4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

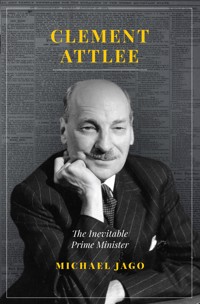

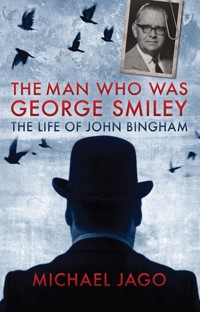

Investigator, interrogator, intellectual hero: the perfect inspiration for the perfect spy. This first full-length biography traces the life of the remarkable and engaging John Bingham, the man behind John le Carré's George Smiley. The heir to an Irish barony and a spirited young journalist, John Bingham joined MI5 in 1940; his quiet intellect, wry wit and knack for observation made him a natural. He took part in many of MI5's greatest wartime missions - from the tracking of Nazi agents in Britain to Operation double cross that ensured the success of D-Day - and later spent three decades running agents in Britain against the Communist target. Among his colleagues his skills were legendary and he soon became a mentor to many a novice spy - including one David Cornwell, the later le Carré. Bingham, too, was an innovative writer who perfected the psychological thriller, marrying cold objectivity with an explanation of the darkest reaches of human behaviour. His early novels were applauded but, for all his success, Bingham struggled to match the fame of the man he had inspired. Drawing on Bingham's published and unpublished writings, as well as interviews with his family, Michael Jago skilfully tells the riveting yet poignant tale of the man who was George Smiley.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 478

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title Page

Acknowledgements

Preface

Chapter 1 Ancestry, 1100–1908, and Early Life, 1908–27

Chapter 2 Political Awakening, 1927–9

Chapter 3 Journalism and Marriage, 1929–39

Chapter 4 Fighting Fascism: MI5, 1940–45

Chapter 5 Allied Control Council, 1946–8

Chapter 6 Journalist, 1948–50

Chapter 7 Return to MI5 and Debut as a Novelist, 1950–58

Chapter 8 The Genesis of George Smiley, 1958–66

Chapter 9 MI5 Agent Runner and Novelist, 1960–69

Chapter 10 Disappointments, 1969–79

Chapter 11 Smiley Triumphant, 1974–82

Chapter 12 Retirement, 1979–88

Chapter 13 The Seventh Lord Clanmorris, 1908–88

Bibliography

Index

Plates

Picture credits

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to everyone who helped me assemble this biography of John Bingham, 7th Baron Clanmorris of Newbrook. In truth, it was a pleasant task as no one had anything but good to say about him. Above all, the assistance given to me by his children, Simon, the 8th Baron Clanmorris, and the Hon. Charlotte Mary Thérèse Bingham, has been invaluable. Together with Gizella, Lady Clanmorris, and Charlotte Bingham’s husband, Terence Brady, they provided me with a framework and were assiduous in spotting errors of emphasis and fact throughout the process.

Of John Bingham’s friends and colleagues, I was helped greatly by his goddaughter Rosy Burke (née Denaro), Livia Gollancz, Maureen Johnston and the late Arthur Spencer. Their reminiscences and insights gave me an understanding of a multifaceted man.

In my researches I must single out Chara Connell of Orion Publishing who rashly offered to commandeer the photocopier to reproduce documents from the Orion archive. At Boston University, Adam Dixon tirelessly wheeled boxes of documents lodged in the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center. At Cheltenham College, Jill Barlow was an accomplished sleuth in helping me identify the schoolmaster Ackersley from John Bingham’s first novel. And I am delighted that the daily sifting through 1930s and 1940s issues of the Hull Daily Mail and the SundayDispatch did not prevent my indefatigable research assistant Tess Harris from earning her first-class degree.

Several people contributed valuable comments after reading the manuscript. Of these I am particularly grateful to Frances Burton, Janey Burton, Captain Seth Johnston (US Army), Chris and Frances Pye and Adam Sisman, biographer of David Cornwell, as well as my son and daughter-in-law James and Dr Elizabeth Jago. The latter helped further in explaining the nature of a specific phobia, an ailment that John Bingham suffered from. Further medical information concerning transient ischaemic attacks was supplied by Juliet Jamieson. Alysoun Sanders at Macmillan opened her archive and facilitated my research. For their help in recreating the young John Bingham through the eyes of their father Jacques de Moncuit de Boiscuillé I am indebted to Hervé and Geoffroy de Moncuit in the village of Tigy in the Sologne. Their mother, ‘Mami’, also helped with her memories of political discussions in pre-war France.

For constant encouragement I am indebted to my agent Andrew Lownie. At Biteback Publishing, Mick Smith’s laconic comments and more expansive advice from my editor Hollie Teague have transformed the writing of my first book from a mere task to an exciting project.

The customary formality is to thank one’s wife for her support. My wife Carol has lived with this project for almost two years and has unstintingly contributed her editorial skill and calm wisdom – so this expression of gratitude is greatly more than a formality.

PREFACE

It was mid-afternoon before the agent was able to leave London. There had been a panic about two spies who, the Abwehr suspected, had been ‘turned’ by MI5, the British Security Service. Since the cancellation of Operation sea lion and, more markedly, since the launching of BARBAROSSA, the invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June, the infiltration of German spies into Britain had slowed to a trickle. Moreover, the flow of refugees from western Europe had eased after the panic-filled days of July and August 1940, and MI5 was now able to free resources and focus more on weeding out German agents already in Britain. When the invasion scare had been at its height after the fall of France in 1940 and the sheer volume of refugees from France, Belgium and the Netherlands had occupied all the British interrogators at the reception centres, Abwehr agents had been able to move about Britain more easily. All that had changed by November 1941.

The agent shivered and pulled his travelling rug around him. This month had brought the worst weather since the winter of 1843 and, as he headed north on the A5, his thoughts turned to the soldiers in the army group centre engaged in the Battle of Moscow, which had started a week before. Over there the temperature was minus 12 centigrade and the 3rd Panzer Group was lurching east towards the Moscow Canal, hampered by a supply crisis that had slowed it down since October. However cold it was in England, it was nothing compared with what the Wehrmacht was being subjected to on the Eastern Front.

Finally, he was out of London’s northern suburbs with a clear road ahead. As he passed the road to Coventry, he cast his mind back a year almost to the day, to 14 November 1940, the night that 515 bombers of Luftflotte3 had carried out Operation MONDSCHEINSONATE and smashed one of the principal manufacturing centres of the British war effort. A new word, coventriert, had entered the German language after that raid. Reichsminister Goebbels now talked of cities being ‘coventried’. That was a night that the British would take a long time to forget.

He was a natural agent, thirty-three years old, unglamorous, stocky, slightly above average height, taciturn, a patient listener. He spoke fluent English as well as German with a compelling, mellifluous voice, and had that ability all the best agents have: to efface himself, to vanish into a crowd. People thought of spies as being exotic, demonstrative, he reflected, while he was the opposite. Mild, almost shy, he took pride in being a forgettable man, someone who could pass unnoticed among his fellows.

He would need to be unnoticed tonight, he thought, if he was to get what he wanted. His appointment outside Stafford was at 7:30 p.m. and he needed to park his car in the outskirts of the town and walk a mile and a half through the early snow, anonymous, unremarkable, to meet Irma Stapleton when she left the factory. He checked his watch. More than halfway to Stafford with two hours before he met her. If the snow didn’t get worse, he was in good time.

He thought ahead to the meeting. If Stapleton was telling the truth – which he knew was a rare commodity in his world – she would bring him a 22-millimetre Oerlikon shell, which the factory was manufacturing. He had also sent a secure message to her to bring the details of the location of the Royal Ordnance factory and of the several factories around Stafford owned by Wade’s Chain Garages, together with their production figures, if possible. If he succeeded in getting hold of these, he reckoned, the drive from London would have been worthwhile.

He was in Stafford by 6:30 and the streets were quiet in the blackout. The shift changed at the factory at 7:00 that Wednesday night and Stapleton had a ten-minute walk to their rendezvous. Stepping out briskly, he was at the meeting point by 7:25.

When Stapleton arrived, she looked about her cautiously before digging in the bag she carried. She had brought everything he had asked for: a map with the location of every Wade plant, their production figures and, as she had promised, an Oerlikon 22-millimetre shell, as well as a two-pound anti-aircraft shell igniter and a 22-millimetre shell base plug.

As Irma Stapleton handed them over to the agent, three burly men appeared from the shadows and handcuffed her. The agent turned to flee but he too was almost effortlessly overpowered and handcuffed. The men identified themselves as officers of the Special Branch of the Metropolitan Police.

Screaming that she was a loyal British subject who had been approached by German Intelligence, Stapleton pointed at the agent and denounced him. She had gone along with the meeting, she protested, only in order to hand him over to the police as soon as she had the chance. She was innocent; the agent had come from the Abwehr, from the Gestapo. She knew her duty and she was going to denounce him as soon as she could, but the Special Branch men had arrived before she could do so.

She demanded to be allowed to make a statement. She would go with the officers to the nearest police station and clear up this ridiculous misunderstanding. The agent was the spy, she shouted, not her. Still screaming, she was bundled into a police car and driven away.

One officer stayed behind to guard the handcuffed but unflustered agent. Turning the key to remove the handcuffs, he looked into the face of his prisoner for the first time and smiled.

‘Can I give you a lift to your car, Major Bingham?’

CHAPTER 1

ANCESTRY, 1100–1908, AND EARLY LIFE, 1908–27

For my forwardness in her Majesties servis, for other faulte, he could not finde in mee, nor ever shall.

Sir Richard Bingham to Sir Francis Walsingham, 12 November 1580

By the twelfth century the de Bingham family was established at Sutton Bingham, a few miles south of Yeovil in Somerset. The first notable Bingham was Robert, brother of Sir Ralph de Bingham, squire of Sutton in the reign of Edward III. Robert was born in 1164 and in 1229 was consecrated Bishop of Salisbury. Succeeding Bishop Poore, who had begun the building of the cathedral in 1220, Bishop de Bingham took charge of the construction, which was completed in a mere thirty-eight years. His legacy to Britain is the uniquely homogeneous church, entirely built in Early English Gothic.

His nephew, second son of Sir Ralph, married into the Turberville family, they of Thomas Hardy’s novel Tess of the d’Urbervilles, and acquired the manor house in the village of Melcombe, known today as Melcombe Bingham. For three centuries the family remained obscure country squires between Dorchester and Blandford Forum until the rise to prominence of Richard Bingham, an ambitious third son. Leaving Dorset for a military career, he succeeded in making powerful enemies but also in gaining the favour of Queen Elizabeth I, who commissioned him admiral, knighted him and appointed him Governor of Connacht.

A bloodthirsty man who shot or hanged 1,100 shipwrecked survivors of the Spanish Armada – excepting those who might bring a tidy ransom – he laid the foundations of his family’s fortune by the simple expedient of appropriating the land of the Irish rebels he suppressed. At the end of a controversial career, Sir Richard bequeathed at his death in 1599 a substantial legacy to his brother George, the Governor of Sligo. A grateful Queen Elizabeth had a memorial plaque erected in his honour in Westminster Abbey.

Thus was founded an Anglo-Irish dynasty that produced the two most famous branches of the Bingham family. Henry, the elder son of the governor, was created the 1st baronet; his great-great-grandson Charles, the 7th baronet, was created Baron Lucan of Castlebar in the County of Mayo in 1776 and was further promoted to Earl of Lucan in 1795. The younger son, John, fathered the line that, five generations later, produced John Bingham, ennobled as the 1st Baron Clanmorris in 1800.

John Bingham controlled two seats in the Irish Parliament – Newbrook in County Mayo and Fortfield in County Dublin. Delivering these two votes in favour of the Act of Union between England and Ireland, he received from a grateful sovereign a cash sum of £8,000 and a barony, together with a bonus of £20,000 in order to live in the style befitting an English nobleman. Assuming the Scottish-sounding title of Lord Clanmorris of Newbrook (as a Scottish peerage carried more prestige than an Irish one) and adding to his coffers the equivalent of £3,000,000 in today’s money, the 1st Baron, with substantial estates in Galway and Mayo, could be well pleased with the Act of Union.

His daughter, the Hon. Maria Letitia Bingham, married Robert ffrench in 1815. The ffrenches, an established Anglo-Irish family, had fallen on hard times, and Robert’s estates were encumbered with debt. In 1829 ffrench borrowed £25,000 – £10,000 for his own use and £15,000 for that of his sisters – by mortgaging his estates to the 2nd Lord Clanmorris. The value of that loan in today’s money is in excess of £2.5 million – a not insubstantial amount to lend to a brother-in-law.

The source of such wealth was land, enormous tracts of it. The will of Henry Bingham, who died in 1789, reads like a gazetteer of western Ireland as he lists his properties in County Mayo. In 1805, according to a letter from the 1st Baron to Lord Hardwicke, the rent roll produced an annual income of £12,000, the equivalent of £1.2 million today.

Unlike many Anglo-Irish landlords, the Binghams were thought benevolent. During the nineteenth century the downtrodden indigenous Catholic Irish saw their hopes for expansion of the Irish economy consistently dashed; resentment of all English landlords, benevolent or exploitative, absent or present, spread across the west and south-west of the country. Yet the Binghams survived and even flaunted their wealth. Prodigious feats on horseback, possession of ‘the best stud of hunters and steeplechasers that Ireland contained’, travels to and fro with a stable of racehorses – these diversions occupied the Binghams while their livelihood was threatened by the spectre of renewed Irish uprisings.

In an accidental fire in October 1837 the family seat at Newbrook burned to the ground; buckets of water passed hand-to-hand failed to stop the eight-day blaze. The elegant, spacious square house became another Anglo-Irish ruin, never to be rebuilt.

Eight years later, when blight destroyed the potato crop in the summer of 1845, predictable tragedy followed. The famine, followed by widespread disease, brought mass emigration. A financial crisis in 1847 reduced any wish the English government might have had to provide effective relief for Ireland. Conditions in the west of the country, where the Clanmorris estates lay, were especially dire; the population of Connacht fell by 30 per cent in the 1840s.

In 1847 John Charles Robert Bingham succeeded to the title as the 4th Baron. Two years later he married Sarah Persse, member of a family that periodically intermarried with the Clanmorrises. Their union was blessed and, after two daughters, John George Barry Bingham was born on 27 August 1852. In the same year, Sarah’s brother Burton Persse became master of Ireland’s most famous hunt, the Galway Blazers, a position he would hold until his death thirty-three years later. Rebellion might be gaining momentum in Ireland, but the Anglo-Irish aristocracy in Galway continued to hunt, to send their children to Eton and to intermarry.

When crops failed in successive years from 1844 to 1847, the value of Irish land plummeted and, once again, the counties to the west – Galway and Mayo above all – were most affected. Even the most compassionate landlord lived in fear of financial ruin and agrarian rebellion. Emigration was the solution for many: suddenly landlords, having evicted their poorer tenants, began to lose their good ones too. With huge swathes of Galway still uncultivated, the fragile landlord–tenant contract simply evaporated.

The famine fuelled the Fenian movement, which demanded Irish freedom from British rule. As the first Fenian uprising was suppressed and its leaders executed in 1867, John George Barry Bingham completed his education at Eton and began his military service. By that time, the rent roll enjoyed by the 1st Baron had shrunk and the family strove to perpetuate its pleasures from the residual income. ‘Hard-drinking and hard-riding’, they continued the life of opulent squires, maintained their stables, their hounds, their fishing lodges. The future 5th Baron, moreover, had formed a close friendship with Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught, and such royal friendships rarely come at little cost. By 1878, not to put too fine a point on it, the barony was on the financial rocks.

But it remained a barony, a highly marketable asset. On 27 June 1878, having succeeded to the title two years before, the 5th Baron bestowed on Matilda Catherine Maude Ward the title of Lady Clanmorris. Possessed of a substantial fortune and the impressive Bangor Castle, she lacked only a title. This the 5th Baron, though now bereft of other assets, could provide. The young couple were married in Bangor before 120 family members and friends. Fine presents arrived from England – a gold bracelet, set with pearls and diamonds; antique silver; a richly encrusted Etruscan necklace. The Irish situation, however, dissuaded the English from attending in person.

It was, on the surface, a splendid match for both bride and groom. In simple terms, ‘Clan’ provided the title and Maude provided the money. Maude came from a hugely wealthy Ulster family with impeccable Protestant credentials. Clan had royal connections, Maude provided a solid base – the Victorian Bangor Castle that her father, razing the original castle to the ground, had completed in 1852.

There was harmony in the arrangement, but beneath the placid surface surged discord, philosophical and physical. Clan was ‘the typical hunting-drinking man of his day’ and hunting was supplied in the west by the Galway Blazers, of whom he was master from 1890 to 1895. This modest-sounding position was the apogee of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy. The roll of past masters of the hunt reads like a Who’s Who of the Protestant ascendancy, and the exploits of members, both on and off horseback, were exotic. The hunt, originally known as ‘The County Galway Hunt’, acquired its cognomen ‘The Blazers’ in the early 1800s after the hunt members set alight Dooley’s Hotel in Offaly during after-hunt revelry.

As for the drinking, Maude rapidly realised that Clan was happiest in the company of his hunting friends when ‘Clan’s end of the long table in the castle dining room was always loud with laughter and the glasses were always full, while Maude’s entourage found the going sticky’.

A caricature of the Anglo-Irish ascendancy, Clan enjoyed hunting or fishing. Despite the decline of his estates in the west, he had hung onto some good salmon and trout fishing and a handful of lodges. He took Maude out with the Blazers, but her outings ceased in mid-season when she became pregnant for the first time. On 22 June 1879 she presented Clan with a son and heir, Arthur Maurice Robert, named after Arthur, Duke of Connaught but always called ‘Maurice’.

After Maurice’s birth, Maude remained almost permanently in a state of pregnancy for nine years. Maurice was followed by John Denis Yelverton (1880), Edward Barry Stewart (1881), Harriette Ierne Maude (1882), Emily Ina Florence (1884), Hugh Terence de Burgh (1885) and Henry Derek Thomas (1887). A brief pause ensued before the births of Eleanor Clare Alice (1892), George Roderick Bentinck (1894) and Richard Gerald Ava (1896).

This would have made for a picture-perfect Victorian family but for certain obstacles. Paramount were Maude’s intense dislike of pregnancy and lack of interest in her children; secondly, Clan was by then making substantial inroads on her fortune, inroads impeded only by the Married Women’s Property Act of 1882, protecting a woman’s rights over her property when she married; thirdly, Clan began to make regular trips to Paris, ostensibly to have his adored brown poodle clipped but really, the family suspected, in order to enjoy the more celebrated attractions of that permissive city.

Maurice followed his father to Eton and was twenty when the Boer crisis erupted in South Africa. War was declared on 11 October 1899; Maurice joined the 5th Royal Irish Lancers on the following day and shipped out to the Cape.

They were soon engaged. Heading north under General Buller to relieve the British garrison of Ladysmith, they fought at the Battle of Colenso on 15 December. This was a bloody affair, fought all day in blistering sunshine. The cavalry, although tactically of little value, were fortunate to be mobile as the relentless slaughter unfolded around them. Maurice wrote to Clan in jovial spirit: ‘Dear Father, I have had some pretty good experiences the last few days. I got my baptism of fire last Friday at the battle of Colenso.’ Only later did he admit that he was ‘nearly done for at Colenso’; in the ethic of his class and era, modesty had forbidden that he mention it at the time.

During the first half of 1900 the war dragged on inconclusively. The Battle of Belfast, the last important set piece of the war, ended on 27 August 1900. When it became clear that no peace could be negotiated without unacceptable concessions from the Boers, General Louis Botha’s strategy of conducting guerrilla war was adopted.

To guard against simultaneous revolt at several points in Cape Colony, Maurice’s regiment was posted to Cape Town and brought its war to a relaxed end amid Cape society. Despite its Dutch origins, Cape Town was by 1900 a very English town, its social life modelled on British lines, offering, like any colonial capital, an agreeable way of life to visiting army officers.

Rest and relaxation in Cape Town were most welcome to Maurice and his fellow officer Lieutenant George Capron. We can imagine the two handsome, dashing cavalry officers settling easily into the to and fro of society on the Cape, prominent within which were the five vivacious daughters of Gordon Cloete, a justice of the peace and lay preacher.

The Cloete family in South Africa dates back to 1652, when Jacob Cloete sailed to the Cape with Johan Anthoniszoon ‘Jan’ van Riebeeck, the founder of Cape Town and the first Dutch Commander of the Cape. To have sailed to South Africa with van Riebeeck even today carries the same prestige as having crossed to England with William the Conqueror or having arrived in the American colonies on the Mayflower, and by 1701 the family was among the principal farmers on the Cape.

Two hundred years later, Gordon Cloete lived close to the original Cloete farm, in the suburb of Rosebank, in the shadow of Table Mountain. His five daughters were stalwart members of the socially conscious life of the city. Years later, John Bingham would write of the five sisters that ‘the Cloete family created such havoc among the English officers sent to fight in the Boer War that I think they occasioned more casualties than the Boers’.

Vera, the eldest daughter, captured the heart of Colonel Ted Noding of the Royal Army Medical Corps; the younger officers, Maurice and fellow Lancer George Capron, were smitten by Leila and Effie. Renée, the youngest, dreamed of marrying an English gentleman but did not meet him on this occasion. Inez alone saw her future in South Africa.

Effie, ‘the prettiest and fluffiest’ of the five girls, accepted George Capron’s proposal and returned to England with him as a married woman. Ted Noding, too, pressed a successful suit and Vera also moved to London. Renée came to England in search of a husband; but not before England had been hurled into another war in 1914.

Which leaves us Leila, vastly attracted by the notion of becoming an English baroness but, at this stage of her life, at least, a thoroughly practical young woman. She viewed her encounter with Maurice as a temporary wartime liaison contracted after the heat of fighting. She was surprised, therefore, when Maurice, posted after the war as ADC to Lord Ranfurly, the Governor of New Zealand, chose to prolong and extend their brief friendship, urging her to marry him immediately. She stalled, saying she would accept once he was promoted to captain. When this occurred in 1906, Maurice cabled her, held her to her promise and sailed to Cape Town. The young couple were married on 5 June 1907.

This was the zenith of Maurice’s life. Heir to a substantial inheritance, he had acquitted himself well in a decent regiment, rubbed shoulders with the nomenklatura of the British Diplomatic Service, and wooed and won a vivacious member of Cape Town society. He would return to Britain, he doubtless imagined, stay in the army until he attained field rank, then resign his commission to take up a few directorships, possibly run as a Unionist Party candidate for Bangor, and spend his life between Bangor Castle and Westminster. This was his due, what he had been brought up to do.

Now he brought his new wife to the neo-Gothic battlements of Bangor Castle, its vast halls, and its rigid routine laid down by Maude, the last of the Wards, the 5th Baroness, who ran ‘her’ castle in her way. Possessed of a considerable fortune, married into a recent but respectable barony, a sharp and realistic assessor of the values, moral and financial, of her successor, she – more than Clan – was the critical arbiter of the bride that Maurice carried home from the Cape. A commission in the Cavalry, she would have agreed, is a good thing. If the wages of that commission are an ‘entanglement’, then it is better to be entangled with breeding or a substantial dowry.

Leila Cloete, for all her singular virtues, brought neither to the fortified walls of Bangor Castle. Her Dutch pedigree, stretching back to 1652, may have cut some ice in Cape Town, but a Boer heritage sat ill with the Anglo-Irish aristocracy. Allowances for foreignness needed to be made, of course, at the beginning of the twentieth century. Many English noblemen – Lord Curzon, the Duke of Roxburghe, Lord Randolph Churchill, the Duke of Marlborough, the Earl of Craven – had been so rash as to marry Americans; collectively, American heiresses brought $25 billion to rejuvenate the British ruling classes and preserve their stately homes, but approval tended to be conceded in direct proportion to the asset value of the bride.

In short, Maurice appeared to have been improvident in his choice, a characteristic that was to play its part throughout his life. Maude’s reception of the returning lovebirds was, one can be sure, correct. One can be equally sure that it was also chilling, that, to use a well-worn phrase of her era, she was not amused.

Leila, for her part, was equally unamused by the state in which she found herself. From her early acquaintance with Maude until 1941, when Leila herself finally became chatelaine, she referred to Maude as ‘The Mother’. Excited at the prospect of ennoblement, she had to suffer being married to the heir, an heir on a strict allowance doled out by the lawyers of the sitting baroness, in whose eyes, she knew, she was not at all the thing. She was a lively young woman, not without ambition. She had married a man with a future, but that future was vested in assets firmly beyond the young couple’s grasp. In the meantime, she would have to live a ‘normal’ life: she and Maurice would have to create their own income, live on it, keep house. By 1903, Bangor Castle was a relic of a past era, and Belfast society was not at all what Leila had chosen. London beckoned, full of opportunity, full of hazard. Leila saw only the former.

London society, viewed from a distance in Cape Town, was one thing; the reality of Leila’s situation, marooned in the north, was another. Her husband held a commission in the army and his regiment was based not in Belgravia but in Acomb, a village to the west of York. In Cape Town she had belonged to a leading family in a narrow world; in Yorkshire she was a mere captain’s wife in an equally narrow, equally stratified world.

Maurice’s relations with his colonel deteriorated during his time at Acomb. As he was held to a strict allowance, with the riches of Bangor Castle no more than a distant prospect, Leila can hardly have felt that her dream of taking Mayfair by storm was likely to be realised. There were other concerns, moreover, to limit her horizons. In early 1908 she became pregnant. In a difficult birth on 3 November, John Michael Ward Bingham was born. The entire experience of pregnancy and lying-in had been distasteful to Leila and she took care that the episode should not be repeated.

Maurice resigned his commission in 1909 and the family moved to London. His friend Captain George Capron had become his brother-in-law, having married Leila’s sister Effie. The two Lancers renewed their friendship and embarked on the first of Maurice’s business ventures, none of which would realise the expectations – or repay the capital – invested in them. Their plan was simple: to buy young cattle in Ireland and import them to their farm in the Home Counties where they would be fattened for market. The slump in Irish agricultural prices and increasing middle-class wealth in England gave the business a very fair chance of success. Indeed, things were progressing reasonably well when Britain was hurled into war in August 1914. The two business partners, officers on the reserve list, were promptly called up, abruptly ending their venture.

John was five years old when the war broke out. To an only child, brought up by a nanny like so many of his class, his parents were distant figures; the one was consumed with making a living outside the army, a need accentuated by the other’s obsession with society and conviction that life could not be lived without at least a brace of servants. To such a couple a young child was an encumbrance and, whenever possible, Leila shipped nanny and John off to Bangor to stay with his grandparents.

Here, too, he was left much to himself. Routine was sacrosanct at the castle; Maude applied a rigid schedule to her life, spending much of her time ‘visiting’ in Bangor, a process that involved being driven in the Daimler at a sedate 20mph to call on families around town. Clan had mellowed but, now sixty-two, had little interest in a boy from London who acquitted himself ill on horseback.

John’s memories of those early years consist mainly of the solitude of roaming the grounds of the castle, hunting vermin with his beloved catapult. Neither happy nor unhappy, he learned the discipline of ‘getting through’ and of ‘sticking it out’. Physically unimpressive, possessed of a squint caused by severe shock when his nanny burned him while changing him by the fire, he had learned to be a loner, a close observer, essentially alone.

At the front, meanwhile, Maurice, the dashing young subaltern of 1899, now a 35-year-old reservist captain, was appointed Inspector of Cavalry in 1914, an unglamorous, routine post. As a reservist, he had little status. Moreover, he had resigned his commission, according to his daughter-in-law, because he was on bad terms with his colonel. Now thirty-five, with a wife and young son, he could be forgiven for being no longer eager for death or glory.

Three of Maurice’s brothers had ‘good’ wars. John Denis Yelverton, brevet lieutenant-colonel in the 15th/19th Hussars, was twice mentioned in dispatches, won a DSO in 1918 and was decorated with the Légion d’honneur. Edward Barry Stewart joined the Royal Navy at the age of fourteen and won a Victoria Cross at the Battle of Jutland in 1916. George Roderick Bentinck fought as a captain in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. Maurice’s youngest sibling, Richard Gerald Ava, a second lieutenant in the Royal Air Force, was killed in action on 10 October 1918, a scant month before the Armistice.

Meanwhile Maurice, the heir to the barony, had little opportunity to add to the family’s accomplishments. Further humiliation followed: he was bitten by a supposedly rabid dog, sent to Paris for treatment, and shipped back to England. His father died in 1916, so the Armistice found the 6th Lord Clanmorris back in Yorkshire, commanding a prisoner-of-war camp outside Ripon.

On his father’s death, Maurice was descended on by lawyers acting for his mother in Northern Ireland. Maude, whether from prescience or the simple knowledge that her eldest son was no financial wizard, had kept his allowance at its modest pre-war level. As Madeleine Bingham puts it succinctly, ‘[Maude] had managed to save her fortune from her husband, and she was not disposed to let her heir dissipate the rest. Nor was Maurice the only one Maude might have to support: there was his wife who, imprudently, had no money either.’

Accordingly, she was quick off the mark to secure her interests when the 5th Baron died. The Irish lawyers sugar-coated their agreement with Maurice, writing that Maurice, acting ‘out of duty and filial affection’, chose to forgo his valid claim on his father’s estate, allowing Maude to retain everything. Doubtless it was an act of generosity, but the action was, one supposes, made easier for Maurice by the knowledge that, in time, it would revert to him anyway.

Towards the end of the war Renée, the youngest Cloete sister, came to England to seek a good match. It was expected that Leila, now Lady Clanmorris, would use her aristocratic contacts to achieve this.

With the assistance of the casualty lists, Renée did join the landed gentry. William, the second son of Colonel Charles France-Hayhurst, had accepted his lot as a younger son and learned the profession of estate management. When his father died in 1914 and his elder brother was killed in Flanders, he unexpectedly found himself master of Bostock Hall, a minor stately home outside Middlewich in Cheshire.

The new squire set out to find a wife and secure the succession. On meeting Renée he decided to look no further. Renée extricated herself from a liaison that promised her far less, waved a fond goodbye to her former fiancé, accepted William and moved to Bostock Hall in 1918. During the same year, she became pregnant and Leila allowed her to take John’s nanny, no longer needed now that he was at prep school, to help during her pregnancy. Tragically, Renée died in childbirth, fulfilling a premonition she had had early in her pregnancy. Her daughter survived and was named after her.

Maurice and Leila, by contrast, had no control of their putative inheritance, an asset that was gradually shrinking. The Clanmorris estates in 1876 had comprised 12,337 acres in County Mayo, 5,295 acres in County Galway and 479 acres in Galway town. By 1906 much of Clan’s land was untenanted; in March 1916, the last year of Clan’s life, the family sold 3,053 acres of the estate in County Mayo to the Congested Districts’ Board for £16,121 – marginally more than £5 an acre.

With few qualifications and no capital, Maurice discussed with Leila the option usually given to a younger son: a new life in some corner of the Empire. If they were to embark on that course, then the obvious option for the couple was to pull such strings as Leila could gather together in South Africa, the country of her birth.

From Madeleine Bingham’s enchanting pen portrait of Leila, her mother-in-law, we gain the impression of a not entirely superficial nor yet profound woman, susceptible to suggestion, ever on the lookout for an original and startlingly profitable idea, equipped with all the optimism but little of the determination required to bring a project to fruition. From her reservoir of such ideas came the notion of farming in Pondoland, where land and labour were still cheap.

Pondoland, a fertile strip on the Indian Ocean stretching from Port Elizabeth in the south to Durban in the north, had been annexed to Cape Colony in 1894. It was still a land of opportunity, open to settlement. Maurice’s brother Roderick, fifteen years his junior, had already moved to South Africa, where he owned a flower farm. Maurice and Leila too planned to farm – it was unclear exactly what they would farm, but the options were as vast as the African plains. Whatever they chose would be more exotic and more lucrative than making ends meet on a modest allowance in post-war Britain.

Accordingly Maurice, Leila and John, now aged eleven, sailed south in March 1920. The trip, Maurice and Leila decided, would be valuable for them and also good for their son. John was not happy at his prep school. Short sighted and still debilitated by his squint, he was subjected to merciless teasing and bullying from his arrival at Clifton House in Harrogate. He was stoic about it all, but the memory lingered long. As late as 1953 he was to describe with feeling his experiences at prep school in his second novel, Five Roundabouts to Heaven.

Less emphatic are his diary entries during the South African jaunt. Bored by the whole adventure and the only child among a family of Afrikaans-speaking strangers, he spent long periods alone. He was accustomed to this and, as at his grandfather’s estate around Bangor Castle, his principal enjoyment lay in hunting birds and squirrels with his catapult and befriending the chickens in the back garden at Rosebank. His diary suggests that his prep school, even with the bullying inflicted by his peers, would have been more interesting. In the event, neither the ostrich farms nor the orange groves tempted his parents to emigrate. They seem scarcely to have taken the project seriously. It was four months before they left Cape Town by train in August in search of farms. By September the family had returned to England – and John to Clifton House – taking back with them one notionally positive benefit: Maurice had tasted the possibility of working for himself and amassing his own capital. Once back in London, he would go into business. Quite what business he would choose and how, without capital, he would get started were problems he would solve when he arrived home.

The second difficulty was solved by a method familiar to many aristocrats in straitened circumstances in the 1920s. Had he not ‘done the decent thing’ in allowing Maude to retain her wealth for her lifetime? Was he not soon to inherit that fortune, rightly his according to the laws of primogeniture? Could he not borrow against that future capital and put the money to better use? Either the business venture would yield sufficient profit for him to repay the capital borrowed or, at the worst, a mere portion of his inheritance would settle his indebtedness to the bank wise and progressive enough to lend him the money.

Thus reassured, he followed many of his peers to the City of London and, in common with them, found that banks were by no means averse to making loans against future inheritance. It was all too simple: not once but several times did Maurice approach the bankers, ‘borrowing insanely’ as his granddaughter Charlotte describes it. The first tranche of £15,000 (over £500,000 at today’s value) enabled him to invest in a hardware export business; subsequent drawings gave him the wherewithal to buy the lease on a house in Montagu Square, to employ a brace of maids and a cook, and enjoy an income of a couple of thousand a year, a respectable amount at the time.

Maurice enjoyed this new opulence until the hardware business collapsed. Overnight, the family lost a considerable portion of his putative inheritance. The house in Montagu Square was sold, the servants were let go, the couple moved into a flat; according to Madeleine Bingham, even more exotic remedies were discussed: ‘It was even mooted that [Leila] should look around for a millionaire to marry. Leila, all her life, had a touching faith in the healing power of millionaires.’

Quite how Leila’s marrying a millionaire while she was married to Maurice would have been achieved, or how the arrangement would have helped Maurice, is unclear.

Maurice took a series of jobs where his title was an asset, first on the board of a film company and then selling advertising space for a regimental magazine. Withdrawn, not at all the dashing officer of the turn of the century, he nonetheless became a professional guest, making regular trips to Bangor and visiting relatives who lived in far greater style than he and Leila enjoyed. They took to spending Christmas at Bostock Hall, where Leila’s brother-in-law Billy France-Hayhurst lived in grand splendour. Leila, having failed to meet the right millionaire, took a job with Madame Luander, owner of a dress shop in Albemarle Street. Despite her declared dedication to her job, Leila’s employment did not solve the pressing need for money. Fast approaching, moreover, was the expense of public school for which fees, then as now, were considerable and, worse, ineluctably payable in advance. At all events, on 31 May 1922, John was registered to attend Cheltenham College from January 1923.

The application was made when John was already thirteen years old. Generally, English boys are ‘put down’ for their public school much earlier, often at birth. The natural deduction is that he had been put down for Eton, but that the higher fees were, by 1923, beyond his parents’ means. John’s daughter Charlotte explains how this obstacle was overcome:

My grandfather, having been ruined by what he used to refer to as ‘the city boys’, was helped out with my father’s education by his brothers and sisters, all of whom forked out for him for everything … He couldn’t go to Eton; they had to settle for Cheltenham, because of the lack of pennies in the coffers.

With the help of the family, John left Clifton House for Cheltenham College in December 1922. The graduation represented no milestone in his life. He later admitted to being ‘sad and depressed to leave’ his prep school, commenting only that ‘it was really just a matter of keeping your temper and sweating it out. In the end you won through.’

John Bingham’s first two novels contain a wealth of hints about his prep and public school days. In Five Roundabouts to Heaven we see an autobiographical picture of a physically unimpressive boy, his poor eyesight and inadequate physique emphasised by thick glasses, waiting inside the school building until his schoolmates had dispersed and he could emerge without fear of being bullied or chivvied.

John was ragged mercilessly at school, as happens to all boys who have a particular phobia; small boys have a nose for discovering weakness and punishing it relentlessly. John’s weakness was a fear of confined spaces. His schoolmates cheerfully exploited that by bundling him into a trunk and closing the lid. The horror of being shut in a tiny space was exacerbated by the presence of several dead moths on the bottom of the trunk. With his face pressed against them he was terrified, and for all his life had a horror of moths.

Success at public schools at that time depended principally on athletic ability and secondly on academic skills. With his poor eyesight he had little chance of achieving distinction as an athlete, and while he did eventually play rugby for his house third XV, this was a modest achievement.

Academically, he performed no better than average. He had not spent his childhood among intellectual parents. By himself he was a voracious reader, but his parents encouraged neither reading nor other intellectual pursuits. In his own eyes he was a poor specimen; in his first novel he refers to himself as ‘an influenza germ’ in the eyes of a schoolmate. With these deficiencies, perceived and actual, he turned up for his first term at Cheltenham College.

There were three options of study open to him: classical, military and modern. The classical side was the preserve of the better brains, providing, via the university, access to the professions. The military option was a fast track to the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, and the modern side contained boys who had not been identified as belonging to the top stream but who might distinguish themselves academically and become candidates for Oxford or Cambridge. If so, they would stay on for the Sixth Form. The young Bingham was enrolled to study the modern curriculum.

Maurice gave his London address on the college application form, but John, a boy who had grown up with space and land around him, was quite unprepared for life at Cheltenham. The college is compact, built around the playing fields, buildings clustered together. It more resembles a modern university campus than an ancient public school like Harrow or Eton, which effectively occupy the entire town that houses them.

John, used to roaming around his grandfather’s estate, was appalled by the layout of the college. From the start he felt constrained, trapped, and he yearned for air. The experience of having several hundred boys as close neighbours was also unsettling for an only child.

Initially his academic performance was undistinguished but adequate. In his first term he finished fourteenth in a class of twenty-one, showing ability in English, French, Latin and drawing. English, particularly, seemed his forte, as he finished second in his class.

As he worked his way up in the school his academic performance fluctuated dramatically. It is clear that, when he applied himself, he could outperform his peers but it is equally clear that he rarely applied himself more than was required to steer a middle course.

Teenage boys need role models and it seems unlikely that John was finding them at home. Maurice was achieving little that might impress his son during that period. The year 1925, moreover, had seen another member of his family humbled. Maurice’s younger brother Denis was involved in a sensational divorce case. He was cited as co-respondent when a fellow officer sued to divorce his wife for adultery. Divorces of notables were given considerable tabloid space in the 1920s and the mournfully sentimental letters from Denis to the lady in question were splashed across the popular papers. The affair was given added spice by the fact that she was a master of foxhounds, a detail that the press were delighted to stress to maximum effect. John, with the prurience of a sixteen-year-old boy, cut the sordid, explicit clippings from the popular newspapers and pasted them into his scrapbook.

When he reached the Middle Fifth Form in 1925/6, he evidently encountered an encouraging teacher, probably a teacher of English: suddenly his academic performance improved in stellar fashion. From being an undistinguished scholar consistently in the lower half of his class, he leapt to the top, finishing second in a class of twenty-three and first in his class for English, and maintained this throughout that academic year. When he had been considered a mediocre student, he was placed at the front of the class and was able to read everything on the blackboard. Having distinguished himself, he was moved to the back of the room among the better scholars and had trouble reading anything on the board because of his poor eyesight. He began to write short stories and verse, submitting pieces for the school magazine and selling a story to H. G. Wells for a magazine he edited. For this he received the unimaginable sum – for a seventeen-year-old – of five guineas, a reward that impressed his father vastly more than his being published in a magazine edited by a left-winger.

Boys on the classical side were expected to win at least a place, preferably an open scholarship, to Oxford or Cambridge. Boys on the military side needed to achieve decent grades to be accepted to Sandhurst, but for a boy of average ability, stuck in the Fifth Form on the modern side with less incentive to perform, there was a tendency to question the point of it all.

By the academic year of 1926/7 it was clear that John would not make it into the Sixth Form, a prerequisite for applying to university. He merely had to serve one more year before leaving school and heading into the world. With no goal to motivate him, in that year, unsurprisingly, he came in seventeenth, thirteenth and tenth out of twenty-six boys in the three terms.

In his second year at Cheltenham he had joined the Officers’ Training Corps, where he was determined to do well. He rose to be a sergeant, passed his Certificate A and was a first-class signaller. This would have been a key to gaining his father’s respect; certainly, with his poor eyesight, there was no chance of a conventional military career.

In spite of these modest successes, he still lacked confidence and held a jaundiced view of himself throughout his time at Cheltenham. To illustrate this we need read just one passage from his first novel, My Name Is Michael Sibley. In this piece of fiction, he has Sibley spend part of his annual summer holiday with his Aunt Nell, a splendidly aggressive woman with a grand house and estate. Despite a domineering manner, she is fond of Sibley and takes an interest in his performance at school. Cross-examining him on his progress, she succeeds in making him deeply uncomfortable. When he arrives at her door, she greets him with a gruff welcome, demanding to know if he has won his rugby cap. When Sibley answers that he plays for his house side, she booms, ‘Not good enough. Not good enough by a long chalk!’ She turns to cricket, and Sibley replies that his eyes aren’t good enough for him to play in the first XI. Finally, she demands if he is in the Sixth Form. By now, thoroughly despondent, Sibley, ‘blushing crimson’, mutters that this distinction, too, is beyond his grasp.

‘God bless my soul, Michael!’ Aunt Nell thunders. ‘What are you good at?’ Sibley collapses and replies that he isn’t particularly good at anything.

Aunt Nell, who leaps from the pages of Michael Sibley, is modelled on his great-aunt, the Hon. Mrs Burton Percy Bingham (1869–1935) of Ivy Mount House, Athenry, Co. Galway; John spent part of each summer in the west of Ireland to keep alive his connection with the region. She is described vividly in the 12 October 1900 issue of Golf Illustrated:

Mrs Bingham, who was both niece and daughter-in-law of the late Lord Clanmorris, is well known as a good all-round sportswoman, and though punting, so far, takes first place in her affections, she is keen on all games and devoted to country life.

At the end of John’s third year in the school an event occurred that was to have a lasting impact on him. The assistant housemaster in Cheltondale House was a 43-year-old man named Laurence Shuttleworth. Judging from the account in Michael Sibley, Shuttleworth was a retiring man, ineffective as a disciplinarian, one of those teachers who are mercilessly ragged by boys.

Shuttleworth’s wife suffered a prolonged illness before dying of cancer on 24 June. On the same day her bereft husband took his service revolver and shot himself in the head. His suicide haunted John. Schoolchildren are callous creatures and the sport of ragging a mild or ineffectual master is common. Suddenly John saw another side to the man’s tortured life. When the news reached the boys in their study hall, the chattering and giggling was offensive to John and his friend John Parks. They discussed Shuttleworth’s action and the morbid cruelty of the boys for whom the suicide was simply more sport.

John began to understand that schoolmasters have a life outside the classroom, that they suffer from the same desires and needs as the rest of the human race. Shuttleworth had found a refuge with his wife. There he had his private life, his books, the comfort of married life. When his wife died, he was unable to look forward with any pleasure to a life alone, and promptly took his own life.

If we accept the picture of Sibley as a schoolboy as substantially autobiographical, we can envisage the young Bingham as a loner, an only child who had few friends at Cheltenham. Throughout his later written work this theme of loneliness returns. He believed deeply that human beings should be strong enough to deal with events that threatened them; he placed huge emphasis on being able to cope. Yet, when confronted with an example of the blind terror of facing a life alone, he shows a deep compassion. It was an emotion that he personally was able to understand, and the memory of Shuttleworth’s solution remained powerful for him.

It was during his time at Cheltenham that he had begun to write. Two examples of his work, cleverly contrived and bristling with the pretentious style of an adolescent writer, were published in The Cheltonian, the school magazine, in his third year.

The first of these, drawing from the story of Agamemnon returning from the Trojan War, has a hint of the future mystery writer. The second, an ambitious piece of romantic verse, has more than a touch of the Irish poet William Butler Yeats, who was swiftly making a name for himself in London and Ireland. From 1916 to 1929 Yeats lived at Thoor Ballylee at Gort, near Galway, a short distance from John’s great-aunt’s house at Athenry, and the poet would have been an iconic figure for a romantic young Anglo-Irishman. The lilting anapaestic rhythm has a distinct, haunting flavour of the Binghams’ homeland of western Ireland, as the first two stanzas show:

‘The Isle of Enchantment’

Far to the east lies the Isle of Enchantment

Girded by reefs whereon murmur slow waves:

Lazy lagoons with gentle caresses

Creep through the coral and lap in the caves.

Hard by the shore stands a magical palace,

Pearly its walls and jasper its floor;

There as a maiden I dwelt in the forest,

Thence would I go to dream by the shore.

Bingham’s time at Cheltenham, which came to an end in July 1927, was, as his son describes it, ‘undistinguished’. Like many schoolboys of that era, he neither enjoyed it nor hated it. Public school was a rite of passage to be endured; one made friends, gradually discarded them later, always recognised the kinship of the Old School Tie and occasionally returned for Speech Day and similar occasions. It was a life apart, emotionally far from home, and boys became part of an isolated community that had little or no relationship to the world beyond its walls.

In later years Bingham was reticent about his schooldays. The only mention he made of it to his children was when he recalled a visit of his parents to the school. On one Speech Day Maurice and Leila had appeared, dressed as though they were destined for Royal Ascot or Eton, rather than the rituals of an afternoon at Cheltenham. He was mortified by his father’s tailcoat and topper, by his mother’s flowing dress, parasol and splendid hat.

Without fanfare, without prospects, he had no easy entrée to a career, yet he appears not to have seen the matter as urgent. One idea, however, had begun to form in his mind. A voracious reader, he had consumed the works of Edgar Wallace, the most popular crime writer in Britain in the 1920s. It was from Wallace’s work that he learned of the Colonial Service and decided that it sounded glamorous, vaguely clandestine. In the summer of 1927 he applied and was invited to an interview. Once more, he records events in Michael Sibley, painting himself in a poor light. He imagines that the interviewer recorded that he was ordinary in appearance, ill at ease, bereft of any real academic qualification and, that most damning description, a spectacles wearer.

That is how he chose to record the interview in the fiction, principally to enhance the picture that he paints of Sibley as a weak, unimpressive character. The truth is more complex, as he recorded in later life:

Largely because I had read deeply about Colonial District Commissioners in the works of Edgar Wallace, I, too, wanted to be a Commissioner. But the Colonial Office, as it was then called, only took would-be District Commissioners from the age of 21. I was 18 or 19. To fill in the intervening years, a job would have been convenient. But with no experience and no special skills, a job eluded me. I was unemployed and apparently unemployable.

The interviewing officer suggested that it would help his application if he could add a couple of languages to his qualifications and reapply when he reached his twenty-first birthday in November 1929. This sound advice posed problems, however. Maurice and Leila were struggling financially and were in no position to fund a jaunt abroad, a jaunt that would stretch two years into the future.

In a short reflective piece of writing from 1985 or 1986 he comments, ‘Those were the days when aunts and uncles often had money to spare and if somebody liked you he (or she) paid for a sojourn abroad.’ His eccentric Cloete aunts, equally, had no money to spare; indeed, Aunt Effie was perennially involved in litigation and permanently trying to relieve any available relative of funds to promote her ‘case’, a complicated lawsuit whose outcome, she assured everyone, would make them mountainously rich.

Once again Maurice’s brothers and sisters chipped in. They had rallied round to ensure that John went to a decent school and once more they saw the value of an extended trip to France and Germany. But their bounty was wearing thin and this was to be the last time that the family bailed Maurice and Leila out.

An advertisement in The Times provided the solution for the first leg of the journey: the owners of Château de la Matholière in the Sologne welcomed a small group of the right people to their estate to learn French language and customs. In an exchange of letters they confirmed that they did have space for a young Englishman to join them in September. As to the next stage, there was ample time to make arrangements as John’s stay in France would last until the following July.

In September 1927, with his next two years settled and the prospect of a job on his return, he set off on a trip that would be instructive and pleasurable. It would also fashion his political beliefs and, indirectly, influence his choice of career twelve years later.