9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

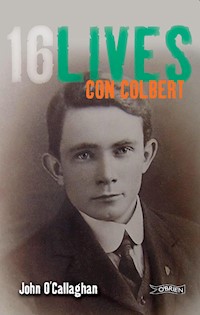

Con Colbert was one of the lesser-known leaders of the 1916 Rising. From a comfortable background in Newcastlewest, County Limerick, he moved to Dublin aged fifteen and worked as a junior clerk in a bakery. Already politically radicalised, he became captain of the first troop of Na Fianna Éireann, the republican boy-scout movement. An unswerving patriot and idealist, he worked tirelessly for the dream of an Irish-speaking, independent republic. Even before his execution, Colbert was held up as an icon and a role model for the Irish Volunteers. Colbert commanded a company at Watkins' Brewery and at Jameson's Distillery during the Rising. Inspiring men by example, he showed no fear in the face of danger and confronted his own death with equanimity. Con Colbert was executed at Kilmainham Gaol on 8 May 1916, aged twenty-seven.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

The 16LIVES Series

JAMES CONNOLLY Lorcan Collins

MICHAEL MALLIN Brian Hughes

JOSEPH PLUNKETT Honor O Brolchain

EDWARD DALY Helen Litton

SEÁN HEUSTON John Gibney

ROGER CASEMENT Angus Mitchell

SEÁN MACDIARMADA Brian Feeney

THOMAS CLARKE Helen Litton

ÉAMONN CEANNT Mary Gallagher

THOMAS MACDONAGH Shane Kenna

WILLIE PEARSE Roisín Ní Ghairbhí

CON COLBERT John O’Callaghan

JOHN MACBRIDE Donal Fallon

MICHAEL O’HANRAHAN Conor Kostick

THOMAS KENT Meda Ryan

PATRICK PEARSE Ruán O’Donnell

DEDICATION

I gcuimhne ar John O’Callaghan – m’athair agus mo chara.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Almost a century after his death, this is the first full-scale biography of Con Colbert. There is no guarantee of another. So, rather than confining his voice to footnotes or appendices, Colbert’s personal letters and poetry are placed front and centre in the text beside the narrative of his actions. Thanks to the 16 Lives series co-editors, Ruán O’Donnell, who invited me to write this book, and Lorcan Collins, for his enthusiastic support throughout. The staff of a variety of archival institutions were most obliging: the Allen Library, the Irish Capuchin Provincial Archives, the Fusiliers Museum of Northumberland, Kilmainham Gaol, Limerick City Library, the Military Archives of Ireland, the National Archives of Ireland, the National Archives of the United Kingdom, the National Library of Ireland, the National Museum of Ireland, the Pearse Museum, and University of Limerick Library Special Collections. A host of individuals were generous with their knowledge and their time: Ray Bateson, Niall Bergin, Noelle Cawley, Finbarr Connolly, Patricia Conway, Liam Clarke, Con Colbert, John Colbert, Brian Crowley, Liam Doherty, Úna Gonley, Simone Hickey, Brian Hughes, Lar Joye, Commandant Pádraig Kennedy, Rosemary King, Jim Langton, Corporal Andrew Lawlor, John Logan, Des Long, Patrick Mannix, Séamus McAlwee, James McDonald, Eamon Murphy, Sarah Nolan, Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc, Mick O’Farrell, Maeve O’Leary, Seosamh Mac Muirí, Elaine Sisson, and Tom Toomey. Mairéad agus Seán Óg, is aoibhinn liom sibh.

16LIVES Timeline

1845–51. The Great Hunger in Ireland. One million people die and over the next decades millions more emigrate.

1858, March 17. The Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Feni-ans, are formed with the express intention of overthrowing British rule in Ireland by whatever means necessary.

1867, February and March. Fenian Uprising.

1870, May. Home Rule movement founded by Isaac Butt, who had previously campaigned for amnesty for Fenian prisoners.

1879–81. The Land War. Violent agrarian agitation against English landlords.

1884, November 1. The Gaelic Athletic Association founded – immediately infiltrated by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

1893, July 31. Gaelic League founded by Douglas Hyde and Eoin MacNeill. The Gaelic Revival, a period of Irish Nationalism, pride in the language, history, culture and sport.

1900, September.Cumann na nGaedheal (Irish Council) founded by Arthur Griffith.

1905–07.Cumann na nGaedheal, the Dungannon Clubs and the National Council are amalgamated to form Sinn Féin (We Ourselves).

1909, August. Countess Markievicz and Bulmer Hobson organise nationalist youths into Na Fianna Éireann (Warriors of Ireland) a kind of boy scout brigade.

1912, April. Asquith introduces the Third Home Rule Bill to the British Parliament. Passed by the Commons and rejected by the Lords, the Bill would have to become law due to the Parliament Act. Home Rule expected to be introduced for Ireland by autumn 1914.

1913, January. Sir Edward Carson and James Craig set up Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) with the intention of defending Ulster against Home Rule.

1913. Jim Larkin, founder of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) calls for a workers’ strike for better pay and conditions.

1913, August 31. Jim Larkin speaks at a banned rally on Sackville (O’Connell) Street; Bloody Sunday.

1913, November 23. James Connolly, Jack White and Jim Larkin establish the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) in order to protect strikers.

1913, November 25. The Irish Volunteers founded in Dublin to ‘secure the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland’.

1914, March 20. Resignations of British officers force British government not to use British army to enforce Home Rule, an event known as the ‘Curragh Mutiny’.

1914, April 2. In Dublin, Agnes O’Farrelly, Mary MacSwiney, Countess Markievicz and others establish Cumann na mBan as a women’s volunteer force dedicated to establishing Irish freedom and assisting the Irish Volunteers.

1914, April 24. A shipment of 35,000 rifles and five million rounds of ammunition is landed at Larne for the UVF.

1914, July 26. Irish Volunteers unload a shipment of 900 rifles and 45,000 rounds of ammunition shipped from Germany aboard Erskine Childers’ yacht, the Asgard. British troops fire on crowd on Bachelors Walk, Dublin. Three citizens are killed.

1914, August 4. Britain declares war on Germany. Home Rule for Ireland shelved for the duration of the First World War.

1914, September 9. Meeting held at Gaelic League headquarters between IRB and other extreme republicans. Initial decision made to stage an uprising while Britain is at war.

1914, September. 170,000 leave the Volunteers and form the National Volunteers or Redmondites. Only 11,000 remain as the Irish Volunteers under Eóin MacNeill.

1915, May–September. Military Council of the IRB is formed.

1915, August 1. Pearse gives fiery oration at the funeral of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa.

1916, January 19–22. James Connolly joins the IRB Military Council, thus ensuring that the ICA shall be involved in the Rising. Rising date confirmed for Easter.

1916, April 20, 4.15pm.The Aud arrives at Tralee Bay, laden with 20,000 German rifles for the Rising. Captain Karl Spindler waits in vain for a signal from shore.

1916, April 21, 2.15am. Roger Casement and his two companions go ashore from U-19 and land on Banna Strand. Casement is arrested at McKenna’s Fort.

6.30pm.The Aud is captured by the British navy and forced to sail towards Cork Harbour.

22 April, 9.30am.The Aud is scuttled by her captain off Daunt’s Rock.

10pm. Eóin MacNeill as chief-of-staff of the Irish Volunteers issues the countermanding order in Dublin to try to stop the Rising.

1916, April 23, 9am, Easter Sunday. The Military Council meets to discuss the situation, considering MacNeill has placed an advertisement in a Sunday newspaper halting all Volunteer operations. The Rising is put on hold for twenty-four hours. Hundreds of copies of The Proclamation of the Republic are printed in Liberty Hall.

1916, April 24, 12 noon, Easter Monday. The Rising begins in Dublin.

16LIVES - Series Introduction

This book is part of a series called 16 LIVES, conceived with the objective of recording for posterity the lives of the sixteen men who were executed after the 1916 Easter Rising. Who were these people and what drove them to commit themselves to violent revolution?

The rank and file as well as the leadership were all from diverse backgrounds. Some were privileged and some had no material wealth. Some were highly educated writers, poets or teachers and others had little formal schooling. Their common desire, to set Ireland on the road to national freedom, united them under the one banner of the army of the Irish Republic. They occupied key buildings in Dublin and around Ireland for one week before they were forced to surrender. The leaders were singled out for harsh treatment and all sixteen men were executed for their role in the Rising.

Meticulously researched yet written in an accessible fashion, the 16 LIVES biographies can be read as individual volumes but together they make a highly collectible series.

Lorcan Collins & Dr Ruán O’Donnell, 16 Lives Series Editors

CONTENTS

Introduction

Chapter 1: Home Life and Formative Influences

Chapter 2: Cultural Nationalist

Chapter 3: Na Fianna Éireann

Chapter 4: The Volunteers

Chapter 5: The Rising

Chapter 6: Court Martial and Execution

Chapter 7: Conclusion

Bibliography

Notes

Index

Introduction

In Newcastlewest in County Limerick, close to where Con Colbert was born and spent his childhood, a memorial to republican martyrs was erected in 1955. A catalogue informs visitors that Colbert fought in the General Post Office (GPO) during the 1916 Easter Rising, and that he was executed on 7 May. Neither part of this statement is factual. He was elsewhere in Dublin city centre – first in Watkins’ brewery on Ardee Street and then in Jameson’s distillery on Marrowbone Lane. He was executed on 8 May. Such inaccuracies might seem harmless in themselves – and this first instance merely reflects the centrality of the GPO to how the Rising is remembered – but they are indicative of the manner in which man and myth can become one.

The cumulative effect of a variety of similar errors, superficially innocuous as they may be, combined with a number of pointed and persistent misrepresentations, has been to obscure Colbert’s real role in the preparations for the rebellion, in the battle itself and even in his court martial and execution. The purpose of this book is to bring as much clarity to these issues as the sources will permit, and to present as realistic a portrait as possible of what type of a person Colbert was. Colbert never consciously cultivated a reputation for himself. Others decided to do that after his execution. To encounter a historical figure is all too often to encounter fiction. The first duty of any biographer should be to afford a subject, and an audience, the appropriate complexity – in this case, to separate the man and the myth. Only then is an honest assessment of a life possible. And it should be for his life as much as for his death that Colbert is commemorated.

The Rising was a spectacular display of resistance to the British empire near the height of its power and on an active war footing. The rebel leaders anticipated that they were striking a decisive blow in a struggle for national liberation. The Proclamation of the Republic invoked a tradition of militant resistance, envisioned an independent Ireland, and proposed a pluralist society resting on an anti-imperial foundation. But this was not a simple story. The political and cultural history of Ireland in the years before 1916, and the history of the Rising itself, remains enigmatic and it would be insensitive and irresponsible to draw simplistic conclusions, whether celebratory or condemnatory, on intricate matters.

While overt republicanism and separatism were fringe phenomena during the first decade and a half of the twentieth century, subsequent events would demonstrate that there was an extensive slumbering sympathy for radicalism that was roused by the Rising. Opposition to continuation of the Union of Great Britain and Ireland with direct government from London was the norm, yet the primary proposal of the nationalist majority was for no more than Home Rule, a limited measure of control over domestic affairs for a Dublin parliament. As well as constitutionalist principles, there was a strand of imperial sentiment running through sections of the Home Rule movement, but its moderate claim reflected realism regarding the balance of power in Anglo-Irish relations, rather than idealistic aspiration or conviction.

Unionists, predominantly Protestant and with their power base in northeast Ulster, feared Home Rule as a threat to their political, cultural, civic, economic and religious interests. The nationalist strategy assumed that when the government eventually conceded a compromise reform, which could not be denied indefinitely, unionists would consent once convinced that it was a benign measure. This gamble, democratic as it was, failed to understand the depth of feeling inherent in the unionist – British – imperial dynamic, and was lost at huge cost. Unionism had evolved from a more conciliatory phase earlier in the century to the point where it resolutely refused any concession. Unionists now demonstrated a readiness to defy the common will and even parliamentary opinion.

When Home Rule legislation was introduced in 1914, proviso was made for the exclusion of Ulster.1 So it was not because of the Rising that partition reared its head. The concept had already entered the public debate and the precedent had been set: Home Rule, if and when it was enacted, would not apply to the whole country. The onset of world war left an uncertain and uneasy situation hanging in suspended animation.

The relevance of 1916 to all of the island’s understanding of its past is acute. Turning the Rising into a historical cult prevents real debate and only baits shallow sensibilities. Defending its ideals does not have to supercede reasonable concerns about its democratic credentials and the appropriateness of the use of physical force. On the other hand, the false reduction of the rebels to nothing more than vacuous fanatics, and the mocking of its commemoration, is a pernicious form of historical politicking and part of a lamentable reaction to latter-day imperatives. The Troubles meant that from the late 1960s, the historicisation of the claim to national self-determination and the nature of Irish state formation became more than purely academic affairs. Historians of the Rising found themselves arbitrating on issues critical to the contemporary conflict, particularly on competing legitimations of government authority, the use of violence to overthrow such authority, and the question of a mandate for such action. The task that some historians set themselves was to reconcile opposition to militant republicanism with the revolutionary origins of the Free State.2 An essential point, however, is that the ‘intimidatory gunman lurking in the shadows’ of the Union was British.3 Britain had never succeeded in fully integrating Ireland into the Empire, and a critical factor in the structure of the Union was the overwhelming superiority of British firepower. Ireland was part of a democracy in 1916, albeit an already flawed one that was further grievously undermined by the extra-parliamentary tactics of Ulster unionism between 1911 and 1914. The rebels did not introduce the gun to Irish politics. It was already present.

Since their executions, the lives and deaths of the sixteen men who form the subjects of this series of biographies have been the playthings of politicians, revolutionaries, journalists and polemicists, as well as historians. Their memories have been hijacked and their legacies appropriated, to be shaped by those with an agenda other than historical objectivity. Approaches have veered wildly between secular sanctification and demonisation. Some commentators have adopted a deliberately derogatory and anachronistic style, in order to challenge those who would justify the persistence of physical-force tradition by reference to the ideology of the Rising and its effect on public opinion. Admirers are charged with knowingly providing succour to undemocratic insurrectionists.

The actions of a small number of individuals, representative perhaps of only a minority, clearly had a profound impact, but the influence of the Rising on subsequent political events and the responsibility or otherwise of its abettors for later violence is not the issue here. The aim is to present a fair and balanced biography of Con Colbert, who was in many ways an ordinary man, but one who did some extraordinary things in extraordinary circumstances. To what degree he played a role in fomenting those circumstances is arguable.

The very fact of his execution has ensured Colbert’s continuing historical resonance and relevance. Imagine for a moment that he had not been executed – would he still warrant a biography? Was what he did unique, or were there many who made similar or more important contributions to Irish politics and society in the same period? If he had not been executed, would it have been a glaring omission? How important was the element of chance? The rationale for his execution, and the capricious process behind it, must be examined closely.

Of the sixteen men executed, Colbert is among the lesser known. In the public mind, as in major studies of the Rising, he tends to occupy a peripheral role. Because of his lower profile, he has also not been a target of character assassination. If anything, the opposite has been the case. When he has received sustained or detailed attention, it has been uncritical and unquestioning. He was not one of the seven signatories of the Proclamation. He was not a battalion commandant, but held relatively junior rank. He was not a renowned orator, ideologue or statesman. But his commitment inspired his colleagues. His loyalty and competence won their admiration and gained him the trust of the Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), which planned the Rising. There is no shortage of testimony from Colbert’s contemporaries as to his disposition and ability, and how these qualities inspired respect, but there are relatively few of his own words by which to judge him along with his actions. He did not leave a diary, and there is no indication that he ever kept one. His poetry was not designed for public consumption. It was somewhat formulaic, and repetitive of standard nationalist imagery. His thematic range was limited. His compositions fit snugly in the genre of romantic nationalism. A representative selection of titles is ‘The call of Éireann’, ‘How to be a patriot’, ‘To be free’ and ‘We must be free’.4 Ireland as mother was a habitual motif. Colbert died at the age of twenty-seven. Of the executed men, only Ned Daly and Seán Heuston were younger. Tom Clarke was three decades older.

Colbert wrote no fewer than eleven letters to family and friends on the night before his execution. There are several accounts of his attitude and conduct at this point, but one should be cautious in drawing wide-ranging conclusions from such an exceptional situation. One record of his trial suggests that he was submissive, and this could be interpreted as Colbert wishing his ordeal of failure to end; a conflicting version suggests that he attempted to assert himself in the face of falsehoods. Three letters to a brother in America, most likely written between 1909 and 1911, do unveil something of the man’s character and his thinking on the issues of the day. Unfortunately, letters from his brother to Con do not seem to be extant. However, there is enough evidence in the few letters which survive, as well as in his behaviour, to suggest that the traditional conception and portrayal of Colbert needs to be modified.

Unlikely ever to have considered the possibility that historians would study these documents a century after his death, Colbert displayed more awareness of his own normality and insight into his own flaws than is evident in most fawning secondary accounts. He may not have had many, or perhaps even any, vices, but he did have the usual human concerns about things like money, fleetingly at least. Second-hand testimony suggests that he seems to have agonised over his romantic relationships with women. It might be unfair to say that he had a curious attitude to romance, but he certainly prioritised his public life over his private life. His choices in this regard were, on the surface at least, unusually selfless, and lack of evidence means there is no way to delve deeper. The insights into his character provided by his letters make it much easier to empathise with Colbert the man, as opposed to Colbert the symbol of the Rising.

In a letter dated 6 February, in what the content indicates was probably 1909, Colbert wrote to ‘A Seaghan dílis’ (Dear John), as he always addressed his brother in California:

I am sorry that you should turn to flattery as a means of complimenting me. I am not eloquent, nor is my patriotism above that of the ordinary man. I try to have a real unselfish love for Ireland but human nature often asserts itself and makes me serve Ireland – sometimes that I might gain fame, at others that it might be a means to the end of serving myself; however I overcome these feelings to as great a degree as I can do; and try to make every action of mine acceptable to the good of my country.5

These frank admissions provide a revealing glimpse into the mind of a twenty-year-old who seems somewhat unsure of himself. He is striving to carve out a role. His uncertainty is just as striking as his ambition. His hope is for promotion within the movement, rather than simply self-promotion, and he is struggling to enhance his reputation rather than gain notoriety. This was a balancing act at which he became more adept over the following years.

Michael Madden, who in 1983 produced Captain Conn Colbert. Defender Watkins’ Brewery Marrow Bone Lane Area, Easter Rebellion 1916, described his work not as a biography but as a ‘pen picture’. Characterised by an explicit religious tone, it exemplified the hagiographic approach to the rebels which came into vogue soon after the Rising and held sway in some quarters for several decades. Madden depicted Colbert in messianic terms, and as a martyr:

The man of deep religious faith in daily communication with his God; a man who hated injustice and loved his country and his people; a man who fitted himself mentally and physically for the task of leading his people from Egypt to the Promised Land. A soldier eager not for the glorification of war but for the God-given right to free his country from foreign domination. A captive in the hands of the enemies of his country in bleak and cold Kilmainham Gaol awaiting a martyr’s death with belief in the justice of his cause and in God’s mercy … I can see God’s Son who came on earth to liberate enslaved mankind and who was also immolated unjustly at Eastertide on a gibbet, waiting on that 8th of May morning in 1916 to welcome Con Colbert home at the end of the wearying day.

This account is typical of representations of the executed rebels as ‘a band of pure-souled patriots’. Joseph Lawless, a veteran of the Rising, subscribed to this notion:

All, without exception, were governed by a simple honest adherence to the pure ideal of National Freedom. In not one of them was there a hint of mean thought or ulterior motive; but on the contrary, it was abundantly evident that the normal self-interest or concern in personal affairs was placed in a subordinate position in relation to the pursuit of the ideal. … the rank-and-file who strove to emulate the shining example and follow the precept of those whose direction of the national Cause had to them the appearance of Divine inspiration.6

This passage comes from Lawless’ Witness Statement, submitted to the Bureau of Military History in 1954. The Bureau’s Witness Statements, Volunteers’ accounts of their political and military activities between 1913 and 1921, give voice to many otherwise silent participants, revealing their motivations and aspirations. They were recorded in the late 1940s and 1950s and can be problematic in terms of bias, memory, conjecture, inaccuracy and retrospective justification. Furthermore, the process surrounding the creation and collection of statements was on occasion subject to interference from vested interests. Some testimonials were bluntly prejudiced by personal relations and factional loyalties, but many are remarkably candid and convey something of the atmosphere, feelings and emotions of the experience of being a Volunteer. Comments relating to the leaders of the Rising were generally gushing in their praise, designed to lionise the dead men, but the Statements contain valuable evidence.

Stripping away the effusive accolades, however, it is also plain that many of Colbert’s circle harboured a deep affection for him. Gary Holohan’s tribute was all the more sincere for its simplicity: ‘one of my dearest and best friends. Poor old Con Colbert. Of all the men who fought in the Rising there was no truer or stouter heart’.7

Even before his death, Colbert had been placed on a pedestal as a role model. When Patrick Pearse wished to appoint a bilingual physical education and drill teacher in his school, Scoil Éanna, Colbert was ideally suited on both counts. He held the position from late 1910 to 1916.8 He declined the offer of a salary, unwilling to accept remuneration for what he considered to be work in the national cause. Colbert apparently reacted with such indignation that Pearse had to apologise and drop the idea of paying him.9 In An Macaomh in May 1913, referring to his regular school staff, Pearse hailed ‘gallant Captain Colbert for drill and physical culture’.10 One of the schoolboys quickly latched on to the compliment. On 24 May 1913, An Scoláire, the Scoil Éanna student periodical, carried an open letter to the ‘Gallant Captain Colbert’:

Friend, So the Macaomh hailed you, proving you a man of worth, as it has paid no compliments to mediocrities. You have done good things in and outside Scoil Éanna. No doubt you will do good things till the day you die. In heaven, I feel sure, you will drill the angels et the saints, not even letting St. Peter off. You understand the grandeur of Ireland. You know the greatness of the task which no one has finished yet. You would ever fight your foes, but never abuse them. The rascals have said before now you are small in size. I pray the Lord to give us more men and women with souls as large as yours.11

‘Con was on the small side’, according to one observer.12 Colbert’s small stature – accounts of his height vary from 5 feet to 5 feet and 4 inches, although his build is almost universally described as ‘stocky’ – had not gone unnoticed by ‘the rascals’ in the school, but the author of this piece certainly seemed to have been impressed by the force of his personality.

After the Rising, Colbert was not only a role model, but also a martyr. Political demonstrations were banned, so one manifestation of the growing public sympathy for the Rising and its lost leaders was the phenomenon of memorial masses. As early as 13 June 1916, TP O’Connor recounted to David Lloyd George the quaint tale of one little Dublin girl who successfully called on ‘Saint Pearse’ to convince her hesitant mother to buy her a new hat. Another apocryphal story O’Connor told Lloyd George was of the priest who, while giving the last rites to Con Colbert and assuring him that he would go to Heaven, begged his intercession to obtain an ‘intention’, which was ‘an unfulfilled though usually secret wish of a religious character’.

He [the priest] had desired the fulfilment of this ‘intention’ for many years but [he told Colbert] that if he obtained it within five days after Colbert’s execution, he would know that Colbert’s intercession had obtained it for him. The ‘intention’ was realised within three days after Colbert’s execution.13

The process whereby the spiritual credentials of the rebels and the sacred nature of their cause was emphasised gathered momentum from July 1916, when a popular Dublin magazine, the Catholic Bulletin, began a to carry a series of features entitled ‘Events of Easter Week’, cataloguing, over successive months, the religious qualities of the executed men. The garrisons had frequently recited the rosary and were often visited by priests. Many individuals had prepared for the Rising with devotions over the Easter weekend. Roger Casement converted from Protestantism to Catholicism shortly before his execution, and the other fifteen were all at least nominal Catholics. Some of them had lapsed from practice, including doubting Thomas MacDonagh and sceptical Seán MacDiarmada, but the anti-clerical Fenian Tom Clarke was the only one who did not seek solace in the Church when facing execution.

The piety of the rebels generally was not necessarily exceptional, however, and was probably a fairly representative reflection of the level of religious practice in Irish society at large. The cumulative effect of such uncritical celebration was twofold. Firstly, popular perception came to automatically conflate Catholicism and the Rising, overlooking the non-sectarian and pluralist sentiments of the Proclamation. Secondly, it led to the projection of unrealistic saintly images of the fallen. Volunteer Seán Prendergast reflected on the impact of the Bulletin pieces on interned rebels:

To say that we were stirred by the splendid portrayal of good and righteous men would be to use quite a mild term. The few copies that were available in the camp were eagerly sought after, read, and even copied. It would be safe to say that we felt highly honoured by these grand and edifying tributes to our dead leaders.’14

Colbert was described as maintaining the highest standards of piety even in the face of his impending demise.15 His favourite phrase, according to his sister Lila, was ‘for my God and my country’.16 He had been devout, but he was now presented as a symbol or icon of impossibly elevated morality, rather than as a complex human being with flaws as well as virtues, to be judged in the context of his times. He became a personification of the ‘faith and fatherland’ version of Irish history. In the late 1940s, Madge Daly, sister of Ned Daly and sister-in-law of Tom Clarke, labelled Colbert ‘a soldier and a saint’. Because he followed his duty to God and country, she claimed, ‘regardless of censure, no matter what the source … he lived and died happily’.17 Such claims are frequent and have to be scrutinised rather than dismissed out of hand, but they are also part of the propaganda campaign to venerate the dead.

What motivated Colbert to commit himself to violent revolution? What was the influence of his family background and education? Was he ideologically sophisticated or rigidly narrow-minded? How did his mentality change over time? How was he affected by social factors such as peer pressure? Were his God and his country his only concerns? What kind of a republic was he willing to kill and die for? What did he think would be achieved by the Rising, given the disparity in strength of the respective forces? How did he face his death?