Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

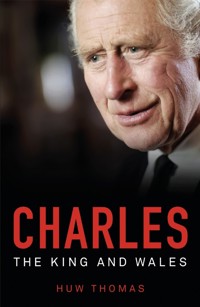

'It's a book which takes its time and really delves into the pivotal moments in Charles' connection with Wales... We are offered a glimpse at a man who has, over the decades, forged both a more formal support to Wales and a more personal warmth for it.' – Emma Schofield, Wales Arts Review 'This is a highly readable and lively book, full of anecdote and character... Thomas needs to be praised for producing a well-written and pacy book on a controversial subject which is neither hatchet job nor fawning tribute.' – Myfanwy Alexander, Nation.Cymru Before Charles became King, he was Prince of Wales. It was a role he took more seriously than any predecessor of the modern British monarchy. From the moment he was created Prince of Wales in 1958 until his accession to the throne, Charles's approach to the role was to serve Wales and to promote Welsh life. But what impact has he had on the country, and what impression did the Welsh leave on him? This book examines the relationship that the Prince nurtured with a nation that meant much more to him than an honorary title. Dozens of interviews have helped Huw Thomas to unearth the untold stories of Charles's work in Wales, alongside the key role he has taken in developing industry, culture and conservation. For a man who has spent almost a lifetime waiting to be King, Huw Thomas reveals how Wales prepared Charles for the crown. Despite his initial reluctance to come to Wales as a student, his time spent learning the history and language of the Welsh at Aberystwyth in the 1960s fostered a passionate commitment to the nation. Wales has not always returned the compliment, with popular protests and more subtle snubs to his involvement in Welsh affairs. And yet those who have worked with him, and who call him a friend, cite a remarkable ability to make a difference without making a fuss. As a diplomat he is credited with bringing major employers to south Wales, offering jobs to a workforce that had been decimated by the collapse of the coal industry. As a cultural ambassador he revived royal patronage for the arts in Wales and sponsored the finest performers to emerge from the land of song. And as a champion of the natural environment, he has backed the farmers and conservationists who are nurturing the Welsh countryside, not least by employing traditional crafts to create the first royal home in Wales for 400 years.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 429

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

About Huw Thomas

Title Page

Dedication

The Prince's Youth Business Trust

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. Creating a Prince of Wales

2. Sending the Prince to Wales

3. The Investiture

4. Doing Business

5. ‘World Class’

6. Private Passions

7. A Home in Wales

8. Playing Politics

9. Bridging Two Nations

10. To be a King

11. William of Wales

Modern Wales 1

Modern Wales 2

Modern Wales 3

Modern Wales 4

Parthian: A Carnival of Voices

Copyright

Huw Thomas is a journalist whose writing and broadcasting covers the beating heart of Welsh life. Born in Maesteg in the post-industrial south Wales valleys, for the best part of twenty years he has reported on the people and places of Wales. He began in local radio, before joining the BBC after a brief stint producing business news for Bloomberg. His work has taken him around Wales and the UK, covering key events from the Queen’s Jubilee to the Olympic Games, and the Hay Festival to the National Eisteddfod. Stories have also lured him abroad, allowing him to interview the descendants of Welsh settlers in Patagonia and Bonnie Tyler at the Eurovision Song Contest in Sweden. Huw is an accomplished TV correspondent, having covered the darkest days of the Covid-19 pandemic, while his presenting skills have seen him front programmes for BBC Wales and network radio.

Charles

The King And Wales

Huw Thomas

For Isobel, Clara and Alys

Parthian started publishing books with a loan from the Prince’s Youth Business Trust in 1993. We would like to thank the Trust and particularly Dr Martin Price, for his expertise and engagement in our development through the Trust's excellent programme of support for young people starting a business.

Acknowledgements

When I first began researching this book, the nature of the polarised responses I received made me question whether it was possible to adequately assess the impact that Charles made on Wales, and to what extent the Welsh had rubbed off on him. Fortunately, dozens of people were prepared to share their own stories of Charles’s sixty-four years as Prince of Wales. The resulting interviews, conducted in office blocks and stately homes, created a picture of Charles’s Welsh interests and how Wales influenced the man who would be King.

I am indebted to those who gave their time, often on more than one occasion, to discuss their own encounters with Charles. Many of them are named in the chapters that follow. My heartfelt thanks is also extended to those who cannot be identified but whose valuable insight helped to shape the narrative of this book. Others who supported me by checking facts, reading extracts and discussing concepts have also contributed to my story about the King’s relationship with Wales. The support of my family in pursuing this book, from Covid lockdown to the eve of the King’s coronation, has been an incredible blessing. Having said all of that, any errors or omissions are entirely my own.

Introduction

‘For me it is a way of officially dedicating one’s life, or part of one’s life, to Wales. And the Welsh people, after all, wanted it.’

It is a spring morning in 1969 when a blue sports car glides to a stop outside a Welsh country house. From the driver’s side a man emerges quickly and fumbles briefly with his light brown suit. A buttoned-up blue shirt and his tie, taut and restrictive, remain unruffled by the short journey. The man is self-conscious, his hands quickly slide into the unstitched pockets of his suit jacket. While the sixties swung, this man remained rigid. He glances at the newsreel camera which whirs its colour film. The glance never fixes on the barrel of the camera lens, instead the eyes scatter until he has turned around on the spot. He takes a small, awkward pirouette towards the back of the car to exchange inaudible small talk with his companion before he returns to the safe space between car door and front door; that sweet spot where the camera can sustain a few more seconds on the face of the man who will be King, but only for as long as he can bear to be on show.

Charles had almost finished a pre-investiture public relations epic when this scene played out on the drive of the manor house on the Faenol estate near Bangor, north-west Wales. His MG sports car, new in 1968, was the ostentatious shell for a shy public schoolboy whose path in life was indelibly etched at the moment of his birth. His friends, at school and at Cambridge, may have shared the great privileges of the aristocracy. But while their gilded paths opened doors to investment banks and the Inns of Court, Charles would take an almost lifelong walk along a deep-pile red carpet. Its destination was the crown of the United Kingdom. It is perhaps unsurprising that when life sets such a singularly simplistic and elusive goal the bearer is forced to define their existence by other achievements. The freedoms offered by great wealth and class are curtailed for royalty by the duties and service that is expected of them. For the heir to the throne, such expectations are closely defined and restrict the liberties that their siblings, cousins and aunts could indulge. But for an heir in need of an agenda, a self-defining role can be created to fill the time between reaching adulthood and reaching the throne.

The Prince’s coming-of-age coincided with an awakening in society that swept aside the stuffiness of post-war Britain and celebrated the free-thinking and free-loving that was fostered by the 1960s. Two decades earlier it had seemed radically modern that the Home Secretary had not been present to witness Charles’s birth. James Chunter Ede was the first Home Secretary in over a hundred years to have been absent from the arrival into the world of a senior royal, a practice rooted in the fears of Tudor and Stuart monarchs that their line of succession would be stolen by a changeling or a chancer. Despite the dawning modernity, Charles had been born into an ancient system of monarchy and was expected to keep it going. His supporters, while championing the ambitions of a modern prince, also pressed his pedigree. He was fifth in descent from Queen Victoria and could claim a direct route back to all the kings and queens whose names had graced schoolbooks, postboxes and pub signs for centuries. There were connections made, too, with Charlemagne, Vortigern and Cadwallader, although genealogy means most Europeans alive today could probably claim a similar pedigree. Journalists published complex family trees that linked the future Prince of Wales with the ancient and original title-holders. It was possible to claim that Charles was twenty-fourth in descent from Llywelyn the Great, a king of Gwynedd and one of the last native Princes of Wales before the title’s thirteenth-century conquest by Edward I. The public relations effort was designed to embed the idea that this was a boy prince whose lineage did not deviate from the warrior men who had gone before him.

While history charted the bloody battles for Welsh territory and Welsh titles by neighbouring rulers, the happy birth of a modern heir focused attention on celebrating tenuous genealogical links, overlooking the murderous conquests that had shaped the family tree. The grandson of Llywelyn the Great suffered a beheading which not only cut off the Welsh claim to the title Prince of Wales, it also created a totem in the story of Wales that bolstered sentiment for independence from the English, and fomented in some an ongoing rejection of the title when worn by any heir to the throne since Edward II.

If Charles had a hereditary connection to the last native Welsh princes, it was a connection that was lost on Welsh historians. ‘With the fall of Llywelyn ap Gruffydd an epoch ended – the Wales of the Princes,’ wrote Gwyn Alf Williams in When Was Wales? ‘The Welsh passed under the nakedly colonial rule of an even more arrogant, and self-consciously alien, imperialism. Many historians… have largely accepted the verdict of nineteenth-century Welsh nationalism and identified the house of Aberffraw as the lost and legitimate dynasty of Wales. Llywelyn ap Gruffydd has become Llywelyn the Last,’ wrote Williams. Whatever the bloodlines drawn to impress Charles’s pedigree, the blood ran clear for some.

And yet the line of succession had never landed during a time of such huge societal change and liberation from the chains of tradition. The relaxing attitudes of the 1960s presented an opportunity for Charles to write his own job description. In 1968 the journalist Dermot Morrah charted the early years of the Prince, having evolved from being a correspondent for The Times to occasionally writing the Queen’s speeches. His authorised biography of Charles’s young life described the upbringing of the Prince and, assuming a long reign for his mother, offered a thesis on the heir’s adulthood:

Prince Charles will require to find some new direction of princely activity for the common good, something that grows out of the needs of the modern world as it is, and as it is becoming. He belongs to that world, and, at the end of the thoughtful years on which he is about to embark, will be better able than his elders to judge how best it can be helped.

The prospect of determining his own ‘princely activity’ must have seemed both daunting and delightful. He had an enviable opportunity to map out a role that allowed his preferred pursuits of culture and countryside to be the anchor points of a period as heir which, even then, seemed to offer a good thirty years before having to worry about becoming King.

As a modern Prince of Wales he could heal the scars left on the House of Windsor by the previous bearer of the title, Edward VIII, who took the throne and handed it back in pursuit of that most uncommon royal commodity: love.

Charles’s shoulders would carry the investiture robes a little more sensibly than another Edward, the seventh to bear the regal name when he eventually grasped the crown. Before taking the throne in 1901 Edward VII had spent the best part of sixty years gallivanting the globe as the playboy Prince of Wales. Aged thirteen he had attended a party thrown by Napoleon III in Paris which exposed the young prince to the vices available beyond Victorian England. While his mother’s name became a synonym for stuffy conservatism, the young Prince rebelled against his restrictive childhood. He is said to have lost his virginity aged nineteen on a ten-week tour of Ireland with the Grenadier Guards and continued to travel widely in order to indulge his passion for women and gambling. His mother’s longevity ensured he could spend decades exploring the attractions of the expanding Empire.

Examples from recent history may have been enough to chasten any of Charles’s more radical ideas for his time as Prince of Wales. In fiction, too, there were near-the-bone notes of caution. ‘To be Prince of Wales is not a position – it is a predicament!’ said Alan Bennett’s heir to the throne in The Madness of King George.

In 1969 it was Charles’s chance to either make it work or mess it up. He would proceed in plain sight of those who wished him to fail, and knew not only that there were a minority of committed anti-monarchists who were determined to protest his path to the title of Prince of Wales, but also that there existed a largely indifferent majority who may tune in as much for the spectacle of the investiture as they would for his wife’s Panorama interview twenty-five years later.

Sympathy for a prince can be a struggle as much in the 2020s as it was in the 1960s. When Charles’s youngest son told the American television presenter Oprah Winfrey in 2021 that he had felt ‘trapped’ in the clutch of the royal family, she responded to Prince Harry with a jaw-dropping call for clarity. ‘Please explain how you, Prince Harry, raised in a palace, in a life of privilege, literally a prince, how you were trapped.’ Similarly, ahead of Charles’s investiture, there were crocodile tears from the era’s cultural critics. The republican Labour MP Emrys Hughes hid many truths in his sarcastic take on Charles’s ceremony at Caernarfon Castle. ‘If a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to the Prince of Wales is formed, I will immediately send a subscription,’ he told the House of Commons in a debate about the investiture in December 1968. The record of proceedings continued: ‘There is no need to drag the unfortunate Prince of Wales through what his predecessor had to undergo. Having seen the photographs in the Manchester Guardian I am more convinced than ever. The then Prince of Wales [later Edward VIII] had to appear in a uniform with swaddling-clothes. In one hand he held a wand, in the other a sword, and he had on something that looked a cross between a duffle coat and a mini skirt. It is sheer cruelty to have the Prince of Wales taken to Caernarfon and televised before four hundred million people. I ask the Minister to support me in preventing it.’

It was not prevented, of course. When his MG car arrived on the tarmac of the Welsh country house that morning in a final publicity push, Charles entered a room with a waiting camera and lights rigged by British Pathé. He would provide a soundbite that would play out on newsreels in picture houses around the world as they showed the highlights of his investiture:

I feel that it is a very impressive ceremony. I know that perhaps some people would think it is rather anachronistic and out of place in this world, which is perhaps somewhat cynical. But I think it can mean quite a lot if one goes about it in the right way. I think it can have some form of symbolism. For me it is a way of officially dedicating one’s life, or part of one’s life to Wales. The Welsh people, after all, wanted it.

1

Creating a Prince of Wales

For thousands of years the birth of a son, and sometimes a daughter, to the chief of a tribe was greeted with celebration and relief. The existence of an heir confirmed the longevity of the line. A strong leader was nothing without a successor, and for millennia the figureheads of countries and continents have corralled their populations around their own superior status to fight wars and to populate new lands. They had the power to persuade and press their followers to fight and die on their behalf in battles from Bosworth Field to Massachusetts and Mumbai. They could command taxes and treasure from their subjects as much as from their conquered territories, and the many wars and land-grabs would often enrich the leader’s coffers as much as it would expand their empires. Each ruler had his trusted advisors, from the tribal elders to the royal court, but there were few accessories more valuable to a king’s grip on power than the arrival of an heir. For over seven hundred years the Prince of Wales has been heir to the crown – first of England, and then of Britain. But just as monarchy has survived the redrawing of boundaries and the development of democracy, the title of Prince of Wales has endured in spite of the tension of its creation and the indiscretions of some of the men who held it.

And they have always been men. Kind men, mean men, lecherous men, clever men. Men who were empathetic and flawed, men who were clever and conniving. The short-lived, short-tempered and short-trousered. Those who made the title of Prince of Wales a laughing-stock, and those who made the job last a lifetime. Since 1301 the Prince of Wales has been a title and little else – it comes with no land with which to recoup rents, income or taxes. While the Welsh nation is notionally attached, no Prince of Wales has been Welsh since the thirteenth century and no product or place in the country is indelibly tied up with the title. When William was created Prince of Wales in 2022 it was in the gift of his father, the King, to pass it to his eldest son. The more lucrative decoration for the first in line to the throne is the Duchy of Cornwall, a profitable portfolio of assets that immediately passed into the possession of William at the moment of his grandmother’s death. The title of Prince of Wales does not come with a prescribed or specific routine, nor an official regalia. Recent centuries have seen the adoption of the three ostrich feathers as an official crest, but items such as the crown worn by Charles at his investiture were a 1960s creation likened more to a sparkling kitchen colander than a symbol of the ancient English throne. Under the British monarchy the Prince of Wales has been a badge worn by the male heir, and a title with which the bearer can do as they please. The very absence of any onerous duties belies the great political significance of its creation under the English Crown, its symbolism a potent and still sometimes toxic reminder of the conquering armies that rampaged across western Britain in the thirteenth century.

The original Welsh Princes of Wales weren’t heirs or spares, but the leaders of their kingdoms. The Welsh word for prince, tywysog, came to mean a male leader. But it is a word which defines itself as more than the chief of a tribe. Should somebody express in Welsh that they wish to tywys you, then their role is that of a guide. They are an experienced companion who can steer you through unfamiliar territory, from darkness into light. They are not second-in-command or a king-in-waiting. In the history of Welsh princes, they were men whose territory was hard-won and fiercely defended, but who were noted, too, for their compassion and desire to improve the lives of their people. Many layers of mythology have been applied to the Welsh Princes of the Middle Ages. The likes of Hywel Dda, Llywelyn ap Gruffydd and Owain Glyndwˆr have legacies which are swathed in historical treacle. The goal of creating political unity in Wales and leading resistance to invading armies, is often the sum total of modern Welsh understanding of the princes that ruled around a thousand years ago. It was a Wales that placed itself firmly among the nations of Europe, and which had embraced Christianity and the role of religion in public life.

The Wales that was ruled by Welsh princes had barely a town on the map. Its territory was farmed by labourers and slaves, with the warring princes ruling a number of different kingdoms within the modern map of Wales. The Welsh saw themselves as the natural leaders of Britain, a position earned by being descendants of the Celtic tribes who had settled broadly across the isles of what would become the United Kingdom centuries later. But while the Welsh may have laid claim to much of the island of Britain, the occupiers of modern-day England saw a population now enclosed on its western edge and which was different to the rest of them. Their Celtic genetics gave them a more fierce appearance, while their tongues spoke a Welsh language that bore little relation to the Anglo-Saxon English that developed next door. The Welsh princes, far from edging towards broader domination of Britain, would face a fight to stop their territory being gobbled by an all-consuming England.

This book is not an historical account of all of the princes, but it is important to note the title-holders who came before Charles. The treachery and gruesome torture of the Middle Ages has left scars that run deep in the psyche of many who oppose monarchy, support Welsh independence, or both. The name of Llywelyn ap Gruffydd is incanted by those who despise Charles’s embodiment of the role of Prince of Wales and will be as hostile to William in his attempts to carve out his own distinctive path. But even those with milder antipathy and who oppose the title without any personal vindictiveness against the most recent incumbents will invoke the name of Llywelyn ap Gruffydd as the never-to-be-forgotten and final true Prince of Wales.

Llywelyn ap Gruffydd

Prince of Wales 1258–1282

Llywelyn’s claim to be Prince of Wales in the thirteenth century was confirmed not just by the extent of the territory he managed to rule – around three quarters of Wales – but by the acknowledgement of the English monarch at the time, Henry III, that Llywelyn deserved the title. Nobody before had ever been called Prince of Wales by a King of England. The official recognition of Llywelyn’s status came when both men agreed to the Treaty of Montgomery, signed on 29 September 1267 near the town which sits on the border between the two nations. The treaty required Llywelyn to give homage to the King, but it also gave land and power to the Welsh prince following years of fighting. Such was the significance of the Treaty of Montgomery that it was brokered, in part, by the Pope’s representative in Britain and signed by Llywelyn and Henry near the bank of the River Severn at Rhydwhyman.

Generations of princes of the different parts of Wales had fought over land, but only Llywelyn had succeeded in reaching a political deal that would allow him to use the title. The price of the agreement was high, with Llywelyn required to pay the Crown an annual levy which was equivalent to millions of pounds in today’s money. The bill was several times higher than Llywelyn’s existing annual income from the land he controlled, and in order to pay for the treaty the Welsh people would be required to contribute more to the coffers. Llywelyn’s rule was oppressive according to some of the people, predominately those in the north-west territory of Gwynedd, who had to pay the price. Gwynedd was Llywelyn’s home, but it was also the most productive of the Welsh land under his control. He appointed tax collectors to recoup the revenue required to satisfy the King, proving that Llywelyn was prepared to pay an eye-watering amount to the English Crown for the right to keep calling himself the Prince of Wales. It also made him Prince of the Princes, a unifying figure for the Welsh following decades of bloody conflict among local leaders and between English and Welsh armies.

The relative tranquillity of those early years of Llywelyn’s rule as Prince of Wales came after a brutal campaign that spanned two decades. He had fought with Henry III’s armies for most of that time. Llywelyn’s grip on power had also pitched him against his brothers; family ties had become obstacles to political dominance. Llywelyn banished his siblings and created alliances with Welsh noblemen to advance his dream of a unified Welsh principality, while Henry had faced his own local revolt. English landowners, led by Henry’s brother-in-law Simon de Montford, fought against the King. It was a war that briefly suspended the monarch’s grip on some English territory and posed a direct threat to his reign. Nobilities of the Middle Ages seemed to intertwine as much, if not more, than their modern equivalents. Llywelyn backed de Montford and would later marry his daughter Eleanor. When de Montford was eventually cornered and killed in 1265, the King’s troubles in England subsided. Reaching rapprochement with the de facto leader of the Welsh was part of the broader settling of arguments, and two years later Henry and Llywelyn met to sign the Treaty of Montgomery near the banks of the River Severn. While Llywelyn had achieved his ambition, within a decade his principality would be decimated by further battles and a changing monarch. The Treaty of Montgomery had given Llywelyn the right to be called Prince of Wales, but the use of the title by the Welsh leader relied on the continuing approval of the King of England.

In 1272 Henry III died at the Palace of Westminster, his reign of fifty-six years ending with his burial in the grave of Edward the Confessor at Westminster Abbey and his heart removed and despatched to a holy spot at Fontevrault in Anjou, France. His son, Edward I, would construct an ornate tomb at Westminster Abbey to honour his father’s legacy. But Edward would also push back against the alliance made in Wales to an ultimately devastating effect.

The relationship between Edward I and Llywelyn was fragile from the beginning. Llywelyn, who had to pay homage to the new monarch as part of the agreement to keep the title of Prince of Wales, did not attend Edward’s coronation in Westminster Abbey. He also declined several opportunities to publicly swear allegiance to the new King. Llywelyn’s brothers contributed to the worsening relationship, assisting with local rebellions against Llywelyn’s rule and being granted sanctuary in England by Edward when they were forced into exile.

Money flowed intermittently from Wales to the Crown, and the Prince of Wales’s attempts to quell opposition and fortify his principality led to the building of new castles and extensions to existing battlements. From a high point of Welsh unity, Llywelyn’s rule over Wales was eroded until he was largely confined to the north-west territory of Gwynedd, his original fiefdom. Ten years on from the signing of the Treaty of Montgomery in 1267, Llywelyn’s principality was curtailed and under threat of being completely consumed by the English Crown. Edward’s armies had taken back Llywelyn’s territory, and the King’s castles began to encircle the Welsh. His grip on Wales was slowed only by an agreement in 1277 to end the fighting, and which stripped away much of the power that the Prince of Wales had managed to consolidate. He was allowed to keep part of Gwynedd and could retain his title, but the Prince had ceded control of the rest of Wales to Edward’s armies.

Nursing his reduced realm, Llywelyn continued with his agreed marriage to Eleanor de Montford and they were wed on the feast day of St Edward the Confessor, the patron saint of English monarchs, at Worcester Cathedral. The bride was presented to the groom by Edward I, who also paid for the feast. Despite the warring between them, this was a symbol of the accord that had seemingly been reached. The Prince of Wales finally paid homage to Edward I, but the celebrations at Worcester were the last hurrah for this souring alliance. One final conflict would finish off the last Welsh prince.

In 1282 the total conquest of Wales by Edward would be triggered not by the King or the Prince of Wales, but by Llywelyn’s brother Dafydd. The brothers had been reconciled after previous acrimony, but Dafydd was politically fickle and by 1281 he was both disillusioned by his brother’s pursuits and bitter about his own limited success. On Palm Sunday, Dafydd attacked Hawarden Castle, and then raided Rhuddlan Castle, while other rebellions broke out which sought to shake the remaining foundations of Llywelyn’s shrinking principality. It riled Edward, whose response was to stage a summer campaign to end the Welsh problem for good. Fighting broke out in several locations until a fleet of Edward’s ships captured the island of Anglesey, part of Llywelyn’s Gwynedd. The King’s troops ruined the harvest on the island, depriving Llywelyn and his men of food. Now besieged, the Prince of Wales was offered the opportunity to surrender to Edward. If Llywelyn agreed, he would be given an earldom in England on the condition that no Welsh prince would rule over Gwynedd again. Llywelyn refused to leave his people to the King’s mercy and declined the chance to live in English exile.

Llywelyn raged. ‘We fight because we are forced to fight, for we, and all Wales, are oppressed, subjugated, despoiled, reduced to servitude by the royal officers and bailiffs,’ he wrote to the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Peckham. The correspondence was clear, and as the archbishop relayed Llywelyn’s determination to the King, the Prince of Wales left the vulnerable Gwynedd to concentrate his court in Mid Wales. Llywelyn had been well-supported in the area, but on 11 December 1282 he arrived at Cilmeri near Builth Wells where an English army lay in wait.

Many stories survive about Llywelyn’s death, but it seems certain that Edward had placed the elimination of the Prince of Wales as the main objective of the war. He was killed near the River Irfon, a site now marked by a public house – the Prince Llewelyn Inn – and a stone monument often adorned with a Welsh flag and a floral tribute to Llywelyn the Last. While he was slain on this site, his body was mutilated and taken as a trophy. Llywelyn’s head was carried to London, to be viewed by the King as confirmation that the Prince of Wales was dead. With Edward’s approval the head was then mounted on a pike, and contemptuously crowned with ivy. It was immediately displayed in London and remained in place for a considerable length of time. The skull was said to still be atop a pike some fifteen years later. What remained of Llywelyn’s body was buried at the Abbey of Cwmhir, nestled among deep woods near Llandrindod Wells.

Dafydd ap Gruffydd

Prince of Wales 1282–1283

The end of Llywelyn was not the end of the line, with his brother Dafydd seen as the natural successor to the family fight to regain a principality led by a Welshman. While he maintained the rebellion against the Crown, Dafydd’s resistance only lasted six months. He was captured in the summer of 1283 and given the grizzly execution that would become the trademark treatment for those considered guilty of treason against the King: he was hanged at Shrewsbury before his entrails were removed and burnt, and his body split in four parts and sent to four English cities. It was one of the first recorded occasions of a person accused of treason being hanged, drawn and quartered for the pleasure of the monarch. The fate of the children of the Welsh princes was less gruesome but just as effective in ending the royal lineage. Llywelyn’s only child, his young daughter Gwenllian, was captured and sent to a convent in Lincolnshire where she would live until her death some fifty-five years later. She was a prisoner housed in a religious cage, a Princess of Wales exiled to the furthest reaches of England. Dafydd’s daughter was also dispatched to a nunnery, while his two sons were imprisoned at Bristol Castle where the eldest – heir to the Prince of Wales title – would die in what some deemed mysterious circumstances and others deduced was the result of malnutrition; the youngest son would remain captive in Bristol for decades, before he gradually disappeared from any further records.

That Edward would try so deliberately and so determinedly to end Llywelyn’s claim to the title of Prince of Wales is unsurprising; the extent to which he sought to round up, entrap and remove Llywelyn’s extended family links with the old principality speaks to the paranoia of the age. The prospect of further rebellion was almost guaranteed. Edward’s ruthless destruction of the Welsh royal court allowed him to keep the Prince of Wales title for those who would inherit the English Crown.

Edward II

Prince of Wales 1301–1307

It was no coincidence that the first Prince of Wales to be created by the King of England was born deep inside Welsh territory. Edward was the fourth son of King Edward I when he arrived in April 1284 at Caernarfon Castle. Two of his older brothers had died before he was born, while the third brother Alfonso would die later in 1284 leaving the baby Edward as sole heir to his father’s throne. The fortress in Caernarfon was still being built and would grow into an unavoidable reminder to the people of Gwynedd and beyond that an English monarch now ruled in place of their defeated Welsh leader. The completed Caernarfon Castle did not have the more overt defensive capabilities of Harlech and Beaumaris which formed part of the Iron Ring of Edward’s network of Welsh castles. But Caernarfon’s sheer size allowed it to become a seat of power and crushing dominance over the subdued and reluctantly submissive Welsh.

The King and his Queen, Eleanor, had spent most of the previous summer at Caernarfon as intensive construction work was underway, so there was a chance the young Prince was conceived there too. The time and place of the Prince’s birth, and potentially his conception, were politically serendipitous to the ongoing narrative of the English Crown. The new Prince Edward arrived two years after the death of Llywelyn, and a year after the siblings and offspring of the Welsh Court had been killed or contained. While he would not be created Prince of Wales until he was seventeen, the young Edward’s birth in the crucible of Welsh resistance could not have been more auspicious for the Crown’s campaign. The birth of the Prince, and the expansion of Caernarfon Castle, did not crush Welsh resistance. The Middle Ages were peppered with skirmishes and bloody battles across swathes of Britain, Ireland and France which contributed to a rather restless childhood for Edward. Dermot Morrah wrote that ‘the royal nursery was a peripatetic affair, the young Lord Edward and his five sisters (no more boys were born) being carted about in the wake of the King in his constant journeying to Wales, to the Scottish Border, and on frequent progresses about his English realm’. By 1300 and still a teenager, Prince Edward fought with his father on a campaign in Scotland. His father created him Prince of Wales in 1301, partly to exert further authority over a corner of the realm that still bubbled with resistance. Six years later he became King Edward II.

The tradition of creating a Prince of Wales for every first-in-line did not begin with Edward II but with his grandson, Edward of Woodstock, the Black Prince. He was thirteen when, on 23 May 1343 his father King Edward III invested him as Prince of Wales. Edward III had never been given the title, and so history records that the Black Prince was the first of what Dermot Morrah calls the ‘continuous history of the English Princes of Wales’. Despite the pageantry and officialdom surrounding the monarch’s use of the title, there would be one final Welsh claim to be Prince of Wales.

Owain Glyndwˆr

Over a century after the death of Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, one man made certain that the memory of the Welsh princes had not been wiped from the national consciousness. The endless attempts to repress and subdue the Welsh had granted English kings a level of dominance over Wales and its people that the native princes had failed to accomplish themselves. It had left the population feeling oppressed, and they longed for a new Welsh leader to present himself and represent them. Owain Glyndwˆr’s rising in the fifteenth century managed to establish more order and authority over Wales than any native prince had achieved in hundreds of years.

At Glyndyfrdwy in north-east Wales a small crowd gathered on 16 September 1400 to create Owain ap Gruffydd, or Owain Glyndwˆr, the new Prince of Wales. He was a man with the military skill to beat back the colonial army, while maintaining enough political diplomacy to unite local Welsh lords and rebel leaders in support of his cause. The Welsh had watched Edward I and his heirs exerting power after the death of Llywelyn, and had witnessed the crushing and controlling effects of the castle construction and land-grabbing. Famine and plague worsened what must have been a fairly miserable existence, with failed harvests and the Black Death instilling rebellious anger in those who had yet to succumb to starvation or disease. As well as famine and plague, social tension was spurred by some of the harsh laws that Edward I had imposed on the Welsh population. The English came to populate the towns that grew around the new castles in Conwy and Caernarfon, and they were given special rights that formed part of the economic element of this military conquest. Only the English could trade within the walled towns around Edward’s new castles, with the Welsh kept as outsiders in their own land.

Owain Glyndwˆr was in his forties when the stars almost literally aligned for him at the turn of the fifteenth century. He was a member of the Welsh nobility, and could trace his lineage back to the royal rulers of Wales before Edward. Through marriage he was related to the Gwynedd princes, while his father’s family were descended from the twelfth-century princes of Powys Fadog in Mid Wales. Through his mother, Glyndwˆr was descended from the Princes of Deheubarth in the South West. His pedigree allowed him to claim regal connections across Wales and gave him authority among those who remembered the various Welsh principalities as he embarked on a campaign to reclaim the territory and become a Prince of Wales himself. He was buoyed by a tradition of Welsh political prophecy, heightened by the appearance of a comet in the skies at that time. Anybody reading the runes in medieval Wales could easily place Glyndwˆr at the heart of a great rebellion, with soothsayers foreseeing that he could reclaim land and dignity for the people of Wales after their subjugation at the hands of English kings and non-native Princes of Wales. The mythologising of Owain Glyndwˆr began before his campaign and would continue for centuries after his defeat. He was a prodigal son who understood his Welsh heritage, while his land-owning under the Crown gave him useful insight into the English colonial attitude. And, like Llywelyn before him, Glyndwˆr also saw an opportunity to strike while the Crown was weakened by events in England. Richard II had been deposed in 1399, the raging King overthrown by Henry Bollingbroke – Henry IV – who had schemed to take control of the royal court.

Glyndwˆr’s land in North and South Wales gave him wealth, and he held a court at Sycharth near Llangollen in north-east Wales which had a legendary splendour. The poet Iolo Goch, to whom Glyndwˆr was a patron, composed works in honour of his master and his household that described the gardens, orchards and vineyards that surrounded a manor house of great architectural standard. After Glyndwˆr was elevated to be the Prince of Wales in 1400 by the noblemen at his other court, Glyndyfrdwy, he launched a revolt against English rule that would see his lands forfeited in the pursuit of freedom. The rebellion peaked around 1406 when his men captured key battlements in Aberystwyth and Harlech.

Alongside the military victories, Glyndwˆr also sought to establish his vision for an emerging Welsh state. France had backed the rebellion, and in a letter to the French King Charles VI in March 1406, Owain Glyndwˆr asked for continued support in ridding Wales of its English monarch. It was composed in Pennal, a settlement near the north bank of the River Dyfi on the southern edge of Gwynedd. The letter is a unique record of the potential structure of an independent Wales in the Middle Ages. Known as the Pennal Letter, Glyndwˆr’s words were written during a meeting of the Welsh church. Glyndwˆr said he would swear allegiance to the Pope of Avignon, rather than the Pope in Rome, in return for the establishment and recognition of a formal Welsh church. The Bishop of St Davids would lead a communion whose catchment would spread as far east as Lichfield and Bath. After brutal battles against the English, it was this vision of a decolonised Wales which Glyndwˆr presented as the future fruits of his endeavours. Universities would be established in North and South Wales, and he called for the French monarch’s support in repelling the English and fortifying a resurgent Welsh nation. But further French support evaporated more quickly than the dream of an autonomous Welsh nation.

In his meditation on Welsh nationhood, When Was Wales?, the writer and film-maker Gwyn Alf Williams outlined Glyndwˆr’s ability to unite a basket of grievances and ingrained wrongs.

It was a quarrel in the March which ignited a race war; it was a civil war; it was an explosion of anger and hatred from the unfree and oppressed; it was a peasant jacquerie; it was a rebellion by rising squireens against the restrictions of an archaic regime; it was a revolt of frustrated intellectuals within the church; it was a feudal war to create some kind of Burgundy within Britain. These all fused, like so many rebellions we have seen since, into a war of national liberation against a colonial regime riddled with contradiction.

And yet the many fronts and numerous causes that had spurred his rebellion were beginning to lose their momentum. In the same year that Glyndwˆr composed the Pennal Letter, his grip on Wales was loosening. From 1406 territory was lost and some parts of Wales asked for pardons from the King, though it was not the end of Glyndwˆr. His campaigns continued sporadically, but this was a rebel on the run and not a princely hero. He faded into the background, with no record of his rebellion after 1415.

The absence of a public spectacle around his death allowed those Welsh who had prophesied his rebellion to romanticise his disappearance. He had been a leader with a vision for Wales and had briefly succeeded in continuing the ambition of Llywelyn that had been so forcefully crushed by Edward I some hundred and thirty years earlier. He was a modern, European leader with a plan for Wales that would not be realised again until the election of members of the National Assembly in 1999. Glyndwˆr’s strength was ultimately in his ability to remain in the national consciousness, to keep alive the memory of a fighting nation which rebelled for almost fifteen years. The man has been transformed from an historical figure into an almost mythological leader, the ultimate Welsh patriot and an inspiration for modern Welsh nationalism. Most of the other Welsh princes had been focused on gripping power and taking land, but Owain Glyndwˆr was a leader with a much broader vision to enrich the principality he ruled. While he succeeded in reviving the ideas of a Welsh nation after the death of Llywelyn, the death of Owain Glyndwˆr was the end of the true last native Welsh Prince. With his disappearance, the very idea of a Welsh monarchy died forever.

Every Prince of Wales since Owain Glyndwˆr has been created by the Crown, an institution that has clung to the tradition of bestowing that title on the first-in-line despite happily discarding all sorts of anachronistic decorations over the centuries. The monarchy has frequently modernised to meet changing tastes or challenging circumstances. Yet despite the executions, the merging of the English and Scottish Crowns and the creation of a House of Tudor from Welsh roots, the Prince of Wales has remained the creation of an English and latterly a British monarchy whose foundations cling to a thousand years of history. Its colonial footprints stretch around the world, but the conquering of the Welsh created a trophy that would become symbolic of the continuity of the monarchy. The existence of a Prince of Wales reaffirmed the hereditary principle, decorated the next-in-line and hallmarked the pedigree. Its use has sometimes waned over the centuries, as monarchs changed more quickly than in recent history or in the absence of a male heir. But throughout its creation by the monarch, the title-holders had given very little concern for Wales or any calling to care for the Welsh. Only with the arrival of Charles, and his elevation to be Prince of Wales, did the title-holder show a compassion for the Welsh people that would rival the loyalty shown by Owain Glyndwˆr, whether they wanted it or not.

Charles was born at 9.14 pm on 14 November 1948 at Buckingham Palace. Crowds had been building outside throughout the day, finding vantage points on the Victoria Memorial and growing deeper in number against the railings. The Duke of Edinburgh, having become restless at the length of time it was taking for his first child to emerge into the world, ‘changed into flannels and a roll-collar sweater’ and went to the palace squash court with his private secretary, according to Dermot Morrah. By the evening there were a few thousand people outside, with police officers clearing a space in the crowds for doctors and midwives whose arrival signalled the imminent appearance of a prince. The Duke was still playing squash when he was told that he had become a father. At almost midnight a notice was placed on the palace railings announcing that the Princess Elizabeth had safely delivered a son. On the BBC light programme the announcer Franklin Engleman broke the news. ‘It has just been announced from Buckingham Palace that Her Royal Highness, Princess Elizabeth, Duchess of Edinburgh, has safely delivered a prince at 9.14 pm and that her Royal Highness and her son are both doing well. Listeners will wish us to offer their loyal congratulations to Princess Elizabeth and to the royal family on this happy occasion,’ he declared in a crisp BBC voice.

After midnight a police car with a loudspeaker sought to hush the crowd as the first baby to be born in Buckingham Palace for sixty-two years risked being kept awake by the revellers outside. Morrah’s impeccable account of the night recalls the loudhailer repeating countless times: ‘Ladies and gentlemen, it is requested from the palace that we have a little quietness, if you please.’ The singing crowds drowned out the announcements.

While the numbers thinned, the news spread around the world. Pre-prepared telegrams were sent to governors and ambassadors overseas, while the newspapers set to work reporting the evening and predicting the little boy’s future. They speculated intently about his education, which armed forces he might join and what type of king he may become. Few, if any, journalists appeared to spend time discussing what the boy may do in the years before his accession to the throne. None would have predicted that Charles could spend almost a lifetime as heir, and why would they? The reigns of monarchs had been remarkably short. When Charles was born his grandfather would last another four years as King before dying of cancer in 1952. He had reluctantly taken the throne in 1936 when Edward VIII lasted three hundred and twenty-five days in the role. Before that there was George V: sixteen years, and Edward VII: nine years. Had the newspaper columnists looked to Victoria (almost sixty-four years) then the prospect of a female monarch in Elizabeth II may have led them to realise that this newborn future King faced a significant wait before his regnal qualities could be assessed.

A month after his birth the baby boy was christened in the music room at Buckingham Palace. Charles Philip Arthur George was baptised by the Archbishop of Canterbury with water from the River Jordan. It was the moment at which Charles was tethered to a Christian faith which he would vow to defend at the moment of his coronation. While some royal traditions were essential, some practices were modernised. By the time he was eight years old, and his mother had become Queen, Charles was sent to school. Private tutors had been preferred by royalty, their offspring seemingly above attending even the best schools until the middle of the twentieth century. At Hill House, then a small prep school in London, Charles’s teachers and pupils were encouraged to address him by his first name and to treat him as any other boy in class. He was the only boy to be raised in a palace, and despite efforts by his parents and nannies to keep him grounded, there were some experiences the young Prince could not relate to. This included the idea of going to a shop, as Dermot Morrah’s well-informed book on Charles’s schooling described how ‘he knew nothing about money and never handled it. One of the first tasks of the school was to teach him the values of these various bronze and cupro-nickel discs with his mother’s head on them. And it was not until six months after he went to Hill House that he made his first journey on a bus’.

A few months later he was wearing the uniform of a new school. An embroidered ‘C’ marked the centre of his royal-blue school cap, not for ‘Charles’ but for Cheam School in Berkshire. His first term was notable for an early accusation of press intrusion – dozens of newspaper stories remarked on his school days, his companions and his teachers. An intervention by the Queen’s press secretary put Fleet Street on notice, and the attention then focused only on newsworthy matters. Happily, one presented itself for the papers and the Prince in the summer of 1958.

The Queen had been due to attend that year’s British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Cardiff, but a recurring bout of sinusitis kept her under medical supervision in London. Instead, the Duke of Edinburgh deputised for the monarch at the official opening on 18 July. A new Wales Empire Pool had been constructed in Cardiff’s city centre for the event. Boxing and wrestling events were held at Sophia Gardens across the River Taff, while cyclists raced around Maindy Stadium. By the end of the competitions, England topped the medal table while Wales managed a respectable eleventh place out of the thirty-six nations and territories to take part. The boxer Howard Winstone secured the host country’s only gold medal.

Over forty thousand people crammed into Cardiff Arms Park for the closing ceremony on Saturday 26 July 1958. The Band of the Welsh Guards played ‘We’ll keep a welcome in the hillsides’ and ‘Auld Lang Syne’ as the teams paraded around the stadium, drowned out briefly by the roar of an RAF fly-past. The band would also play God Save the Queen for the guest of honour, and while she was not there in person, the Queen did record a message to be played to the crowd. Prince Charles and some of the other boys at Cheam School were invited to the headmaster’s study to watch the ceremony on television. In the stadium, and on the tiny black-and-white set, the Queen’s voice closed the event with a sensational twist:

The British Empire and Commonwealth Games in the capital, together with all the activities of the Festival of Wales, have made this a memorable year for the Principality. I have therefore decided to mark it further by an act which will, I hope, give as much pleasure to all Welshmen as it does to me. I intend to create my son, Charles, Prince of Wales today. When he is grown up, I will present him to you at Caernarfon.

It was a moment of acute embarrassment for Charles, his face flushing as his friends turned to congratulate him. ‘I remember thinking, “What on earth have I been let in for?” That is my overriding memory,’ Charles would later recall. He told his biographer Jonathan Dimbleby that the moment of the announcement confirmed the ‘awful truth’, and that his fate was sealed. He was nine years and eight months old, but already realised the enormity and, perhaps, the loneliness of his position.