Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

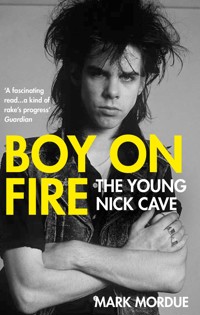

An intensely beautiful, profound and poetic biography of the formative years of the dark prince of rock 'n' roll, Boy on Fire is Nick Cave's creation story, a portrait of the artist first as a boy, then as a young man. A deeply insightful work which charts his family, friends, influences, milieu and, most of all, his music, it reveals how Nick Cave shaped himself into the extraordinary artist he would become. A powerful account of a singular, uncompromising artist, Boy on Fire is also a vivid and evocative rendering of a time and place, from the fast-running dark rivers and ghost gums of country-town Australia to the torn wallpaper, sticky carpet and manic energy of the nascent punk scene which hit staid 1970s Melbourne like an atom bomb. Boy on Fire is a stunning biographical achievement.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 637

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Mark Mordue is an Australian writer, journalist and editor. He is a co-winner of the 2014 Peter Blazey Fellowship, which recognises the development of an outstanding manuscript in the fields of biography, autobiography or life writing. He is the author of the acclaimed poetry collection Darlinghurst Funeral Rites and the memoir Dastgah: Diary of a Headtrip. His journalism has been published in Rolling Stone, Vogue, GQ, Interview, the Australian and the Sydney Morning Herald. He was the winner of a 1992 Human Rights Media Award and the 2010 Pascall Prize for Australian ‘Critic of the Year’. His poetry was shortlisted for the 2016 WB Yeats Poetry Prize and, together with his fiction, essays and memoir work, has appeared in literary journals including HEAT, Meanjin, Griffith Review and Overland. He lives in Sydney.

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Allen & Unwin

First published in Australia in 2020 by HarperCollinsPublishers

Australia Pty Limited

Copyright © Mark Mordue, 2020

The moral right of Mark Mordue to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders.The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Allen & Unwin

c/o Atlantic Books

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Phone: 020 7269 1610

Fax: 020 7430 0916

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Photographs by Peter Milne appear courtesy of Peter Milne and M.33, Melbourne

Typeset in Bembo Std by Kelli Lonergan

Hardback ISBN 978 1 83895 369 0

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 83895 370 6

E-Book ISBN 978 1 83895 371 3

Printed in

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my children,

Atticus, Franny and Levon

And for Bryan Wellington,

Anne Shannon and Eddie Baumgarten,and all the boys and girls next door

‘At the end of it all, it was difficult to decide which was the more romantic, the more exciting: the real man or the myth he has become.’

Colin F Cave, Ned Kelly: Man and Myth

Nick Cave singing ‘I’m Eighteen’, Boys Next Door gig, Swinburne College, 1977 (Peter Milne)

CONTENTS

Author’s Note

Prologue: The Journalist and the Singer

Part I: The Rider

Such Is Life

King and Country

Part II: The Good Son

Man in the Moon

Down by the River

Part III: Sonny’s Burning

The Word

Double Trouble

Zoo Music Girl

Boy Hero

Part IV: God’s Hotel

Shivers

Flight from Death

Crime and Punishment

Epilogue: The Singer and the Song

Acknowledgements

Endnotes

Selected Bibliography

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Quotes by Nick Cave are from interviews and phone conversations between us from 2010 to 2018. These are used throughout the text – and without endnotes – unless additional context is required.

Interviews that occurred earlier with me over the course of Nick Cave’s career – and published stories of mine about him and his work – are referenced in the endnotes and acknowledgements.

Interviews I carried out with Nick Cave’s family, friends and peers – along with material drawn from books, essays, articles and reviews, and Nick Cave’s own journals, notebooks and letters archived at The Arts Centre, Melbourne – are referenced in endnotes.

In areas where published material and my own interviews overlap, I have chosen the more articulate version, and delineated between a published quote and an elaboration based on my own conversations. This was made easier by well-worn anecdotes, even the verbatim retelling of certain events.

I have tried to be wary of entrenched perceptions – and their opposite, the elision or rewriting of history, in content or emotion, to fit with a new point of view. Certain truths, even ‘facts’, remain in the province of the group more than the individual. History is still alive to those who lived it.

Un pour tous, tous pour un

One for all, and all for one.

PROLOGUE

TheJournalistand theSinger

The first time I ever spoke to Nick Cave was in a phone interview to promote his second solo album, The Firstborn Is Dead (1985), an ominous, blues-affected work that sanctified the birth of Elvis Presley and thereby rock ’n’ roll itself in quasi-religious, apocalyptic terms. Our conversation around the recording was as dry as spinifex, so slow and spacious it sometimes ceased to exist. As if Cave could not be less interested in what I was asking or saying and never would be. Given his notorious hatred of journalists back then, this made for an uphill experience. I put the phone down with sweating palms and a sinking feeling in my heart. What a failure.

Dealing with Cave again, let alone meeting him in person, was not something I looked forward to. In 1988 I nonetheless lobbied to interview Nick Cave for Sydney’s On the Street. Second time lucky, I must have been hoping. Face to face he had to be more approachable than that distant voice on an echoing telephone line. Besides, he was the pre-eminent Australian rock ’n’ roll artist of his day. This made him hard to ignore.

Cave was in town to read from and preview a much anticipated literary work in progress, a book that would become known as And the Ass Saw the Angel (1989). He’d already gone so far as to declare himself ‘more of a writer now’1, disowning rock ’n’ roll for its lowbrow qualities and Pavlov’s-dog audience responses.2

I was given a laneway address for a warehouse located directly behind Sydney’s somewhat alternative and bohemian gay strip, Oxford Street. Cave was apparently holed up there with a girlfriend or a dealer or criminal acquaintance: rumours varied, depending who I spoke to. As always with Cave, rumours were all around him, as if his every movement across town were hot-wired into the gossip chambers of inner-city Sydney conversation. The only other wave-making machine of this kind that I would ever know was Michael Hutchence. It was as if you could feel their presence rippling through the city from the moment their flight hit the tarmac and they entered, half in secret, into our closed little world.

When I knocked on the door of what looked like an old garage, a key was hurled to the road with a vaguely familiar shout hovering invisibly on the Sunday-afternoon air. As I let myself in, I heard footsteps on the wooden ceiling and the creak of a trapdoor above. At the top of the ladder-like stairs that rolled down to meet me with a thud there was now a hole in the ceiling where Nick Cave himself stood, bathed in backlight. He beckoned me upwards like some awful figure in a B-grade horror film about a journalist come to interview a terrifying rock ’n’ roll vampire. I gulped and set forth on my way to meet my Nosferatu.

Once I arrived upstairs, the atmosphere changed immediately. Cave was a solicitous host, while a young woman I took to be his partner bossed him about as if I had just entered a Goth version of the British comedy George and Mildred. ‘Get Mark something to eat, Nick,’ she said briskly. A large serving of the very best fruits was put before me – grapes, lychees, melon, apple – all prepared and presented in a grand manner.

As Cave was about to seat himself and enjoy some of this banquet, his partner said, ‘Did you offer Mark some coffee, Nick?’ Again he rose, mock lugubrious, stick-insect angular. He went over to an old metal funnel attached to a wooden workbench, poured in some coffee beans and began to slowly turn a handle: ‘Grind, grind, grind, it’s the story of my life.’

With a variety of expensive biscuits now also arrayed before me, I was soon thanking the couple for their surprising hospitality. Cave asked me why it should be so unexpected. An evasive answer seemed tactically unwise, so I mentioned the Prince of Darkness thing around him, and his reputation for treating journalists poorly. ‘Who says that?’ he asked, a little surly. ‘Why, the NME [New Musical Express] …’ I began to say, in reference to the influential British music paper of the day. ‘The NME!’ he barked. Cave began to grind the coffee beans with much greater intensity. His partner looked at me and said, ‘Don’t get him started.’ To Cave she called out in a calming voice, ‘Now, Nick …’ Cave ground on, taking it out on the beans: ‘The NME!’

Finally he came back over to us with a large silver coffee pot steaming with his efforts. A set of fine china cups were ready on a matching silver serving tray. Mid-pour, Cave lost focus, the coffee slowly streaming out of the spout and around – but not into – the cups in an ever-widening circle, the tray filling with black liquid as if it were a swimming pool, until he snapped back into consciousness and finally found the cups as well. Completing the task at last, Cave then asked me with all the decorum he could muster: ‘Would you like milk or sugar with that?’

The next two and a half hours felt rather like an interview taking place under similarly dark water. Each question seemed to demand huge reservoirs of concentration from Cave, not to mention frequent pauses and micro-sleeps. Cave’s sometimes thin and creaky, sometimes sonorous and self-consciously refined speaking voice certainly had its hypnotic qualities. I felt suspended, unsure of what to do, or even how to leave. To be honest, I’m not sure the encounter ever quite ended so much as faded away. With everyone heavily relaxed, I departed once more through the floor.

It was yet another Cave interview in which I felt I had somehow failed, despite Cave’s very best efforts to help me. This was largely because I didn’t really understand how to write up what had happened. I also dreaded sitting down and transcribing the interview tapes, a process that would demand even greater leagues of passing time from me all over again.

Two nights later, on stage at the Mandolin Cinema in Sydney’s Surry Hills, Cave would recite from sections of his work in progress while an ambient soundtrack rose and fell with suitably ominous and dreamlike effect around his reading voice.3 Looking every inch the ‘Black Crow King’ (one of many self-referential character songs that would add to his mythology, despite the satirical swipes it took at his image and those who subscribed to it), Cave did not so much walk onto the stage as dangle, stoop and hang in the air as if from unseen strings. He would eventually fall off the stage. And yet the cinema was full to the brim with his fans, a sellout performance over two nights, and a success in terms of the mood created by him reading from what appeared to be a credible, black-humoured, Faulknerian work of fiction well on the way to completion.

In 1994, six years after these readings and our warehouse encounter, the boot would be on the other foot, when I once again spoke to Cave, this time over the phone. He’d been living in São Paulo, Brazil, and – by all public accounts at least – was as clean as a whistle. For me it was an early-morning interview. Very early. Unfortunately, I’d broken up with my girlfriend the previous night and not been home, to sleep or otherwise, barely brushing in the door to take Cave’s call. Thank God I’d prepared the previous day. When Cave asked me how I was, I told him at great length: that I’d been out wandering all night, that I’d been here and there, felt this and thought that, a long, wild, emotional ramble that ended with me saying I loved his new record, Let Love In, and finally asking if he had a favourite walk he liked to take in São Paulo.

Cave took this all in with a long pause and slight grunt – and we began to talk. It was a great interview and I liked him a lot. He seemed completely non-judgemental about my ‘condition’; in fact, I’d say he was both courteous and curiously amused throughout. As for his answer to my opening question: ‘Well, I make my favourite walk daily. Which is up to my local bar. Out the door, up the street, past the junkyard where the chickens and the old junkyard dog sits. And up a steep hill to my favourite bar, San Pedro’s. There’s this giant barman there who is the fattest guy I’ve ever seen. He is constantly described by locals as a huge woman, but he’s a man with a moustache. He looks more like a giant baby to me. I sit there and read, drink and contemplate the meaning of life. Then I walk back down.’4

A few years on I would meet Cave again, in 1997 in a rather sterile, fluorescent-lit room at the offices of Festival Mushroom in Sydney. Cave remembered me well enough, but his mood was odd and, I realise now, highly vulnerable, as The Boatman’s Call – a raw and revealing album that revolved around his break-up with Brazilian partner Viviane Carneiro and a wounding affair with PJ Harvey – was about to be released. None of that was public knowledge yet. I nonetheless asked him, almost randomly, if he thought the love of a good woman could redeem a man. It was a question that seemed to arise out of his lyrics and what they implied across the record. Cave looked at me as if I were a total fucking idiot, and then away at the white wall as if he were a hopeless and godforsaken case himself. ‘How the hell would I know?’ he said. And then he looked back at me and waited for the next question.

More than a decade after that last experience, I began work on a biography of Nick Cave’s life. Biographies are strange beasts, underlined by a cautionary wisdom that dates back to artists of the Italian Renaissance and their understanding that the portrait painter always paints something of his or her self.5

Nick and I met to discuss the project at his Brighton and Hove home office in the United Kingdom in 2010. I was told he could give me a few hours. We would spend the next three days talking intensely, then speak often in person after that, as well as on the phone, on tour and via email over the years to come. I still remember that first meeting outside his office, a very warm day. We were so close to the beach I could hear the waves washing back and forth over the stones. I had on a new pair of Havaianas branded as ‘Brazilian blue’, a good-luck purchase for my opening encounter. Nick noticed them immediately. ‘Great colour! Mine are pink. I will wear them tomorrow.’

He was bright as a button, his office charged with creative energy and an apparent zeal that year for the works of American poets John Berryman and Frederick Seidel. Later, I would become intrigued by Berryman’s sense of multiple selves and his use of them to create a performance on the page, interrogating himself through actors that were variations of his own personality. Seidel was very different: commanding and privileged, savage and song-like as he moved through his world. It was not hard to understand why these voices appealed to Nick. He encouraged me to investigate Jerome Rothenberg, whose collection Technicians of the Sacred had become a foundational text for him. It gathered together a global array of shamanistic ritual songs and chants and their contemporary equivalents. The radical leaps in logic, the sense of magic at work, the veneration of sound (over language itself) as a form of meaning or feeling – all resonate in everything that came along from Push the Sky Away onwards. As I write, I can see how Rothenberg’s work changed Nick’s thinking about music as much as lyrics, affecting the spiritual journey he would go on to make Ghosteen with Warren Ellis and the rest of The Bad Seeds.

On the second day of our meetings in Brighton, we went upstairs to Nick’s family home, a rare act of trust. While Nick was answering phone calls, his wife, Susie Bick, asked if I was hungry. She made me a sandwich for lunch, then offered me tea and biscuits she scrabbled to find in their fridge. Susie had an aristocratic, almost nervous, energy that struck me as eccentric and vulnerable and wild, not quite of this earth. Something about Susie finding those extra biscuits for me felt particularly kind and thoughtful. And though she did not want to be interviewed for the biography, I liked her from that moment on for making me feel so welcome in her home, where others may have been more defensive or suspicious.

Nick told me later that Susie had a habit of moving the furniture around. He would return from a visit to London or a tour, even just a night out, and not be able to find the lounge and the television. ‘Sometimes she’s moved the entire bedroom to another room and I can’t find that either.’ He seemed to accept this with a shrug. ‘I’ve mentioned it in song. People think it’s some poetic image I’ve made up. I’m just documenting a straight fact.’

There was a guy downstairs whom Nick had recently helped clear out some space. ‘He was like those people you see on TV shows about hoarding.’ It had been almost impossible to get inside his apartment. The debris had begun to collect outside in the hall. Nick felt a sense of achievement when he convinced him to surrender a number of old and rusty pushbikes, as well as the more general rubbish he’d accumulated. It was all a matter of giving the poor fellow encouragement. ‘I told him, “C’mon, you can do it.”’ Nick laughed. ‘I know he will collect the same kind of stuff and it will all just come back in the door and I will have to do the whole thing again a year from now.’

Perhaps fame necessitated the same house clearing. I would see how forcefully some people sought to attach themselves to Nick, as well as how wounded and resentful those left behind could feel. I set my own terms of intimacy and distance as best I could, embarrassed by the way people would disempower, even disenfranchise themselves, just to be in his company.

As a biographer, I came to define the cloudy territory I found myself in as akin to a working friendship. I understood that when the work was over, the friendship would likely pass. This was the dilemma Nick left behind for people as their life story got sucked up into the slipstream of his, forever measured against his adventure and the songs that marked it. I vowed to avoid this fatal attachment. Though, of course, as you get to know people over time, things are never so straightforward. The act of maintaining a little distance can be confusing, perhaps even two-faced. So too can opening up.

On the third day of our meetings, the end of a school day, Nick and I went out for pizza with his ten-year-old twin sons, Arthur and Earl. Like many fathers who worked from home, Nick struck me as attentive and involved with his children, and very close to them, a good father. Earl seemed quieter and shyer, nearer to Susie in his tender demeanour. Although Arthur was fair in his looks, he took more after Nick and was robustly social. He was interested in magic and a bit of a performer. Arthur had an impressive rope trick he could do. Even when he showed me how he had managed the finale, a dramatic and quick untangling, I still could not work out how he had done it. Arthur tried to show me again a few times and I failed to see the revelation each time he explained it. Eventually, Nick waved his hand at him to stop him and said, ‘I think your secret is safe here in England, Arthur. Mark won’t be able to take the rope trick back to Australia with him.’

By the summer of 2013, I was deep into the biography. Nick and I met in Melbourne at his mother Dawn’s house. It was twilight and we walked with his sons to a nearby park. The boys shared a skateboard and what looked like a very good digital film camera. I was under the impression Earl was more accomplished on the skateboard, but it was Arthur who rode it slowly inside and around a hazily lit park rotunda while Earl climbed onto railings and filmed him. Nick called out to be careful. They explained they wanted to avoid showing the skateboard, to create the illusion that Arthur was floating like a bird or someone in a dream.

The loss of fifteen-year-old Arthur from a cliff fall on 14 July 2015 was a terrible tragedy for Nick and Susie and Earl and all the extended Cave family. By then my biography project had long unravelled as the quantity, quality and depth of Nick Cave’s output overwhelmed me. What I had started writing became a baggy and unfinished monster with all the scope and cornucopia of Moby Dick. My idea for its form had involved conventional chronology and the nine lives of a cat, but also a symbolic under-structure pinned to Milton’s Paradise Lost, a work Nick had referenced repeatedly with allusions to ‘the red hand’ of God.6 I could see many easy parallels: God casts the rebellious Satan out of Heaven (Nick is banished by his father from his country home of Wangaratta); the Fallen Angel gathers his demonic cohorts to build Pandemonium (Nick meets the members of The Boys Next Door and they forge themselves at the Crystal Ballroom in St Kilda); Satan travels across space to wreak revenge on Eden (Nick travels to England to begin his assault on the garden of culture) … Such connections were loose and incidental, but also well mapped in song, as if Nick had been writing and reinforcing his own mythology all the way. Which, of course, he had.

After the death of Arthur, Nick felt he had been changed entirely. There was only before and after. ‘I’m a different person now,’ he said to me on a few occasions. In his opinion, this rendered what had been said in our conversations ‘entirely redundant’.

Our communications dissipated and ceased. I occupied myself with my own struggles and life story, a messy and tangled narrative all its own as, by then, my grand Miltonian plans for a Nick Cave mega-biography had well and truly collapsed. I must say Nick was only ever kind and understanding over the period when I went off the rails, expressing concern for my wellbeing and encouraging me to rebuild myself, as well as offering good-humoured conversation and a few spikes of pragmatism. But the road we were on was parting, as I always knew it would. The ride was over.

I lamented that I nonetheless did have a biographical volume almost done, a portrait of the artist as a young man and all that he promised ahead of him. A book that, with just a bit more work, was even more important in the wake of what had occurred. This book keyed itself in to Nick Cave’s childhood and youth, from Wangaratta to the Crystal Ballroom scene in Melbourne, through the early landscapes, novels, artists, loves and friendships that shaped him. Much of which Nick would continually refer to in his songs, books, poetry and films. I believe this Australian youth, this Australian being, to run deep inside him. I also believe it relates to something paradoxical about the nature of ‘Australianness’ itself: how we undervalue and disguise, and even dismiss what we are as we look outward from our culture for international affirmations, losing sight of our history in a sometimes brutal and ongoing act of forgetting. The older we get, however, the more we begin to reach back to our youth as essential to who we are and who we still can be.

What emerges in this biography is a remembering of that world. Not just Nick Cave’s story of growing up, but the memories and stories of all those around him. The life and times of a boy on fire, with all that he absorbed in order to dream himself into becoming one of the darkest, and then one of the brightest, of our rock ’n’ roll stars. Light enough for the many to share.

Nick Cave backstage at the Tiger Lounge, Royal Oak Hotel, Richmond, 1978 (Phill Calvert)

PART I

THERIDER

SuchIs Life

MELBOURNE & SYDNEY 2007

‘Too little, too late,’ he says. Nicholas Edward Cave has just turned fifty, and old wheels are grinding inside him.1 His car pulls forward at the traffic lights and makes its way further down his former stomping ground, Fitzroy Street, St Kilda. The silvery light of an encroaching Melbourne dusk settles over the peak-hour traffic and he catches a glimpse of the waters of Port Phillip Bay at the street’s bottom end, as if he could drive into this same silvering and disappear.

It is 28 October 2007 and Nick Cave is about to fly to Sydney to be inducted into the ARIA (Australian Record Industry Association) Hall of Fame. The singer describes it as ‘the seventh circle of hell’, then ‘a bad party you can never escape. Let’s face it, it’s really a form of punishment.’2 For a moment he considers stopping the vehicle so he can hop out on Fitzroy Street and run away. The ARIA Awards! He puts his head to the glass as if he has a headache. Thump. ‘God, I’d rather just go and get a kebab.’3

The only people he’d care to associate with in this Oz Rock Valhalla to which he is being condemned are The Saints and AC/DC, he reckons. There’s Michael Hutchence too, of course, ‘a beautiful guy’, but Cave’s friendship with him was not about halls of fame or even music, not INXS anyway; that was quietly understood. There was something else between them. Something brotherly only people in their shoes could share. Those stoned afternoons they’d spent trying to pull their lives together as well as having fun. Mornings when the pair would take their respective son and daughter, Luke and Tiger Lily, to a local park. The Portobello Café, which they bought together in London in 1995; that place never made a profit. The phone messages Michael left him two years later, so wild and funny, and in retrospect so in need of contact. Michael’s voice on his answering machine saying, ‘I’m coming to see The Bad Seeds play in Sydney, Nick. I’ll be up the front throwing rotten fruit at you.’4 Nick still has the hotel number jotted down in an old diary somewhere, along with a note to call Michael back in Sydney.5 ‘Ask for Murray River’s room,’ Hutchence said with a laugh.6

November 1997. Ten years earlier. What a bad month that was. Beginning with Kevin ‘Epic Soundtracks’ Godfrey – the former drummer for Swell Maps, Crime and the City Solution, and These Immortal Souls – turning out the lights in his West Hampstead flat and never waking up. Nick can only shrug when Epic’s name comes up. He didn’t know him that well. ‘And to tell you the truth, I was never a big fan of his music, but people I rated always rated him, so I had to respect that.’ Epic died in his sleep, cocaine and heroin in his system, autopsy results inconclusive. The information would reach Nick through mutual friends, including his Bad Seeds collaborator and bandmate Mick Harvey and the singer Dave Graney, both of whom were troubled by Epic’s death and what could have been a decision or plain bad luck.

A few weeks later Michael Hutchence passed away at a five-star hotel in Double Bay, Sydney, under similarly cloudy circumstances. Ten years ago, almost to the day. Nick ended up writing out a set of lyrics when he got the news: ‘Adieu, adieu, kind friends adieu, I can no longer stay with you …’ The words were drawn from an eighteenth-century west-country English ballad called ‘There Is a Tavern in the Town’: the lament of a suicidal woman destroyed by her lover’s insensitivity. It is also known in some quarters as ‘The Drunkard’s Song’. In Nick’s diary version, various lines are reworked as the narrator’s voice slips uneasily between a method actor’s empathy for what is happening and a storyteller’s detached insights.7

Looking from the outside, who’d have thought Nick would have been the good influence in this friendship, the one who learned to swim while Michael was going under? ‘I liked Michael a lot. He was very passionate. There was a truth to Michael that was very impressive. When I knew him he was going through a really bad period, being hounded night and day by the English press. He couldn’t move a muscle. I didn’t understand the extent of it till we went out to this club together. We got in fine. But when we left there were paparazzi everywhere. Someone pushed me. In a rage I pushed them back. Michael pulled me away. Then we left. He said to me, “You can’t do that, it’s a waste of time.” It was criminal what they did to Michael. They hunted that guy to his death.’

These weren’t the first or last people Nick would witness leaving this world unexpectedly. Not by a long shot. Ever since his father, Colin Cave, was killed in a car crash, he had been learning what it meant to live with the dead. The road accident happened on the first Sunday of 1979, just a few months after Nick turned twenty-one. It took him a long time to accept how much it affected him, Nick says, ‘to engage with it or even understand it’. Between his mother’s pain and the thrill of leaving for London a year later, in February 1980, with his fine young band, The Boys Next Door, Nick had pushed his own feelings aside. He only saw later how the loss of his father intensified something that went back to his boyhood days in Wangaratta. Not even the town as it was, really, more the way he would remember it and then mythologise it. Things like the railroad tracks, the slaughterhouse, the river where he swam and its willow trees had become the stuff of songs such as ‘Red Right Hand’ and ‘Sad Waters’ for him, a real and yet imaginatively transformed land akin to William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County.8

As if to confirm a rural Gothic streak straight out of a novel by the likes of Faulkner or Flannery O’Connor, Nick had even found a body when he was a kid. Someone from the old people’s home had stumbled down in their pyjamas to the shade of the riverbank and lain down to sleep in the mud. For the twelve-year-old Nick and his friends it had been the thrill of their day, astride their bikes on a narrow strip of road staring down at the still figure. Amid their excited chatter, one of the boys silenced everyone. ‘“Show some respect for a dead man,” he said. I really remember that.’ Nick could not wait to get home and tell his mother about their discovery. ‘She wasn’t very happy with the way the police had spoken to us, actually. They told us all to piss off when they arrived.’

Nick Cave’s old friend, photographer and journalist Bleddyn Butcher, is driving him to the airport in Melbourne today so Nick can get to the ARIAs on time. Bleddyn’s black suit and bolo tie accentuate a bright face and bob of unruly white hair that faintly suggest the appearance of a frontier-town Tennessee judge. An exceptionally long fingernail on the pinky of Bleddyn’s right hand serves him well for playing guitar at home; it has Oriental overtones too, symbolising a man of culture and breeding who is above manual labour. In Taxi Driver, a much-loved film of Nick’s teenage years, Harvey Keitel’s pimp character has a similarly long talon, painted red and used for the convenience of sniffing heroin on the go.

A figure of almost enraged intelligence, Butcher is made of more affectionate materials than such associations might indicate. ‘I think I can call Nick a friend,’ he tells me later, touching his chest. ‘I think so. I feel it in my heart.’9 Having photographed Nick for the NME ever since the singer’s arrival in London with The Birthday Party in 1980, and run an official Nick Cave fanzine called The Witness in the late 1990s, the London-born, Perth-raised Butcher can lay claim to knowing Nick’s work as well as anyone. Unlike many in Nick’s orbit, he’s never shy of making his judgements, or his appreciations, known, something that moves Cave to drolly comment, ‘You don’t go to Bleddyn for a response when you have something at a sensitive stage of development.’

Even so, here Bleddyn Butcher is, back in Melbourne and driving ‘The Dark Lord’ (as he likes to call Nick) around again. It amuses him that the singer did not apply for a learner’s permit till 2001 in the United Kingdom, which is where Cave continues to reside today, in the seaside community of Brighton and Hove. The driver’s licence might be interpreted as yet another marker of Nick’s drug-free lifestyle. Let’s face it, the 1980s was not a time when you wanted to see The Dark Lord behind the wheel of any vehicle coming your way. Bleddyn can only arch an eyebrow and observe, ‘Nick is still a little prone to lose focus behind the wheel if he’s talking to you.’10

Bleddyn has picked Nick up from his mother’s place, where he sat around over tea and homemade cheese scones with Dawn Cave while her son packed his bags. The sparring intelligence between mother and son has the light touch of comedy: Nick’s lugubrious, ‘Yes, Mum’; Dawn’s wry comebacks; the jolts of affection that unite them and pull you closer to them when they are together. It is surprising to Bleddyn, but there is one word that is rather underused in critical appreciations of Nick’s work, yet is present throughout a host of his songs, and in the way he sings them: tenderness.

Dawn Cave’s present happiness is a matter of long-term relief as much as anything else. After all the years of turbulence, her son ‘has settled down so well’ with his wife, Susie, an English former model and Vivienne Westwood fashion muse. ‘And he’s such a good father to the twins, Arthur and Earl. If Nick’s father, Colin, were alive today he’d be so proud,’ she says later in an interview. ‘And Nick’s free of the drugs, too.’ Dawn holds her hands together in an unconscious prayer motion as she contemplates it. Being with Susie made all the difference in the end: ‘They saved each other, I think. I could have run down the street and jumped up and kicked my heels together, I was that relieved and happy when Nick first told me he was going into rehab. Little did I know how hard it would be, how long it would take, but I will always remember that first time [in 1988]. At last, I thought, at last.’ 11 Ten years on, and four more rehab centres later, Susie Bick finally came onto the scene. At last, at last.

Dawn waved goodbye to Nick and Bleddyn from the door of her home and closed the security grille. Nick had told her the night before that a few old friends were ribbing him about an exhibition of his life and work coming up in Melbourne, entitled, appropriately enough – ‘and with all due humility!’ he says – Nick Cave: The Exhibition.12 Pennants showing his face are already fluttering from flagpoles around The Arts Centre in the heart of the city to promote the show, which opens in another week. Together with the 2007 ARIA Hall of Fame induction this evening, it contributes to a rather uncool impression that this one-time punk rocker and wild man of Australian rock ’n’ roll is being institutionalised and tamed.

The putdowns are endless, a few quite barbed. Nick’s exgirlfriend and first great muse, Anita Lane, will be there with the others on opening night, going through room after room, heckling him and comparing Nick Cave: The Exhibition to a game of Where’s Wally?

Anita Lane. She always had a way of shaking Nick out of himself. Old friends sometimes refer to her as ‘his first wife’. You can barely see the scar she left on Nick Cave’s face two decades ago. He touches it, almost without thinking, as he sits in traffic and Bleddyn edges their vehicle forward. Fitzroy Street in St Kilda makes him think of her, especially with the night coming on. It’s where their adventures began in the late 1970s, with art and music, with heroin too, and a whole way of being that carried on across the world, to London, then West Berlin and a few other cities as well. On the cover of Tender Prey (1988), the scar looks as fresh as a rapier slash from a duel. It was a vegetable knife, prosaically enough, a middle-of-the-day domestic in West Berlin during which Anita took a chunk out of his cheek and went at him for another piece. Nick had unwisely decided to end their relationship once and for all by telling her that he had a new girlfriend. The relationship would recover, sputtering on for another year.

Amphetamines could do that to you back then. The drugs flowing from the East were very high-grade. Speed addictions would send half the city mad, leaving people damaged and broken just as the Wall was falling and Germany was being reunited. Nick would hear the crowds shouting in the streets while he and The Bad Seeds were working at Hansa Studios on the night of 9 November 1989. He would not allow the band to leave the studio to take a look, relenting only to let them watch the television news. In truth, the band were not that interested. Like many West Berliners they anticipated people from the East bringing down the tone of their neighbourhood, breaking through the Wall and singing about freedom – yeah, sure – but mostly screaming out for stonewash denim, Coca Cola and ‘buying bananas’, Nick says. For him it was time to finish the album – and get out of town permanently. Owing money to various dealers only added to his motivation to leave while everything was falling down.

Ever since Nick had left Australia, he had lived in a wilful state of exile, and more than a little like a man on the run. Having used up Melbourne, London and West Berlin, he’d made the city of São Paulo, in Brazil, his next port of call after coming out of a legally enforced stint of rehab for the first time in England. On a tour of Brazil at the end of 1988 he’d met a new lover, Viviane Carneiro, and found fresh inspiration in the culture he encountered there. Brazil had quickly become his new home and marked a new direction in his music. The Good Son had been recorded there, and he’d only skulked back into West Berlin in late 1989 to finish the sound mixes at Hansa, his drug debts and the temptation to relapse with friends making it a necessarily brief return.

Fleeing back to Brazil was what old hands in NA and AA referred to as ‘doing a geographic’ – running elsewhere, only to discover you took your problems with you. He wrote ‘The Ship Song’ not long after coming out of rehab, farewelling Anita and longing for what Viviane and a new world promised. After enjoying a celebrity welcome to Brazil, Nick thought he liked the day-to-day of being ‘nothing but a gringo’ in São Paulo. But even outsiders can get tired of things. He was never that great with foreign languages. Viviane felt that Nick’s dependency on her to speak for him drained him of his enthusiasm for her country.13 That and the fact he was drinking like a fish, the classic ex-junkie way to self-medicate. Nick tried New York as an alternative base, but it was too crazy there to set up a family. São Paulo, West Berlin, São Paulo, New York, London, São Paulo, London again, then back to São Paulo … it was getting hard to keep track of where Nick lived. He made firmer plans to relocate to England, and Viviane, now his wife, and their young son, Luke, followed him to try to make another home together.

Back more or less living in London by 1993, and much the worse for wear from drinking and drugging again, Nick found himself being interviewed by MTV Europe in a bar. Sitting beside him was The Pogues’ sacked singer, Shane MacGowan, perhaps the most famous booze-hound in rock ’n’ roll since the early days of Tom Waits. Nick and Shane had put together a Christmas song the previous year, a sincere version of Louis Armstrong’s ‘What a Wonderful World’ that swam out of their shipwrecked reputations. Many critics found it hard to distinguish its pained idealism from drunken karaoke. MacGowan’s profoundly Irish music had made Nick aware of a great loss in his own life – and the lost horizon he felt was lurking below their interpretation of ‘What a Wonderful World’. ‘The older I get,’ Nick told MTV, ‘the more inclined I am to think that you need some kind of roots and you need to think that you belong somewhere … I’ve kind of destroyed that part of me as a person. I really don’t feel I do belong anywhere anymore.’14 It was a sad confession to make on camera. But Nick was bullshitting himself. He was always going to have to answer to home sooner or later. Or if not quite home exactly, the gravitational pull of a past he’d yearn for in his songs and buck against in his life as if there were something way back in time to be ashamed of.

Home. There were days when Nick had ‘this awful intuition of Melbourne’ looming over him. When it felt as if everybody was trying to own him and ‘any sign of me enjoying success is construed as me getting too big for my boots’. It makes coming back to Australia hard, even a little suffocating. It is not so far away from the ideas he played with in the old Birthday Party song ‘Sonny’s Burning’. Crime and punishment in his work were as ambiguous as the sadomasochistic twist to his heart in those days. ‘Sonny’s Burning’ enhanced the demonic sexual presence glowing around him in 1982, irradiated in the song by repressed desires that consume him. The narrative positioned the listener as complicit in a torture scenario, enjoying the warmth and light that comes from burning Sonny alive. Birthday Party performances would be incited by a ritual shout-out before it began: ‘Hands up who wants to die?!’15

Though he played the seductive predator in the song, a carny-like presenter of a sinister peepshow, Nick was slyly sanctifying himself as the victim of an audience revelling in his self-destructive impulses. Twenty-five years later and here he is, no longer destroying himself, which seems to invite greater resentment from some quarters. His crimes in 2007 are health and happiness; his punishment delivered by friends who once supported him. Susie chides Nick for putting up with their snide comments at the Melbourne social events they are invited to: ‘Why do you bother with these people when they behave this way towards you?’ Nick is unusually silent and unable to answer. But he definitely broods on it. Friends of a world he had left behind.

As Nick left his mother’s house for the ARIA Hall of Fame induction, Dawn sensed his troubled mood and pulled him aside to give him a tight hug and a pat on the back. ‘Hold your head up high, Nick,’ she told him, ‘and fuck them all!’

Nick Cave laughs in the car about what he describes as his then 81-year-old mother’s ‘sage advice’. She’s a retired librarian, and it’s not her usual manner of speaking. He’ll pocket it away for future reference, ‘a maxim to keep in mind’, even tell Dawn later, to her horror, that he is thinking of getting it translated into Latin and put on a family coat of arms in England. Fuck them all! He wishes he had it emblazoned on a T-shirt right now – Fuck lemma totus? That isn’t quite right. If his old friend, the Boys Next Door and Birthday Party bassist, Tracy Pew, were alive, he’d translate it in a snap – and probably come up with a suitably ribald T-shirt design as well.

An epileptic fit killed Tracy Pew on 7 November 1986. Nick thinks that after years of heavy drinking Tracy’s sobriety may have brought on the seizures that eventually ended his life at age twenty-eight. ‘I don’t know that for sure, but it can happen,’ says Nick, like he does know. It was yet another event that made the month of November chime with dark anniversaries. ‘Tracy’s death was a really sad business.’

And if Tracy were alive today, what would he make of Nick Cave: The Exhibition? Ah, Nick suspects, he would probably give him shit for being a wanker. Pennants, you prick! Nick laughs at the thought, questions, ‘How you can love someone so much – and yet have so many punch-ups with that same person? We used to hit each other all the time. I don’t even remember why now.’

Despite the gibes he’s been getting, Nick says, ‘I’m actually very proud of the exhibition at The Arts Centre. Trying to look at it from the outside, as a show about this guy called “Nick Cave”, I think it is kinda interesting.’ But the 2007 ARIA Hall of Fame induction is harder for him to come to terms with. He looks over at Bleddyn and realises his friend is rattling on about TS Eliot and the artistry of theft, a much worked-over topic between them whether they’re talking about blues music or Greek mythology or, as Nick likes to put it, ‘my favourite subject, me’.

Bleddyn shifts his conversation to Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road and asks, ‘What did you think of that vision of the fish at the end?’ Then it’s back to TS Eliot and how the world will end ‘not with a bang but a whimper’.16

Nick feels a vague headache coming on, one of the byproducts of the insomnia he suffers when he has had a bad night. ‘Yes, Bleddyn,’ he says. ‘Cheer me up already, and no more end-of-the-world stuff, please.’ But Nick is only half-listening as he starts to jot down ideas for the acceptance speech tonight. ‘Look, do you know any good dirty jokes I can use? I think I’d like to be funny.’ He hunches over his notebook and scratches away. Bleddyn says something crude in French as their car hauls to a stop again, caught in traffic barely half a block further down the road. Nick begins to sing The Loved Ones’ ‘Sad Dark Eyes’ under his breath, till it trails off into an embarrassed croak while the car shunts along.

The song is all mixed up inside him, the words of Gerry Humphrys merging with his own lyrical improvisations. It’s yet another bastard marriage in a classic interpretative repertoire that includes Cave’s diabolically violent ‘Stagger Lee’, a drastic rewrite of an old blues ballad formerly known as ‘Stack O’ Lee’, and a raucously possessed slant on Bob Dylan’s ‘Wanted Man’. Over the years, the way Nick Cave reworks songs and makes them his own will almost be as important to understanding him as his originals. Maybe the covers are even more revealing, as Bleddyn implies when speaking of TS Eliot’s ideas about theft and transcendence. How does one define a voice you can call your own anyway? It comes from everything you’ve borrowed.

‘Sad Dark Eyes’ still sounds good to Nick. It makes him think again of being a kid in Wangaratta, of his eldest brother, Tim, coming back to their home town from yet another moratorium march in Melbourne against Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Tim was the real wildcat in the family. A young Nick relished hearing his teenage brother’s tales of the big smoke, as well as the black wafers of vinyl Tim returned with: LPs by Cream, Jimi Hendrix and, yeah, The Loved Ones.

Wangaratta slides over Nick’s vision of St Kilda today and overwhelms it. Wang! The heat haze of summer rippling off the bitumen, the subzero winter mists chilling a wire fence so cold you couldn’t touch it in the morning. It’s like the country town is floating, and him as a boy along with it. ‘That town was all about walking,’ Nick says, with undisguised affection, ‘just wandering around on foot.’ More random thoughts roll by: a teacher holding up a Bic biro and explaining to the class they won’t need their fountain pens anymore; his school stopping to witness grainy black-and-white satellite footage of the first man on the moon. The closest Nick ever got to sex education, he says, was a documentary in biology class on the birth of a kangaroo. Left to his own devices, Nick liked to contemplate ‘how hot Elizabeth Montgomery looked on Bewitched, the way she wrinkled her nose’ to cast a spell. Oh boy. ‘I couldn’t work out whether it was her or Carolyn Jones as Morticia on The Addams Family that first aroused my interest in women.’ Talk about patterning behaviour. The secretarial types and the Goth girls imprinted on his formative desires – thank you, crap sixties television. Nick looks startled and says, ‘Oh my god, I married Morticia!’ Then he relaxes again and says, ‘Please stop me. I am really talking rubbish now.’

These days, whenever journalists ask him about his past he tells them to ‘Just Google it!’17 They usually do. But it’s mostly half-truths and data, not much inner life or mystery; it all seems inadequate or wrong. It took Nick a long time to get over his disgust with himself about doing interviews during the 1980s, and the awful truth that they were among the few times he allowed intimacy into his increasingly drug-fucked life. No wonder he was so ambivalent about the process. Then to have things he said ten, twenty, even thirty years ago quoted back at him like he would never change his mind, let alone remember it? If he even meant what he said in the first place? His mother tells him that it’s his own fault. ‘You do like to exaggerate when you tell these people your stories, Nick.’18

Dawn was right. Nick would develop a practice of rehearsing his quotes in casual conversations till he had them sounding exactly how he wanted them to be in print. Once he had them down, he’d mostly stick to the script – and would often regret it when he didn’t. Like all contrary artists, Nick Cave wants his tale told on multiple levels: larger than life, yet right on point; how it was, but always through the prism of how he sees it now.

In his Birthday Party days Nick regarded his audience with something approaching disgust; these days he appreciates the communal energy that rallies around him. Now and again the old confrontational edge will rear up, of course, giving people a frisson of how it feels to be attacked as much as entertained. But the beast in Nick is well reined in. It’s getting easier and easier to forget he was never an Oz rock hero at the start; you will discover that quickly enough on Google. If anything, Nick Cave cast himself as the villain to succeed: the prince of darkness, the junkie Hamlet of rock ’n’ roll19 … yak, yak, yak … God, how the press can go on. And having become a drug-free family man, driver’s licence and all, ‘I am suddenly “Quiet and Contented of Hove”!’ Living one’s life under other people’s slogans can be a laborious business, especially when some of them have sprung, well practised, from your own lips.

After a while the stories run on without him and seem to be about someone else. Decades of this have made him obsess about controlling his own narrative. He admits he finds it impossible to say much in public without seeing the words appearing in black and white before his eyes. ‘It can make you a little self-aware.’

In any case, here he is in late 2007, not doing so badly: on his way to Australia’s rock ’n’ roll hall of fame. An international star with million-selling recordings, including ‘Where the Wild Roses Grow’ (his duet with fellow Australian Kylie Minogue) and classics such as ‘The Ship Song’, ‘Red Right Hand’, ‘Into My Arms’ and ‘The Mercy Seat’. The résumé is so rich as to be boundless: writing a row of film scores and award-winning scripts such as The Proposition (2005); soundtracks for theatre and dance projects from London to Reykjavík; invitations to curate arts festivals and give lectures; the odd bit of acting over the years (‘I think I’ve proved it’s not my forte; I’m stiff as a board’); and even a set of violent, white-trash, one-page plays he worked on with Lydia Lunch when he was off his head in his twenties. It has been a long journey from those chaotic early days to singing with the likes of Johnny Cash20 and creating songs that people ask to be married and buried to. And yet in so many ways it is all of a piece.

‘There’s more to come, more to come,’ Nick says, hinting at a veritable deluge: another film script in development about a sex-addicted door-to-door salesman21; more soundtracks; and a collection of poems tracing the history of violence in literature that he plans to edit if the copyright issues can be ironed out. As if that’s not enough, the singer launched a side-band project in 2006 called Grinderman. Their sexed-up, prog-rock, blues-metal and what Nick thought were some pretty satirical lyrics are earning him a fresh round of misogyny charges from critics, as well as plenty of midlife-crisis comments. Even from his mother. Dawn told Susie, ‘I think Grinderman is Nick’s change-of-life record.’ Nick rolls his eyes. The porn-star moustache he has taken to sporting only encourages such impressions. Even so, Nick wonders how anybody could regard a Grinderman song such as ‘No Pussy Blues’ as anything other than self-mocking. A friend messaged him earlier in the day from Los Angeles about the last Grinderman show there, saying he had never seen so many girls in miniskirts in one place before. It really makes Nick laugh. He texted back: ‘It’s sexy music, man! The girls love it! I tell you, Grinderman are the rock ’n’ roll equivalent of chick lit!’22

As usual Nick feels the old reactive surges sparking extremes in him, the desire to take things even further now that people are angry or upset. ‘If people think what I say in Grinderman is bad, wait till they see what I am doing next.’ In this Nick has long felt an unlikely bond with a renowned feminist thinker and fellow Australian expatriate. ‘I love Germaine Greer, if only for the fact she just stirs things up again. I don’t always agree with everything she says but I understand, to a degree, where she’s coming from: that it’s not always necessary to be right. Sometimes just to provoke is enough.’23

While the self-titled Grinderman release continues to dominate Nick Cave’s life over 2007, a fresh album of songs entitled Dig!!! Lazarus Dig!!! is ready to go with his main band, The Bad Seeds. Like the gridlocked traffic Cave is caught in today, this new Bad Seeds album has been postponed by his record label, Mute, until people digest the Grinderman recording and the plethora of interests the singer is unleashing on the world. Mute label boss Daniel Miller is worried about how to manage it all: the range and quantity of Nick’s output verges on a mania.

What’s driving this creativity? An ex-junkie’s need to stay busy, perhaps? This theory has been doing the rounds for ages. It’s a post-rehab ‘condition’ that may have added velocity to Cave’s output since the late 1990s, but a close look at the singer’s life shows the raging work ethic was always there. For a time in the 1980s you could argue Nick Cave was the hardest-working heroin addict in showbiz. At his personal worst, during the West Berlin years, his output was just as phenomenal, even frenzied.

People say Nick is a driven man: all those records, books, films and live shows across the planet; all the people who have fallen in his wake. Cave seems to share in Keith Richards’ hardy rock ’n’ roll voodoo in that respect, standing where others have dropped like flies. Again and again friends will note how ridiculously lucky Nick is. The guy always lands on his feet. Nine lives like a cat. Others say you make your own luck. But there was something Shane Middleton, the roadie for Cave’s teenage group, The Boys Next Door, observed a long time ago that struck a deeper nerve: ‘I don’t think Nick’s a driven man, but a fleeing man, running from the fear of failure.’24

It’s true there’s a need to prove his talents are still there, to show that he hasn’t stopped moving forward. Maybe he is striving to prove something to his long-dead father, too? The pop psychologists would love to hear him admit to such thoughts. ‘We Call Upon the Author to Explain’, a song on Dig!!! Lazarus, Dig!!!, goes right to the heart of that material: rock stardom, fan worship, dead-father hang-ups, disputes with God, the full technicolour yawn.25

‘It’s all good.’ That’s the shorthand Nick’s older sons, Jethro and Luke, use on him whenever he bugs them about how they are going. The boys were born to two different mothers in two different countries – Beau Lazenby in Australia and Viviane Carneiro in Brazil – ten days apart in 1991.26 It’s one way to start a decade. Distance would strain and complicate the relationship with Jethro as Nick reached out and tried to be a father when he became older. He would be much more involved with Luke’s day-to-day upbringing in London, and was in some ways saved from addiction by having to look after Luke. Nick valued being a father more than anything else in the world, though he may not have appeared to be the most orthodox of parents. He started making changes; he was fighting to get a few things right. But it wasn’t all good before he met Susie in 1998. Not at all. PJ Harvey ditching him over the phone because of his heroin habit had caused him to break down and cry.27 ‘Just say you don’t love me,’ he’d demanded as she gave him the bad news. ‘Just say that you don’t love me.’ She did. And that was really that. He’d half-joke that he almost dropped his syringe when she told him it was over, but that kind of honesty was as much some bravado to mask the hurt. It was a devastating wake-up call for Nick. That and Susie Bick refusing to see him till he got clean.