefully about its potential benefits and then, near despair, critically about the proposals for nuclear warfare being adopted by the military and promoted by academic strategists: “What are we to make of a civilization which has always regarded ethics as an essential part of human life [but] which has not been able to talk about the prospect of killing almost everybody except in prudential and game-theoretical terms?”

In the late 1940s, as U.S.-Soviet relations deteriorated, Oppenheimer’s persistent desire to raise such tough questions about nuclear weapons greatly troubled Washington’s national security establishment. The return of the Republicans to the White House in 1953 elevated advocates of massive nuclear retaliation, such as Lewis Strauss, to positions of power in Washington. Strauss and his allies were determined to silence the one man who they feared could credibly challenge their policies.

In assaulting his politics and his professional judgments—his life and his values really—Oppenheimer’s critics in 1954 exposed many aspects of his character: his ambitions and insecurities, his brilliance and naïveté, his determination and fearfulness, his stoicism and his bewilderment. Much was revealed in the more than one thousand densely printed pages of the transcript of the AEC’s Personnel Security Hearing Board, In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer; and yet the hearing transcript reveals how little his antagonists had been able to pierce through the emotional armor this complex man had constructed around himself since his early years. American Prometheus explores the enigmatic personality behind that armor as it follows Robert from his childhood on New York’s Upper West Side at the turn of the twentieth century to his death in 1967. It is a deeply personal biography researched and written in the belief that a person’s public behavior and his policy decisions (and in Oppenheimer’s case perhaps even his science) are guided by the private experiences of a lifetime.

A QUARTER CENTURY in the making, American Prometheus is based on many thousands of records gathered from archives and personal collections in this country and abroad. It draws on Oppenheimer’s own massive collection of papers in the Library of Congress, and on thousands of pages of FBI records accumulated over more than a quarter century of surveillance. Few men in public life have been subjected to such scrutiny. Readers will “hear” his words, captured by FBI recording devices and transcribed. And yet, because even the written record tells only part of the truth of a man’s life, we have also interviewed nearly a hundred of Oppenheimer’s closest friends, relatives and colleagues. Many of the individuals interviewed in the 1970s and 1980s are no longer alive. But the stories they told leave behind a nuanced portrait of a remarkable man who led us into the nuclear age and struggled, unsuccessfully—as we have continued to struggle—to find a way to eliminate the danger of nuclear war.

Oppenheimer’s story also reminds us that our identity as a people remains intimately connected with the culture of things nuclear. “We have had the bomb on our minds since 1945,” E. L. Doctorow has observed. “It was first our weaponry and then our diplomacy, and now it’s our economy. How can we suppose that something so monstrously powerful would not, after forty years, compose our identity? The great golem we have made against our enemies is our culture, our bomb culture—its logic, its faith, its vision.” Oppenheimer tried valiantly to divert us from that bomb culture by containing the nuclear threat he had helped to set loose. His most impressive effort was a plan for the international control of atomic energy, which became known as the Acheson-Lilienthal Report (but was in fact conceived and largely written by Oppenheimer). It remains a singular model for rationality in the nuclear age.

Cold War politics at home and abroad, however, doomed the plan, and America, along with a growing list of other nations, embraced the bomb for the next half century. With the end of the Cold War, the danger of nuclear annihilation seemed to pass, but in another ironic twist, the threat of nuclear war and nuclear terrorism is probably more imminent in the twenty-first century than ever before.

In the post-9/11 era, it is worth recalling that at the dawn of the nuclear age, the father of the atomic bomb warned us that it was a weapon of indiscriminate terror that instantly had made America more vulnerable to wanton attack. When he was asked in a closed Senate hearing in 1946 “whether three or four men couldn’t smuggle units of an [atomic] bomb into New York and blow up the whole city,” he responded pointedly, “Of course it could be done, and people could destroy New York.” To the follow-up question of a startled senator, “What instrument would you use to detect an atomic bomb hidden somewhere in a city?” Oppenheimer quipped, “A screwdriver [to open each and every crate or suitcase].” The only defense against nuclear terrorism was the elimination of nuclear weapons.

Oppenheimer’s warnings were ignored—and ultimately, he was silenced. Like that rebellious Greek god Prometheus—who stole fire from Zeus and bestowed it upon humankind, Oppenheimer gave us atomic fire. But then, when he tried to control it, when he sought to make us aware of its terrible dangers, the powers-that-be, like Zeus, rose up in anger to punish him. As Ward Evans, the dissenting member of the Atomic Energy Commission’s hearing board, wrote, denying Oppenheimer his security clearance was “a black mark on the escutcheon of our country.”

AMERICANPROMETHEUS

PROLOGUE

Damn it, I happen to love this country.

ROBERT OPPENHEIMER

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY, February 25, 1967: Despite the menacing weather and bitter cold that chilled the Northeast, six hundred friends and colleagues—Nobel laureates, politicians, generals, scientists, poets, novelists, composers and acquaintances from all walks of life—gathered to recall the life and mourn the death of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Some knew him as their gentle teacher and affectionately called him “Oppie.” Others knew him as a great physicist, a man who in 1945 had become the “father” of the atomic bomb, a national hero and an emblem of the scientist as public servant. And everyone remembered with deep bitterness how, just nine years later, the new Republican administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower had declared him a security risk—making Robert Oppenheimer the most prominent victim of America’s anticommunist crusade. And so they came with heavy hearts to remember a brilliant man whose remarkable life had been touched by triumph as well as tragedy.

The Nobelists included such world-renowned physicists as Isidor I. Rabi, Eugene Wigner, Julian Schwinger, Tsung Dao Lee and Edwin McMillan. Albert Einstein’s daughter, Margot, was there to honor the man who had been her father’s boss at the Institute for Advanced Study. Robert Serber—a student of Oppenheimer’s at Berkeley in the 1930s and a close friend and veteran of Los Alamos—was there, as was the great Cornell physicist Hans Bethe, the Nobelist who had revealed the inner workings of the sun. Irva Denham Green, a neighbor from the tranquil Caribbean island of St. John, where the Oppenheimers had built a beach cottage as a refuge after his public humiliation in 1954, sat elbow to elbow with powerful luminaries of America’s foreign policy establishment: lawyer and perennial presidential adviser John J. McCloy; the Manhattan Project’s military chief, General Leslie R. Groves; Secretary of the Navy Paul Nitze; Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.; and Senator Clifford Case of New Jersey. To represent the White House, President Lyndon B. Johnson sent his scientific adviser, Donald F. Hornig, a Los Alamos veteran who had been with Oppenheimer at “Trinity,” the test on July 16, 1945, of the first atomic bomb. Sprinkled among the scientists and Washington’s power elite were men of literature and culture: the poet Stephen Spender, the novelist John O’Hara, the composer Nicholas Nabokov and George Balanchine, the director of the New York City Ballet.

Oppenheimer’s widow, Katherine “Kitty” Puening Oppenheimer, sat in the front row at Princeton University’s Alexander Hall for what many would remember as a subdued, bittersweet memorial service. Sitting with her were their daughter, Toni, age twenty-two, and their son, Peter, age twenty-five. Robert’s younger brother, Frank Oppenheimer, whose own career as a physicist had been destroyed during the McCarthyite maelstrom, sat next to Peter.

Strains of Igor Stravinsky’s Requiem Canticles, a work Robert Oppenheimer had heard for the first time, and admired, in this very hall the previous autumn, filled the auditorium. And then Hans Bethe—who had known Oppenheimer for three decades—gave the first of three eulogies. “He did more than any other man,” Bethe said, “to make American theoretical physics great. . . . He was a leader. . . . But he was not domineering, he never dictated what should be done. He brought out the best in us, like a good host with his guests. . . .” At Los Alamos, where he directed thousands in a putative race against the Germans to build the atomic bomb, Oppenheimer had transformed a pristine mesa into a laboratory and forged a diverse group of scientists into an efficient team. Bethe and other veterans of Los Alamos knew that without Oppenheimer the primordial “gadget” they had built in New Mexico would never have been finished in time for its use in the war.

Henry DeWolf Smyth, a physicist and Princeton neighbor, gave the second eulogy. In 1954, Smyth had been the only one of five commissioners of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) who had voted to restore Oppenheimer’s security clearance. As a witness to the star-chamber “security hearing” Oppenheimer had endured, Smyth fully comprehended the travesty that had been committed: “Such a wrong can never be righted; such a blot on our history never erased. . . . We regret that his great work for his country was repaid so shabbily. . . .”

Finally, it was the turn of George Kennan, veteran diplomat and ambassador, the father of America’s postwar containment policy against the Soviet Union, and a longtime friend and colleague of Oppenheimer’s at the Institute for Advanced Studies. No man had stimulated Kennan’s thinking about the myriad dangers of the nuclear age more than Oppenheimer. No man had been a better friend, defending his work and providing him a refuge at the Institute when Kennan’s dissenting views on America’s militarized Cold War policies made him a pariah in Washington.

“On no one,” Kennan said, “did there ever rest with greater cruelty the dilemmas evoked by the recent conquest by human beings of a power over nature out of all proportion to their moral strength. No one ever saw more clearly the dangers arising for humanity from this mounting disparity. This anxiety never shook his faith in the value of the search for truth in all its forms, scientific and humane. But there was no one who more passionately desired to be useful in averting the catastrophes to which the development of the weapons of mass destruction threatened to lead. It was the interests of mankind that he had in mind here; but it was as an American, and through the medium of this national community to which he belonged, that he saw his greatest possibilities for pursuing these aspirations.

“In the dark days of the early fifties, when troubles crowded in upon him from many sides and when he found himself harassed by his position at the center of controversy, I drew his attention to the fact that he would be welcome in a hundred academic centers abroad and asked him whether he had not thought of taking residence outside this country. His answer, given to me with tears in his eyes: ‘Damn it, I happen to love this country.’ ”*

ROBERT OPPENHEIMER WAS AN ENIGMA, a theoretical physicist who displayed the charismatic qualities of a great leader, an aesthete who cultivated ambiguities. In the decades after his death, his life became shrouded in controversy, myth and mystery. For scientists, like Dr. Hideki Yukawa, Japan’s first Nobelist, Oppenheimer was “a symbol of the tragedy of the modern nuclear scientist.” To liberals, he became the most prominent martyr of the McCarthyite witch-hunt, a symbol of the right wing’s unprincipled animus. To his political enemies, he was a closet communist and a proven liar.

He was, in fact, an immensely human figure, as talented as he was complex, at once brilliant and naïve, a passionate advocate for social justice and a tireless government adviser whose commitment to harnessing a runaway nuclear arms race earned him powerful bureaucratic enemies. As his friend Rabi said, in addition to being “very wise, he was very foolish.”

The physicist Freeman Dyson saw deep and poignant contradictions in Robert Oppenheimer. He had dedicated his life to science and rational thought. And yet, as Dyson observed, Oppenheimer’s decision to participate in the creation of a genocidal weapon was “a Faustian bargain if there ever was one. . . . And of course we are still living with it. . .” And like Faust, Robert Oppenheimer tried to renegotiate the bargain—and was cut down for doing so. He had led the effort to unleash the power of the atom, but when he sought to warn his countrymen of its dangers, to constrain America’s reliance on nuclear weapons, the government questioned his loyalty and put him on trial. His friends compared this public humiliation to the 1633 trial of another scientist, Galileo Galilei, by a medieval-minded church; others saw the ugly spectre of anti-Semitism in the event and recalled the ordeal of Captain Alfred Dreyfus in France in the 1890s.

But neither comparison helps us to understand Robert Oppenheimer the man, his accomplishments as a scientist and the unique role he played as an architect of the nuclear era. This is the story of his life.

*Kennan was deeply moved by Oppenheimer’s emphatic reaction. In 2003, at Kennan’s hundredth-birthday party, he retold this story—and this time there were tears in his eyes.

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

“He Received Every New Idea as Perfectly Beautiful”

I was an unctuous, repulsively good little boy.

ROBERT OPPENHEIMER

IN THE FIRST DECADE of the twentieth century, science initiated a second American revolution. A nation on horseback was soon transformed by the internal combustion engine, manned flight and a multitude of other inventions. These technological innovations quickly changed the lives of ordinary men and women. But simultaneously an esoteric band of scientists was creating an even more fundamental revolution. Theoretical physicists across the globe were beginning to alter the way we understand space and time. Radioactivity was discovered in 1896, by the French physicist Henri Becquerel. Max Planck, Marie Curie and Pierre Curie and others provided further insights into the nature of the atom. And then, in 1905, Albert Einstein published his special theory of relativity. Suddenly, the universe appeared to have changed.

Around the globe, scientists were soon to be celebrated as a new kind of hero, promising to usher in a renaissance of rationality, prosperity and social meritocracy. In America, reform movements were challenging the old order. Theodore Roosevelt was using the bully pulpit of the White House to argue that good government in alliance with science and applied technology could forge an enlightened new Progressive Era.

Into this world of promise was born J. Robert Oppenheimer, on April 22, 1904. He came from a family of first- and second-generation German immigrants striving to be American. Ethnically and culturally Jewish, the Oppenheimers of New York belonged to no synagogue. Without rejecting their Jewishness they chose to shape their identity within a uniquely American offshoot of Judaism—the Ethical Culture Society—that celebrated rationalism and a progressive brand of secular humanism. This was at the same time an innovative approach to the quandaries any immigrant to America faced—and yet for Robert Oppenheimer it reinforced a lifelong ambivalence about his Jewish identity.

As its name suggests, Ethical Culture was not a religion but a way of life that promoted social justice over self-aggrandizement. It was no accident that the young boy who would become known as the father of the atomic era was reared in a culture that valued independent inquiry, empirical exploration and the free-thinking mind—in short, the values of science. And yet, it was the irony of Robert Oppenheimer’s odyssey that a life devoted to social justice, rationality and science would become a metaphor for mass death beneath a mushroom cloud.

ROBERT’S FATHER, Julius Oppenheimer, was born on May 12, 1871, in the German town of Hanau, just east of Frankfurt. Julius’ father, Benjamin Pinhas Oppenheimer, was an untutored peasant and grain trader who had been raised in a hovel in “an almost medieval German village,” Robert later reported. Julius had two brothers and three sisters. In 1870, two of Benjamin’s cousins by marriage emigrated to New York. Within a few years these two young men—named Sigmund and Solomon Rothfeld—joined another relative, J. H. Stern, to start a small company to import men’s suit linings. The company did extremely well serving the city’s flourishing new trade in ready-made clothing. In the late 1880s, the Rothfelds sent word to Benjamin Oppenheimer that there was room in the business for his sons.

Julius arrived in New York in the spring of 1888, several years after his older brother Emil. A tall, thin-limbed, awkward young man, he was put to work in the company warehouse, sorting bolts of cloth. Although he brought no monetary assets to the firm and spoke not a word of English, he was determined to remake himself. He had an eye for color and in time acquired a reputation as one of the most knowledgeable “fabrics” men in the city. Emil and Julius rode out the recession of 1893, and by the turn of the century Julius was a full partner in the firm of Rothfeld, Stern & Company. He dressed to fit the part, always adorned in a white high-collared shirt, a conservative tie and a dark business suit. His manners were as immaculate as his dress. From all accounts, Julius was an extremely likeable young man. “You have a way with you that just invites confidence to the highest degree,” wrote his future wife in 1903, “and for the best and finest reasons.” By the time he turned thirty, he spoke remarkably good English, and, though completely self-taught, he had read widely in American and European history. A lover of art, he spent his free hours on weekends roaming New York’s numerous art galleries.

It may have been on one such occasion that he was introduced to a young painter, Ella Friedman, “an exquisitely beautiful” brunette with finely chiseled features, “expressive gray-blue eyes and long black lashes,” a slender figure—and a congenitally unformed right hand. To hide this deformity, Ella always wore long sleeves and a pair of chamois gloves. The glove covering her right hand contained a primitive prosthetic device with a spring attached to an artificial thumb. Julius fell in love with her. The Friedmans, of Bavarian Jewish extraction, had settled in Baltimore in the 1840s. Ella was born in 1869. A family friend once described her as “a gentle, exquisite, slim, tallish, blue-eyed woman, terribly sensitive, extremely polite; she was always thinking what would make people comfortable or happy.” In her twenties, she spent a year in Paris studying the early Impressionist painters. Upon her return she taught art at Barnard College. By the time she met Julius, she was an accomplished enough painter to have her own students and a private rooftop studio in a New York apartment building.

All this was unusual enough for a woman at the turn of the century, but Ella was a powerful personality in many respects. Her formal, elegant demeanor struck some people upon first acquaintance as haughty coolness. Her drive and discipline in the studio and at home seemed excessive in a woman so blessed with material comforts. Julius worshipped her, and she returned his love. Just days before their marriage, Ella wrote to her fiancé: “I do so want you to be able to enjoy life in its best and fullest sense, and you will help me take care of you? To take care of someone whom one really loves has an indescribable sweetness of which a whole lifetime cannot rob me. Good-night, dearest.”

On March 23, 1903, Julius and Ella were married and moved into a sharp-gabled stone house at 250 West 94th Street. A year later, in the midst of the coldest spring on record, Ella, thirty-four years old, gave birth to a son after a difficult pregnancy. Julius had already settled on naming his firstborn Robert; but at the last moment, according to family lore, he decided to add a first initial, “J,” in front of “Robert.” Actually, the boy’s birth certificate reads “Julius Robert Oppenheimer,” evidence that Julius had decided to name the boy after himself. This would be unremarkable— except that naming a baby after any living relative is contrary to European Jewish tradition. In any case, the boy would always be called Robert and, curiously, he in turn always insisted that his first initial stood for nothing at all. Apparently, Jewish traditions played no role in the Oppenheimer household.

Sometime after Robert’s arrival, Julius moved his family to a spacious eleventh-floor apartment at 155 Riverside Drive, overlooking the Hudson River at West 88th Street. The apartment, occupying an entire floor, was exquisitely decorated with fine European furniture. Over the years, the Oppenheimers also acquired a remarkable collection of French Postimpressionist and Fauvist paintings chosen by Ella. By the time Robert was a young man, the collection included a 1901 “blue period” painting by Pablo Picasso entitled Mother and Child, a Rembrandt etching, and paintings by Edouard Vuillard, André Derain and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Three Vincent Van Gogh paintings—Enclosed Field with Rising Sun (Saint-Remy, 1889), First Steps (After Millet) (Saint-Remy, 1889) and Portrait of Adeline Ravoux (Auvers-sur-Oise, 1890)—dominated a living room wallpapered in gilted gold. Sometime later they acquired a drawing by Paul Cézanne and a painting by Maurice de Vlaminck. A head by the French sculptor Charles Despiau rounded out this exquisite collection.*

Ella ran the household to exacting standards. “Excellence and purpose” was a constant refrain in young Robert’s ears. Three live-in maids kept the apartment spotless. Robert had a Catholic Irish nursemaid named Nellie Connolly, and later, a French governess who taught him a little French. German, on the other hand, was not spoken at home. “My mother didn’t talk it well,” Robert recalled, “[and] my father didn’t believe in talking it.” Robert would learn German in school.

On weekends, the family would go for drives in the countryside in their Packard, driven by a gray-uniformed chauffeur. When Robert was eleven or twelve, Julius bought a substantial summer home at Bay Shore, Long Island, where Robert learned to sail. At the pier below the house, Julius moored a forty-foot sailing yacht, christened the Lorelei, a luxurious craft outfitted with all the amenities. “It was lovely on that bay,” Robert’s brother, Frank, would later recall fondly. “It was seven acres . . . a big vegetable garden and lots and lots of flowers.” As a family friend later observed, “Robert was doted on by his parents. . . . He had everything he wanted; you might say he was brought up in luxury.” But despite this, none of his childhood friends thought him spoiled. “He was extremely generous with money and material things,” recalled Harold Cherniss. “He was not a spoiled child in any sense.”

By 1914, when World War I broke out in Europe, Julius Oppenheimer was a very prosperous businessman. His net worth certainly totaled more than several hundred thousand dollars—which made him the equivalent of a multimillionaire in current dollars. By all accounts, the Oppenheimer marriage was a loving partnership. But Robert’s friends were always struck by their contrasting personalities. “He [Julius] was jolly German-Jewish,” recalled Francis Fergusson, one of Robert’s closest friends. “Extremely likeable. I was surprised that Robert’s mother had married him because he seemed such a hearty and laughing kind of person. But she was very fond of him and handled him beautifully. They were very fond of each other. It was an excellent marriage.”

Julius was a conversationalist and extrovert. He loved art and music and thought Beethoven’s Eroica symphony “one of the great masterpieces.” A family friend, the philosopher George Boas, later recalled that Julius “had all the sensitiveness of both his sons.” Boas thought him “one of the kindest men I ever knew.” But sometimes, to the embarrassment of his sons, Julius would burst out singing at the dinner table. He enjoyed a good argument. Ella, by contrast, sat quietly and never joined in the banter. “She [Ella] was a very delicate person,” another friend of Robert’s, the distinguished writer Paul Horgan, observed, “. . . highly attenuated emotionally, and she always presided with a great delicacy and grace at the table and other events, but [she was] a mournful person.”

Four years after Robert’s birth, Ella bore another son, Lewis Frank Oppenheimer, but the infant soon died, a victim of stenosis of the pylorus, a congenital obstruction of the opening from the stomach to the small intestine. In her grief, Ella thereafter always seemed physically more fragile. Because young Robert himself was frequently ill as a child, Ella became overly protective. Fearing germs, she kept Robert apart from other children. He was never allowed to buy food from street vendors, and instead of taking him to get a haircut in a barber shop Ella had a barber come to the apartment.

Introspective by nature and never athletic, Robert spent his early childhood in the comfortable loneliness of his mother’s nest on Riverside Drive. The relationship between mother and son was always intense. Ella encouraged Robert to paint—he did landscapes—but he gave it up when he went to college. Robert worshipped his mother. But Ella could be quietly demanding. “This was a woman,” recalled a family friend, “who would never allow anything unpleasant to be mentioned at the table.”

Robert quickly sensed that his mother disapproved of the people in her husband’s world of trade and commerce. Most of Julius’s business colleagues, of course, were first-generation Jews, and Ella made it clear to her son that she felt ill-at-ease with their “obtrusive manners.” More than most boys, Robert grew up feeling torn between his mother’s strict standards and his father’s gregarious behavior. At times, he felt ashamed of his father’s spontaneity—and at the same time he would feel guilty that he felt ashamed. “Julius’s articulate and sometimes noisy pride in Robert annoyed him greatly,” recalled a childhood friend. As an adult, Robert gave his friend and former teacher Herbert Smith a handsome engraving of the scene in Shakespeare’s Coriolanus where the hero is unclasping his mother’s hand and throwing her to the ground. Smith was sure that Robert was sending him a message, acknowledging how difficult it had been for him to separate from his own mother.

When he was only five or six, Ella insisted that he take piano lessons. Robert dutifully practiced every day, hating it all the while. About a year later, he fell sick and his mother characteristically suspected the worst, perhaps a case of infantile paralysis. Nursing him back to health, she kept asking him how he felt until one day he looked up from his sickbed and grumbled, “Just as I do when I have to take piano lessons.” Ella relented, and the lessons ended.

In 1909, when Robert was only five, Julius took him on the first of four transatlantic crossings to visit his grandfather Benjamin in Germany. They made the trip again two years later; by then Grandfather Benjamin was seventy-five years old, but he left an indelible impression on his grandson. “It was clear,” Robert recalled, “that one of the great joys in life for him was reading, but he had probably hardly been to school.” One day, while watching Robert play with some wooden blocks, Benjamin decided to give him an encyclopedia of architecture. He also gave him a “perfectly conventional” rock collection consisting of a box with perhaps two dozen rock samples labeled in German. “From then on,” Robert later recounted, “I became, in a completely childish way, an ardent mineral collector.” Back home in New York, he persuaded his father to take him on rock-hunting expeditions along the Palisades. Soon the apartment on Riverside Drive was crammed with Robert’s rocks, each neatly labeled with its scientific name. Julius encouraged his son in this solitary hobby, plying him with books on the subject. Long afterward, Robert recounted that he had no interest in the geological origins of his rocks, but was fascinated by the structure of crystals and polarized light.

From the ages of seven through twelve, Robert had three solitary but allconsuming passions: minerals, writing and reading poetry, and building with blocks. Later he would recall that he occupied his time with these activities “not because they were something I had companionship in or because they had any relation to school—but just for the hell of it.” By the age of twelve, he was using the family typewriter to correspond with a number of well-known local geologists about the rock formations he had studied in Central Park. Not aware of his youth, one of these correspondents nominated Robert for membership in the New York Mineralogical Club, and soon thereafter a letter arrived inviting him to deliver a lecture before the club. Dreading the thought of having to talk to an audience of adults, Robert begged his father to explain that they had invited a twelve-year-old. Greatly amused, Julius encouraged his son to accept this honor. On the designated evening, Robert showed up at the club with his parents, who proudly introduced their son as “J. Robert Oppenheimer.” The startled audience of geologists and amateur rock collectors burst out laughing when he stepped up to the podium; a wooden box had to be found for him to stand on so that the audience could see more than the shock of his wiry black hair sticking up above the lectern. Shy and awkward, Robert nevertheless read his prepared remarks and was given a hearty round of applause.

Julius had no qualms about encouraging his son in these adult pursuits. He and Ella knew they had a “genius” on their hands. “They adored him, worried about him and protected him,” recalled Robert’s cousin Babette Oppenheimer. “He was given every opportunity to develop along the lines of his own inclinations and at his own rate of speed.” One day, Julius gave Robert a professional-quality microscope which quickly became the boy’s favorite toy. “I think that my father was one of the most tolerant and human of men,” Robert would remark in later years. “His idea of what to do for people was to let them find out what they wanted.” For Robert, there was no doubt about what he wanted; from an early age, he lived within the world of books and science. “He was a dreamer,” said Babette Oppenheimer, “and not interested in the rough-and-tumble life of his age group . . . he was often teased and ridiculed for not being like other fellows.” As he grew older, even his mother on occasion worried about her son’s “limited interest” in play and children his own age. “I know she kept trying to get me to be more like other boys, but with indifferent success.”

In 1912, when Robert was eight years old, Ella gave birth to another son, Frank Friedman Oppenheimer, and thereafter much of her attention shifted to the new baby. At some point, Ella’s mother moved into the Riverside apartment and lived with the family until she died when Frank was a young teenager. The eight years separating the boys left few opportunities for sibling rivalry. Robert later thought he had been not only an elder brother but also perhaps “father to him because of that age difference.” Frank’s early childhood was as nurturing, if not more so, than Robert’s. “If we had some enthusiasm,” Frank recalled, “my parents would cater to it.” In high school, when Frank showed an interest in reading Chaucer, Julius promptly went out and bought him a 1721 edition of the poet’s works. When Frank expressed a desire to play the flute, his parents hired one of America’s greatest flutists, George Barère, to give him private lessons. Both boys were excessively pampered—but as the firstborn, only Robert acquired a certain conceit. “I repaid my parents’ confidence in me by developing an unpleasant ego,” Robert later confessed, “which I am sure must have affronted both children and adults who were unfortunate enough to come into contact with me.”

IN SEPTEMBER 1911, soon after returning from his second visit to Grandfather Benjamin in Germany, Robert was enrolled in a unique private school. Years earlier, Julius had become an active member of the Ethical Culture Society. He and Ella had been married by Dr. Felix Adler, the Society’s leader and founder, and, beginning in 1907, Julius served as a trustee of the Society. There was no question but that his sons would receive their primary and secondary education at the Society’s school on Central Park West. The school’s motto was “Deed, not Creed.” Founded in 1876, the Ethical Culture Society inculcated in its members a commitment to social action and humanitarianism: “Man must assume responsibility for the direction of his life and destiny.” Although an outgrowth of American Reform Judaism, Ethical Culture was itself a “non-religion,” perfectly suited to upper-middle-class German Jews, most of whom, like the Oppenheimers, were intent on assimilating into American society. Felix Adler and his coterie of talented teachers promoted this process and would have a powerful influence in the molding of Robert Oppenheimer’s psyche, both emotionally and intellectually.

The son of Rabbi Samuel Adler, Felix Adler had, with his family, emigrated to New York from Germany in 1857, when he was only six years old. His father, a leader of the Reform Judaism movement in Germany, had come to head Temple Emanu-El, the largest Reform congregation in America. Felix might easily have succeeded his father, but as a young man he returned to Germany for his university studies and there he was exposed to radical new notions about the universality of God and man’s responsibilities to society. He read Charles Darwin, Karl Marx and a host of German philosophers, including Felix Wellhausen, who rejected the traditional belief in the Torah as divinely inspired. Adler returned to his father’s Temple Emanu-El in 1873 and preached a sermon on what he called the “Judaism of the Future.” To survive in the modern age, the younger Adler argued, Judaism must renounce its “narrow spirit of exclusion.” Instead of defining themselves by their biblical identity as the “Chosen People,” Jews should distinguish themselves by their social concern and their deeds on behalf of the laboring classes.

Within three years, Adler led some four hundred congregants of Temple Emanu-El out of the established Jewish community. With the financial support of Joseph Seligman and other wealthy Jewish businessmen of German origin, he founded a new movement that he called “Ethical Culture.” Meetings were held on Sunday mornings, at which Adler lectured; organ music was played but there were no prayers and no other religious ceremonies. Beginning in 1910, when Robert was six years old, the Society assembled in a handsome meeting house at 2 West 64th Street. Julius Oppenheimer attended the dedication ceremonies for the new building in 1910. The auditorium featured hand-carved oak paneling, beautiful stained-glass windows and a Wicks pipe organ in the balcony. Distinguished speakers like W. E. B. DuBois and Booker T. Washington, among many other prominent public personalities, were welcomed in this ornate auditorium.

“Ethical Culture” was a reformist Judaic sect. But the seeds of this particular movement had clearly been planted by elite efforts to reform and integrate upper-class Jews into German society in the nineteenth century. Adler’s radical notions of Jewish identity struck a popular chord among wealthy Jewish businessmen in New York precisely because these men were grappling with a rising tide of anti-Semitism in nineteenth-century American life. Organized, institutional discrimination against Jews was a relatively recent phenomenon; since the American Revolution, when deists like Thomas Jefferson had insisted on a radical separation of organized religion from the state, American Jews had experienced a sense of tolerance. But after the stock market crash of 1873, the atmosphere in New York began to change. Then, in the summer of 1877, the Jewish community was scandalized when Joseph Seligman, the wealthiest and most prominent Jew of German origin in New York, was rudely turned away, as a Jew, from the Grand Union Hotel in Saratoga, New York. Over the next few years, the doors of other elite institutions, not only hotels but social clubs and preparatory private schools, suddenly slammed shut against Jewish membership.

Thus, by the end of the 1870s, Felix Adler’s Ethical Culture Society provided New York Jewish society with a timely vehicle for dealing with this mounting bigotry. Philosophically, Ethical Culture was as deist and republican as the Founding Fathers’ revolutionary principles. If the revolution of 1776 had brought with it an emancipation of American Jews, well, an apt response to nativist Christian bigotry was to become more American— more republican—than the Americans. These Jews would take the next step to assimilation, but they would do it, so to speak, as deist Jews. In Adler’s view, the notion of Jews as a nation was an anachronism. Soon he began creating the institutional structures that would make it practical for his adherents to lead their lives as “emancipated Jews.”

Adler insisted that the answer to anti-Semitism was the global spread of intellectual culture. Interestingly, Adler criticized Zionism as a withdrawal into Jewish particularism: “Zionism itself is a present-day instance of the segregating tendency.” For Adler, the future for Jews lay in America, not Palestine: “I fix my gaze steadfastly on the glimmering of a fresh morning that shines over the Alleghenies and the Rockies, not on the evening glow, however tenderly beautiful, that broods and lingers over the Jerusalem hills.”

To transform his Weltanschauung into reality, Adler founded in 1880 a tuition-free school for the sons and daughters of laborers called the Workingman’s School. In addition to the usual subjects of arithmetic, reading and history, Adler insisted that his students should be exposed to art, drama, dance and some kind of training in a technical skill likely to be of use in a society undergoing rapid industrialization. Every child, he believed, had some particular talent. Those who had no talent for mathematics might possess extraordinary “artistic gifts to make things with their hands.” For Adler, this insight was the “ethical seed—and the thing to do is to cultivate these various talents.” The goal was a “better world,” and thus the school’s mission was to “train reformers.” As the school evolved, it became a showcase of the progressive educational reform movement, and Adler himself fell under the influence of the educator and philosopher John Dewey and his school of American pragmatists.

While not a socialist, Adler was spiritually moved by Marx’s description in Das Kapital of the plight of the industrial working class. “I must square myself,” he wrote, “with the issues that socialism raises.” The laboring classes, he came to believe, deserved “just remuneration, constant employment, and social dignity.” The labor movement, he later wrote, “is an ethical movement, and I am with it, heart and soul.” Labor leaders reciprocated these sentiments; Samuel Gompers, head of the new American Federation of Labor, was a member of the New York Society for Ethical Culture.

Ironically, by 1890 the school had so many students that Adler felt compelled to subsidize the Ethical Culture Society’s budget by admitting some tuition-paying students. At a time when many elite private schools were closing their doors to Jews, scores of prosperous Jewish businessmen were clamoring to have their children admitted to the Workingman’s School. By 1895, Adler had added a high school and renamed the school the Ethical Culture School. (Decades later, it was renamed the Fieldston School.) By the time Robert Oppenheimer enrolled in 1911, only about ten percent of the student body came from a working-class background. But the school nevertheless retained its liberal, socially responsible outlook. These sons and daughters of the relatively prosperous patrons of the Ethical Culture Society were infused with the notion that they were being groomed to reform the world, that they were the vanguard of a highly modern ethical gospel. Robert was a star student.

Needless to say, Robert’s adult political sensibilities can easily be traced to the progressive education he received at Felix Adler’s remarkable school. Throughout the formative years of his childhood and education, he was surrounded by men and women who thought of themselves as catalysts for a better world. In the years between the turn of the century and the end of World War I, Ethical Culture members served as agents of change on such politically charged issues as race relations, labor rights, civil liberties and environmentalism. In 1909, for instance, such prominent Ethical Culture members as Dr. Henry Moskowitz, John Lovejoy Elliott, Anna Garlin Spencer and William Salter helped to found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Dr. Moskowitz similarly played an important role in the garment workers’ strikes that occurred between 1910 and 1915. Other Ethical Culturists helped to found the National Civil Liberties Bureau, a forerunner of the American Civil Liberties Union. Though they shunned notions of class struggle, members of the Society were pragmatic radicals committed to playing an active role in bringing about social change. They believed that a better world required hard work, persistence and political organization. In 1921, the year Robert graduated from the Ethical Culture high school, Adler exhorted his students to develop their “ethical imagination,” to see “things not as they are, but as they might be.”*

Robert was fully aware of Adler’s influence not only on himself but on his father. And he was not above teasing Julius about it. At seventeen, he wrote a poem on the occasion of his father’s fiftieth birthday that included the line “and after he came to America, he swallowed Dr. Adler like morality compressed.”

Like many Americans of German background, Dr. Adler was deeply saddened and conflicted when America was drawn into World War I. Unlike another prominent member of the Ethical Culture Society, Oswald Garrison Villard, editor of The Nation magazine, Adler was not a pacifist. When a German submarine sank the British passenger ship Lusitania, he supported the arming of American merchant ships. While he opposed American entry into the conflict, when the Wilson Administration declared war in April 1917, Adler urged his congregation to give its “undivided allegiance” to America. At the same time, he declared that he could not label Germany the only guilty party. As a critic of the German monarchy, at the war’s end he welcomed the downfall of imperial rule and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. But as a fierce anticolonialist, he openly deplored the hypocrisy of a victors’ peace that appeared only to strengthen the British and French empires. Naturally, his critics accused him of pro-German sentiments. As a trustee of the Society and as a man who deeply admired Dr. Adler, Julius Oppenheimer likewise felt conflicted about the European war and his identity as a German-American. But there is no evidence of how young Robert felt about the conflict. His teacher at school in ethical studies, however, was John Lovejoy Elliott, who remained a fierce critic of American entry into the war.

Born in 1868 to an Illinois family of abolitionists and freethinkers, Elliott became a beloved figure in the progressive humanist movement of New York City. A tall, affectionate man, Elliott was the pragmatist who put into practice Adler’s Ethical Culture principles. He built one of the country’s most successful settlement houses, the Hudson Guild, in New York’s poverty-stricken Chelsea district. A lifelong trustee of the ACLU, Elliott was politically and personally fearless. When two Austrian leaders of the Ethical Culture Society in Vienna were arrested by Hitler’s Gestapo in 1938, Elliott—at the age of seventy—went to Berlin and spent several months negotiating with the Gestapo for their release. After paying a bribe, Elliott succeeded in spiriting the two men out of Nazi Germany. When he died in 1942, the ACLU’s Roger Baldwin eulogized him as “a witty saint . . . a man who so loved people that no task to aid them was too small.”

It was to this “witty saint” that the Oppenheimer brothers were exposed throughout the years of their weekly dialogues in ethics class. Years later, when they were young men, Elliott wrote their father: “I did not know how close I could get to your boys. Along with you, I am glad and grateful for them.” Elliott taught ethics in a Socratic-style seminar where students discussed specific social and political issues. Education in Life Problems was a required course for all of the high school students. Often he would pose a personal moral dilemma for his students, such as asking them if they had a choice between a job teaching or a job that paid more working in Wrigley’s chewing gum factory—which would they choose? During Robert’s years at the school, some of the topics vigorously debated included the “Negro problem,” the ethics of war and peace, economic inequality and understanding “sex relations.” In his senior year, Robert was exposed to an extended discussion on the role of “the State.” The curriculum included a “short catechism of political ethics,” including “the ethics of loyalty and treason.” It was an extraordinary education in social relations and world affairs, an education that planted deep roots in Robert’s psyche—and one that would produce a bountiful harvest in the decades to come.

. . .

“I WAS AN UNCTUOUS, repulsively good little boy,” Robert remembered. “My life as a child did not prepare me for the fact that the world is full of cruel and bitter things.” His sheltered home life had offered him “no normal, healthy way to be a bastard.” But it had created an inner toughness, even a physical stoicism, that Robert himself may not have recognized.

Anxious to get him out of doors and among boys his own age, Julius decided to send Robert, at the age of fourteen, to a summer camp. For most of the other boys there, Camp Koenig was a mountain paradise of fun and camaraderie. For Robert, it was an ordeal. Everything about him made him a target for the cruelties young adolescents delight in inflicting on those who are shy, sensitive or different. The other boys soon began calling him “Cutie” and teased him mercilessly. But Robert refused to fight back. Shunning athletics, he walked the trails, collecting rocks. He made one friend, who recalled that Robert was obsessed that summer with the writings of George Eliot. The novelist’s major work, Middlemarch, appealed to him greatly, perhaps because it explored so thoroughly a topic he found so mysterious: the life of the inner mind in relation to the making and breaking of human relationships.

Then, however, Robert made the mistake of writing his parents that he was glad he had come to camp because the other boys were teaching him the facts of life. This prompted a quick visit by the Oppenheimers, and subsequently the camp director announced a crackdown on the telling of salacious stories. Inevitably, Robert was fingered for tattling, and so one night he was carried off to the camp icehouse, stripped and knocked about. As a final humiliation, the boys doused his buttocks and genitals with green paint. Robert was then left naked and locked inside the icehouse for the night. His one friend later said of this incident that Robert had been “tortured.” Robert suffered this gross degradation in stoic silence; he neither left the camp nor complained. “I don’t know how Robert stuck out those remaining weeks,” said his friend. “Not many boys would have—or could have—but Robert did. It must have been hell for him.” As his friends often discovered, Robert’s seemingly brittle and delicate shell actually disguised a stoic personality built of stubborn pride and determination, a characteristic that would reappear throughout his life.

Back in school, Robert’s highbrow personality was nurtured by the Ethical Culture School’s attentive teachers, all of whom had been carefully selected by Dr. Adler as models of the progressive education movement. When Robert’s math teacher, Matilda Auerbach, noticed that he was bored and restless, she sent him to the library to do independent work, and later he was allowed to explain to his fellow students what he had learned. His Greek and Latin instructor, Alberta Newton, recalled that he was a delight to teach: “He received every new idea as perfectly beautiful.” He read Plato and Homer in Greek, and Caesar, Virgil and Horace in Latin.

Robert always excelled. As early as third grade, he was doing laboratory experiments and by the time he was ten years old, in fifth grade, he was studying physics and chemistry. So clearly eager was Robert to study the sciences that the curator at the American Museum of Natural History agreed to tutor him. As he had skipped several grades, everyone regarded him as precocious—and sometimes too precious. When he was nine, he was once overheard telling an older girl cousin, “Ask me a question in Latin and I will answer you in Greek.”