20,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

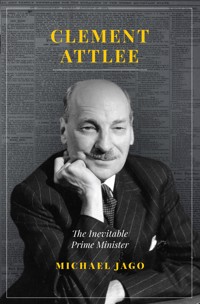

Elected in a surprise landslide in 1945, Clement Attlee was the first ever Labour leader to command a majority government. At the helm for twenty years, he remains the longest-serving leader in the history of the Labour Party. When he was voted out in 1951, he left with Labour's highest share of the vote before or since. And yet today he is routinely described as 'the accidental Prime Minister'. A retiring man, overshadowed by the flamboyant Churchill during the Second World War, he is dimly remembered as a politician who, by good fortune, happened to lead the Labour Party at a time when Britain was disillusioned with Tory rule and ready for change. In Clement Attlee: The Inevitable Prime Minister, Michael Jago argues that nothing could be further from the truth. Raised in a haven of middle-class respectability, Attlee was appalled by the squalid living conditions endured by his near neighbours in London's East End. Seeing first-hand how poverty and insecurity dogged lives, he nourished a powerful ambition to achieve power and create a more egalitarian society. Rising to become Leader of the Labour Party in 1935, Attlee was single-minded in pursuing his goals, and in just six years from 1945 his government introduced the most significant features of post-war Britain: the National Health Service, extensive nationalisation of essential industry, and the Welfare State that Britons now take for granted. A full-scale reassessment, Clement Attlee: The Inevitable Prime Minister traces the life of a middle-class lawyer's son who relentlessly pursued his ambition to lead a government that would implement far-reaching socialist reform and change forever the divisive class structure of twentieth-century Britain.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 821

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

CLEMENTATTLEE

THE INEVITABLE PRIME MINISTER

MICHAEL JAGO

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am greatly indebted to a large number of people who have contributed in innumerable ways to the completion of this book.

Above all, members of the Attlee family have been generous with their time and helpful in correcting errors of emphasis and fact. Pre-eminent among these has been Anne, Dowager Countess Attlee (daughter-in-law), the keeper of the archive and the flame. Her comprehensive collection of photographs, memorabilia and memories provided many happy hours in her ‘Clement’ room. I am also indebted to the 3rd Earl Attlee (grandson) for his hospitality and willingness, amid House of Lords business, to spend time with me. Additional help was provided by Air Vice-Marshal Donald Attlee (nephew), Tom Roundell Greene (great-grandson), Jo Roundell Greene and Jenny Lochen (granddaughters), and Charles Attlee (great-nephew), who helped me set the family wheels in motion.

The book has been read, either in its entirety or in part, by Dr Patricia Owens (University of Sussex), Dr Robin Darwall-Smith (University College, Oxford), Michael Parsons (University of Pau), Dr Daniel Lomas (University of Salford), Olivia Harris (Middle Temple), Chris and Frances Pye, Bryan Engler, Robin Martin, by Anne, Lady Attlee, and by long-suffering members of my family. Their help and suggestions have been immeasurable. Dr Darwall-Smith, archivist of ‘Univ’, additionally opened the University College archives for inspection. Naturally, any errors of fact or omission are mine alone.

Research was also greatly aided by Simon Fowler, formerly of the Public Records Office; Helen Langley, Rebecca Wall, Dr Anne Mouron, and the staff of the Special Collections Reading Room at the Bodleian Library; Julian Reid and Harriet Fisher, archivists at Corpus Christi College, Oxford; the Librarian and staff of Churchill College, Cambridge; Edmund King, late of Wadham College, Oxford; Sam Mallinson of Brasenose College, Oxford and Jon Roycroft of the University of Oxford; the Librarian of the Oxford Union; by Bill and Jean Whaley, who provide a home for authors visiting Oxford, and by Toby Parker, archivist at Haileybury College.

Additionally, in various ways, the following have provided invaluable input and support: Edward Cootes, Professor Jonathan and Sarah Dancy, Iain Harris and Juliet Jamieson, James and Dr Elizabeth Jago, Claire Jamieson, Major Dr Seth Johnston (US Army), Richard Savage, Jerry and Jane Scott, Robin and Amanda Shield and Mark Vandevelde of the Financial Times. Much of the book was written in France, where I must thank Benoît Pelletier and Chantal Pourget for maintaining order in my house and affording the same respect for calm that they would have afforded Marcel Proust.

For help in locating photographs I must especially thank Will Carleton of Press Photo History. For help and permissions I am grateful to Anne, Countess Attlee; Michael Rhodes representing the Ernest Fawbert Collection; Charlie Masson-Smith, Chief Press Officer of Wandsworth Council; Colin Panter of Press Association Images; Mark Blumire of Alpha Press; Simon Flavin of the Daily Mirror; John Balean and Mark Dowd of Top Foto; Laura Wagg of PA Images; and Darryl Lundy of The Peerage.

As ever, I am in the debt of my agent, Andrew Lownie, and of Mick Smith and Olivia Beattie of Biteback Publishing who have provided encouragement and a remarkable degree of tolerance as deadline after deadline slipped by.

Somehow, in the midst of a heavy lecture schedule, my wife Carol has found time to read each chapter; her comments and suggestions have added felicity of expression and a transatlantic perspective to my efforts.

Finally, I must offer belated thanks to the late Edric William Hoyer Millar CBE and the late Thomas Simons Attlee for stimulating the interest of the author, then a twelve-year-old boy, in the 1945–51 Labour government. It is to the memory of those two outstanding gentlemen that I dedicate this book.

CONTENTS

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

When I adduced the subtitle ‘The Inevitable Prime Minister’, my intention was to gainsay the myth that Clement Attlee came from nowhere, that his elevation in 1945 was an accident or electoral mistake. More than any party leader in the twentieth century, he earned his status, and more than any member of the War Cabinet, except Winston Churchill himself, he contributed, without a hint of partisanship, to the national cause.

Thus, given that Britain was at peace in 1945 and that the electorate wished for change, and given that Clement Attlee was the established leader of the party of change, it was hardly surprising that, after a decade in that role, he replaced the redoubtable Churchill at the helm.

Unsurprisingly, the word ‘inevitable’, applied to Clement Attlee’s path to Downing Street, drew a reaction of surprise from critics. John Bew pointed out that nothing is inevitable, and Jack Straw, in a comprehensive and sympathetic lecture to the Middle Temple in 2015, took issue with the word as though it somehow devalued the premiership of a remarkable, unique man.

Since 1945, the Churchill legend has waxed and waxed. That is hardly surprising as, absent that indefatigable pugnacity, the Second World War might have taken a very different course. That alone could be used to demolish the idea that the events of 1945 were ‘inevitable’.

But if we take the outcome of the war as established historical fact, consider the electorate’s desire for change in July 1945, and look back at the evolution of the Labour Party in the preceding two decades, the outstanding figure, the only electable leader, in place since 1935, was Clement Attlee. It was no accident or temporary wave of populism that ushered in six remarkable years of his leadership.

Within the Labour Party, moreover, not every observer agreed with that causality. Even as Attlee prepared to kiss hands with King George VI in July 1945, Herbert Morrison was agitating to replace him. Principally because of the unwavering support of Labour’s strong man Ernest Bevin, Morrison’s machinations were circumvented. Not inevitable, perhaps, but when Violet Attlee drove their modest saloon car to Buckingham Palace, it was the correct, the only sensible outcome.

In a little under forty years, the Labour Party had developed from a fringe party that boasted one charismatic Member of Parliament to a movement that achieved a landslide victory with nearly twelve million votes and 393 seats in 1945. Along the way, the party’s leadership had seen a variety of individuals and a shifting platform as Keir Hardie, George Lansbury and Ramsay MacDonald experimented with different ideological clothing. From the mid-1920s onwards, Attlee had been at the ideological and strategic centre of the party. His confirmation as leader in 1935 was, if not inevitable, logically entailed.

From 1935 to 1945 there was a single thread that dominated the course of events: how Britain would respond to the mounting territorial ambitions of Nazi Germany. Once again, Attlee was consistent, first as the Leader of the Opposition, later as a member of the War Cabinet and, from 1942, as a busy and massively supportive Deputy Prime Minister. Time and again, as Churchill’s missions kept him at Placentia Bay, Casablanca, Tehran, Yalta, it was Attlee who chaired the War Cabinet and corralled ministers’ support for the PM.

To his brother Tom he wrote that ‘it is obviously futile to try to put on Saul’s armour’ and that he was ‘holding the baby’ and would not try ‘to stretch the bow of Ulysses’. His unimpeachable loyalty to the cause, first of the party, later of an embattled nation, uniquely qualified him to lead the party and the nation when the need arose.

From this sequence of events, this evolution of the Labour Party and the role of its leader, comes the statement that Attlee’s elevation was ‘inevitable’. Granted that events could have derailed that progress, granted that from 1940 to 1944 Britain’s fate itself hung in the balance, but on the premise that after Pearl Harbor the defeat of Germany was inevitable, no force could keep Labour from power. Ipso facto, Morrison and Laski notwithstanding, there was no movement powerful enough to keep Attlee from Downing Street.

INTRODUCTION

Taking tea at the House of Lords – Indian tea and digestive biscuits – with the 3rd Earl Attlee, I look across the table at a remarkable incarnation. Stouter than his wiry grandfather, as follically challenged on the crown of his head, sporting a trim military moustache, given to smiling definitively at the end of a sentence, John Attlee has not only the appearance but also the mannerisms of his grandfather. I expect him to pull out a well-chewed pipe and fill it with Golden Bar tobacco at any moment.

Unlike Clement, he was not a career politician, but, like his grandfather, had many years outside politics before he entered the House of Lords on the premature death of his father, Clement’s only son, in 1991. ‘It was vital experience,’ he recalls. ‘One thing led to another and each step prepared me for the next. Too many politicians and civil servants have never set foot outside the safety of the system, never had to run their own business.’ I smile, for by the time Clement Attlee stood for Parliament in 1922 he too had a wealth of different experiences. And every step that he took from then until 1945 seemed planned to prepare him for the next. There was an inevitability about his path to 10 Downing Street.

‘How would he have fitted into today’s House of Lords?’ I ask. ‘Like a glove,’ my host replies. And how about today’s Labour Party? That’s a different matter. Clement, whose later years were devoted to world government and a quest for world peace, might not have treated Iraq in quite the way that Tony Blair did. ‘Harold Wilson kept us out of Vietnam,’ says Lord Attlee. ‘Why did we go to war in Iraq? Clement and Blair would not have seen eye to eye on that war.’

John Attlee answers questions in the same way, albeit more loquaciously, as the famously taciturn Clement. He considers his answer, fits it into historical context and gives a succinct reply. I asked what memories he had of his grandfather, thinking that perhaps he deliberately imitated his manner. ‘Very few,’ he replied. ‘We were living in Belgium when I was a boy. I would be picked up at Heathrow by Laker1 and taken to lunch in the Temple. Then Laker would drive me to Victoria for the train to prep school.’ Born in 1956, the present Earl Attlee knew only the last years of Clem’s life.

For an hour and a half we talk about John’s life in politics, how he spent a while as a crossbencher before joining the Conservative Party, how he might easily have followed his grandfather into Labour’s ranks if he had been asked. (‘Tony Blair has enormous charm and I’m sure he would have persuaded me if he’d wanted to.’) How he rose to be a government whip in the Lords and what the job entailed. Again, there was a directness in the telling of the story that was reminiscent of his grandfather.

At one point the images fused and I asked him why the government had not pressed its plans for reform of the House of Lords, how they had missed that opportunity. A pardonable confusion followed and I had to explain that I meant the 1949 proposals. For a moment I must have believed that I was talking to the 1st Earl.

The Houses of Parliament are majestic and it is easy to imagine oneself in another century. This augments my sense of being transported back to the thrilling days of 1945, when the first majority Labour government came to power, of being a witness to the remarkable years of the Clement Attlee administration. A devoted parliamentarian, he spent thirty-three years in the House of Commons, twenty of them as leader of the Labour Party. When he stepped down in 1955 and was awarded an earldom he became a regular attender at the House of Lords, dutifully taking the train and Underground each day to St James’s Park. As much as any Prime Minister, Clement Attlee had an undying faith in Britain’s parliamentary system.

British peers tend to be men and women of a certain age and I imagine that I am seeing not the lords of today but Christopher Addison, Pethick-Lawrence, ‘Wedgie’ Stansgate, Jowitt, the peers of the 1945–51 Labour government. That my host is a Conservative blurs the image not at all. For Clement Attlee, socialist to his fingertips, was far from being a radical. At times he must have envied Ernie Bevin, Herbert Morrison and Aneurin Bevan their humble origins. No less must he have envied their more charismatic styles. Bevin, a larger-than-life figure, doggedly English and unashamed to refer to Nuits Saint Georges as ‘Newts’, was by far the most visible of the Cabinet. Morrison, ‘the Cockney sparrow’, had a shrewd ability to appeal to the common man’s concerns, while Bevan’s cheeky brilliance appealed to a broad-based constituency. Attlee, by contrast, never quite shed his middle-class Victorian upbringing. Gladstonian Liberal principles learned in sober, secure Putney never quite vanished from his make-up. For all his reforming zeal and his pride in his government’s achievements in India and the shift from Empire to Commonwealth, Clement Attlee was a Britain-first patriot in the tradition of Joseph Chamberlain and Leo Amery.

Two long periods of Labour administrations have intervened since 1951, when Clement Attlee’s government fell from power, and those administrations were very different from their post-war predecessor. By 1964, when Harold Wilson became Prime Minister, Clement Attlee was already a man of the past, a pre-war relic in the ‘white heat of technological revolution’. And, as his grandson points out, he would have hardly have been at ease with the micromanaging central control of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. He might very easily have taken the same path as Roy Jenkins, Shirley Williams and David Owen in 1981. Shadows of three more former Labour Party peers flit across the neo-Gothic fabric of the House of Lords.

Two hours have slipped by while I juggled past and present. As I step out into a dark November evening, I imagine the fog swirling about Parliament Square and a news vendor calling out, ‘India partitioned. Read all about it.’

John’s grandfather Clement Attlee is the man most applauded (or blamed) for the partitioning of India, Britain’s ‘Jewel in the Crown’. As Prime Minister of the first majority Labour government from 1945 to 1950, the slight, angular figure (‘Little Clem’ or ‘the little man’, as Ernest Bevin fondly referred to him) led a government that transformed Britain after the Second World War. The achievements of that administration, of which the granting of independence to India is perhaps the most famous example, have become legendary. The landslide election of 1945 is perceived as the yardstick against which subsequent elections are judged; Clement Attlee, who became the 1st Earl Attlee in 1955, as commanding general of that remarkable victory, has become a cult figure.

Few of his colleagues would have predicted such elevation when he became deputy leader of the Labour Party after nine years as a Member of Parliament. Even when he succeeded to the leadership in 1935 it was widely assumed that he was a stop-gap leader, soon to be replaced by the better-known Herbert Morrison or Stafford Cripps. Indeed, even as he prepared to ‘kiss hands’ with the King after the election victory of 1945, several of his colleagues were conspiring to replace him with Morrison as leader and, therefore, as Prime Minister. His rise was attributed to good fortune rather than ability. He remained something of an enigma to the electorate; as time went on, the legend grew up that he was somehow an ‘accidental’ Prime Minister, a caretaker who inexplicably remained in situ and led the Labour Party for twenty years.

Neither of the two widely different images of Clement Attlee – as an infallible socialist icon to be venerated, or as a fortunate interloper – is wholly accurate. His style of leadership was distinctive, though occasionally flawed; his rise to power was neither accidental nor surprising. He was an ambitious man with a clear mission; he differed from his predecessor Winston Churchill in that he governed not as a charismatic champion on a charger but as chairman of a Cabinet. But the suppression of individual persona indicated no lack of ambition or purpose.

On occasion, that modest man became the legatee of the unfortunate appointments he made. Even in the departure from India in 1946–47 – perhaps especially in that episode – Attlee found that the going was appallingly slow, principally because the wrong man occupied a key position. It was a pattern that repeated itself throughout his six years as Premier.

Yet by the time the Conservatives returned to office in 1951, far-reaching, radical reform had been achieved at a breathtaking pace. The legacy of Attlee’s government formalised the shape of the post-war consensus that survived until the Margaret Thatcher era nearly forty years later. For those reforms Attlee cannot take sole credit, but his ability to consume official business at stunning speed, his skill and diplomacy in keeping in harness a disparate, vocal group of able men, his relentless drive to bring projects to conclusion without compromise of principle – all these qualities combined to create a redoubtable leader. As Bevin famously commented in 1950, ‘Clem never put forward a constructive idea in his life, but no one else could have kept us all together.’2

Without doubt the elevation of Attlee to cult status contains an element of nostalgia. The triumph of politics since Attlee’s heyday brings with it a wistful contemplation of a Prime Minister motivated by the highest principles: patriotism, loyalty, decency in the internecine Labour Party, meticulous honesty in his dealings with politicians of all parties. Even his removal from office can be attributed to an altruistic motive: he insisted that an early election be held before King George VI set off on a tour of the Commonwealth, as he was adamant that the monarch’s tour should not be vitiated by concerns about the state of his government in Britain. In this light Attlee becomes less a cult figure than a symbol of political decency that may have vanished for good. As to his rise to power, it was achieved entirely on merit, aided, it is true, by the tergiversations of Ramsay MacDonald’s government, by the electorate’s dim view of the Tory Party of the 1930s, by the absence from the House of Commons of his Labour Party rivals at critical moments.

Closer scrutiny reveals a committed patriot who returned from service in the First World War and, most wisely, retained his military rank, becoming affectionately known in his East End constituency as ‘the Major’; a Member of Parliament who earned the deepest respect of his parliamentary colleagues between 1931 and 1935; a dedicated and competent Deputy Prime Minister in the coalition government during the war of 1939–45. Just as he had won the loyalty of the Parliamentary Labour Party, he earned his spurs in the wider Labour movement despite his lack of proletarian origin. By the end of the Second World War he had won the respect of the electorate, having been the voice of the government when Churchill was absent – as he frequently was.

At every critical point in his rise to power, Clement Attlee was simply the right man in the right place at the right time. Napoleon, it is true, would have approved of him, for he had that virtue that Bonaparte valued most in a general – he was lucky. It was greatly more than luck, however, that thrust power upon him. As Frank Field has astutely observed,3 his later writings after he stepped down as Labour leader illustrate most clearly the ethical values that he brought to the exercise of politics and power. He led by example and was never ashamed to do so.

His tenure of power, sandwiched between two periods when Winston Churchill occupied Downing Street, inevitably results in comparisons between the two very different men who handled the business of being Prime Minister in widely different ways. General Sir Ian Jacob remembered that to Churchill ‘what mattered most … was not so much that he was Prime Minister and Minister of Defence as that he was Minister of Defence and Prime Minister … He saw himself first as the man running the war, and second as the Prime Minister.’4 While Attlee for a brief period occupied both those offices on first attaining power, it is definitively not as a head of a government department that we think of him. In the pre-war Labour government his most visible ministerial role was as Postmaster General. When Sir Stafford Cripps plotted to unseat the Prime Minister in 1947, his proposal that Attlee should become Chancellor of the Exchequer was absurd.

It was as Prime Minister that he excelled; by skilful and patient management that he governed. Bevin was correct in his assessments of himself and his colleagues, identifying Attlee’s ability to sum up the majority view of his Cabinet with succinct accuracy, and concluding that no other of his colleagues could have done the job.

In no sense was Clement Attlee an ‘accidental’ Prime Minister. As one traces his path from Haileybury to Oxford to the Inns of Court and his first visit to the East End of London, as we fit together his family’s commitment to social service, his wartime record, his passionate view of the obligations (and the limitations) of a socialist government and his contributions to that goal, his rise becomes not accidental but inevitable.

ENDNOTES

1 Alfred Laker, his grandfather’s manservant from 1964 until Clement’s death in 1967.

2 Leslie Hunter, The Road to Brighton Pier, p. 26.

3 Frank Field (ed.), Attlee’s Great Contemporaries. 2009, London: Continuum Books.

4The Observer, ‘Churchill By His Contemporaries’, p. 70.

CHAPTER ONE

A VICTORIAN UPBRINGING, 1883–1904

Clement Richard Attlee was born on 3 January 1883 into a large Victorian family in a large Victorian house, ‘Westcott’, in Portinscale Road in the village of Putney, six miles from central London, a haven of peace and respectability. For twelve years a child had been born at regular intervals of two years to his parents, Henry and Ellen Attlee. Clement was the seventh child, the fourth boy; late in the following year another boy was born and the family of eight children was complete. It was a close-knit family, conformist, God-fearing, modestly prosperous, socially secure with no ambition to rise further. The family attended church at least twice every Sunday; each morning, family and live-in servants gathered for morning prayers at 7.30. Ninety minutes later Henry Attlee took the train to his place of work, the solicitors Druces and Attlee. Each evening he drank one glass of claret with dinner before withdrawing to his study to prepare his work for the following day.1

Family tradition has it that the Attlees originated at Great Lee Wood, north-west of the village of Effingham. There are traces of a moat in Lee Wood which enclosed the manor of Effingham-La-Leigh, mentioned in local records as early as AD 675. The Domesday Book lists the manor as held by the manor of Wotton, owned by Oswold de la Leigh; in 1320 it passed into the estate of Effingham Place Court and thence to the Crown. Henry VIII often rode the dozen miles from Hampton Court to hunt there. In 1550 Edward VI granted the manor to Lord William Howard, in whose family it remained until the eighteenth century. In the 1920s Effingham Golf Club was built on the land of the original manor.

Lee House (or ‘Leigh House’), part of the landholding of Effingham Place Court, was not only the home of the family but also the origin of their name – ‘At the lee’ becoming ‘Attlee’ and accounting for the curious double ‘t’.2 They were long-established as tenant farmers in Effingham and by the early eighteenth century they had moved the short distance to Dorking, establishing a milling business at Rose Hill and living in Westcott, a village to the south-west of the town. Not only did Henry Attlee rename his first two homes in Putney ‘Westcott’ as a memento of the family’s source of affluence, Clement used the name for the house he later built near Great Missenden, and his sister Mary for her house in South Africa.

By the late eighteenth century the mill was prosperous. Richard Attlee, father of seven sons, accommodated two in the milling business, set two up as brewers and provided an allowance for Henry, Clement’s father, to be articled at the age of sixteen to Druces, a firm of solicitors in the City of London. Henry became senior partner, adding his name to create ‘Druces and Attlee’, a firm that exists today under the umbrella of Druces LLP, a thriving commercial law firm, still based in the City. Henry’s career flourished and he rose to be president of the Law Society.

After twelve years with Druces, Henry was sufficiently established to marry Ellen Bravery Watson, 23-year-old daughter of Thomas Watson, secretary of the Art Union of London. Established in 1837 ‘to aid in extending the love of the Arts of Design within the United Kingdom, and to give encouragement to artists beyond that afforded by the patronage of individuals’, the Art Union was a successful and enterprising society. By 1865 there were over 15,000 subscribers and in 1867 Curiosities of London recorded that it had, ‘unquestionably, fostered a taste for art’.3

Ellen, the oldest of six children, managed the Watsons’ house on Wandsworth Common and brought up her younger siblings after her mother died. At the time of the 1871 census Henry and Ellen and one live-in servant were established at their first house, their first ‘Westcott’, in Keswick Road, Putney. They were a devoted couple, despite superficial differences. Ellen was a staunch Conservative, while Henry was a Liberal who made no secret of his ‘radical’ Gladstonian principles. Ellen, treating political differences as matters never to be aired in public, carefully stifled discussion of politics in her home.

Both were traditional Protestant Christians, philanthropists with a strong sense of duty and public service. Henry’s politics aside, they were a typical middle-class Victorian couple and, as their family grew, a prosperous professional family. By the time of the April 1881 census, Henry and Ellen, six children and three servants lived at ‘Westcott’ in Portinscale Road, literally around the corner from their first house. From here, for thirty-seven years until he died in 1908, Henry would walk to the station, attired in his top hat and frock coat, sometimes accompanied part of the way by Clement, and take the 9.00 train to his office. The family never owned a carriage; if rain or snow prevented walking he would take a hansom cab.

Ellen ran the house, applying discipline and structure but without tyranny. She instilled in all her children the idea of the family as the most important element of life, an organism that supplied all its members’ needs. Modern notions of ‘unique identity’ were unknown. As Attlee recalls, ‘We were not encouraged to have a good conceit of ourselves.’4 The ambition of the older boys was to become like their father, while the younger boys wanted to become their elder brothers.5

Physically, Clement was the baby. Slight of stature, he lacked the physique of his elder brothers – and of his younger brother Laurence, twenty-two months his junior, who soon overtook him in height. It was a source of amusement that, unlike other families where a younger brother wore the hand-me-down clothes of elder brothers, Clem would inherit clothes as Laurence grew out of them. His slight figure concealed a wiry toughness, but was a source of concern to Ellen, who kept him at home in his early years, unlike his older brothers, who went to school in Putney.

Until he was nine, Clement lived among women: his mother, his sisters who were schooled at home, their governesses, and his four unmarried aunts, two miles away in Wandsworth. Ellen took charge of his education, supplemented in time by a French governess who instilled a good French accent. This, Clement recalled in his autobiography, ‘with other nonsense was speedily knocked out of me when I went to school’.6

When his brothers were at home there were endless games but, alone for long periods, Clement combed the shelves of his father’s library, reading indiscriminately. He acquired an early love for poetry, venerated Alfred Tennyson, and memorised lengthy passages. His brother Laurence recalled that his memory and ability to absorb everything he read was his most impressive skill.

Among Clement’s early memories were Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee of 1887, when the family decorated the house with bunting,7 and the annual Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race. It is a half-mile walk from Portinscale Road to Putney Bridge, the start of the Boat Race course, and Clement recalls that ‘Any visitor to our house was at once asked, “Are you Oxford or Cambridge?” Our general view was that the Universities existed solely for the purpose of this race.’ The Cambridge crew used to stay in the house next door to the Attlees and Clement ‘always hoped that one day the crews would meet in the street, when, if they followed our example, there would be a fight’.8

Every summer Ellen and the children spent a month by the sea, where Henry joined them for two weeks. Clement’s earliest memory of summer holidays was of Lowestoft when he was two. In later years the family went to Seaton in Devon, which became an idyll for him. When he visited Normandy after D-Day, he wrote to his elder brother Tom that it was very like Devon.9 In 1945, when he attended the first meeting of the United Nations in San Francisco, he bestowed the highest praise on the California countryside, writing that it too reminded him of Devon.10 In 1896, at a cost of £2,000, Henry bought Comarques, a red-brick house with 200 acres of land and several cottages in the village of Thorpe-le-Soken, close to the Essex coast.11 From then on, Easter and summer holidays were spent there.

Although sparse in the finished account of his life, Attlee punctiliously recorded events in obsessive detail. These notes constitute a remarkable collection of his memories. Remarkable, that is, in what he chose to record, rather than as a coherent version of childhood and adolescence. He wrote, wistfully and nostalgically, then halted and made a list of something or other. Lists punctuate the record. Lists of boys at Haileybury and what they had achieved since. Lists of speeches that he made in the House of Commons, showing the length of each speech and the number of columns taken up in Hansard. For no apparent reason, he once made a list of the boys who had been contemporaries at Northaw Preparatory School.12

It is as though Attlee were trying to discover where he had found direction, writing an objective but uncertain biography of a different person, striving to grasp the secret of that person’s success. The practical and pragmatic politician looks back at the callow youth and barely recognises him. He is objective about that person, as if he existed in another era, on the other side of some great divide. Then, when he became too wistful, recording in detail family outings, details of school or conversations with fellow officers, he would put an end to the memories and demonstrate his need for facts by constructing another list.

Perhaps most remarkable is the catalogue of summer holidays gone by, presented in painstaking detail. Where the family went, what they did, where they stayed, whom they met, how the brothers would amuse themselves, playing cricket or bicycle polo – all are meticulously recorded as if the events were recent, so fresh are they in the writer’s mind. While the memories are eclectic, almost random, a framework of Attlee’s early life emerges. There was the structured home life – weekday routine, Sunday worship, family visits and summer holidays – that lasted for as long as he lived at home; on these are superimposed clearly defined moments when his life changed, definitive points at which he made a decision that altered his conduct, his philosophy and, ultimately, his entire life.

That ‘other person’, the pre-socialist Attlee, did exist in another era: the Victorian age. Whereas Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, which occurred when he was four, was ‘his’ Jubilee, her Diamond Jubilee in 1897 was ‘Laurence’s’. He writes of Victorian London as a civilisation vanished forever. Curiously romantic about the city in the 1890s, he recalls the smell of horse manure in the streets when transportation was horse-drawn, the Stygian gloom of the Underground where thin shafts of light penetrated the smoke-filled tunnels, the hansom cabs of the affluent, ‘the gondolas of London’. This is more than a paean to a lost innocence; the descriptions form the background to his later renunciation of the comfort of those years. He could be nostalgic for the nineteenth century while being totally objective about what was morally amiss. There was a fundamental distinction between public amenities and private living conditions. Later, as Alderman and the first Labour Mayor of Stepney, he was relentless in enforcing improvements. He was equivocal about change but single-minded in his determination to reform.

Clement was nine and a half years old when he followed Tom to preparatory school at Northaw Place, near Potters Bar. He was shy, tending to blush easily. He also had a fierce temper which Ellen taught him to restrain; this he inherited from his father, who strove to suppress any outburst. The image that Clement later developed of a placid politician, calm and ostensibly unflappable, owes more to self-control than to any natural equanimity. In his papers from his time as Deputy Prime Minister and Prime Minister one stumbles on examples of his rage, expressed in blunt responses scrawled on documents, subsequently toned down to more diplomatic language for distribution. In 1892, Henry thought Clement should learn to cope with his shyness and tendency to rage. Boarding school, that great leveller and stiffener of upper lips, was the solution.

The headmaster at Northaw, the Reverend F. J. Hall, was a long-standing friend of Henry’s, a mathematician who had taught at Haileybury and persuaded him to join the Board of Governors of Haileybury College. Hall is remembered in Haileybury College, Past and Present as a master ‘whose own skill in cricket and football was always at the service of the School, who has sent us many good players of his training since he left’.

That sentence merely touches the surface of Hall’s greatest love. He and his assistant master, the Reverend F. Poland, were passionate cricket lovers. Cricket was the dominant priority at Northaw; religious knowledge, the only subject deemed worthy of intellectual enquiry, came a poor second. Clement later described the school’s function: ‘As a nursery for producing gentlemanly professional cricketers,’ he wrote, ‘the school could hardly have been bettered.’13 While he was never an outstanding cricketer (‘a good field, nothing of a bowler and a most uncertain bat’),14 he did distinguish himself in religious knowledge, winning the Bishop’s prize.15

Despite his lack of success on the field, he remained throughout his life an avid follower of the game, an ardent reader of Wisden,16 able to recite batting and bowling averages of leading cricketers. Labour Members of Parliament, when conversation was desultory, would draw him out by referring to the progress of a county match, a technique that would make the taciturn leader positively garrulous. When he flew to Washington for meetings with President Truman in 1945, he took Wisden to read on the plane.17 When, in Luddite-like fury, he objected to having a ticker tape at 10 Downing Street, he was persuaded of its value when his press officer Francis Williams pointed out that it would bring him up-to-date scores of cricket matches. For ever thereafter he referred to it as ‘my cricket machine’.

Clement’s memories of Northaw, while objective and realistic about its eccentric teaching methods, are entirely pleasurable. Although he doubted the value of the teaching – with reason, as his sketchy knowledge of Latin and Greek was to impede his academic progress at public school – fifty years later he had only fond recollections of forty youngsters gambolling about the school grounds.

Among Clement’s contemporaries were two future ministers. One future colleague was William Jowitt, four years younger than Clem, who was put in his care when he came to the school. Jowitt was elected to Parliament as a Liberal in 1922. He later joined the Labour Party and served as Lord Chancellor throughout the two post-war governments. Another future Labour minister was Hilton Young, head boy when Clem entered the school. On one occasion, Young, observing him at tea, staring disconsolately at his meagre ration of bread and butter, promptly fetched his own jar of jam and let Clement help himself, a remarkable breach of stratified school etiquette. Young was later Minister of Health in Ramsay MacDonald’s government and was created Baron Kennet in July 1935; Attlee recalled that when he was in the government, he was able to do Kennet some slight service. The latter, remembering the incident, wrote to him, ‘It seems that if you cast your jam upon the water, it will, like bread, come back to you after many days.’18

Aged thirteen, having received the scantest of education at his preparatory school and spectacularly ill equipped academically, Clement went to nearby Haileybury to sit the entrance examination in the spring term of 1896. He passed and followed in the footsteps of his three older brothers.

Haileybury is a handsome school. Approached by a long drive, the school buildings are grouped around the main quadrangle. The arrangement of buildings is not only aesthetically pleasing, it is also practical; the different ‘houses’ are less physical buildings than administrative units. In many public schools, houses are scattered over a large area, while at Haileybury, boys from different houses shared the same living space. Four boys from different houses often shared a study; all boys, except those in one remote house, ate all their meals together. This was important to Clement, who felt that he had a wider acquaintance than boys at other public schools.

Few contemporaries would have picked out the young Attlee as a future Prime Minister. He spent four years in the middle of his class, never identified as a candidate for a scholarship to Oxford or Cambridge. Sports counted for much, and it was generally from the ranks of athletes that the college’s prefects were chosen. Here, too, Clement was of only average ability. He stepped in occasionally as a second-rank player in the house rugby team but never with regularity. He was outstripped by Laurence, who arrived a year later and became a fixture in the Lawrence House cricket and rugby teams. A talented cricketer, he displayed the one skill that Clem would dearly have loved to possess.

The headmaster, Canon Edward Lyttleton, was, in Clement’s view, ‘a great man in his way … a hopeless headmaster’. To junior boys he was a remote figure; when they reached the sixth form they came more into contact with him. Clem, therefore, would not have known him well until his last year. They did, however, have close contact in March 1900, when Ladysmith was relieved by British forces in the Second Boer War.

The war had erupted in October 1899 and by the end of the month the Boers had encircled General White and 8,000 men at Ladysmith. The siege lasted for four months. When the siege was lifted, the Haileybury boys, amid the national rejoicing, expected Lyttleton to grant a half-holiday, normal procedure on such an occasion. Lyttleton, an anti-imperialist with pro-Boer sympathies, refused to do so. The majority of boys decided to cut school and stage a march through Hertford in defiance of the headmaster, who, predictably, regarded this as a flagrant breach of discipline. He reached a curious decision. The prefects were too senior to be beaten and the juniors too young, so the boys of the upper school ‘expiated the sins of the rest’.19 That evening Lyttleton caned seventy-two boys of the upper school, including Clement. Fortunately, Clement recorded, ‘the Canon was tiring when he got to me’. This was just as well, as ‘he had a lovely wrist’.

Clement had more contact with his housemaster Frederick Headley, a natural scientist. Eight years after Clem left Haileybury, Headley published his anti-socialist diatribe, Darwinism and Modern Socialism. The principal theme of the book is a defence of capitalism, specifically of the ingenuity of capitalists large and small, concluding that socialism would never take root in Britain. Capitalism, particularly monopolies or trusts, is not without its faults, Headley admitted. On the other hand, socialism would inevitably have a ‘crushing, deadening influence’ and would ‘introduce unjust and impossible economics’. It would, Headley maintained, ‘destroy the main motives for enterprise and put an end to the struggle for existence, the action of which maintains the health and vigour of human communities’.20

It is a beautiful irony that the man most responsible in loco parentis for Clement’s moral education in his teens should be convinced that there was no future for socialism in Britain. It is equally ironic that Clement, an instinctive, unquestioning Conservative during those years, would certainly have agreed with him.

In one sphere of school life he did ask questions, however. He had been brought up in a family where religion was an essential part of the fabric. His mother held daily readings of the Bible in which all the children still at home participated. On Sunday evenings in Putney he allowed his mind to drift during evening service, setting himself puzzles to solve while the service ground on. At Northaw he was taught by two Protestant ministers and, now at Haileybury, the ineluctable Christian education led to his confirmation into the Protestant Church. Although he had begun to reject the ‘mumbo jumbo’ of religion, he kept his doubts to himself. It would have wounded his mother deeply if he had refused to be confirmed; the tactful course of action was to let the system absorb him as every Protestant public school absorbed its charges. He believed in Christian values, but not in the ceremony of it all. It could do no harm to proceed. To resist would cause damage.

Throughout his life he was at ease with men of the cloth and he never quarrelled with Tom, a thoughtful, committed Christian.21 Once Clem adopted socialism, he saw its aims as substantially the same as those of Christianity – indeed, of most religions. In the climate of the late Victorian age, however, it was politic to mask his doubts with apparent conformity.

In September 1900, at the beginning of his last year at Haileybury, Clem was elected to the College Literary Society, joining the intellectual leaders of the school. He also belonged to the Shakespeare Society and the Antiquarian Society. Although never a leading actor, he performed in several school productions of Shakespeare during his last three years.

The Literary Society met on Monday evenings to debate typical issues of the day: free trade, whether the female sex encroached on men’s rights, whether old school customs were dying out and should be revived – the standard fare of school debating societies. Clement was a platform speaker on two occasions, in each of which his Conservatism was given full rein.

On the first motion Clement opposed the motion ‘that museums and picture galleries should be open on Sundays’. The record of the debate in The Haileyburian, the college magazine, reported the thread of his argument. What class, Attlee asked, would benefit from the opening of museums and galleries? Certainly not the poorer class, as they could not appreciate them. He thought that it would be giving the upper class another excuse for not going to church. It was introducing the thin end of the wedge.22

When Clement recalls that he was a Conservative in his early years, he understates the extent of that position. He must have blushed, as a socialist convert, to recall the vapid arrogance of his teenage views.

Three weeks later he opposed the motion ‘that Members of Parliament should receive pay’. On this occasion he was on the winning side.23 In this debate too his position was solidly reactionary; there is no political similarity between Clement Attlee at the age of eighteen and the young man of a mere seven years later after a spell in the East End of London.

Clem was also active in the Antiquarian Society, of which his friend Charles (‘Char’) Bailey was secretary. He was elected at the beginning of his last year and gave papers on Colchester and Saxon London, highlighting the strategic value of each.24 His principal academic interest was in history and it was to read that subject that he applied to Oxford University that year.

Haileybury had a strong military tradition and Clement joined the Officer’s Training Corps, known at the time as the ‘Haileybury College Rifle Volunteer Corps’. In this activity he won various awards and rose to be a sergeant. In the spring term of 1901 he was part of the team that won the Army Cup, awarded for drill. In the summer of 1901, the end of his last term at Haileybury, he went to military camp at Aldershot and was judged the most outstanding cadet. He enjoyed the military discipline, an essentially physical pursuit in which athletic skill counted for less than on the rugby field.25

His four years at Haileybury were overall enjoyable, although he later recalled ‘considerable periods of black misery’.26 He records that the winter term of 1899 was his worst; Char Bailey moved into another study and Clement felt friendless. He made friends at first through Tom, but in the stratified world of a public school it was difficult to mix with boys two years his senior. Equally, Laurence, almost two years his junior, was as remote as Tom within the system. Clem suffered his fair share of bullying at the hands of ‘an uncouth and brutal youth called Archer Clive’27 and he did not mix easily. The ethic of the public school was quite alien to the ethic of family that he had absorbed in Putney.

Accounts of Clement’s life traditionally treat Tom as his closest sibling, largely through the voluminous correspondence between the two. It is scarcely surprising that those letters have survived as Tom, a splendid eccentric, threw nothing away. His home at Perranarworthal housed fifty years of copies of The Times, piled high in his study and in a small annexe built for the purpose of storing his ‘things’.28 In fact, the two youngest brothers were also close and met for lunch almost weekly during the war, when Laurence was working in Whitehall.29

By the time Clem left Haileybury he had established himself as a reasonably solid and worthy individual. While no great athlete, he had played a few good rugby matches for his house. His academic performance was adequate but less impressive than that of two of his friends, Char Bailey and George Day, both of whom went up to University College, Oxford (‘Univ’) with him in October 1901.

School and home intersected little but he remained close to his family and the summer holidays spent at Comarques were integral elements of his life. Henry had changed little as his children grew up. In 1901 he maintained the same household in Portinscale Road as he had for a decade, with four live-in servants. Robert, now aged twenty-nine, still lived at home, as did Mary, Tom, Clem and Laurence. Dorothy had married Wilfrid Fletcher, a chartered accountant, and was living in Wiltshire. Henry, now turning sixty, was more likely to join his children for a game of billiards than a vigorous game of cricket, but he remained a benign and influential presence in their lives.

He also remained a Liberal, committed to Home Rule for Ireland. He had many friends and connections in the Liberal Party, one of whom was John Morley, another Liberal in the Gladstone tradition. A politician and writer, Morley served as Chief Secretary for Ireland and Secretary of State for India. He also published a biography of Oliver Cromwell in 1900 and a three-volume life of Gladstone in 1903. Morley lived nearby, between Putney and Wimbledon, and, consciously or not, had an influence on Clem, who read his biography of Cromwell more than once. During the Simon Commission’s visit to India, Clem wrote to Tom, reminding him of passages in the book and referring affectionately to ‘JM’.30

It is speculative but tempting to imagine that the young Clement saw Oliver Cromwell as a model for his own life. Certainly the first sentences of Morley’s Cromwell could have flowed from Clement’s mouth: ‘I was by birth a gentleman, living neither in any considerable height, nor yet in obscurity.’ There are other similarities in their early years: one of ten children, Cromwell too grew up surrounded by females; he was educated by a Protestant minister who believed the Pope to be the Antichrist; he was a good student but, wrote Morley, ‘there is no reason to suppose that [he] was ever the stuff of which the studious are made’. It was assumed in the family that Clement would follow his father and oldest brother Rob into the legal profession. Cromwell too had been destined for the law, a period at Lincoln’s Inn being ‘the fashion for young gentlemen of the time’.

Cromwell’s ethical stance would certainly have appealed to Clem. His view of the role of the established Church, particularly the Catholic Church, was congruent with Clem’s respect for Christian values, as distinct from what he considered the peripheral flummery of ritual. Cromwell’s brutally logical approach to the primacy of Parliament, tempered by respect for the existing social order, would have struck a chord with Clem’s selective conservatism. As to his military ability, Clem considered Cromwell simply the greatest strategist in Britain’s history.31 Whether or not Clement, seventeen years old when Morley’s book was published, cherished a secret desire to emulate the Lord Protector, the book’s subject impressed him deeply. Once Clement experienced the almost spiritual conversion to socialism, the parallels between his and Cromwell’s ethical motivation are striking.

Clem’s progression to Oxford was a natural step, another necessary stage in his journey to becoming a lawyer like Henry and Robert. There is no sense of excitement in his autobiography, no modest awe at the reputation of Oxford or of the intellectual community he was about to join. Preparatory school, public school, the University – one followed the other without causing undue excitement. In autobiographical notes he described himself as ‘very much a prig’ and ‘apt to turn to pharisaism’.32 Sadly, that description seems to have fitted him well at that stage of his life.

Some of this was echoed in his final report from his housemaster, who commended him on his ability to think about things and form opinions, but commented that ‘his chief fault is that he is very self-opinionated, so much so that he gives very scant consideration to the views of other people’. For a young man about to enter a community where the majority of his contemporaries would be self-opinionated, this was a worrying character trait.

In the Michaelmas (autumn) term of 1901, Clement went up to Oxford to read Modern History. His analysis of himself at the age of eighteen is starkly objective. A typical product of his era and class, he was, he wrote, ‘mentally very young. Better read than most especially in poetry and history.’ He knew nothing of science, little of government and political institutions ‘except from the imperialist angle’. His knowledge of social conditions was derived entirely from home not school. He was decidedly fed up with public school religion. The whole trend of his mind was ‘definitely romantic and imaginative’.33

His three elder brothers had also chosen Oxford. Robert was an undergraduate at Oriel, Bernard at Merton. Tom was already in his final year at Corpus Christi, and Clement, as a freshman, found his brother’s knowledge of Oxford ways helpful as he settled in. Char Bailey and George Day from Haileybury had also been admitted to Univ to read Modern History. Both remained friends with Clement throughout their time at Oxford, Bailey remaining in touch for much longer. The college friendship most important to Clem, however, was the immediate bond he formed with a young man who had returned from Australia and been to school at Repton before Oxford.

Hugh Linton was the second son of Sydney Linton, the first Bishop of Riverina, a new diocese in New South Wales. Born in 1882 into a family with a long Oxford tradition, Hugh was the grandson of two deans of Christ Church and was, himself, destined for a career in the Anglican Church. His father Sydney was an undergraduate at Wadham College from 1860 to 1863 and twice played for the University against Cambridge at Lords. A missionary of remarkable energy and zeal, he was appointed Anglican bishop in a diocese embracing a third of New South Wales in 1885. An indefatigable worker, he devoted himself to his mission, literally working himself into an early grave in 1894.

The young Hugh revered the memory of his father and, from the age of eleven, when his father died, nourished a desire to return to Australia and continue his work. His early years had been spent on the edge of the outback in the western part of the state and he certainly shared with Clement his memories of the huge sprawling diocese. Whether or not Clem was attracted by the ideals of missionary work, the thrill and the purpose of it remained vividly alive for Linton. After going down from Oxford, he was ordained, serving in the Southwark diocese for four years before returning to Australia to continue his father’s work in 1910.

Linton was one among many sons of churchmen at Univ in Clement’s time. Of his contemporaries, Arthur Preston from Charterhouse, reading Modern History, became Bishop Suffragan of Woolwich and Archdeacon of Lewisham; Adam Fox from Winchester College, reading ‘Greats’,34 became a Canon of Westminster Abbey. A further half-dozen of Clement’s contemporaries, younger sons of well-to-do families, became ordained ministers. The Church was a common choice of career for younger sons but, even so, there was an unusual number of future churchmen among the undergraduate body at Univ between 1901 and 1904.

The friendship between Clement and Linton remained central to both their lives in Oxford. In the tradition of the era, each acquired a nickname. Linton was ‘Loony’, while Clement rejoiced under the cognomen of ‘Monkey’. Toward the end of the Michaelmas term in their final year, in December 1903, they gave a joint coming-of-age birthday dinner. Taking a mid-point between their twenty-first birthdays, they offered their guests a spectacular seven-course meal: Sole Mornay, Chicken Vol-au-Vents with Oysters, Welsh Leg of Lamb, Golden Plover, Chicory Salad, Pastry with Sabayon Sauce, finishing with Mushrooms a la Gorgona.35

This was a departure from Clement’s normal life. He was not an extravagant undergraduate. Nor did he wear a hairshirt, for he had an adequate allowance of £200 from his father. After a year ‘living out’, when he shared lodgings adjacent to Univ with Bailey and Day, he moved into college. He lived decently but not excessively. His rooms overlooking the High Street were among the more expensive in college at five guineas a term (the most expensive cost six guineas) and his expenditure on other items – coal, candles, dinners and buttery bill – was about the average among his peers. In the matter of personal hygiene he appears to have been more punctilious than his contemporaries; his bill for the laundress was above average.36 During the 1930s, Attlee, ever watchful of his pennies, calculated that his time at Oxford had cost £637 for the three years. Meticulous accounting itemised expenditure of nearly twenty pounds on clothes in his first year, an extravagance that was not repeated. Unlike most undergraduates, he carefully balanced his books, emerging with a surplus of £43.37

By the late 1890s Univ had developed a reputation for being ‘a particularly friendly college; we all seemed to know each other, regardless of background, wealth (or lack of it), and academic or athletic ability’.38 Clement was captivated by Oxford, and by Univ, the oldest college. It was, above all, a friendly college with a mix of athletes and intellectuals and – important after Haileybury – ‘a lack of cliques’.39 ‘We do not seem to have produced scholars of distinction just then, or lawyers,’ one old member reminisced, ‘but prided ourselves on attracting men of general ability and varied interests which I still think is the best aim of a College.’40

This esprit de corps, the unwritten code of being a ‘Univ man’, involved taking more than a passing interest in sports, especially rowing, and participating in the various activities that collectively represented ‘college life’. This embraced a balance between mens sana and corpore sano. Mornings were devoted to academic work, afternoons to physical activity, Sundays to God. Clement fitted easily into this routine, not least because it was a fair replica of his life in Putney.

The wages of deviation were potentially serious. Lewis Farnell, a Fellow during Clem’s time, wrote of the public school influence that it demanded uniformity and was intolerant of aberration from the norm. Eccentric behaviour varied from harmless chaff to ‘something much graver’.41 Fred Bickerton, head porter at Univ, recorded with apparent unconcern the fate of one undergraduate who refused to be a ‘Univ man’. One night, when Bickerton was on duty in the lodge, the undergraduate rushed in, naked, tarred and feathered, ‘like a chicken in a nightmare. He was gibbering with terror, shaking and shivering all over, and in hysterics. His room had been upended, pictures and furniture thrown into the quadrangle.’42

Undergraduates were expected to make their friends principally among other members of their college and ‘outside’ friendships were regarded as undesirable. For Clement, however, there was an important influence on his undergraduate career in the person of his older brother. Through him, Clement became friendly with a group of young intellectuals at Corpus Christi College.

Tom Attlee and Edric Millar went up to Corpus Christi College in 1899. Millar was the more accomplished academically – he won an Exhibition (a minor scholarship) and took a First in both Honour Moderations and Greats. Active in the literary and intellectual life of the college, he was something of a mentor for Tom and, through him, for Clem.

Corpus Christi had two essay clubs, the Tenterden Essay Club and the Pelican, at which members read papers on principally literary topics. Millar belonged to both, reading papers on George Sand and Gustavus Adolphus to the Tenterden and on Matthew Arnold to the Pelican. He was subsequently elected president of both clubs.43

When Clem arrived in Oxford in 1901, therefore, Millar was an established figure at Corpus Christi and Tom decided that he should give his brother advice on how to deport himself in Univ. Millar, the oldest of eleven children, was quite accustomed to bossing six younger brothers about and he happily accepted Tom’s suggestion.44 Clem became friendly with Millar45 and, on his advice, became ‘someone in college’ using the ladder of the University College literary clubs, the Martlets and the Churchwardens.

Members of the Martlets were a self-consciously intellectual group, brimming with undergraduate pretentiousness, but ultimately serious. Their minute book opens with the grandiose statement that: ‘The Martlets Society dates from dim antiquity but after a temporary disappearance, it was constituted in its present form on May 8th