13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Spellmount

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

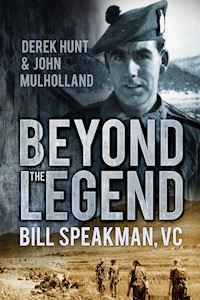

Beyond the Legend is the authorised biography of William (Bill) Speakman,who was awarded one of only four Victoria Crosses for action in the Korean War. It covers his sometimes controversial life, from his childhood in Altrincham, Cheshire, to his later life in South Africa – about which little has been known previously. Authors Derek Hunt and John Mulholland also explore the myth of the 'beer bottle VC' (in which Speakman was said to have fended off the Chinese Communist Army by throwing empty beer bottles at them after they ran out of grenades), bringing to light what really happened on United Hill in November 1951. Speakman held the attacking Chinese army at bay for over four hours and led a final charge that allowed his company to withdraw from the hill. After Korea, he saw active service in Malaya, Borneo and Aden before retiring from the army, with the rank of sergeant, in 1968. Bill Speakman is one of only two surviving VC holders of the British Army and a true British hero.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Speakman’s VC. (National War Museum of Scotland)

Speakman after receiving the VC ribbon from Major General Cassels in Korea on 30 December 1951. (© IWM KOR/U6)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are indebted to the staffs of the following institutions, which have been of great assistance, many of them allowing us to reproduce material from their archives: The National Army Museum for access to the Canon Lummis VC files, The Victoria Cross and George Cross Association, especially Mrs Didy Grahame OBE MVO, the Secretary of the Association, The King’s Own Scottish Borderers, especially Lieutenant Colonel G. Wood MBE, the regimental secretary, and Lieutenant Colonel G.C.O. Hogg OBE DL, former regimental secretary, William Foster, curator and Ian Martin, archivist, The National Archives at Kew, National Museums of Scotland/National War Museum in Edinburgh, Australian War Memorial, Printed Books Department and the Sound Archive of the Imperial War Museum, British Korean Veterans Association, Altrincham History Society, Jane Carmichael, Director of Collections, National Museum of Scotland and Kate Swann, Department of Archives, Photographs, Film & Sound at the National Army Museum.

We should also like to thank the many newspapers and publishers that have generously given us permission to use short extracts from their publications in this book, including: Sunday Express, The Times, Newsquest Media Group for quotes from the Altrincham, Hale and Bowdon Guardian, and the Canberra Times.

Many individuals have helped us and we should particularly like to thank: Rupert Allison, Reg Clements, John Cowell, Peter Fisher, John Hayward, Medal Consultant at Spink, Peter Hennerley, Colonel Michael Hickey, Christopher Hunt, Tom Johnson BEM, Rose Jones, the late James Murdoch MBE DCM, Sir William Purves CBE DSO, Geoff Scott, Steve Scott-Spence, Peter Arnold, Alan Speakman and the Victoria Cross Database Users Group, comprising Doug and Richard Arman, Vic Tambling, Paul Oldfield and Alan Jordan, with apologies if we have inadvertently omitted to thank anyone.

Our thanks are also due to Gail Balfour and Barbara Hunt for typing/producing drafts of the manuscript.

For the photographs reproduced we would like to thank: Bill Speakman VC, Australian War Memorial, The Victoria Cross and George Cross Association, Imperial War Museum, National War Museum of Scotland, British Pathé, www.militaryimages.net, the late James Murdoch, James Bancroft, Erling Breinholm and John Mulholland. We are particularly grateful for the co-operation and assistance of William Foster, curator and Ian Martin, archivist at the KOSB Museum. Details of the Museum can be found in Appendix IV. Whilst every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders or the photographers of illustrations used this has not always proved possible.

Our special thanks to David Balfour for producing the maps and Mark Adkin for permitting us to use information from one of his maps.

Finally, we are greatly indebted to Bill Speakman VC, without whose assistance this book could never have been written. He generously gave us much of his time, taking part in numerous interview sessions and answering questions, in addition to allowing us access to his Army records and private papers and photographs.

CONTENTS

Title

Acknowledgements

Illustrations

Preface

Abbreviations

Prologue

1. Early Years (1927–1945)

2. Army (1945–1951)

3. Korea (July-November 1951)

4. VC Action (4 November 1951)

5. Aftermath of Battle (5–11 November 1951)

6. Award of the VC (November–December 1951)

7. Homecoming (January–February 1952)

8. Postings (1952–1953)

9. Malaya (1953–1955)

10. UK, Germany, Middle/Far East (1956–1968)

11. Civvy Street: England and South Africa (1968–1980)

12. South Africa and Royal Hospital Chelsea (1980–1997)

13. Re-emergence (1997–2013)

Appendix I Decoration and Medals Awarded to William Speakman VC

Appendix II Awards and Casualties for Korea to The King’s Own Scottish Borderers

Appendix III 22538361 Private P.E. Lydon, Rnf Attached C Company, KOSB

Appendix IV KOSB Museum, Berwick-Upon-Tweed

Bibliography

Copyright

ILLUSTRATIONS

MAPS

Map 1 Korea theatre of operations, 1950–53.

Map 2 Operation Commando, 3–7 October 1951.

Map 3 Chinese attacks on KOSB positions, 4 November 1951.

Map 4KOSB B Company positions on United, 4 November 1951.

PHOTOGRAPHS

001 Speakman’s VC. (National War Museum of Scotland)

002 Speakman after receiving the VC ribbon from Major General Cassels in Korea on 30 December 1951. (© IWM KOR/U6)

003 The Speakman family’s home, 27 Moss Lane, is the house with the Union Flag above the door to commemorate Speakman’s homecoming in 1952. Speakman was born nearby at 17 Moss Lane. (British Pathé)

004 Speakman home on leave. (Bill Speakman VC)

005 Speakman home on leave. (Bill Speakman VC)

006 The two B Company KOSB soldiers in foreground are Lance Corporal John Pender who was to win the MM in the 4 November action (light hat) and Private John Dunbar. The soldiers in background left are Private John Davine and Lance Corporal Ted Arbuthnott DCM MM who won his DCM at Anzio and his MM in Sicily. (© IWM K07607)

007 Lieutenant Colonel J.F.M. MacDonald, Commanding 1st KOSB, and his escort on arrival in Korea. (KOSB Museum)

008 Two views of Hill 355. (KOSB Museum)

009 Hill 355 being bombarded by artillery in Operation Commando. (© IWM BF 10426)

010 Brigadier George Taylor and Captain Donald Lear 1st KOSB watch KOSB advance on Hill 355. (© IWM BF 10427)

011 Taken immediately after capture of Hill 355 on 4 October, in background are men of KOSB. In the foreground are two Chinese POWs watched on right by a South Korean soldier attached to KOSB

012 Hill 317 bombarded with napalm and rockets during Operation Commando. (© IWM BF 10430)

013 View of Hill 317 from the newly captured Hill 355. (Australian War Memorial 042315)

014 Lieutenant Colonel J.F.M. MacDonald, 1st KOSB; Lieutenant Colonel Frank Hassett, 3rd RAR; Lieutenant General Bridgeford; Major General A.J.H. Cassels. (© IWM MH 28035)

015 1st KOSB C Company reconnaissance group being briefed by company commander, Major T. Little. Left to right: Sergeant R. Mitchell, Corporal J. Roberts, Second Lieutenant E.R. Mudie, Captain R.H.S. Irvine, Second Lieutenant W. Purves, Major T. Little MC. (Australian War Memorial HOBJ2379)

016 View of battle area, 4 November 1951. (Bill Speakman VC)

017 View of battle area, 4 November 1951. (Bill Speakman VC)

018 Part of forward left B Platoon of C Company just before the battle. (Major R.H.S. Irvine MC via KOSB Museum)

019 Lieutenant Colonel Tadman, commanding officer 1st KOSB, at a command post (© IWM MH 32343)

020 1st KOSB strengthening barbed wire defences on the forward slopes of their hill. The soldier on the left keeps a lookout with his Bren gun. (© IWM MH 32800)

021 Chinese soldiers on a night offensive in Korea.

022 1st KOSB team with Browning machine gun, guarding front line positions. Left to right: Lance Corporal John Simpson, Private Tom Brown and Private Jim Elliott (© IWM KOR 605)

023 Artist’s impression of Speakman’s grenade charge. (James Bancroft)

024 KOSB 2-inch mortar. On the left is Private Tom Lapere and on the right Private Alec Ewan. (© IWM KOR 601)

025 1st KOSB 3-inch mortars in action. Left to right: Lance Corporal Bill Hunter, Private Jim Beveridge and Private Tony Donaldson. (© IWM KOR 604)

026 James ‘Busty’ Murdoch circa 1948. (John Mulholland)

027 Murdoch’s decorations and medals: MBE (Military), DCM, 1939–45 Star, Burma Star, Defence Medal, War Medal 1939–45, Queen’s Korea, UN Korea, GSM (1918) Malaya with Mention in Despatches, Long Service and Good Conduct Medal. (John Mulholland)

028 Left to right: Second Lieutenant William Purves, Lance Corporal Allison, Private John Common who was decorated with the MM. (Australian War Memorial HOBH 2378)

029 Major Tadman’s address to the KOSB survivors on 11 November 1951. (KOSB Museum)

030 Speakman on 29 December 1951 at Seoul Airport, the day after his VC was gazetted. (KOSB Museum)

031 Speakman about to receive VC ribbon from Major General Cassels, standing in front of table. (Australian War Memorial HOBJ2811)

032 Major General Cassels pinning VC ribbon on Private W. Speakman VC. (Australian War Memorial HOBJ2812)

033 Speakman after the ribbon ceremony. (© IWM KOR/U5)

034 Speakman being congratulated by his comrades after the ribbon ceremony. (Bill Speakman VC)

035 Speakman phones his mother. (KOSB Museum)

036 ‘That’s when it all started …’ Speakman faces the media as he leaves the aircraft at RAF Lyneham 29 January 1952. (British Pathé)

037 Speakman is met at the foot of the aircraft at Lyneham by the Mayor of Altrincham, Councillor Warren. (British Pathé)

038 Speakman meets with Major General E.G. Miles, the Colonel of KOSB, in London. (KOSB Museum)

039 Speakman accompanied by Mayor of Altrincham. (British Pathé)

040 Speakman examines the VC of Sergeant John Thomas VC. (British Pathé)

041 Welcome home sign in Altrincham. (British Pathé)

042 Speakman finally arrives at the family home in Moss Lane to embrace his mother. On the left is a relation called Savage. The Mayor of Altrincham is behind. (British Pathé)

043 Obverse and reverse of Speakman’s VC. (National War Museum of Scotland)

044 Outside Buckingham Palace after the investiture. Left to right: Mrs Warren, Speakman VC, Hannah Houghton, Mayor Warren. (British Pathé)

045 FM Lord Alexander, Defence Secretary, shaking hands with Lieutenant Colonel Tadman, June 1952. Major General Cassels is to Lord Alexander’s left. (© IWM BF 10727)

046 Newspaper reporting Speakman’s return to Korea. Speakman on the right. (Bill Speakman VC)

047 Speakman outside a bunker. (KOSB Museum)

048 Speakman examining the graves of fallen KOSB comrades at Pusan on 12 August 1952. (© IWM MH31495)

049 Speakman being interviewed in Berlin. (Bill Speakman VC)

050 Speakman, wearing SAS cap and shoulder badges in June 1953. (Bill Speakman VC)

051 Speakman’s Hill. (Bill Speakman VC)

052 Lance Corporal Bill Speakman VC shakes hands with fellow Korean VC recipient Lieutenant Colonel James Carne VC DSO outside Wellington Barracks, London during the VC Centenary celebrations in June 1956. (Bill Speakman VC)

053 Speakman’s invitation to the 1956 VC Centenary celebrations. (KOSB Museum)

054 Speakman at Café Royal 24 July 1958 Left to right: Viscount De L’Isle VC, Speakman VC, Major D.S. Jamieson VC and Major Nigel Macdonald. (VC & GC Association)

055 Speakman with Air Commodore Freddie West VC at the Café Royal 24 July 1958. (VC & GC Association)

056 At a recruiting table at a country show. Left to right: Sgt Speakman VC, Sergeant Fraser, Sergeant Johnstone. (Bill Speakman VC)

057 Speakman at Leith in 1961 with Lieutenant General W.R.F. Turner CB DSO. (KOSB Museum)

058 HM The Queen inspects a guard of honour, Edinburgh on 27 June 1961. Speakman is on the right. (Bill Speakman VC)

059 Speakman’s uniform on display at KOSB Museum. (John Mulholland)

060 On the deck of troopship Oxfordshire at Southampton on 6 February 1962. Left to right: Lance Corporal Brown, Lance Corporal McCormick, Lance Corporal Tennant, Sergeant Speakman VC, Lance Corporal Hunter, Lance Corporal Henderson. (KOSB Museum)

061 Speakman arriving in Singapore on board Sir Lancelot on 30 July 1965. (Bill Speakman VC)

062 Speakman’s portrait now in the Officers’ Mess in Dreghorn, Edinburgh. (KOSB Museum)

063 Speakman on guard duty at Edinburgh Castle. The boy was the son of Steve Milner, a KOSB soldier who liked to dress him in uniform. (Bill Speakman VC)

064 Speakman arrives at lunch for VC and GC recipients at Buckingham Palace 1968. (British Pathé)

065 Speakman’s VC group as purchased in 1968 by John Hayward and now on display in the National War Museum of Scotland. (National War Museum of Scotland)

066 Speakman wearing his medals in the summer of 1968 shortly before they were sold. (British Pathé)

067 Allandale, Wyton, St Ives, Huntingdonshire. Speakman’s VC was sold to re-roof the property in 1968. (John Mulholland)

068 The Speakman family home in Avenue Road, Torquay, purchased with the proceeds of the sale of Allandale. (John Mulholland)

069 RMS Windsor Castle sailing from Cape Town for the last time. (Bill Speakman VC)

070 Speakman’s VC. (National War Museum of Scotland)

071 HM The Queen Mother speaks with Speakman with two of his daughters at St James’s Palace, November 1990. (IWM/VC & GC Association)

072 HRH The Duke of Edinburgh speaks with Speakman. On the left is Rear Admiral Place VC DSC, Buckingham Palace, November 1990. (VC & GC Association)

073 Speakman in his Chelsea Pensioner’s uniform at a social event in 1994. (Bill Speakman VC)

074 Speakman in Sweden in 1994. (Bill Speakman VC)

075 Marylyn Jones at 2005 VC & GC Reunion held at Royal Hospital Chelsea. (VC & GC Association)

076 Speakman outside St Martin-in-the-Fields, Trafalgar Square at a VC & GC Memorial Service. (Erling Breinholm)

077 Speakman with his wife Heather with the Duke of York at Locarno Suite, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, May 1997. (VC & GC Association)

078 Speakman outside the entrance of Westminster Abbey at the ceremony to unveil the VC & GC Memorial, 14 May 2003. (Erling Breinholm)

079 Speakman unveils plaque at Speakman’s Bridge, Altrincham, 20 May 2003. (Bill Speakman VC)

080 The plaque on Speakman’s Bridge, unveiled 20 May 2003. (John Mulholland)

081 Speakman’s plaque at the National Arboretum, Staffordshire. (www.militaryimages.net)

082 HM The Queen speaks with Speakman. In the middle is Maureen Richardson, widow of G. Richardson GC, and her partner, Charles Telling. (IWM/VC & GC Association)

083 Minden Day, Berwick-upon-Tweed, 28 July 2008. Three decorated Korean veterans, left to right: Bill Speakman VC, James ‘Busty’ Murdoch MBE DCM and John Common MM. (KOSB Museum)

084 Speakman Court at the junction of Barrington Road and Gaskell Road, close to Speakman’s Bridge. (John Mulholland)

085 Wreath and note laid by Speakman at Busan. (Bill Speakman VC)

086 Bill Speakman at the UN Memorial Cemetery. To his left in the light coat is Derek Kinne GC. (Bill Speakman VC)

087 Speakman relaxes at home in 2010. (John Mulholland)

088 Speakman after receiving his VC ribbon from Major General Cassels in Korea on 30 December 1951. (Australian War Memorial HOBJ2809)

PREFACE

Anyone growing up in the 1950s and 1960s, as we did, would have been familiar with the story of ‘Big Bill’ Speakman VC. He was, literally, a larger than life hero and his exploits in holding off a Chinese attack on a hilltop in Korea for over four hours had become a legend. But while the details of how he won his Victoria Cross were well known, almost nothing was known about the man behind the legend.

Bill Speakman, despite his physical size, is a shy and modest man and does not seek attention and rarely talks about himself. Although he has been mentioned in several books about the VC and the Korean War, he has never contributed to a biography or written his memoirs.

We had a chance to meet Bill and get to know him better a few years ago and later he kindly agreed to write the foreword to one of our previous books. Following on from those first meetings, when we became friends, he requested us to write his biography. We have always respected and admired Bill Speakman and were delighted to be offered this unique opportunity to write about him.

He has spared us the time to be interviewed, covering every aspect of his fascinating life, and has allowed us access to his personal records as well as providing answers to the many queries which arose during the course of writing. In this book, the first biography of Bill Speakman VC, we have disproved all the myths surrounding his life and how he won his VC as well as giving an account of the VC action in his own words. We have also covered his childhood in Altrincham and his later life in South Africa – a period about which little has been known previously – and have looked beyond the legend.

Derek Hunt and John Mulholland, 2013

ABBREVIATIONS

A&SH

Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders

AWOL

Absent Without Leave

BAOR

British Army of the Rhine

BCOF

British Commonwealth Occupation Force

BEM

British Empire Medal

BKVA

British Korean Veterans Association

CB

Companion of the Order of the Bath

CBE

Commander of the Order of the British Empire

CCS

Casualty Clearing Station

CDC

Civil Defence Corps

CMF

Central Mediterranean Forces

CO

Commanding Officer

CSM

Campaign Service Medal/Company Sergeant Major

CT

Communist Terrorist

DCM

Distinguished Conduct Medal

DF

Defensive Fire

DL

Deputy Lieutenant

DP

Displaced Person

DSO

Distinguished Service Order

ERE

Extra-Regimentally Employed

FARELF

Far East Land Forces

GC

George Cross

GCB

Knight Grand Cross, Order of the Bath

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

GHQ

General Headquarters

GOC

General Officer Commanding

GSM

General Service Medal

HM

His/Her Majesty

HMSO

His/Her Majesty’s Stationery Office

HQ

Headquarters

HRH

His/Her Royal Highness

KBE

Knight Commander, Order of the British Empire

KD

Khaki Drill

KOSB

King’s Own Scottish Borderers

KSLI

King’s Shropshire Light Infantry

LRDG

Long Range Desert Group

MBE

Member of the Order of the British Empire

MC

Military Cross

MCP

Malayan Communist Party

MM

Military Medal

MMG

Medium Machine Gun

MP

Member of Parliament

MVO

Member of the Royal Victorian Order

NAAFI

Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes

NCO

Non-Commissioned Officer

NHS

National Health Service

NLF

National Liberation Front

OBE

Officer of the Order of the British Empire

POW

Prisoner of War

RAF

Royal Air Force

RAR

Royal Australian Regiment

RMS

Royal Mail Steamer

RNF

Royal Northumberland Fusiliers

RSF

Royal Scots Fusiliers

RSM

Regimental Sergeant Major

TB

Tuberculosis

SAS

Special Air Service

TD

Territorial Decoration

UK

United Kingdom

UN

United Nations

US

United States

VC

Victoria Cross

VE DAY

Victory in Europe Day

VJ DAY

Victory over Japan Day

PROLOGUE

When news was received that two members of an SAS patrol had been killed in a terrorist ambush in the jungle, plans were made for the immediate recovery of their bodies. A helicopter was requested to fly them back to base for a proper burial, but first the dead soldiers had to be brought out of the jungle.

It was November 1953 and Britain faced a new type of enemy in the jungles of Malaya – communist terrorists (CTs). The CTs had grown from the resistance groups which Britain had supported and armed in the fight against the Japanese occupiers during the Second World War. After the end of the war, however, the communists planned to seize power for themselves. A campaign of killing rubber planters and tin miners later developed into a lengthy guerrilla war against colonial rule, which became known as ‘The Emergency’. British and Gurkha troops were sent to restore order, with the SAS being in action for much of the conflict. The 22nd Special Air Service worked deep in the jungle, sending in small patrols, often no more than four men, to seek the enemy and kill them.

An SAS patrol, under the command of Corporal K.B. ‘Digger’ Bancroft, ran into a CT ambush and Bancroft and Trooper F.W. Wilkins were killed. The rest of the patrol engaged the enemy, who retreated into the jungle. News of the deaths was sent by runner and received by C Squadron commander, Captain Johnny Cooper – one of the original founders of the SAS during the Second World War.

Cooper had been given the task of penetrating the thick jungle in the mountains of Pahang to establish a fort from which to control the local area and send out patrols. The clearing of the site and construction of a helicopter landing area were progressing to plan when the patrol was ambushed and the two SAS men killed on 26 November 1953. This tragedy marked the only British deaths during the squadron’s 122 days in the jungle. Captain Cooper informed headquarters and a helicopter was put on standby to collect the bodies; it was considered a priority to bring back fatal casualties for burial.

Trooper Bill Speakman VC, a Korean War veteran who had joined the elite regiment less than six months earlier, was one of the men who volunteered to go into the jungle to recover the bodies. He had known both men and wanted to do whatever he could to help. At 6ft 6in tall and well built, he was ideal for such a dangerous mission. The rescue party set off on foot towards Bancroft’s base, while another party continued to search for the enemy. The next day, around noon, Speakman returned to camp carrying Corporal Bancroft strapped to a bamboo pole across his shoulders. Three other SAS troopers supported the back end of the pole.

The body was placed near the waiting Royal Navy helicopter and a second recovery party organised to bring back Trooper Wilkins. Bill Speakman volunteered once more, saying that he should go as he was stronger than the others, and went back into the jungle. When the volunteers returned, Speakman was again in the lead taking the weight of the second body on a bamboo pole across his broad shoulders. Both dead SAS men were then flown out and were buried in Cheras Road Christian Cemetery (Military Annex), Kuala Lumpur. Corporal Bancroft’s parent unit was the East Surrey Regiment and Trooper Wilkins’ parent unit was the Army Catering Corps. Johnny Cooper later wrote about the ambush and the jungle rescues in his memoirs (1). Trooper Speakman was typically modest about his part in the two rescue missions:

I was laid up beforehand because I had cut my feet to ribbons. Unfortunately they could never find jungle boots to fit me. I was told to stand down for a while because a soldier has to have two feet working. So I stayed behind for a couple of days to get my feet treated; because of the weather they were giving me problems with septic healing up. While I was laid up I did some administration duties in the fort and I was there when Digger Bancroft, who I knew personally, and a trooper got ambushed.

Johnny Cooper said: ‘Look, we have to get those guys out.’ Everyone else was out on patrol and couldn’t be called in. Once an SAS patrol was in the jungle no one knew where they are and that is the whole point of a secret patrol. So I said; ‘I’ll go, sir’. We went in and got one body out but couldn’t get the other one. We brought the first one, which was Digger, out on a bamboo pole. Johnny Cooper said: ‘We have got one more body to retrieve.’ So we went back and found Trooper Wilkins and brought him back. I think we carried him out on a pole as well.

These rescue missions were dangerous for all involved, because of the risk of further terrorist ambushes, but more so for Speakman as he had no adequate footwear. Because of his size it was impossible to obtain boots that fitted him. Size fourteen jungle boots were just not available and so he had to wear a smaller size with the toes cut out. This made walking through the jungle hazardous and, not surprisingly, his feet were severely cut and injured when he returned to camp. He had cut his feet to ribbons before they had healed properly following a previous venture into the jungle.

Displaying the same courage and determination he had shown in the Korean War two years earlier, Speakman accomplished his mission. He received no award for the jungle rescues and, although he was mentioned in a report by Captain Cooper, he did not receive an official Mention in Despatches. For the earlier act of heroism when besieged on a hilltop in Korea he had been awarded the nation’s highest award for valour: the Victoria Cross.

NOTE

(1)One of the Originals: The Story of a Founder Member of the SAS by Lieutenant Colonel John Murdoch Cooper MBE DCM. (Pan Books, London, 1991)

1

EARLY YEARS

1927–1945

‘Big Bill’ Speakman VC has not always enjoyed an easy relationship with the media. In fact, for much of his life, this relationship has been characterised by resentment and suspicion. It all started off so well, with the media displaying genuine affection for the young VC winner, so where did it go wrong?

Speakman returned home to a hero’s welcome in January 1952 after being awarded the Victoria Cross for his gallant stand against a Chinese attack on United Hill in Korea. He had organised a defence against thousands of enemy soldiers who were as determined to capture this position as he was to defend it. Back in England his heroism had made him a legend and he was greeted at RAF Lyneham by huge numbers of newspaper reporters, photographers, television and newsreel cameramen and well-wishers. All of this was unexpected and he was completely overwhelmed by the media attention he received. As he would later remark, his life changed the moment he stepped off the plane. Over the following weeks the media were at every event he attended – every official reception, football match and dinner dance. He was followed around by newspaper reporters looking for stories with which to satisfy the nation’s craving for a new hero in austerity Britain. They would say that they were just doing their jobs, but it was not always viewed that way by Speakman.

He did not consider himself a hero and pointed out that others, who had not received the VC, had performed the same actions in Korea. He felt uncomfortable being singled out for this special attention and hated being in the spotlight. Despite his size, he was a shy person and soon found the expectations of others difficult to live with. ‘They won’t let you be normal,’ he said at the time. ‘All the time they are watching you to see if you are getting above yourself.’ Public speaking was something he found very difficult and he shunned interviews and social occasions wherever he could. This, inevitably, led to accusations of aloofness and feelings of resentment.

Eventually, in March 1952, he decided to return to active service in Korea to escape the media attention. As a result of his reluctance to talk to the press, or even to correct inaccurate stories, errors have been perpetuated and myths have grown about how he won his VC. When he returned to Korea he would not have considered co-operating with the writing of a biography, but he has mellowed over the years and now, at 85, thinks it is time to put the record straight.

Bill Speakman is the best remembered of the four VCs awarded for Korea, but often for the wrong reasons. Many people have heard the story that he was drunk when he repelled wave after wave of Chinese soldiers with grenades and beer bottles. This is a myth; he was not drunk when he fought the enemy who were attacking his battalion’s position. It is something he has always denied and there is no evidence to support this scurrilous accusation. Speakman was a born fighter; he did not need alcohol to spur him into action and when in a fight he was unbeatable.

Since 1952 he has been known as ‘The beer bottle VC’ and it will surprise many people to learn that the story behind this is also a myth. When he ran out of grenades he is said to have thrown anything he could lay his hands on at the advancing Chinese, including rocks and beer bottles. He threw rocks but there were no beer bottles. This myth is partly based on a misquote and despite his protestations the legend persists. ‘Where would you get bottles of beer from?’ asks Speakman. ‘Whoever started the story, it seems to have caught on.’ One of the most bizarre claims made about Speakman is that when the Chinese attacked he got hold of beer bottles and hit the attackers over the head with the bottles.

Although he served in several Scottish regiments, including The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment), The King’s Own Scottish Borderers and The Royal Scots Fusiliers, William Speakman (always known as Bill) is not Scottish. His first choice of regiment was influenced by his stepfather, who had served in The Black Watch during the First World War.

He was born in Altrincham, a market town in north Cheshire 8 miles to the south-west of Manchester. Altrincham has a long history; it was originally an Anglo-Saxon settlement, meaning ‘the homestead of Aldhere’s people’, and became a chartered borough in 1290. It is interesting to note that the name of the town was spelt Altringham (which is how it is pronounced) up to about 1800 at which time the ‘c’ spelling was adopted (1). Altrincham has a population of approximately 41,000 and is now part of the Metropolitan Borough of Trafford.

Bill Speakman was born on Wednesday, 21 September 1927 into a working-class one-parent family at 17 Moss Lane, Altrincham. The area has since been redeveloped and the terraced house has been demolished. It is now the site of the Ice Ring and is on the same road as the ground of Altrincham Football Club.

THE YEAR 1927

The year 1927 was an eventful year during a decade of social and political change when both Britain and the rest of the world were still coming to terms with the aftermath of the First World War. On the day that Speakman was born, 21 September 1927, The Times reported that the Irish general election had ended inconclusively with the Government Party having a very small majority over their opponents. The political fallout from President Paul von Hindenburg’s Tannenberg Memorial speech, in which he repudiated Germany’s responsibility for the First World War, was covered in some detail. The Soviet Fleet’s Black Sea manoeuvres around Odessa were reported, as was the Air Race across the United States, which had so far claimed two lives.

He was illegitimate and is one of many men who overcame their less fortunate start in life to win the Victoria Cross. His mother, Hannah Speakman, was a ‘general servant (domestic)’ but nothing is known of his father, whose name does not appear on Speakman’s birth certificate. In an era when there was still a stigma attached to illegitimacy and little help available to single mothers, Hannah Speakman decided to keep her child. Social habits change over the years, however, and at the time of writing 47 per cent of UK births occur outside marriage. Hannah Speakman registered her son’s birth on 18 October 1927. He was named William after his maternal grandfather.

Bill Speakman never knew his father. Whoever he was, he must have been a man of means as he made regular maintenance payments to Hannah’s father to support her and her child. Speakman did not discover this until many years later. His mother never revealed the name of his father, although she had the opportunity, and to speculate on his identity would be futile. Speakman accepts the reality of the situation. ‘I am not ashamed of it because it was not my fault’, he says.

CHAPEL STREET, ALTRINCHAM

Bill Speakman was not the first war hero to come from Altrincham; during the First World War, Chapel Street, Altrincham was said to be the most patriotic street in the country. It was a short walk from Moss Lane where Speakman was born. In a street of just 60 houses, 161 men fought for King and country and 29 of them never returned. Chapel Street was in a working-class area of the town and many of the inhabitants were of Irish descent who had come to Altrincham looking for work.

In April 1919 Lord Stamford unveiled a memorial, or Roll of Honour, outside All Saints Church, Chapel Street dedicated to the local men who had helped to win the war. The names of all 161 men were recorded on the memorial and King George V sent a telegram expressing his appreciation of the sacrifices made. Chapel Street was demolished in the 1960s as part of a slum clearance programme. All Saints Church was also demolished and the glass-fronted memorial was taken into storage at Altrincham Town Hall.

In September 2009 Trafford Council erected a blue plaque honouring the 161 men who volunteered. The plaque was fixed to the wall of a restaurant in Regent Road which stands on part of the rebuilt street. Bill Speakman VC attended the plaque unveiling as a guest of the organiser, Peter Hennerley, who is a descendant of one of the Chapel Street volunteers.

Hannah Speakman had been a resident of Altrincham all her life, and was born at 4 Back Moss Lane, Altrincham on 28 December 1902. Her father, William Speakman, was born about 1867 and was the second of ten children of William and Elizabeth Speakman. He was a general labourer when Hannah was born. Her mother, Elizabeth Speakman, formerly Fowles, registered the birth on 6 February 1903. In the 1911 census, Hannah was the youngest of four children: her sisters were named Mary and Emily and her brother was Joseph. Two further sisters followed: Jessie was born in 1914 and Grace in 1916. The two older girls, Mary and Emily, had left home by the time Bill Speakman was born and he does not remember them.

At the time of her son’s birth, Hannah was in service as a general servant to the owners of one of the many large houses in the area. She was in service for one particular Bowdon family for many years; the staff were expected to work long hours for low wages. When the First World War gave women the opportunity to undertake new areas of work previously performed by men, many of them never returned to work in service. Hannah Speakman was 15 years old when the war ended so would not have had the chance to try other work and was a domestic cleaner all her life.

Max Arthur OBE noted in Symbol of Courage(2) that ‘over 75 per cent of VC awards have been made to a man who has grown up as the responsible child of an early widowed mother or the eldest child in a large family’. For almost eight years of his life, until his mother married Bert Houghton in 1935, Bill Speakman was an only child to an unmarried mother and must have learnt responsibility at an early age.

John Percival in For Valour: The Victoria Cross, Courage in Action(3) also commented on the qualities of men who were awarded the VC. He said that they all showed a strong sense of responsibility for others which they developed early in their lives.

On 15 June 1935 Hannah Speakman, aged 33, married Herbert Houghton, a 46-year-old widower, at the local register office. Herbert had previously married Lily Venables in 1919 but she died in 1928, aged 37. Herbert and Lily had two daughters: Lillian and Margaret, known as Peggy, who was born in 1926, just two years before her mother died.

The Speakman family’s home, 27 Moss Lane, is the house with the Union Flag above the door to commemorate Speakman’s homecoming in 1952. Speakman was born nearby at 17 Moss Lane. (British Pathé)

Herbert was recorded as a potato salesman living at 15 Shaw’s Road at the time of Peggy’s birth in 1926 but had become an engineers’ storekeeper by the time of his marriage to Hannah in 1935. Shaw’s Road is close to Moss Lane, so Herbert and Hannah were in the same neighbourhood and it is likely that this is how they met.

Bill Speakman was 7 years old at the time of the marriage but cannot recall the event. Houghton’s eldest daughter, Lillian, had left home by the time of her father’s remarriage. So the new family in Moss Lane was Herbert, Hannah, Peggy and Bill. Peggy was a year older than Bill and was fond of him. She later married Norman Broadbent and named her first son after Bill. Peggy died in Sheffield in 1995. Herbert and Hannah Houghton had two children: Ann Houghton, born in 1937, and Herbert Houghton, born in 1939.

Herbert Houghton senior was born in Wigan on 1 November 1888, the eldest son of William and Mary Houghton. Herbert was the eldest of three children; his siblings were William and Annie. Prior to his service during the First World War, he was employed as a railway clerk, in the engineers’ department, and lived at Linwood Terrace, 13 Stockport Road, Altrincham. He enlisted, as a volunteer, in The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) on 17 November 1915 and was posted to the 2nd Battalion, then serving in Mesopotamia (now Iraq) (4). He joined the battalion, via India, in June 1916.

Houghton’s health soon suffered as a result of the climate and conditions in Mesopotamia, and he contracted malaria and dysentery. He was evacuated to India, where he spent several months in hospital. Although he returned to Mesopotamia in June 1917, he suffered further ill health and was again invalided to India to recover. He spent a total of one year and 227 days in India and just 127 days in Mesopotamia.

Houghton was invalided to England in February 1918 and, after attachments in England and Ireland with other Black Watch battalions, arrived in France just before the end of the war. However, his health had not improved and he developed pleurisy in November 1918 and was admitted to hospital in France. He was discharged from the Army in March 1919, and his poor health later contributed to his death at the relatively early age of 60. Houghton was said to have been gassed during the First World War, but there is nothing in his extensive medical records to confirm this.

THE BLACK WATCH

The regiment began its history in 1725 as a number of independent companies to patrol, or ‘watch’, the Highlands for smugglers. Through amalgamation of these companies, the 43rd (Highland) Regiment of Foot was formed in 1739. The new regiment was renumbered the 42nd Regiment twelve years later, and in the 1881 reorganisation became known as The Black Watch (Royal Highlanders). In 1920 the name was changed again, to The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment). After amalgamations of Scottish infantry regiments in 2006, the regiment became The Black Watch, 3rd Battalion Royal Regiment of Scotland.

The regiment has served all over the world and fourteen men serving in The Black Watch or its predecessors have been awarded the Victoria Cross (eight of them for the Indian Mutiny).

Speakman got on well with his stepfather, who he remembers as ‘a short, stocky man’, and when he was old enough he joined Bert’s old regiment:

I wanted to join the Army from an early age because my stepfather was in The Black Watch and was gassed in the trenches in the First World War. So he brought his gear with him, including his kilt. They used to have an apron when they went in the trenches to keep it clean and his shoes, apron and tackle were stored in the bottom cupboard. I used to sit on that cupboard and go through his collection of badges. In those days if you had a Black Watch badge you could take it to pieces and put it back together again.

Bert was a good stepfather. Bit tough at times, but then again that was the way it was. He was very grumpy at times because he was gassed in the First World War. Later on he often used to sleep downstairs. He couldn’t always make the stairs because of his coughing. He always used to smoke a pipe which didn’t help.