Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Valley Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

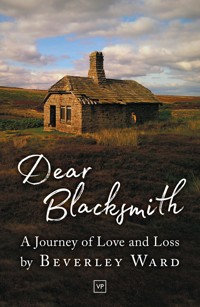

'This wasn't the story I wanted to tell. The end happened in the middle.' Part love story, part grief memoir, Dear Blacksmith recounts the author's brief and unconventional love affair with 'Blacksmith Paul', a maverick who lived out on the moors in the Peak District – and the heart-rending details of her grief after his sudden death, just eight months into their relationship. Adapted from the much-loved blog Swimming Through Clouds, the story is told through a series of searingly-honest diary entries, reflections, and poems addressed to the Blacksmith. In a heartfelt rejection of 'stiff upper lip' culture, 'Writer Beverley' sheds all inhibitions to examine grief at its most raw and brutal; from planning her love's funeral with a family that she'd never met, to learning to live alone again following the loss both of her soulmate and her mother, a few weeks earlier. A complex journey from the depths of sorrow to the beginnings of recovery, this book is a work of extraordinary sincerity; and ultimately, a hard-earned testament to the power of love and the resilience of the human spirit.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 480

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

—————

Dear Blacksmith

—————

Beverley Ward

Valley Press

for Paul

Dear Blacksmith Paul,

If you look at the photos, you might wonder why they seem dark and smudged, even though it’s spring. It’s a new kind of filter on the lens. Called grief. It’s a bit like looking through the rain all the time, or maybe that’s the tears. Hard to tell sometimes.

You’ll notice though the buds on the trees. It’s April now and the magnolia tree outside my window is flowering. I don’t think you ever saw it flower. My daughter doesn’t want to leave the magnolia tree and move house but I can’t live here anymore. Too many things have happened here. I need a fresh start.

Don’t worry, I will take you with me. I’m collecting things slowly that remind me of you, to incorporate into this new life that I have been catapulted into. The one where all our hopes and dreams have been silenced and I am left with fragments of memories. I will find a space where I can put the half-finished lamp that you were making. Someone will know how to wire it, I’m sure. The new place will have a log-burning stove – your family said maybe I can have yours. I know, you told me about the regulations, I’ll work it out, make sure it’s safe. I will prod the embers at night with the poker we made and look at the book of photos and words that I will make just like we planned.

I’ll find someone else to take down your beautiful hooks and find a new wall to fix them onto. I’ll bring some things from my mother’s house too, find a way to make them scenery to some kind of new life that I can’t envisage. Her house is on the market now, you know. I would take you there one more time and show you around properly. You could help me pack things away. You would like to see the family albums. I’ve seen yours now; your mum and I sit and look at them. You were cute. But I’m not surprised.

I’ll bring the clock too. The one my father gave me. You took the mechanism to fix so it has no hands at the moment but that suits me fine. There is no time anymore, or too much time.

I would take you to the park but I see you there anyway. And I would take you back to the house at Redmires where we first walked. But maybe it won’t be the same without the heather. I know it won’t be the same without you.

I miss you and love you,

Beverley Writer

Introduction

It is two years, eight months and four days since my love, Blacksmith Paul, died. A strange day to note you may think, but it has been logged on my calendar for two years, four months and eight days. On that day I was sitting sobbing again in the pale blue room of the hospice, the one just down the corridor from where my mother had also recently died, the one marked ‘Counselling, Do not Disturb’. I was asking when it would end, when I could hope to feel some semblance of normality return. My bereavement counsellor paused, recognising perhaps that I might not like her answer and told me that, statistically-speaking, two years, eight months and four days is the average time it takes to recover from a major bereavement. I broke off from crying to snort with laughter. It was clearly ridiculous. The date seemed to be impossibly far away. It seemed impossible that I could survive for that long. It was also impossible to think that it could ever be over. I put it in my phone, maybe as a date to work towards, maybe as a black joke or ironic statement. 13th November 2018: Grief Ends.

As a writer, I am fascinated by endings and beginnings, by story and narrative. When Paul died just eight months into a beautiful love affair, I couldn’t make sense of it at all. ‘The end just happened in the middle,’ I wrote. It was how I felt. Unexpectedly and completely without warning, his story was over and the story I had been writing in my head (you know the one: unconventional hero rescues unlikely heroine, happy ever after ensues) was over too. The narrative was fractured and the writer (me) was broken. It wasn’t the story I wanted to live. It wasn’t a story I wanted to write. But it was the life I was left with and somehow, it seemed that writing was the only thing I still wanted to do. I didn’t set out to write a memoir. I didn’t even set out to write a blog. I just put words on the page, one after the other, the way other people put one foot in front of the other and I wrote. I wrote to capture my memories and I wrote as a student of my own grief. Mostly, I wrote in order to survive.

It is hard when constructing a memoir to know where to begin and where to stop. I search for a place to start and think of Paul. If this is Paul’s story then it begins back in 1963 with a baby at a mother’s breast. It begins at Hunters Bar, Sheffield, in the rented terraced house on Penrhyn Road, the one over the hedge from my old back garden, the one we could see from my bedroom window as we lay in each other’s arms years later. It begins even earlier than that, with an antique-dealing father and the mother who hoarded treasures like she already knew love would be scarce. It begins with a youthful romance that gave birth to a baby boy. But I am not qualified to write that narrative without Paul here to guide me, not when the mother who nurtured him followed him swiftly out of reach. No, this cannot be Paul’s story.

So perhaps this is our story, his and mine, the story of our love. But when does that story begin? Does it begin back in 1992 when he slept and worked in the blacksmith’s forge on Garden Street, across the yard from the office of Swamp Circus where my I served an apprenticeship in the arts? Does it begin as the sound of hammer on iron rings out across the cobbled yard to the unheated garret where I shiver, attempting to make peace with the taste of soy milk in tea? Or does it start circa 1997 when, as a young divorcee, I was introduced to Paul in The Lescar by our mutual friend, Ed? Does it begin with his thwarted attempts to play Cupid? Or does it start almost twenty years later in 2014, when, at forty-five and fifty-three years of age, Ed reunited us again and we finally fell in love? Perhaps.

But, though this story is our love story, it is also the story of the year following Paul’s death – and though Paul’s presence echoes through those days like the ring of hammer on iron, for most of the story, he is absent. So what’s left is my story, of love, loss and grief – and where does that begin? Does it begin with love or with loss, and how can I separate the two? In order for you to understand the precious love we shared, do I need to write about the other loves who came and went: the one who broke my heart six months before we met, the children’s father who left the year before, my first true love whom I divorced at twenty-six? Do I need to write about the other losses too? The mother whose long dance with cancer ended twelve weeks before Paul’s death, the son whose babyhood was lost to sickness and stress, his older sibling who died on the day of the twelve week scan? Does it go back to the father who died of brain tumours when I was thirty-one, to the inheritance I lost to his second wife? No, I cannot cover it all in one book. My story of love and loss is long.

Still, if I can’t tell you when the story began, I can at least tell you when I began to write it. It was Easter 2015 and I was in the little tutor’s bedroom at the Ty Newydd Writing Centre on the Llyn Peninsula in Wales. It is a place I go to every year, a place where I can be alone but among writers, a space in which I can focus on myself and on my craft. It was only a few weeks after Paul’s mysterious death. The post-mortem took time, his body was still in the mortuary. But the retreat was already arranged, the children’s father already booked to have them. It seemed as good a place to be as any.

That year, I didn’t do much writing. I only wrote one poem. But I also wrote the eulogy for Paul’s funeral and an email to a young widow who had only recently asked me for advice about publishing a book. I remembered that she’d found the act of writing helpful in her grief, and as she was the only person of my generation that I knew who had lost a partner, I reached out to her across the web. She suggested that I sign up to Megan Devine’s Writing Your Grief programme. I needed no encouragement; I knew already that writing would be my handrail in the darkness and the only way I could survive.

I followed Megan’s prompts for thirty days, often writing late at night in snatched moments when the children were asleep, onto a blog that I initially just called ‘griefwriting’. I shared the results with other members of the online writing group and then, one day, I decided to share something with friends on Facebook. They wanted to hear more and so, gradually, I started sharing more of my writing and soon I was creating my own posts. As I watched the numbers of hits on my blog rising from tens, to hundreds and then to thousands, I realised that my writing was resonating far beyond my immediate circle and I changed its title to ‘Swimming through Clouds’. The motif of clouds kept recurring and swimming was one of the activities that kept me sane. When I swim, the world and my cares recede – and when I swim outdoors, suspended between water and sky, I feel part of something bigger. My mind is as still as the water’s surface and I feel at peace. Even in the early days of grief, when I was swimming, I could stop crying. When I was swimming I felt okay. ‘Swimming through Clouds’ seemed to capture something both literal and metaphorical about the way I journeyed through grief.

At first I wrote daily, then weekly, then monthly. Eventually the memories were all recorded (there were only eight months of them, after all) and I’d used up every metaphor for agony that I could think of. Slowly synapses began to reconnect and a new life started to emerge. When I returned to Ty Newydd a year later, it was with a potential new romance in mind. The year after that, my annual retreat signalled the end of that relationship. Having new love in my life had eased my loneliness but it hadn’t been the saviour I might have expected after all. In fact, falling in love again had unleashed whole new layers of grief and tipped me into something close to a breakdown. If I spent the first year of grief wallowing in a pit of despair, I spent the second year grappling to climb out of it, trying to navigate my way in a new world with no faith in my map or my compass and no hope that some guardian angel was working for my greater good. In the second year I battled with anxiety, depression and what I eventually realised was post-traumatic stress. It was a very hard journey. It was hard to trust again. It was hard to love again. And it was very hard to lose love again. In fact, all of it was hard.

I said it was difficult to know where the story began, but it was even harder to know where to end it. As a writer it is always a challenge to know when something is finished. There are always sentences that can be rearranged, paragraphs that can be cut, loose ends that can be tied up or left hanging. There are a multitude of ways in which a story can be told. A writer can change the viewpoint, alter the tense, start at the end, flash back to the beginning. Words, sentences and paragraphs rearrange the meaning, the reader’s experience dependent, to some extent, on the narrative that the author chooses to present. But this story is true and there is only so much I can do to it without losing its authenticity.

When I sat this April in my room at the centre by the sea thinking about how to construct my writing as memoir, I wondered at first whether I should begin the story from scratch and write a memoir with the benefit of hindsight. I could have chosen to write it from my vantage point two years on, looking down like a seagull on the turbulent waves of grief. But I chose not to. I chose not to because there is something visceral about the way I recorded my grief, moment by moment, and I didn’t want to smooth over those edges or wash away the pain. Though I know it makes for difficult reading, I also know that it is in seeing their anguish reflected that the grieving can feel companioned. And it is in reading about my resurrection that the grieving can find hope. (Rest assured, reader, the resurrection did happen.) In fact, it is mainly because of that resurrection that I chose not to start the story again. Because this is fact and not fiction, my life, not just my story, and though the writer in me may, given time, be able to find a better way to write the narrative, the human in me cannot live with this material any longer. The human is tired of looking backwards and of picking over carcasses. The human’s eyes are on fresh horizons.

So, where does the story end? Does a love story finish just because the hero dies? Or do the threads that bind two lives together continue beyond the grave, beyond the last page? Does grief really end two years, eight months and four days after a traumatic loss? Or does sadness echo through the days that follow, seeping like wet ink onto the blank pages of the future? Of course it does. In fact, though it gets easier to live with, grief shifts and changes like clouds in the sky and goes on, in some form, forever. This book focuses solely on the first year of loss because I want to keep the focus on my precious relationship with Paul and not because I want to give the illusion that grief is resolved after a year. Grief, like love, goes on for eternity. I realise now that I wouldn’t have it any other way.

A day with Beverley Ward – Wednesday 26th August 2015

(from Paul’s diary)

After a brief meeting with Ed and co, I met B after an interval of some years. The last time I met her was at a Free Radicals gig … small world!Anyway, we spoke, chatted, she offered to give me a lift to my house (we were in Baslow at the time). It was dark, she dropped me off. I said perhaps you would like to come and have a go at something. A date was arranged.

Fast forward, she arrives. I am strangely smitten with this intelligent, proudly beautiful woman who has undergone many emotional trials – bad husbands, poorly son, difficult father. We have a fun day. We make a poker. We talk a lot. We have much to say. She has brought some homemade flapjack – very healthy and delicious.

The day draws to an end but there is a brief moment, I think a possibility of something more. It passes. Nothing has happened.

Later we embrace. I am restrained in my hug. I am not fully open. She leaves.

Afterwards I ponder on the feelings I have and recall what was said, her behaviour and begin to analyse it all. Perhaps a mistake!My first thoughts are how I yearn for her completely, physically and emotionally but as my assessment of the situation becomes ever more forensic I realise she is out of my league and I am seized with a deadening emotion. I feel paralysed, weakened by the realisation IT CAN NEVER BE.

Next day is work. I am out of sorts. I realise I must turn the situation around and just think of it all as one lovely day with a lovely woman.

Spring

(April – May 2016)

if grief had a voice

I will write this story because it is all I can do.

If I were a painter I would splash my grief across the pavement.

If I were a singer, I would sing my love into the midnight sky.

But I am a writer. And so I write.

I will write because the focus on the words gives my mind something to do,

save for digging around in dark tunnels where there are no lights,

staring at clouds where there is no hint of silver.

I will write this story because I loved you and I want the world to know

that, at the end of life, there was love,

that at the end of life, love is all there is.

I will write this story because I want it recorded for all eternity

that once there was a man like you

and that he loved a woman like me

and that it was beautiful.

I will write this story because I want to preserve

every precious moment that we shared.

I will write this story because it is my story, and your story and our story.

In this story we can stay together, which is how you wanted it.

As a writer, I am all-powerful: your wish is my command.

I will write this story because it is a good story and a sad story

and a big story and a true story.

And I am a writer and I know a story when I see one

even when it is handed to me in the most abominable way.

I will write this story so that people who didn’t know you

can understand how special you were.

I will write this story so that people who did know you

might see a side of you that they missed.

I will write this story so that people might understand

why I am so very sad.

I will write this story so that people might know that sometimes,

sadness is what is. And that’s okay.

At times I thought by writing this story I could make sense of these events.

But I am wrong. I am not all-powerful after all.

Sometimes there is no sense to be made of things

and searching for meaning is what drives us mad.

Sometimes I will write because, in the writing,

I can forget for a moment that this isn’t a story.

That this was your life and my life.

That you are gone.

And that it ended, sometime in the first act.

But mostly I will write to remember.

Once upon a time the man I loved died

They say that a story should throw us into the centre of the action and start with a bang. And so I start with a body, the body of the man I loved – your dead body. Without that appalling scene, this story wouldn’t exist. And so here I am, standing in my pyjamas and dressing gown on your doorstep, staring at the dead body on your bed. It might seem surprising to some that I can see your bed from the doorstep, but those people don’t know yet that you are a surprising hero, a blacksmith who lives in a tiny shack in a field. Also a little odd that I am out here in my pyjamas with two male friends of yours whose acquaintance I have barely made. They’ve just bashed the door of this shack in with a fire extinguisher as if we are in some kind of crime drama and a voice is saying the words, ‘there’s Paul’.

Before they’ve had time to stop me, I am pushing past them into the darkness of the room where you sleep and there is a breath in time where I think you might actually be asleep now, in which I feel guilty for dragging your friends out here in the dark. But as soon as I am near enough to see your body properly, I know that you are dead. Either that or you have been abducted and someone has left another deformed body on your bed. Part of me wants to run to you and hold you but a larger part recoils in horror and I stay in the doorway, wanting to leave but unable to move. I stay just long enough to take a picture in my mind, a picture that I will never be able to erase.

Your head is black and purple in hue and swollen so that your features are distorted. You look like the elephant man, completely unrecognisable aside from your clothes, clothes from which you are bursting, your body inflated and leaking. Your hands are clenched, there is blood on the bed and the stench makes me want to retch. One thing I know for sure – this is a body but it is not you. You are gone.

Your friend calls an ambulance. Someone on the end of the line asks routine questions, trying to ascertain whether there is any hope of resuscitation. We all know there is not but they force him to touch your skin anyway and check for signs of life even though he is saying repeatedly, ‘he is definitely dead.’ And I just stand there listening to the word: dead. How can you be dead?

Afterwards, I stand on the veranda shaking until someone ushers me into a car where I sit, still shuddering, and stare into space. I don’t know how long I am there. At some point I see blue flashing lights moving up the long drive to the shack where you live (where you are dead), and sometime after that a policeman slides into the driver’s seat of the car and asks me questions that make me feel like a terrible girlfriend. You have been out of touch for three days and judging by the state you are in, you have been dead for all of them. I wonder with him how it can have taken me three days to raise the alarm. Was it just yesterday that I was out on a day trip with a friend? What was I thinking going out for the day when you were lying dead on your bed? If this is a crime drama then I assume that I am a suspect. So I try to justify myself, explaining that you don’t always answer your phone, that we don’t live together, that we don’t see each other every day because of my children. I tell him that I have been sending messages and calling for days but that you haven’t answered. I don’t tell him that I worried that you might be about to dump me, but I tell him about the notes that I left last night on your door and your van. I tell him that the lights were on but that I couldn’t get in. I don’t tell him that I was frightened and crying, banging on your door and shouting your name, pleading with you to talk to me.

He asks me what your mum’s name is and I feel even worse. I don’t know. I can tell him roughly where she lives because you once drove me past her house but I haven’t met your mum yet. We’ve only been seeing each other for eight months and we just haven’t found the time. I can tell him the first name of your sister but that is all I know. I don’t know where she lives. I could tell him so many things about you if he asked: your favourite songs, what kind of tree you would be if you were a tree, how you have changed my life, but I can’t tell him anything that he wants to know.

The policeman takes my number and eventually says that I am free to go. I wait for your friends and find myself browsing Facebook as if it is just a normal night except for the fact that I am sitting in a stranger’s car in my pyjamas at one in the morning having just seen your dead body. I see that a friend is up and I message her to tell her that you are dead. How can you be dead? She phones and I try to explain through my tears. She says that she will catch a train in the morning to be there.

Your friends drop me back at home and I stand in the kitchen wondering what to do now that you are dead. I go upstairs and climb into bed with my daughter because I need to be next to someone whose heart is beating. I hold her hand and lie awake for hours. I think about the last time that I saw her, standing at the top of the stairs as I told her that I needed to go out to look for a missing friend, that I was leaving her with a stranger, that I would be back soon. I am wondering how I will tell her in the morning that I found you but that you were dead. It is only three months since I told her that my mum, her Grandma, was dead. It is only a week since she met you for the first time and gave me her approval. It is too much.

I am thinking about the last time that I saw you with her, sending messages on paper lanterns to Hephaestus the blacksmith god and the last time that I saw you later that evening. How we hugged in the hall of my house as we always did. How I didn’t know that it would be the last time. How I told you that I loved you. How you said you loved me too.

I am wondering how on earth I am going to get up and get the children to school. I am thinking about you and every snapshot of our beautiful time together, time that is now over, snapshots that I will record later. I am remembering our last messages to each other, the new poem that I’d sent you and your last words to me, carried like lanterns to my phone: I love your poem, I love clouds and I love you. I am thinking that I couldn’t make this story up. I am wondering where your body has gone and thinking that I never even turned back to say goodbye. I am wondering if they have found your mum or your sister and what happens next. But mostly I am just lying there thinking that you are dead. How can you be dead?

I am wondering how it can all be over now. This is not the way the story should end. It is not the way the story should begin. But it is the way it happened.

Clouds

I collect raindrops like tears

store them up for years

in a muffling grey blanket

protection from the searing

rays of the sun.

And it has begun.

We break through, nose first

hold tight as stomachs lurch

and then the bright blue glide.

Glad to be alive

all below is candyfloss and cotton wool

and we long to be released

to bounce on tiptoe,

light as fairies or feathers

in a pillow fight

a delight of primary colours.

But we land in gloom

and the earth’s a dirty smudge

beneath a grey-white ceiling.

There is no meaning

no shapes, nor symbols, nor metaphors.

So bleak we cannot even see the clouds

for the sky.

Time passes by.

Rain falls, the ceiling breaks apart

shafts of sunlight warm the skin

illuminating everything.

Wind blows, clouds scud

like surf across the blue.

If only we knew

that it was there all along.

Clouds forming, moving, breaking

gone.

I am not the person that I used to be

I used to be a daughter, a partner. Within three months, I have lost two of my names. Now I am just a mother and a friend. I feel peripheral. Loved, no doubt, but not essential to anyone, aside from the children. I cling onto them. For them I must keep living.

‘You are everything to me,’ he said. I was his world, on his mind when he woke up and on his mind when he went to sleep. Even though we weren’t together every day, I mattered to him more than anyone else in the world. He wasn’t always on the end of my phone but he was the person I said goodnight to, the person I talked to about everything. He was my future.

Now I am on people’s minds, I know. I get through each day with a rota of friends who keep a check on me, who come round and let me talk, who offer their hugs and let me cry. But none of them can hold me like he did and they go back to their own families, hug their own partners and leave me alone in this wilderness.

I want to call my mum. She wouldn’t know what to say. She was never any good with emotions. But she would be there, an anchor to the past. I was an essential part of her world.

Now, I float above the world like an untethered balloon longing to dissolve into the clouds to be with him. I look down and wonder what they are doing, all these people who are still living their trivial little lives.

I do have one name left. He called me Beverley Writer. And so I write.

What they don’t know

What they don’t know is that, for me, it doesn’t go away. That grief doesn’t just surface when someone mentions his name, or when I see something that reminds me of him. Grief is with me constantly. I am clothed in grief, I wear it inside out.

They say it hits you in waves and they are right, but I am swimming in grief all day long and the waves pound over me in relentless succession. Sometimes they actually knock me out. Yesterday morning I stumbled and fell as I tried to perform the routine task of depositing my son at school.

When they try to speak to me and I do not reply, it is not because I am rude. It is because I cannot see their faces through the spray of those waves. Everything is blurred.

Or maybe I am rude too. Because I don’t give a damn. I don’t want to speak to anyone unless they are saying his name. I don’t want to know anything that isn’t him. I would rather turn around and swim back out to sea, treading water and battered by waves that keep me close to his memory.

The times we missed

I want to remember the first time that we met.

I want it to be etched onto my brain,

hammered in with a chisel,

imprinted by the giant machine that you hated to clean.

I want it to be part of me, like the years of grime,

silted into the grooved landscape of your hands.

I want it welded to my neurons.

But it isn’t there.

I remember you though, and the time,

spoke of you to my friend who encouraged me then

as she encouraged me later.

She knew what I was yet to learn,

that your iron was worth more than all the words

of the other suitors, the poets and tutors.

But I was enjoying my freedom, living my dream,

didn’t want to choose, afraid to lose.

There was no rush.

I must have been doing my MA.

Maybe I spoke of it to you.

Maybe that’s why you told me you were ‘impressed’ by me,

too impressed to get close.

Maybe you were recently out of that relationship,

the one your mum clearly had hopes for

though you told a different story.

She didn’t want children,

was too much for you.

Maybe you saw that potential in me too

when you took me in over the wooden table in Ed’s dining room.

Too clever.

Too much.

No rush.

Only once were we alone.

You came round to my home,

the one with the terracotta walls.

You put up iron coat hooks reclaimed from a station cloakroom.

You’d picked out the numbers in neat, white paint,

fine work for such big hands.

You charged other people but you gave me mine for free.

I can picture you standing at the top of my cellar steps,

wedged in with one leg a few stairs down,

grounded, anchored as you were,

drilling into my wall while I watched,

not quite seeing what was in front of me.

It wasn’t the best place for the hooks

but I didn’t have anywhere else to put them.

You were probably wondering why you were giving them for free

to someone who would shove them in a cupboard,

who didn’t even make you a cup of tea,

who barely made conversation though she had so much to say.

It was wham, bam, thank you man and you had gone.

The first moment that we missed.

Or maybe I was already with Chris.

Because, the next time, that’s what I remember,

sitting at Ed’s table with Chris by my side and you opposite.

You were talking about your work and I was enthralled,

aid ‘it must be therapeutic’,

probably imagining myself banging out my own incessant worries:

to stay or leave, that was the question going round and round my head.

(I should have left, of course, I know that now,

but we all know about hindsight and that’s not how the story went.)

You said you’d show me how to make a poker one day,

planted a seed that would grow years too late.

You took Chris down a tunnel on a job.

I stayed at home when I should have come

but I was always too scared of being trapped.

‘Lovely guy,’ he said and we carried on

like a broken record until it snapped

and stuttered and could play no more.

And I was alone.

The next time is certainly carved in stone,

or stained in my mind’s indelible ink.

Surrey Street on a summer’s day.

We were going the same way,

me on foot, you on a bike.

You were smarter than I’d ever seen you,

under some female influence,

wearing beige shorts, a blue and white checked shirt,

it was even ironed.

You pulled into the kerb and stopped to chat.

I told you about the break-up.

You told me that you hadn’t seen Ed for a while.

He was with someone new. And so were you.

You didn’t have time for a coffee just then

or perhaps you thought you’d better not.

Things were going well maybe, with the new one,

not the time to rock the boat.

We didn’t realise that we were barely afloat

and that this was it and one life is all we have.

Sometimes there isn’t time to catch up later.

Keep in touch, I said. But you never did.

And you cycled off to look

like a stranger in photos of remembrance,

that I only see now

when you are gone.

On souls and soulmates

I meet your family for the first time a few days after I discover your body. It is surreal to say the least. With all of us in shock, we skip the small talk and set about the important business of discussing coffins and writing notices to go into the local press.

‘How do you want to refer to Paul?’ your mum asks, trying to get the wording right for the newspaper. ‘Partner, boyfriend?’

She’s looking at me over her spectacles, fragments of paper scattered on nearby sofas and coffee tables. She is trying to make order from chaos by ticking things off on the handy ‘to do’ list that the funeral director has delivered. She is waiting for my answer, the silence punctuated only by the pulse of the oxygen pumping through the tubes that I tiptoed around as I entered, the tubes that are keeping her alive even though I know that she must want more than anything to die. It seems like a simple question but I don’t know the answer. I want someone to confer with. Actually, I want to confer with you but you are not here and it seems odd to ask if I can phone a friend. Anyway, which friend would I phone? No one really knew us together. Partner seems presumptuous when we weren’t even living together and boyfriend seems ridiculous; you were fifty-three and a giant of a man. It just doesn’t seem right. And suddenly I find myself speaking, before I have had time to censor myself.

‘Soulmate?’ I offer. ‘Does that sound silly?’

And your mum, bless her, says no she thinks soulmate is just fine. I already like your mum.

Every once or twice in a lifetime, two people come together and something magical happens. Biologists might try to explain it with talk of pheromones and procreative urges and psychologists might tell us that we are drawn to each other in order to replay some familial drama but, for most of us, at the point of falling in love, all rational thought goes out of the window. In fact, we feel so far from science, that we might actually have slipped through that window, or perhaps have gone even further and broken through some space-time continuum into a different dimension. Suddenly we exist in a new galaxy where we and the object of our affection are the only living things. We are twin stars on a collision course that has been predetermined by some unfathomable force. (As I said, science is irrelevant. This is how it feels.) Where once we thought we were the arbiters of our own fortunes, we are now inexplicably tossed on the waves of destiny, pawns on a cosmic chessboard, out of control. We don’t care if we mix our metaphors, we just know that there is a rightness to this connection and that we are meant to be together, even though we have no idea who meant it to happen or why. Things that were blurred come into focus. We see our best selves reflected in the other’s eyes. We have met our soulmate. This is how it was for us, even though we had no idea how we could make it work. We were discussing it right until the day you died.

In the aftermath of your death a few of your friends have taken the opportunity to tell me that they aren’t sure we could have made it in the long run. I want to punch those people. ‘You could never have lived with him,’ said one. ‘He was a slob,’ said another. I think they were trying to make me feel better. At least now that you have died, I can be spared the disappointment of finding that you squeeze the toothpaste from the wrong end. In fact, your erratic teeth-cleaning habits had already been a subject of negotiation. You had lived alone in a shack in a field for years and unconventional was too conventional a word for the way you lived. But both of us went into the relationship with our eyes wide open and what other people couldn’t see was the focus and recognition of those eyes. What we had was unique. It was special. It was beautiful. It was not of this world.

It was, though, a paradox. We were deeply in love and, for both of us, nothing had ever felt more right and yet logic told us it couldn’t make sense. I had two children who got me out of bed at seven in the morning and, left to your own devices, you would go to bed at two and get up in the afternoon. I’m hardly known for being house proud, but your messiness was on a scale unlike anything I had ever seen. Caring for a sick child had turned my life into a military operation, where you were disorganised and carefree. And yet, somehow it worked. And it didn’t just work, it worked beautifully. When we were together, it was simple and magical and irrefutably right. But when we went back to our respective lives, sometimes, especially at the beginning, doubt would set in. Two or three times you sent me panicky messages saying that you couldn’t envision yourself in my life, that our circumstances were too different, that it was doomed to fail. And then, one day, something changed. I wrote you a letter saying that I thought we had something special but that I needed to be able to trust you.

You wrote me a letter back saying that actually, now, you couldn’t imagine me not being in your life. You wrote:

‘After much soul searching, many tears, and wandering up and down the road talking to myself, sometimes, quite sternly, I know what I want beyond all doubt. I want you more than anything in the world.’

When something feels so right why shouldn’t it work? It might not be logical, but since when did logic have anything to do with love? I will never know now whether we could have made it in the long run but I know we were soulmates and I know we had a chance.

The scent of you

It has been a month and I still haven’t changed the sheets. If I shuffle over onto your side of the bed, lay my head where yours rested and pull the duvet tight around my mouth, there’s a tiny patch where I can still smell you, where you had your armpit. I was never sure I liked your smell and it used to annoy me that I had to change the sheets so often. Now I bury my nose into that spot and inhale deeply, as though I can keep some part of you in my nostrils for all eternity.

I am still sleeping with your fleeces. The brown-checked one that you bought on eBay recently, that neither of us really liked and the big, thick blue one I saw you in just the other week. You were coming from a job to meet me in the park, galloping round the path to meet me. A giant bear of a man, running with his arms open wide, with no care for who was watching. We were so excited to see each other that walking wasn’t fast enough. Turns out we should have run faster. I launched myself into your arms and you held me tight.

Now I hold tight to your memory in those fleeces. I pull them towards me and curl around them like I used to curl around you and sob into the fabric where I used to sob into your chest. ‘I’ve got you,’ you used to say. Not anymore. The smell in your house after you died was too strong and I had to wash them in an effort to erase the pungent scent of death, a smell that I will never forget. Beneath the scent of washing detergent, a hint of it remains, and beneath that stench, still a slight smell of you. I wish I could bottle it and wear it like perfume. But it’s just a memory now. One day I will have to wash the sheets. But not today. Not yet.

The alignment of stars

I guess everyone’s love story begins this way, with the ‘what ifs’. If I hadn’t gone out that night, if I hadn’t broken up with that girl, if I hadn’t been late for the tube… Looking back it seems like magic was at work, or chance or fate or luck. Whatever it is, it feels good and we weave it into the narrative that it was all meant to be and, sometimes, if we’re lucky, it is mythologized in a wedding speech and, if we’re even more blessed, we get to the end of our lives and it is validated by the fifty years of happy marriage that we shared. It was written in the stars. If we’re unlucky, we end up as ‘star-cross’d lovers’ sacrificed for the greater good at the end of the play. Hey ho. Destiny is a tricky customer.

But still, if he hadn’t left me broken-hearted that April, I wouldn’t even have been single that summer. I never thought there would be a silver-lining to that cloud. But there was. If I hadn’t seen you outside the gig two years previously, I wouldn’t have known that Ed was divorced. If Ed hadn’t got together with his new partner, he wouldn’t have been taking kids to school with my friends’ kids and she wouldn’t have mentioned him. And maybe I wouldn’t have gone searching for him on Facebook after 12 years.

If Ed hadn’t been working round the corner from my house that day. If I hadn’t bought my Bongo campervan. If he didn’t have a Bongo too. If I hadn’t rudely abandoned my friend in a cafe and rushed home for a cup of tea with him. If you hadn’t phoned while he was there. If Ed and his gang hadn’t been going for a walk near your house that evening. If the kids hadn’t been at their dad’s that night. If I hadn’t decided at the last minute to drive at 90 miles an hour to join them, at least partly in the hope that you would be there. If you hadn’t decided to meet us for a drink at the pub later. Maybe it would still have happened another way. But this is the way it happened. And the way it might just as easily never have happened.

It was a lovely walk. I nervously chatted to people I didn’t know about questions of life and love but I was mostly focused on the main question of whether you would come to the pub or not. It was touch and go until the last minute. The pub near your house was shut and we had to go to Baslow instead. You probably wouldn’t have bothered to walk that far just for a drink. You didn’t even like drinking and liked your own company more. I could hear you on the phone to Ed, could hear you wavering. I almost said what he said, that I’d come and fetch you, but that seemed ridiculously keen. But he fetched you and you came.

‘Blacksmith Paul!’ I said.

‘Beverley Ward!’ you said.

We hugged with the warmth of old friends reunited after fifteen years.

‘You look good,’ you said. ‘You’ve lost weight.’

Cue the same old story about the sick child and the allergies and how if you cut out dairy, gluten, eggs and sugar from your diet, you will lose weight as a side effect. You had lost weight too but I had no idea how much. It is only when I look at old photos now that I realise what had happened to you in those intervening years. Later, you would tell me that you had sat alone on a hillside at New Year wondering if there was any point in going on. If you hadn’t picked yourself up and lost all that weight, would we still have got together?

I made sure we sat side by side and we joined in the general chat. I wished everyone else would go away so that we could have a proper conversation. We had a little one, about my imminent camping trip to Matlock and the raft races you used to do there. You asked me to see if I could find you some gold. We bantered about Fool’s Gold and crocks at the end of the rainbow. We were already on another planet. I asked you how the blacksmithing was going, reminded you that you once said you would teach me to make a poker. You said you would.

As we were leaving the pub, Ed could see what was happening. He’d tried once before to get us together. He tried again now.

‘Are you giving Paul a lift home, Beverley?’

‘Would you like a ride in my Bongo, Blacksmith Paul?’ I asked.

‘You don’t get an offer like that every day,’ Ed said.

“I know! I’m taking it!’ you said and raced off in the direction of my new campervan.

You directed me in the blackness to the driveway up to your place, the driveway I have driven up more since you died than I did when you were alive. There was an air of anticipation, a feeling of hope. It was good to be alone together. I thought you might invite me in but you didn’t, though clearly you were thinking about it. ‘It’s not suitable for ladies,’ you said.

Instead, we exchanged numbers and said that we would meet up soon for poker making. My fingers were clumsy as I typed your name into my phone. Blacksmith Paul.

‘I want an interesting name,’ I said.

‘Bongo Bev,’ you said, smiling.

I laughed. We said goodnight. And I went off to Matlock in search of the gold at the end of the rainbow.

Grief is the thing with teeth

I come like a black cloud on a sunny day.

But I’m a cloud with teeth, big teeth –

all the better to eat you with, my dear.

I chew you up, grind your memories between molars,

hold you tight in my grip.

I tumble you on my tongue,

churn up all the what-ifs of your broken world

until you don’t know truth from lies,

up from down.

Sometimes, at night, I take my teeth out and

then I swallow you whole into the damp cavity of my blackness.

You like it then, you know you do.

It is safe there where pain is the truth,

the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

There you feel alive.

Just when you’re comfortable, settling in,

I spit you back out, still wet, to stumble blindly into sunlight.

I leave you numb with no compass in a foreign land,

frozen in the glare of another day.

Don’t worry. I will come again soon.

When you least expect me.

When you don’t want me.

I like to keep you on your toes.

The weight of grief

There is an image doing the rounds. It is of a sculpture of a body, a wire cage of stones, brought to its knees. And sometimes grief does feel like this. Heavy, like it could floor me right there in the middle of whatever I’m doing. Like my whole body is made of rocks that rub painfully together if I try to walk. The weight is too much and movement becomes impossible.

But mostly, it comes in waves, invisible waves that seem to bypass everyone else and target only me, knocking me over with their force, until I can’t breathe and all I can see is blackness. If there are stones, they are being hurled at my head.

If I were to make my own sculpture it would be of a broken pier falling into the sea. When I look back to the beach, that is where I see my parents and my past. They waved me off to make my own way in the world. In the distance there are the people who walked alongside me for a while but they took a different turning. They preferred to walk on the cliff path or stayed safely on the promenade. But you were walking alongside me and walking with me into the future and suddenly you are gone. And the walkway stops abruptly at the edge of an unforgiving sea and I am left screaming into the darkness. There is nothing to hold onto out there. There is no desert island to swim to. There is no boat to rescue me and the walkway behind me has crumbled. There is nowhere left to go. I feel completely lost and alone, unanchored with nothing in the distance to reach for.

Frantically, I search for something to build a future from, weaving sticks and seaweed together, hoping to make a raft. But it is futile because sticks remind me of you and seaweed reminds me of you and you have the string.

I need someone to hold onto, someone who can hold me through this pain and torment, someone who can make this bearable. But that person is gone. There is no harbour in your arms anymore. All is sea and darkness and yes, sometimes, the weight of rocks.

You are elemental now

I see you in rainbows.

I see you in clouds.

I see you in big skies and bright stars.

I see you in shafts of light and pouring rain.

You are elemental now.

You always were elemental.

Red. For the blood. That is all.

—

Yellow like the daffodils in the poem I wrote on our last weekend away together. The hopefulness in that poem is like a smack in the face now. It feels like some malevolent force was listening to all my talk of spring and newness and rebirth and decided to come with a cleaver and chop down all the daffodils and take you with them. Not for me, the optimism of yellow. The hope of spring.

Pink, like the fleece I wore in the photos you took. The one where I am all woodland sprite on an autumn walk, climbing down from a tree with that beaming smile that only you seemed to capture, that only you gave rise to. We went looking for a highwayman’s cave. Never found it but didn’t care. Instead we found a patch of grass on a hillside and called it home. We lay down and watched the sun slowly slip out of the sky. A priceless moment, bathed in the pink light of dusk, perched on the edge of love.

There was so much green. Green fields around your house on the day we first sat together on your porch. Green grass in the park as we walked the dog. Green trees on woodland walks. Even though we mostly loved in winter, we lived in green on those magical days. Now I am green. Sick with horror, and green with envy for the people who loved you for longer than I did and the people who hold their loved ones close at night. Green is sprouting out all over now, like a reminder of a love that was just beginning to truly blossom. A love that will never ever see the summer.

Purple for the heather on that first September walk we took together. The joy of boundless discovery, rampaging across the moors, conversation never faltering, being completely present and yet aware that there was just the faintest purple tinge of forever in the air. There has never been a more perfect day. I’m so glad I spent it with you. I’m so sad that we will never do it again.

Orange for a man of fire. The flames of the bonfire you built for me on New Year’s Eve. You carried the wood and an axe up the hill, breathed life into sticks just as you breathed life in to me. Sitting between your legs, feeling my shins burning, watching fireworks exploding over the city that was home to both of us for our whole lives, lives which were spent at less than half a degree of separation until last year. Flames of passion burning bright. Snuffed out, without warning, overnight.