14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Penguin Verlag

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

A striking piece of contemporary history

David Ben Gurion and Konrad Adenauer stand as stalwarts of 20th-century politics, their legacies linked through German and Israeli history, revealing striking parallels. Despite ascending to the pinnacle of political power relatively late in life, both emerge as architects of a new statehood for their respective nations, carrying out pioneering work both domestically and on the diplomatic stage. Their bond deepens into friendship although they only met face-to-face on two occasions.

Michael Borchard recounts the intertwined lives of Ben Gurion and Adenauer in parallel, illuminating their seemingly impossible friendship and prompting reflection on the contemporary lessons that can be derived from these two towering figures.

With a foreword by grandsons Yariv Ben-Elieser and Konrad Adenauer.

- Erste englischsprachige Übersetzung

- Ein wichtiger Teil der deutsch-israelischen Geschichte

- Politisch und gesellschaftlich bis heute höchst relevante Doppelbiografie

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 625

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

About the author:

Born 1967 in Munich, Dr. phil. (Ph.D.), studied Political Science, Contemporary History and Public Law at University of Bonn, 1989–1994. Former member of the team of speech writers for the former Federal Chancellor Helmut Kohl and head of the speech-writing division for the former Minister-president of the State of Thuringia, Bernhard Vogel. From 2003–2014 director of department ‘Politics and Consulting’ in the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS). 2014–2017 resident representative of KAS in Israel. Since 2017 director of the department ‘References and Research Services/Archive for Christian Democratic Policy’ in KAS and as such responsible for the documents of the CDU.

About the translator:

Gwendolin Goldbloom, born in Rendsburg (Germany), read English studies and Islamic studies at Hamburg University. She has translated several books and numerous articles, often with a focus on the intellectual and political history of the Middle East. She lives in Surrey in southern England.

Michael Borchard

An Impossible Friendship

David Ben-Gurion and Konrad Adenauer

Translated by Gwendolin Goldbloom

Der Verlag behält sich die Verwertung der urheberrechtlich geschützten Inhalte dieses Werkes für Zwecke des Text- und Data-Minings nach § 44 b UrhG ausdrücklich vor. Jegliche unbefugte Nutzung ist hiermit ausgeschlossen.

The contents of this ebook are protected by copyright and contain technical safeguards to protect against unauthorized use. Removal of these safeguards or any use of the copyrighted material through unauthorized processing, reproduction, distribution, or making it available to the public, particularly in electronic form, is prohibited and can result in penalties under criminal and civil law.The publisher expressly reserves the right to exploit the copyrighted content of this work for the purposes of text and data mining in accordance with Section 44b of the German Copyright Act (UrhG), based on the European Digital Single Market Directive. Any unauthorized use is an infringement of copyright and is hereby prohibited.

First Edition

Copyright © 2024 by Penguin Verlag Munich,

A member of Penguin Random House Verlagsgruppe GmbH,

Neumarkter Str. 28, 81673 Munich

Originally published in 2019 in German under the title: Eine unmögliche Freundschaft: David Ben-Gurion und Konrad Adenauer by Herder Verlag

In cooperation with Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung / KAS

Editing: Karin Sirois

Cover Design: Büro Jorge Schmidt, Munich

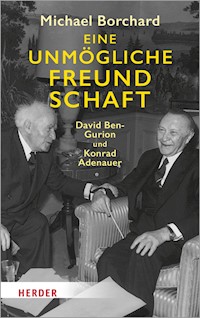

Using the picture: First meeting of Konrad Adenauer and David Ben-Gurion on the 35th floor of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York, 1960 (© Benno Wundshammer/bpk)

Typsetting: Uhl + Massopust GmbH, Aalen

ISBN 978-3-641-32817-7V001

www.penguin-verlag.de

Content

Yariv Ben-Elieser My Grandfather David Ben-Gurion

Konrad Adenauer My Grandfather Konrad Adenauer

Introduction

Konrad Adenauer and His Relations with the Jewish Community

Adenauer and Zionism – A ‘Rhenish Catholic Zionist’?

Adenauer the ‘Blutjude’ – Nazi Defamation

‘The Law and the Constitution Are Worth Nothing Now’ – Adenauer’s Dismissal

Existential Hardship after the Dismissal, and Jewish Support

‘Your Life Is Over in Any Case’ – Arrested by the Gestapo

‘A Madness Named Love of Zion’ – A Zionist Named David Grün

‘My Feet in the Dust and My Head in the Stars’ – The Journey to the Promised Land

‘An Ottoman Patriot’ – Representing Jewish Interests

The Dream of the Jewish Legion – Ben-Gurion the Soldier

‘Vladimir Hitler’ – The Struggle with the Revisionists

No Concern of Mine? – Ben-Gurion and the Rescue Attempts

‘Security Matters’ – Ben-Gurion and the Army

The ‘Divine’ Ben-Gurion – The Zionist Potential in the DP Camps

Ben-Gurion and Helena Goldblum – A Seminal Conversation

Excursus: Adolf Eichmann and the Process of Re-thinking the Holocaust

The Trial – A Confrontation with the Past

The Promised Land ‘Israel’ – Within Your Grasp

‘A Mourner Among the Joyous’ – Defending the Dream of Israel

The War of Independence – Ben-Gurion’s Successes as a General

Excursus: Creative Thinking in Times of Need – Ben-Gurion Rice and Adenauer Bread

Mass Immigration and Help from Germany

Israel and Adenauer – A ‘First Immediate Sign’

A ‘Remarkable Precedent’ – Israel’s Right to Compensation

Israel and Germany – The First Unofficial Official Encounter

A Detour via the Americans – An Unsuccessful Attempt

Crimes in the Name of the German People – A Declaration with Consequences

A Key Figure – Nahum Goldmann and the Restitutions

Goldmann and Adenauer – The First Encounter in London

Before the Negotiations – A Political ‘Showdown’ in the Knesset

Why Renounce That Which Is Ours? – A Difficult Debate

Begin’s Battle of Life and Death – ‘Adenauer Is a Murderer’

‘Serving My Conscience’ – Begin and the Attack on Adenauer

A Necessity – Mobilising Support

A Tightrope Act – The Narrative of the ‘Other Germany’

A ‘Running Mate’ for Reconciliation – Adenauer and Franz Böhm

A Suicide Mission – The Dilemmas of the Negotiations

Abs and Schäffer – Opponents of Negotiations?

The Limited Economic Capacity – A Chimera?

A ‘Private’ Mission in Paris – The Way Out of the Crisis

Fritz Schäffer’s Resistance – a Political Dilemma?

A ‘Special and Significant Day’ – Signing the Agreement in Luxembourg

Adenauer – An ‘Instrument of World Jewry’ and ‘Puppet of the West’?

The Last Act of Luxembourg – Ratifying the Agreement

After the Agreement – The Next Act: Diplomatic Relations?

Adenauer’s Germany – A ‘Camouflage for Neo-Nazism’?

Secret Journey Through the Snow – A Historic Event in the Dark

‘He Is Older’ – A Special Summit in New York

Ben-Gurion Gets Down to Business – A ‘Moral’ Proposal

Now We Are Talking Global Politics – Two Statesmen and Their View of the World

Missing From the List – Antisemitism in Germany

Fear of Consequences? – Germany and Diplomatic Relations

The Eichmann Trial and Globke – A Threat to Relations?

‘Our Nazis’ in Egypt – A Crisis Threatening Relations

He Is Ill and Exhausted – Ben-Gurion and His Resignation

Another Meeting with Adenauer? – Ben-Gurion and the Failed Attempt

Establishing Relations? – The Last Attempt at Perfecting the Rapprochement

Erhard Takes Over – The Start of Diplomatic Relations

Adenauer, Ben-Gurion and Power – The Patriarchs’ Rearguard Battles

A Special Invitation from Israel – After Difficult Times

The Journey to Jerusalem – With Mixed Feelings

An Honorary Doctorate for the ‘True Friend of Israel’ – Adenauer in Rehovot

‘I Am Leaving Tomorrow’ – Scandal and a Flaming Row in Jerusalem

One of the ‘Most Wonderful Moments of My Life’ – Adenauer in Israel

‘Israel Is the Tree of Life of Culture’ – Adenauer’s Positive Messages in Israel

Adenauer in Yad Vashem – ‘This Gripped Me Profoundly’

‘Voices from Cologne in Israel’ – A Special Encounter

The Second and Last Encounter – Adenauer Visits Ben-Gurion in the Kibbutz

Adenauer and Ben-Gurion – Safe Havens from Politics

‘His Old Self’ – Reactions to the Journey

‘Nix zo kriesche – Nothing to Cry About’ – The Patriarchs Pass into Eternity

Excursus: Friendship among Statesmen – An Illusion?

‘Don’t Do Anything Foolish While I’m Dead’ – Lasting Effects of the Friendship

A Bigger Germany after Reunification – A Threat to Israel?

Military Aid Driving Popularity – Israel and German Submarines

Can There Ever Be Normal Relations? – There Can Never Be Normal Relations!

Endnotes

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Image Part

Picture Credits

Index of Persons

Yariv Ben-Elieser My Grandfather David Ben-Gurion

My grandfather made a dream come true that was not his alone but also the dream of millions of Jews: the foundation of the State of Israel! Considering the difficult circumstances in which the genesis of the state took place, this historic event is nothing less than a miracle. ‘Anyone who doesn’t believe in miracles is not a realist’, my grandfather once said. David Ben-Gurion was a realist. He was a man of determination and firm purpose. This was the vital precondition for him to be able to realise this vision that Theodor Herzl had already pursued so passionately. The ‘miraculous’ foundation of the state did not, however, solve the problems. On the contrary, the challenge to preserve this hard-won achievement, to secure the existence of this threatened state and its inhabitants, was only beginning at the time and has not been completely accomplished to this day.

My grandfather knew that we must not wait for miracles to happen but that we must do our utmost to demand and work towards their implementation. It was this insight that enabled him to think the unthinkable. One aspect of the unthinkable was to talk with the nation that brought such unimaginable suffering and everlasting sorrow upon the Jewish people: to talk with Germany! David Ben-Gurion, to be sure, was never guided by pragmatic considerations of realpolitik alone but always by moral imperatives, too: He found it unbearable that the nation of murderers should become the heir of the murdered as well, and it was of great importance to him that there should be compensation for at least a fraction of the stolen property. He found it just as unbearable, however, that the sons and daughters of the perpetrators became victims themselves, as it were, by being held directly responsible for the deeds of their fathers and mothers, for which they are not actually responsible themselves. Besides the foundation of the State of Israel, this will forever remain his particular achievement: that he was able to muster this remarkable attitude, which put him years ahead of his fellow countrymen, such a short time after the Shoah and against understandable and simultaneously very pronounced resistance, and that he succeeded in convincing his country of the necessity to overcome the deep and seemingly unbridgeable gulf of German actions, and to reach out a hand to Germany.

With his foreign politics, my grandfather laid the foundation stone for German–Israeli relations which, while they will never be normal, are now so warm, cordial, and full of mutual trust as would have been hardly imaginable during my grandfather’s lifetime. This would not have been possible had not David Ben-Gurion found in Konrad Adenauer a counterpart who was his equal as a visionary, in creativity and firmness of purpose, but also as to his moral integrity. Every image that exists of David Ben-Gurion and Konrad Adenauer together, beginning with my grandfather’s meeting with the German federal chancellor in New York, and later in Sde Boker during Adenauer’s visit to Israel, show how much warmth, how much openness, and how much trust existed between the two men. The fact that Konrad Adenauer visited my grandfather and my grandmother Paula in this place in the Negev desert that meant so much to my grandfather, and where he spent the twilight years of his eventful life, is symbolic of the special relationship between the two men.

Our family was amazed again and again at just how similar the two gentlemen actually were, in spite of their very different appearance. In situations in which literally everything had to be redesigned, both were forced to devise a wealth of ideas and leadership far beyond the average. The foundations of the respective states meant that both were faced with considerable challenges at an advanced age when others have long settled down to enjoy their well-earned retirement. Both were realists and pragmatists possessed of a clearly defined moral compass.

Without the help Germany provided for Israel at the time, the establishment of the state and securing of Israel’s existence would have been very difficult, and maybe not even possible. It may well be beyond doubt that in his political approach to Israel, a realpolitiker of Konrad Adenauer’s stature was looking after his own interests. These included the necessity to return Germany to the circle of respected nations in the eyes of the wider European and international public. However, Konrad Adenauer displayed – and my grandfather profoundly admired this – the deeply felt moral duty to provide at least a certain degree of compensation, and the will to atone for something that cannot really be atoned for. Just how much he was guided by this moral dimension may be inferred from the fact that time and again, politically he went beyond what was expected by the negotiations.

The courage it took for the two statesmen to sometimes tread controversial paths is admirable, as this was always linked to the effort of mobilising support for their policies against a majority of the population. The prime example is the military cooperation initiated under David Ben-Gurion’s and Konrad Adenauer’s governments, which met with considerable resistance in the populations of both countries. Nowadays it is at the heart of the friendship between the two countries. The same is true of the scientific cooperation which both statesmen supported with particular commitment. The fact that Israel is part of a science and research region shared with the European Union, from which both sides benefit immensely, is also thanks to the two gentlemen.

I am delighted that this book endeavours not only to investigate the friendship between my grandfather and Konrad Adenauer separately, presenting the parallels in their respective lives, but also to enquire into the impact these special relations have to this day. I fondly remember how the author of this book, in his capacity as the head of the Adenauer Foundation’s office in Israel, asked me on the occasion of the visit of Konrad Adenauer’s grandson Patrick Adenauer to recreate the famous photo taken in New York in March 1960 in the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in Jerusalem. It was more than just a ‘publicity gag’. This recreated photo featuring the grandsons symbolises that subsequent generations are absolutely duty bound to preserve the inheritance of David Ben-Gurion and Konrad Adenauer and to support the rapprochement of the two states as well as prevent the estrangement of the two peoples. As this book builds such a bridge to the present, I hope it will enjoy a broad readership.

Yariv Ben Elieser

Konrad Adenauer My Grandfather Konrad Adenauer

I have been to Israel six times: the first time with a group of Knights of the Holy Sepulchre, twice with the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, once with a group of friends from Cologne led by the Cologne Jewish couple Daniel and Esther Gormanns who were friends with all members of the group, once with a group of friends of the Museum Ludwig led by its then director Marc Scheps, and once on the occasion of a Jewish wedding in the Gormanns family. During these journeys I have come to know and love many ancient cities, places sacred to Jews, Christians, and Muslims, the coast, the mountains, the lakes, and the rivers. Twice during these journeys, I visited Kibbutz Sde Boker, the last abode of David Ben-Gurion and his wife Paula. I have visited their house and above all their graves on the edge of the picturesque Negev Desert. On these occasions, I felt far removed – into the past and into the future. These graves, their simplicity and unique location, breathe the unforgettable spirit of eternity.

The images of the two meetings between Ben-Gurion and my grandfather on 14 March 1960 in the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York and on 9 May 1966 in Sde Boker are engraved on my mind like sacred icons, even though I was not present. At the time of the first meeting, I was 15 years old, and at the time of the second I was a fifth-semester law student at the university of Freiburg im Breisgau. I was aware of the extraordinary significance of these encounters, although in 1960 I did not know anything of the agreements reached during them. I was already familiar with the 1952 Luxembourg Restitution Agreement. I did not yet know, however, that the Irgun and, by implication, Menachem Begin were behind the assassination attempt on my grandfather in 1952. I considered the Restitution Agreement to be absolutely essential and have never been able to understand how anyone could vote against it in the Bundestag (Federal Parliament). On the one hand, my grandfather was not a man of drama and of expressing his feelings, and thus not someone to publicly fall on his knees. On the other hand, he certainly did not pursue this agreement for reasons of foreign policy alone but because he was profoundly convinced that Germany had to do something for Israel and the Jews on a material level as well. The dead could not be brought back to life again, but it was possible to do something for their relatives and descendants in Israel and their representative in the form of the newly founded State of Israel where many persecuted persons had found refuge. One could show them penitence and repentance. This was done not by the perpetrators but rather by the nation of which they were part. David Ben-Gurion and my grandfather signed the agreement, which had been negotiated by Nahum Goldman, against vehement resistance in their own ranks and their respective countries. It was the tentative beginning of reconciliation. One of its late and lasting effects is that Germany considers it part of its raison d’état to be on Israel’s side and to stand up for it.

It was a sign of reconciliation and personal friendship that cannot be praised enough that Ben-Gurion, despite his advanced age, came to Bonn for the German Bundestag’s memorial celebration for my grandfather on 25 April 1967, and that he walked to the Bundestag as it was a Jewish holiday. This image went around the world. On this occasion, I saw Ben-Gurion personally. Until then I had only known him from cinema newsreels and newspapers.

In the 1960s Israel was a favoured summer holiday destination among secondary school pupils in Cologne. They did not, however, go on holiday but went to work on a kibbutz. These visits were prepared in an introduction into the character of the State of Israel and its inhabitants as well as life there, held in Bad Sobernheim in the Palatinate. I knew and know many girls and boys who undertook these journeys joyfully and successfully at the time and who reported back from Israel with enthusiasm. Among them was my cousin Bettina Adenauer, the eldest daughter of my uncle Max Adenauer in Cologne. During his tenure as the city’s Oberstadtdirektor (head of the city’s administration executive) from 1953 to 1965, he had actively supported the exchange plans submitted by his education deputy Johannes Giesberts (1953–1974). The Gesellschaften für Christlich-Jüdische Zusammenarbeit (The German Coordinating Council of Christian-Jewish Cooperation), of which I am a member, continues to award the Giesberts-Lewin-Prize annually. The Eichmann trial, which began in 1961 in Jerusalem, fascinated and perturbed all of us. Eichmann was defended by Robert Servatius, a lawyer from Cologne.

Of importance to me personally was during this early time that one Good Friday evening, my parents’ very close friends Paul Ernst and Thea Bauwens introduced my close family to Willy Gormanns and his wife, a Jewish couple who had just returned to Germany from Israel. Willy Gormanns had been a close friend of our ‘uncle’ (as we called him) Paul Ernst since their school days. As a result, we are now neighbours and close friends of the couple’s son and his wife, whom I mentioned before.

A number of years ago I met a descendant of David Ben-Gurion’s on the occasion of a discussion meeting hosted by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation in Sankt Augustin. In the conference room of our Rhöndorf trust, the Bundeskanzler-Adenauer-Haus, a portrait of my grandfather painted by the Israeli artist Pinhas Litvinovsky (1894–1985) is on display. A copy is in the possession of the City of Cologne. These paintings were given to my grandfather as a present in 1963.

In my grandfather’s breakfast room in his Rhöndorf home, which is looked after by our trust and open to visitors, there is a silver-mounted Torah scroll featuring the symbols of the Twelve Tribes of Israel and Moses’ law tablets on the outside, and a dedication by Nahum Goldmann inside in commemoration of the conclusion of the Luxembourg Agreement on 10 September 1952.

In recognition of my efforts as my father Konrad Adenauer’s assistant in the execution of my grandfather’s legacy and its transfer into the aforementioned trust, I was given an album with the Israeli postage stamps dating from 1948 to 1955. I cherish it greatly. I believe that it was originally a gift from the Israeli government to my grandfather. My grandfather’s visit to Israel became possible only once diplomatic relations had been established under Ludwig Erhard. This was not done during my grandfather’s time as Germany was particularly considerate of the diplomatic relations with Arab countries at the time.

I have been told a number of times that David Ben-Gurion and my grandfather also talked about their families when they met in New York. My grandfather is said to have told the following anecdote: He once asked me, his grandson Konrad, what profession I would like to have when I grew up. When I said ‘Bundeskanzler!’, he replied that it was really not possible for there to be two federal chancellors.

Konrad Adenauer

Introduction

The contrast between the great public ‘performances’ on the stage of German–Israeli relations could not be any more pronounced. The first act of this initially difficult ‘marriage of convenience’ takes place in 1952 at a heavy table of impressive size, the very piece of furniture in the Cercle Municipal of the City of Luxembourg at which, usually, weddings are contracted and unions based on love celebrated. During the encounter of the two delegations, however, love is the least of the emotions. A chilly atmosphere accompanies the meeting, as is to be expected just over seven years after the German crimes against humanity. Those present hover between careful – face-saving – stagecraft and unavoidable emotional tension. The German–Israeli historian Dan Diner appositely called this ‘ritual distance’[1]. A stage set, scrutinised by the ‘audience’ in Israel and the ‘audience’ in Germany, who are observing with scepticism and consternation the ‘play’ being performed on the shared stage.

The agreement bears a name that refers to something entirely unimaginable at this early point in time: ‘Wiedergutmachungsabkommen’ means ‘agreement to make amends’. It is signed without speeches, without any personal exchanges. On the one side of the ceremonial table the German Federal Chancellor and Foreign Minister Konrad Adenauer, on the other side his Israeli counterpart Moshe Sharett, the latter with ‘trembling lips’[2] and ‘deathly pale’[3], as the German Jewish Social Democrat member of the Bundestag Jakob Altmaier, barely hiding his own emotion, describes the Israeli politician. Absolute silence.

How different the second act of the ‘performance’: In March 1960, barely eight years later, a room on the 35th floor of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, founded long ago by German immigrants some streets south of Central Park in New York, is the setting for the picture that is to this day the icon of the rapprochement between Germany and Israel. It shows the founding fathers of Israel and the Federal Republic of Germany, David Ben-Gurion and Konrad Adenauer, the former 73 and the latter 84 years of age. They meet – besieged by hordes of curious journalists – in a relaxed, apparently even cordial atmosphere, with not a trace of demonstrative distance: smiling faces, the Israeli patriarch placing his hand on the German chancellor’s arm. The statement made by the photograph is clear even to the uninformed observer: two gentlemen between whom the chemistry is obviously right and who are at ease with each other. ‘There is in all probability no more symbolic image of reconciliation than that of the two representatives of the nations of victims and perpetrators sharing a friendly handshake’[4], the scholar of Judaism Michael Brenner accurately assesses the scene. An image that is so very sensational because it implies normality where normality cannot yet exist.

Entirely different yet again was the third act in 1966, at the same time the second (and last) personal encounter of the two gentlemen: two men who call each other ‘friend’ not only in their letters but also during this encounter in the land of the forefathers. Shared hours in the Kibbutz Sde Boker in the heat of the desert. Greeting each other with a warm embrace. The smaller man and the tall man, both obviously enjoying meeting each other once again. Smiling gentlemen sharing a bottle of wine, seated at a table laid with a white tablecloth. Curious faces looking through the windows of the simple building from outside, trying to catch a glimpse of the prominent guests of honour. Hordes of journalists hoping for the photo of their lifetime so intrusively as to almost sour the pleasant atmosphere, held back by the efforts of Paula Ben-Gurion, the host’s wife.

Taken individually, all three events have become positive icons of German–Israeli relations, especially the first encounter of the two statesmen in New York: Not one essay, book, or newspaper article on the special relationship that does not include the famous photo from the classy New York hotel, and the present book has clearly not resisted this temptation, either. A photo that has become so influential not least because the warmth with which the two statesmen meet each other is nothing less than a small miracle. And for once this does not refer to the miracle that a German and an Israeli statesman could meet with such warmth such a short time after the Shoah, and that over the decades this rapport has developed into a special relationship and – yes, indeed – friendship of the nations as well.

No, the miracle referred to is that of the personal ‘compatibility’ of the two patriarchs. How can it be that two human beings who are so different, who have travelled such different roads and possess different temperaments, with different priorities and different points of view, can become so evidently close in such a short time? How can it be that the Catholic conservative from the Rhineland and the Socialist Jewish sceptic and Zionist David Ben-Gurion established such a cordial rapport? How can it be that during only two personal encounters, the two men set a standard that continues to have such a lasting impact on the relations between the two countries?

The question of questions, however, is of course how they were able to meet as representatives of their respective states in an atmosphere of such mutual trust, against the background of the Shoah, the most incomprehensible crime against humanity; how they succeeded in establishing such a profound and resilient relationship based on their mutual trust against all resistance even in their own countries. How is it possible, barely two decades after the industrially organised murder of more than six million Jews, to garner understanding for the rapprochement of the two states in the country that for a long time to come would stamp its passports with the qualification ‘with the exception of Germany’[5]?

Innumerable – sometimes conflicting – biographies have been written about Konrad Adenauer and David Ben-Gurion, as have studies of German–Israeli relations.[6] The extraordinary relationship between the two statesmen, too, has been highlighted in numerous contributions and essays focussing on their encounters. Where, then, is the gap into which the present study can fit?

A book that correlates the lives of the two men, that begins by pointing out the parallels in their respective biographies, making these the basis for attempts at explaining why the two were able to trust each other immediately, a book that retraces the two historic encounters of 1960 and 1966 and the ‘preparations’ that led up to them, and that assesses the friendship between the two statesmen with regard to the present and the future of German–Israeli relations – such a book is as yet outstanding.

Looking at the present can be a risk for historians – for some, indeed, it is a taboo – but for political scientists it is almost a necessity. This is all the more true in the case of a topic such as Israeli–German relations that possesses ‘eternal actuality’. The high degree to which the two states have become entwined, the close cooperation on all fields, the fact that the partnership is characterised not only by the historical links between the two states and by shared interests, but also by an intensive connection, indeed: friendship between the civil societies – all this would be difficult to imagine without the achievement of Konrad Adenauer and David Ben-Gurion. Their friendship, which appeared impossible on the catastrophic pile of rubble left behind on German and European soil by the Nazis’ disastrous dictatorship, has grown into an ‘impossible friendship’ between the two countries. The uncomfortable question of how secure or endangered the legacy established and bequeathed by the two politicians is must not be left out of this study, either.

Konrad Adenauer and His Relations with the Jewish Community

Scholars and journalists have speculated time and again just how sincere the German federal chancellor’s engagement for reconciliation between Germany and the Jews, and for rapprochement between Germany and Israel genuinely was, on balance. Of course, his innumerable statements on the moral duty to contribute to the survival of Israel with financial benefits have been heard, but they are hardly ever reported without a demonstrative reference to Adenauer’s pragmatism, his astuteness, and his determination to use the relations with the Jews and with Israel to buy the ‘ticket’ that would allow Germany to become a respected member of the international family once again. How great was this need really, and how great, correspondingly, the factor of ‘calculation’ – and how great, conversely, was the sense of moral duty; how great, indeed, was Adenauer’s appreciation of Judaism and the Jews and, consequently, for Israel?

This may be the most banal of all characterisations of the great Rhinelander, but it is accurate: Konrad Adenauer was a multi-layered character and is not easy to grasp. A politician who could be a master of discrimination and reticence but also a ruthless champion of the interests he considered to be politically right. Adenauer was a strict moralist and at the same time a man of Rhenish liberality. He was a pious Catholic believer, ‘God-fearing’ in the better sense of the word, and yet never an unquestioning obstinate believer in hierarchical structures. He was able to engage critics and sceptics as well as employing his untrammelled assertiveness. He wanted to ensure that the dark years of National Socialism were behind Germany and to start a new chapter, while remaining sceptical as to how staunchly democratic his fellow countrymen truly were. Consequently, there can be no simple answer to the question of his relation with the Jewish community, and of the effect this relation had on his politics as federal chancellor. Most importantly, there cannot be an answer that leaves out his attitude to the Jewish community during the years of his ‘first career’ as a local politician[7] in Cologne.

Not without reason, and certainly not primarily through calculation, Konrad Adenauer revisited his own experiences – especially those of the Weimar Republic years – during his encounters with David Ben-Gurion, and also with innumerable other representatives of Israel or of Jewish organisations. Among the Jews all over the world, too, respect for Konrad Adenauer is fed not least by his rejection of Nazi ideology, never doubted in the post-war years, not even by bitter opponents of his ‘policy of reconciliation’, and by the sympathetic attitude to Judaism and Jewish life in Germany he openly displayed on many occasions.

Towards the end of the 1920s the Nazis first began their embittered campaign of character assassination against the Zentrum (Catholic Centre Party) politician from Cologne. During the charged polarisation of the final phase of the Weimar Republic, he increasingly became the ‘great hate figure of all the radicals in Cologne’[8], as Hans-Peter Schwarz, Adenauer’s biographer, put it. At the centre of Nazi agitation against him was not only the specially ‘reheated’ accusation that Adenauer was a ‘separatist’[9] and supported the secession of the Rhineland from the German Reich, an accusation refuted without exception by all his biographers, but very soon also his positive attitude to the Jewish community, which he had never hidden.

Even before his appointment as Lord Mayor of Cologne, and until the day of his dismissal, Adenauer had always been in close contact with representatives of the Jewish communities but also with Jews in all walks of life: in academia, in the economy, and in the cultural sector. Some were particularly prominent and became defining companions for the talented local politician, informing his career.

A special relationship linked him to one of the most dazzling personalities of Jewish descent in Cologne during the days of the Weimar Republic, the banker Louis Hagen, a convert to Catholicism and heir and chairman of the board of the bank A. Levy & Co. Hagen was one of the most important industrial financiers of the Rhineland – indeed, of the entire Weimar Republic – by far. From 1924 onwards he was co-owner of Deutsche Bank and from 1915 until his death in 1932 president of the Chamber of Commerce in Cologne. Konrad Adenauer was, according to Hans-Peter Schwarz, among those indebted to Louis Hagen, as the latter had supported the career of the political ‘rising star’ without humiliating him.

Louis Hagen played a decisive part in Konrad Adenauer’s rise to the position as Lord Mayor of Cologne. It was Hagen who played the part of ‘kingmaker’ and determinedly supported the young local politician with the Liberals, the faction of the city’s parliament of which he was a member. Together with another influential Jewish politician of the Liberal faction, Bernhard Falk, who also respected Adenauer greatly and was on friendly terms with him, he succeeded in dispelling reservations held by the Liberal faction against the Zentrum party in general and, by extension, against Konrad Adenauer as well.

‘The years that followed’, Hans-Peter Schwarz writes about the friendship with Louis Hagen, ‘are characterised by a close alliance between the older and the younger man. They might be at loggerheads on occasion, but the two respect and appreciate one another.’[10] Konrad Adenauer certainly was a welcome and frequent guest at the entrepreneur’s ‘country house’ Schloss Birlinghoven near Bonn. Soon after taking office, Konrad Adenauer signed the guest book of the manor house as newly elected Lord Mayor. In 1919, Louis Hagen, who had already converted to Catholicism in 1886, even became Adenauer’s fellow party member: He left the Liberal faction in order to join the Zentrum faction of the city’s assembly of deputies.

Just how closely connected Konrad Adenauer felt to the banker became clear once more after the latter’s death in 1932. On 30 September, the president of the Chamber of Commerce had the honour of inaugurating the new Chamber of Commerce and Cologne stock exchange. On the evening of this eventful day, he suffered a stroke and died on 1 October. It was his friend Konrad Adenauer who gave the eulogy in his honour on 4 October.

Louis Hagen’s successor as president of the Chamber was another of Adenauer’s close companions, his friend Paul Silverberg. With Hagen and Falk, he made up the trio of men of Jewish descent who esteemed, encouraged, and supported Adenauer.

Paul Silverberg came from a traditional Jewish family but converted to the Protestant faith in 1895. A lawyer, he probably first met Adenauer during their years as trainee lawyers but certainly no later than 1903 when they were both lawyers and colleagues at the Higher Regional Court in Cologne.

Silverberg, who joined his father’s mining company, played a crucial part in the foundation of the mining giant RAG, which exists to this day and was the firm’s chairman for a long time. He earned himself the reputation of being the ‘lord of lignite’.[11] In fact, he was not only the leading figure of the Rhenish lignite district but also one of the most influential entrepreneurs of the Weimar Republic in general. He was involved in the reorganisation of the Stinnes Group as well as that of Hapag and Lloyd. He was an adviser to the Reichsbahn (national railways) as well as Deutsche Bank.

Politics, too, relied on his advice. Besides Konrad Adenauer, who was in close contact with him, this included above all the Reich Chancellor Heinrich Brüning, who even intended to appoint him minister for traffic and transport in 1931, but failed in this endeavour as a result of Silverberg’s ambitious conditions.

In the Weimar Republic’s declining years, Paul Silverberg moved closer to the right wing of the political spectrum. He made a financial donation to the Nazi party NSDAP via Gregor Strasser, with the aim of encouraging the party to be more pro-business. However, Paul Silverberg was never among the numerous advocates of having the Nazis participate in government during the time before the transfer of power to Hitler, a fact that clearly contradicts the stereotype nurtured above all within left- as well as right-wing circles to this day depicting Silverman as a ‘Jewish supporter’ and follower of Adolf Hitler.

It was probably towards the end of 1933, but at the very latest in early 1934, that Silverberg emigrated to Lugano in Switzerland. In 1936, he became a citizen of the principality of Liechtenstein, where he survived the war. Konrad Adenauer’s association with Paul Silverberg was so close that after the war he urged him to return to lead RAG once again. Silverberg declined but was awarded many honours by his home city of Cologne. On the occasion of his 75th birthday in 1951, he was appointed honorary president of the Cologne Chamber of Industry and Commerce as well as the Federation of German Industries. He remained in close contact with Konrad Adenauer in the post-war years, documented in their extensive correspondence.[12]

Of particular significance, however, was Konrad Adenauer’s cordial relationship with Dannie N. Heineman, demonstrated by their many personal encounters as well as the intensive correspondence between the two men which discussed – especially during the Third Reich – the politician’s more personal issues.[13] Heineman’s was the name that would be mentioned most frequently later whenever Adenauer’s connections with Jews were discussed. Konrad Adenauer was introduced to the ‘driven technician’[14], as Hans-Peter Schwarz calls him, in 1907. This acquaintance would develop into one of the closest friendships Adenauer maintained over the course of his long life, ending only with Heineman’s death in 1962.

Dannie Heineman was born in the United States as the son of German immigrants. After his father’s early death, his mother returned to Germany with the boy. Heineman graduated in electrical engineering and was subsequently employed by the Union Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft, that would merge with AEG later. Leaving AEG in 1905, he joined the Société Financière de Transports et d’Entreprises Industrielles, initially as one of three employees. By the time he retired as its president, the investment company had 40,000 employees.

Hans-Peter Schwarz refers to contemporaries of Heineman’s who regarded the lively, headstrong, imaginative finance executive as a highly educated man ‘with a multi-faceted character, a thoroughly developed social interest, and a passion for art’[15], but also as someone it was better not to cross[16]: ‘When dealing with bankers, whom his technically trained mind regarded more or less as ne’er-do-wells, he was a sadist.’[17] With great single-mindedness, he became an influential ‘Macher’ (doer)[18] and visionary in local public transport as well as long-distance rail transport, chemical industry, and the construction of power stations.

Heineman, who maintained a critical view of politicians throughout his life, thoroughly agreed with the sentiment that ‘industry is constructive, while politics causes disorder’[19]. The fact that he established a particularly close relationship with Konrad Adenauer may have been due to the latter’s soon proving himself a rather unconventional and unusually hands-on politician.

Adenauer would soon benefit from the energetic entrepreneur’s network. Heineman was acquainted with everyone who was anyone, from King Leopold III of Belgium through the politician Walther Rathenau to the composer Richard Strauss, the poet Gerhart Hauptmann, and the painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, to name but a few. Heineman’s illustrious circle of acquaintances included the Zionist Chaim Weizmann, whom he met in 1936. Thanks to his excellent connections with European governments, Heineman was able to persuade the government of Luxembourg in 1939 to allow around 100 Jewish family into the country from Germany. To this request, Heineman added the promise that he would personally ensure the maintenance of the refugees. After German troops entered Belgium in 1940, he had to flee as well, settling in the United States. As a patron of the Weizmann Institute, he was able to support Konrad Adenauer in establishing German–Israeli scientific cooperation after the war.

Adenauer and Zionism – A ‘Rhenish Catholic Zionist’?

One might of course take the view that the widely known connections Adenauer maintained with these leading personalities do not allow a comprehensive perspective of his relationship with the Jewish community and Jewish life in general. This is correct in that all four of them saw themselves as members of the elite of the city of Cologne rather than defining themselves by their Jewish roots. While the Weimar Republic, as the biographies of these men illustrate, represented the heyday of the assimilation of the German Jews, it was simultaneously a period of advancing antisemitism. And at the time when Nazism was gaining influence, a certain degree of courage was required to profess friendship with people such as these, who were still Jews above all in their opponents’ perception. Even more fascinating, however, were Adenauer’s connections with the Jewish community that went beyond the personal level, and in particular the fact that he soon developed an interest in the Zionist movement, which found many sympathisers among non-Jewish public figures of the Weimar Republic.

Adenauer himself located the origins of this sympathy with Zionism as early as in his adolescence. After his return from Israel in 1966, he looked back on this time: The Zionist movement had held a lively fascination for him ever since he was in the sixth form: ‘This was why I passed my Hebrew qualification and taught myself Yiddish in order to be able to read the sources. […] All my life I have had close ties to the older generation of Zionist leaders.’[20] He even mentioned to a journalist that he learnt some Ivrit (Modern Hebrew) during his time at secondary school; however, this may well have been a projection. At the time when Adenauer passed his Abitur (school leavers’ certificate for higher education), the father of the modernised version of the Hebrew language, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, had only just started work on his comprehensive dictionary. When Adenauer was presented with a valuable Bible after the successful conclusion of the Restitution Agreement in 1952, he spontaneously recited the initial verses of a psalm in Hebrew.

The secondary school (the ‘Gymnasium’) did in fact play a key part. Like Konrad Adenauer, the aforementioned Bernhard Falk attended the Apostelgymnasium (the most prestigious school in Cologne) and impressively describes in retrospect how much he was influenced by the spirit of community that united Jewish and Christian pupils at the school: Throughout his entire life, he encountered ‘this kind of genuine and earnest tolerance for those of a different faith’[21] only there. This also had an impact on the world view of Adenauer, who already had the opportunity of openly discussing the Jewish faith with his fellow pupils during his own time at school.

The Zionist movement was particularly active in Cologne and one of the leading sections in the entire German Reich, not least thanks to the universally respected local industrial lawyer Max Bodenheimer. The chairman of the Zionist Federation of Germany, Kurt Blumenfeld, wrote to Konrad Adenauer in November 1926 suggesting that he might wish to join the Zionist movement.[22]

In 1927, Adenauer did indeed join the German committee ‘Pro Palästina’, soon becoming chairman of the festival committee of the association, which numbered among its members men with such resounding names as theologian Martin Buber as well as, in its steering committee, the great rabbi Leo Baeck. The Catholic priest and long-term leader of the Zentrum party, Ludwig Kaas, together with the former Chancellor Joseph Wirth, another Zentrum politician, had previously recommended him as a committee member, prompting Blumenfeld’s request to the Lord Mayor. ‘Furthermore, I plead guilty, with my heart beating faster, to having myself provided the suggestion to ask you to join’,[23] the clergyman confessed slightly sheepishly in response to Adenauer’s inquiry.

Hans Peter Mensing, editor of the Adenauer-Papers, has pointed out that this engagement on behalf of the Zionist movement and commitment to the work of the committee were by no means a matter of course, citing as evidence violence against Jews that took place in Cologne long before the transfer of power to Hitler.[24] In March 1927, the polling station of the Jewish community was attacked; several Jewish inhabitants of Cologne were injured.

On the occasion of a committee conference in Cologne in the same year, on 22 November, Konrad Adenauer – by now a member of the Association – wrote a long and detailed letter to its president Johann Heinrich Graf von Bernstorff, a leading figure of the Zionist movement and member of the Reichstag (Parliament) representing the liberal Deutsche Demokratische Partei. A letter of some interest, too, with regard to his future political line concerning Israel, as it reveals the detail in which Adenauer reflected on Jewish life in the ‘Holy Land’. ‘I hope that the world’s sympathies and the Jews’ own willingness to make sacrifices will ensure the resurrection of the country, like the resurrection of the ancient Hebrew language that preceded it.’[25]

However, Adenauer would not have been Adenauer if he had not used the opportunity to address a carefully wrapped admonition to the Zionist movement. In it, he ultimately followed the reading of the Balfour Declaration[26] with which the British Government gave its ‘agreement’ to the establishment of ‘a national home for the Jewish people’[27] in Palestine which explicitly must not limit the rights of non-Jewish population groups: Zionist endeavours in the historic place, Adenauer pointed out, were ‘a labour of peace, achieved without curtailing the rights of other faiths to whom Palestine is also a holy land, and certainly without curtailing the economic and political position of the non-Jewish population of Palestine’.[28] A barely concealed hint that he – like his proponent in the committee, Prelate Kaas – was not considering the establishment of a Jewish state but initially a home for the Jewish people.

In addition, the Lord Mayor of Cologne adorned his letter to the president with a remark positively oozing local patriotic pride, namely that Cologne was one of the cities in which Zionism was first conceived: Among those buried in the Jewish cemetery in Cologne-Deutz was Moses Heß, one of the spiritual fathers of Zionism, who in his work Rome and Jerusalem[29]gave impulses for the search for a national home for the Jews in the Holy Land.

The last lines of this memorable letter by Adenauer, which could even be read as alluding to the Jewish concept of ‘Tikkun Olam’, or ‘healing the world’, might almost have been penned by David Ben-Gurion: ‘We understand that Jerusalem and Palestine are linked to Jewish aspirations that will be significant not only for the Jewish world. It is our wish that the Jewish farmers and workers attached to the land should organise their lives in such a way that they will be a force for peaceful progress in the Orient and contribute to the cultural advancement of those lands.’[30]

In this context, Hans Peter Mensing, an authority on Adenauer, presents an interesting conjecture. Even though the ultimate proof is lacking, Mensing believes that a plea for Zionism such as Adenauer’s letter to Graf von Bernstorff would have attracted international attention and that it should be assumed that a document of this kind would have sharpened the image the Jews had of Konrad Adenauer even before his time as the first federal chancellor.[31] This might very probably apply to David Ben-Gurion as well, who visited Germany a number of times during these years before the transfer of power to Hitler, in particular in 1930 in order to attend the International Conference of the ‘Liga für das arbeitende Eretz Israel’ (League for a Working Eretz Israel) in Berlin.

Mensing discovers cogent evidence in the words Ben-Gurion found in conversation with the chancellor of the grand coalition, Kurt Georg Kiesinger, on the occasion of the memorial ceremony after Adenauer’s death, in which he emphasised that ‘Adenauer’s contribution to the material development and the moral support of his nation’[32] could not be overestimated: ‘Even before he encountered him in person, he regarded Adenauer as an extraordinary personality.’[33] Mensing considers it conceivable that this appreciation was based on early information of the Weimar years, and that Ben-Gurion had not come across Adenauer’s name for the first time after the war.[34]

Considering his profound interest, one might in fact maintain the outlandish idea that during these years, Adenauer was something of a ‘Rhenish Catholic Zionist’, deliberately establishing a relation between his own religious consciousness and the Jewish faith. In this he would not have been alone. Dedicated Catholics in particular – such as the Catholic Prelate Kaas, who had enlisted him for the Palestinian cause – displayed, besides a few instances of antisemitic attitudes, notable sympathy for the Zionist movement. While antisemites welcomed Zionism as a way of ‘elegantly’ getting rid of the Jews, the goodwill in Adenauer’s circle was based on genuine interest.

Looking more closely we can discern, provocatively speaking, two tendencies within Catholicism where the relation with Judaism and the Jews was concerned: The one might perhaps be called ‘Good Friday Catholicism’, which blamed the Jews for crucifying Jesus and, in the person of Judas, having betrayed him and delivered him into the hands of his pursuers. This anti-Jewish attitude becomes painfully obvious in the history of the problematic Good Friday Prayer, which has its roots in the sixth century and prayed for the return of the ‘faithless’ Jews, remaining a fixed part of the liturgy for many centuries.

On the other side we find the ‘Easter Vigil Catholics’. The Easter Vigil, during which the central Jewish narratives of the Bible are recited in up to six readings from the Old Testament and in which the resurrection of Jesus and his being confirmed as the awaited Messiah are documented in merely two readings from the New Testament, liturgical tradition – admittedly, this only applies after the Second Vatican Council and was not already the case during Adenauer’s time in Cologne – emphasises that Christianity is unimaginable without the Jewish identity of Jesus Christ; indeed, that a church acting in anti-Jewish ways is a contradiction in itself. The Catholic Christian Konrad Adenauer and several of his fellow party members in the Zentrum undeniably represented the second tendency.

Indeed, in Adenauer’s case this obvious sympathy with Judaism cannot even be played off against his denominational Catholic character, as it was on an entirely separate level. This is demonstrated by another minor episode highlighted by Jürgen Court in an article on Adenauer’s university policy. As the University of Cologne was managed by the local authority at the time, the Lord Mayor as head of the board of trustees of the university was able to exert considerable influence on the appointment of professors. As a politician with a keen awareness of the importance of power, Adenauer of course knew to make use of this. In 1930, the Kölnische Volkszeitung, a newspaper usually close to the Zentrum, accused Konrad Adenauer of being a deciding factor in Cologne University preferring Jewish professors over Catholic ones. This accusation was preceded by Adenauer’s having strongly advocated the appointment at Cologne of the expert in Romance languages Leo Spitzer, who was of Jewish descent.

The scholar Emil Gamillscheg, who had lost out to Spitzer in another appointment procedure and was ironically appointed as a reviewer in this procedure for Cologne University, wrote to Adenauer in November 1927 appealing to his ‘denominational conscience’ with an explicit request to prefer the Catholic candidate Emil Winkler: ‘The two candidates included in the proposal together with Winkler, the Marburg full professor Leo Spitzer and the Munich adjunct professor Eugen Lerch, are both baptised Jews, and for that reason alone I do not believe that this choice is a particularly beneficial one for the Catholic University of Cologne.’[35] Quite apart from the fact that Lerch was demonstrably not of Jewish descent at all, the attempt at playing off Jewish against Catholic background was as antisemitic as it was perfidious. Furthermore, Gamillscheg’s attempt was pointless, as Konrad Adenauer had repeatedly and demonstratively taken the side of the Jewish citizens.

Finally, on 28 April 1930, Adenauer prevailed. ‘His’ candidate Leo Spitzer was called to Cologne University. Of course, it turned out to be a brief episode and Spitzer’s employment ended when he was dismissed by the Nazis in 1933. Later, Spitzer emigrated to the United States where he became a professor at Johns Hopkins University. It must be said that Adenauer’s efforts on behalf of Spitzer, which went right up to the limit of the ‘political influence’ admissible in an appointment procedure of this kind, were not primarily due to the latter’s Jewish origin but because Adenauer was convinced that due to his qualification, he was the right man for the position.

All the same and as was to be expected, Adenauer’s advocacy on behalf of a scholar of Jewish origin in this instance became the subject of Nazi attacks. A contributing factor was that as early as 1925, Konrad Adenauer had made more than a little effort to prevent the eminent but not uncontroversial historian Karl Alexander von Müller being appointed to Cologne University. During the Weimar years, von Müller showed himself to be a bitter enemy of the democratic system, and after the transfer of power he played a significant part in Nazi ‘Judenforschung’ (study of the ‘Jewish Question’), proving that he was no mere ‘blind follower’.

Adenauer, the Catholic Christian, had shown the same attitude in the early 1920s, looking beyond denomination and not wanting to expose the Jewish citizens of Cologne to discrimination, proving himself a Lord Mayor with no fear of spiritual topics and not shying away from conflict with the powerful archbishop of Cologne, in those years Karl Joseph Cardinal Schulte. In a letter to the spiritual leader in July 1922, Adenauer rejected the bishop’s criticism of subsidies granted for a crematorium: ‘I never could and still cannot understand on what basis a Catholic should claim the right to prevent a Protestant or a Jew from choosing a form of burial he considers correct.’[36]

A further impressive example is found in a book by Zvi Asaria on the Jews in Cologne, recounted on the occasion of the reconstruction of Roonstraße Synagogue in 1959, the very synagogue desecrated by neo-Nazis immediately after its inauguration: The author mentions a school building on Lützowstraße in Cologne that had been erected as a Jewish school before the First World War but was then used as a military hospital. Asaria writes: ‘The tendency emerged within the communal committees of housing a business school in the new building, rather than the Jewish school. Headmaster Coblenz together with the community rabbi Dr Frank successfully resisted these intentions. The decisive word was spoken by Lord Mayor Dr Adenauer: The school building would fulfil its original purpose.’[37]

Within his communal government, too, Konrad Adenauer supported staff of Jewish origin. Besides the Stadtdirektorin (head of the city’s administration executive) Hertha Kraus, the Cologne ‘finance minister’, the Stadtdirektor and financial director Dr Albert Kramer played an important part, working with the Lord Mayor from 1920 to 1933, i.e. during almost his entire time in office.

Because of his Jewish origin, Albert Kramer was retired on 1 May 1933. Afterwards he worked for the Cologne Synagogue community and for Zionist associations. Above all he became known among the Jewish citizens of Cologne in these difficult times as a ‘foreign exchange adviser’ to Jewish emigrants and consequently as an indispensable ally to those wanting to emigrate. Tragically, his own emigration did not succeed. On 30 October 1941, he and his wife Irma were deported on the second deportation train from Cologne to Litzmannstadt/Łódź Ghetto, where he died only a year afterwards. The cause of death given was ‘Herzschwäche’ (cardiac insufficiency), whatever that might have meant at the time. His wife Irma was transferred from Litzmannstadt to Auschwitz in 1944, where she was murdered in August of that year. In 2016, a ‘Stolperstein’ (lit. ‘stumbling stone’, small brass square bearing the life dates of murdered or persecuted Jews and other victims of the Nazis, set into the pavement outside the victim’s last voluntarily chosen abode) was set in the pavement outside the couple’s former home in the Paulistraße in the presence of Lord Mayor Henriette Reker, commemorating the life of Albert Kramer.

Overall, Adenauer’s contribution to the harmonious coexistence of Jews and Christians in Cologne was a considerable one, as demonstrated by the speech given by the chairman of the association of former Cologne Jews with whom Adenauer met during his journey to Israel in 1966: ‘We have a most positive memory of the years of your activity in Cologne, during which you as Lord Mayor of the city always demonstrated sincere understanding for the interests of the Jewish citizens. During this period, we and our non-Jewish fellow citizens of Cologne lived and worked together and for one another […], taking part in the public life of the city, until the rule of terror abruptly tore apart all these connections, putting a sudden end to the venerable Jewish community in Cologne.’[38]

Adenauer the ‘Blutjude’ – Nazi Defamation

With Adenauer’s overall openly displayed sympathy with the Zionist movement and with the Jewish community in general, it was not long before Nazi hate propaganda began to appear. Many of the particularly fiercely antisemitic members of the Nazi party were firmly convinced that Adenauer himself was ‘of Jewish blood’ and aimed their hatred specifically in this propagandistic direction.

The inflammatory pamphlet ‘Juden sehen dich an’ (lit. ‘Jews are looking at you’), particularly heinous even in the context of the time, presented Konrad Adenauer under the heading ‘Blutjuden’ (lit. ‘Jews by blood’) in a ‘picture gallery’ accompanied by captions inciting to hatred – together with Karl Marx, Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Kurt Rosenfeld, Matthias Erzberger, and many others. Konrad Adenauer was the last in the series, with the caption ‘The Lord Mayor of Cologne, ruined Cologne through wastefulness etc.’[39] The pamphlet distinguished between ‘blood Jews’, ‘lying Jews’, ‘fraudster Jews’, ‘subversive Jews’, ‘artist Jews’, and ‘money Jews’. Adenauer was included in the categories of ‘blood Jew’ as well as ‘subversive Jew’.[40]

The publication was produced by a particularly confirmed antisemite: Johann von Leers, ‘official biographer’ of Hitler, who rose to becoming one of Joseph Goebbels’ closest assistants in the NSDAP leadership and subsequently, after the transfer of power, to being a historian and – without the required qualifications – a tenured professor at Jena University. He was an inveterate and fanatical antisemite who would continue to play a part in the story of Israel and Adenauer even after the war: Having first fled to Argentina, he then moved on to Egypt where he converted to Islam, working closely with the mufti of Jerusalem, Muhammad Amin al-Husayni, who had previously been received by Hitler, and working against the alignment with the West and for an ‘Arab revolution’ against the Zionists. It was here that he wrote to the American fascist Keith Thompson in 1958, referring to those Nazis who had by then found refuge in Arab countries: ‘Let Adenauer rant that honest German patriots are not turned over to him or his British and American bosses by liberty-loving Arab countries.’[41]

The title page of the hatemongering Nazi newspaper Westdeutscher Beobachter