18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

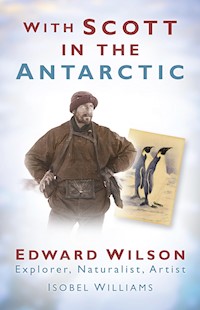

Edward Wilson (1872-1912) accompanied Robert Falcon Scott on both his celebrated Antarctic voyages: the Discovery Expedition of 1901-1904 and the Terra Nova Expedition of 1910-1913. Wilson served as Junior Surgeon and Zoologist on Discovery and, on this expedition, with Scott and Ernest Shackleton he set a new Furthest South on 30 December 1902. He was Chief of Scientific Staff on the Terra Nova Expedition and reached the South Pole with Scott, Lawrence Oates, Henry Robertson Bowers and Edgar Evans on 18 January 1912, arriving there four weeks after the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen. Wilson and his four companions died on the return journey. Trained as a physician, Wilson was also a skilled artist. His drawings and paintings lavishly illustrated both expeditions. He was the last major exploration artist; technological developments in the field of photography were soon to make cameras practical as a way of recording journeys into the unknown. This biography, the first full account of the Antarctic hero, traces his life from childhood to his tragic death.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

For D.J.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction by Dr Michael Stroud

Prologue

1 Early Years

2 Cambridge

3 Edward Wilson, M.B.

4 Antarctic Recruit

5 England to Madeira

6 To the Polar Ice

7 Entering Antarctica

8 Furthest South

9 Paintings and Penguins

10 The Grouse Challenge

11 Terra Nova

12 The Winter Journey

13 Death in the Antarctic

Epilogue

Notes on Sources

Selected Bibliography

Copyright

Antarctica

Acknowledgements

Whilst working on this book over the past five years I have discussed the subject with a number of people. All have been unfailingly helpful and enthusiastic and this has made the work a pleasure to undertake. Progress would not have been possible without the kind support of Dr David Wilson, Edward Wilson’s great nephew, who allowed me access to the Wilson Family Archive at Cheltenham and who has made helpful suggestions on the work throughout.

Staff at the Scott Polar Institute have offered efficient and ready help. I should like to mention particularly: Robert Headland, Shirley Sawtell and Mark Gilbert and more recent help from archivist Naomi Boneham, Lucy Martin, manager of the picture library and Heather Lane, the institute librarian.

Anne-Rachael Harwood and Stephen Blake in the Cheltenham Museum offered unfailingly cheerful and knowledgeable assistance. Several colleagues read sections, or indeed all of the work and I must thank particularly, Doctors: John Henderson, John Millard, Athena Leousi, Robert Bratman and Noelle Stallard. Mrs Jacqui McDowell and Nigel Oram have also commented.

Many colleagues have offered specific comments on detailed sections, in particular: Professor Sir John Crofton, Lady Eileen Crofton and Dr Max Caplin on tuberculosis; Professor Hugh Pennington on infection in the Antarctic; Professor C.A.C. Pickering on ‘allergy’ at low temperatures; Professor Stuart Malin on the mysteries of magnetism; Professor Jeffrey Wood, of the Food and Animal Science Department at Bristol, on vitamin C in animals; Professor Christopher Bates, Honorary Senior Scientist in Cambridge, on the difficult subject of bone and tissue breakdown in scurvy. I visited Dr Robert Thomas of Edinburgh Zoo on several occasions to view and talk about penguins. The late Dr Mark Harries discussed hypothermia. I am greatly indebted to these colleagues. I accept responsibility for any misunderstandings or omissions.

In the library at St George’s, Wilson’s and my medical school, Nalini Thevakarrunai gave every help possible, as did Anne Blessley, the curator of Bushey Museum; Sarah Strong, Archives Officer at the Royal Geographical Society; Pauline Widdows of Cheltenham College and her assistant Jill Barlow. Jaqueline Cox of the Archive Department of the University of Cambridge and Gemma Bently, the (then) archivist at Gonville and Caius, were patient with my repeated questions concerning medical education in the late 1800s. James Cox, the current archivist, added further information. Professor Sir Alan Fersht gave me invaluable information concerning Gonville and Caius College for which I am grateful.

Many thanks also to Dr Michael Stroud for his introduction to this book.

Introduction

I have always had an interest in Polar history, perhaps wishing to put my own Polar endeavours into context, but before I read this book, Wilson remained an enigma. Clearly, I had come across many descriptions of him amongst the diaries and works of his fellow explorers. Scott, Cherry-Garrard and others had all sung his praises and he seemed admired by everyone, yet his spirit and character had eluded me. Indeed, when reading entries in Wilson’s own Polar diaries, I had often found his descriptions of events almost curt and I had not really taken to the man. He seemed a strange puzzle. How could someone so clearly capable as a doctor, religious thinker, indeed real polymath, paint with such passion yet express himself so briefly, even coldly? I could not put these pieces together but Isobel Williams has let me do so.

This thoroughly and meticulously researched book brings Wilson to life. I now know that his many writings go way beyond Polar diaries and convey so very much more than I had realised. He had many strengths but he also had weaknesses, and this work provides a balanced portrayal. As such, it is in marked contrast to other modern accounts of the same expeditions which, although also carefully researched, have fallen foul of hopeless bias. Perhaps in an attempt to make the accounts more ‘newsworthy’, Roland Huntford for example lambasted Scott and all associated with him. He therefore failed to convey the wonderful qualities of these early explorers, essentially criticising them for acting like Edwardian Naval Officers, whichis exactly what most of them were. Huntford also criticised Wilson and others for pursuing the cause of science beyond the simplistic goal of racing Amundsen to the South Pole, missing the point that Wilson was a scientist through and through. Isobel Williams has not made the same mistake. Instead, she has caught the man in context, conveying the time in which he lived and the environment in which he worked. The result, describing his development from childhood collector, through budding artist and doctor, to a mature and superbly capable Polar explorer, is a book that rates beside the best on this heroic age of exploration. A book that captures the soft, thoughtful, considerate heart of Wilson the man, as well as the horrors of man-hauling, hunger and the hardship of the Polar blizzard.

Dr Michael Stroud

July, 2008

Prologue

In March 1912, in a tent on the bitter Antarctic wasteland, three men lay dying slowly, overcome by malnutrition, dehydration and hypothermia. Outside the tent a blizzard howled. The temperature was minus 40°F. The men had had little food for days, no fluid to slake their thirst. One of the three was Edward Adrian Wilson, the Doctor, Chief of Scientific Staff and ‘father-confessor’ of an expedition that had aimed to win the race to the South Pole for King and Country. The two other men were Robert Falcon Scott, the leader of the expedition and ‘Birdie’ Bowers, a man renowned for his stamina and strength. All three had succumbed gradually to the appalling conditions of their return journey from the Pole.

Sixteen men had started on the final expedition in November 1911. They knew that they would be competing with a Norwegian team led by Roald Amundsen and each man hoped and dreamed of being chosen for the final push to ‘bag the Pole’. Scott ultimately chose four companions: Wilson, Bowers, ‘Titus’ Oates and Edgar Evans from the group that had already endured nine weeks of energy-sapping travel. The five set off with high hopes, but when they eventually reached the Pole they found the Norwegian flag already there. There was nothing for it but to turn their backs ‘on the goal of their ambition’ and to face 800 miles of solid dragging to their base-camp on Ross Island. On this dreadful return two of the men, Oates and Edgar Evans, died earlier leaving Scott, Wilson and Bowers to battle on with their ill-fated effort to reach base-camp. The bodies of the three were found nearly eight months later, along with their personal and graphic accounts of the struggle to the Pole and their doomed attempted return. The terrible news of the death of the five explorers was blazoned around the world when the remaining expedition members eventually got back to New Zealand. In Britain hopes of welcoming the men back as the historic and courageous conquerors of the Pole gave way to a huge outpouring of grief. Over the weeks this sorrow was assuaged and partially replaced by pride in the men’s achievements as accounts of their heroism and endurance were published in the national and international press. The country became inspired. Throughout Great Britain and the Empire men, women and children were excited and encouraged by the story. Scott’s ‘Message to the Public’ that ‘Englishmen can endure hardships, help one another and meet death with as great a fortitude as ever in the past’1 caught the public imagination as an example of how to live and die when called to serve King and Country. The Daily Mirror, on 6 November 1913 wrote, ‘these last letters should be a battle cry to the youth and manhood of England. They should inspire and give heart and courage’.2 People of all ages soaked up details of the heroic adventurers and learnt what the human frame can make itself withstand. This made a lasting impression at an important time, just before the carnage of the First World War when the youth of the country was to be bombarded with sacrificial propaganda.

This book tells the story of Edward Adrian Wilson, a determined, self-contained, solid and deeply religious man who was the only officer to go with Scott on both his Antarctic expeditions of 1901 and 1910. After his death Wilson became a hero of Antarctic exploration, but he became an explorer by default. Whilst other Arctic and Antarctic travellers planned and dreamed of exploration and fame, Wilson’s interests as a young man were primarily directed towards natural sciences and painting. From childhood he had a passion for recording wildlife and he was precocious in his scientific objectivity; he would never accept theories without testing them. Though these attributes were to be of benefit to the expeditions, they were not developed for this purpose – he trained as a doctor and passed his medical examinations in 1900. By 1901 he had little medical experience and he was asked to go on the first Antarctic expedition, as Junior Surgeon and Zoologist, as much because of his artistic ability as his medical abilities; neither had he trained for exploration. In spite of these apparent disadvantages, his contributions towards the expeditions became legendary. His personality powerfully affected those in contact with him; he became a close friend and important influence on Captain Scott, who wrote of Wilson, ‘his kindness, loyalty, good temper and fine feelings have endeared him to us all. How truly grateful I am to have such a man with me and how much it lightens my responsibilities for the general well-being it would be difficult to express’.3 Others agreed, ‘if you knew him you could not like him: you simply had to love him’.4

Of his many interests exploration was only one. He was a naturalist, lifetime artist, doctor and researcher, involved family member and devoted husband. Above all throughout his life, even as a student, he was committed to a religious ideal and became by degrees a practical ascetic. His belief was that life is simply a journey towards eternity; this means that a successful life is judged by the effort put into it, not the outcome. Forgetfulness of self and actions to help others were his creed; he thought these more important than the bubble of worldly glory. He thought that life is measured by motives rather than by results, a belief that would have sustained and upheld him in the attempt at the Pole.

Some twenty years after his death, his wife Oriana collaborated with George Seaver to write his biography. The biography contains extracts of many of Wilson’s letters to her. Sadly she destroyed much of the remainder of this correspondence before she died, although many of Wilson’s letters to friends and his father’s memoirs remain. Seaver’s biography was obviously strongly influenced by Oriana and published many years after Wilson’s father (who had a very strong relationship with his son) had died. Now, nearly a hundred years after his death, it is time for a reappraisal of his life.

I first became interested in Wilson when, as a junior doctor at St George’s Hospital London, I sat in the common room surrounded by Wilson’s iconic paintings. St George’s was proud of their association with Wilson and Wilson enjoyed and appreciated his time there. He thought that the teaching was good and the range of clinical material excellent. He kept up his association with the hospital and after the first expedition returned on several occasions. Ill health meant that he did not practise as a conventional doctor in England but his medical training was an important part of his contributions in the Antarctic.

When Wilson first sailed to the Antarctic little was known about it and the interior remained a mystery. He would have known about the Arctic, which although dangerous and hazardous, had been opened up to a degree by successive naval expeditions, and explorations that were driven primarily by commercial and nationalistic impulses. The Northwest Passage (the sea connection north of Canada joining the Atlantic and the Pacific and thought to be a quicker passage to the Indies) was of strategic importance as a barrier to USA and Russian territorial claims and the Arctic seas yielded a valuable trade in whale-blubber for lighting and in seal fur. Scientific discoveries were a by-product of this trading, though many had potential commercial applications. By contrast the Antarctic was thought to offer few commercial opportunities and remained the world’s last vast unexplored space. Wilson would know that a Royal Naval expedition, under the command of Captain James Cook, had crossed the Antarctic Circle in the 1770s reaching 71° S, 300 miles inside the Circle. Cook described the seal colonies on the South Georgia Islands but gave up attempts to find ‘Terra Australis Incognita’ although he always suspected that there was a landmass in the south. More than fifty years later, another naval officer, Captain James Clark Ross, had been sent to the Antarctic to gather information about the location of the magnetic pole, the position of which was of importance for navigation. Ross’s expeditions reached the Antarctic and followed the mountainous coastline southwards until progress was halted by a wall of ice that he called the Great Ice Barrier. He was not able to explore the interior of the landmass. The seas surrounding the Antarctic, however, gradually became familiar to whaling captains who headed south to kill whales and seals, when demands exceeded supplies in the Arctic. An appetite for Antarctic exploration and scientific development was whetted when zoological and meteorological data started to reach Europe. The continued importance of Antarctic research, particularly in relation to magnetism, was understood and in 1901 expeditions left Germany, England and Sweden for the Antarctic. The English expedition (under Captain Scott and with Wilson as Junior Surgeon and Zoologist) spent two years in the south of Victoria Land. The thrust of the expeditions was scientific and included a magnetic survey of the area and a collection of botanical and geographical specimens as well as exploration towards the South Pole. This emphasis was to have a powerful influence on the second British expedition in 1910 whose mission was not only to reach the Pole but also to investigate meteorological, zoological and magnetic phenomena.

Wilson thought Scott a man worth working for: ‘I believe in him so firmly that I am often sorry when he lays himself open to misunderstanding. I am sure that you will come to know him and believe in him as I do.’5 He considered there was important work to do in the Antarctic. He was prepared to lose his life in the Antarctic as long as he had fulfilled his duties to the utmost. He was a tough, loyal and brave man who wholeheartedly took part in the expedition that led to his death but for which he recorded few regrets.

1

Early Years

Men of Edward Wilson’s family were explorers, entrepreneurs, businessmen, naturalists and soldiers; the family had a strong religious framework. For Victorians the family was both a refuge and the hub of their social life and Edward Adrian (Ted to his family) was part of a large and interconnected family. He was born on 23 July 1872, the fifth child and second son of Edward Thomas Wilson (1832–1918) and his wife Mary Agnes (1841–1930). His father was a doctor, a medical practitioner, in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire and Wilson was eventually to be followed by five younger siblings. He was born at a time when Great Britain was the hegemonic power of the world. Its citizens, in a way difficult to recognise in our multicultural age, were (in the main) proud that Englishmen were the undisputed rulers of millions. They did not question, and certainly felt no reason to apologise for, Britannia’s right to rule the waves, believing that God had ordained the Empire for the benefit of the world. Every schoolroom would have a map that showed that approximately 30 per cent of the world was coloured pink, the extent of ‘The Empire’. Children of the Empire, such as the Wilsons, born into middle-class households, were taught the importance of serving God, Queen and Country. They were proud to be British, and excited by the idea of serving the Empire.

Wilson was born in No.6 Montpellier Terrace. The house is still lived in, though the number changed. It is a good-sized house of four storeys and has sizeable rooms on the ground and first floor. When Wilson was born there was a nursery on the top floor, space for five live-in servants and a large kitchen in the basement. Nevertheless the household must have been fairly chaotic. Birth control was known but rarely practised and Wilson’s mother already had children of three, two, one and ‘under two months’ at the time of the 1871 census.1 The duty of married Victorian women, however educated, was to produce children and Mary Agnes did her bit. By the time of the next census in 1881 Mrs Wilson had eight children: thirteen, twelve, eleven, ten, eight (Wilson), five, two and a baby aged ‘less than two months’. Already one daughter had died.2

Wilson had had the conventional upbringing typical of thousands of children in England in the 1870s with one very important exception. At a time when children were often over disciplined, over controlled and physically punished, his parents were caring and supportive, intelligently committed to promoting their children’s health and happiness. They had the vision to allow their son unlimited freedom to explore the local countryside, to draw and to paint. Life was not boring. He had a happy childhood.

Cheltenham is an ancient town. It is recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086.3 Medicinal spring waters, which brought prosperity to the town, were discovered in the early 1700s. Visitors paid to take the waters (and visit the small assembly room nearby for billiards and cards), which were claimed as something of a ‘cure all’ particularly for digestive problems. They certainly acted as a laxative.4 The Wilson children would have thrilled to the names of the famous who had visited their town: Handel, Samuel Johnson and even King George III.5 They would have been proud that the Duke of Wellington, victor of Waterloo, had tried the cure, as had members of the exiled French Royal Family.6 These important visitors would have seen gentlemen’s clubs, tea dances, hunt balls, garden parties and concerts. They would not have seen the backdrop of poverty, the struggle for survival, the appalling living conditions endured by the poor of a town that, like many others, had a huge divide between rich and poor.7 But Dr. Wilson, the children’s father, would have seen it all. In his work as a general practitioner, he visited and helped patients in all walks of life.

Wilson’s parents had interesting ancestors. Dr Edward Thomas Wilson was descended from a family of rich Quaker industrialists. Wilson’s great grandfather (1772–1843), another Edward Wilson, of Philadelphia and Liverpool, was a hugely successful businessman who made fortunes from both American real estate and railway development and was a friend of George Stephenson who built ‘The Rocket’, the prototype for steam engines. The War of Independence resulted in Americans claiming much property owned by the English, so this Wilson was remarkable in that he successfully recovered his estates. He returned to England with his wife, Elizabeth Bellerby, and lived in Liverpool until his death. His children inherited fortunes and wrote ‘Gentleman’ as their occupation after their names.8 This was an important distinction that showed that they did not need to work for a living. His second son was Wilson’s grandfather who, in 1861, was appointed High Sheriff of Pembrokeshire by Queen Victoria.9 He was a keen and knowledgeable ornithologist; part of his collection became assimilated into the British Museum’s collection.10 Unfortunately, a series of poor investments meant that his children, although well-off, were not as privileged as their father and did have to earn their living. This they did to some effect. Wilson’s father, Edward Thomas, the eldest son, studied medicine at Oxford, St George’s Hospital London and Paris. He qualified in 1858 and was elected as a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of London in 1870.11 One of Edward Thomas’ brothers was the soldier and explorer Major General Sir Charles Wilson, who in 1865 conducted the first survey of Palestine and in 1884 commanded an expedition on the Nile in an unsuccessful attempt to relieve General Charles Gordon (Chinese Gordon), trapped in Khartoum by murderous Sudanese rebels. This expedition, when Wilson was eleven, brought Sir Charles national fame and must have thrilled the family. The Illustrated London News of March 1885 graphically fed readers’ appetite for military matters by a series of specially-commissioned illustrations of his expedition.12

Doctor Edward Thomas settled in Cheltenham instead of opting for a more lucrative and prestigious practice in London. He worked in Cheltenham General Hospital for over thirty years, initially in the dispensary and then as Physician to the hospital.13 He was a man of energy and courage and he was determined to help the poor and vulnerable in his hometown. The elegant neo-classical facades concealed many houses in a ‘filthy and unwholesome state’; overcrowded (several families in one room) and without drains. Outdoor earth closets or pail closets would have been shared by many people. Drinking water was often infected and illness very common, particularly in summer when the shallow wells that supplied many of the cottages dried up completely.14 Although busy with his large medical practice Dr Wilson gave time and energy to supporting public health measures to reduce disease. Such developments were often costly and therefore unpopular, but he persevered with innovations such as an Infectious Disease Hospital (to reduce person-to-person spread of infection), the training of district nurses and, most importantly, the provision of clean drinking water. He was a sophisticated and energetic man who passed on many of his interests to his son. He helped to found Cheltenham’s Municipal Museum, and opened it in 1907, saying that the museum might be made one of the town’s most valuable assets but in order to be this ‘it must not stand still’. He was president of the Natural Science Society and, aged 81, spent his summer in the Cotswolds searching for neolithic implements. He was a founding member, with friends, of the local camera club, the sixth oldest in the country.15

Wilson’s mother, Mary Agnes, too passed on to her son not only her deep religious beliefs, but also her enthusiasm for country matters and an artistic bent; one of her cousins was the Royal Academician, William Yeames,16 an uncle designed the Tsar’s garden. Mary Agnes’ family came originally from Cheshire, but her forebears settled as businessmen amongst the expatriate English community in St Petersburg, Russia. It was there that both of Wilson’s maternal grandparents lived and there that his mother was born. Her father, Bernhard Whishaw (1779–1868), ran a successful Anglo-Russian trading company. He married Elizabeth Yeames (1796–1879), also from a powerful expatriate English family, and the family was well enough thought of to enjoy the Tsar’s patronage. They spent their summers in their dachas and their winters in the city. In 1848 they moved to Cheltenham, probably for economic reasons, bringing their younger daughter Mary Agnes with them. Here she lived for the remainder of her life. Probably unusually for a Cheltenham girl of the time, she travelled extensively to the Continent before and after her marriage and was actually married in St Petersburg in April 1866. Many of her family who stayed in or returned to Russia, visited Cheltenham and the presence of these Russian visitors must have added glamour to the family and caused a frisson of excitement in the town.

This was a solid family, a family of ‘doers’ and enthusiasts, members of the ‘self-reliant and self-development’ line of thought. In Wilson’s case at least, grafted to these characteristics was an overwhelming conviction of the importance of faith. He and his mother shared a conviction in an all-powerful God at a time when the most entrenched precepts of the Church were being questioned. In the nineteenth century the concept of evolution shook and challenged the Church which taught that the universe was created in six days as described in Genesis. For years debates raged in the Geological Society and the Royal Society of London as new evidence challenged the Church’s teaching, which implied that everything, mouse to man and tree to mountain, was created at the same time. Darwin published Origin of Species in 1859 after years of hesitation and anxious study,17 tormented by the implications of his ideas which claimed that man was not created separately by an act of God but had evolved from lower forms of life over millions of years. Darwin wrote that different species including the human species evolved by random variation and adaptation to their natural environment, a development he called ‘natural selection’.18 For the supporters of the biblical story of creation, the Creationists, this theory had profound implications. Not only was it against the word of the Bible but acceptance of the theory could shake the social and moral foundations of society and even threaten Victorian England’s powerful class system, a system that mirrored the hierarchy of the natural world. It implied that men might have evolved from apes, that intelligence and morality were accidents of nature and that man and other new species arose from a series of random events and not from God’s will. Darwin feared that he was ‘the Devil’s chaplain’.19 Debates were fierce and passionate and have not been resolved to this day. Catholic academics still disagree as to whether or not random evolution is compatible with ‘God the Creator’. In 2005 President George Bush said that he thought the theory of ‘intelligent design’, a version of creationism that disputes the idea that natural selection alone can explain the complexity of life, should be taught in American schools alongside the theory of evolution.20 In the late 1800s, in a family as cultured, intelligent and interested in science as the Wilsons, arguments for and against would have undoubtedly been rehearsed but there is absolutely no suggestion that an appreciation that organisms can modify and adapt over time ever shook Wilson’s belief in an all-powerful God. He incorporated Darwin’s theories into his practical beliefs writing that God started life as a simple form, this form altered and developed into its designated role. God was present in everything: stones, trees, human beings and animals.21

Wilson’s understanding that minor changes in species can be effected in a few generations may have been helped in a simple way by his mother’s experiments with hens. Rather unusually for a Victorian housewife and mother, Mary Agnes was an authority on poultry breeding and published The ABC Poultry Book.22 This book covers a wide range of subjects in alphabetical order. Topics include: ‘Accidents, (including loss of birds by rail), Artificial incubation, Chilled eggs, Deformities, Rheumatism, Selling eggs and poultry’. Importantly, she grasped the concept that domestic animals could adapt to develop particular or new characteristics (for example, size or shape) by breeding with animals that already showed those characteristics; conversely, unwanted characteristics could be changed (although squirrel-tail deformity in hens is apparently difficult to breed out). Thus in a small way, in a Cheltenham chicken coop, she was able to demonstrate Darwin’s premise to her own and probably her son’s satisfaction.

Wilson’s mother had hoped for a second son, she already had three daughters. When he was born she wrote, with some partiality, that he was ‘the pride of the bunch’ and ‘the prettiest of her babies’. He had ‘deep golden red hair, eyes rather small, a pretty mouth and a lovely colour’.23 As a small child he was ‘bright and jolly, clever and quick’. He achieved his childhood milestones early, by the age of one he could run and climb stairs and was beginning to speak. He was, and remained, deeply attached to his father, ‘his love for him is most beautiful’.24 When he was 2, because of the increasing size of the family and perhaps because of his father’s growing reputation as a physician, the family moved to a larger house nearby: Westal on the Montpellier Parade. This was a large house of ten bedrooms, four reception rooms, a nursery, quarters for six house servants, a big garden and a private drive. The children had a (German) governess.25 This size of establishment would be fairly typical for a successful man of the period.26 The move was a success from little Ted’s point of view. He spent his time in the garden digging, trundling stones around and helping his mother. Westal was to be the family home for the remainder of Wilson’s life and he always remembered his years there with affection and happiness.

In his new home, Wilson’s artistic ability became obvious at a very early age. He was always drawing, and ‘never so happy as when lying full length on the floor and drawing figures of soldiers in every conceivable attitude’.27 His pictures were full of action and from his imagination; he did not like to copy anything. Soldiers were a favourite subject. They were probably foremost in his mind because of his Uncle Charles’ well-publicised explorations. Although his mother gave him drawing lessons, he was never to receive formal tuition. At three he was described as ‘a broth of a boy, a regular pickle, open about his faults but tearful and ready to cry on very slight provocation’.28 At 5 he was drawing incessantly; drawing and painting were to become a daily activity, an addictive necessity to him. Other interests and hobbies of importance in his later life also developed early, particularly a mania for collecting: shells, butterflies and dried flowers and probably many other things. Though ‘collecting’ was a very general Victorian passion, his collections must have been trying, as one of so many children, but his remarkable parents seem to have encouraged rather than discouraged him and given him a special room for his collections. Other characteristics were more worrying. His childhood temper could be described as cyclical; affectionate and sunny moods could quickly change to violent temper tantrums and screaming fits. His father stopped one of these episodes with a few good slaps which had ‘the most beneficial results, he became as good as gold and went to bed calling out, “Dood night, Dod bless you”’.29 These mood swings were much more marked than in the other children. Perhaps they were provoked by the death of his sister, Jessica Frances, who died in February 1876, aged 16 months when Ted, who was devoted to her and next to her in age, was 3. The cause is recorded as ‘Repeated attacks of convulsions’; these lasted for ten days.30 Childhood convulsions may be due to many things including infection and high temperature. In 1876, Cheltenham had an outbreak of Scarlet Fever (which can cause a high temperature and convulsions).31 The death certificate does not state the cause of Jessica’s convulsion, but it is easy to imagine the effect that the imposed silence, the muffled whispers, the parents’ dreadful anticipation and the final bitter outcome would have had on the household and on the psyche of a very young boy. Death was all too common in Victorian nurseries (infant mortality in Cheltenham from 1874 to 1884 was approximately ten times greater than adults)32 but although he understood that Jessie was going to Heaven, her death nevertheless must have been confusing, incomprehensible and frightening to a child like Ted.

His interest in natural history developed at an early age. At 4 he had a passion for flowers. When he was 9, he decided that he wished to become a naturalist and aged 11 he took lessons in taxidermy from White, ‘the bird stuffer’. His first attempt was a robin and he soon became nimble at this time-consuming and fiddly occupation. He always preferred country walks to games, and his collections of fossils, butterflies and feathers, and his aquarium, to lessons. His mother described him as ‘a nice looking, curly headed boy, very affectionate but decidedly slack at school work’.33 Early school was with his elder brother Bernard, and his teachers thought him clever, though his mother worried that he was ‘untidy, often idle, with returned lessons of which he was not ashamed’.34 It is easy to see why his attention strayed; the subjects taught were daunting, and by the age of 10 he was having lessons in Latin, arithmetic, English, reading, spelling and Greek. However, an ambition to do well was slowly asserting itself and he did work at school, so successfully that it was suggested that he might pass a public school scholarship (which would have helped his parents with the fees) if he was given extra tuition.35 As happens today, his parents paid for this extra tuition and he was sent to a boarding school in Clifton, Bristol in 1884. The school was small, about twelve pupils, and here he met an imaginative, enthusiastic and tolerant tutor, Erasmus Wilkinson, who created an environment that suited Wilson well – he was taken seriously and high standards were set. This proved the right method for a fairly turbulent boy and he responded well. He became so anxious to learn that he sat with ‘his back to his favourite beasties (the newts, frogs and mice which were allowed remarkably into the school room) which would distract him’.36 Equally importantly he began to lay foundations for his future development, learning to value accurate and careful records, and beginning to develop the habit of critical assessment. These were skills that were to become important in his medical work and in his expeditions to the Antarctic. During his time at Clifton he developed and matured. His rages and furies became rarer. Aged 12, he began to think about the meaning of life and ‘The Truth’; subjects that would absorb him and infiltrate his entire life. He started to try to relate his ideas for self-improvement into his day-to-day behaviour, wisely keeping these ideas and rules to himself. In his reports the schoolmasters commented only on his good sportsmanship and excellent manners. He tried for a public school scholarship at Charterhouse and Marlborough schools, but failed, having, his father writes, ‘been badly grounded in the classics’,37 but he valued the years spent at the preparatory school because he felt that he had been educated in the broadest sense of the word.

In 1885 his parents decided to rent a local farm, ‘The Crippetts’, near Cheltenham, where his mother continued to breed poultry and to practise ‘scientific farming’. The children kept pets, Mrs Wilson bred Dexter Cattle and the farm teamed with wildlife. Wilson fell for the farm as soon as he saw it, an ideal home for a naturalist and collector. He spent his summers cramming all the information he could about the foxes, badgers, birds and butterflies, which were there in numbers. Remarkably he was allowed to spend nights and days on the farm by himself, sleeping on the bare ground in an effort to toughen his body. He was, by this time, a committed naturalist. He recorded animal habits. He made notes on birdsong, cloud formation, indeed anything that appealed to the naturalist and artist. He began to try to observe, memorise and reproduce the varied, often brilliant colours of the Cheltenham countryside. This was another skill of tremendous use in Antarctica, where sketches started on a march, were completed in the base-camp. Eventually he seems to have developed almost perfect colour recall and never appears to have needed to use a colour grid to help his memory.

Further school education was at Cheltenham College where he started in the winter term of 1886. The school was, and remains, the local public school. There were family connections: Dr Wilson was the Senior Medical Officer and a founder of the college boat club; military Uncle Charles was also an old boy. Wilson went as a day boy in September 1886, going home at night unlike the majority of the students who were boarders. This pleased him greatly because he could escape after lessons to ‘The Crippetts’ and record bird habits rather than playing organised games (which he disliked all his life). Cheltenham College was founded in 1841 with the ‘aim of educating the sons of gentlemen on Church of England principles to prepare them for careers in professions or the army’. The man who shaped English public-school education, Dr Thomas Arnold of Rugby School, stated that his objective in education was ‘to introduce a religious principle’ and pupils were told that what was looked for was ‘first religious and moral principle, secondly, gentlemanly conduct, thirdly intellectual ability’.38 These concepts seem to have been followed in Cheltenham and were well suited to a serious pupil like Wilson. He was not outstandingly brilliant but managed to juggle work and hobbies satisfactorily. Predictably he became a member of the natural history and ornithology societies and his accurate and patient observation won him many prizes for drawing. He had the scientist’s love of knowledge for its own sake. For example, after starting to keep his own journal (having been inspired by Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle) he made notes on temperature, wind, birds, insects, zoology and ‘miscellaneous’, subjects of no obvious benefit to himself but recorded for his interest and learning. He also strengthened his ‘scientific reserve’, examining any precept thoroughly before coming to a conclusion; an independent review of the facts was essential. These naturalist and scientific enthusiasms are reflected in his school reports, which show that he had a talent in science, won prizes for drawing, had little aptitude for classics39 and had an average mathematical ability (‘works well but does not seem to grasp the subject’).40 In this he was given extra coaching and his difficulty with the subject was brought home to him later when he had to learn how to make observations in the Antarctic. Although to his teachers he seems to have been an intelligent but average schoolboy, he remained highly unusual by virtue of his religious convictions and inner ‘voice’ which remained strong. The Bishop of Gloucester confirmed him in March 1890.

He decided to follow his father into medicine. His schooling had prepared him for a professional career. Medicine attracted him because he had first-hand knowledge of the useful contributions his father had been able to make in Cheltenham. He would be aware also of the importance of his having a reliable income; he knew that his father still had six daughters and a young son at home. He had no bent to follow his elder brother Bernard and Uncle Charles into the army; his contemplative nature would have made him completely unsuited to the life. Medicine was a good choice. It offered a springboard for diverse opportunities: travel, specialisation in hospital, general practice, missionary work. In 1891 he took the Cambridge entry exams to study natural sciences and medicine. He did well and would have done better if he had not been ill at the time. He had hoped for a scholarship but he got a Certificate with Honours in science41 and was later awarded an Exhibition of £20 (with £3 for the purchase of books) at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge.42 To satisfy the General Medical Council of his suitability to register as a medical student he had to pass a seriously daunting number of subjects including languages, mathematics, logic and botany,43 but by now his intellectual ability had asserted itself. He had no difficulty with the examinations and like his father he managed to fit in innumerable interests in addition to his medical work.

2

Cambridge

Wilson entered Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge as an ‘Exhibitioner’, with his £20 a year grant, on 1 October 1891. He knew that Cambridge has been famous for its teaching for centuries. Alumni included: Isaac Newton, the mathematician who formulated the concept of gravity; William Harvey, who first discovered that blood circulates around the body; Charles Darwin, who shook the world with his theories of evolution; Lord Byron who shocked the world with his lifestyle and enthused it with his poetry and Thomas Lynch, one of the founding fathers of The United States. To a visitor Cambridge may impress with its grey stone buildings, grassy courts and chapels, but its reputation is firmly anchored to its huge intellectual and scientific contributions. When Wilson went to Cambridge the university had twenty-three Colleges. He arrived, holding the place in awe, but determined to play his full part in its life. His medical student registration certificate (number 20793) was signed on 9 October.1 He was to read for a degree in natural sciences and for his pre-clinical medical degree.

The last decade of the nineteenth century was described as the ‘golden era of the Cambridge medical school’.2 This description was coined because although medical education had vastly improved, a classical overtone was still very much in evidence as it had been at Wilson’s school. Students were still imbued with ideas of manliness and loyalty and the ability to govern was considered essential. The concept of ‘a Christian gentleman’ pertained and the undergraduates had to be familiar with Latin, the classics and to be able to write well. The students would know that a medical degree from Cambridge would automatically open doors to the most prestigious and respected positions in the medical profession, opportunities not necessarily offered to students from other universities. In Cambridge, Wilson would have known that he was one of ‘the chosen’.3 To start with the instruction was general; the lack of specific scientific teaching was not a concern, indeed, too early an emphasis on specialisation in the sciences was discouraged.4 However it would be inaccurate to think that medical studies were easier then than now. The requirements were certainly different, but they were daunting: medical students, to be registered by the General Medical Council, had to pass the Preliminary Examination with work done at school. Then they faced a long haul. Wilson went on to a series of further examinations with the aim of eventually achieving two degrees. The first was the natural science Tripos; this resulted in a Bachelor of Arts degree (B.A.) which, in spite of its name, was not in the arts, as most people understand them, but in chemistry, physics, mineralogy, comparative anatomy and much more. The second was the medical degree, Bachelor of Medicine (M.B.). Students did the first three years of the six-year medical course at Cambridge. Wilson faced regular examination hurdles. He passed Parts 1 and 2 of the first M.B. in the autumn of 1891.5 In 1893 he passed Part 1 of the second M.B. in pharmacy. He passed the final pathology examination in December 1893.6

The following year he took the first part of the natural science Tripos, for his B.A.7 Here he excelled and was awarded first class honours, having sat papers and done practical examinations in physiology, zoology and comparative anatomy, botany and human anatomy. He chose as his prize five volumes of the writings of John Ruskin, the art critic and social reformer, bound in blue calf, a valued treasure. This unenviable series of examinations were the norm for medical students, but by 1894, Wilson was very keen to get onto the clinical part of his course, which was to be done in London. His aim was to become a surgeon; he had had his fill of theoretical work and wanted to get down to the ‘real’ business. A painting shown at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1894 reflected his feelings. The picture showed a stylish-looking yacht surrounded by working steamboats and rowing boats. Wilson wrote to his father, ‘Butterflies and Bees’ is a picture in this year’s Academy and it just gives my ideas of the six years’ medical training. The first three are the butterflies up here, the three last are the bees in Hospital in Town and now the sooner I get there the better’.8 Unusually, the Master of the College asked him to stay on for an extra year. The reason for this was said to be that he could take the second part of the Tripos and that he was ‘a good influence’.9 Whatever the reason, Wilson’s parents, no doubt pleased that their son had been praised and singled out in this manner, persuaded him to stay on until 1895. He took two further examinations in this extra year: Part 2 of the second M.B. and the Part 2 of the Tripos. Although George Seaver says that Wilson failed both these examinations,10 he in fact passed Part 2 of the second M.B. in the Michaelmas term 1895,11 probably at a resit.

Although he had watched operations in Cambridge, by the time Wilson came face to face with a ‘real’ patient, he had already done four years of training and more loomed ahead. The final medical degree had to be taken after at least three years of clinical work in a teaching hospital. There was no clinical teaching in the Cambridge hospitals in the 1890s, so many students went to London for this training and returned to Cambridge to sit the final exam. Students had to pass exams in surgery, midwifery, general pathology, hygiene and medical jurisprudence. They had to produce certificates of ‘diligent attendance’ at the various courses.12 No one reading these requirements could suppose that medicine in the 1890s was an easy option or that the titles B.A. and M.B. were not well earned. When Wilson got to London in October 1895 he would have assumed that a further three years would finally free him of the examination yoke, at least for a time. The fates decreed otherwise. He was eventually to be a student for over eight years, finally being awarded the M.B. on 7 June 1900.13 In relation to all the examinations he sat however, there is no doubt that he followed the route dictated by the authorities.

Gonville and Caius is one of the smaller colleges in Cambridge. It was established in 1348 by Edmund Gonville and was refounded and extended in the sixteenth century by a doctor of medicine, John Keyes. It flourishes still. The College is called Caius because Dr Keyes, who had practised in Italy, ‘Latinised’ the spelling of his name. The College buildings include a chapel, a hall (where a flag bearing the Gonville and Caius Arms that Wilson took to the Pole still has pride of place), a library and accommodation, all built around grassy courts reflecting the founders’ aim of providing a communal place for study and prayer. Dr Keyes’ legacies to Caius of three carved stone gates named ‘Humility’, ‘Virtue’ and ‘Honour’ are important landmarks. Wilson was billeted high above ‘Virtue’, in rooms that were later dedicated to his memory, with a memorial plaque on the door. The gates were built in Renaissance style and are generally admired by visitors, though probably hardly noticed by Wilson and his friends as they dashed underneath them in their day-to-day student life. Wilson, like the other students, had a ‘gyp’ – a servant to look after him – and his, by chance, was a man who served with his Uncle Charles on the Nile Expedition, a coincidence that must have made him feel proud. Caius has several connections with Scott’s Antarctic explorations: the Canadian glaciologist Charles Wright who was on the second expedition, was an undergraduate at Gonville and Caius and the Australian geologist Frank Debenham was a Fellow of the College.

In Caius everyone would have known and been known by each other. Students studied a range of subjects, only a few were training for a medical degree. Disagreements and debates would have ranged and raged over the topics of the time: Darwin, art, literature, medicine. The students who joined in 1891 were said to be intelligent, also boisterous and rowdy.14 In this group Wilson was hardly domineering, in fact he was relatively quiet, but beneath this exterior he was confident in his views and certainly not overwhelmed by young men trying to impress each other. He was particularly unimpressed by the intellect of the students who had beaten him in the scholarship. Where he was unusual was that he was completely lacking in personal ambition in the sense of wanting to lead the group. Though in his early days at Cambridge he could still be aggressive, critical and argumentative and his temper could still break out alarmingly,15 he never wanted to dominate. His saving grace was that he had a sense of humour and was tolerant of other people’s opinions whether they coincided with his or not. He was easy to know, but difficult to know well. When he did give his confidence, however, he gave it completely and his companionship and considered thoughts on nature, religion, art and poetry were the reward; in discussions with his friends, he honed and tempered his thoughts on religion, life’s meaning and life in general. These friendships were kept in good repair throughout his life and later, when he was on the expeditions, he regretted that there was no one to whom he could open up as completely as he did in Cambridge.16 George Abercrombie, (1872–1961) was admitted to Caius on the same day as Wilson and trained with him also in London. Abercrombie went on to be a physician in the Orthopaedic Royal Hospital in Sheffield. John Roger Charles (1872–1962) was also in Wilson’s year. Another solid citizen, he became a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians in London and physician at the Royal Infirmary in Bristol. John Fraser (1873–1962) was also with Wilson throughout his student days. He went on to practise in Pietermartizburg and was the father of Wilson’s godson. Incidentally none of these friends were awarded first class honours in the natural science Tripos as Wilson was; Fraser and Abercrombie were given third class honours and Charles second class. Wilson was exceptional.17

Wilson’s weakness was his temper. He struggled to control it. Although probably uniquely for a medical student of his time his goal was to achieve perfect self-control, his resolutions were often blown away by an enraged outburst. But in his early twenties his temper gradually became calmer and he was obviously approachable and sympathetic because he became, unexpectedly, the mediator and peacemaker of his year; his peers obviously recognised his integrity and tolerance and could rely on his discretion. He would continue in this role for life. It was a responsibility he relished because it made him feel wanted and useful and that was enough for him. However he would never become a social animal, he lacked small talk. Concepts and ideas were his metier. In Caius he started to enjoy reading poetry, particularly Tennyson, who was to become a permanent love; he was reading Tennyson’s In Memoriam and Maud on his fatal journey from the Pole.18

Students mostly relish their independence and freedom when they leave home, only too keen to try new experiences. However there is absolutely no hint of any impropriety in relation to Wilson’s student days. Although as a ‘fresher’19 he took part in College activities actively and eagerly, there was another side to his character. Underpinning his surface enthusiasms he was a reflective young man, consumed with religious curiosity, unworried by personal or parental ambition and already thinking of himself as primarily answerable to his maker. By the 1890s, society was changing. Strict Victorian morality was soon to be lightened by Edwardian mores and many Cambridge students no doubt sampled the delights of the town. Wilson disapproved of any such activity, he was celibate; he tried to instil his ideals into his younger brother Jim, when he too went up to Cambridge a few years later. He advised Jim to have nothing to do with Cambridge town women:

Our family is a bit above that sort of thing, even in fun it is not a sign of superiority or manliness – rather a sign of true manliness is to have the greatest respect for even the most degraded woman. Don’t think there is anything you should learn about them practically because you will learn more than enough listening to your friends’ conversation. Remember you are a gentleman more truly than most of them you meet who may cut a finer figure and live up to it. Don’t ever underestimate your own power of example. You are responsible for the sins of others in so far as they are copying you – and you may save a soul alive and so cover a multitude of sins.20