18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

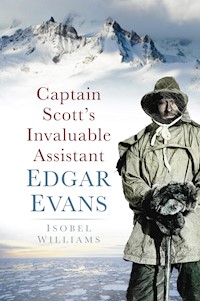

Petty Officer Edgar Evans was Captain's Scott's 'giant worker' and his 'invaluable assistant'. He went with Scott on both the British Antarctic Expeditions of the early 1900s – the 'Discovery' expedition of 1901 and the 'Terra Nova' expedition in 1910 – distinguishing himself on both. In 1903, with Scott, Edgar made the first long and arduous sortie onto the Plateau of Victoria Land. The journey highlighted Edgar's common sense, strength, courage, wit and unflappability. Thus it came as no surprise when, in 1911, Edgar was chosen by Scott to be one of the five men to go on the final attempt at the South Pole. Tragically the 'Welsh Giant' was the first to die on the ill-fated return, and posthumously Edgar was blamed in some quarters for causing the deaths of the whole party. It was suggested that his failure was due to his relative lack of education, which made him less able to endure the conditions than his well-educated companions. Isobel Williams repudiates this shameful suggestion and redresses the balance of attention paid to the upper and lower-deck members of Scott's famous expeditions.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to Gary Gregor whose knowledge about Edgar Evans and whose enthusiasm for the work has been a constant source of encouragement

Front cover photograph: Edgar Evans dressed for exploration. (Courtesy of Scott Polar Research Institute – SPRI)

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 The Gower Peninsula: Early Life

2 The Boy Sailor: Naval Training

3 The Discovery Expedition

4 From England to South Africa

5 The Southern Ocean to Antarctica

6 Early Months in Antarctica: February to September 1902

7 The Antarctic Spring: September to October 1902

8 The Antarctic Summer: October 1902 to January 1903

9 The End of the Discovery Expedition, 1903–04

10 Return from Antarctica, then Home Again, 1904–10

11 Terra Nova

12 The First Western Party

13 The Winter Months, 1911

14 The Polar Assault

15 The Aftermath

16 Why Did Edgar Die First?

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Dr David Wilson, the great-nephew of Dr Edward Wilson, Scott’s confidant and friend, has been a remarkable source of friendship, encouragement and advice throughout the work. My colleagues, Dr John Millard, Dr Howell Lloyd and Dr Aileen Adams, have diligently read the work and offered helpful comments, as has Mrs Jackie McDowell.

Professor Stuart Malin has patiently guided me through the intricacies of longitude and latitude. Lieutenant Commander Brian Witts, Curator of HMS Excellent Museum, Portsmouth, assisted me with details of the field gun run competition at Olympia. I am greatly indebted to these colleagues and friends. I accept responsibility for any misunderstandings or omissions.

The assistance of the staff at the Scott Polar Research Institute, The Naval Museum at Portsmouth and the Swansea Library has been greatly appreciated; all have been unfailingly courteous, helpful and enthusiastic.

Alison Stockton and James Oram, a Classics Undergraduate at Durham University, have patiently proofread the work and I am grateful for their help.

I have to thank Professor Julian Dowdeswell, Director of the Scott Polar Institute, for permission to publish extracts from those manuscripts over which the Institute has rights, also the Debenham, Shackleton, Skelton and Scott families for kind permission to quote from family papers. The Auckland Institute and Museum of New Zealand have allowed me to quote from Charles Ford’s journals as have the Dundee Art Galleries and Museums in relation to James Duncan’s papers. Mr John Evans, Edgar’s grandson, has allowed me to quote from Edgar’s sledging journal. Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders; any omissions or mistakes will be inserted into subsequent editions of this work.

Finally, my thanks must go to my husband, Dr David Williams, whose assistance and help made this work possible.

Introduction

Saturday 17 February 1912, Antarctica.

A man crawls helplessly on the icy snow, his clothes are torn open, his skis are off, his gloves and boots lie discarded on the snow, bandages trail from his frostbitten fingers.

He dimly sees four images coming towards him, but in his confusion he cannot work out what is happening. When his companions arrive he can hardly speak. He can barely stand and after a hopeless attempt at walking he falls back onto the snow. Three of his exhausted rescuers plod back wearily to the camp for a sledge.

They lay him on the sledge and struggle to pull him over the snowy waste. On the way he loses consciousness. He is never to be aware of his surroundings again. In the tent, as his companions watch, his breathing becomes irregular and shallow; he dies quietly at 10 p.m.1

So ended the life of Edgar Evans, the ‘Welsh Giant’ from Middleton in South Wales, a man who contributed hugely to Antarctic exploration, a Petty Officer who had built a relationship with his leader, Robert Falcon Scott, that transcended the barriers of class, rank and education. Theirs was a loyalty that had been built over long periods of interdependence as they endured the horrors of prolonged man-hauling at sub-zero temperatures in Antarctica.

Scott wrote that Edgar was a ‘giant worker with a truly remarkable head piece’,2 that Edgar was ‘hard and sound’ on a trek and had an ‘inexhaustible supply of anecdotes’.3 He chose Edgar as one of the five to go to the Pole.

Edgar died on the return, overcome by circumstances so awful that his four companions were soon to join him in icy tombs in Antarctica.

This is Edgar Evans’ story.

Notes

1 Ed. King, H.G.R., Edward Wilson Diary of the Terra Nova Expedition to the Antarctic 1910–1912, Blandford Press, London, 1972, p. 243.

2 Ed. Jones, M. Robert Falcon Scott Journals Scott’s Last Expedition, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005, p. 369.

3 Ibid., p. 303.

1

The Gower Peninsula: Early Life

Edgar Evans came from the Gower Peninsula in South Wales. Jutting into the Bristol Channel and open to the Atlantic gales, Gower is a place of outstanding natural beauty, a location that attracts visitors to its shores year after year. It boasts other famous attractions: in one of its coastal caves, the Paviland Cave, the oldest human skeleton in the British Isles was discovered – the ‘Red Lady of Paviland’1 (actually male remains) is tens of thousands of years old.

It would have been a remarkable astrologer who foretold fame for Edgar Evans when he was born on 7 March 1876 in Middleton Hall Cottage, Middleton – a village in Rhossili and one of the remote parishes on the peninsula. Edgar’s mother, Sarah, had moved to Middleton Cottage, her sister’s home, for her confinement.

This was a modest family. Their roots were firmly in Gower. Evans’ paternal grandfather, Thomas, and three previous generations of his family, came from the peninsula. Thomas was employed in a local limestone quarry (limestone was shipped across the Bristol Channel to fertilise the fields of north Devon). Thomas’ son, Charles (1839–1907), the father of Edgar Evans, was one of the famous ‘Cape Horners’, hardy seamen who sailed from Europe around Cape Horn to the west coast of America, a journey that could last six months.

The ‘Cape Horn’ trade grew because Swansea was then the world centre for smelting copper, essential in industry, construction and ship-building (the copper covering on ships’ hulls prevented the wood from rotting and made the vessels faster).

There were copper works in Swansea from as early as 1717. Approximately 2 tons of coal was necessary to smelt 1 ton of copper, and since South Wales was rich in coal, copper was brought to Swansea rather than coal being taken to the copper sources. When British ore was worked out, copper mines further afield were sought and Cuba and South American countries, particularly Chile, were used. These voyages to South America, in coal-carrying sailing ships, were hazardous undertakings. Life at sea was brutal and unforgiving. Off the Horn, with ‘winds at full-gale strength, waves as high as the maintops, sometimes hail and then snow coming down thick, clouds so low they enfold the mastheads, spume and sky indistinguishable’,2 forward progress was often impossible, some days the ship was set back by miles. Sometimes the voyage lasted four months, often much longer and many men died on the ‘widow-making’ passage. Added to the physical horrors of the crossing was the ever-lurking possibility of spontaneous combustion of the coal, likely to be disastrous in wooden ships and more probable if the coal was damp. After managing to survive the voyage, the sailors still had to contend with the perils of disease in South American ports. And then, having endured all that, the sailors faced the daunting prospect of the return journey. Years later, one of Edgar’s companions in the Antarctic wrote that only those who had had the experience could realise what it meant: handling frozen sails in the dark, short handed … and ‘so cold that the chocks (fittings for securing the ropes) have to be thawed with hot water before a rope will run through them’.3

But Charles Evans pursued this trade until he was in his mid-30s, well after the time he married and had children. In 1862, when he was 23, Charles, described as ‘Mariner, son of Thomas Evans, Quarryman’, married Sarah Beynon in St Mary’s church, in the village of Rhossili. Rhossili is one of the many villages dotted over Gower. It had 294 residents4 and was connected to its closest neighbour by just a muddy lane. Sarah was a local girl, the daughter of William Beynon, the licensee of the Ship Inn in Middleton, and his wife, Ann. She was 22 at the time of her marriage and her family had held the licence for the Ship Inn for most of the nineteenth century.

The ceremony was performed by the Reverend John Ponsonby Lucas BA, MA, an Oxford graduate, who ministered to several of the local villages. St Mary’s, with its beautiful Norman doorway, remains an active, functioning church. For many years a plaque in the aisle wall has proudly commemorated the life of Charles and Sarah’s famous son, Edgar.

As was usual in Victorian households, the couple produced a large family – there were eight known children. Birth control was unknown in working class communities in the late 1800s, and a high birth rate was a type of insurance policy against an unsupported old age. Four of the children are listed in the 1871 census: Charles, 7; John, 4 (both described as scholars); Mary-Ann, 2; and Annie Jane aged 1. The gap of three years between Charles and John suggests an infant death. In 1874, another son, Arthur, was born, followed, in 1876, by Edgar. A seventh child, George, was born in 1878 and a sister, Eliza Jane, in 1879. In fact Sarah Evans gave birth to more than the eight children; in 1913, after Edgar’s death, she was interviewed by a local reporter, and exhibiting stoicism difficult to imagine nowadays, she said that she had buried nine of her twelve children, three having died from consumption.5

Mrs Sarah Evans registered the birth of her fourth son in the sub-district of Gower Western on 13 April 1876. The 7 March was recorded as the birth date and Mrs Evans, unable to write (as was common, even six years after compulsory education was introduced),6 recorded her mark with a cross.

Interestingly, when Edgar entered the navy in April 1891, his Certificate of Service states that his date of birth was 9 March. Probably, once the error was officially recorded, the Boy, 2nd Class, then aged 15 years and 37 (or 39) days, thought it more prudent to go along with the official record than to challenge it, and he never corrected the date, although he is likely to have been aware of his registered birth date. Years later, in 1911, he wrote in his diary on 9 March, when he was on a sortie, that it was the ‘first time he has spent his birthday sledging’.7

Edgar was born into a small, tight-knit community. In the pre-First World War era, many people stayed within a few miles of their birthplace for the whole of their lives, and there was a huge interconnection of families through marriage. Sarah Evans had family links with many people in her village as well as brothers and sisters, some of whom were still living at the Ship Inn. So Edgar was born into a ready-made network of uncles, aunts, grandparents and cousins, as well as the immediate family crowded into his family’s cottage, which housed up to four of his older brothers and sisters as well as the babies, George and Eliza Jane. In addition, his father added to the crush on his intermittent visits home.

He learnt to speak in English as Welsh was hardly ever heard on that part of the peninsula. There must have been some incomers in Gower over the years because the villagers spoke in the ‘Gower Dialect’. This dialect, now virtually forgotten, had evolved through the influence of settlers from south-west England.

As a little lad he kept well out of the way of the local dignitaries; when the doctor visited on horseback or, occasionally, driving his horse and trap which carried the brightly coloured bottles of medicine that could be prescribed for virtually every ailment (since many of the residents could not read they were thought to be particularly impressed by the colours), Edgar took care to avoid him. Likewise, the Rector was an important local man. The Evans family were definitely ‘Church’ rather than ‘Chapel’ (the place of worship for the local Methodists). It is surprising nowadays to read of the chasm that existed between the two in some parts of the country (reminiscent of the Catholic/Protestant divide in Northern Ireland), but in Gower the division was only a pale and peaceful reflection of those clashes. When the Reverend John Ponsonby Lucas had married Edgar’s parents, he gave a girl a lift in his pony and trap, a journey of about an hour, but he was forbidden to speak to her because he was of the established Church whilst she was a Nonconformist.

By the 1881 census the family had moved to Pitton, the next small hamlet east of Rhossili. As was usual, only the people actually in the house on the day the census was recorded were counted, and Mrs Evans, ‘Mariners Wife’, registered her four younger children, now including Edgar, aged 5, as ‘scholar’ at the village school at Middleton. Forster’s Elementary Education Act of 1870 had stipulated that all children between the ages of 5 and 12 were obliged to attend school. The thrust behind this act was the fear that Britain’s status in the world could be threatened by the lack of an efficient national education system. It was a move by no means universally welcomed; there were fears that education would make members of the labouring classes, such as the Evans family, ‘think’ and so become dissatisfied with their lot. The Church also had doubts; its support for the biblical story of creation (which implies, amongst other things, that we are born to the station that we are meant to remain in) resulted in reservations. Also, the Church was already the recipient of state money for educating the poor and was reluctant to relinquish this. But once the Act was law, children were educated perforce. Edgar would be at Standard 1. He learnt his letters from an elementary reading book by copying a line of writing, in ‘good, round, upward writing’, and later wrote a few common words from dictation. He did simple addition and subtraction (of not more than four figures), as well as learning his multiplication tables (up to 6). Strict instruction was given on how to hold a pen – in the right hand with the thumb nearly underneath and three fingers flat out on the top; if his teacher saw him with one of his fingers bent he would have been rewarded by a rap on the knuckles.8 Edgar certainly benefited from the education he was given before he left school at the age of 12. His writing in later years was clear and his prose concise. The only thing that seems to have escaped his attention is punctuation; sentences flow effortlessly and sometimes confusingly, one into another.

In 1883, when his father Charles was 44, the family moved their home again. By now Charles had left long-haul shipping and was employed on a boat The Sunlight, which was involved in local coastal work based in Swansea, so the Evans family moved to the town. Swansea was important; it was part of the nation’s ‘workshop of the world’ and also known as ‘Copperopolis’ because of the prominence of the copper trade. The family moved to Hoskin’s Place, Swansea. They would have lived in one of the thousands of identical ‘two up, two down’ little terraced houses, with a communal back yard and ‘privy’. It is not clear just how many of the family made the move to Swansea; only the four youngest are recorded as being in the house on the 1881 census, but it is unlikely that Edgar’s 13-year-old sister Mary Anne or 11-year-old Annie would have left home by 1883, so it is probable that seven or eight Evans members (at least) shared the overcrowded facilities. Life was not easy. When coal could be afforded, the downstairs room was warmed by a coal fire, which was an integral part of an iron oven. Food was scarce: homemade bread and pies, meat once a week if possible, and potatoes. Water was heated by the stove and a tin bath (decorously concealed behind a clotheshorse decked with washing for privacy), was used for the weekly or fortnightly baths. Three or four members of the family used the same water.

With its population of over 50,000, busy streets, horse traffic, pollution from the copper works and noise, the town must have come as a shock to the country children; a huge contrast to sparsely populated Rhossili. Young Edgar was enrolled at St Helen’s School, Vincent Street, Swansea and remained there until he was 13. The school had just been enlarged when 7-year-old Edgar enrolled as a pupil and, with its 250 pupils, it too must have seemed huge. The life of the school and the education it offered is described by N.L. Thomas in a centenary booklet, A Hundred Years in School, St Helen’s 1874–1974,9 which shows how very fortunate Edgar and his fellow pupils were to fall under the influence of an enlightened, humane headmaster, Mr Lewis Schleswick. This was an opportunity certainly not enjoyed by all Victorian children. Mr Schleswick’s service was stretched; he had a small staff, certified assistants, uncertified assistants and pupil teachers10 and, to keep the teaching standards as high as possible, he taught the pupil teachers each morning before school began. The school remains. It is proud of its famous old boy and has Edgar’s picture prominently displayed.

As the school year progressed, Edgar, no doubt with the other pupils, was tempted by those infrequent but exciting diversions which lightened the drab routine of the Victorian school room, and often (as the daily school roll recorded) cut school attendance dramatically. Many of the children had to work for their parents before and after school. By a young age they were accustomed to a life of repetitive monotony and any glamorous excitement must have been a glorious break. Such delights were visits by circuses to the St Helen’s area, the occasional fair, regattas at Mumbles and Swansea, Saint Patrick’s Day11 celebrations (when school attendance was noticeably small) and, on occasion, processions. Once, after a Sunday school outing, over one hundred boys were absent. The reason given by the miscreants, according to Mr Schleswick, was that they were too tired to get to school.12 Occasionally, however, absences were official. When General William Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army, visited Swansea in 1883, the school was given a half-day holiday and when there was a large public procession in relation to the Blue Ribbon Movement,13 the boys were allowed time off to watch it. The headmaster wrote that not only the pupils but also the pupil teachers were given an official day’s holiday as a reward for their ‘unremitting zeal and energy’.14

Attendance could fall for more serious reasons. Mr Schleswick recorded that the summer of 1885 was exceptionally hot and it was difficult to keep the boys at their work as they were in a ‘state of exhaustion’. The area around St Helen’s was overcrowded, poor and susceptible to disease. Typhoid fever, that curse of unsanitary water supplies, attacked the school in 1896 ‘in spite of the drains being regularly disinfected by the Urban Sanitary Authority’. When Mr Schleswick inspected the drinking-water cistern, he found that it was filled with a deposit, to the depth of an inch and had a dirty filter.15 Other infectious diseases extracted a heavy toll: an outbreak of measles would close the school for three weeks,16 scarlet fever, that harbinger of rheumatic fever, sinus and ear infections, also visited regularly. Boys from houses where infection lurked were sent home to reduce the risk of cross contamination in this pre-antibiotic era, but death was a common caller. In 1887, there was a drought which had an impact both by causing dehydration and because the boys drank infected water. On this occasion wily local entrepreneurs profited by collecting barrels of water from springs in the countryside and transporting and selling the water to whichever urbanite could afford to buy it.

The end of the school day was the signal for those boys, who did not have to work for their parents, to escape to freedom. They made their own entertainment; since there were no cars or buses, but only slowly moving horse drawn vehicles, they could play on the street: trundling hoops, whipping tops or just standing in the middle of the street and gossiping. St Helen’s was close to Swansea Bay, famous for oysters, but probably of more interest to the boys as a glorious beach playground for football and swimming. Sundays were rest days. Edgar went with his family to Sunday school during the day and church in the evening. They all wore their ‘Sunday best’ clothes for the church visit.

Soon after his tenth birthday Edgar became a ‘half timer’. This exploitative use of cheap child labour meant that school time was cut, so that Edgar spent half the day at school, half at work. For his work he earned about a shilling (approximately £5 in current value) a week. He was relatively lucky. Fourteen years previously he could have been working as a ‘half timer’ from the age of 8.17 So Edgar’s total education was five years full-time (from 5 to 10), thereafter three years of half-time education. Nothing highlights the difference between the privileged and working classes of Victorian England better than their educational opportunities. By the time he was 10, Edgar, an intelligent child, would have been competent in the basic subjects: able to read, write to dictation and do arithmetic. Later he would have been introduced to a smattering of more interesting topics: geometry and geography.18 He would have been used to the idea of homework or ‘home lessons’. He would have sung – the Welsh are natural singers – and St Helen’s had a tradition for music and singing and the pupils were examined on their prowess.19 But his formal education was virtually at its end. By contrast, Dr Edward Wilson, who served with Edgar on both Scott’s expeditions as an officer and who came from a privileged background, was (although an average student) immersed in Latin, Greek, English, arithmetic and spelling by the age of 10.20 And Wilson’s education would continue for many more years. Education for the upper classes provided shibboleths to enter into a society that was virtually closed for people of Edgar’s education. His was the class that sailed the ships, worked the mines, smelted the ore and so underpinned for Britain those social and economic foundations that maintained her pre-eminence in the world. But the country was (in the main) proud of the Empire and proud to serve Queen and Country, and Edgar would have imbibed this pride.

From 1886, Edgar worked as a telegraph messenger boy in Swansea’s head post office. He carried his bag around Swansea delivering telegrams. His hours were long and tiring, and a fellow pupil from the 1880s recalls working till 10.30 at night.21 After Edgar’s death, his photograph, taken after his first Antarctic sortie, was displayed in the Swansea Head Post Office for many years. The photograph shows a good-looking young man. He was described as having blue eyes and a ‘fresh’ complexion.22 He was clean-shaven with brown hair, a straight nose, a strong jaw and a generous mouth.

The Head Post Master of 1886 decreed that messenger boys began their day with musket-duty and Edgar, between the ages of 10 to 13, was drilled and marched in procession, carrying his musket on his shoulders. A big event of 1887 was the visit of W.E. Gladstone23 (Victoria’s former Prime Minister) to Swansea to open a local Public Free Library. By now the boys were sufficiently drilled to march in procession to the library. How much they appreciated Gladstone’s speech on Irish Home Rule is not recorded.

Behind the post office was the North Dock. Here ships from exotic destinations would tie up and the boys were sometimes allowed on board. They would badger the sailors with questions, their imagination soaring along with stories of lands and adventures far, far beyond the confines of Swansea. Edgar had never been out of Gower. These visiting seamen and his father’s stories nurtured his determination to see the world, to become a sailor. In his early teenage years he decided that he would join the Navy as soon as they would have him.

However, he had to curb his impatience for a few years. In the meantime his mother took him to visit her family in Middleton. The journey was a step back in time for the newly sophisticated urbanite. To get there they had to travel by road to Pitton Cross and then brave the rigours of a high-banked, muddy, narrow lane, just wide enough for a horse and cart. But the Gower Coast had attractions other than family visits for a young boy. It was littered with wrecks: schooners, paddle ships, barques, oyster boats and ketches.24 Over fifty vessels – from a French vessel in 1557, to the Norwegian Barque Helvetia in 1887 – were known to have foundered in its treacherous waters. Edgar was 11 when the Helvetia ran aground in the southern part of the bay. He was enthralled at the story of her battle against the elements. On this occasion there were no fatalities, but her cargo of timber floated onto the beach and every available man, boy, horse and cart spent days loading the wood. Helvetia’s bare wooden ribs can be clearly seen today, sticking out of the sand in Rhossili Bay.

When he was 13, half-time work finished and Edgar left school for full-time employment in the Castle Hotel. Many of the captains of those copper ore barques berthed at North Dock actually frequented the hotel25 and their stories must have strengthened Edgar’s resolve to join the Navy. He read the Boys’ Own Paper (a relentless recruiting agent for the Navy), too.26 By now he was so keen to see the world that he actually tried to join up when he was 14. He was refused but returned to the Castle Hotel announcing, ‘I am coming back to you for another year and then I am going to join the Navy.’27

His parents were dismayed. Sarah Evans had known the hardship of bringing up (and probably already burying) her children with a husband away for months at a time. Charles Evans also tried to dissuade his son; he had had to have a leg amputated after it was damaged in an accident on his ship. But Edgar was determined. As soon as he could, at the age of 15, he applied to join the Navy.

The die was cast.

Notes

1 Investigated in 1823 by the Reverend William Buckland (1784–1856), Professor of Geology at Oxford, an eminent palaeontologist, who, because he was a Creationist and thought that no human remains could be older than the Biblical Great Flood, hugely underestimated the age of his find.

2 Lundy, D., The Way Of A Ship, Jonathan Cape, London, 2002, p. 15.

3Wild, J.R.F., Letter to Mrs Bostock. SPRI MS 1078/3/1; D.

4 Lee, S., The Population of Rhossili Gower, IV. Swansea, 1951, p. 27.

5South Wales Daily Post, Tuesday 18 February: ‘Consumption’ is tuberculosis, then endemic and causing death in over half its victims.

6 Forster’s Education Act. Drafted by William Forster, a Liberal Member of Parliament and introduced on 17 February 1870. The act provided elementary education for children aged 5–12. Parents were still expected to pay fees, though if they were poor, the board of each school would pay.

7Edgar Evans’ Journal, 27/1/11–12/3/11, SPRI: Ms 1487: BJ 9/3/11.

8 Thomas, N.L., A Hundred Years in School, St Helen’s, 1874–1974, Souvenir Centenary Booklet, held at Swansea Library, 1974, p. 22.

9 Thomas, N.L., A Hundred Years in School, St Helen’s 1874–1974, Souvenir Centenary Booklet, held at Swansea Library, 1974.

10 Pupil Teachers. Students who also taught.

11 The Patron Saint of Ireland.

12 Thomas, N.L., A Hundred Years in School, St Helens 1874–1974, Souvenir Centenary Booklet, held at Swansea Library, 1974, p. 2.

13 A Temperance Union.

14 Thomas, N.L., A Hundred Years in School, St Helen’s 1874–1974, Souvenir Centenary Booklet, held at Swansea Library, 1974, p. 15.

15 Ibid., p. 17.

16 Ibid., p. 15.

17 Factory Act of 1874.

18 Thomas, N.L., A Hundred Years in School, St Helen’s 1874–1974, Souvenir Centenary Booklet, 1974, held at Swansea Library, p. 22.

19 Ibid., p. 19.

20 Williams, I., With Scott in the Antarctic Edward Wilson, Explorer, Naturalist, Artist, The History Press, Gloucestershire, 2009, p. 25.

21 Thomas, N.L., A Hundred Years in School, St Helen’s 1874–1974, Souvenir Centenary Booklet, held at Swansea Library, 1974. p. 22.

22 The National Archives, Service Certificate (No.160225) Ref. ADM 188/235.

23 William Ewart Gladstone (1809–1898). Liberal politician and repeatedly Victoria’s Prime Minister. At the time of his visit to Swansea he was out of office, but was later to serve his final, fourth term.

24Gower, The Treacherous Coast. Map based on the original idea and research by Mike Downie. © Mike Downie, 1985.

25 A three-masted ship.

26 Winton, J., Hurrah For The Life Of A Sailor, Life on the lower deck of the Victorian Navy, Michael Joseph Limited, London, 1977, p. 288.

27 Gregor, G.C., Swansea’s Antarctic Explorer, Edgar Evans, 1876–1912. Swansea City Council, Swansea, 1995, p. 9.

2

The Boy Sailor: Naval Training

He did not have to wait long. The 5 April 1891, soon after his 15th birthday, saw Edgar attending his medical examination. Rules for medical fitness to enter the navy were laxer than today. A boy had to be without a physical deformity and to be able to speak clearly; he had to have good eyesight, colour vision and good hearing in both ears. There should be no obvious signs of injury to the head and he should not be of ‘weak intellect’.1 Boys who could read and write clearly were favoured.2

The navy wanted boys with ‘good heart and lungs’ and without any hernias or ‘tendency thereto’. There should be no disease or malformation of the genital organs.3

Of particular interest to Edgar were the regulations concerning teeth. These stipulated that boys below the age of 17 could have seven defective (decayed) teeth. Entrants over 17 could have ten problematic teeth, the only proviso being that all ages had to have four sound, opposing molars (two in each jaw) and the same number of incisors similarly placed.4 Dental hygiene was little practised in the 1890s and tooth decay was commonplace. Young people in the United Kingdom frequently had all their teeth removed as a 21st birthday present (an option clearly not open to would-be sailors), to avoid the infection, pain and expense of dental work. Edgar had eight decayed teeth.5 He presumably had to have these (or at least some of them) attended to before he was finally accepted after a special application.6

His career began on the training establishment for Royal Navy Boy Seamen, HMS Impregnable, on the 15 April 1891 for three days.7 After this Edgar Evans, Boy 2nd Class, official number 160225, was transferred to the wooden training ship HMS Ganges.8 Edgar’s Certificate of Service continued until 17 February 1912, when, as Chief Petty Officer, he was discharged, ‘lost in British Antarctic Expedition’.9 Roland Huntford denigrates Edgar Evans in his book Scott and Amundsen, by writing that over the years he turned into a ‘beery womaniser’, exposed to the risk of venereal disease.10 This might imply absences during his training, but Edgar’s naval Certificate of Service records no evidence of this, rather a seamless progress through the ranks.11 His ‘Character and Efficiency’ throughout this time is described as being ‘Very Good’, except for 1897 and 1899 when it was ‘Good’.12

Edgar started his new life at a time when Britain’s commercial and imperial power was at its zenith and the navy an important guardian of that power. But as there had been no major sea battle since the Battle of Trafalgar, Britain faced no obvious rivals and the service was perceived to be stagnating and becoming hidebound by tradition.13 It was also becoming a subject for national debate. The Naval Defence Act (1889) authorised the expenditure of £21,000,000 on the navy and the building of seventy-two new warships. The navy was to be on a scale ‘at least equal to the naval strength of any other two countries’.14

The navy was becoming fashionable, too. The Royal Naval Exhibition of 1891 was hugely popular; visited by over 2.5 million people, it aimed to draw attention to important aspects of naval life and history. Attractions in the exhibition included a life-size model of the lower deck of HMS Victory at Trafalgar (showing the death of Nelson), an area for field gun drill and manoeuvres, a lake with two miniature battleships fighting out naval engagements, a 167ft model of the Eddystone lighthouse,15 relics from Arctic expeditions and a fleet of fifty model silver ships.16 In 1893 the Navy Records Society was first published. This publication featured historical documents that illustrated the prestigious history of the Royal Navy and in 1894 the Navy League17 was established. This aimed to underline Britain’s status as a world peace power, to promote public awareness of the country’s dependence on the sea and to emphasize the fact that a powerful navy was necessary to maintain that power. The League stated that the primary aim of national policy was the command of the sea.18

Bluejackets (enlisted men with Edgar amongst them) were becoming the sentimentalised nation’s darlings and nautical dramas, such as Black Eyed Susan, True Blue and HMS Pinafore, became popular.19 Even Edgar, a 15-year-old ‘boy’, could share in this nationalistic pride. Indeed, in the popular imagination the British ‘tar’ was the envy of the world. Led properly, ‘he would go anywhere, do anything and do it with a will’.20 When Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee Naval Review took place in 1887, the Daily Telegraph wrote that the people loved their navy and believed in it.

The reality of training was very different from this imperialistic, jingoistic attitude. Many a fond hope for adventure and excitement must have been irredeemably crushed within hours of entering the service. Ganges, which Edgar joined in 1891 with his parents’ consent, was an old hulk in Falmouth, Cornwall, which served as a training establishment for Boy Cadets. Later, at 18, he signed for a further twelve years (in his case from 9 March 1894 to 9 March 1906) and then at the age of 30 he signed on for a further ten years. This second signing was essential because twenty-two years actual service (gaps due to illness or for other reasons were not counted) was the minimum required for a sailor to be eligible for a pension.21

Reading the accounts of life on the Ganges as recorded in extracts from the Falmouth Packet Newspaper 1866–1899, and reading personal accounts of the life endured by the Boys, is like looking through the two ends of a telescope. Both are undoubtedly true, but the training, aimed at toughening the boys, was harsh and often cruel. It must have often seemed overwhelming to the 15-year-old boy, now classified as Boy 2nd Class, and to the thousands of other Boys who went through the system.

There was no soft introduction. From the moment he was on board Edgar was caught up in the everyday routine. First he was told how and where to sling his hammock, then issued with his kit (for which he had an allowance: £6 in 1891, lesser amounts in 1893 and 1906).22 His civilian clothes were sold and he was introduced to the overcrowded, under-ventilated, unsanitary ship that was to be his base for the next year. The kit issued was quite extensive; over sixty items are listed in the Navy List for 1891, including jacket, jerseys, trousers, hats and caps, boots, bed and covers, a knife and two lanyards (ropes worn around the neck for securing whistles or knives). Intriguingly, two ‘cholera belts’ are listed; these are bands of flannel, sometimes with strips of copper in them, to be worn around the waist and thought to increase ‘bodily resistance’.23 It is not clear whether these were issued routinely against the possible perils of the training ships or held back for use in the east.

The Boys all had a ‘Housewife’ containing needles, buttons, thread and cotton, so that they could keep their kit in the condition demanded by the service.

In their day-to-day existence the Boys were entirely at the mercy of their Instructors. Lionel Yexley, a Boy on HMS Impregnable just a few years before Edgar joined HMS Ganges, recorded an existence that would have been similar to Edgar’s experience. The day began at 5.30 a.m. when, wakened by the shrill notes of the Bosun’s pipes and with his hammock safely slung and his kit in place, he was given a ship’s biscuit, plus a basin of hot cocoa with a little sugar. These biscuits were staple naval diet; they were routinely and famously full of weevils – little beetles, which swarmed out and floated in the cocoa when the biscuit was dunked in it. Breakfast came only after the Boys had worked for several hours scrubbing the decks. For this activity they had to pull their trousers above their knees and were not allowed to wear shoes or socks, even on the coldest days.24 Breakfast was a hulk of bread with a scraping of butter or dripping (on another ship, HMS Vincent, at about this time, no Boy was allowed his bread ration until he had collected two hundred cockroaches to exchange for the food). The meal was followed by sail drill and mast and yard drill, considered important in spite of the fact that there were few sail-driven war ships by the 1890s, although, as it happens, this training was to be of particular relevance to Edgar. He was instructed in all aspects of sail maintenance: shortening and setting, loosing and furling sails. Later he would learn about the rigging, climb the mast and gain knowledge of the hull.

After this came the prayers, read by the Captain or Chaplain, followed by gunnery training, with the Instructors concentrating on muzzle loading cannons similar to those used at Trafalgar.25 The Boys still had Cutlass drill.26

At 11.30 a.m. the instruction finished and the Boys fell in to witness the daily punishments. Flogging was abolished in Britain in 1891, partially due to the long-term efforts of a man with indirect connections to Edgar, Sir Clements Markham, ‘father’ of Scott’s first Antarctic expedition, but the cane, the birch and the rope’s-end (the stonnicky), were feared symbols of discipline. ‘Miscreants’ were whipped with a cane bound at both ends with waxed twine to prevent splitting. They were punished for offences that seem minor today: no chinstrap sewn on the cap, a button off the trousers or being ‘slack’ at falling in. For this ordeal, hammocks were lashed into a cross shape, the Boy to be caned had his shirt drawn up around his waist, leaving only his duck (heavy cotton) trousers to protect his buttocks from the vicious cane. Usually the punishment was six to nine cuts and the weals took about ten days to heal. Serious offences (theft or desertion) were punished by the birch, up to twenty-four strokes being permitted.27 This was an appalling punishment. In 1892 on the training ship HMS Boscawen in Portland, the birch was pickled in brine; this made it tougher, so that it caused more tearing and laceration of the skin (on this ship, the Corporals apparently took it in turns to administer alternate strokes, laughing as they did so).

After this terrifying experience, those with any appetite had their dinner. The Boys prepared this themselves and took it to the overworked galley cooks to be put in the oven. They ate meat and potatoes with occasional helpings of cabbage or doughboys.