13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

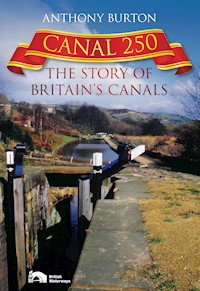

When a young English nobleman was thwarted in love he abandoned the court, retired to his estate near Manchester and built a canal to serve his coalmines. The Bridgewater Canal was the sensation of the age and led others to follow the example of the enterprising Duke of Bridgewater. From his starting point in 1760, over the next half-century Britain was covered by a network of waterways that became the lifeblood of the Industrial Revolution. This is the story of 250 years of history on those canals, and of the people who made and used them. The book tells of the great engineers, such as Telford, Brindley and Jessop and of the industrialists, such as Wedgwood and Arkwright who promoted the canals they built. It also tells the story of the anonymous navvies who dug the canals, the men and women who ran the boats and the workers who kept the canals running. Covering the entire history of the canal network (from the glorious early days, through the years of decline caused by rail and then road competition, up to the subsequent revival of the canals as leisure routes), this wonderfully illustrated book is a must-have for all canal enthusiasts.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

ANTHONY BURTON

First published 2011

The History Press The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved © Anthony Burton, 2011, 2013

The right of Anthony Burton, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9462 3

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Introduction

1 The Father of Canals

2 The Brindley Years

3 The Broad Canals

4 The New Men

5 Men at Work

6 The Working Canal

7 The Craft of the Waterways

8 The Carriers

9 The Boating Community

10 A Second Start

11 Passengers and Pleasure

12 A Period of Change

13 Restoration

14 Canals Today

15 Looking to the Future

Gazetteer

INTRODUCTION

IN OLDER history books the year 1760 is notable as the year George III came to the throne. In more modern books it has a far greater significance than just adding another I to the list of Georges. It is the date that is conventionally taken as marking the start of the Industrial Revolution. An essential part of that great social and technological upheaval was the transport route that was to bring in the raw materials and carry out the finished products of the new industries – the canals. In 1760, the Act of Parliament was passed that authorised the construction of the Bridgewater Canal, and that had a very special significance. It was the first canal in Britain that was independent of any natural waterway; and marked the beginning of the Canal Age, which saw a watery web stretch from Cornwall to the Highlands of Scotland. This book is a celebration of that achievement.

Anyone who writes about canals today owes a debt to those who went before. My own interest in canals was sparked by nothing more than going on holiday, but I was fascinated by the structures I saw along the way and, in particular, by the awe-inspiring Pontcysyllte aqueduct. I wanted to know more, and in particular I wanted to know about the man who was credited with building it, Thomas Telford. I read L.T.C. Rolt’s biography, which gave a vivid picture of the life of the great engineer. It was the first time that I had even considered that engineering could be as much about personalities as practicalities. It was a revelation. I also acquired Eric de Maré’s The Canals of England. What impressed me about that book was the way in which it showed the rich texture and fascinating contrasts of the waterways. In particular there were pictures of the lock staircase at Grindley Brook, which I had passed through on my journey along the Llangollen. At the time, I had been too busy trying to work out how to operate three interconnected locks to worry about much else. These photographs opened my eyes to the way in which the visual pleasures of the locks was dependent on details such as the contrast between the massive stones of the lock walls and the pattern created by the brick ridges on the ramp. In de Maré’s own words: ‘they achieve something supreme in utilitarian beauty’. I would certainly not quarrel with that. Shortly afterwards, I began to take a keener interest in the history of canals and inevitably had to turn to the work of Charles Hadfield. No one had ever attempted to write a comprehensive history of the canals before that and, even now, I can still marvel at the huge effort involved in his pioneering work. These three authors represent three strands of the story: the human story in Rolt, the physical story in de Maré and the detailed documentary history in Hadfield. The three approaches may be different, but each is valid and valuable and each has been influential in my own work.

Over the years I have spent countless hours in archives and I have always thought of this part of the work as a treasure hunt. You spend a vast amount of time digging around and occasionally you strike gold. Most official documents can be dry stuff, but there are nuggets in there that make the whole search worthwhile. There are even some real discoveries to be made. Years ago, working in what was then the British Transport Historical Record Office at Paddington, I ordered up one of those files you open more in hope than expectation. It was simply labelled ‘Miscellaneous’, but inside I found handwritten letters from Thomas Telford, which seemed never to have been catalogued. There is nothing quite like holding original letters to give you a sense of connection with the past. While researching in libraries and archives I was helped by the work already put in by Charles Hadfield, which made my own life so much easier – and was very conscious that he had set a high standard of meticulous research. But I was also always on the lookout for the little detail that brought the human story alive, in the way that Tom Rolt has done so magnificently in so many books. I remember coming across an entry in one of the Committee books of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal Company, recording the death of a workman in a fall of earth. He was simply described as ‘a stranger called Thomas Jones supposed from Shropshire’. The phrase seemed to sum up something very important about the life of the navvy. To his employers he was no more than one unit in an anonymous army. I wanted to look behind the anonymity and find out more about these men, whose Herculean labours created the canals.

The story of canals is not just to be found in old records and documents; it is also written on the landscape. Much as I have enjoyed archive research, I have to confess that I have had even more pleasure from seeing the canals themselves. I have always contended that there is no real substitute to travelling them by boat. That way, you not only see how things work, you experience them directly. But you also have to learn how to look and understand the significance of what you see. That was something I had learned from Eric de Maré.

This book comes after decades, during which I have travelled all over Britain looking at canals; boating those that are navigable and tramping the countryside, hunting out the remains of some that are all but forgotten. In everything I have done, however, I have always been conscious of the work of those three great pioneers who first enthused me and taught me how to see and investigate the canal heritage. They remain an inspiration and without their pioneering efforts this survey of 250 years of canal history would never have been written.

The author would like to thank British Waterways for providing funding for the illustrations for this book, and the following for supplying the pictures (illustrations not listed are from the author’s collection):

Illustrations on page 16, National Railways Museum; 19, 25, 34, 38, 39, 41, 45, 52, 54, 57, 59, 66, 68, 69, 72, 73, 78, 80, 84 (Bottom two), 86, 89, 91, 93, 97 (Top), 98, 100, 103, 107, 111, 114, 118, 120, 123, 125, 128 (Bottom), 134, 138, 141, 149, 150, 153, 160 (Bottom), 171 Waterways Trust; 22 (Left), 29, City Museum, Stoke-on-Trent; 22 (Right), Josiah Wedgwood & Sons Ltd; 24, National Portrait Gallery; 56, A.D. Cameron; 166 (Top), 168, Cotswold Canals Trust; 174, British Waterways.

1

THE FATHER OF CANALS

FRANCIS EGERTON, third Duke of Bridgewater, was a most unlikely candidate for the role as leader of a transport revolution. Nothing in his early life suggested or hinted at what was to come. It is true that the Egerton family had a fine tradition of public service behind them. His great-great grandfather, Sir Thomas Egerton, had been Lord Keeper of the Seal during Elizabeth I’s reign; his great grandfather John Egerton, the first Earl of Bridgewater, had been a famous patron of the arts, and his own father was the first Duke. Francis was born in 1736, one of five sickly boys, four of whom died young. His early life was made even worse by the death of his father in 1745. His mother remarried within the year, to a man half her age, and seems to have taken little interest in his welfare – his new stepfather even less. He was considered to be rather stupid, if not almost imbecilic, and scarcely worth bothering about. His elder brother had inherited the title and Francis could be left to his own devices, since nothing was expected of him. All that changed in 1748, when his elder brother died, and he was no longer merely young Francis: he was the third Duke of Bridgewater. A younger son could be safely ignored, but not a Duke. His parents’ first thoughts were to declare him unfit to hold the title, and they refused to pay for his education. It took a court case to settle that. Inevitably, the boy was deeply unhappy, ran away from home, and did what many teenagers have done down the years in similar circumstances. He started drinking. Something had to be done. He would need an education to prepare him for his place in the aristocratic world. There was a well-established method available for the young man – he must go on The Grand Tour, accompanied by a personal tutor. There he would learn refinement and manners and pick up an appropriate smattering of classical culture.

The young Duke’s mentor was no ordinary teacher. Robert Wood was one of the foremost archaeologists of the day, among the first to apply a scientific approach to excavation and measurement of sites. He had spent a good deal of time working among the Hellenic and Roman remains of Palmyra and probably had little enthusiasm for trailing around Europe with a bored, drunken teenager. But he needed the money. So the scholar and the Duke set off to tour the usual sites, starting in Paris, and Wood’s worst fears were soon realised. His young charge continued his drinking and pursued a French actress. It was all very scandalous. Wood whisked the Duke off to safer ground, visiting the sites of the ancient world and encouraged his young student to purchase a number of antiquities along the way, which were eventually crated up and sent off to the family home in Lancashire. It is an indication of the Duke’s enthusiasm that, it is said, he never bothered to unpack them. At least he picked up enough sophistication and knowledge to make him presentable for an appearance in the English Court.

The famous portrait of the young Duke of Bridgewater, pointing to the Barton aqueduct.

The case for canals: one horse pulling a boat could carry the entire load of this team of pack-horses.

The entrance to the mines at Worsley.

There is a famous portrait of the Duke taken just a few years later, when he was in his twenties, that shows a very handsome and elegant young man, fashionably dressed and almost foppish. He was, at this time, very much the man about town, enjoying horse racing and gambling, and he must have had an air about him, for he successfully wooed one of the great beauties of the day. Elizabeth Gunning and her sister Maria were born into a very impoverished but aristocratic Irish family. Their mother thought seriously of putting them on the stage, but decided instead that they might do rather better for themselves in the more profitable marriage market. They appeared at the Court in borrowed clothes, but their exceptional good looks more than compensated for the lack of fortune. They were painted by Reynolds and had soon acquired husbands: Maria married the Earl of Coventry and Elizabeth became Duchess of Hamilton. Maria’s marriage was short lived. Her husband died and it was as a widow that she met and was courted by the young Duke of Bridgewater in 1758. The Duchess and her sister were everything that the young man was not, sophisticated and worldly. But it was one thing for a young buck to have his fling – a future Duchess was supposed to behave very differently. He was now alarmed to hear rumours about the immoral behaviour of the Countess of Coventry. He promptly demanded that her sister should agree never to see her again as a condition of his marriage. Maria, not surprisingly, refused this rather ludicrous request. The match was over. The Duke left London in 1758 and renounced the company of women for ever. It was not just a case of not getting involved in any more romantic entanglements: he refused even to allow female servants in his house. He set off for his estates at Worsley, near Manchester, and threw himself into the industrial world.

It seems somewhat odd to us today to think of aristocrats engaging actively in industry. But the mid-eighteenth century saw the first stirrings of the Industrial Revolution and it was clear that one commodity would be increasingly profitable. The burgeoning iron industry was already using coke instead of charcoal in its furnaces. In a rural economy, there was wood for the fires in the surrounding countryside, but the growing towns needed a very different source of fuel for heating and cooking. Everyone needed coal. Many noble families began to realise that what lay deep under their grounds might be worth more than anything that might grow on the surface. The Duke of Bridgewater was one of the lucky ones: he had his own mines just up the road from his home in Worsley. There was just one problem: how to get the coal from the mines to Manchester. This was a town that was growing at a phenomenal rate. In 1717, the population had been around 8,000, now in 1757 it had risen to around 20,000. These would be his customers and they were rather less than 8 miles away.

This might not seem much of a difficulty: put the coal in carts, harness up the horses and away you go down the road. The road, however, was the problem not the solution. In the middle of the eighteenth century roads varied between bad and wretched. Under the old system of highway maintenance, the local people were charged with keeping the roads in good order. Citizens were supposed to give up a certain amount of time a year to repairing damage. In practice, those who could afford to do so, paid others to go in their place, while the unpaid did as little as possible. Improvement was supposed to arrive with the turnpikes. These were superior and travellers had to pay tolls to use them. The trouble was they were seldom much better than the older versions. The Turnpike Trustees generally farmed out the work of maintenance to whoever put in the lowest bid and sat back to enjoy the profits. Lowest prices generally went with shirked responsibilities. Eventually, things deteriorated to the point where the Trustees found themselves bound to act. A contemporary described the process: ‘A meeting is called, the Farmer sent for and reprimanded, and a few Loads of Gravel buried among the Mud, serve to keep the Way barely passable.’

Arthur Young, who travelled around Britain reporting on the state of agriculture in the 1760s, had this to say about a Lancashire road:

Let me most seriously caution all travellers, who may accidentally purpose to travel this terrible country, to avoid it as they would the devil; for a thousand to one but they break their necks or their limbs by overthrows or breaking downs. They will here meet with rutts which I actually measured four feet deep, and floating with mud only from a wet summer; what therefore must it be after a winter!

And this was the new Wigan turnpike. It is not hard to imagine what it must have meant for a team of horses trying to haul a loaded wagon through such a morass. Things looked very different, however, if the same load could be carried in a boat. Engineers did tests later in the century and found that the maximum load that a horse could pull on a wagon over what was euphemistically described as ‘a soft road’ was little more than half a ton. But if they set that same horse to pull a barge on a river, it could move 30 tons.

The actual figures may not have been available to an earlier generation, but it was a matter of simple observation that river transport was quicker and more economical than road transport. As a result, the rivers of Britain had been steadily improved for centuries. The biggest change came with the introduction of what were known as ‘pound locks’, though later we dropped the pound part and simply called them locks. The idea is simple. Natural rivers have an unfortunate tendency to behave in a very irregular fashion – sometimes they wander along placidly, then they will suddenly make a bit of a dash downhill in rapids and shallows. To overcome that problem, the river engineers arranged for boats to travel up and down in a series of controlled steps. Weirs were built across the river to create deep water. An artificial cutting was then constructed to bypass the weir, with a lock to overcome the difference in levels. The very first wholly modern lock in Britain was built on the River Lea in the sixteenth century, an event that was considered so important that it was described in a poem of 1577, ‘Tale of the Two Swannes’. It may not be great poetry, but at least it tells us something about the technology:

The Canal du Midi inspired the Duke: the impressive lock staircase at Fonserannes.

… the locke

Through which the boates of Ware doe passe with malt,

This lock contains two double doors of wood,

Within the same a cesterne all of Plancke,

Which onely fils when boates come there to passe

By opening of these mightie dores.

This is clearly a timber-sided lock, with double doors. These must have been mitred doors, meeting at an angle, otherwise there would have been serious leaks. It seems an obvious thing, but they had to be invented in the first place and the man responsible was no less a person than Leonardo da Vinci. He may be famous as one of the world’s greatest artists, but in 1482 he was the official engineer to the Duke of Milan. It was during this period of his life that he introduced the mitred gates for locks on the Naviglio Interno.

By the time the Duke of Bridgewater came to think about transport, river improvement had gone just about as far as it could go, but that still left areas that were some distance from the nearest navigable waterway. Unfortunately for him, Worsley was one of them. But if the Duke had forgotten everything he had learned about classical ruins since returning from his European jaunt, there was one memory that remained with him. He had visited the Languedoc Canal, now known as the Canal du Midi, in France.

This extraordinary canal was designed and constructed under the direction of Pierre-Paul Riquet. He was not an engineer, but a man who had the highly lucrative job of collecting the salt tax. The canal was designed to link the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, but there was one immediate problem that had to be solved. The canal had to cross a watershed, which meant that it had a summit from which water would drain down in two directions. If it was not constantly supplied with water it would simply dry up. Riquet found the highest point along the route and searched for the nearest water supply. He found it miles away in the Montagne Noir region, so his first task, when work began in 1666, was to build reservoirs and join them to his proposed canal by water channels, the rigoles. The first of these, the Rigole de la Montagne ran for 25km and was a major undertaking, but it was as nothing compared with the works on the canal itself.

This was a canal intended to take seagoing vessels, so the locks had to be big, with chambers 30m long and 5.6m wide. There were ninety-two of them altogether, and to save water and time for the boatmen, many were grouped together into staircases. In these, the top gates of the lower lock also form the bottom gates of the one above. Riquet built twelve double locks, four triples, one quadruple and it all reached a stupendous climax in the magnificent sevenlock staircase at Fonserannes. He crossed one river on an aqueduct and at Malpas – the ‘bad step’ – he took his canal through the hill in a tunnel. Almost a century before the Duke of Bridgewater began to think about waterways, Riquet had solved nearly all the major problems that future canal engineers could expect to face.

Here was the answer to the Duke’s dilemma: he could build a canal to take the coal from his mines to Manchester. Among the Duke’s most trusted employees were two brothers, Thomas and John Gilbert. Thomas was the Duke’s Agent and his brother took a keen interest in the mines. We shall never know who came up with the first idea of canal building, but it was undoubtedly John Gilbert who had the largest say in the original plans. Most mines suffer from a problem with water that needs to be drained constantly to keep the workings dry. Gilbert’s ingenious idea was to turn the problem into a solution. He devised a system in which the unwanted water would feed a system of underground canals that would reach to the coal faces and eventually emerge as a navigable waterway, heading off to Manchester.

To build a canal required an Act of Parliament and the Duke put in his application. It was approved in 1759, but with so many qualifications as to make it of comparatively little value. He could get as far as the River Irwell at Barton, and to continue his watery journey he could have made a connection with the river for the rest of the way. But the river authorities were having none of that. They had a valuable monopoly on trade and did not welcome interlopers. If the Duke wanted to use the river, he would have to pay large tolls – which rather defeated the whole object. He could not use the river and ensure his profits and it represented a barrier to further progress. At this stage another important character appears on the stage. Gilbert had been very impressed with a neighbour of his, a Derbyshire millwright called James Brindley, who had shown great expertise in managing water, when he had been called in to drain the aptly named Wet Earth Colliery. He was now recruited as canal engineer. Together, the Duke, Gilbert and Brindley came up with an altogether more ambitious scheme. If they could not join the Irwell, then they would vault over it. They would carry the Bridgewater Canal across the river on an imposing aqueduct. A new Act was passed in 1760 and now work could begin on the first canal in mainland Britain that took a line independent of any natural waterway.

Barton aqueduct; the print emphasises the monumental abutments.

The Act attracted very little attention at the time, but it marked the beginning of over half a century of canal construction that was to see the network develop right across the face of Britain, in the greatest period of civil engineering since the Romans built their roads.

It was one thing to get the Act of Parliament, but quite another to find the money to build a canal. This was a private venture and the Duke had to find the funds himself. He was a wealthy man but even he lacked the resources for such an enterprise. The first thing to go was the London house – he had no intention of ever again venturing into London society. Then he mortgaged his estates and after that he was forced to borrow money, first from relatives, then from Child’s Bank. Even then, he was constantly short of funds. On one occasion, he was pursued by the local parson trying to get payment for a debt and was embarrassingly tracked down, hiding in a hay loft. It has to be remembered that he was still in his twenties, and there must have been many who condemned him as a flighty young nobleman, who was letting ambitions exceed the bounds of plain common sense. There was no shortage of so-called experts to denounce his folly. Although aqueducts were not new – the Romans had famously built them for water supply and Riquet had already made navigable aqueducts in France – there were still sceptics who doubted if such a scheme could succeed. An allegedly expert engineer, called in by the Duke to offer a second opinion, simply remarked that he had heard of castles in the air, but this was the first time he had heard of one being built. It is to the great credit of the Duke that he ignored the pessimist and went ahead with his plan.

There has always been doubt and controversy over who should take the credit for designing and building the great aqueduct over the river at Barton. There are arguments in favour of both Brindley and Gilbert as being the leading figure, but as there is no doubt both were deeply involved in the project it is probably as well to let them share the credit. It is, however, notable that Brindley never attempted anything quite so bold again, but then he never again had to build an aqueduct over a navigable river. The structure was carried 38ft above the river on three arches that had to be high and wide enough to let the river craft pass safely underneath. Bridges of these dimensions were not unusual, but a bridge and an aqueduct are not the same. The latter, like the canal itself, has to be made watertight. This involved ‘puddling’, pounding a suitably dense clay with water until all the air had been forced out, leaving a uniform mass of material that could be spread out as a waterproof lining. The usual tool for pounding the mixture was the heavy boot of a workman – and stomping up and down all day in this cloying mess must have been exhausting.

Although it was not recognised as such at the time, the Sankey Brook was arguably Britain’s first true canal.

When the great day came to fill the aqueduct with water, it seemed that the sceptics might be right after all. One of the arches began to give way and the water was quickly drained off again. Brindley did what he often did in times of stress – he took himself off to bed, which was not particularly helpful, leaving Gilbert to solve the problem. It was soon obvious that Brindley, who was naturally cautious, had been overly so in this case, piling on the clay puddle to a great depth. It was the sheer weight of the lining that was causing the problem. Gilbert got his men to remove tons of the puddle and on 17 July 1761 the water was let back in. This time there was no problem and the first barge, carrying 50 tons of coal, was hauled across. It was a triumph!

The aqueduct was the sensation of the day, drawing scores of tourists, who came to marvel at this ‘canal in the air’. One visitor almost succumbed to a fit of the vapours at the sight:

Whilst I was surveying it with a mixture of wonder and delight, four barges passed me in the space of about three minutes, two of them being chained together, and dragged by two horses, who went on the terras of the canal, whereon, I must own, I durst hardly venture to walk, as I almost trembled to behold the large River Irwell underneath me.

Georgian tourists were notoriously given to exaggeration; surely the poor, fainting gentleman must have seen a bridge crossing a large river. The quote does, however, give a hint of the excitement caused by this venture. Accounts appeared, not just in the local press, but also in London publications such as the Gentleman’s Magazine. Other observers took a much more practical view of things:

The difference in favour of canal navigation was never more exemplified nor appeared to full and striking advantage than at Barton-bridge in Lancashire, where one may see, at the same time, seven or eight stout fellows labouring like slaves to drag a boat slowly up the river Irwell, and one horse or mule, or sometimes two men at most, drawing five or six of the duke’s barges, linked together, at a great rate upon the canal.

To be fair, this is a very partisan account by John Phillips, a propagandist for canals, and rather overlooks the fact that had the Irwell barge been going downstream, life would have been much easier for the boat crew. The real contrast was not with the river, but with the roads and here it was even more striking.

The canal was not, however, quite the pioneering marvel that people seemed to think. Ignoring what had happened in France – and the British were happy to ignore anything foreign – there had been canals built in Ireland and an important scheme had begun not far away in 1755. The Sankey Brook Navigation was a canal in all but name. The Act was nominally ‘for making navigable the River or Brook called Sankey Brook … in the county Palatine of Lancaster’. It attracted little attention, simply because it was seen as just another river improvement scheme. In practice, it consisted entirely of an artificial canal, and should by rights be applauded as the true beginner of the canal age. It would have been had anyone taken any notice. But its promoters realised that, if they had advertised the fact that they were doing something really radical, they might have attracted opposition. So they hid their intentions away by using the familiar language of river improvement. The Sankey Brook crept up on the world unnoticed. The Bridgewater Canal appeared with a dramatic flourish. It was the castle in the air that got the world talking.

A sketch by Arthur Young, the travel writer, shows one of the small aqueducts on the Bridgewater Canal and also gives a good idea of the wretched nature of the road it passes over.

The canal was working and the aqueduct proclaimed loud and clear that natural obstacles need not hamper the spread of canals. What very few noticed was that the aqueduct was only one part of a complex system. There was far more canal underground than appeared on the surface. In time, the system of underground waterways in the mine was to stretch for nearly 50 miles, working at many different levels. An American traveller, Samuel Curwen, visited Worsley in 1777 and was taken on a tour of the underground workings:

We stepped into the boat, passing into an archway partly of brick and partly cut through the stone, of about three and a half feet high; we received at entering six lighted candles. This archway, called a funnel, runs into the body of the mountain almost in a direct line three thousand feet, its medium depth beneath the surface about eighty feet; we were half an hour passing that distance. Here begins the first under-ground road to the pits, ascending into the wagon road, so-called, about four feet above the water, being a highway for the wagons, containing about a ton weight of the form of a mill-hopper, running on wheels, to convey the coals to the barge or boats.

Special boats had been devised to reach the coal face. They were long and narrow, just 4ft 6in wide, and known as starvationers, because they were very skinny and their ribs showed. There was an equally ingenious system at the Manchester end of the canal, at Castlefield wharf. The coal had to be lifted to a higher level, so Brindley devised a system where the boats could be floated under a shaft. A crane, worked by a waterwheel, then lifted the coal to street level.

The whole canal was efficient and that efficiency was reflected in cheap carriage costs, which halved the price of coal in Manchester. Now the Duke was ready for an even more ambitious plan, to extend his canal to reach the Mersey at Runcorn. This would provide a link between two towns that were both developing with the growth of industry: Liverpool, the rapidly expanding port and Manchester, which was destined to become Cottonopolis, the heart of the cotton industry. There was intense opposition from the river authorities, but the Duke received his Act. However, difficulties in construction were not so easily overcome.

River crossings were simple compared with the problems faced at Barton. The land was flat, the rivers carried no traffic, so plain low structures were all that was needed. Then the engineers met an area of peaty bog, known as Sale Moor. As fast as the men tried to dig the canal, the mud simply oozed back in again. The problem was solved by digging trenches, and then lining them with timber baulks which were then fastened together to form parallel walls to keep the mud at bay, while the canal bed itself was excavated between them. The other problem was the crossing of the valley of the River Bollin, which called for a massive earth embankment. Although many came to wonder at Barton aqueduct, in strictly engineering terms building a high, stable embankment represented a far greater challenge. The final obstacle came with the arrival of the canal at Runcorn. Up to then it had been a broad, lock-free waterway, but now a flight of locks had to be built. It was essential that they could take the Mersey flats, the traditional barges of the river, and these were 72ft long and 14ft 9in beam. It was a huge effort and Brindley was not to live long enough to see it completed.

An unusual feature of the Bridgewater was an early form of containerisation – boats carrying boxes designed to fit snugly into the hull.

The Duke was fortunate in one respect, that he could use his own workers and employees in the task. Samuel Smiles, in his Lives of the Engineers, written over a century after the work was completed, gives one of the very few accounts of who these men were and what they were like:

In Lancashire proper names seem to have been little used at that time. ‘Black David’ was one of the foremen employed on difficult matters, and ‘Bill o Toms’ and ‘Busick Jack’ seem also to have been confident workmen in their respective departments. We are informed by a gentleman of the neighbourhood that most of the labourers employed were of a superior class and some of them were ‘wise’ or ‘cunning men’, blood-stoppers, herb-doctors, and planet-rulers, such as are still to be found in the neighbourhood of Manchester. Their very superstitions, says our informant, made them thinkers and calculators. The foreman bricklayer, for instance, as his son used afterwards to relate, always ‘ruled the planets to find out the lucky day on which to commence an important work’, and, he added, ‘none of our work ever gave way’.

The Bridgewater canal system was an engineering triumph, but more importantly, as far as possible future investors in canals were concerned, it was a commercial success as well. Accounts for the later years of the canal must have made very satisfactory reading for the Duke who as a young man had risked so much. The income from the mines and the canal eventually amounted to almost £70,000 a year, the equivalent of several millions today. It is always difficult to interpret figures from another age, so to put that in some sort of perspective, it is worth looking at events that were to lead eventually to a news story that appeared in 2008. It is a vivid demonstration of the purchasing power of a gentleman on an income of £70,000 per annum.

Philippe, Duc d’Orleans, the nephew of Louis XIV, had assembled a magnificent collection of artistic masterpieces. In the 1790s his life, like that of every French aristocrat, was turned upside down by the Revolution. In order to try and build a new life, he decided to send his whole collection, of 305 paintings, for sale in London. The problem was that London was full of French aristocrats selling off their treasures: there were a glut on the market. The Duke of Bridgewater may have known little about art but he knew what he liked – he loved a bargain. He got together with his nephew Lord Gower and the Marquis of Carlisle, and together they bought the whole lot for £43,000. They’d managed to purchase over 300 Old Masters for less than the annual income from the Duke’s industrial interests. And that’s not the end of the story. The three then picked out the best of the bunch to keep for themselves. They selected ninety-four works and put the rest back up for auction; they fetched £42,500. So what did the Duke get himself for, in effect, his share of the outstanding £500? He finished up with some rare prizes: three Raphaels, four Titians, a Rembrandt self-portrait and eight Poussins. Some bargain! The story now moves forward in time.

Because the Duke died childless, the Bridgewater Collection went to the descendants of his sister, who had married the Duke of Sutherland. In later years, important paintings were sent on loan to the National Gallery of Scotland. In 2008 the present Duke of Sutherland decided to sell two of the most famous works, a pair of Titians, and offered them to the Gallery at what in the art market is considered the bargain price of £1 million pounds. Even given the huge value placed on Old Masters today, it is clear that the Duke’s annual income made him a very rich man indeed.

In his later years, the Duke changed from the lithe young man dressed in style to one who was ‘large and unwieldy, and seemed careless of his dress, which was uniformly a suit of brown’. He looked so little like an aristocrat that on one of his visits to Castlefield wharf, a workman called him over and asked for a hand loading coal into his barrow. The Duke duly obliged. He was a compassionate man: ‘During the winter of 1774 the Duke of Bridgewater ordered coals to be sold to the poor of Liverpool in pennyworths, at the same rate as by cart loads. Twenty-four pounds of coal was sold for a penny.’ His canals remained the great love of his life. On one of his rare visits to London, his gardener took the opportunity to beautify the grounds, planting extensive flowerbeds outside the windows. He did not get the response he expected. The Duke was livid; the blooms obstructed the view of the canal. He took his stick and demolished the lot: flowers came a very poor second to waterways.

The year 1760 has been traditionally taken as the starting point of the Industrial Revolution, and the start of work on the canal at Worsley is one of the key events. No doubt canals would have been built anyway; they were obviously of immense value to the developing industrial world. But someone had to take the first, bold step – and when that someone was prepared to risk his entire fortune on the venture, then he deserves to be known as ‘The Father of Canals’. He died in 1803, after a road accident, by which time he had had the satisfaction of seeing his beloved canals spread throughout the land. He was buried among his ancestors at Little Gaddesden, and his memorial reads: ‘He sent barges across fields the farmer formerly tilled’; not very romantic perhaps, but one feels that the Duke would have heartily approved.

2

THE BRINDLEY YEARS

IT IS difficult to appreciate the impact made by the opening of what now seems a modest canal from Worsley to Manchester, but at the time it was a sensation, and nowhere was its impact felt more strongly than in the newly developing industrial world. Britain was at the start of a period of rapid transformation. Work that had once been done by hand was now being performed by machines. Craftsmen working in their own homes or in small workshops were being replaced by wage earners in factories and mills. Villages were growing into towns; towns would become cities. The new world needed a new transport system, and it had found just what it needed: canals. It also needed experienced engineers to oversee their construction. It was inevitable that canal promoters would turn to the men who had built the Bridgewater Canal, but the Gilbert brothers had very successful careers working for the Duke of Bridgewater and saw no reason to change. That just left one man: James Brindley. James Sims, author of the Mining Almanack for 1849, looking back on this period, wrote, ‘Amongst all the heroes and all the statesmen that have ever yet existed none have ever accomplished anything of such vast importance to the world in general as have been realised by a few simple mechanics.’ It was just such men as James Brindley that he had in mind.

Brindley was born at Tunstead near Buxton in Derbyshire in 1716, but later moved to a farm near Leek in Staffordshire. We know very little about his early years. Samuel Smiles, who wrote biographies of many of the leading engineers of the eighteenth century, described Brindley’s father as being a dissolute character, who did little for his family. But we do know that the boy must have received a rudimentary education, as some of his notebooks have survived. His spelling seems to have been entirely phonetic, and you can hear his local accent in the way he wrote. While working on an engine, he began with ‘Bad louk’, which improved to ‘Midlin louk’ and ended with the triumphant ‘Engon at woork’. At the age of seventeen he was bound as apprentice to a wheelwright and millwright, Abraham Bennet of Sutton near Macclesfield.

Millwrights were the foremost mechanical engineers of the day, expected to turn their hands to the design and construction of many different types of machinery. There was another aspect of the work that was to have a vital impact on Brindley’s later career: the millwright had to understand how to manage watercourses. In theory, the apprenticeship was a system in which the young man would learn the trade under the careful supervision of the master. Unfortunately, in this case, the millwright was often drunk and the journeyman was usually away. Not surprisingly, Brindley was regarded as something of a bungling incompetent, simply because no one had actually taken the time to teach him. So he set about a process of self-education, watching and copying others and learning from his own mistakes. It seems that at the very beginning of his career he had decided that if he wanted to know how to do something well, then he would be better off relying on his own resources and common sense rather than alleged experts. It was an attitude that was to stay with him throughout his life.

James Brindley posing with his surveying instrument.

The eminent potter Josiah Wedgwood, the chief promoter and first treasurer of the Trent & Mersey.

The benefits of all his hard work appeared when he was first employed on his own as a millwright for a small silk mill near Macclesfield. The bungler proved that he had mastered his trade. It is difficult to disentangle myth from fact when looking at the early life of a man destined to become famous. John Phillips in his book Inland Navigation, written in 1805, idolised Brindley as the first, great canal engineer. He recounted this story of his early days. Bennet was commissioned to build a paper mill – something he had never attempted before and word got about that he was making a hash of it. So Brindley took it upon himself to put things right. He set off on a Saturday morning to walk 50 miles to the nearest existing paper mill. There he inspected all the machinery, memorised the details and walked home again, ready for work on Monday morning. After that he was able to ensure that work on the new mill was carried out to everyone’s great satisfaction. It is a good story, but highly implausible. Even if you accept that anyone could walk a hundred miles in a weekend, and still find time to work out the technical details of a complex mill, it still doesn’t ring true. The working machinery of the mill would have consisted of heavy hammers, powered by a waterwheel, which pulverised the rags used in paper making. Such giant hammers were commonplace and had been in use for centuries, in the fulling mills of the textile industry and in forges. No millwright could have been unaware of what was needed. What is clear, when the exaggerations have been swept away, is that Brindley was perfectly capable of rescuing the incompetence of the increasingly drunken Bennet. At least his master had enough sense to retire to his bottle and leave the young man to get on with running the business. When Bennet died in 1742 Brindley set up on his own, in Leek.

He soon established himself as being something more than a mere millwright. By now a new source of power had appeared in the land – the steam engine. The early engines, based on a design by Thomas Newcomen, were exclusively used for pumping, mainly from mines. Brindley went to see one of these new engines at Wolverhampton in 1756 and typically decided to build one himself, but using his own ideas. Bizarrely, he chose to construct it with a wooden cylinder and was sufficiently pleased with the result to patent it. No one ever repeated the experiment. But his growing reputation as an ingenious worker meant that people with problems were often knocking on his door. One such problem occurred at the Wet Earth Colliery near Manchester. The problem is contained in the name – water, and how to get rid of it. Brindley’s solution was to install a pump, powered by a waterwheel, but he needed the water to power it. He had to take it from the Irwell, down an 800-yard channel to a point opposite the adit that gave access to the mine. Unfortunately, it was only possible to construct the channel on the opposite bank of the river to the mine, so he took the water underneath the river in an inverted siphon. Now it could be fed to the waterwheel to work the pumps. It was an immediate success – the mine was drained and became a highly profitable concern. It had an even more important consequence for Brindley: it brought his name to the attention of the Gilberts and launched him on his career as a canal engineer. But before that happened he had already made another important connection.

In 1750, he set up a second business at Burslem, in the heart of the Potteries, leasing the premises from the Wedgwood family. John and Thomas Wedgwood were, like other Staffordshire potters, starting to use powdered flint in their ware. The traditional earthenware of the district was made from a dark clay, that could either be disguised under a heavy white glaze or decorated by slip, creating patterns using a semi-liquid clay, rather like adding icing to a cake. It had been discovered that by adding flint to the clay before firing, a far paler product could be obtained. But in order to get the powder, the flints had first to be calcined, heated to a high temperature in a furnace, and then crushed in a mill. This was a potentially profitable business for a millwright. It was, however, to be one of the next generation of Wedgwoods who was to transform the industry.