Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

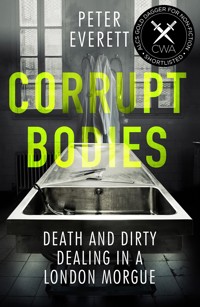

** SHORTLISTED FOR THE CWA'S ALCS GOLD DAGGER FOR NON-FICTION ** In 1985, Peter Everett landed the job as Superintendent of Southwark Mortuary. In just six years he'd gone from lowly assistant to running the UK's busiest murder morgue. He couldn't believe his luck. What he didn't know was that Southwark, operating in near-Victorian conditions, was a hotbed of corruption. Attendants stole from the dead, funeral homes paid bribes, and there was a lively trade in stolen body parts and recycled coffins. Set in the fascinating pre-DNA and psychological profiling years of 1985-87, this memoir tells a gripping and gruesome tale, with a unique insight into a world of death most of us don't ever see. Peter managed pathologists, oversaw post mortems and worked alongside Scotland Yard's Murder Squad - including on the case of the serial killer, the Stockwell Strangler. This is a thrilling tale of murder and corruption in the mid-1980s, told with insight and compassion.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 346

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf: