Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

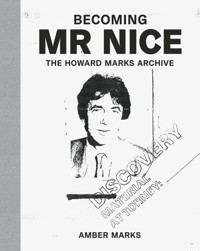

Welcome to the personal archives of Britain's biggest dope smuggler. For 40 years Howard Marks traversed the globe: an international businessman who became an inmate in America's toughest penitentiary before standing for election in the United Kingdom. Becoming Mr Nice reveals an extraordinary montage of previously unseen material from his roller-coaster life, interwoven with his daughter's incisively researched and deadpan commentary. It includes intelligence reports, phone transcripts, the business cards and letterheads used as trading fronts, and cryptic faxes from the Far East. But more than that, it offers a vista onto his many and varied experiences and escapades, through notebooks, personal items and correspondence with the characters who surrounded him. It includes extracts from a lavishly detailed and hitherto unpublished account of Howard's years on the run (written in confidence for the benefit of his otherwise baffled defence team) along with transcripts from his trial at the Old Bailey, in which he successfully claimed that his involvement in the biggest ever importation of cannabis into the United Kingdom was on behalf of the secret services. Peppered with comic observations from Howard's private letters, this book provides a uniquely personal insight into one of Britain's most remarkable characters.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 237

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Becoming Mr Nice

Thank you for downloading Becoming Mr Nice by Amber Marks. As this is a highly illustrated book, the main text is interspersed with images and captions. Please note that by default the main text appears in a serif font, while the captions for the images are in a sans serif font. If you choose to change the font style on your e-reader, this distinction may be lost.

Due to the complex layout of this title and the number of illustrations included, some aspects of the design are compromised in the digital format. Although the eBook still provides the complete text and images, to experience the full impact of Becoming Mr Nice we recommend purchasing the hardback edition instead.

Contents

Preface

1 From the Valleys to the Dreaming Spires(1945–67)

2 Transatlantic Sounds(1967–74)

3 On the Run(1974–80)

4 Regina v Dennis Howard Marks(1981–82)

5 Operation Eclectic(1982–89)

6 Defence Theory(1990)

7 Terror Hut(1990–95)

8 Mr Nice(1995–2016)

Acknowledgements

References

HT

David Leigh, High Time: The Life and Times of Howard Marks (Heinemann, 1984)

HMP

Paul Eddy & Sara Walden (Eds.), Hunting Marco Polo: The Pursuit of Howard Marks (Bantam Press, 1991)

MN

Howard Marks, Mr Nice (Secker & Warburg, 1996)

SMN

Carlo Morselli, Structuring Mr Nice: Entrepreneurial Opportunities and Brokerage Positioning in the Cannabis Trade (École de Criminologie, Université de Montréal, 2000)

JHCH

Thomas Grant, Jeremy Hutchinson’s Case Histories: From Lady Chatterley’s Lover to Howard Marks (John Murray, 2015)

This book is dedicated to my dad and all of those who loved him, with enormous thanks to the custodians of the Howard Marks Archive for its maintenance and for allowing me to access, research and reproduce selected contents in this keepsake.

Preface

‘It is impossible to control what happens to you. The only thing you can control is your attitude to it.’

– Howard Marks

Becoming Mr Nice tells the life story of Howard Marks through his published and unpublished writings, hitherto unrevealed court transcripts, photographs, the smuggling records missed in police searches, and personal mementos. Every image in this book has been scanned or photographed from Howard’s valuables, a biography told by treasured objects. Notwithstanding an unusual and peripatetic lifestyle including two bouts of incarceration, first in the United Kingdom (1980–82) and later in the United States of America (1988–95), several years on the run throughout Europe (1974–88) and multiple bases in the Far East, Howard succeeded, with the help of friends and family, in preserving this collection of artefacts. Howard and I pulled most of these together in the final years of his life, storing it in a large wooden shed in the backyard of his rented apartment in Leeds. It is my pleasure to share many of its highlights in this book. Detailed captions to the images, based on my personal knowledge and archival research, combine with the text of Howard’s own writings to guide us through the images chronologically.

The book opens with a telegram from Captain Dennis Marks of the Merchant Navy, welcoming his son Howard to the world in August 1945, some three weeks before the end of World War II. From his childhood thoughts on philosophy and friendship (in scanned extracts from Howard’s school books) we move to the rebellious years of his adolescence in South Wales and his surprise acceptance into Oxford University in 1964. Much of the text in this chapter will be familiar to readers of Mr Nice. It was originally written at the request of John Jones, Dean of Balliol College, while Howard was serving a prison sentence of twenty-five years in Terre Haute, Indiana, and I have taken the text from this typed manuscript, ‘Reminiscences of Balliol’. We follow Howard’s activities during the height of London psychedelia and learn of his dismay at the policing of anti-Vietnam protests in a letter to his parents. The smuggling life of a budding entrepreneur takes off in the early seventies with driving licences and passports in multiple identities, including that of film director Donald Nice and TV engineer Mr Tunnicliffe. Howard’s headline-grabbing disappearance in 1974 and fugitive years are chronicled with extracts from a hitherto unpublished account, the accuracy of which cannot be vouched for as it was prepared for his court case. This is followed by Her Majesty’s Customs & Excise’s ‘Operation Cartoon’, featuring photographs of Howard’s involvement in the biggest ever cannabis importation into the United Kingdom, apparently on behalf of the Mexican Secret Service. The first half of the book culminates in hitherto unseen court transcripts of his spy-scandalriddled trial at the Old Bailey in 1981, where, to the fury of law enforcement, he is acquitted by the jury.

Things become hectic following Howard’s release from custody in 1982. His voice is lost in the confusion of the world as we hurtle our way towards the height of the Drug War. Records from the appropriately named ‘Operation Eclectic’, then the largest international collaboration of law enforcement, and spearheaded by the US Drug Enforcement Agency, piece together Howard’s life through graphs, phone tap transcripts and investigative leads. The emotional toll of Howard and his wife Judy’s arrests in Palma de Mallorca and extradition to the United States is laid bare through contemporaneous witness statements and correspondence. Previously undisclosed manuscripts reveal the audacious defence Howard would have run, and enjoyed running, had the DEA not succeeded in coercing his partner in crime, Ernie Combs of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, to give evidence against him.

An intimate look at Howard’s time in one of the United States’ highest security penitentiaries provides a rare glimpse into the harsh reality of mass incarceration. Sentenced to 25 years, his prison letters show how he secures his miraculously early release in 1995 and reveal the emotional highs and lows of this time. The final chapter relates his conversion in the press from heinous drug baron to the popularly acclaimed cultural icon and celebrated cannabis activist, Mr Nice.

I hope you enjoy his story as much as Howard did and would have wanted you to.

Amber Marks

1

From the Valleysto the Dreaming Spires

Howard’s father, David Thomas Dennis Marks joined Reardon Smith Ships in October 1929 aged 16. He was made Captain in 1944, while serving in the Merchant Navy during WWII.

Captain Dennis Marks sent this telegram on hearing of Howard’s birth on 13 August 1945. Shortly after his return home to Wales and towards the end of his 21 years in service, Captain Marks was allowed to take Edna, a school teacher, and their son Howard (aged three) round the world on the Bradburn, a 10,000-ton freighter owned by Reardon Smith and Co, Cardiff.

Howard pictured with his parents in Malmö, Sweden, on one of the Bradburn´s many stopovers.

Howard experimented with aliases from an early age, signing this work ‘Howardo de Viccin’. He named the boat The Linda, after his beloved younger sister.

The I-SPY books were popular with school children throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Upon completion, the books were sent to the HQ of the I-SPY Tribe and returned with an Order of Merit. Howard completed several dozen of these booklets. In this letter, dated 27 August 1958, shortly after Howard’s 13th birthday, the Headquarters of the I-SPY Tribe thanks him for his smoke-signal and for informing HQ of the name that Howard believed to be of the shortest street in the world.

Howard as a young boy.

Marty Langford and Howard grew up together in the small village of Kenfig Hill, in Bridgend County Borough, South Wales. In 1980 Marty pleaded guilty to his role in one of Howard’s cannabis ventures. Both keen photographers from a young age, this photo of Howard trainspotting was taken by Marty and developed by Howard in the darkroom he set up at home.

Howard’s school books include an essay on the importance of clear thinking. Here he quotes ‘Men fear thought as they fear nothing else on earth’ from Why Men Fight by the philosopher and pacifist Bertrand Russell, of whom Howard was a fan from an early age. Around the age of 13, Howard was given three months detention for leading a strike against the poor quality of the school dinners.

In Howard’s essay on ‘A Sense of Humour’ he says it is the most important quality in a companion, quite sure he would rather be cheered up than sympathised with.

Chief amongst Howard’s interests were music and Shakespeare’s plays. Howard was allowed to pursue these after obtaining good results in his O Level examinations. A music venue, Van’s Teen and Twenty Club, opened up in Kenfig Hill and Howard occasionally sang rock ’n’ roll songs there.

Howard in his Teddy Boy years.

Valley Boy1945–64

The text for this chapter is taken from a bound typescript written by Howard while serving a 25-year sentence in United States Penitentiary, Terre Haute, Indiana. It was completed at the request of John Jones, Dean at Balliol, to whom Howard sent his recollections in separate instalments over the course of the year between 1991–2. In a letter to John dated 7 July 1991, he writes, ‘You can probably infer from its output that this typewriter is mechanical and is not blessed with anything approaching a word-processing facility. It was recently manufactured in Brazil and resembles those popular in Welsh villages during the early fifties.’

‘Garw’ is a Welsh word meaning ‘rough’, and Pontycymer is the penultimate village in what used to be a coal mining valley terminating in a dead end. The radius of the school’s catchment circle was about fifteen miles. I lived precisely eleven miles away from the school gates, but the school bus took almost an hour to make the journey. The bus was jokingly referred to as ‘yellow dog’ on account of its propensity to stop at every lamp post. There were no extra-curricular activities of any sort.

A school uniform existed, but very few pupils wore it. The school playground and classrooms were subject to frequent invasions of sheep meandering off the mountainside. One illustrious Old Boy could be boasted of – Daniel Davies, the Queen’s Physician.

My ‘A’ level subjects were Pure and Applied Mathematics, Physics, and Chemistry. Although competent in these subjects, I had little or no interest in them and absolutely no interest in any other academic discipline. My interests overlapped my obsessions and were limited to sex, alcohol, and rock ’n’ roll music; all of which were vigorously and passionately pursued. It was an overwhelming surprise when my headmaster, H J Davies, took me aside one day and said that he wanted me to sit the Oxford Entrance Scholarship Examination. It had been at least eight years since anyone from the Garw Grammar School had attempted to get into Oxford. The person who had attempted it had been successful and was, in fact, the headmaster’s son John Davies, who read Physics at Balliol. Accordingly it was suggested that I try to do precisely that.

Sometime during the autumn of 1963, I attended at Balliol for a preliminary interview. I remember little about the train journey from Bridgend to Oxford. I sat opposite a man holding a pair of handcuffs, and for the first time, I saw the dreaming spires. A couple of hours later, I was waiting outside to be ‘generally’ interviewed. Also waiting was another interviewee who asked me which school I came from. I told him. ‘Where’s that?’ he asked. I answered. ‘Oh Wales!’ he said very scornfully. I asked him which school he came from. ‘Eton,’ he said, looking down at the floor. I couldn’t resist asking, ‘Where’s that?’ but he didn’t reply. In fact I did not know Eton’s geographical location, but I must admit that I had heard of it. Eventually I began talking to another grammar school boy who was from Southampton. He too intended to read Physics and also seemed to feel as out of place as I did. His name was Julian Peto, and he has remained absolutely my best friend ever since. □

Howard befriended Julian Peto while being interviewed for a place at Balliol College. Both were grammar school boys and came from very different backgrounds to most of those interviewed. They were surprised by their own and each other’s admission into Balliol, having been convinced by the derision of other candidates that neither stood a chance. In January 1964 they wrote to inform and congratulate each other on their news. This is Julian’s letter to Howard. Julian Peto is now Professor of Epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

First Year at Balliol1964–65

During early October 1964, the big day arrived and I began life as a fully enrolled Balliol undergraduate. I was assigned a small, poky, and drab room on the ground floor of Staircase XXI overlooking St. Giles and vulnerable to inspection by passers by. The gloom of my immediate environment was quickly shattered by an elderly gentleman wearing a white jacket. He knocked on the door, opened it, walked in, and said, ‘Be your scout, George.’ George and I spent a long time talking to each other, and he explained that his duties included making my bed, cleaning my room, and washing my dishes. This information I found totally astonishing.

Although having little, possibly nothing, in common with my fellow Physics students (always, of course, excepting Julian Peto), there was certainly no feeling of animosity in any direction. Other Physics freshmen were courteously friendly towards me and came to comprehend my heavy Welsh lilt. I gradually began to meet Balliol students outside of the Natural Science faculty and formed the opinion that arts undergraduates, particularly historians and philosophers, were a far more interesting and nonconforming bunch than scientists. Some of them had long hair and wore jeans. Ones that come to mind are: John Adams, Arnold Cragg, Henry Hodge, Chris Fagg, and John Rhodes. A nodding acquaintance with such individuals began to develop.

After a couple of weeks of my first term, a notice appeared in the Porter’s Lodge announcing that: ‘The following gentlemen will read essays to the Master on the subject of “The Population Problem”.’ My name then followed along with about six others whose surnames also began with L, M or N. Also present at this essay reading were freshmen John Minford and Hamilton McMillan, both of whom had a very significant effect on my life. John Minford was convinced that I was a talented actor and persuaded me to join the Balliol Dramatic Society. Hamilton McMillan, many years after graduation, was convinced that I would make a talented espionage agent and persuaded me to work for MI6.

Henry Hodge was one of the immediate neighbours of mine with whom I had a close personal friendship. He was one of the users of my window with removable bars; his girlfriend then being Emma Rothschild. Henry often spoke of his friend Denys Irving, who had been rusticated from Oxford for that particular academic year and had sensibly spent that year visiting exotic parts of the world. He had recently returned from his voyages of discovery and was about to visit, presumably illegally, his friends at Oxford. There were a number of friends of Denys who had gathered at Chalfont Road. I was invited over there to meet him and join in a social gathering. I felt fairly honoured to be invited to join the ‘big boys’ and looked forward to the engagement.

Denys had brought with him some marijuana in the form of kif from Morocco. Up to that point I had heard the odd whisper of drugs being taken at the University and was aware that marijuana was popular with British West Indian communities, modern jazz enthusiasts, American beatniks, and the British self-styled intellectual wave of ‘angry young men’. I still, however, had not consciously retained any description of the effects of marijuana. With a great deal of enthusiastic interest, therefore, I accepted the joint that was offered and took my first few puffs.

I became an active member of the Balliol Dramatic Society and was soon adopted into a group of largely second-year Balliol undergraduates often referred to as ‘The Establishment’. These included the long-haired trio of Chris Fagg, John Rhodes and John Adams and others such as John Hamwee, Roger Silverstone, Rick Lambert, Michael Wilkins, Peter Ford and Paul Swain. I greatly enjoyed their company and spent most of the day with them. ‘The Establishment’ also formed the core of the Victorian Society and invited me to become a member. It was a strange society, to say the least, but the main requirement was to down large amounts of drink – this time port, which I had never tried.

For their Hilary Term production, the dramatic societies of Balliol and Lady Margaret Hall chose Oscar Wilde’s Salomé. John Minford, the producer, asked if I would play the part of John the Baptist. The part was not a very large one, and most of my lines had to be bellowed from a makeshift cistern constructed in an alcove which normally housed a piano. Minford felt that my Welsh accent might add some authenticity to the evangelical wailings emitting from the cistern. Salomé herself was played by Vivien Rothwell and one of the palace guards was played by Hamilton McMillan. At some stage – mercifully offstage – John the Baptist was beheaded. This required a model to be made of my head and for this model to be adorned with bloody entrails obtained from one of the city’s butchers. The end result was placed on a silver platter for presentation to Salomé.

The first and last three weeks of my first long vacation were spent at my parents’ house in Wales, while the intervening ten weeks were spent hitchhiking fairly randomly around Great Britain and Europe. My European travels included a visit to Copenhagen, where I ran completely out of money. Luckily, I had made friends with members of a Danish rock and roll group, who very kindly allowed me to sing with them on a few occasions thereby earning enough money to leave the country. The route back to the United Kingdom took me through Hamburg, where my friend Hamilton McMillan lived. Mac had given me his particulars, and I telephoned him from a sordid bar in the Reeperbahn. (I was looking for the Star Club where the Beatles had been discovered.) He was delighted to hear from me, insisted I stay a few nights at his home, and came to pick me up. □

Letter to Howard from Julian Peto on 28 December 1964 proposing a visit to Wales by Julian and his brother Richard.

Howard in thespian mode in his parents’ garden in Kenfig Hill.

Howard played the part of John the Baptist in this production of Oscar Wilde’s tragedy Salomé.

Letter and invite from Howard’s college friend, Vivien Rothwell.

In 1991, while serving a 25-year sentence of imprisonment in United States Penitentiary Terre Haute, and at the request of Dr Lester Grinspoon of Harvard Medical School, Howard wrote an 11-page narrative of how he found marijuana useful in his life and his experience of it. These are the second and third pages, where Howard describes his first experience of marijuana.

The British Visitor’s Passport was a simplified version of the standard passport, introduced in 1961. It could be obtained from any Post Office on provision of the applicant’s birth certificate. It was only valid for one year and intended simply for holiday, or similar purposes not exceeding three months in duration. It was withdrawn in 1996 on account of security concerns.

Howard on his summer vacation in Malmö (Sweden), August 1965.

Second Year at Balliol1965–66

During my continental episodes of the long vacation, I had picked up a varied assortment of ethnic rubbish, pretentious objets d’art, gimmicky knick-knacks, and other hippie software with the intention of using them to decorate my room. These included a 400 sq ft net (used to protect fruit trees from birds), a road sign stating ‘Mind the Hose’, a very large Cezanne poster, and rolls of aluminium foil wallpaper. I suspended the net from the room’s ceiling, papered the walls with aluminium foil, and nailed the Cezanne poster to the floor. Some homemade lamps (orange boxes containing low-wattage coloured bulbs) were carefully placed in corners, and my newly acquired record player was set up with extension speakers dotted around the walls.

All and sundry were welcome to visit my new quarters and bring their friends, records, alcohol and supplies of marijuana and hashish. My rooms rapidly became the location of a non-stop party with music blaring and dense clouds of marijuana smoke billowing out of the door and windows. Terry Deakin, a Merton Egyptologist, actually lived there and the constant sight of the net, which he spent many days gazing at while lying on the floor, inspired him to write a poem (appropriately called ‘The Net’), which was later published both in Richard Branson’s magazine, The Student, and a Deakin anthology of poems entitled Testament of a Roach Eating Saint. Various ‘townies’ would also visit, as would the odd member of the London ‘underground’ and the occasional student from other universities. The fame of this dope-smoking haven, enshrined and protected by College and University, had spread far and wide.

Balliol, in conjunction with St John’s College, Cambridge, occasionally produced a satirical magazine called Mesopotamia. Apparently, the Cambridge proponents of the first issue went on to produce Private Eye. The Balliol side of the enterprise was controlled by The Establishment. I was appointed Business Editor and was responsible for raising advertising revenue and organisation of sales. For some reason there were some nude photographs of me featured in the magazine, but I cannot remember why. Life became quite hectic during this Hilary Term: an abundance of parties; lots of dates; and a never-ending sequence of Dramatic Society and Victorian Society evenings. I was thoroughly enjoying myself and was not looking forward to returning home to Wales. I stayed on at Balliol for as long as the rules permitted, seeking out and attending every possible social occasion. Eventually, the college closed and I returned home, where I spent Easter drinking, sleeping and missing what had now become a truly exciting student life.

Mesopotamia was a satirical magazine produced as a collaboration between Balliol College, Oxford and St John’s College, Cambridge. This issue was edited by Hamilton McMillan (responsible for Howard’s subsequent recruitment to the British Secret Services). Howard served as Business Editor alongside Julian Peto.

I was elected to organise the entertainments for the forthcoming 700th anniversary commemorative ball. My primary duty was to engage groups to supply the musical entertainment and I had a budget of £1,000. As far as I can recall, the ball was an outstanding success. I wasn’t able to participate in much of it as I had to spend most of the time ensuring the entertainers were properly catered for and able to perform at the scheduled times. It was, nevertheless, a big thrill for me to smoke marijuana, drink whisky and talk to famous pop singers.

Trinity Term, 1966, was the only term that I really enjoyed to the fullest extent. I’d come to grips with my work, was delighted to be asked to organise a commemorative ball, maintained my hippie existence, drank plenty, smoked loads of marijuana, had abundant sexual adventures and was still able to find time for walks in Christ Church and Port Meadows. After term I stayed on at college until it closed and completed the work that had been set for the long vacation. The third year was to be spent in lodgings, but I postponed the search for suitable accommodation until the following September. □

This postcard to Howard was posted in May 1966. The sender is unknown.

Howard found release from an LSD-triggered depression in his role, custom-designed for a mind-blown Welsh hippy in Marat-Sade.

Terry Deakin (aka Terence DuQuesne) wrote his poem ‘The Net’ about a 400-square-foot net (originally intended for protecting fruit trees from birds), which Howard had brought back from his summer vacation in 1965 and draped from the ceiling of his room. Amongst Howard’s many guests was Graham Plinston, a politics, philosophy and economics student at St Edmunds Hall, in the year below Howard.

Terry sent Howard his essay on LSD, noting that the drug was about to be banned (it was banned in 1966), but that this would not ‘deter those who feel entitled to experiment’. Terry developed an academic interest in pharmacology and co-authored A Handbook of Psychoactive Medicines in 1982. In 1986, Terry published Illicit Drugs: Myth And Reality for the Libertarian Alliance, who presented it as evidence to a House of Commons Home Affairs Committee on the use of illicit drugs. At the same time, with his friend and solicitor Edward Goodman, he published Britain: An Unfree Country, a detailed critique of the erosion of personal freedom under the Thatcher regime.

Poster with original line-up.

Balliol Ball invite.

Howard booked the relatively unknown Spencer Davis Group and the Small Faces for the ball but within weeks of being booked, they both had Number One hits. The agent offered Howard The Kinks, the Fortunes, Them, and Alan Price (all of whom were already top names) for the same price in exchange for letting the Spencer Davis Group and the Small Faces pull out. These are Howard’s contracts for The Kinks and for the Alan Price set.

Poster with revised line-up.

Balliol Ball programme.

Final Year at Balliol1966–67

46 Paradise Square had the dubious privilege of once having housed both Oxford student Paul Jones, who became the lead vocalist of Manfred Mann, and American ‘beat’ novelist William Burroughs. Julian, Steve Balogh and I took one room each. People were always on the lookout for cheap rooms to rent in Paradise Square and shortly after we became registered, a couple of pleasant long-haired hippies knocked on our door and asked if we had any space to let. They had a great many friends who gradually began to take over the house, filling it with delightful marijuana smoke and riveting Jimi Hendrix guitar playing. Julian, Steve and I had very little by way of objection to this development and, once again, my home turned into a place where people from far and wide came to smoke marijuana and generally hang out. I have absolutely no recollection of the 1966 Christmas vacation, but do know that I must have spent Christmas Day, at least, at my parents’ home in Wales. I do, however, vividly remember the commencement of Hilary Term, which was when I fell madly in love with St Anne’s English undergraduate, Ilze Kadegis. Although we had dated each other for about a year, something happened during January 1967 which made us lose our enthusiasm for dating anyone else.

There were some drunken celebrations after finals, some of which took place in the Lindsay Bar. During one of these, I became engrossed in a conversation with the new (actually, by then not that new) Master of Balliol, Christopher Hill. This was the only time I had talked to him outside of handshakings. I’ve no idea now what we talked about, but I remember leaving the bar with a distinct feeling of sadness that I was soon to be no longer a Balliol student.

Ilze and I had decided to move to London and live together in Notting Hill, which was fast becoming the centre of European psychedelia. We had both been enrolled by London University to do the Postgraduate Certificate in Education and expected to gain teaching positions in London during the subsequent years. We were wrong. □

Between 10 December 1966 and 14 January 1967, the English psychedelic rock group Soft Machine (Robert Wyatt, Kevin Ayers, Daevid Allen and Mike Ratledge) had a weekly Saturday night residency at the Zebra Club in Soho, London. Mike Ratledge would become a good friend of Howard’s. This note is from Denys Irving. Denys Irving had given Howard his first joint. The note was written on what appears to be promotional writing paper for sleeping pills containing butobarbitone, phenacetin and codeine, marketed at the time under the brand name ‘Sonalgin’. It was presumably addressed to Howard, Julian Peto and Steve Balogh, at number 46 Paradise Square, Oxford.

Howard larking about in the countryside.

Howard fell in love with Ilze Kadegis, a Latvian undergraduate at St Anne’s College, Oxford.

Howard graduated in 1967.