5,85 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reardon Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

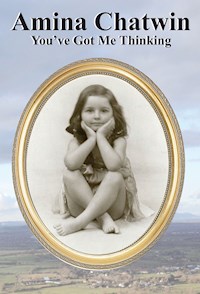

The life and times of Amina Chatwin. Toured the country with the renowned puppeteer Olive Blackham using hand-crafted wooden marionettes, many of which Amina made herself. Acknowledged expert in British iron working and smithing, well known to many blacksmiths around the world.

Awarded the Companionship of the Worshipful Company of Blacksmiths in recognition of her contributions to the craft of blacksmithing.

Chairman of the Historical Metallurgy Society.

President to the Gloucester Society for Industrial Archaeology and author of articles on local history and archaeology. Author 'Into the New Iron Age: Modern British Blacksmiths' Author of Cheltenham's Ornamental Ironwork, "It is impossible to overstate the importance of this book in the history of our craft: without it, there would be no comprehensive, accessible public record of the remarkable revival of artistic blacksmithing in the last quarter of the 20th century" - Dick Quinnell.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 304

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Published by

Reardon Publishing

PO Box 919, Cheltenham GL50 9AN

Amina in her garden

Copyright 2020

ISBN: 9781901037722

The autobiography of Amina Daphne Chatwin

1927 - 2016

With additional notes by the Editor

Julian André Rawes

Book and Cover Design by

Nicholas Reardon

Contents

Introduction

A Childhood in Cheltenham.

My Father's Parents.

My Father at Sea.

A Typhoon in the China Sea.

My Father Leaves the Sea.

The First Ron

The Roel Puppets.

I Discover Europe with Ron II.

To Madrid in [1956]: To the Second Journey.

I Go and Work in Paris, 1957-58

My Holiday to Greece

In 1959 I Stay with Arab Friends in Tunisia and Go to Rome to See Etruscan Tomb Paintings and Early Christian Mosaics.

I Visit Noelle in Rome.

The Following Saturday.

Looking at Palaeolithic Cave Paintings in the Pyrenees.

Industrial Archaeology Brings Ironwork into my Life.

Elston Boutique

Elston Studios New Year Festivities.

Archeometallurgy

Crossing Iceland 1966.

My First Visit to America 1982.

Travelling in Europe with American Blacksmiths 1997.

I Returned to Venice in 1998.

To Europe with American Blacksmiths in 1999.

Entering a New Century and Travelling in Europe with the Friends of the Museum 2001.

Northern Italy with the Bristol and Gloucester Archaeological Society 2000-2005.

In Venice with Ivan 2002.

Appendix

Local Shopping

Setting up the Flat over Elston Boutique

Setting up the Coach House

Marionettes

The MG Midget

Gold Mine

Jack Chalker

Cheltenham Festivals

Amina’s Family

Pedigree of Amina Chatwin’s Family by the Editor

Pedigree of Amina Chatwin’s Family by the Editor

The JCB

In a Hospital Waiting Room

Obituary to Amina by Julian Rawes

Introduction

Amina lived in the centre of Cheltenham all her life and it was in about 2010 that she informed me that she had started to record her early years as it might be of interest to people, especially as the character of the town had changed so much. Gone were most of the local shops, tradesmen and their families, gone were the ladies and gentlemen who had inhabited the large houses, people from the military and administrators who had chosen to retire to Cheltenham from across the empire; she observed these social and cultural changes with disquiet.

Amina had finally finished her major publication History of Iron Working in Britain, a project that she had worked on for many years (yet to be published). And now turned her attention to her own life, which included her childhood in the 1930's and early 40's, her many interests such as dancing, puppetry, art, wood carving, architecture, dressmaking, history, entertaining, early Christian art, iron-working, travels to Europe and America. She was a great observer and her memoirs are recorded with sincerity and openness, in which there is much sadness. Her book takes us up to her last trips to Italy in 2003-2004 and then ends abruptly. It is not known whether she intended to continue, her eyesight was failing through macular degeneration and she could no longer read and write without a powerful magnifying glass, a fact that greatly frustrated her. I offered to help her and by the time of her death we were part way through checking her final typescript copy. It was not an easy affair as Amina had very little patience.

After her death from a fall and hospital acquired pneumonia, I made myself a promise to publish this autobiography. The headings are almost entirely her own but the Appendix, and choice of photographs are mine.

I felt it necessary to add something about Amina's life during the twelve to fourteen years from her last entry up to 2016. Her travelling, especially when she had to give up her car, gradually diminished. She had also developed a heart condition and in later years often complained of lack of energy and being out of breath. She had little sign of arthritis and was a familiar figure around town until the end. She continued to put on her dinner parties until even these proved too much for her, the food was always superb and beautifully presented.

The dinner party

Amina had written books, articles and given talks for over 50 years, starting in 1960 on an article on ballet. It is possible to list only a few of them: a work on ballet that appeared 1961 in the Ballet Annual; Don't Fence me In, an article on Cheltenham ironwork, 1977; Antique and Ornamental Ironwork, Period Home 1985, Vol. 6, No,3 & 4; Cheltenham's Ornamental Ironwork, published in 1985, Into the New Iron Age in 1995; Some Gloucestershire Ironmasters, Journal of Historical Metallurgy Society, 1977; Cheltenham and the Men in their Flying Machines; a number of articles in the journal of the Cheltenham Local History Society; Looking into Europe, current Ironworking practises in Europe, 1998. And there is a surviving leaflet, which suggests that while still living in Wellington Street, Amina felt knowledgeable enough to give three talks, entitled Early Christian, Byzantine and Medieval Art, The Italian, French, Renaissance Art and The Impressionists.

Amina took a keen interest in Christianity and was an expert on early Christian art and custom and how it had formed. In later life, although an agnostic, she had joined the community at Christ church, her local parish church and in 2000, she helped to organise the Christ church Cheltenham Project 2000+. She went to bible study and talks and became part of the community. Amina seriously tried to have faith and to be a Christian, she was presumably spiritual but was intensely analytical and this need for proof made her critical of the Bible.

She could not accept that the Bible had all the answers without any backup from other sources or observations and could not simply rely on having faith in something. I remember an occasion when she had given a well-researched talk on early Christian art in which she stated that much of the early iconographic tradition of Christianity was derived from paganism. This connection with paganism had not gone down well with some members in the audience and she was asked not to speak on the subject again. She nevertheless found her visits to the church of great comfort.

Amina was accomplished in wood carving, as her puppets illustrate, and dress making; she also dabbled in painting and jewellery making. Her puppets have been donated to the National Puppetry Archive at Bridgnorth.

A self portrait

It is now clear that Amina had become a hoarder and her house was crammed with books, papers, clothes, slides, puppets, art, paintings, dress and craft making materials. She was fiercely independent and though her mind and interests were as sharp as ever, she still bought books and took an interest in international affairs but was losing the ability to sift through the mass of paperwork with which she had surrounded herself.

I dedicate my work on this book to Amina Chatwin whom I loved and admired, she will always be looked upon with affection.

Julian Rawes

A Childhood in Cheltenham.

In 2007 the architect who did such a good job on the rehabilitation of Christ Church, Malvern Road, said to me "I suppose you live in a Regency House" - well, I suppose I did - a coach house built in that period, but it was hardly what he had in mind. However, I had been born in a typical Regency terrace house.

The 1930s must have been one of the most uncomfortable periods in which to live in such a house. I was born in a house called St. Albans, in Wellington Street near the Town Hall in 1927. It had been named after the Duchess of that name, whose parents were of fairly humble origins and had lived in the nearby Cambray area. The Duchess was an actress Harriet Mellon, in the heyday of the Regency period and married Mr Thomas Coutts of the banking family, then after his death, as a very rich woman, married the Duke of St Albans.

Walter Vincent Chatwin, Amina's Father

My father was left £1000 by his aunt Amina (hence my name) and with it he bought the house shortly before I was born. The ground floor had probably once been two rooms with large wooden doors between them, an arrangement much used in Regency terrace houses. Down the side there was a long rather grand hallway, with an ornate plaster moulded ceiling, leading to a small toilet at the end. There was a fireplace at each end of the ground floor room and beside each a black rondel, inlaid, I think, with mother of pearl, and a handle to turn to ring a bell in the basement to call servants.

From the hall there was a tall flight of stairs leading to a shorter flight which led to three rooms on the first floor, two at the front and one at the back, above which were two small rooms.

When we began to live there the ground floor was given over to make a dancing school for my mother; we lived on the first floor, living room at the back and main bedroom and kitchen at the front. I should think all the rooms were about the same size, possibly the one at the back a little larger than the others.

Phyllis Elston, Amina's Mother

The only heating was a fire in the living room. There were gas fires in the bedrooms but these were never used unless someone was ill. In cold weather the house was extremely cold and talking to contemporaries recently we all clearly remembered the frost fronds of ice that used to form inside the window panes of our homes. The idea that one day we should live in houses heated by central heating was quite incomprehensible. Later the open fire in the living room was replaced by a stove type fire with doors at the front, which gave a better heat, instead of letting it all go up the chimney.

Looking back, I begin to ask myself where did we wash? I remember as a small child being bathed in front of the fire in the living room. At some point before World War II started, my father, who was a quantity surveyor and had been trained as an architect, built a bathroom on a flat roof at the top of the first flight of stairs, when a door replaced the original window. I can only think that before this we all washed at the sink in the kitchen.

Amina Daphne Chatwin

Presumably up to Edwardian times the people who lived in such houses had been waited on by servants who occupied the "servants quarters" in the basement, where there was a large pine dresser in the kitchen and a smaller one in the scullery. There would have been wash stands in the bedrooms each holding a large round china basin and a ewer (jug). I suppose the servants would have brought up hot water for washing. We did not realise it but by our time the servants had disappeared and the central heating had not yet arrived.

Amina Chatwin

When I was a baby I was for a time looked after by a Nurse Stenhouse. She must have been a rather odd character because one day she decided that she must go to London. With admirable care for her charge, and having no one to leave me with, she set off to walk to London pushing me in my pram. She wrote a note to my parents which was not discovered until late afternoon, probably when my father returned from work. At all events he set off in his car to find us and caught up with us at Northleach, so we had travelled quite a distance. I do not think that she remained long in our employ after this episode.

We took our holidays in Croyde Bay in north Devonshire. My father would drive us down and collect us at the end of the holiday. We stayed in the village where a stream ran down the side of the road. It must have made a tinkling noise because on returning home and lying in my bed at night, I missed it.

In the early years I was a small child usually in the charge of my grandmother. I am reputed to have gone into Mr Webbers at the village shop and asked for an ice cream cornet "but not too large". This was because the previous time the ice cream had fallen off onto the floor! Croyde was not far from Barnstaple where a local firm made pottery decorated with simple paintings and improving verses.

Amina Chatwin

For years we had a large jug bearing the verse:-

Do the work that's nearest

Though it's dull at whiles

Helping when you meet them

Lame dogs over stiles

Sometimes three or four young ladies from my mother's dancing school would accompany us. One year beach pyjamas became all the rage and some of the girls took the village by storm and were photographed by the local press.

On at least one occasion Ewart Norris was one of the party, a former beau of my mother's, who had been an aviator in the first world war and later worked in Africa looking after the Blue Posts Hotel, perhaps it was in Kenya. One day driving me in an open car, on a later holiday, he taught me a rather disreputable small verse:

There was a little sparrow

Flew all the way from Spain.

When half way on his journey

He met a great big hawk

Who plucked out all his feathers

And said "Walk you bugger walk."

They must have had a lot of fun, and an old photograph shows a rather sozzled looking Ewart being helped over a stile by half a dozen people. My mother must have regarded the beach as another form of stage and there are lots of photographs, over the years, of dancing and exhibition lifts.

Mostly I remember walking down through the sand dunes and looking for wild strawberries on the way to the beach. Yellow flowers were also common on the way covered with stripy yellow caterpillars. On one occasion when my grandmother and I were paddling, a large wave threw us off our feet, but we were righted again and suffered no harm. More than once we took our holidays in Highcliff, not far from Bournemouth; my father had a friend who had a "beach hut" there and every spring they went and put it up together.

Frances Day, Dorothy Blower, Celia Wilmore with Phyllis Chatwin sitting,

taken while at Croyde

Amina

Amina at riding school

It was the way of coastal holidays then, the shore was littered with wooden huts of all shapes and sizes and I suppose one stayed in a bed and breakfast and spent the day living in the hut and sitting in front of it or on the sands.

In later years we went for holidays to Berrow, near Burnham on Sea, and my mother and I learnt to ride at a local riding school, riding most mornings along the great expanse of foreshore.

Back in Cheltenham I would go to Parrys and it was in their indoor riding school in an old chapel that I learnt to jump. Today it has been replaced by the Regent Shopping Arcade.

My grandparents (my mother's parents) had a small shop facing onto the street at 55 Winchcombe Street, near the Pittville Gates. Inside, a corridor led to living quarters and on the right there was a counter.

I suppose it was more of a workshop than a shop. He was a civil and military boot maker and used to make beautiful hunting boots with pinky coloured tops. My grandfather sat on a low wooden chair making shoes and boots. Near him was a wooden container with shelves holding tools and maybe there was a cupboard underneath. Also near was a large terra-cotta jar (known as a crock) containing a noxious looking fluid; it was only water but had become dyed dark brown from the pieces of leather that were soaked in it. Under the counter there were shelves that held rolls of leather. At the back of the workshop were shelves on which stood "lasts" wooden models of customers feet used in making "made to measure" shoes. He also made what he uncompromisingly called "cripple boots". The craft had its own vocabulary, the "uppers" were the soft tops to the shoes and these were usually made by a different craftsman; sometimes if they were "brogues" they were decorated with a narrow border of cut out round holes. Sometimes we would go and collect the uppers from Sharpes warehouse. Sharpes had a shop in the Promenade, the one which still has a fine decorative iron balcony, and behind in County Court Road, they had a workshop. This was long and narrow and presided over by a foreman wearing, over his suit, an apron down to his ankles and a bowler hat. Later my mother would rent part of these premises as her first dancing school.

Sometimes a friend would sit and talk to my grandfather, selling him produce from his garden. Once we were all amused when after a whole summer of buying rhubarb which had by that time become coarse and green, he asked, in his rather lugubrious voice "Would you like some rhubarb?", as though it was the greatest treat in the world.

It must have been shortly before World War II another man joined my grandfather; he was a doctor displaced from somewhere in Eastern Europe. He was giving his services in return for instruction on how to make shoes, probably I should think "cripple boots". After a while he stopped coming and some years later returned to Eastern Europe. Who knows what political machinations went on there, but we were all sorry to know that he met an untimely end.

The corridor down the side of the workshop led to the hallway at the bottom of a flight of stairs. Here there stood a piece of furniture now singularly defunct - a hall stand. This one was made of dark wood with a mirror and places to put umbrellas and walking sticks, and a lot of pegs on which to hang coats. At one time a straw "boater" hat hung on one of the hooks with a stiff white collar round it. It was said that once in an absent-minded moment my grandfather had gone out wearing the hat still adorned with the collar.

Amina with her Elston grandparents

Stairs led to the kitchen and scullery below down in the basement. The kitchen had a large table, the usual built-in dresser and a pair of old steps, like stairs, which had once been used for getting into high Victorian beds. In the scullery there was a cylindrical boiler, and an iron mangle. The light was fairly dim and originally the artificial light would have been by gas mantle. The daylight came through the window which was enclosed by a skylight in which there was said to live a toad called Tomogos.

Back at the hall stand a door led into the living room where there were two chairs one on each side of the fireplace, a sideboard and a high cabinet, strangely said to have been made out of an old upright piano. The table was fairly large and only one of the leaves was open, later when it filtered down to me, I should find that it was a Regency Pembroke table they had purchased from an old man who had it from the Fleece Hotel, in the lower High Street, where it had been used with others fastened together (with little brass bolts underneath) to make a very long and large table at which farmers attending the weekly market would take their lunch. On a wall there was also a well known sentimental Victorian print of a large and a small dog called "Dignity and Impudence". Times could be hard and I know that there were sometimes days when they sat at that table with only bread and cheese for their lunch.

My grandmother was a dressmaker but she no longer had the roomful of "girls" that had once inhabited an upstairs room, though I was familiar with the old fashioned Singer treadle sewing machine that they had used. My mother used to say that as a child one of her games had been to take round the little drawers, built into the ends of the machine to hold spools of thread, elastic and so on, to "sell" to the girls, a form of playing "shop". At one point in her life my grandmother had been head of the workroom at Shires and Lances and in those days was paid I think it was 15/- a week. (At that time an average wage per week for a man was about 15/-, doubtless women's wages were less, so as head of the workroom she earned about the same as a man.)

Amina and grandfather Elston

My grandparent's house was opposite the Female Orphan Asylum in Winchcombe Street. When the orphans went on their annual holiday my grandmother, often with me in tow, went over to feed their cats. It was a large building with echoing wooden floors. I can still smell the freshly scrubbed pine tables in the kitchen where we mashed up the white fish, great collops that would cost a fortune today.

At the back there was a large playground with a few fowls railed in to one area. We used to throw them maize among the sweet smelling rosemary and fennel bushes.

Winchcombe Street was one of dwelling houses with the occasional "corner shop" interspersed with the small premises of craftsmen. As well as my grandfathers little shop, there was also at least one saddler, perhaps two, and on the opposite side of the street the School for the Blind where they made baskets.

There was also a Chinese laundry, as far as I know then the only Chinese business in the town. It was where one sent one's best washing like dress shirts. It was my grandmother who, if something was delayed and failed to come back on time learnt the term "ee-come ee-come", that passed into the family's vocabulary.

Sometimes my grandmother would take me down to the grocers halfway down the street, which stood out from a regency terrace. There was a great mound of butter on one of the counters where one's purchase was cut off and beaten up into shape with a pair of ribbed wooden bats (butter pats) and, I think for my benefit, it would sometimes be formed into a round shape and the picture of a cow impressed into the top. It was the only shop I ever remember where there was still sawdust over the floor.

Further down the street was Lockes Bakery and Drakes Store where we sometimes went to buy dress fabric. When you paid for your purchase the bill and the money were put into a long thin container which was placed in a hole in the wall where it was whizzed up to the office and would shortly return with the receipt and the change. The Famous was still using this system as late as 2008, I think as a tribute to the past. they continued to use them until they shut on January 5th 2013.

The Famous, a men's outfitters, was in the High Street and as a toddler I occasionally went there with my grandmother. We would go upstairs where the tailors sat cross-legged on a large table and my grandmother would ask them to work some buttonholes for her. She could work her own buttonholes but tailor's were better.

I do not think it was very often but sometimes my grandfather would take me to the Horse Repository, half way down Winchcombe Street where the horses were trotted round in a small circle to be auctioned.

I think he must have put me on his shoulders because it seemed that I looked down on to a sea of bowler hats and flat caps. The building had been the showroom of Miles the coach builder, but by my time this was gone.

A more regular outing was on Sunday mornings when he would call for me and we would walk together to Hewlett Road where his brother Harry had a little sweet shop and they would chat while I made a lengthy choice of some sweets or a bar of chocolate. I could buy a pennyworth of sweets served in a cone of paper, but my mother said when she was young you could get four different sorts for a penny, a farthing's worth of each.

We had special treats at Christmas time, on Boxing Day my grandfather would take me to see the Meet of the Hunt outside the Queen's Hotel. All up the Promenade people would be waiting at the edge of the road and we would watch the beautiful horses and men in pink coats with the hounds go by. Some of the ladies rode side saddle wearing black habits, top hats and veils. After drinking a stirrup cup they would all trot down the Promenade again; it was a great event, much enjoyed by everyone.

There is an elaborate fountain in the Promenade with a statue of Neptune and sea-horses, my grandfather could remember the man who modelled for Neptune, and many years later he would tell me that the man's name was Robin, though whether this was his Christian or surname I do not know. He was known as "Cock-Robin" because of his prowess with the ladies.

Another annual event was my grandmother taking me to Gloucester. We usually went by train and she carried a holly wreath to put on her sister Sally's grave. After we had visited the cemetery we went to the Bon Marché, had something to eat, and I would be taken to Santa's grotto, before going home by train. In those days they were proper trains, towering above you and emitting whistles and steam in all directions.

My grandfather's father had been a journeyman boot maker, from Devon I believe, and when he married, he and his wife had six sons and two daughters. They seem, very sensibly, to have operated their own personal apprenticeship scheme; all the boys were either tailors or shoemakers and the older ones trained the younger ones.

As a young man my grandfather was sent to London to train with one of his elder brothers. He used to recall how he had seen the remnants of the Light Brigade, who made the famous, or should I say infamous, charge during the Crimean War, sitting at some celebrations in Hyde Park. Also how Queen Victoria had driven past him in an open carriage and made him a little bow while he stood at the side of the road and took off his bowler hat to her.

Cars had no place in my grandparent's life but bicycles did. My grandfather must have been fairly athletic in his youth, he had gone in for walking races and also recalled the racing by "tall bikes" (commonly called penny-farthings) in Montpellier Gardens.

In their early married life they seem to have taken to bicycles in the big way. They rode out into the country, sometimes down to Lower Lode by the river at Tewkesbury. When my mother was a small child they had a caneware carriage for her which was attached behind one of the bicycles, and her feet rested on the picnic basket. To the end of his life my grandfather thought that the nicest outfit that a woman could wear was a long dark skirt, a white blouse, doubtless with "leg of mutton" sleeves and a straw boater hat.

My grandmother, whose maiden name was Webb, had been born in the Forest of Dean. She had a brother who was a baker and three sisters, Sally who married a man from Gloucester, a butcher I believe; Kate who emigrated with her husband Jack Dodwell to Toronto and Jinny who married Alf Trunkfield and emigrated to Vancouver. "Trunki", as they called him, had been in the cavalry in the First World War and I remember him saying that when they had to make a charge he would put his head down by his horse's neck, stick his sword out in front and shut his eyes.

Years later the Trunkfields would visit us when they had a chain of grocery stores. It was after World War II but food was still rationed. Trunkfield was a self entitled "meat eater" and any form of salad he regarded as "rabbit food". They brought a cabin-trunk full of food with them, but even so there was a certain resentment when he completely and obliviously ate every ones weeks ration of bacon for his breakfast one morning.

My Father's Parents.

I did not know my father's parents, they died before I was born. The Chatwins came from Birmingham industry, his father Walter was an accountant with the family firm. Walter’s father was Thomas, a mechanical engineer who lived at The Vale in Edgbaston and owned the Victoria Work’s in Great Tindal Street making stocks, dies and taps. The work had been awarded medals at exhibitions in Calcutta in 1884, Stockholm, 1886, Adelaide, 1887 and Melbourne in 1889.

My grandfather Walter married Susannah, née Jackson, of a family of yeomen farmers on the Cotswolds. As a young woman she had gone to Birmingham and worked in an office, whether this was the Chatwin office I do not know, but when the marriage took place it was generally thought that Walter had "married beneath him". Susannah had a brother Fred who worked Upcote Farm near Withington. Once in the fields he had fallen and broken one of his legs and by the time he had crawled back to the farm the bone was sticking out of the skin. Their wedding group was photographed in front of the farm and it was obviously an important occasion.

All the ladies were wearing enormous fashionable circular hats. Walter's sister Amina, I was named after her, was there but I am not sure that I see any other member of the Chatwin family.

The grass in the front of the house is clearly very long, the first lawn mower had been invented by Edwin Budding in 1830 at the Phoenix Works in Thrupp, Stroud, which was not far away, but they were obviously not yet in use on the local farms.

Walter and Susannah set up home, I was once told "in some style" in King's Norton, where my father, Walter Vincent, their only child, was born in 1899. It would have been a very different home to that of my Elston grandparents. From the few possessions that have come down to me I know there would have been fine china, silverware, and good antique furniture and clocks.

Later they lived in the Cotswolds, certainly at Stockwell Farm near Birdlip. It was probably Stockwell of which we had a photograph, with an open carriage drawn up in front of it; and doubtless from there that my father used to daily walk two miles each way to school at Cowley. He once told me that he used to like to go to a rise in the Gloucester to Cirencester road near a public house called "The Golden Hart" in Nettleton Bottom, to see if any of the cars, then beginning to come on to the roads, would break down on the hill. If they did he would help to push them up and hopefully be rewarded by a ride in the vehicle.

The last place they lived was Ingleside on Crickley Hill and my father finished his schooling at Northfield House in Cheltenham. Towards the end of the First World War he spent a short time in the RAF. I never heard anything about it except that he was once given the job of doling out stew to a vast number of servicemen on Salisbury Plain; it was then that he learnt a salutary lesson - there was sufficient except that there was none left for him!

His interest in cars was clearly forward looking, so it is no surprise that he was not drawn either to craftsmanship or industry but to a new 20th century occupation - he trained with Marconi as a wireless operator and joined the British Merchant Marine.

He certainly achieved a motorcycle by this time as I have a small photograph of him on it outside the house on Crickley Hill.

His mother became very ill in 1920 and by May her sisters were rallying round to look after her. She wrote a letter to her son on May 8th, "Aunt Evelyn went away today and Aunt Selina just arrived". They were hoping that "Aunt Ida will bring a nurse from Cirencester next week".

She was very weak but "still hoping to see you when you reach Glasgow". This was not to be as she died nine days later, aged only 54. The letter was the last he ever received from her and he kept it throughout his life.

Dad on motorcycle

My father must have been home for a while the following year as he took photographs at Browns Farm the home of his Aunt Ida. They show a shooting party, an unknown man, with my father, and a lanky schoolboy, Dudley. A younger son was Tim, who later became a baker at the best cake shop in Cheltenham (Maison Kunz, run by a Swiss, Mr Krier) and during World War II a fireman. There is also a photograph of my grandfather Chatwin; he is no longer the confident dark haired man at the centre of the wedding photograph, he has white hair, a large white moustache and a lost look. It is not surprising, he had lost his dearly beloved wife and his son was usually far away. He spent the end of his life staying at The Cross Hands in Brockworth. I have heard he was sometimes over fond of brandy, but who can blame him, it must have been the only comfort he had left.

Walter Chatwin

My Father at Sea.

I have a small photograph album made during my father's early years at sea. An Arab woman in a street in Algiers, temples in India, and an ox-cart in Calcutta. There are beach scenes in Saint-Malo and the docks at Dunkirk in 1921, and the Gatun and Pacific locks on the Panama Canal. The following year there are the Bengal Lancers riding along a path beside a river and timber elephants working in Moulmein, Burma.

Walter Vincent Chatwin in 1921 at Dunkirk

Panama Canal in early 1920's

There are a number of ships some of which he must have served on; he was on the Constadt in 1920-21, then the SS City of Calcutta, a passenger liner, from August 1921, which I think plied between Bombay and Calcutta. He was on the SS Warina in 1922-23. He wrote to his Aunt Ida in June 1923 saying . . .

SS City of Calcutta

"We are now quite settled down to the run between here and Bangkok (as far as I know until next spring). I like this part of the world quite well and have no desire to return to India". He then describes a visit to a friend who was second assistant on a rubber estate; it covered about 5,000 acres and the friend looked after 1,200 of them, the only European on the section. He was in charge of 200 Tamil labourers. He describes the average day in a planter's life: -