9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

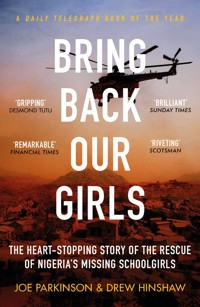

A 2021 Daily Telegraph Book of the Year 'Had me gripped from the outset' Fergal Keane 'Everyone should read the testimonies of the Chibok girls who survived the capture' Malala In the spring of 2014, an American hip hop producer unwittingly triggered an online hurricane with a quickly thumbed tweet featuring a four-word demand: #BringBackOurGirls. The hashtag called for the release of 276 Nigerian schoolgirls who'd been kidnapped by a little-known Islamic terrorist sect called Boko Haram. Within hours, the campaign had been joined by millions, including some of the world's most recognizable people: Oprah Winfrey, Pope Francis, David Cameron, Kim Kardashian and Michelle Obama. Their tweets launched an army of would-be liberators – American soldiers and drones, Swiss diplomats, spies and glory hunters – into an obscure conflict in a remote part of Nigeria that had barely begun to use the internet. But when hostage talks and military intervention failed, the schoolgirls were forced to take survival into their own hands. As the days in captivity dragged into years, they became witnesses, and often victims, of unspeakable brutality that they chronicled in secret diaries. Many of the girls were Christians who refused to take the one easier path offered to them – converting their captors' extremist creed. Bring Back Our Girls is an urgent and engrossing work of investigative journalism that unfolds across four continents, from the remote forests of northern Nigeria to the White House; from Khartoum safe houses to gilded hotel lobbies in the Swiss Alps. It plumbs the promise and peril of an era whose politics are fuelled by the power of hashtag advocacy – and at its centre stand some exceptionally courageous and resourceful young women.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 660

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

First published in the United States of America by HarperCollins Publishers 2021

First published in Great Britain by Swift Press 2021

Copyright © Joe Parkinson and Drew Hinshaw 2021

The right of Joe Parkinson and Drew Hinshaw to be identified as Authors of this work have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN (hardback): 978-1-80075-027-2

ISBN (paperback): 978-1-80075-029-6

eISBN: 978-1-80075-028-9

It is a must for trials to come But if we stand firm to the end We will receive the crown And be like the angels

—Mama Agnes

Inflexibility Partiality Arrogance Haste Impotence Ignorance False Promises

—The Seven Deadly Sins of Mediation

CONTENTS

Authors’ Note

List of Characters

Map of Northeast Nigeria

Prologue

PART I: Kidnapped

1 “Gather Outside”

2 The Day of the Test

3 The Perfume Seller

4 Kolo and Naomi

5 The Caretaker of an Orphan

6 @Oby

7 “Timbuktu”

8 #BringBackOurGirls

PART II: An Open-Air Prison

9 The Blogger and the Barrister

10 Thumb-Drive Deal

11 Malam Ahmed’s Rules

12 The Mothers’ March

13 “You Must Write One Too”

14 Tree of Life

15 The Senator’s House

16 Maryam and Sadiya

17 “These Girls Are Global Citizens”

18 Christmas

PART III: A Global Conflict

19 The Foreign Fighters

20 Agents of Peace

21 The General

22 Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego

23 Sisters

24 The Imam

25 The Escapade

26 The Deadline

27 The Windows Are Closed

PART IV: A Breakthrough

28 “I’m Not Going Anywhere”

29 The Fire

30 “Never Trust a Breakthrough”

31 Meeting in Manhattan

32 Praise God

33 The One You’ve Been Looking For

34 “Now There Is Trust”

35 Naomi and Kolo

Epilogue

Postscript

Acknowledgements

Glossary

Image Section

Notes

Selected Bibliography

AUTHORS’ NOTE

The following is a work of reporting, conducted over six years and on four continents with hundreds of individuals involved in the search for the Chibok schoolgirls, including twenty of the young women themselves. It is also informed by a firsthand document, a diary, recorded at considerable personal risk during captivity and smuggled into freedom, which has been lightly edited for clarity.

LIST OF CHARACTERS

SENIORS AT CHIBOK GOVERNMENT SECONDARY SCHOOL FOR GIRLS

Naomi Adamu

Maryam Ali

Sadiya Ali

Saratu Ayuba

Hauwa Ishaya

Lydia John

Rebecca Mallum

Palmata Musa

Ladi Simon

Hannatu Stephen

PARENTS OF CHIBOK STUDENTS

Kolo Adamu—Naomi’s mother

Rifkatu Ayuba—Saratu Ayuba’s mother

Mary Ishaya—Hauwa’s mother

THE MEDIATORS

Tijani Ferobe—a Quranic scholar and friend of Zannah’s

Pascal Holliger—a Swiss diplomat from the Human Security Division

Fulan Nasrullah—a fundamentalist–turned–terrorism analyst

Ahmad Salkida—a freelance journalist and prolific tweeter

Tahir Umar—an elderly former disciple of Boko Haram leaders

Zannah Mustapha, “the Barrister”—a lawyer and orphanage director

NIGERIAN GOVERNMENT

Muhammadu Buhari—former general and president of Nigeria from 2015

Oby Ezekwesili—former education minister, #BringBackOurGirls protest leader

Goodluck Jonathan—president of Nigeria, 2010–2015

BOKO HARAM

Malam Abba, “Qaid”—a commander, and the Chibok girls’ abductor

Malam Ahmed, “the Malam”—the Chibok girls’ Islamic teacher and guardian

Ali Doctor—a Boko Haram physician

Aliyu, “Emirul Jesh”—Shekau’s chief military commander and executioner

Abubakar Shekau, “the Imam”—leader of Boko Haram

Abu Walad, “Rijal”—a foot soldier and guard of the Chibok girls

Mohammad Yusuf—“The Martyr,” slain founder of Boko Haram

Tasiu, aka Abu Zinnira—Boko Haram’s spokesman

US GOVERNMENT

John Kerry—secretary of state

Barack Obama—POTUS

Michelle Obama—FLOTUS

John Podesta—senior counsellor to President Obama

BACKGROUND FIGURES

Mama Agnes—a northern Nigerian gospel singer

Jack Dorsey, “@Jack”—founder and CEO of Twitter Inc.

Amina Rawaram, “The last Diva of the Sahara”—a Maiduguribased singer popular in the 1960s

PROLOGUE

Michelle Obama was upstairs in the White House residential quarters, watching the morning news report a story of suffering and social media and wondering whether to tweet. It was May 7, 2014, an overcast Wednesday in Washington, and all the major breakfast shows were leading with the same harrowing tale.

Thousands of miles away, in a remote Nigerian town called Chibok, 276 schoolgirls had been kidnapped from their dormitory on the night before their final exams. They’d been dozing on bunk beds, studying notes, or reading the Bible by torch. They were high-school seniors, a few hours of test questions from graduating as some of the only educated young women in an impoverished region where most girls never learned to read.

Then a group of militants barged in, bundled them onto trucks, and sped into the forest. The students had become captives of a little-known terrorist group called Boko Haram, which filled its ranks by abducting children. The girls’ parents chased after them on motorbikes and on foot until the trail went cold. For weeks, few people seemed to notice. The schoolgirls looked set to be forgotten, new entries on a long list of stolen youth.

But this time, something mysterious aligned inside the algorithms that power the attention economy. A small band of Nigerian activists on Twitter coined a hashtag calling for the hostages’ immediate release. Through the unpredictable pinball mechanics of social media, it shot out from West Africa and into the celebrity-sphere boosted by Hollywood and hip-hop royalty, then captured the global imagination. People all over the world began tweeting the same clarion call: #BringBackOurGirls.

The network news channels found the story irresistible. Anchors choked up retelling a tragic sequence of events that seemed to connect the world’s richest and poorest people through the universal pain of parental loss. A class of teenagers had been studying toward a better life, chasing aspirations that made them not so different from ordinary Americans, whose own high schools knew the ever-present danger of adolescent gun violence.

Now these girls were trapped in a ghastly, faintly understood conflict far away, hostage to unambiguous evil. More than that, they needed your help. Here was a chance to take part in the crowdsourced liberation of more than two hundred innocent victims terrorized for their determination to learn.

Watching the news reports upstairs, the first lady felt the same wrench of empathy that millions of others would express online: Those could be my daughters. Michelle dialled her chief of staff. Tina Tchen, a Twitter sceptic, wasn’t expecting the call. A lawyer by training, careful and attuned to unforeseen risks, she didn’t have an account and wasn’t sure that Twitter.com was a presidential-enough platform for the first lady. Once a tweet went live, you couldn’t control what happened.

Michelle, too, harboured reservations about social media and how much she should put herself out there. She had never made a major statement on foreign affairs, let alone waded into a war. What if her tweeting about Boko Haram made the situation worse?

But this story moved her. It was a moral issue, she would tell a friend, bigger than foreign policy. On her office bookshelf, next to a picture of her daughters, sat I Am Malala, the memoir of the Pakistani activist for girls’ education who had recently visited the White House.

“I think I want to do this,” she told Tina. “I want to do this.”

Her media team scrambled to choreograph the tweet. Staff hurried office supplies into the White House Diplomatic Room, trial-and-error testing Twitter photos in the same circular reception hall where Franklin Roosevelt once recorded his Fireside Chats. Michelle’s aides fumbled with different-size placards, attempting to find a board of optimal dimensions, and tested out sharpies to see how thick the marker should be for legibility on a small screen. They debated whether the press secretary should snap the picture on her phone. Or maybe an official White House photographer should set up his professional camera.

Michelle descended the staircase in a red, white, and blue floral dress, rushing to a personal appointment. The motorcade was waiting, but she could do this fast. Standing opposite a portrait of George Washington, she stared intently into the photographer’s lens, gripping a pearly white placard: “#BringBackOurGirls.”

She dashed into her car, while an aide typed up her caption and clicked Tweet: “Our prayers are with the missing Nigerian girls and their families. It’s time to #BringBackOurGirls.—mo”

That modest gesture was liked or retweeted by some 179,000 people and seen by hundreds of millions across the world, becoming the most shared post of a frenzied campaign that tested the power of social media to reshape events thousands of miles away. In the space of a few weeks, two million Twitter users, with a tap of the screen, repeated the same demand. This was a shared purpose, proclaimed by ordinary people from every corner of the map and some of the world’s most famous names: Hollywood celebrities, prime ministers, rap stars, the pope, Ellen, Angelina Jolie, Oprah, Harrison Ford, David Cameron, Mary J. Blige, the Rock . . .

And quite possibly you.

A DAY SHORT OF THREE YEARS LATER, THE SKIES ABOVE NORTHEASTERN Nigeria were empty except for one solitary aircraft. A soft rain streaked the windows of a Russian helicopter juddering through grey clouds. Inside the cabin, a Nigerian lawyer lifted a list and a pen from the chest pocket of his crisply ironed ash-coloured kaftan and studied the names through thick-framed Calvin Klein spectacles. Across from him sat a diplomat from Switzerland, nervously ticking through the final preparations for Phase Two. If everything went according to plan, their team could still make the rendezvous point by 4:00 p.m.

The helicopter headed southeast, rumbling over thorn forests and villages torched and abandoned during almost a decade of war. On the roads below, lookouts would be monitoring them, the passengers assumed, tracking their movements. One misstep could shatter the process, years in the making. The operation, hashed out over endless encrypted messages and meetings in safehouses, hung on a pair of delicate concessions. The first involved five militants released from jail now being driven to the front lines. Second was a black bag stuffed full of euros in high-denomination notes, the currency Boko Haram had demanded. Its contents were strictly secret.

Only a few senior officials in either of their governments knew the agreement the two men and their small team of mediators had painstakingly engineered. Along the way, they had lost friends and contacts to assassinations and imprisonment and had mourned when previous deals collapsed. Each assumed their phones were tapped, their routines followed. Both had sworn to observe a total information blackout at each stage of an operation that could be undone by a single errant tweet or a picture posted on Facebook. Not even the lawyer’s family knew where he was.

They were the last in an army of would-be liberators, spies, and glory hunters that had descended on Nigeria to find a group of schoolgirl hostages that social media had transformed into a central prize in the global War on Terror. A few days of tweets had lit a fuse of unintended consequences that had burned for years, the forces of Silicon Valley disrupting a faraway conflict on Lake Chad. Satellites had spun in space, scanning the forests of a region whose population had barely begun to use the Internet. The air power and personnel of seven foreign militaries had converged around Chibok, buying information and filling the skies with the menacing hum of drones. Yet none of them had rescued a single girl. And somehow the fame that once started a race to free the young women had also prolonged their captivity.

The helicopter bumped to earth next to a military outpost ringed by half-buried tires and sand-filled oil drums with a chain of white Toyota Land Cruisers parked on the cracked tarmac. The two men stooped as they stepped off the helicopter and went their separate ways.

The lawyer entered the first car of a convoy that rattled north over a dusty road, passing deserted farmland and the charred mudbrick walls of villages whose few remaining residents were too old to leave. Outside the window lay fallow fields, overlain with discarded tools and an upside-down rust-coated wheelbarrow.

The area was notorious for land mines and roadside bombs. Each driver steered carefully into the tread marks left by the car in front, their bumpers mounted with fluttering Red Cross flags. The lawyer told himself there was nothing to fear: “The prayers of the orphans will protect you.”

His car halted, and its flashing brake lights signalled the convoy behind to stop. Fighters in fatigues, their heads wrapped in turbans, were gathered on the other side of the dirt road, standing alert beside waist-high grass. In the branches of acacia trees, and crouching behind bushes, the lawyer could see other figures, training their rifles. He held his list, the silence broken by the warning chime of a Toyota door left ajar.

In the distance he could see a snaking line of silhouettes, dozens of women wrapped in dark, floor-length hooded shrouds billowing in the breeze. They were stepping through long grasses flanked by armed men. The figures looked exhausted, each trudging awkwardly toward him. Two of them were walking on crutches, and one was missing her left leg below the knee. Another had her arm draped in a sling. One carried a baby boy on her back.

These were the students that millions had tweeted about, then forgotten, but none of them had any idea about the social media campaign, and they lacked the faintest notion that anybody except their parents had been advocating for their release. These schoolgirls, almost all Christians, had come of age in captivity. To keep their friendships and faith, they had whispered prayers together at night, or into cups of water, and memorized Bible passages in secret. At risk of beatings and torture, they had softly sung gospel songs, fortifying each other with a hymn from Chibok: “We, the children of Israel, will not bow.”

The women, eighty-two in all, walked onto the road and halted opposite the lawyer, huddling into two lines, staring ahead with their eyes fixed. Some linked arms, others squeezed hands, their baggy clothes concealing the few possessions they’d managed to accumulate, strips of coloured fabric and small twigs for pinning their hair.

One of the women was trailing behind, dressed in a grey shroud and walking with a slight hunch. Tied around her thigh, hidden from view, was something the men with guns had never found, an article of defiance. It was a secret diary, filling three notebooks, a firsthand record of the women’s ordeal.

Her name was Naomi Adamu. It was her 1,118th morning in captivity.

PART I

KIDNAPPED

1

“GATHER OUTSIDE”

CHIBOK APRIL 14, 2014

The class of 2014 at the Chibok Government Secondary School for Girls were only four weeks from finishing senior year when almost three hundred of them were seized by armed men and packed onto pickup trucks that disappeared into the night. It was a Monday, and the students had spent the afternoon finishing a three-hour civics exam and the evening relaxing on campus, studying in their dorms, or gathering in small circles in the prayer room. Some had been singing cathartic sabon rai, or “reborn soul” hymns or practising a local dance called “Let’s Shake Our Waist.” The following day they were to sit for a maths final, which their teacher, Mr. Bulama, had warned would be so hard it would make them cry.

The Chibok seniors, each wearing blue-and-white-chequered uniforms sewn with the motto “Education for the Service of Man,” were only a few tests away from becoming some of the first in their families to graduate. Nigeria, over their parents’ lifetime, had become one of the most literate societies in the developing world, but in their corner of it, just 4 percent of girls finished high school. To complete a basic education, the students each had needed to master two second languages, Hausa and English, in addition to their mother tongues, all on top of their chores at home: cleaning, babysitting, or cooking over firewood stoves. For the better part of a decade they had shared and fought over bunk beds in the overcrowded dormitories of a school with no electricity, trying to pass exams that were challenging for even the most high-achieving students in West Africa. But the real struggle of their lives was just about to begin.

At twenty-four, Naomi Adamu was one of the oldest, a student who had prayed and fasted more times than she could count to get through high school. Petite, with a teardrop-shaped face and slender arched eyebrows she liked to outline with an angled brush, she was known to her younger classmates as Maman Mu, Our Mother. Yet when the incident began, she would find no guidance to offer them, and it would be more than a year before she discovered herself able to be the leader she wished to be.

The air that night was stiff and muggy, cut by a breeze that rippled over the flat brushland outside the school gate and through the window, next to the thin foam mattress Naomi shared with her cousin Saratu Ayuba. Well over one hundred students were lying on rows of rusting spring iron bunk beds in the Gana Hostel, one of the school’s four single-story dorms. Above them, a dust-coated ceiling fan hovered idle. The teachers had all gone home for the night, and it was pitch dark, and quiet, until Naomi’s eyes opened shortly before midnight to the sound of distant popping.

Half asleep, her dorm mates turned to each other, confused as the crackling noise faded then returned. It was sporadic but growing louder and presumably closer, echoing off the cement walls. From adjacent bunks Naomi could hear the rustling of bedsheets, then anxious whispers. Her classmates were talking about Boko Haram. On campus, there wasn’t a single girl who hadn’t heard of what this group of fundamentalist militants had done at boys’ schools in distant towns. But the teenagers had been told by their teachers that a girls’ campus would be safe, protected by the military.

“Should we run?”

“No. They told us to stay.”

For a moment the girls debated.

Then came a thunderous roar, followed by the crash of deafening explosions, sending the hostel into pandemonium. Naomi threw herself flat on the cement floor, her cheeks next to flip-flops, open textbook pages, and scattered study notes. In one corner, a small group of students began running through a prayer, their heads bowed as classmates scampered between bunks or hid beneath beds. Some yanked the wire frames toward the wall to barricade themselves in. In the distance, the light trails of rockets cut across the night. Chibok was under attack.

“We should run!”

“No! We should not run! We should pray!”

The school’s security guard, a frail man in his seventies whom the girls called Ba, or Dad, hobbled into the dorm and asked for help.

“What should we do?”

The militants might spare the young women, but any man found would be slaughtered, he explained. “They won’t have mercy on me, let me go and hide,” he said, and disappeared into the night.

Girls began bracing themselves to run, stuffing clothes into bags, torches weaving skittishly in trembling hands. Students with phones were furiously dialling family or friends. But the cell service was weak, and for those who could connect, the clatter of gunshots and bursting grenades made it almost impossible to hear. Mary Dauda stared into a phone that had dropped a call to her brother, sobbing at her failure to reach him and mumbling, “God have mercy.” Margret Yama managed to briefly speak to her brother, Samuel. But she was so frightened she could barely talk, and as he begged her to flee, the line dropped. Naomi’s phone was ten years old, a battered but trusty grey Nokia 3200 handset held together with a rubber band, and she frantically dialled her contacts until she managed to reach Yakuba Dawa, a neighbour. “Stay where you are,” he shouted immediately, before the call cut out.

Separated from Saratu in the commotion, Naomi had only her ears to guide her. From beyond the school gates, she could hear the sound of motorbike engines approaching, then coming to a halt. Outside, two men’s voices were chatting over the clanging sound of metal on metal, trailed by the jangle of a chain. The rusted hinges squealed as the gate eased open.

“There is nobody here,” a male voice said.

“No,” said the other. “There are girls here.”

The school campus was an island unto itself, a yellow-painted congregation of one-story buildings, perched on the vacant scrubland on the far outskirts of town. Its low cement walls were the last structure on a road that meandered into a flat horizon, and there was nobody around to help as a convoy of Toyota Hilux trucks and motorcycles halted at the school’s green iron gate. An army of men began exploring the campus, their boots and sandals sinking into the sand of a courtyard lit by a full moon. One of the last was their leader, a stocky man with jutted front teeth wearing a red cap, who strode toward the dormitory and hollered to the teenagers inside. He hadn’t expected them to be there.

“Gather outside,” he shouted.

“Don’t worry!” said another man through the window. “We are soldiers.”

The students began to slowly move across their rooms, swimming through darkness toward the voices in the doorway. There was no alternative but to take these men at their word. Rhoda Emmanuel, a pastor’s daughter, grabbed a blue Bible and tucked it inside her clothes. Maryamu Bulama carried her own copy of the Bible. Naomi furiously stuffed a bag with as many essentials as she could think to collect: a red shawl, her school uniform, her blue Bible, 3,600 naira (about $23) in pocket cash, and her Nokia. “I’m very sure it’s Boko Haram,” she said as she followed the crowd filing into the courtyard. Naomi found her cousin Saratu in the scrum and in a whisper revealed the fear running through her mind. “I’m not baptized yet.”

2

THE DAY OF THE TEST

Until the third week of April 2014, hardly anyone had ever heard of Chibok, a grain-and-vegetable-farming community of pink tin-roofed homes and whitewashed churches that stands alone under the hard desertlike skies of Nigeria’s northeast. Built at the foot of a solitary hill studded with jagged grey boulders, its patchwork of single-story cement buildings blends into a parched landscape of dusky yellow and brown grasses. It is home to around seventy thousand people, with the feel of a small town. The nearest village lies a half day’s walk over the sole dirt road available to cars, or along footpaths that skirt sand-clogged streambeds where creeks used to flow. Those trails thread through peanut, bean, or maize plots that fade away into the distance. After that, there is only tough soil for miles, punctured by a lonely set of four telecom masts providing patchy phone service for one of the dwindling com munities on Earth still not reliably connected to the Internet.

At dawn, Chibok’s families step out together, or pedal singlespeed bicycles, to reach small farms and tend their crops before the sun provokes daily highs that often top 100 degrees. Neighbours sell each other the crops they don’t eat themselves in the stalls of the town’s open-air market, where mechanics clang metal tools against the broken parts of motor scooters. The rhythm of commerce is slow. The grocery-stall shopkeeper, among the few residents wealthy enough to own a refrigerator, is nicknamed Dangote, after Nigeria’s richest billionaire. For entertainment, teenage girls dreaming of adventures beyond town often meet at a portrait studio where they pose in front of aspirational backdrops of gilded mansions, manicured gardens, or the skyline of Dubai.

For Chibok’s residents, April is traditionally a month of celebration. It is the time of year when the air is no longer spiked with the coarse, eye-aggravating sand brought by the harmattan, a harsh wind that blows south from the Sahara during the long dry season. It is also the month, along with December, when the town holds weddings. Local custom holds that each groom must give his bride a bicycle, for her personal mobility, and later, grant each of his daughters a parcel of land, for financial independence. May brings damina, the rainy season, when the streets, unnamed and unpaved, transform from dust to clay-like sludge. An apocryphal story holds that the word Chibok comes from the sound of a sandal slapping in mud: chi-bok.

The town is so detached from its neighbours that it speaks its own language, Kibaku. Just one-tenth of 1 percent of the country understands it. An hour’s drive beyond the boundaries of what is called the Chibok Local Government Area, it is rare to find anyone who can muster even the basic greetings of a community that might have remained in its pleasant obscurity were it not for an agonizing series of unexpected events that began one night while its parents were sleeping.

Mimigai? “How are you?” Yikalang. “All is well.”

SECLUDED AND RARELY VISITED EVEN BY ITS ELECTED OFFICIALS, THIS small town might not have mattered to the world if its story didn’t trace the fate of a country whose success or failure will shape the next century. Nigeria is Africa’s most populous nation, home to 206 million people, half of them not yet adults, a citizenry that will double and outnumber Americans by 2050. Some five hundred languages are spoken on its soil.

And yet a picture is often drawn that Nigeria is two separate countries tucked inside the same borders, each complicating the fortunes of its opposite half. The south, verdant and tropical, is largely Christian and relatively more educated, with prosperity trickling into port cities along an oil rig–studded shore. The British Empire, which conquered Nigeria in the nineteenth century, considered the southerners more rebellious and pushed them to adopt Christianity, the English language, and the colonial school system.

The north, hotter, drier, and sitting on the southern fringe of the Sahara, was different. There, the imperial government coerced Muslim emirs and sultans into carrying out what Nigerian scholars would later call subcolonialism: a colonialism of the colonized. So long as northern elites obeyed the British, they were empowered to spread their religion—Islam—and their language, Hausa. By the time the empire fell, in 1960, the flag of an independent Nigeria would rise above a country that had been converted en masse to the world’s two largest faiths, a vast experiment to test whether any nation so conceived could long endure.

Chibok, however, became a Christian town in the Muslim north, one of the small communities complicating that broad and simplistic divide. It had been founded in the 1700s by refugees fleeing bands of Muslim slave raiders. The settlers built houses beneath a single rocky hill, a safe distance removed from the slow and violent decline of the Borno Empire, a trans-Saharan kingdom fading into sand. As locals would boast, not even the nineteenth-century revolutionary Usman dan Fodio had subjugated Chibok when his army converted much of Nigeria’s north to Islam. The slave traders, filling ships headed to the New World, never made it as far upland as their town. Local children learned that their community had been the last in the country to submit to the British Empire.

For centuries, the residents had kept their ancestral religions, praying for full harvests and sacrificing livestock on sanctified rocks. But by the time Nigeria declared independence, Chibok had made itself an exception to the country’s religious geography. It was a devoutly Christian town in a region of Muslim villages and cities. The catalyst was a group of American missionaries who came to build a school.

IT IS SAID THAT A VISITOR CAN TELL WHAT A COMMUNITY VALUES MOST BY its most prominent building, and in Chibok, that structure was a sprawling boarding school visible from miles away, its pink tin roofs bleached by the blazing sun. Boxed in by a low wall with a single metal gate, the Chibok Government Secondary School was the first to educate girls in all of the surrounding Borno State, a point of local pride. Hundreds of young women came from miles around to study at CGSS, wearing the blue-and-white uniform, each sewn with an emblem containing the school motto and three symbols the town chose to define itself: a book, a pencil, and a chilli pepper, a fruit hardy enough to survive Chibok’s nine months of dry, sandswept weather.

CGSS had once been an arid, weedy grass patch until a family of missionaries arrived in a Ford pickup on an April evening in 1941. The Petres of Hagerstown, Maryland, brought a cook, a gardener, and a local man they called a wash boy, along with a gas lantern they carried door-to-door to introduce themselves and an entirely new worldview. Over years, Ira Petre made two efforts that endeared him to the town: he learned its history, and he raised his children to speak fluent Kibaku. The town’s parents eventually allowed him to teach the alphabet and the Bible to a small group of about thirty farm boys who studied each morning on a row of mudbrick benches. That temporary outdoor classroom, washed away each rainy season, would gradually evolve into a boarding school for girls.

The faith continued to spread through song after a local early convert and chorister, Mai Sule, organized Chibok’s children into a choir that met each night under the stars. They sang hymns translated into Kibaku and set to a pattering beat, while recently converted parents listened with pride. After the Petres returned to Maryland, a Christian community grew and flourished. Residents built cavernous whitewashed churches decorated with brightly coloured banners proclaiming evangelical messages. They held competitive Bible quizzes. Muslim and Christian neighbours would get together to trade holy books, and at an Islamic wedding it was not uncommon to hear Christian hymns.

All in all, the town, though small and barely connected to the rest of the country, was an expression of one vision for modern Nigeria—coexistence of Christians and Muslims progressing together in small steps while battling the odds to raise and educate their children. On April 13, the last day of Chibok’s peaceful seclusion, the community held an interfaith wedding, the reception under a pavilion pitched over a dusty courtyard, the tables decorated with polyester flowers. The owner of a local welding shop, a Muslim, married a Christian woman whose parents were prominent members of the local church. Flower girls in matching glossy dresses sat on plastic chairs while the tall and handsome groom, Wamdo Dauwa, gave his bride her customary bicycle. But there was another vision for Nigeria lurking in the towns and villages beyond Chibok, and on the next day, it began driving toward the school.

CHIBOK, APRIL 14, 2014, NOON

Naomi Adamu pencilled her name into the long blank box on the cover page of her final exam, draping the decorative apostrophe she liked to add between the a and the o: Na’omi. It was just about noon on a Monday in the final stretch of senior year for the young woman, who mouthed a prayer as she opened the thin, rustling pages.

“Instructions to Candidates,” began the test, a three-hour exam that would assess students’ knowledge of Nigeria’s government. “Answer all the questions. Each question is followed by four options lettered A to D.”

All around Naomi sat hundreds of students dressed in their uniforms, squeezed into rows of wooden desks. From the open windows, she could hear the voices of classmates whose finals weren’t scheduled until the following day chattering, while students in the nearby science lab were conducting a practical exam. The midday heat was approaching its 105-degree high. Idle ceiling fans hung motionless over the desks, which faced a blackboard that a teacher, probably Mr. Bulama, had ordered a student to wipe clean. In a few weeks, the seniors would gather in this room for the last time and sing farewell to one another with the end-ofyear anthem, “Departure Is Not Death My Sister.” But today was another day of exams.

Naomi was sure that God had finally delivered her into the last chapter of a long struggle. At twenty-four, she was an awkward eight years older than the youngest seniors, and had spent several of her teenage years at home, nursing a lower back pain that the town’s clinic had neither the equipment nor expertise to treat. Friends her age had long ago graduated without her. To slog through the curriculum, she had relied on classmates much younger and had compensated with a protective instinct, issuing instructions and encouragement to her juniors, and sometimes chastising them with a suck of the teeth.

The nickname they called her, Maman Mu, Our Mother, also meant the Preacher’s Wife. It was a subtle tease and a poke at her self-righteous streak. Her favourite singer was a local gospel star, Mama Agnes, whose lyrics called for Christians to keep their faith. Naomi’s extended family included Christians, Muslims, and converts between the two, but by senior year her mind was made up. She told classmates she planned to marry a pastor.

“I’m married to Jesus Christ,” went the chorus of a bubbly, syncopated Mama Agnes song that she knew by heart. “And nobody can separate us.”

Students around her began to work their way through the multiple-choice questions. Her cousin Saratu Ayuba expected to pass with flying colours, as did the class valedictorian, Lydia John. Maryam Ali had studied for months, waking before dawn to shine a torch on her textbooks. Her sister Sadiya just wanted to be done with exams and plan her wedding. This was the class of 2014, schoolmates who had spent years shuffling together between classrooms and the mess hall, the prayer room, and dorms, and whose fates were now set to diverge based on the answers they shaded in front of them. They were on the verge of a new chapter. Although they couldn’t have known it, the first question on the test was an omen.

1. Government protects the lives and property of the citizens of a state through the:

a. courts and the police

b. legislature and prisons

c. ministers and the police

d. customs and the police

EN ROUTE TO CHIBOK, 5:00 P.M.

Malam Abba’s men had packed enough petrol to start several fires but had forgotten to bring enough water to drink. Dozens of his Boko Haram fighters were squeezed onto the back of pickup trucks that same Monday afternoon, trundling in convoy under a baking sun, a jumble of wiry bodies in mismatched uniforms and ragged T-shirts, holding rifles and rocket-propelled grenade launchers. The pickups carved a path along sandy tracks snaking through a stark and desolate landscape interrupted by an occasional tuft of grass or a lonesome baobab. Flanking the trucks was a fleet of motorbikes whose tires struggled to grip, some men riding two or three to a saddle, the cheap engines scraping and sputtering. Their journey had started in a forest camp less than a hundred miles north of their target, driving slowly through the day, then late into the night, bumping across rutted back roads to avoid military outposts or soldiers on patrol.

It was the fifth year that Malam Abba had been waging jihad against the Nigerian state, a government he considered more wicked than all the others in the world. Just one month after escaping from the country’s most notorious jail, the Giwa Barracks, he was free again, leading another operation from the seat of a motorbike that trailed a safe distance behind the convoy. Short and stocky with front teeth that jutted over his lower lip and two long facial marks sculpted under each eye like tear tracks, he was in his late twenties and already a commander, or qaid, and demanded to be treated as such. While his foot soldiers wore tattered secondhand clothes or stolen army fatigues, Malam Abba would go into battle wearing a bulletproof vest over a fresh kaftan and a red cap he called No Sulhu, or No Reconciliation. He was born Abba Mustapha, but he insisted that his three wives and many subordinates address him as a malam, a Nigerian honorific meaning “wise teacher.” In three years and fourteen days, he would be dead from an airstrike, his body shattered by a bomb intended for his leader.

“Allah says the best martyrs are those who fight on the front,” he would tell his men, grizzled veterans and fresh-faced boys as young as thirteen, before an operation. “They are the ones who do not turn back until they are killed.”

These men were waging a war to purge their society of the sins they believed colonialism had brought, especially boko, a Hausa word they used to mean all non-Quranic learning, especially Western-inspired humanistic secular education, which was all haram, forbidden. On some nights they directly confronted the military, driving their trucks in circles around outposts and firing rockets toward soldiers trapped inside. They rode motorbikes into villages suspected of housing so much as a single informant, firing Kalashnikovs in every possible direction. Lately, Boko Haram had begun kidnapping boys as child soldiers, and girls as chattel, packing them onto trucks to be driven into the forest for reeducation. On operations there were always casualties, and before battle, Malam Abba would gird his fighters to lose comrades and to kill. Years in an overcrowded Nigerian prison, where inmates died of cholera and lay on top of each other for lack of space, had redoubled his conviction that his leader, the Imam, was right: unbelievers were collateral damage in a righteous war that needed to be won.

This evening, his unit was driving to a school, but on a mission to steal, not kidnap. They were a looting crew, ordered to find the supplies the insurgency needed to keep its members fed and equipped. Their main target was a rare piece of equipment they had long struggled to find: a brickmaking machine, to construct new houses. Their ranks were swelling, with young men volunteering en masse or being forced to enlist at gunpoint. The new recruits were overwhelming Boko Haram’s forest encampments, where commanders lived in grass huts and had only the branches of tamarind trees to offer as shelter to their foot soldiers.

Information had reached Malam Abba that there was a brickmaker stored at a girls’ school on the edge of a small, mostly Christian town that he had never been to, called Chibok. Boko Haram had a sympathizer on the campus, his comrades would say. His unit knew little about the school and doubted there would be anybody still there after dark. They had a flatbed truck waiting in a nearby village to take home the sacks of food they hoped to find. On the edge of town, there was a small army outpost, a cinder-block garage housing weapons to seize. Malam Abba had prepared for resistance from the detachment of a dozen or so soldiers stationed there, but if those men refused to run, Boko Haram would kill them.

Whatever the case, they would be there by midnight.

THE CHIBOK GIRLS’ SECONDARY SCHOOL WAS MEANT TO BE AN OUTPOST through which Western education spread through Nigeria’s conservative northeast. But it was now almost the last of Borno State’s 1,947 schools left open. For months, Boko Haram’s men had been attacking campuses, torching at least 50 schools and murdering teachers they accused of polluting children with godless knowledge. Educators were shutting their gates. The voices of broadcasters from plastic radios scattered around Chibok’s courtyards had recently begun to report a new horror, terrible enough that residents tried to push the thought of it out of their mind. The militants were kidnapping children. Most of those seized were boys, hundreds of them taken by force. But scores of young women were reported missing as well.

As rumours swelled, Chibok’s parents had debated whether to keep their children in school, and teachers questioned whether to close the campus entirely. After some deliberation, the school’s administration had decided the classrooms should remain open, but only long enough for the students to take their final exams. Faculty had reassured the parents and students that the town was too isolated and too far south for the militants to access. Plus, it was a girls’ school.

Keeping the school open was a calculated risk. If the students missed their exams, they would have to wait an entire year to take them again, and some might drop out. The exam season would be over on May 15, and with prayer, maybe the worst outcomes could be avoided. The girls were braving just forty-five days of tests. And to many parents, the school simply seemed like the safest place for their daughters to be.

CHIBOK, 7:00 P.M.

As the sunset cast shadows through the lead-lined windows of Gana Hostel, one of the seniors picked up a plastic water bucket, flipped it over, and started to beat the twitching rhythm of “A Girgiza Kwankwaso,” a Hausa dance that translated as “Let’s Shake Our Waist.” The day’s tests had ended, and dusk offered a time students could gather in their bustling dorms to relax. Naomi and Saratu rose slowly and began rolling their hips and popping their shoulders to the drumbeat. The two tilted their heads toward each other’s feet and slowly slid into the same pattern. It was a release and a way to suppress the uneasy feeling sweeping a school they knew in their hearts had become unsafe.

Saratu was Naomi’s dearest friend, a first cousin she loved more than all her siblings. They had been close since early childhood, when they would play katezi, a game of trust. Saratu, the younger, would close her eyes, and fall backward. Naomi was usually the one catching and would let her cousin’s tall and slender body get just close enough to the ground so that each time Saratu fell she thought she might collide. Then Naomi would grab her and they would both laugh, and repeat the game. Saratu was quiet and studious, and by senior year, she had begun talking about going to college to become a doctor. “Maybe I could be a nurse,” Naomi would suggest, and then the two could work together.

Naomi, Saratu, and most of the girls taking classes at CGSS lived far enough away that they would spend school nights in one of its four dorms—“Houses,” as in the British school tradition. Naomi and Saratu were in Gana Hostel, a jumble of seventy-two rusting bunk beds, whose iron frames would squeak as girls clambered up and down. There were far more students than beds, which had to be booked in advance.

The dorms were meant to be a safe space for the girls, especially those whose homes were a long walk away. But recently they had become a cauldron of rumour and ghoulish stories about violence that seemed to be edging closer. There had been false alarms. On more than one occasion, girls had run from their dorms in a panicked stampede after a student reported hearing unfamiliar voices at the gate. The collective anxiety was beginning to affect Naomi. She had been having nightmares, and days earlier had dreamed of a group of faceless men chasing her as she tried to climb a wall but fell on the ground. In just a few more days, she would be able to go home, she told herself.

As the darkness fell over Chibok, Naomi, Saratu, and a friend, Hauwa Ishaya, slipped off to the school’s prayer room. The young women sat cross-legged in a circle and took turns:

“I pray for success on my final exams.”

“I pray for my family.”

“I pray for our safety.”

“We put our fate in the hands of God,” said Naomi.

It was getting late and the friends tiptoed back to their bunks, where some of their classmates had already begun to fall asleep while others were shining their phones onto textbooks for a few final hours of reading. Naomi curled up in a corner and dialled her mum to say good night, but the reception was poor and the call couldn’t connect.

Her phone was a battered old Nokia that could only send texts and calls. Scrolling through its contacts, she debated whether to dial Andrew, a boy from the neighbourhood whom she liked. She did. “Why are you staying there?” Andrew asked. “Isn’t it dangerous?”

“They don’t attack girls,” Naomi said, echoing the faculty’s arguments as if they were her own. “Only boys.” Saying it out loud somehow made it better and made the teachers’ reassurances more real.

Naomi wanted to call her mum. The two had fought the day before, and the guilt of upsetting her mum ate at her, but the network kept dropping her calls. Saratu was already climbing into the bottom bunk they shared near the window, a prime location that meant they caught the evening breeze. Students were drifting off, squeezed two to a mattress, some awake but lying silently in the heat. Naomi and Saratu lay there, arms around each other, as their eyelids closed. It was almost midnight when her eyes snapped open.

CHIBOK, 11:55 P.M.

“Gather outside.”

“Don’t worry! . . . We are soldiers.”

The young women filtered into the courtyard and found themselves face-to-face with dozens of young men who they could immediately see were not soldiers. They wore unkempt beards, flip-flops, and tattered uniforms. They stood or paced behind their leader, a stocky man Naomi could see was wearing a red cap.

Malam Abba fired a gunshot into the air and issued a demand to the throng of schoolgirls gathering in front of him, “Where is your brickmaking machine?” The students froze and stared back at him, or at the ground, silent. Malam Abba raised his voice, scanning the crowd for a collaborator. “Find it and we will leave you in your hostel,” he said.

“We don’t know where it is-o!” a student shouted. Another began to lift her arm, but the girl next to her slapped it down. A militant rushed over and pointed his rifle at the first student’s head. “Please don’t kill me,” she cried.

“Anyone who decides to run, we will shoot her!” another man shouted.

One girl spoke up, suggesting they should check the storage depots behind the dormitories. Malam Abba ordered his men to follow her there, as more fanned out across the campus. On the other side of the courtyard, past the crooked guava tree, his fighters were raiding the school cafeteria, hauling away sacks of grain and rice and containers of cooking oil. He could see it wasn’t going to be enough to fill their trucks. “What is in your hostel?” he shouted.

“Our shopping. Clothes, mats,” a student replied. Malam Abba scoffed, unsure whether to believe them. Then several of his men appeared from behind the storage depot with the brickmaker, a tall and cumbersome contraption with a long metal handle to press cinder blocks. They loaded it onto a truck, while others shuttled back and forth from the pantry, gathering the food. The looting was taking hours, as the students stared on. Then, one by one, the men returned to their trucks to retrieve their petrol, each grabbing a yellow jerrican and walking toward a different building. The stream of fuel gargled as it fell from the mouths of the jugs onto the concrete walls. They were going to leave this campus in ash.

Naomi watched, standing in a row of other schoolmates, choking back tears as flames began to climb the walls of her school. The fire ripped through the principal’s office, the teachers’ quarters, the library, the lab, the classrooms, the exam hall, her dorm and the others, then finally the staff office, which was next to where she and the rest of the students were standing. Smoke rushed into her face, filling her eyes with an acrid sting.

The voice of a militant broke her trance. “Shift a little! . . . Don’t you know that the heat is increasing?” The students inched away from the fire, unsure where to go. The men corralled them under a tree where a gunman trained a rifle toward them. “You should say your final prayers,” he said.

He fired the weapon in the air: “Have you finished praying? Lie down.”

The young women began to scramble to hide under one another, each trying to burrow under a squirming stack of bodies. One girl held a sandal against her chest, in tears pleading: “Don’t shoot.”

But now the men were arguing over what they should do with the students.

“Put them into different places and burn them,” one said.

“Let them lead us to their parents’ homes.”

“No,” said another. “Let’s just take them.”

Malam Abba hadn’t come to kidnap these girls. But he could see that his men, after travelling over the course of a day to reach Chibok, were disappointed with the night’s haul. One of his militants was complaining, frustrated with the long distance and meagre returns: “I came with my vehicle empty; I cannot go back with my vehicle empty.”

Malam Abba considered what the Imam would want. This revered place of learning that had stood on the edge of Chibok for more than seventy years was now bathed in orange flame, coughing up smoke. He turned to the crowd and made his judgement. He ordered the hostages to climb into pickup trucks or to walk at gunpoint until they reached a flatbed Mercedes truck.

“Shekau will know what to do with them.”

3

THE PERFUME SELLER

MAIDUGURI MARCH 2014, A MONTH BEFORE THE KIDNAPPING

Abubakar Shekau was supposed to be dead. On two separate occasions, Nigeria’s military had issued statements confirming that they had killed him. But in March 2014, a month before the Chibok kidnapping, the bearded and bellowing leader of Boko Haram reappeared to threaten his countrymen from the one place where the army could never reach him, YouTube. Sitting in front of a golden curtain, wearing a bulletproof vest over a starched white robe and gripping a Kalashnikov in his right hand, Africa’s most wanted man had thirty-seven minutes of angry invective to perform for an online audience.

“In the name of the almighty Allah, killing is my mission now!” he screamed out of the website’s white-panelled video player. “Let’s kill them, my brothers, let’s kill them all!”

Days earlier, Shekau’s men had fought their way into the Giwa Barracks, freeing hundreds of men and young boys, followers and new recruits, from Nigeria’s most infamous jail, an overflowing cellblock so crowded that some of the prisoners running free struggled to restraighten their legs and had to be carried. His video statement was a declaration of victory and a vow to bring more bloodshed to Nigeria. Cackling and screeching death threats, Shekau worked himself into a caricature of rage, pushing his face so close to the camera that the lens struggled to focus. “Just pick up your knives, break into their homes, and kill!”

For five years, Nigeria had been fighting an insurgency whose central riddle was this enigmatic warlord. Abubakar Shekau had grown up a child beggar and perfume seller wandering the same streets of Nigeria’s northeast that he, Boko Haram’s self-declared Imam, was now tormenting. On his orders, teenagers strapped with suicide bombs were detonating themselves in city markets where he had panhandled as a boy. Thousands of militants who had sworn him loyalty were rampaging in Nigeria’s northern states, overwhelming army outposts, dynamiting bank vaults, and breaking hundreds of followers out of prisons. For his cause, children as young as nine were dousing their schools in petrol and burning them down. His hardened face, frozen in a near-wink and a curling grin, looked out onto cities throughout Nigeria from wanted posters plastered on lampposts and government buildings. With murderous ingenuity, Shekau had transformed Boko Haram from an obscure radical sect into a militant army whose war with the government had left thousands dead.

And yet most Nigerians knew very little about him. By 2014, the government was lavishing a quarter of its entire budget to security agencies tasked with capturing or killing Shekau, and still they couldn’t agree on the most basic details of his biography. Intelligence officials argued over whether he was alive, or dead and replaced by a body double. The US government had offered a $7 million reward for his capture, the largest bounty for any terrorist on the continent, but couldn’t say if their target was born in 1965, 1969, or 1975. Commentators in Nigeria’s capital shared rumours that Shekau was living comfortably with his wives across Nigeria’s northeastern border, in Chad, at the behest of that country’s president, or in Libya, or that he was hiding in plain sight, in a mansion in Nigeria’s northeast. Another urban legend held that he’d escaped from a mental asylum before climbing his way to the top of Boko Haram’s militant army. In reality, the fugitive was operating from a hideout somewhere in a remote corner of a forest not too far from the mountainous border with Cameroon, never using a phone and never allowing his visitors to bring one.

On YouTube anyone could watch this mass murderer speak his mind and threaten millions of Nigerians however he pleased. His hourlong video sermons, which would rack up thousands of views, appeared to be the stream-of-conscious ramblings of a madman taking glee in the preceding month’s bombs, jailbreaks, and slaughter, and promising more to come. Jabbing his finger at the camera, he shouted and screeched while gnawing on his miswak chewing stick, the toothbrush used in the time of the Prophet. He threw vitriol at historical figures from the distant past, and to presidents and prime ministers thousands of miles away, from the pharaohs of Egypt to Margaret Thatcher. “It was said that I was killed, but here I am,” he laughed in one video, after the army declared him dead for the second time.

“Obama must be fuming with rage! Queen Elizabeth must be fuming with rage!”

“I am Shekau, the problem child!”

Nigeria’s intelligence analysts couldn’t decide whether he was insane or a strategic genius, or both. Emissaries from the government and the northern Muslim elites had tried to negotiate with him but come back in disbelief. Shekau had demanded that all of Nigeria, Christians and Muslims alike, implement Sharia law as a precondition for talks. One group of community leaders had gone to a distant village near the border with Niger to find a woman who claimed to be his mother and begged her to talk her son out of militancy. She rebuffed them, declaring there was no use trying to reason with her son. “Even his own mother said he was insane,” a security official reported back.

Shekau seemed to relish the attention. “You can see I’m a radical,” he said in one of his videos, flashing a bright and enormous grin. “You should kill me!”

THE MAN WHOSE ARMY WOULD ONE DAY KIDNAP 276 STUDENTS FROM Chibok had something in common with them: his life was defined by a decision to send him away to school. It was 1980 when Abubakar Shekau’s parents sent him to study the Quran, the young boy arriving in the outskirts of Maiduguri, the regional capital, in the backseat of a car with only an uncle as a companion. He was seven years old. Home had been a thatched-roof cottage in a village near the border with Niger, six miles down a dirt track from the nearest main route. Its streets were paved with sand, stamped with the hoofprints and tire tracks of cattle-drawn carts. His mother, Falmata, sold peanuts from a roadside tabletop. Few children went to school or learned how to read. They dashed around, chasing each other across barren grazing land or between picket fences made of sticks bound with wire, until they became old enough to farm. But Falmata could see that her son was brilliant.

Her husband, Mohammad, was an imam, versed in scripture, who would read their child Quranic passages to test his memory. The new parents had been amazed at how much Shekau could recite back, and agreed their son was talented. Yet he was also troubled. Outside the home, he was argumentative and extremely aggressive, a loner who seemed to be living in his own mind. Most of all, he was utterly intractable. Years later, his neighbours would all say the same thing about the young Abubakar Shekau: there was no use trying to reason with such a quarrelsome child. Headstrong was the term his mother would use to describe him.

Her son was born into a national experiment that would leave Nigeria further divided in two. Two decades into its independence from British rule, Nigeria declared public elementary school free. The country’s military government had hoped that even the poorest families from every corner of the country would enrol their boys and girls, forging a new generation of Nigerians who would come of age with a common identity. In some regions, the number of students in school went up tenfold in two years, children of different creeds all learning the Roman alphabet and beginning each morning singing the newly adopted exultant national anthem, “Arise, O Compatriots.” But Shekau’s parents, like many of their neighbours, preferred their child to absorb the tradition and humility of the Al-Majiri schools, where young boys learned the Quran. Some of the best of these schools were located in the place he would come to call home.

The people of Maiduguri liked to say their town was both “the land of a thousand kings,” but also “hotter than hellfire,” and in 1980, the largest city in Nigeria’s northeast was sizzling with the energy of a fast-growing metropolis. Perched near the borders of three countries—Chad, Niger, and Cameroon—its economy turned on the fortunes of smugglers who loaded trucks with kerosene tanks, colourful wax print fabric, car parts, and dried fish from Lake Chad. Maiduguri was once a British garrison post and had been home to just eighty-eight thousand people in 1960, the year Nigeria gained its independence. By the time Shekau arrived two decades later, its population had more than tripled, and the sleepy open-air market town had become a sprawl of cement shops, tin-roofed homes, and whitewashed minarets under a Saharan sun so relentless that locals joked they never used a kettle because water fell boiling from the tap.

The clamour of commerce reverberated through Maiduguri’s sand-heaped alleys, and its commercial boulevard, Babban Layi—Broadway—buzzed with talk and shouts, thwacks of butcher knives, squeaking wheelbarrow tires, and calls to prayer from jousting muezzins. At night, drummers stood under the stars, performing rhythms that drifted into the jail cell of the imprisoned Nigerian band leader and Black Power–inspired dissident Fela Kuti. Boomboxes played cassette tapes of Diana Ross, Stevie Wonder, or the hauntingly beautiful praise songs of Amina Rawaram, “the last Diva of the Sahara,” but also broadcast fiery sermons from radical preachers, local and foreign. Subversive ideas were starting to find an audience in the city nicknamed “the home of peace.”

The year 1980 was the first of a new century in the Islamic calendar and appeared to herald a revolutionary era. In Iran, a turbaned preacher named Ayatollah Khomeini had toppled 2,500 years of monarchy and was implementing the Quran into a constitution for a new Islamic Republic. The Soviet troops crossing into Afghanistan had provoked a young Osama bin Laden to join a resistance movement that would ultimately use the language of jihad to wage war against a superpower. These events felt far away yet somehow close to a pious, landlocked city across the Sahara.