Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

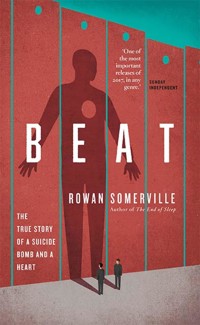

In the midst of the Second Intifada, two acts of extreme violence lead to an act of extraordinary humanity. A suicide bomb was detonated outside a nightclub in Tel Aviv, killing twenty-two people, mostly young Israelis. The next day, in an apparently retributive act of violence, an Israeli settler shot Palestinian pharmacist, Mazan Al-Joulani in the neck, rendering him brain-dead. From the ashes of these deadly events rose an incredible act of generosity when the family of Al-Joulani agreed to donate his heart to a dying Israeli. The son of pioneering cardiologists, Rowan Somerville travelled to the Levant to speak with survivors and their families, interviewing the surgeon who performed the transplant, and meeting the family of the suicide bomber Saeed Hotari. In this close look at humanity at work, Somerville's writing is at once personal and objective, an outsider's unbiased view of events steeped in, but overcoming, prejudice. The close observations and fastpaced narrative style have the immediacy of a contemporary thriller.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 400

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BEAT

the true story of a suicide bomb and a heart

ROWAN SOMERVILLE

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

Dedication and epigraph

To the healers of the world, the doctors and the peacemakers: in particular, you, Professor Georges Audry, and the beautiful operation you carried out on 13 October 2011.

—

Of course two peoples and two languages will never be able to communicate with each other so intimately as two individuals who belong to the same nation and speak the same language. But that is no reason to forgo the effort at communication. Within nations there are also barriers, which stand in the way of complete communication and complete mutual understanding, barriers of culture, education, talent, individuality. It might be asserted that every human being on earth can fundamentally hold a dialogue with every other human being, and it might also be asserted there are no two persons in the world between whom genuine, whole, intimate understanding is possible – the one statement is as true as the other. It is Yin and Yang, day and night; both are right and at times we have to be reminded of both.

Herman Hesse, The Glass Bead Game (1943)

Prologue

A small hand pulls at the refrigerator, the seals around the door resist and then give with a familiar sucking sound. Light, so yellow in the early morning, floods the shelves. An eager little face peers up at the treasures. There’s orange juice, and milk, wine in a half-corked bottle, a plastic tray with a wilting lettuce and the flash of colour from a forgotten tomato. There’s part of a roast chicken, a pat of butter repackaged in its crumpled wrapper and sausages straining against a roll of greaseproof paper. Below are cheeses and a chocolate mousse.

Defrosting on the top shelf is a fist-sized mass of dark tissue, purple-red, mottled with spots of clotted-cream fat. As it collapses, its cling-film covering sloughs off like the skin of an old snake.

The boy hardly gives it a glance. It’s a heart, he knows this, like the one in his own chest. Not alive, but no less human.

PART I: Blood

ONE

1 June 2001

It’s the first night of June 2001. A crowd of people are gathering, mostly young women, the oldest twenty-three. They are queuing outside a nightclub, milling about, breaking ranks to greet, shriek and hug. There is much admiring of outfits, talk of hair, of exams and shoes and the coming holidays. Groups of teenagers flock from one cluster to the next like birds breaking from one tree to another. There are comments on other groups, on looks, recent histories and loves.

The sea is no more than fifty metres away, rising and falling like the chest of a sleeping giant, heaving and subsiding against the concrete of the sea wall. A single-storey building of exposed concrete stands between the crowd and the water, which follows the coast in a gentle S. Two lamp posts cast light over the car park, over the gathering crowd of young people. The lamp posts were painted blue last week, a shade of blue just lighter than evening sky. Peals of laughter explode in the warm night like muted fireworks, mingling with the whining screech of scooters and clacking of an old Mercedes taxi unloading a couple of smartly dressed girls.

There are boys, too; teenagers and a few young men in their early twenties, mooching around, pretending not to look, waiting in the queue, chatting, wanting to blend in, fidgeting to be noticed but affecting disdain, greeting friends with hugs and handshakes. Some are hoping their new jeans look good, or touching the faint dark clouds of recent facial hair, the scars of pimples. They are hoping for a dance, for a kiss or something more.

It’s a Friday night, the beginning of a holiday. Girls will be allowed in for free before midnight on this particular Friday, but the doors are still closed. It’s after eleven o’clock, and there are more than a hundred and fifty young people outside, but for some reason the doors are closed. They should be flung wide by now, but they are not; they won’t be until the security guard cracks open the gate and steps out.

His name is Jan Blum. He’s just checked the fire exits and is now heading to the car park to look around. A Ukrainian, Jan was living in Kiev with his wife Irena and their two-year-old daughter only six months ago. Now he has a new life, a new country, and a new language. He’d never dreamed of becoming a doorman in a nightclub, but it’s regular money with friendly people and a good atmosphere. He likes it. He goes to work contented and comes home tired.

Jan is twenty-five, a solid young man with thick forearms, short cropped hair on a somewhat rotund head and features that seem concentrated in the middle of his face. His eyes are close together and deep-set, giving an impression of seriousness. This should be a useful trait for a club doorman, but here at the Dolphi there’s very little trouble, especially tonight: a disco for teenagers for International Children’s Day. Jan’s job is more to protect the young people than to police them. They’re nice kids, friendly, almost all from Russia and former Soviet states. They, like him, are grateful for their lives here.

This afternoon he picked up his daughter from kindergarten and settled down for a nap with Irena. Tomorrow their first proper holiday will begin, and they would fly back to Kiev to see the rest of their family.

An hour after falling asleep, Jan woke, heavy with the dreams of a hot summer afternoon. From the comfort of a bed shared with his wife and baby daughter he wondered aloud whether to miss his final shift. Should he go, shouldn’t he … Then he remembered that his cousin Sergei would be bartending that night, which decided it. He resolved to do his final shift and then enjoy his holiday.

—

The two girls who climb out of the Mercedes taxi are sisters, Lena and Julia. They wait in the queue, one in jodhpurs, the other in tight trousers. Julia has her hair in braids, secured with tiny white rubber bands, and her sister has green polish on her fingernails, a colour that upset her mother but promises to glow thrillingly under the ultraviolet light of the nightclub. The girls are chatting, about their exams, music, their little brother Sasha, the dream Lena had the night before.

Lena, an artistic girl with her sights set on going to university, was woken by a haunting image. She was standing in a white bridal gown. On her finger was an embossed gold ring. But next to her, where a groom should have been, there was nothing.

Julia, two years younger, doesn’t care about dreams. Her interests are trance music and her ever-expanding menagerie of fluffy toys. Furthermore, their grandmother – an expert on all superstitious matters, like many Soviet women of her generation – had told them not to worry. A white dress could only be a positive sign.

—

A few hundred metres away Uri approaches. He has no intention of going to the Dolphinarium, but his car is parked in the car park and he’s strolling along the seafront after a busy shift at work. Uri is thirty-two and a social worker, or a ‘house father’ at the community centre. Unmarried, good with children, he is a man with a kind face and thick dark eyebrows that seem to struggle to avoid each other over his nose. Uri is one of those men with a particularly square jaw, like a cartoon hero. It juts out when he smiles, revealing a gap between his front teeth.

Hoots of laughter and the shouts of young people reach him well before he arrives at the crowded area in front of the club. Social life – meeting friends, having fun, ignoring yesterday and acting as if tomorrow were not on the agenda – is a culture in and of itself in this city, even amongst recent immigrants such as these. Nightlife connoisseurs the world over have commentated on the extraordinary commitment to partying in this warm Mediterranean city. No matter the night of the week, the streets teem with activity, the bars are packed. It’s as if the very act of socializing, of drinking and laughing, of dancing with abandon, is, if not actually sponsored, at least condoned by the municipality. It’s a young place in a young country.

—

Mariana has come to the Dolphi to let off a little steam after weeks of intensive studying for her matriculation exams. She looks gorgeous as she waits in the queue, standing with her friend Anya. Mariana has long reddish hair, a bountiful, usually smiling mouth and wide, perfectly almond-shaped eyes. Until this night, few people have seen Mariana wear anything but shorts or trousers – usually jeans – but tonight she’s wearing a miniskirt. She looks radiant.

An hour earlier, Mariana quarrelled with her father. She had promised her little sister Sophia that she could come with her to the nightclub, but as they were getting ready their father rose from the couch like an imperious genie and forbade it. Fourteen was too young for a nightclub, he’d insisted. Usually Mariana was able to cajole him a little, convince him that things worked differently in this country, change his mind, but not tonight. He wouldn’t budge; he refused to even discuss it. Mariana tried explaining that it was completely safe – tonight was a night for teenagers, teenagers like them, from Kiev and Irkutsk, from Moscow and St Petersburg. Everyone would know each other. But her father wouldn’t hear of it. She’s put the disagreement out of her mind, though, as she stands in the queue with Anya, chatting and laughing. They make plans to get up as early as possible the following morning and spend the day on the beach.

—

Polina is standing directly behind the two girls. She’s wondering why the club doors are still closed. They’re normally open by a quarter past eleven at the latest. She wonders if it’s a deliberate delaying tactic so that the girls who should be allowed in for free before midnight will have to pay.

Such thoughts disappear upon catching sight of the mass of blonde hair and unmistakable face of Anya right in front of her. Polina has known Anya since nursery school in eastern Russia. They’d been learning to talk when they first met; they’d even shared a potty in the local kindergarten. And now they are here, standing next to each other thousands of miles away, wearing make-up, waiting outside a nightclub in a warm country, thinking about boys. They scream with delight. They hug and exchange summaries of their young lives, their chatter bursting into the blue night like flocks of starlings. The crowd surges, and they are separated. Anya is astounded by how beautiful Polina looks, like a movie star or a model.

Dozens of young people are arriving by taxi, by scooter, and on foot from the bus station nearby, everyone edging towards the entrance of the Dolphinarium, coming together, drawing in, like iron filings towards a magnetic pole. Above them all the building’s totem, a copper dolphin, sits atop a concrete plinth gazing out to sea.

—

Jan Blum comes back to the club doors and chats with his cousin Sergei. It will be a long, hot night, and busy too, judging by the crowd outside. Jan checks his messages. It’s his boss. What are you doing?

Out in the front with Sergei.

Go check the car park.

I’ve done that.

Do it again, there’s hundreds of people around.

Jan shrugs and tells Sergei he’ll see him later. He goes off to look once more around the car park.

—

Diaz and Viktor arrive on Viktor’s scooter. Diaz is one day into his first-ever leave from the army, and he’s spent his afternoon playing one of Vik’s computer games. His life is crazy. One day he’s at work, on patrol with an assault rifle and live ammunition, and the next he’s sitting in his best friend’s room strafing scores of enemy aircraft in a computer game.

Diaz is eager to do something for his new country, to be a part of it by giving back. His mother is still in Moscow and he calls her whenever he can, begging her to come. This is our place, he says to her. But she won’t join him. She’s scared; she has a new baby. This new country makes her nervous, but Diaz feels like he belongs in a way he never felt in the country of his birth. He tells her all this, but he does not tell her how much he misses her – misses her so keenly that it makes him feel wretched every day. He doesn’t tell Viktor either, or even Natalie, his girlfriend.

Only the woman who runs the shop underneath his flat knows how much Diaz misses his ma. She knows just by looking at him. He goes into her shop almost every day, ostensibly to buy something, but more because she’s a woman who knows where he’s come from and what he’s left behind. She is kind and does what she can to bring some comfort into that tense space between being a boy and a man.

Diaz and Viktor had originally planned to go to a different nightclub that evening, but Diaz insisted that they stop off at the Dolphinarium first because his girlfriend Natalie will be there. Natalie is fifteen and gorgeous. He plans to surprise her before she goes in and then to whisk her off to another club that he prefers, Metropolis. Viktor doesn’t want to be at the Dolphinarium; he has a kind of distaste for the place. And anyway, three of them can’t fit on his scooter.

—

A young man with fine features, Saïd, moves towards the thickest part of the crowd. He and Uri Sachar – the social worker – are the only people in the immediate vicinity who have no plans to enter the club. For generations, members of his family have owned land, lived and died within twenty kilometres of this nightclub, but neither Saïd, his brothers, nor his father have ever been as close as he is now. He stands alone in the crowd, wearing a stylish kaftan with wide, loose trousers, a tracksuit top and brand new sneakers. His hair is short and neatly cut, his eyes brown and wide apart, his complexion pale. There’s a fragile, gentle look to him that the faint black line of his moustache does nothing to diminish.

He is tense.

A man approaches him; his name is Eduard. At twenty-two, Eduard is the same age as Saïd. An army boy in a tough regiment, he’s been trained to react to situations that don’t look right. Eduard nods towards the case Saïd is carrying: ‘What’s that?’

Saïd answers. ‘It’s a tarbuki drum. I’m playing tonight. It’s going to be a big one.’ His nervous expression turns into a confident smile. Eduard, relieved, returns the smile and walks off. Amidst all this noise and excitement, this camaraderie, Saïd feels acutely alone. Everything around him shimmers with that vivid clarity people experience in falling or drowning. He is a young man with a newly minted sense of purpose. It is 1 June 2001, twenty or so minutes before midnight, and he stands alone in the heat of the evening. A mass of young people – mostly teenage girls – chat and laugh without a care in the world.

—

Diaz is unaware of Saïd’s presence, indeed of his existence. He is concentrating on re-spiking his hair. Vik told him before they set off that evening that he was wasting not only time but also hair gel, sculpting his hair into spikes that would be flattened by the motorcycle helmet. Diaz didn’t care. He can buy as much hair gel as he wants. He’s earning money as a conscript in the army. Not much, but something. What does concern Diaz is that he cannot find Natalie on his one night’s leave and, at any moment, the club doors will open.

‘Give me your phone,’ he shouts to Viktor.

Viktor doesn’t want to give him his phone. He doesn’t want to be at this nightclub. He can see the traffic getting worse and the crowd outside the club becoming so thick that it’s impossible to make out who anybody is.

‘I’ve hardly got any credit left,’ Viktor replies. ‘Let’s get out of here.’

Diaz insists. He needs to call Natalie.

Viktor tosses him the phone. Diaz catches it, dials, and Natalie answers right away. Success! He walks away, cooing and chatting.

—

Anya is in the crowd – a different Anya – let’s call her the second Anya. She originally decided to stay at home, but then her friend Nadezhda had turned up at her house in tears. She’d been arguing. Who with? Anya had asked. Everyone, Nadezhda had sobbed. Anya knew this meant her mother. Nadezhda wanted to die, she’d announced. Anya had scolded her for saying such a thing, and being a pragmatic sort of girl, she came up with a solution: ‘We will go out,’ she said.

‘We don’t have money,’ Nadezhda told her.

‘We’ll go to the Dolphi, it’s free for us before twelve.’

Anya had almost enough money for a taxi ride there and back, and they soon found a sympathetic driver and pleaded with him to take them for exactly half the money in her pocket; theoretically, they decided, someone will take them back for the other half. The driver dropped them at the corner and waved them off with a smile. Who could refuse two teenage girls all dressed up on a Friday night? Even if they were Russians.

As soon as Nadezhda and Anya arrive outside the club they conclude that they’ve made a good choice: there’s graduation to celebrate and a friend’s birthday too. Pointless to stay home. They’re standing in the crowd chatting away when Anya sees her boyfriend Ilya. Theirs is a proper relationship, not one of those teenage romances. Anya and Ilya are a serious item. They plan to find an apartment as soon as school is finished, and eventually they’ll get married.

But Ilya told her that tonight he was going to another club, called Yellow, and that he wouldn’t be able to get her in. Why was he here? He had specifically not asked her out this weekend, having promised that they’d go out another time. Anya had told him that she’d spend some time with her ma, but then Nadezhda appeared with all her dramas, and so she’d changed her plan. And yet, here was Ilya, wearing a new top and smart dark trousers.

She doesn’t waste time thinking. She walks straight up to him. ‘Why are you here? You’re meant to be at Yellow.’

‘I’ll explain later.’

‘Tell me now.’

‘I told you. I’ll explain later.’ Ilya slouches off, but before Anya has a chance to process what’s going on, he runs back. ‘Just remember, I always loved you and always will.’ He dashes off, his face flushed with emotion. The girls look at each other. Nadezhda laughs and rolls her eyes. ‘It’s a soap-opera night tonight – psycho mums, weird boyfriends, black cats crossing roads – we should never have left the house.’

The edges of the sky are stained nicotine yellow with the glare of the streetlights.

Maybe there is something in the air – something like a full moon, some catalyst for hysteria.

But the moon is not full.

—

Maksim is up near the front of the queue. He’s determined to be the first inside. He is friends with the doorman. Maksim’s been coming to the Dolphi since the beginning and everyone knows him; he’s that kind of person. He’s also one of the few people who knows why the club is opening late tonight: it isn’t a ploy to cheat the girls of free entry – it’s a surprise. There’s a new room opening and the management is making last-minute fixes so everything looks perfect.

Maksim’s best friend Alexei arrives. Normally Alexei’s shy and gentle, but tonight he’s full of energy and … loose. It’s as if he’s taken something, but that isn’t his style. Nonetheless he’s behaving like a completely different person, like someone with nothing to lose.

—

As Anya watches her childhood friend Polina drifting away in the crowd, she remembers that she has no money on her. Not even a single coin in her pocket. She asked her mother for something but her mother had nothing to give. Her ma is so broke that she was obliged to borrow her bus fare from the supervisor of her medical course. Her mother never would have let her come to a club this far away, but Anya hasn’t been entirely honest. She claimed she was going to celebrate the birthday of a friend who lived down the road, which had a grain of truth in it. She will be celebrating her own sixteenth birthday in a few days’ time.

But Anya doesn’t care about money right now. She’s happy to be at the Dolphi, happy to have just seen Polina. There’s no point worrying about pocket change; she knows loads of people, and there are sure to be boys to buy her drinks.

—

Saïd watches another couple of men approach. He fortifies himself with a phrase he’s been taught, make ready your strength to the utmost of your ability, advice from the Almighty Himself. The young men approach and want to know about the drum case. Their accents are thick with the tones of their former Soviet homelands. Saïd explains about the drum. It’s the trend in the early 2000s; dance beats with live drums, a cultural cocktail. They are convinced and they leave, wishing him a fun night.

At some point Saïd smiles, thinking of his family. Not only will they be proud, but their debts will be paid off. He has not spoken to his parents for a month, more; he has hardly been home to the apartment he shares with his brother. Recently, his friends, his new friends, have stayed with him night and day. They’ve talked with him long into each morning. They’ve told him to make a list of seventy people to accompany him into his glittering future, but Saïd Hotari does not know seventy people. He uses people who have been good to him, even if their names are unknown: a fruit-seller who spoke kindly from behind a pyramid of scarlet strawberries, the owner of the café who asks about his family abroad, one of the teachers in technical college, his elder brother, whose tracksuit jacket he is wearing …

—

Anya is listening to Nadezhda whilst keeping an eye out for Ilya. She sees him chatting with a boy called Roman. ‘One of those guys who dates five girls at the same time,’ she says. Anya breaks away from Nadezhda and marches straight up to her boyfriend. She is like that: direct, no nonsense. ‘What did you mean then?’ she demands.

Roman is uncomfortable, but she ignores him. Ilya is brash. ‘I was joking, forget it.’ At that moment, as if buckling under the force of three hundred young people’s yearning, the club doors open. Had it happened later, Anya and Ilya might have had an argument or kissed, but now Ilya is carried away by the current of the crowd, and Anya lets him go. She doesn’t understand what he’s talking about, but he looks so handsome in his clothes, and sometimes that’s enough.

—

Saïd observes the male and female forms move and jostle towards the club doors, all of them in light and flimsy clothes, their pale bodies exposed in a way he never sees at home. One boy is wearing nothing but a pair of bright red shorts and a loose vest, as if he is going to do sports rather than visit a nightclub.

—

Jan Blum is making his way back into the crowd. He needs to be at the front now that the doors are open. There’s nothing going on in the car park – not that there’s much he could see with all the people milling about. As he’s weaving through the masses, he brushes shoulders with Uri Sachar, who’s getting into his car to drive home. They don’t notice each other. Jan is focused on the busy night ahead, and the next two weeks of uninterrupted holiday with his wife and baby daughter.

—

Saïd watches everyone. He taps the shoulder of a girl in front of him and demands her name. His tone is aggressive. The girl feels uncomfortable. She walks away. This rejection makes it easier for him. He needs to be able to hate these people, what they represent, rather than who they really are: daughters of fathers, beloved children of mothers, sisters of brothers, young people putting their tender feet into the world, just like him. He needs to see them as part of the idea that has made his life, and the life of everyone he knows, hopeless. As long as he doesn’t know them, he can do this.

—

The crowd is thick with young people. The doors of the club are open, teenagers funnelling through, young men standing to the side and letting the girls go first so that they can take advantage of the free entry before midnight.

Anya is by the door, for one moment next to Ilya, their arms rubbing against each other, up and down, like boats in a crowded port, sleek young boats ready to sail out to sea. She wants to say something to him, tries to pull him towards her, but he’s borne away by the ebb and flow of the crowd. Diaz is shouting to Vik that he can see Natalie. Maksim is inside the club. Alexei is near the door but stuck behind the fence. Ilya is at the entrance now, stepping aside to let girls in before him. Uri’s car is pulling out of the car park. Julia and Elena are nearing, laughing about their grandmother’s nightly blessing: God be with you, God be with you. All around there is noise: laughing, flirting, the music of longing.

—

There are fourteen minutes left of this day, the first day of June 2001, the seventy-seventh International Children’s Day.

Saïd mumbles prayers over and over; he flicks a switch; he screams the name of God into the night sky. He has a bomb strapped to his chest. There are ball bearings, bolts, copper screws, and bullets. He closes his eyes and becomes a fiery cloud of hate and destruction.

—

Ilya is killed. Diaz is killed. Jan is killed. Julia and her sister are killed. Mariana is killed. Roman is killed. Uri is killed. Anya is killed. Saïd is killed. Twenty-one are dead or dying. Over one hundred are injured.

The cracked concrete runs with blood.

TWO

What Is Anyone?

I knew their names. I knew each one of their names. I knew what they looked like. If they passed me on the street, I’d probably recognize them: Jan, Marina, Roman, Ilya, Anya, Catrin, Alexei, Irena, Yelena, Julia, Raisa, Netanya, Diaz, Simona, Saïd, Liana, Uri, Maria. But they weren’t going to pass me on the street. For the past ten years, they’d been dead. Instead of falling in love, becoming pregnant, raising children, instead of any such things, they were dead. I hadn’t met them, and I’d never meet them. They were memories I didn’t even have.

I’d never been to Israel. Nor had the slightest desire to go. But now, ten years later, because of these people, because of the massacre outside the Dolphinarium nightclub on the first night of June 2001, I was on a plane to Tel Aviv.

It will take four or five hours to get from London to Israel, but as soon as I board the plane at Heathrow I feel like I’m already there. As I queue for my seat, I try not to stare at the men around me with luscious Abrahamic beards and eighteenth-century frock coats, in black suits and crisp white shirts with long silky tassels trailing below their hips. There are young boys with close-shaven hair and curling side-locks. There are women, too. Young, old, svelte, heavy, dark, fair. Some look as if they’ve decided to dress up in not-very-well-thought-out disguises. Skirts and jackets in dull materials and muted colours, clothes distinctive in their lack of distinction. Some wear head scarves, some wigs that look more like wigs than hair; a wig worn to hide hair rather than pretend to be hair.

Hats are everywhere: fedoras, broad brimmed, narrow brimmed, high crowned, indented and sloping every which way. A magnificent homburg bulldozes past me, heavy and deep black. Further down the plane there’s a pair of broad, circular low-crowned hats with brims, as worn by Clint Eastwood in one of those westerns in which everyone dies. There’s all manner of skullcaps – crochet, small, white, satin black, rainbow. The people surrounding me could be anyone from anywhere, but they are all connected by virtue of headwear.

The plane is full. There’s a gentleman already sitting in the seat next to mine. He’s a good-looking man in his mid-sixties, with a meandering slope of silver-white hair as sumptuous as icing on an old-fashioned cake. He’s wearing a smart blue blazer and thick-rimmed glasses of the sort worn by Italian movie stars of the fifties. He seems like someone who takes a few glasses of wine with his lunch.

Before I sit down I open the luggage compartment above my seat. A vanity case is already there, so I push my hold-all on top of it. A youngish man in a double-breasted black frock coat and a particularly wild beard leaps out of his seat. He looks as if someone has thrown a pitchfork of hay at his face. His coat is satin and stretches down to his knees. His pale blue eyes are fierce.

‘You can’t put your bag there,’ he tells me.

‘I’m sorry but there’s nowhere else.’

‘The space – it’s occupied, can’t you see?’

‘There’s plenty of room,’ I say.

‘It’s occupied,’ he says. I look at him, and it’s clear he’s made his mind up. I take my bag off his box and push it under my seat. My seat-mate is smiling, almost laughing.

‘Ah, well, that was a mistake,’ he confides in me, as if we’d been chatting for hours. ‘You don’t want to be putting anything on his shtreimel, my friend. Ha ha, fatal.’ He chuckles and rummages in his breast pocket and produces a folded skullcap, which he smooths onto his magnificent hair.

‘Yes, yes, I know,’ he says as I watch him. ‘I’m not observant. My wife’s family, sure, but not me. One day perhaps …’

He puts his hands over his generous belly. I look at his cream shirt with the faintest pinstripe worn into it. It’s well pressed, soft with age, well cared for, just like him.

‘Ruthie passed six years this March, but her brother and the family, I visit them all. Of course, I’d like to die there, but I’m not ready to do it. I should move, of course I should, but every time I leave, I miss home. Next year in Jerusalem … you know how it is.’

I do not know. I am not Jewish. I do, however, come from an obsessively close family with an all-powerful mother. In addition, my entire childhood was defined by an ancient and patriarchal religious tradition manifest through doctrinaire education and frequent visits to church. Despite the fact that my mother remains atheist and anti-religious, the cultural and dogmatic aspects of my father’s Irish Roman Catholicism were so interwoven with notions of family that my childhood passed without me separating one from the other. Family, truth, love, parents and God were all pretty much one. Good and evil were opposite and absolute. Sunday was for Holy Mass and Sunday lunch. These were two indivisible but separate sacraments: mass a symbolic meal with a symbolic parent (God), and lunch a real meal with real parents – parents who managed to be both physical and symbolic without conflict. Mass left me contented because it was over for another week; lunch left me despondent because it always came to an end. The bad thing about good things, I learned, is that they finish, but that’s also the good thing about bad things.

I’m not suggesting that all – or many – Jewish people will find kinship with me over these influences, but I like to think that some might, if only with the (sometimes challenging) magnificence of my mother. What is certainly true is that from an early stage, I identified with Jewish families: they seemed more like my own than the others I knew, which were smaller, more efficient, modern units. But Jews, like me, came from families – families that lived in the shadows of ancient, invisible forces. It didn’t matter if God was real or imagined: He was the force that shaped my life, my family’s life, and the life of all the Jews I knew. His was the force that ‘through the green fuse drives the flower’. 1

My neighbour leans over to me.

‘You’re Jewish, right?’

‘Not so far,’ I tell him, trying to be smart.

‘Not so far? You’re converting?’

Had my mother been Jewish, I’d be Jewish; but if my father had been a Jew instead of an Irish Roman Catholic, I could be many things, but I would not, by this fact, be Jewish. There’s surprisingly little controversy about the matrilineage of Jewishness, which strikes me as an anomaly. Imagine if Christian, or Muslim, or French, or African-American identity

was only passed through the mother? Nevertheless, so it is with the Jewish people.

Historically, it makes some sense. Matrilineage might be the pragmatic response to two realities. People lie about who they’ve slept with. While almost everyone knows who their mother is, it’s been estimated that 1 person in 25 is not born to the man they think is their father. Thus, matrilineage is one way of confirming that at least one parent is Jewish. And then there’s the sad fact that for the Jewish people, with a history of pogroms and rape, the fact that Jewishness passes through the mother ensures that even a child born of unfortunate circumstances can still be part of the tribe.

Despite ongoing searches for a ‘Jewish gene’ it’s never been found. There have been supposedly Jewish characteristics manifest in DNA, but most of these are thought to be from geographic isolation and are found in non-Jewish people as well. But why should science be the new omnipotent source? It is, in some ways, just another ideology. A rabbi once told me that Jewishness grows in the soul and passes through the mother in utero. The physical world is a reflection of the spiritual world, so the physical connection with the mother mirrors the spiritual connection. Nice, but is it enough?

The fact is, it’s undeniable that the custom of Jewish identity is matrilineal; but it is not an innate truth, as in, say, the heart’s primary function is to pump blood to the brain and body. Without disappearing into Buddhist definitions of relative truths and Karl Popper’s arguments of falsifiability, the heart is a truth on which everyone can agree. Of course, some religiously observant Jews might say that matrilineage is such a truth, but others like me would say it’s a custom – a wise custom – brought about because someone, or a collection of people, decided it would be this way. Now that reliable DNA testing exists, indicating parenthood with practical certainty, perhaps a father being Jewish might also become a legitimate consideration in defining Jewish identity. It’s not impossible: patrilineal descent is already accepted in certain liberal traditions of Judaism.

Citizenship, like matrilineage, is something that is decided, a fluke of birth, the result of a set of causes and conditions that may have nothing to do with you. To be a citizen of the United States of America you need to have US parents, be naturalized, or be born there – or convince authorities that one or more of these is the case. One of my daughters has a fully Italian mother and an Irish-English father, but she was born in New York City so she is now an American citizen. She may choose later to become Irish, English, Italian, or some other nationality. She can convert to Islam, Christianity or Judaism, but as Schlomo Sand, professor of history at Tel Aviv University, points out, within a secular context, she can never become Jewish.

What is anyone? Despite my Irish passport, my Irish father and the sincere Catholicism of my childhood, I was born in London, my accent is English, and my mother is English. When I’m thought of in Ireland (if I’m ever thought of) it’s as English. In England, it’s as Irish. When I think of myself, it’s as both, without friction or contradiction.

As I sit on the plane, possibly the only non-Jew for miles, I look at my neighbour. He is entirely unknown to me and yet he is so familiar, so intrinsically part of the London in which I grew up. My family lived a couple of floors above a famous rabbi and his family. We were three boys and a girl; the Gryns, three girls and a boy. Our mothers had gone to school together and the Gryn son, David, gave me some of the best reggae in my record collection: ska, rocksteady, and it must be admitted, a little dub. Like many people who have the benefit of growing up in a city with a significant population of Jews, I had Jewish friends, Jewish enemies, and – praise be to the paradise I hope Rabbi Gryn is enjoying – Jewish girlfriends. Not that I’m any sort of expert on Jewish people. After all, is someone who’s friends with a few Londoners suddenly an expert on London?

Nevertheless, despite my stated habituation (the fact that, ahem, some of my best friends are Jewish), there’s no getting away from the fact that on this airplane heading to Tel Aviv, I am gazing about like a nineteenth-century anthropologist. Maybe it’s the concentration of so many different cultural manifestations of Jewishness: the Hasidic, the Litvak, the Orthodox, the Conservative, the Reform, the Liberal. Or maybe it’s something else – it seems to me that people on the plane are becoming more Jewish as we get closer to Israel.

In the airport, as people rushed past us, we were the same as any group of strangers anywhere. But as soon as we are on board the plane there’s a noticeable expansion of bustling and chatting, of laughing and commenting, of reaching up and pushing past, of sitting contentedly and watching, or gazing up to the sky, or trying to ignore one’s embarrassing parents … all the different kinds of ways people express themselves, but magnified.

Maybe it is just me, because I have travelled and lived in other places and am so often the odd one out: the only Irishman, the only Englishman, the only European, the only Caucasian. There’s always a deep relief in returning to my own majority. So I wonder – as I look at my neighbour who is smiling to himself with his eyes closed, if it is this – if all the expressions of Jewishness I have experienced so far in my life have actually been hushed up and this Israel I am about to visit is not just a bitterly contested stretch of land in the Middle East but a state of being, where being Jewish can play at its natural amplitude.

Unlike my neighbour who is deeply lost to another, more restful world, I can’t sleep. I fret about how I might find the witnesses from the Dolphinarium that terrible night, find their friends and relations, piece together who they were and what happened. I wonder how I might learn more about Hotari, the suicide bomber, whether I can meet his family and discover who he was and what faith, fury or insanity drove him to annihilate himself and so many others. Since that fateful moment in 2001, the deaths and slaughter have gone on, as they are going on today. Nothing seems to work, neither war-making nor peace-making.

As the plane soars over Greece or thereabouts, and one hour passes into another, I gaze at the young ultra-Orthodox man who insisted I move my bag and wonder what awaits in this tiny patch of land that occupies so much of the world’s consciousness. My neighbour wakes up and catches me staring at the young man.

‘The Haredi may look like a bunch of crackpots who walked off a cheap film set, but they’re increasing in size and popularity whilst every other group is falling apart.’

‘Isn’t most of Israel secular?’ I ask.

‘Sure, half the people don’t believe in God,’ he replies. ‘Until someone gets sick.’ This amuses him for a while. ‘I’m joking of course, some people are as sincerely secular as the Haredi are orthodox, and those people think the rest of us are all mad, but they feel guilty anyway … You do know what a shtreimel is, don’t you?’

‘It’s a hat?’ I venture.

‘A hat? It’s more than a hat, my friend. It’s pretty much the hat.’

I look at him, blank.

‘You didn’t put your bag on the shtreimel itself. It was the box for the shtreimel.’

I ask what the problem was. Was I making it unclean in some way?

‘Unclean? I don’t think so, ha ha, no … not unclean. Crushed is more like it. It’s a very expensive hat, the shtreimel. £3000 for a good one, and most of the Haredi are not well off, so it’s a fortune. He’ll have a good one and a less good one – the rain shtreimel – which is still no change from a thousand quid. But I’ll bet from the way he looked at you that the good one was in the box you covered with your bag. It’s an item, a shtreimel. Real craftsmanship, a lot of animals, twenty or thirty foxes or something, I can’t remember. Ask him to see it. He’d love to show it to you.’

I lean over to my recent adversary, make a joke about our dispute, and ask him if I can see his shtreimel. He looks at me as if I’m insane and raises the palms of his hands as if to say back off.

My neighbour shrugs. ‘Hey, you tried to crush the man’s shtreimel. What’s he meant to do, invite you to dinner?’ He cracks up laughing.

‘A few years ago, there were mass brawls in the streets of Tel Aviv,’ he tells me. ‘Different factions of Haredi battling it out on the corners. The aim was not to injure the others but to capture their hats. There were injuries of course, a broken nose here, a scrape there, but the shtreimels were the important thing. Later they were exchanged like hostages. Cuckoo in the head if you ask me, but better than missiles and bombs.’

I look at the young ultra-Orthodox man, now knowing the full gravity of my offence.

‘They are much misunderstood people,’ my neighbour continues. ‘They feel very strongly about some things. Actually, they feel very strongly about most things: children, prayer, ritual, hats, scripture, their rebbe of course. They see themselves as the only ones living according to authentic Jewish law. The true Jews. They – the ultra-Orthodox – look down on the regular Orthodox, and the Orthodox look down on the Reform, and the Reform think the Orthodox are fundamentalists, and everyone looks down on the secular. It’s like the old joke, you know it? Every Jew has two synagogues: the one he goes to and the one he wouldn’t be seen dead in. Where two or three Jews are gathered there will be a disagreement, it’s the essence of democracy.’

‘So who are the true Jews?’ I ask him.

He shrugs. ‘The ones with a Jewish mother.’

I think of the wiry Jesuit priest from my schooldays who instructed us that only the followers of Christ could enter the Kingdom of Heaven. But only the true followers of Christ: Roman Catholics, not Anglicans, not Calvinists, Episcopalians, Methodists and certainly not Jews.

‘Father, father,’ a boy asked, hand stretching up and waving. ‘What happens to everyone else? To the Protestants and the Jewish people?’

‘They do not enter the Kingdom of Heaven.’

‘What about Gandhi, father, and what about people who are good like the vicar in the Proddie church? Do they go to the Kingdom of Heaven?’

‘No.’

‘Do they burn in the fiery furnace for all eternity, father?’

‘Not always. God is merciful and people who are good but not part of the one true faith go somewhere called limbo. Babies go to limbo if they die before baptism.’

‘Is limbo nice, father?’

‘Yes, Somerville. Limbo is nice, but not as nice as heaven.’

My childhood was shaped by Roman Catholicism, my mind trained like an espaliered apple tree. And although there is rich history, elegance and much good in the Roman Church, what I’ve since learned of the centuries of corruption, and what I’ve heard, not to mention experienced, of their sexual abuse of children means that it no longer has credibility for me. Despite advocating confession and penance, the Roman Church, right up to the last pope, denied its terrible crimes against children – not three times, like St Peter, on whom the church was founded, but time and time again – admitting to the truth only long after its dishonesty has been uncovered. They have now said sorry. But where is their penance?

Astonishingly, given the facts of recent history, the Roman Catholic Church continues to pronounce on what it claims are God’s own views about sexual relations between consenting adults. Apparently, God doesn’t want you to use a condom or take the pill because although He made sex He made it for procreation. God doesn’t want you to be homosexual either, a kind of sex that’s been going on within the church for ever – particularly since marriage was forbidden in order to stop priests passing their property to their children instead of the church. It beggars belief.

Limbo was officially retired by the Roman Catholic Church in 2007, and the babies who died prior to baptism, not to mention Gandhi and the saintly vicar from the Anglican church down the road, are now presumably free to enter heaven. It’s all too little too late for me.

1Dylan Thomas, ‘The force that through the green fuse drives the flower’,18 Poems(1934).

THREE

MCI

A bomb is a terrible thing.

The first of the young people arrive at the Sourasky Medical Center in Tel Aviv within eleven minutes of the blast. They’re drenched in blood but it’s soon clear it’s not theirs: the blood is from the dead on site, or the injured about to arrive.