Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Lola Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

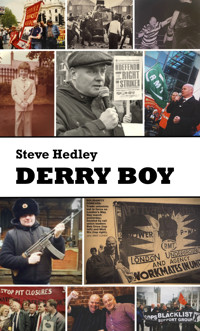

Described by the right-wing media as "the most dangerous man in Britain" because of his uncompromising socialist views, Steve Hedley, born in Derry (Ireland), tells the story of a massacre in his hometown and other significant events that shaped his ideology. Steve shares his memories of the hunger strikes, the poll tax, his participation in militant antifascism and trade unionism which led him to be elected to second in command of the RMT union. He explores the limitations of trade unionism and advocates a return to class politics tied to environmental and global socialist goals. This is an exciting thought-provoking book which sparks a debate about the state of the left in Britain and the necessity of employing the power of the working class to combat catastrophic climate change and war.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 327

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Steve Hedley

DERRY BOY

Copyright © Lola Books 2024

www.lolabooks.eu

This work, including all its parts, is protected by copyright and may not be reproduced in any form or processed, duplicated, or distributed using electronic systems without the written permission of the publisher.

Printed in Spain by Safekat S.L., Madrid

ISBN 978-3-944203-70-6

eISBN 978-3-944203-80-5

Original edition 2024

CONTENTS

SYNOPSIS

FOREWORD

1 BOGSIDE “BRED”

2 PLANET OF THE IRPS

3 DOING THE BOXER BEAT AND MEETING GIRLS

4 LONDON CALLING

5 I’M A UNION MAN I’M PROUD OF WHAT I AM

6 LEFT FIELD OR LEFT OUT?

7 STEVIE USED TO WORK ON THE TRAINS

8 ALL CHANGED, CHANGED UTTERLY

9 IT WASN’T COOL TO BE UCATT

10 DRINK PROBLEM? I DRINK, NO PROBLEM

11 BACK ON THE CHAIN GANG

12 THE SPY WHO GRASSED ME

13 BLACKLISTED BY THE BOSSES AND THE SPY COPS

14 GOING UNDERGROUND

15 THE INFLUENTIAL “UNDERGROUND CELTIC SUPPORTERS CLUB”

16 NEW LABOUR ISN’T WORKING

17 TAKING ON THE EDL

18 THE FINANCIAL CRISIS

19 FINALLY, AT LEAST AN APOLOGY, IN PART AT LEAST, FOR THE BLOODY SUNDAY MASSACRE 38 YEARS AFTER THE EVENT

20 BEEN WORKING SO HARD

21 ACCUSED OF BEING AN ANTISEMITE BEFORE SUCH ABUSE BECAME FASHIONABLE

22 UNLUCKY FOR SOME 2013

23 A “FRIENDLY” AT CLAPTON

24 THE WORKING-CLASS LOSES ITS LEADER. THE KING IS DEAD

25 TIME TO CASH IN

26 OH JEREMY CORBYN/OH NO JEREMY CORBYN

27 SUDDENLY I WAS A SENIOR AND IN THE MIDDLE OF A FAMILY FEUD

28 THE PHONEY WAR GETS REAL

29 CASH BACK

30 MADAME PRESIDENT

31 COVID KILLS OFF ANY LINGERING PRETENCE THAT CASH OR LYNCH IS LEFT-WING

32 BORIS JOHNSON AND HIS PART IN MY DOWNFALL

33 I AM SUSPENDED

34 THE GENERAL SECRETARY ELECTION

35 THE RMT “BROAD LEFT” AND THE ELECTION OF ALEX GORDON AS RMT PRESIDENT

36 PETRIT MIHAJ IS SACKED, AND THE ENTIRE RMT LEADERSHIP CROSS HIS PICKET LINE

37 I RETIRE FROM THE RMT

38 THE WORKERS STRIKE BACK

39 “REPUBLICANS” LOSE THE MOMENTUM BY CALLING OFF STRIKES FOR THE MONARCHY

40 THE RMT LEADERS AGREE A BELOW INFLATION DEAL FOR NETWORK RAIL AND LEAVE THE TOC MEMBERS TO FIGHT ALONE

41 THE PERIOD 2022-2023: A WASTED OPPORTUNITY

42 CAN WE FIX IT? YES, WE CAN

43 CAPITALISM ISN’T WORKING

44 SYSTEM CHANGE NOT CLIMATE CHANGE

45 DON’T MENTION THE WAR

46 A PLAN OF ACTION

47 YOU THOUGHT IT WAS ALL OVER, WELL IT IS NOW

SYNOPSIS

I have been called “the most dangerous man in Britain” by right-wing commentators because of my political views. An uncompromising trade unionist and socialist, I acknowledged that our society was based on the exploitation of my class, the working-class. I did not start the class war which is as old as society itself but consciously took part in every battle and skirmish I could. Why would an Irish immigrant, whose people were brutalised and murdered by the British state, spend most of his life fighting for the working class in Britain? This book hopefully answers that question.

The book begins with one of my first memories, which was my Granny swearing during the Bloody Sunday massacre. It continues through my childhood where citizens of my hometown Derry, set up autonomous zones outside the control of the British state. I explain how my politics were formed by acts of barbarity from Britain including collusion with loyalist terrorists and allowing 10 young men to starve to death. I explain the effects that the heroism of the hunger strikers had on me and a generation of my peers and how this has shaped Irish politics ever since.

I trace my political development from meeting striking miners in Ireland to being forced to emigrate to England and taking part in momentous events there from opposition to the Poll tax and Iraq war, and resisting fascism on the streets, to becoming second in command of one of the most powerful trade unions in Britain the RMT. I explore the role of unions, their strengths and limitations and reach the conclusion that without conscious revolutionary leaderships, Unions with right wing or reformist leaderships only perpetuate the capitalist system and their leaders are indeed “the loyal lieutenants of capitalism”.

I explain the consequences of being an effective trade unionist and how I was blacklisted, spending a year out of work because the bosses and political police (Special Demonstration Squad) conspired to keep me unemployed.

I explore some of the events and debates in the RMT union especially around the Covid period and after. The decisions taken by the leadership were in my view disastrous and have led the union on an increasingly right-wing trajectory, encapsulated by the entire union leadership crossing the picket line of a worker they had sacked.

Faced with climate catastrophe and war, both of which are inevitable parts of capitalist competition to capture markets and generate more profit from the exploitation of workers worldwide, I attempt an analysis of how catastrophe is imminent if we continue on our current path, and offer an alternative vision. I advocate a realignment of the left by abandoning identity politics and concentrating on issues that unite the working class such as economic beneficial, climate friendly jobs. Time is running out for great swathes of humanity; the working class and poor are suffering disproportionately from climate change and will pay with our lives if we don’t force a change in policy. Finally, this book ends on a call to arms of all who are exploited by capitalism to come together and effect change, only we the working class have the material need to avoid millions of deaths, as they will be our deaths. Only we can be our own saviours, but time is short, and we need to act now.

FOREWORD

This book is a series of memories and reflections upon current events. Memories can change over time. It is not meant to, nor can it be a comprehensive account of all that has taken place in my lifetime. It is merely what has stuck in my mind and my attempted analysis of these events. I also needed to write down what I think some of the solutions may be, as I don’t think that up until this point I have read anything most working-class people can relate to, and in my own small way I want to help remedy this. I have tried to be as honest as I could be about how I felt at different times in my life, and feelings also change over time, so if what I’ve written offends you, I can only say “get over yourself”. As someone told me when I first criticised a union rep, if you think you can do better then throw your hat in the ring, so feel free to write your own account, offer your own solutions, it will most likely enrich the whole debate and if you can’t do any better, you’ll be comforted to know yow will struggle to do any worse. Finally, I must thank all my daughters and my ex-wife Julie for encouraging me to write this book and Iona Burnell Reilly for reading it and giving me some very good advice along the way. I hope you, the reader, are challenged by my writing, and hope that it causes you at least to think critically and question everything that you’ve been told.

DERRY BOY

1 BOGSIDE “BRED”

People were crowding into my Granny’s hallway wearing handkerchiefs over their faces to protect from the CS gas which stung the eyes and choked every man, woman and child in the Bogside. I could smell the terror, people were screaming and panicking, crying uncontrollably and then the unimaginable happened and my Granny swore. Those words are seared into my mind “Jesus Christ, the bastards”. I was gobsmacked: Granny Mc Laughlin never swore, she was always scolding people who swore, including my Granda who would push the envelope and say “buck” when he had the backing of a few Guinnesses. Granny was a staunch Catholic and had that old-school, working-class sense of respectability, demanding we all say the rosary every night and never ever swearing. This was strange indeed. The living room became packed as people gathered around the Radio Rentals black and white TV, jostling to get a view of the latest reports of the atrocity. It seemed every few minutes more people were being reported murdered by the British army as the world’s media gathered in Derry that day to report on a civil rights march. The Brits couldn’t cover this up like they had Ballymurphy or several other massacres of civilians; “Bloody Sunday” as it became known was broadcast across the world exposing the vicious brutality of the murderous British state for all to see. I was three and a half years old, and this was one of my earliest memories.

I lived in Creggan about ten minutes’ walk from Granny’s and already hated the Brits. They killed my budgie by firing CS gas indiscriminately into the flats where we lived. In retrospect, their actions were pure counterproductive sadism, they achieved nothing but to engender more hatred. They stopped people in the street and humiliated them, sometimes beating them, sometimes arresting and torturing them for weeks and months at a time. Night-time raids were frequent as people were turfed out of bed in the early hours, their houses ransacked, furniture smashed, property stolen and if there were any young men in the house, arrests and subsequent beatings frequently took place. We hated them, the whole community hated them, and they hated us back.

Shortly after Bloody Sunday, we moved to Tyrconnell street two doors away from Granny’s and with the other kids or wains as we were known I often stood guard at the barricade at the top of the street, which was meant to keep the army out of “Free Derry”, the autonomous zone that had sprung up after the battle of the Bogside. When army Landrovers and pigs made incursions into our area we threw stones, bottles, and anything else we could get our hands on, this was often accompanied by the cacophony of women banging bin lids to alert IRA volunteers, who we idolised as our only protectors, that the Brits were about.

These were heady times, the Catholic population of the Bogside and the whole of the occupied six counties of Ireland had risen up after over forty years of oppression, discrimination in jobs, housing and even voting rights. Inspired by the Civil Rights movement in the United States, young activists like Bernadette Devlin and Eamonn McCann with their comrades in people’s democracy had effectively broken the stranglehold of the ultra-conservative Nationalist party, with their brand of Marxism based on empowering the community and self-organisation. The orange state had reacted to peaceful protest by attempting to, quite literally, beat people into submission, with the sectarian police force and orange mobs setting upon the mainly student contingents: Mere girls and boys who dared protest institutional anti-Irish racism were beaten to a pulp.

It is worth giving a whistle stop tour of Irish history to understand how we got to this situation where Catholics and progressives were systemically discriminated against and beaten off the streets for the most reasonable demands. “British rights for British citizens”, yes, seriously that was one of the demands of the Civil Rights movement.

Ireland’s English problem began in the 12th century with the Norman Invasion, which initiated centuries of Irish resistance to rule from England and resulted in Irish rule throughout most of the country, except an area around Dublin known as the Pale. In 1541 Henry 8th declared himself King of Ireland. In order to maintain control, Henry initiated a plantation of English settlers in Irelands. Irish people were dispossessed of their lands, and this was given to the settlers.

King James 1st led a far larger plantation in Ulster, which was by far the most rebellious province, by bringing in thousands of Protestant settlers from Scotland and England between 1606 and 1609, forcefully taking the best land away from Catholics and giving it to the newcomers. This ensured that the settlers who had benefited by the immiseration of the native population, and divided from them by religious difference, would be loyal to the crown in order to maintain their stolen lands and privileges.

Resistance continued and Oliver Cromwell invaded Ireland between 1649 and 1651, driving Catholics out of Ulster, Munster and Leinster, and banishing them to Connaught on pain of death. “To hell or Connaught” was not a slogan but a terrifying reality for Irish Catholics. The Penal laws outlawed Catholic priests and clergy and forbade Catholics from higher education, professions and owning land. By 1778 Catholics held only around 5% of the land in Ireland.

In 1789, Theobald Wolfe Tone, one of the leaders of the United Irishmen, the fathers of Irish Republicanism, who were almost exclusively Protestant, led a rebellion to end British rule.

The Famine (1845–1851) saw the genocide of Irish people, mainly Catholics, with 2 million starving to death or forced to flee the country whilst the English were helping themselves to thousands of tonnes of Irish grain and massive amounts of cattle and other livestock. Various other rebellions took place, all unsuccessful, with Irish resistance vacillating between armed resistance and constitutional parliamentarianism.

The 1916 Easter Rising and the subsequent murder of its leaders saw nationalist sympathies multiply to such an extent that in 1918 Sinn Fein won the vast majority of parliamentary seats in Ireland. The years 1919 to 1921 saw the Irish Republican Army wage a War of Independence. This led to the Anglo-Irish treaty of 1921 which saw the Irish Free State emerge in 26 counties, while Northern opted out. The Free State became the Republic of Ireland in the 1940s and was formally recognized by the United Nations.

From its inception Northern Ireland was to be “a Protestant state for a Protestant people”. Its institutionalized discrimination against Catholics, was designed deliberately and transparently to protect Protestant supremacy. The choice of a six county statelet with an inbuilt Protestant majority was meant to ensure unchallenged domination for generations. It also engendered a siege mentality where paranoia was fed to gain political advantage for ambitious politicians.

Easter 1966 was the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising of 1916 which ultimately led to 26 counties of Ireland gaining their freedom from British rule. The commemorations were very much a peaceful affair celebrated with parades and marches. One exception was the blowing up of a statue of Admiral Nelson in Dublin. The IRA was in mothballs after a disastrous border campaign in the 1950s and posed no military threat to Britain. This did not prevent unionist paranoia growing, given voice by the demagogic Reverend Ian Paisley, a Protestant bigot who was virulently anti-Catholic. Paisley and other extremists set up the Ulster Constitution Defence Committee (UCDC) which had a paramilitary wing, the Ulster Protestant Volunteers (UPV), to defend Protestant supremacy.

Paisley distrusted the Northern Ireland Premier, Terrence O’Neill, whose views he deemed far too liberal. Paisley and his acolytes’ wild rhetoric had really appalling consequences as a new Loyalist terrorist group styling itself as the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF, after an organisation created in 1912 to oppose Home Rule) was founded in the staunchly loyalist Shankill road in Belfast. The UVF was led by Gusty Spence, an ex British soldier, and although it was relatively small, many of its members were also part of Paisley’s UPV. The UVF unleashed a campaign of terror against Catholics, burning down houses, businesses, and even Catholic schools. A UVF petrol bomb attack killed an elderly Protestant lady, Matilda Gould. The terrorist attacks escalated with the murder of John Scullion, a Catholic who had no political connections. The murderous sectarian atrocities continued with three Catholics shot by the UVF as they came out of a pub, one of them, Peter Ward, being murdered in the process. The UVF were banned in Britain and Ireland after this cowardly murder.

At the same time the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association were campaigning to end discrimination against Catholics in jobs, housing and voting and to reform the sectarian RUC, a police force that was less than 10% Catholic, and routinely brutalised the Catholic community using the Special Powers Act to jail people without crime or trial.

Protestant politicians explicitly wanted to preserve Protestant privilege and their paranoia was inflamed by NICRA who they saw as a Republican front. Some Republicans were NICRA members, but they were small numerically in the organisation and not influential in its decision making.

An important event occurred on 24th August 1968, when UPV members attacked a NICRA march from Coalisland that was attempting to go to Dungannon. Police watched on as marchers were badly beaten with cudgels by the loyalist thugs, this spectacle was to be repeated many more times that year. A Civil Rights march in Derry on 5th October, was banned by the government, and when protesters assembled anyway, the RUC beat them mercilessly with batons injuring 100 people which included many high-profile nationalist politicians. This was caught on camera, broadcast on the news, and sparked serious rioting in Derry.

Terrence O’Neill, in an effort to avert more trouble and sensing the very bad international publicity his government was getting, promised the Civil Rights movement concessions. On 1st January 1969, People’s Democracy, a small Trotskyist organisation started a march from Belfast to Derry. When the demonstration got to Burntollet Bridge, loyalists, including some off-duty RUC men armed with iron bars, bricks, cudgels and bottles, launched a vicious attack. Despite being badly beaten the marchers continued to Derry where again they were attacked by loyalist thugs. The RUC then began a pogrom in Derry’s Bogside attacking people indiscriminately and ransacking Catholic homes. The community defended itself, setting up defence committees, using petrol bombs and barricades to stop the police terrorising them and setting up “no go areas” where the forces of the state could not enter. Loyalists even bombed water and electricity plants in 1969, blaming the IRA and the Civil Rights movement, to get support for their own cause.

In April 1969, the Loyalists and police attacked civil rights marchers in Derry, and the RUC smashed into the house of Samuel Devenny beating him and his family, leaving his teenage daughter unconscious. Samuel died on 17th July from his injuries. On 13th July, RUC officers murdered another Catholic, Francis McCloskey, in Dungiven, beating him so badly that he died the next day.

The major clash, which was to have lasting repercussions began on 12th August, the battle of the Bogside lasted for three days when local youths fought off loyalist and paramilitary police attempts to launch another pogrom against the Catholic area. Triumphalist sectarian marching bands and their supporters backed by their brethren in the police were fought off by the heroic Derry people who defended their community. The police lost control of the situation and the Catholic community were victorious. Belfast and other Catholic areas began rioting in sympathy with Derry and to draw away the crown forces from the city. Loyalists responded by launching their own pogroms against Catholics in Belfast, burning down whole streets of Catholic houses. What remained of the IRA attempted to defend against the attacks with a few antique weapons. Police murdered a nine-year-old boy named Patrick Rooney, shooting him dead when they inevitably took the side of Protestant mobs against the Catholic victims.

Thing had gotten so serious that the 26-county Prime Minister, Jack Lynch, called for United Nations intervention, condemned RUC brutality, and set up a refugee camp just across the border from Derry in Donegal. He even threatened a humanitarian intervention using Irish troops if Catholics were left unprotected. The injuries of the state terror mounted, 10 people had been murdered, people had been killed, over 700 injured, including 154 by shooting. Hundreds of homes had been so badly damaged that they had to be demolished. 1,505 Catholic and 315 Protestant families were forced to leave their homes. The state responded by launching Operation Banner, sending in masses of British troops on 14–15thAugust. These were initially welcomed by most nationalists, before they turned on the community and became another force to oppress Catholics. A barbed wire fence was constructed between the Protestant Shankhill and Catholic Falls areas of Belfast. This was to become the Peace Wall which still exists nearly 3 decades after the Good Friday agreement. Even the British state could not ignore the sectarian RUC’s role in the riots. The Hunt committee eventually concluded that the RUC should be disarmed, and the B Specials abolished. The only policeman killed was shot by the loyalist UVF.

For a brief time, Derry’s people ran their own affairs (1969-72). The police, the army and to some extent the state was forbidden to enter Catholic areas. Having failed to defeat the risen people in the Battle of the Bogside (12th-14th August 1969), when orange mobs celebrating the lifting of the siege of Derry attempted to conduct a pogrom in the Catholic Bogside area, and were supported in doing so by their brethren in the police and notoriously anti-Catholic B specials, the orange state had to concede defeat, at least temporarily. In the end the forces of the state were fought to a standstill by the local youth who poured petrol bombs, bricks, and rubble down on their heads from the commanding heights of Rossville flats.

Free Derry was world famous, and obviously the threat of good example could not be tolerated by the British state. I often wonder if the Brit government knew exactly what they were doing on Bloody Sunday, fully understanding that the cold-blooded murder of 14 civilians, and the shooting of 12 more who survived, would swell the ranks of the IRA, but knowing that ultimately any guerrilla army could not defeat the British state and its loyalist murder squads and would at some point seek compromise. This although a risky strategy for the Brit government, fraught with sectarian murder and near civil war, was none the less preferable to the Brits than a real revolutionary situation developing where citizens committees ran their own affairs. I mean if Derry could do it why not, Belfast, Glasgow, Liverpool, Birmingham, or Leeds? Yes, I’m suggesting that there was the real possibility of the government taking a decision that would instigate a 30-year sectarian bloodbath rather than leave the door open to any kind of socialist politics. The massacre itself was whitewashed for 30 years and the commanding officer responsible for this atrocity, Colonel Derek Wilford, was given an OBE.

Our street and indeed our house was a hotbed for debate. The IRA had split into two factions in 1969. The socialist, Official IRA, who in broad terms saw themselves as the defenders of the Irish working class and heirs to the 1916 Republic, and the Provisional IRA, who were much more nationalist and militarist and could be described as the defenders of Catholic communities. My family were initially very sympathetic to the officials or “stickies” as they were known (the name came from them selling Easter lilly badges with sticky backs as opposed to the Provo lilies which were held on with a pin). The overt Marxism of the officials did not play well with the Free State government, made up of Fianna Fail who shared their hatred of socialism with their even more conservative opposition, Fine Gael. The Irish American diaspora of course didn’t much like reds either and wanted a bit of good old-fashioned militarist revenge, hence the massive funding for the Provos and the fact that the Officials scaled back and eventually abandoned their armed struggle, enabling the Provisionals to become the dominant force all over the occupied six counties within a few years.

The Brits made me an enemy for life when they personalised the conflict by shooting my pet border collie Terry, claiming that they thought he was a sniper and leaving him for dead in the lane a few doors above our house, nearly adding him to our own dead pet role of honour, headed by my gassed budgie. What had the bastards got against harmless animals? For good measure they had also nearly shot me and my brother Keith as we played cowboys in the lane a few months later; we were aged 4 and 2 respectively and, obviously part of the renowned and feared IRA midget brigade, armed with a wooden sticks, cowboy hats, and sheriff badges, we were legitimate targets in the well-trained eyes of the Brit occupiers. Me, Keith, later our cousin John and our friends Longo (John Long), Blackie (John Black), the Dohertys (Jackie and Martin), and the Dorans (Kieran and Gary) all played our part in fighting for Irish freedom by stoning the brits whenever they appeared, and calling them all sorts of swear words none of which any of us understood. I can honestly say we had no fear of the Brits, but were absolutely terrified of our mothers or “Mas” as we called them, finding out what we were up to, and were always wary of touts.

Our safe havens were Dorans, where rebel music was always on the record player, telling us of the heroes who had died for Ireland, and Longs, whose dad made ornaments from plaster moulds, and we would steal the paint and put it into bottles to throw at the crown forces. Green paint was our favourite, as we somehow believed that this would wind the Brits up more. We would hide in the grass in Celtic Park and hurl our paint bombs at the passing army vehicles shouting, “Up the Provos” and “Fuck off back to England”. Now I’m not advocating a return to these activities, but all this rioting exercise meant that there was no child obesity crisis in the 1970s. Sometimes we’d even phone the police from a phone box just to throw things at them when they arrived, it’s a wonder we weren’t all shot.

It is crazy now to think that children born into conflict just regard it as normality. We all cheered on the IRA although we had no idea what the struggle was about except that we were the good guys, and the Brits were bad, as they had stolen our country. We all saw and heard bombs go off, participated in riots, sometimes for recreation, were stopped and searched on a daily basis at army check points if we wanted to go to school or the town centre. We all had our houses raided, had neighbours, friends and even family arrested and tortured for no reason, other than they were Catholic, and to us this was just the way the world was. It was a shock to me when I first visited England that people there had so much freedom compared to us, but later I was to learn that this in itself was somewhat illusory.

Keith and I attended St Eugene’s school which rudely interrupted our patrolling of the street’s barricade. The educational authorities were obviously aware of our revolutionary potential and decided to incarcerate us all day in the hands of the some of the most ruthless counter revolutionary elements in Ireland, the nuns. The school was run by nuns but also had civilian teachers who were equally classist, snobby and sadistic. I did well at school because the nuns at the orphanage where I was adopted blagged my adoptive parents that my dad was a doctor (it turned out he was a brickies labourer). Therefore, it was expected that I was going to be intelligent, was encouraged to be so and to a certain extent this became a self-fulfilling prophecy, all be it based on porkies told by nuns. My brother didn’t have such a creative nun on hand to embellish his credentials and therefore the expectations of him were I think lower, which is a real pity as he’s one of the smartest men I know.

Our activism wasn’t completely dead: at weekends we would torment the “peace woman” a member of a group opposed to violence in our street by kicking her door and shouting “soldier doll” through her letterbox. My uncle who lived with Granny two doors away had nicknamed her Tonga, after the obese queen of Tonga, and this was quickly added to our repertoire of taunts. This all came to a sudden end when Ma was informed of our subterfuge, and we got battered senseless and threatened with a priest. To be fair the paedo scandal had not yet broken, but looking back that was a bloody sinister threat. I never forgave the peace people for my beating and now had proof of them being touts. When “Tonga’s” car was torched, there was a debate if it was the IRA or an insurance job as the next one was far newer and smarter looking, my money was definitely on the latter.

My mum liked a drink, as did most of our family, and would be out to “Bingo” most nights, obviously getting lost along the way home and ending up in the pub for hours, coming home pissed. She and her smoking partner, my aunt Philomena, were liberated women before it came into vogue. I have a confession to make, and that terrible secret is that my adoptive dad was English, he was a complete bastard, and therefore was in no capacity a deterrent to my hatred for the other English bastards occupying our country. Why he tolerated Mum’s behaviour was a mystery. He was ex-navy, an electrician by trade who ended up working for the Swilley buses as an engineer, until he had an accident and became disabled. All this drinking scandalised the ultra-Catholic neighbourhood that we lived in, and no doubt we were the butt of a lot of the gossip, deserved or undeserved. The fact that my adoptive Dad was English obviously raised suspicions although he always professed his “socialism” (in reality, Old Labour welfare capitalism) and his support for Irish independence. I think at least his labourism may have been genuine.

Kids in those days were numerous with families of six or more very common. This meant that each street had gangs of kids who would often fight with the next street along. Our main enemies were from Limewood street, the next street along from us, and battles would commence in the lane between the streets until someone was hit with a brick or an adult appeared and gave chase to us. Fights would take on added importance when the 15th of August, the anniversary of internment came around and each street would build a bonfire and other streets would attempt to steal it or “raid” it as we termed it back then. It’s incredible to think now that adults encouraged and attended these bonfires usually stacked against the side of somebody’s wall and full of tyres that gave off dense choking black smoke. Despite the obvious dangers, I would say my childhood was good, I was quite studious, enjoyed reading, especially Marvel comics, and as we had only two children in the household, we got lots of toys and new clothes, usually from Freeman’s catalogue which my Dad ran until most of his customers knocked him. Despite several threatening letters from Freemans, they never did have the bottle to come into the Bogside and try to get their things back, which is just as well as their goods may well have been liberated and their van hijacked as an example to other capitalist predators.

We left the Bogside when I was about 10, lured by the promise of an inside bathroom in a new house in the Galliagh area about three miles from our previous abode. I remember the day we left, my Granny was distraught, it was as if we were emigrating to Australia rather than a 15-minute drive away. All the neighbours turned out to wave my Ma goodbye, some probably secretly relishing the fact that she’d fallen from grace in moving to a council house and away from their privately owned street. My Dad probably saw it as a chance to separate mum from the other drinkers and her partner in crime Philomena, in particular. As it turned out, this wasn’t an altogether unsuccessful strategy as her drinking was largely restricted to the house from then on with just the occasional foray to “the Bingo” on special occasions.

2 PLANET OF THE IRPS

Having moved to Galliagh we settled in and made friends in our “square” which was how the houses were arranged. Our neighbours on one side were Sinn Feiners and on the other side, members of the IRSP (Irish Republican Socialist Party), who had split away from the Official IRA when the latter abandoned the armed struggle. This inevitably led to increased surveillance and raids on our house. Galliagh, for reasons of which I am unsure, had a large contingent of IRSP supporters, which led to detractors labelling it “planet of the irps” (pronounced Urps.) The next couple of years passed quietly as I completed my last two years of primary school and was recruited into being an altar boy at the local church, St Joseph’s. I think Jesus must’ve been as surprised as I was at this turn of events, although he never mentioned his misgivings to me once. I went to the local Slievemore school, where my brother Keith was outclassing me in naughtiness, flooding the toilets and even being held captive in a police van after they caught him running away after he’d thrown a brick at it. This made him incredibly popular especially with girls just as I was developing into a boring goody goody swot.

Like most schools in Derry, my primary school was a Catholic school, and the children were exclusively from a Catholic background. Reflecting on this in later life I had grave concerns. Derry unlike Belfast had quite clear dividing lines, most areas by this time had either a vast majority of Catholic residents or a vast majority of Protestants. Galliagh was a Catholic area, so every child there was drawn from the surrounding area and was Catholic. In secondary education things were a bit different, the three main secondary schools were miles away from the districts where most pupils lived, and this forced a commute of around three miles every day. That said, the secondary schools were again exclusively Catholic, and this made no sense except to perpetuate the power and influence of the church. If people had to travel anyway then it would seem logical to have schools of mixed religion or of none. I don’t want to exaggerate the potential effect that this would have had socially and politically, but I think mixing with kids from other religions would inevitably have led to friendships, which may have helped dispel myths and eventually have helped break down the sectarian divide. Most of my school mates would never have met a Protestant at school for their entire educational period and the same could be said for Protestant kids, who would never have met a Catholic. Even after nearly 30 years of the peace process, the divisions in education still remain. The main reason for sectarianism is the British occupation of the Northern six counties of Ireland, because the British nurtured and encouraged religious strife, in order to divide, conquer and rule the inhabitants of the North. If that division is to be broken down, however, a good starting place is the education system. The fact that this hasn’t happened is partly because of the communitarian structure of politics in the North, where every major political party draws its support from either the Catholic or Protestant communities, so that it therefore in the parties’ interests to maintain the segregation. Only In 143 from 1,000 schools in the North was there at least 10% of pupils from both Protestant and Catholic communities. 287 schools had either no Catholics or no Protestants.

Our house in Galliagh was opposite farmers’ fields, which led onto a mountain trail in those days, and we spent the summer holidays either hiking for hours at a time or riding our bikes out early in the morning and returning about 9 or even 10 pm, as the daylight lasts longer in the North. We hung out with gangs of kids, often three or four from the same family, with the McDevits, Lynches, Wallaces and Hanleys, being our closest friends, but also with many other kids in the area too. This was before video games and fear of strangers limited the freedom of children.

I gained a scholarship to the local Grammar school, St Columb’s college (or seminary for young priests, to give it its full title, I can only imagine that they called it that for tax reasons). I hated every minute I spent in that institution. They were on a mission to create a Catholic middle class and disliked working-class pupils interfering by gaining entry there. They discouraged pupils from mixing with kids from more working-class schools, even though in many cases pupils had siblings at these schools. I was a case in point, as my brother Keith went to St Peter’s, a secondary school in the Cregan area. Most of the teachers at St Columb’s were appalling, the majority hit the kids with leather straps for any perceived infringement, with the Latin teacher, McGinty, revelling in his sadism and simultaneously taking money from working-class people who couldn’t afford it in his role as part shareholder in a bookies shop. Rumours of teachers abusing boys sexually were also rife, and at least two of those most suspected were dismissed from the school shortly after I was expelled, near the end of 5th year just before my “O” levels.