16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Acclaim for Doc Holliday "Splendid . . . not only the most readable yet definitive study of Holliday yet published, it is one of the best biographies of nineteenth-century Western 'good-bad men' to appear in the last twenty years. It was so vivid and gripping that I read it twice." --Howard R. Lamar, Sterling Professor Emeritus of History, Yale University, and author of The New Encyclopedia of the American West "The history of the American West is full of figures who have lived on as romanticized legends. They deserve serious study simply because they have continued to grip the public imagination. Such was Doc Holliday, and Gary Roberts has produced a model for looking at both the life and the legend of these frontier immortals." --Robert M. Utley, author of The Lance and the Shield: The Life and Times of Sitting Bull "Doc Holliday emerges from the shadows for the first time in this important work of Western biography. Gary L. Roberts has put flesh and soul to the man who has long been one of the most mysterious figures of frontier history. This is both an important work and a wonderful read." --Casey Tefertiller, author of Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend "Gary Roberts is one of a foremost class of writers who has created a real literature and authentic history of the so-called Western. His exhaustively researched and beautifully written Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend reveals a pathetically ill and tortured figure, but one of such intense loyalty to Wyatt Earp that it brought him limping to the O.K. Corral and into the glare of history." --Jack Burrows, author of John Ringo: The Gunfighter Who Never Was "Gary L. Roberts manifested an interest in Doc Holliday at a very early age, and he has devoted these past thirty-odd years to serious and detailed research in the development and writing of Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend. The world knows Holliday as Doc Holliday. Family members knew him as John. Somewhere in between the two lies the real John Henry Holliday. Roberts reflects this concept in his writing. This book should be of interest to Holliday devotees as well as newly found readers." --Susan McKey Thomas, cousin of Doc Holliday and coauthor of In Search of the Hollidays

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1143

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Half Title page

Title page

Copyright page

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Prologue: The Measure of A Man

Chapter 1: Child of the Southern Frontier

Chapter 2: The World Turned Upside Down

Chapter 3: Gone to Texas

Chapter 4: Cow Towns and Pueblos

Chapter 5: The Price of A Reputation

Chapter 6: Friends and Enemies

Chapter 7: The Fremont Street Fiasco

Chapter 8: Vengeance

Chapter 9: The Out Trail

Chapter 10: A Holliday in Denver

Chapter 11: A Living-and Dying-Legend

Chapter 12: The Anatomy of a Western Legend

Epilogue: The Measure of A Legend

Notes

Index

DOC HOLLIDAY

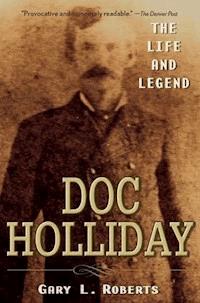

Frontispiece: John Henry “Doc” Holliday, Prescott, Arizona, circa 1879; photograph by D. F. Mitchell.

Copyright © 2006 by Gary L. Roberts. All rights reserved

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New JerseyPublished simultaneously in Canada

Photos courtesy of: frontispiece, pp. 16, 52, 66, 126 (middle), 286, 376, Craig Fouts; pp. 13, 23, 51, 63, 401, Robert G. McCubbin; pp. 18, 59, Constance Knowles McKellar; p. 29, Susan McKey Thomas; p. 37, Regina Rapier; p. 42, Mrs. Fred Arnold Martin Sr. and Charles C. Martin; p. 43, Albert S. Pendleton Jr.; p. 47, Sarah Cranford Bradford; p. 49, University of Pennsylvania School of Dentistry; p. 54, History of Dentistry in Georgia, Georgia Dental Association, 1962; p. 57, Angeline Delegal; p. 71, Buffalo Bill Museum, Cody, Wyoming; pp. 91, 162, Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas; p. 93, Bob Boze Bell; p. 93 (inset), William B. Secrest; pp. 96, 126 (left, right) Arizona Historical Society, Tucson, Arizona; p. 98, Holliday Day House Museum, Fayetteville, Georgia; p. 129, Carl Chafin Collection; p. 151, New York Historical Society; pp. 190, 208, paul johnson; p. 217, Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City, Utah; p. 236, Jack Burrows; p. 253, Peter Brand; pp. 288, 342 (inset), from a woodcut in the National Police Gazette; pp. 342, 371, Western History Collection, Denver Public Library, Denver, Colorado; p. 346, Regina Andrus; p. 361, Kathryn Gardner; p. 393, Dr. A. W. Bork

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and the author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information about our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Roberts, Gary L., date. Doc Holliday : the life and legend / Gary L. Roberts. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13 978-0-471-26291-6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10 0-471-26291-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Holliday, John Henry, 1851–1887. 2. Outlaws—West (U.S.)—Biography. 3. Gamblers—West (U.S.)—Biography. 4. Frontier and pioneer life—West (U.S.)5. Dentists—West (U.S.)—Biography. 6. West (U.S.)—Biography. I. Title. F594.H74R63 2006 364.152′3′092-dc22

2005022233

ForSusan McKey Thomas, John Henry Holliday’s cousin, a true Southern lady in the finest sense of the term and the inspira tion for this book.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A book such as this is built on the generosity of others. Teachers, scholars, researchers, artists, and encouragers (many of whom never realized the role they played) influenced both this work’s conception and explication while instilling a profound sense of humility in me. Countless individuals shaped not only my knowledge of and enthusiasm for this story but also the worldview and sense of history that gave it form and meaning. Regretfully, I cannot acknowledge or even remember all of them, but I am profoundly grateful to each.

My greatest debt is to Susan McKey Thomas, the granddaughter of John Henry Holliday’s uncle, William Harrison McKey. Her encouragement and willingness to share the results of her own prodigious research made this book possible. She has been my mentor, my collaborator, and my friend. Long before I met Susie, though, the seed that spawned this book had already been planted in the living room of the late Alva McKey of Valdosta, Georgia, a first cousin of John Henry Holliday’s. “Miss Alva” made Doc Holliday human for me that afternoon long ago; Susie revived my interest and challenged me to tell his story.

Other members of John Henry’s family helped as well, some directly, some through collaboration with others: Edward R. Holliday, J. William F. Holliday, Robert Lee Holliday, Angeline De La Gal, Cathy E’Dalgo, J. C. E’Dalgo, Morgan De Lancey McGee, J. D. McKey, John McKey, Martha Wiseman McKey, Constance Knowles McKellar, Mac McKellar, Carolyn Holliday Manley, Catharine Holliday Neuhoff, Regina Rapier, Karen Holliday Tanner, I. H. Tillman, and Mrs. Clyde McKey White.

Casey Tefertiller, whose landmark Wyatt Earp: The Life behind the Legend set a new standard for students of frontier violence and its accompanying myths, encouraged me to make an old dream a reality, and provided advice and materials from his own research to help make it happen. Jeffrey J. Morey, a close student of Wyatt Earp and the Tombstone troubles, shared his own research and insights in ways that proved essential to the evolution of this book. Victoria Wilcox was generous to a fault with the fruits of her own research (especially relating to the Holliday family) as well as her unique and challenging perspectives on critical issues that helped me to see old questions in new ways. Robert F. Palmquist, a Tucson attorney and close student of Tombstone’s colorful history, provided sage advice both on the substance of this story and on the peculiarities of the nineteenth-century legal system. Dr. David O. Moline, a dental surgeon and a historian of dental practice, shared critical information based on his own interest in Doc Holliday. The late Robert N. Mullin tutored me in this field for years with rare balance and perception. Without this half dozen, this book would never have been written.

Other researchers took the time to share unselfishly from their own important research in ways that provided new information that modified or informed my understanding. Regina Andrus, John Boessenecker, Arthur W. Bork, Peter Brand, Jack Burrows, Woody Campbell, Bob Cash, Paul Cool, Bruce Dettman, Bill Dunn, Mark Dworkin, Marcus A. Gottschalk, Teresa Green, Chuck Hornung, Roger Jay, Paul L. Johnson, Scott Johnson, Shirley Ayn Linder, William B. Shillingberg, Emma Walling, and Roy Young made critical contributions of this kind.

I have also benefited from the work of Doc Holliday’s previous biographers—John Myers Myers, Patricia Jahns, Albert Pendleton Jr., Sylvia D. Lynch, Ben T. Traywick, Bob Boze Bell, and Karen Holliday Tanner—whose works blazed the trail for my quest for understanding and raised new questions that I might otherwise have missed.

Several private collectors—Carl Chafin, Craig Fouts, Robert G. McCubbin, Kevin J. Mulkins, and C. Lee Simmons—made it possible for me to examine documents that I could not have seen otherwise.

Other individuals, living and dead, who have contributed to this work include Rita Ackerman, Robin Andrews, Scott Anderson, Lynn R. Bailey, Allen Barra, Dr. Ernest Beerstecher, Verner Lee Bell, Mary Billings-McVicar, Peter Blodgett, Mark Boardman, Patrick A. Bowmaster, Jim Bradshaw, Donaly Brice, Richard Maxwell Brown, Tom Bryant, Neal Carmony, Robert J. Chandler, Peter Christoph, Ann Collier, Wayne Collier, Sharon Cunningham, Donald O. Davis, Joe Davis, Robert K. De Arment, Jack DeMattos, Jim Dunham, Joan Farmer, Timothy W. Fattig, Steve Gatto, Tom Gaumer, Treese Hellstrom, Cindy Hines, Dr. L. C. Holtzendorff, Billy Johnson, Troy Kelly, Larry Knuth, E. Dixon Larson, Jennifer Lewis, Joe Lineburger, Randy Lish, Larry Martin, Gary McClelland, Nyle H. Miller, Carolyn Mitchell, Jan Morrison, Roger Myers, Bruce Olds, Clay Parker, Chuck Parsons, Chris Penn, Roger Peterson, Nancy Pope, Pamela Potter, Cyn Poweleit, S. J. Reidhead, Max Roberts, John Rose, Rod Rothrock, Clark Secrest, Larry G. Shaver, Keith Sladic, Chuck Smith, Jean Smith, Joseph W. Snell, Russell Street, John D. Tanner, Ben Tingenot, Kenneth Vail, Lawrence Vivian, Mark Warren, Jeff Wheat, Erik Wright, and Ronald Yeomans.

In my youth I was tutored patiently in the history of Western violence by a remarkable group of historians, book collectors, writers, researchers, and a few direct links to the Western past who shaped my approach to the field. They are gone now, but they were giants to me, and acknowledging them is both appropriate and necessary because of my great debt to them. In addition to Bob Mullin, Ramon F. Adams, Henry Allen (aka Will Henry and Clay Fisher), Ed Bartholomew, William R. Cox, J. Frank Dobie, Jefferson C. Dykes, John D. Gilchriese, Waldo E. Koop, Ethel Macia, Nyle H. Miller, Philip J. Rasch, C. L. Sonnichsen, Zoe A. Tilghman, and Opie Vermillion fed the vision that made this book possible.

The tyranny of space has forced me to confine my acknowledgments of numerous institutions, both public and private, to the extensive notes appended to this volume. I hope that the staffs of these institutions, past and present—literally dozens of people—who so generously helped me across the years will understand. I do not take lightly my debt to them or the places where they work, or have worked.

I am especially grateful to my editor, Hana Lane, and my production editor, Lisa Burstiner, whose patience, direction, and toughness made this dream become a reality.

Finally, I would like to thank my family and friends, especially my stepdaughter, LeahAnn Driscoll, who with one bright smile reminds me that there is a future as well as a past.

I can only hope that the results are worthy of the effort of all of these people—and more—on my behalf.

PROLOGUE

THE MEASURE OF A MAN

There’s no such thing as a normal life, Wyatt. There’s just life. Now get on with it.

—Doc Holliday to Wyatt Earp, Tombstone(1993)

At ten o’clock on the morning of November 8, 1887, at Glenwood Springs, Colorado, a slight, frail man of thirty-six succumbed to the effects of chronic pulmonary tuberculosis. In his last days, John Henry Holliday, his hair silvered and his gaunt form bent and worn from the ravages of his disease, hardly seemed the stuff of legend, although in the words of the local paper, “the fortitude and patience he displayed in his last two months of life, made many friends.”1 But when the Denver Republican noted his passing, the measure of the man came clearer: “Doc Holliday is dead. Few men have been better known to a certain class of sporting people, and few men of his character had more friends or stronger companions. He represented a class of men who are disappearing in the new West. He had the reputation of being a bunco man, desperado, and bad-man generally, yet he was a very mild-mannered man, was genial and companionable, and had many excellent qualities.”2

This somewhat gentle assessment of the career of Doc Holliday underscored a problem that has plagued his biographers across the years since his death. The man was already obscured by his reputation before he was laid to rest in Glenwood Springs. He would be variously described as a Byronic aristocrat embittered by illness, the black sheep of a fine Southern family, a cynical and deadly killer, and a quarrelsome and profligate drunkard, but despite periodic rumors of personal correspondence and other papers that might throw light onto his values and attitudes, Doc Holliday remains more myth than man.

Opinions always varied. Wyatt Earp (through his ghostwriter in 1896) described him as a “mad, merry scamp with heart of gold and nerves of steel; who…stood at my elbow in many a battle to the death.” Earp’s ghostwriter produced a vivid and compelling portrait of Doc—although he had him hail from the wrong state: “He was a dentist, but he preferred to be a gambler. He was a Virginian [actually a Georgian], but he preferred to be a frontiersman and a vagabond. He was a philosopher, but he preferred to be a wag. He was long, lean, an ash-blond and the quickest man with a six-shooter I ever knew.”3

Bat Masterson was less kind, saying that Doc “had a mean disposition and an ungovernable temper, and under the influence of liquor was a dangerous man.” Describing him as “a weakling who could not have whipped a healthy fifteen-year-old boy in a go-as-you-please fight,” Masterson saw him as “hot headed and impetuous and very much given to both drinking and quarreling, and among men who did not fear him, [he] was very much disliked.”4

Virgil Earp called him “gentlemanly,” a “good dentist,” and a “friendly man” and mused that Doc had been blamed for many things that could not be “traced up to his account.”5 The editor of the Las Vegas (New Mexico) Daily Optic—who was safely distant from Doc at the time—described him as a “shiftless bagged-legged character—a killer and a professional cut-throat and not a whit too refined to rob stages or even steal sheep.”6 A fellow Georgian who knew him as a young man and later dabbled in silver mining in Colorado said of him following his death, “He was a warm friend, and would fight as quick for one as he would for himself. He did not have a quarrelsome disposition, but managed to get into more difficulties than almost any man I ever saw.”7

An unidentified newspaperman remarked about Doc in 1882, “Here is a man who, once a friend, is always a friend; once an enemy is always an enemy.”8 Ridgely Tilden, a correspondent for the San Francisco Examiner in 1882, wrote of him:

Now comes Doc Holliday, as quarrelsome a man as God ever allowed to live on earth. A Georgian, well bred and educated, he happened in Kansas some years ago. Saving Wyatt Earp’s life in Dodge City, Kansas, he earned his gratitude, and notwithstanding his many bad breaks since, has always found a friend in Wyatt. Doc Holliday is responsible for all the killing, etc, in connection with what is known as the Earp-Clanton imbroglio in Arizona. He kicked up the fight, and Wyatt Earp and his brothers “stood in” with him on the score of gratitude.9

E. D. Cowen, a Denver newspaperman who met Holliday in 1882, provided yet another view:

A person unfamiliar with Holliday’s deeds…would pass him off as a specimen of human insignificance. Holliday was of medium stature and blonde complexion. He was small boned and of that generally slumped appearance common to sufferers from inherited pulmonary disease. The clenched setting of his firmly pointed lower jaw and the steadiness of his blue eyes were the only striking features of his pallid countenance. He was scrupulously neat and precise in his attire, though neither a lady’s man nor a dandy.…[H]e was too deeply sincere to be voluble of speech and too earnest in his friendships to make a display of them.10

But Charles D. Reppy, John P. Clum’s partner at the Tombstone Epitaph, said flatly, “Holliday was the most thoroughly equipped liar and smoothest scoundrel in the United States.”11

In such fragments, tantalizing glimpses of truth doubtlessly appear, all the more intriguing because of the contradictory images they pose. Yet the measure of the man remains incomplete. The Doc Holliday of history is an individual seen almost entirely through the eyes of others. He remains, essentially, a man without a voice, a circumstance that makes him at once a compelling subject and a frustrating figure. He was a Southerner, a dentist, a gambler, and a consumptive who seemed to have no fear of death. He was Wyatt Earp’s friend and stood with him at the most famous gunfight in the history of the American West. But those are all impersonal qualities and descriptive terms devoid of any true insight into character, personality, or motivation. They explain what he did, not who he was. They are so vague that they permit today, as in his own time, the diversity of opinion expressed by those quoted here.

Not a single sample of his writing that would provide insight into how he felt or what he believed appears to have survived.12 In his lifetime he gave precious few interviews, and they are disappointing—except to the extent to which they reveal Doc’s humor and studied disdain for the whole process of interview. He never stands clear as a historical figure in sharp relief. Perhaps that is his charm, the reason that in history books, novels, and motion pictures, though he would be unknown without his association with Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday forever steals the show from the plodding, humorless, but always imposing Mr. Earp, who was clearly the central figure in the events that transpired in Tombstone, Arizona, during the troubled months of 1881 and 1882.

And so, curiously, for one so well known, Doc Holliday remains a mystery, a legend in the shadows. That is his charm and his frustration for would-be biographers. Biography is, after all, an arrogant, intrusive enterprise. It probes lives in all the places that people prefer to have left alone. Those who do it justify it usually because they find something compelling about a life or because they have a passion to bring down idols. In either case, biographers have purposes more complicated than simply “telling it like it really happened.”

Biographers reveal much about themselves as well as about their subjects. None of them writes in a vacuum, nor should they, because biography—like all history—amounts to processing lives and events through third-party perceptions to gain the measure of a person and a time. Biographers inevitably see their subjects differently than the subjects saw themselves. No matter how honest, how forthright a subject is, distortions will come from what he or she says, or what he or she leaves out.

The truth of a life is more than a sum of the facts. A life is not merely about what a person does, but also about what a person thinks, feels, and values and how he or she affects the people and events around him or her, because ultimately what biographers and readers want to know is what a person’s life means. And meaning involves more than how a person sees himself or herself or even what a person does. Meaning also involves how others see a person, and the perception of others is not always based on the truth of a life or even complete knowledge of it. So, then, approaching the life of a man like John Henry Holliday is complicated by the fact that the man behind the legend is obscured by conclusions and opinions that created the legend in the first place.

Without a body of letters or even reminiscences written by him that would serve as a corrective to the half-known life presented in the opinion-gripped contemporary press and the memories of men and women who saw him through the lenses of their own agendas and emotion-packed prejudices, John Henry Holliday tantalizes the biographer with unanswered questions. He did not have a frontierwide reputation until after his experiences at Tombstone in 1881 and 1882. Before then, his life did not always leave a clear trail. As a result, much of his life—even many of its most critical moments—are left to informed speculation and possibilities. This work, then, is not the final word on the life of Doc Holliday; it is, rather, an informed quest to understand the man and his legend that will point the way to further discoveries, raise new questions, and provide some answers in the search for meaning in the life of this brooding metaphor of the moral contradictions of life on the late nineteenth-century frontier.

Chapter 1

CHILD OF THE SOUTHERN FRONTIER

[T]o ignore the frontier and time in setting up a conception of the social state of the Old South is to abandon reality. For the history of the South throughout a very great part of the period from the opening of the nineteenth century to the Civil War…is mainly the history of the roll of frontier upon frontier—and on to the frontier beyond.

—W. J. Cash, The Mind of the South

The Old South is more an idea than a place or a time. In the popular mind it conjures up images of white-columned plantation houses surrounded by moss-bound oaks, magnolias, dogwoods, and azaleas in bloom, vast fields of cotton, gangs of slaves, and the full range of characters straight out of Gone with the Wind. Perhaps that is why it is almost irresistible to think of Doc Holliday as the scion of a plantation family or why one biographer could not resist characterizing him as “aristocracy’s outlaw.”1 His story is infused with what might be called the Southern mystique as thoroughly and profoundly as it is with the legend of the last frontier. And so, the man behind the myth is both magnified and obscured by a double distortion.

Ironically, from the beginning John Henry Holliday was as much a child of the frontier as he was of the Old South. Indeed, he lived most of his youth on what was even then known as the Southern frontier. Georgia was the youngest of the original thirteen colonies, and although the young country of which it was part had pushed westward all the way to the Pacific Ocean by the time he was born, John Henry’s childhood was spent in the red-clay country of Georgia only a few years distant from the time that the region was the domain of the Creek Nation. When the course of the Civil War persuaded his father that he should move his family beyond the reach of General William Tecumseh Sherman’s armies, the young John Henry was transplanted into the piney woods and wiregrass of southwest Georgia, a thinly populated region of subsistence farmers and free grazers until the railroad gave it life and opened up economic opportunities in much the same way that the railroad generated the boomtowns of the last West.

Despite its ambitious claims, Georgia entered the nineteenth century still largely the homeland of the Creeks and the Cherokees. The tidewater region was already shifting its economic base from rice and indigo to the Sea Island cotton that would revitalize slavery and bring prosperity to the state, but the tidewater could not hold the burgeoning population. Restless settlers were pushing west along rivers into the interior, mindless of the claims of the natives and certain of their own “right” to be there.2

There was a Celtic edge on the invasion. Willful, sensate sorts, the Scots, the Irish, and the Scots-Irish generated a “Cracker” culture marked by fighting, drinking, gambling, fishing, hunting, idleness, and independence. They faced Georgia’s frontier with the same leisurely attitudes of their Scottish and Irish forebears, and the open-range tradition they brought with them moved them into the interior before the agricultural potential was fully realized and created a values system at odds with the stern Yankee Puritanism and nascent capitalism that held sway to the north.3

At the heart of this Southern society was a fierce determination of its people to resist restrictions on their independence and movement. Their belligerence first manifested itself in their contest with the Indians. The Creeks did not call white Georgians E-cun-nau-nux-ulgee (People-greedily-grasping-after-land) for nothing.4 Settlers assumed a right to go where they chose, and Georgia was perpetually a thorn in the side of not only the natives but federal Indian policy as well. In the nineteenth century, Georgia developed a liberal land lottery system for the distribution of land as an incentive to dispossession of the Indians, and in the first four decades of the 1800s, sixty-nine counties were created, while the population soared from 162,000 to 691,000.5

By November 1827, the last claims of the Creeks were ceded at the second Treaty of Indian Springs not far from where John Henry would be born, and Georgia turned its sights on the Cherokees as the last obstacle to Georgia’s sovereignty over lands within its boundaries. The Cherokees attempted to avoid the fate of other tribes through acculturation. They sought to avoid being labeled as “savages” by adopting “civilized” ways. The Cherokees had a written constitution, their own alphabet, a newspaper, schools, an elected legislature, and a permanent capitol at New Echota. Georgia ignored constitutional restrictions on its powers to deal with the Indian tribes and declared on December 28, 1828, that the Cherokee Nation was part of Georgia and subject to its laws. Later, even after the U.S. Supreme Court took a hand in restraining its excesses, Georgia ignored court edicts as well as treaty rights and began the process of overrunning Cherokee lands and suppressing Cherokee laws. Following the discovery of gold in North Georgia in 1829 and the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830, the state ordered Cherokee lands to be surveyed in 1831, divided the region into ten new counties the following year, and gave away the land to whites in the Cherokee Lottery of 1833.6

Georgia then proceeded to confiscate Cherokee lands, occupy New Echota, and destroy Sequoya’s newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix, because of its opposition to removal. The federal government, rather than Georgia, eventually capitulated. Notwithstanding the Supreme Court’s clear decisions in favor of the Cherokees, President Andrew Jackson refused to enforce the high court’s rulings.7 After the Georgians invaded Cherokee lands, tribal leaders appealed to Jackson directly, and he—wrongly—told them he could do nothing. When he failed to side with the Indians, the tribe divided into two factions: one accepting removal as the lesser of evils, the other determined to fight on.

Although the vast majority of Cherokees, led by John Ross, flatly opposed removal, federal authorities met with the treaty party led by Major Ridge at New Echota on December 19, 1835, and negotiated the sale of the Cherokee domain of eight million acres for $5 million, despite death threats against the treaty signers by the majority. When Ross’s faction refused to migrate, the federal government sent General Winfield Scott to forcibly remove the remaining Cherokees. Eventually, thirteen thousand men, women, and children were rounded up and herded west to the Indian Territory on the Trail of Tears.8

The Holliday family was a beneficiary of that tragic story. John Henry’s father, Henry Burroughs Holliday, was a self-made man—Andrew Jackson’s “common man”—the kind of man nineteenth-century Americans celebrated.9 His people were plain folk in the Old South. Henry’s paternal great-grandfather, William Holliday, was one of three Scotch-Irish brothers who immigrated to America from Ireland sometime after 1750. He settled in the Laurens District of South Carolina, while his brothers, “objecting to settle in slave states,” moved north, as Henry later recalled. William and his sons fought in the American Revolution with the “hero of Hornet’s Nest,” Elijah Clarke, and took their first lands in Wilkes County, Georgia, from bounties for that service.10

Later, William Jr., Henry’s grandfather, returned to Laurens County, South Carolina. There, his son, Robert Alexander Holliday, met and later married Rebecca Burroughs, whose father had also fought with Elijah Clarke in the American Revolution. Henry Holliday was born to them on March 11, 1819, the first of eleven children.11 After his father’s death, Robert relocated to Anderson County, South Carolina, and in 1831 he followed opportunity into Georgia with his family and eight slaves. He opened a tavern on the road between Newnan and Decatur near Fayetteville and eventually bought an eight-hundred-acre farm in Fayette County, which was part of the old Creek Nation. Over the years, he enlarged his holdings and became a respected and well-known citizen.12

Like most white Georgians, emboldened by President Jackson’s support of the state’s position, the Hollidays saw the Cherokee removal as inevitable and right. The bulk of General Scott’s force consisted of volunteers from Georgia, Tennessee, and North Carolina. On May 12, 1838, young Henry, still shy of twenty, enlisted in Fayetteville as a second lieutenant in Captain John D. Stell’s company of the First Georgia Volunteers to help effect the final removal of the Cherokees from Georgia.13 By May 26, 1838, Scott began operations. He urged the troops to act with humanity and mercy, but a contemporary observer reported that “[i]n most cases the humane injunctions of the commanding general were disregarded.”14

It was disagreeable duty at best, taking men from their fields, women from the hearth, and children from play to push them at gunpoint to relocation centers, but many of the undisciplined and ill-trained militiamen seemed to enjoy the duty too much, taunting their captives and not allowing them time even to gather clothes and other items from their homes for the journey. A motley rabble followed behind the troops, burning homes and crops or moving into cabins to eat the food still cooking over the fires and to plunder the farms before the former owners were out of sight. Z. A. Zile, a Georgia militia officer who later served as a colonel in the Confederate army, would recall, “I fought through the civil war and have seen men shot to pieces and slaughtered by thousands, but the Cherokee removal was the cruelest work I ever knew.”15

The Cherokees were held in makeshift stockades where sanitary conditions were awful and sickness and despair set in quickly. By June 18, General Charles Floyd of the Georgia militia reported to Governor George M. Troup that the only Cherokees left in Georgia were prisoners. General Scott now dismissed all troops save his regular army units, and the youthful Holliday, not yet twenty years old, was discharged with his company at New Echota on June 20. Having done his part to start the Cherokees west on their Trail of Tears, Henry received 160 acres of land in Pike County for his scant service and turned his thoughts to his own future.16

The rich red clay of the region was slowly freed from the forest by the sweat of white men and black men and turned under to become the new heart of Georgia’s cotton belt. The luxuriant Sea Island cotton would not grow well there, but the cotton gin made short-staple cotton practical and profitable. These developments allowed cotton to flourish in the upcountry, but Georgia’s economy was much more diverse than popular myth allows. Corn, wheat, oats, rice, tobacco, sweet potatoes, molasses, honey, butter, horses, mules, sheep, cattle, and swine completed a remarkably diverse agrarian way of life. White settlers poured into the new country of the piedmont, and early arrivals like the Hollidays made the most of their opportunities in the new country they had confiscated.17 Henry settled at the new town of Griffin.

But if Henry Holliday was the product of the forces that glorified the common man in the “age of Jackson,” his was also a society driven by notions of honor, manhood, family, and community. Henry could claim no genteel tradition. There is much in the myth of the Old South about class. Both the cavalier tradition and the Northern critique of Southern life assume a rigid class system in the South similar to the class structure of Georgian England.18

Despite the pretensions of some, it was always largely a fiction in much of the Old South. This is not to say that there were no social distinctions, but that they have been misunderstood. In the first place, there were simply too many planters who wore white gloves to hide the calloused hands that betrayed their common origins and who shared values with the great bulk of ordinary Southerners. Outside of Virginia and a slender strip of tidewater through the Carolinas and Georgia, inherited wealth and position simply did not exist. The great heart of the Cotton Kingdom was frontier. There, rank, and even wealth, were not controlling factors in the measure of men. As was true on other frontiers, the great virtues and marks of distinction were more personal. Courage, strength, conviviality, ability with weapons, skill at cards, keeping one’s word, a readiness to defend one’s honor, and even the ability to hold one’s liquor were just as important.19

Ironically, black slavery preserved a certain egalitarianism among whites. As W. J. Cash pointed out long ago, one of the oddities of the “peculiar institution” was that slavery served as a leveler that preserved independence and individualism and prevented the development of a rigid class system among whites. Middling and even poor whites were neither directly exploited by the Southern aristocracy nor dependent on it. The result, Cash noted, was “the almost complete disappearance of economic and social focus on the part of the masses. One simply did not have to get on in this world in order to achieve security, independence, or value in one’s estimation and in that of one’s fellows.”20

For people like Henry Holliday, then, there was no real sense of social or economic limitation. His people were plain folk, and he lacked both the learning and piety of gentility. But Holliday nurtured the sense of honor, self-worth, magnanimity, and independence needed to forge a place for himself in the upcountry environment while he speculated in land and sought other economic opportunities. He acquired town lots and farmlands as the base for economic security, but, more important, he gained acceptance among his neighbors as a tough but fair-minded and honorable man.

Reputation was everything in the Old South. The opinion of others was a measure of inner worth. Virtue, honor, valor, and respect simply did not exist apart from the view of a man in the minds of other men. Some of the truculence for which Henry Holliday would be remembered by those who knew him doubtless arose from the aggressiveness and steadfastness that Southerners expected of leaders, but he also exhibited the attention to manners, courtesy, and hospitality that the social order demanded of community leaders. External, public factors established personal worth, and Henry made a place for himself in that milieu.

Henry Burroughs Holliday, father of John Henry Holliday.

Making a place for oneself in the antebellum South was a different process from making a place for oneself in New England or other points north. It was less about capital success, sobriety, piety, class consciousness, and the Puritan work ethic than about sociability, honor, manliness, and loyalty to family and neighbors. It was a difference that puzzled Northerners, who dismissed Southerners as a profligate, lazy, and peculiarly violent species. Still, undeniably, Northerners were drawn to, if not charmed by, a warmhearted grace in their social intercourse that was lacking in the more sober, cautious, reasoned, and dignified Yankee ethic.21

Southerners assumed a harsh life, and fate was a part of it. They ordered life with a code of honor, a code rooted not so much in conscience as in pride. Honor imposed duties on every man. It called for self-restraint. It demanded courtesy toward others, even enemies, that sometimes struck outsiders as hypocrisy. And yet it allowed, even demanded, room to act impulsively to defend one’s reputation and self-esteem. In the nineteenth century, especially among the middling and working classes, evangelical Christianity modified the foundations of the code for some to demand a higher standard of moral virtue with respect to such matters as fighting, drinking, and gambling, but Southern honor retained a distinctive character in which sociability and manliness were paramount and manifested, respectively, in loyalty to community and in personal independence.22

There was a martial air, what might even be called a warrior spirit, that prevailed in the South, and it fed the imagery of violence. Some observers attributed it to the dehumanizing impact of slavery, but recent historians credit the Celtic heritage and its peculiar notions of honor and individuality as the primary culprit.23 Whatever the source, Southern individualism, independence, and codes of honor meant, practically, as Cash put it, that every Southerner regardless of station was prepared to “knock hell out of whoever dared to cross him.”24 Here was the origin of the brawling, dueling, and lynching that existed in the Old South to a greater degree than elsewhere, but here, too, was the harbinger of nobility, romanticism, and patriotism that made the Southerner a formidable fighting man in defense of family, community, and country.

In 1846, with the eruption of the Mexican War, Southerners flocked to the colors. Henry Holliday traveled to Columbus, Georgia, on the Chattahoochee River, with a company of men from Griffin who called themselves Fannin’s Avengers, after the martyred Colonel James Fannin, a former Georgian whose command had been massacred in 1836 at Goliad during the Texas revolution. Holliday was commissioned a second lieutenant in Company I, and his company served in the regiment of Colonel Henry R. Jackson of Savannah.25 They were soon bound for Mexico, where Jackson’s regiment was in the thick of the fight with General Zachary Taylor at Monterrey and served with distinction at Veracruz and Jalapa under General Scott. Discharged at Jalapa on June 1, 1847, Henry Holliday continued to serve as a clerk in the army’s Commissary Department for a time.26

When Holliday returned to Griffin, he revealed a side of himself that might not have shown itself easily through his rough exterior. He brought with him a Mexican boy named Francisco Hidalgo, who had been orphaned by the war, and took him into his household, though at the time Henry was still a bachelor.27 That was about to change, however. Henry had his eye on Alice Jane McKey, the nineteen-year-old daughter of William Land McKey and Jane Cloud McKey, whose Indian Creek cotton plantation attested to the family’s prominence and success. How and when they met is not evident from the record, but that Alice Jane responded to his courtship was a coup for Henry, ten years her senior, and evidence of his progress toward goals that satisfied his prospective in-laws as well as himself. Henry and Alice Jane were married on January 8, 1849, and the couple moved into a house on Tinsley Street north of the railroad tracks in Griffin.28

Alice Jane brought added respectability to Henry. Like the Hollidays, her parents had moved to Georgia from South Carolina. By 1849, they were well-known and respected citizens of Henry County. Her father was well-born himself, while her grandfather, Joseph Cloud, was a member of one of the wealthiest slaveholding and landholding families in the region, owning property for a distance of more than fifty miles from Stone Mountain to Griffin. Henry’s acceptance by the McKeys was itself evidence of his growing reputation and success.29

Henry settled into married life at Griffin as a druggist and began to build a reasonably good life for his aristocratic wife and himself. He was soon a prominent citizen, noted as a hard-nosed businessman and a quick-tempered adversary. Griffin prospered, benefiting from a railroad line that ran from Atlanta to Macon and from the slaves who worked the surrounding cotton fields. It soon became a central point for shipping cotton. Its future seemed bright if not certain.30 Henry grew with the town, speculating in land and eventually acquiring forty-six plots within the town limits and hundreds of acres in the county as well as potential railroad properties in other parts of the state.

By all accounts, Alice Jane was a refined, genteel, and pious woman, as befitted her background, a wife devoted to her husband and committed to charity and church. Reared a Methodist, she joined the Presbyterian church in Griffin to bring the family together in matters of faith, although she never personally embraced the doctrine of predestination. Henry had married well, and she gave him the kind of home that enhanced his social position as well as fostered the family Henry wanted.31

Alice Jane McKey Holliday and infant John Henry Holliday, circa 1852.

They wasted little time. On December 3, 1849, Alice Jane gave birth to their first child, Martha Eleanora, one day before President Zachary Taylor angered Southerners by proposing the admission of California and New Mexico as states without territorial status first.32 Like the compromise that took shape in Congress over the next few months, little Martha was frail and brought only a brief period of joy to her parents. On June 12, 1850, she died and was buried at the small cemetery in Griffin.33 The grieving couple was surrounded by the extended families of Hollidays and McKeys. John Stiles Holliday, Henry’s younger brother, was a prominent Fayetteville citizen, medical doctor, and businessman, with a growing family of his own. Alice Jane’s parents were also nearby. Childhood death was a fact of life in those days; five of Henry’s brothers and sisters had died before the age of ten. So the young couple coped and planned to try again.

The infant Compromise of 1850 was in trouble, too, by August 14, 1851, when a second child, a son, was born to Henry and Alice Jane. The boy was likely delivered by John, who came down from Fayetteville for the occasion. They named him John Henry Holliday, after his uncle and father, and he became the center of their world. The Holliday family was both large and close, so John Henry’s birth was a major event in the life of the whole family. As the eldest son of the eldest son, young John Henry was destined to play a large role in family life. As he was the primary heir, the guardianship of the family’s good name would one day fall into his charge. The Hollidays celebrated and made plans for the future in light of this new birth.34

One family source—and curiously only one—recalled that John Henry was born with a cleft palate.35 Mary Cowperwaithe Fulton Holliday, the wife of John Henry’s cousin Robert Alexander Holliday (and a person who never met John Henry herself), reportedly wrote that the “most distressed” John Stiles Holliday consulted with his colleague and cousin by marriage, the renowned Dr. Crawford W. Long, who assisted him in the delicate surgery closing John Henry’s cleft palate, using ether as an anesthesia.36 If true, this was an extraordinary event that should have made news throughout the country, not only for Long, who was involved in a public controversy about the use of ether at the time, but also for Holliday, who would have won accolades for the successful delicate surgery.

In 1842, Long had removed a small cystic tumor from the neck of a patient using ether, but he published no paper on his discovery. In 1846, Dr. John Collins Warren of Massachusetts General Hospital experimented with ether, and in November of that year, Henry J. Bigelow published an article in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal announcing to the world the successful use of ether as an anesthesia. The reputations of Warren and Bigelow gave the procedure credibility, and they were heralded as the discoverers of ether’s anesthetic powers.37

Once the Bigelow article had been published, Long tried, after the fact, to assert his own claim as the discoverer of ether’s use as an anesthesia. Long blamed his failure to act earlier on a “very laborious country practice,” and, once his discovery became public in Jackson County where he lived at the time, his practice fell off, he suffered some community ostracism, and one local elder told him that “if he should have a mistake and kill someone with ether, there was not a doubt but that he would be lynched.” But by 1851 he was involved in a very public controversy with Warren and Bigelow on the subject. His use of ether at an early date would eventually be verified and recognized, but because he did not publish a report of his discovery, the medical community did not, as the leading medical historian William H. Welch said, “assign to him any influence upon the historical development of our knowledge of surgical anesthesia or any share in its introduction to the world at large.”38 Regardless, in 1851 he was still very much involved in an effort to assert his claim, and success in an operation as complex as cleft palate surgery on an infant would have been a noteworthy accomplishment in any case.

Dr. John Stiles Holliday, brother of Henry B. Holliday, who delivered John Henry Holliday and played a role in his nephew’s life.

Long was living in Atlanta in 1851 and, at least theoretically, would have been available for such a procedure, although no contemporary source has yet been found to confirm it. This seems a little odd, because Long had learned the hard way the importance of reporting medical breakthroughs. Cleft palate surgery on an infant using ether was a formidable challenge, requiring better than average skill and luck as well as specialized tools. The surviving papers of Long, which detail many of his operations—most less significant than the complicated procedures of cleft palate surgery—contain no hint of such an operation, even though he was publicizing his discoveries, documenting examples of their use, and emphasizing their importance during the very time when the operation would have occurred.39

A successful cleft palate surgery on a small child was certainly newsworthy—and under anesthesia, extraordinary and groundbreaking. Several innovations were introduced between 1844, when Sir William Fergusson first outlined operative procedures for cleft palate surgery “founded on anatomical and physiological data,” and 1877, when Francis Mason published his work “On Harelip and Cleft Palate,” but notably the first successful cleft palate surgery under anesthesia was not reported until a physician named Buzzard announced his use of chloroform in 1868.40 If Holliday and Long did perform such an operation on John Henry, it was a major event, and, in light of his previous battles to gain recognition for his work, Long’s failure to publish reports of it was inexplicable.

Cleft palate surgeries were performed as early as possible because of the complications of feeding infants caused by the condition and because of possible speech impediments occasioned by waiting until after a child began to speak before operating. The latter consideration argued for surgery before the second birthday, but surgery within the first several months was discouraged because of the shock to the infant’s system, the belief that small children did not “bear the loss of blood well,” and the simple fact that early efforts often failed to close the cleft satisfactorily.41 Given the complexity of the surgery, the specialized knowledge and tools required, and the complications of using anesthesia on an infant at that point in time, such a procedure would have been virtually impossible outside of a hospital or without receiving public notice.

If such a surgery was performed on John Henry, it would have certainly happened in 1851 or early in 1852 at the latest, because Long moved to Athens, Georgia, in 1852. If John Henry was born with a cleft palate, it was never obvious in the photographs of him, even as a baby (the earliest of which was almost certainly taken before any surgery could have occurred). Of course, a posterior cleft would not have affected the lip or the upper jaw and would not have created a facial deformity. According to Mary Holliday, the cleft “extended to, but not through, his lip.”

No convincing evidence exists to support the claim of a cleft palate. Still, the possibility of such a surgery must be considered because of the potential impact on both his physical and social development. If he did suffer from such an impediment, it doubtlessly affected him in two ways: first, by tying him closer to his mother and delaying the “dropping of the slips”—the point, usually about age four, when boys began to wear pants—and, second, by causing him to be, in the words of Mary Holliday, “somewhat self-conscious” and “withdrawn.” This would help to explain the child’s distance from his father and a perception of Doc as a “mama’s boy.”42 Unfortunately, the weight of evidence does not provide any real support for the claim.

John Henry was baptized on March 21, 1852, at the Griffin Presbyterian Church.43 By then, Spalding County had been created, and Henry Holliday had become the first clerk of the superior court.44 As he prepared to take office in December 1851, a state convention convened at Milledgeville to consider Georgia’s course in light of the Compromise of 1850. On December 10, the attendees agreed to abide by the compromise but warned against further encroachments against slavery.45 The following year saw the compromise jeopardized, and although Franklin Pierce was elected president supporting it, the Free-Soil Party and the controversy surrounding Harriet Beecher Stowe’s best-selling Uncle Tom’s Cabin guaranteed that the issue had not been resolved. Men clung to the hope that it could be amicably settled but feared it would not be. And in it all, Southern solidarity was growing with a widespread perception that the South’s way of life was under siege.

As the linchpin of Southern society, slavery involved much more than morality or even economics. In the South—indeed, in the country at large—the issue was not so much the effect of slavery on blacks but its effect on whites.46 What was at stake was the very balance of white society, the shattering of all the social conundrums of Southern life, and the anticipated reordering of the Southern way of life from top to bottom along the lines of the hated Yankee model. If Southerners rationalized the evils of slavery, they did so by making the contest one of honor, principle, and will. To the forefront rushed all the personal pride, individualism, and community solidarity that transcended class and welded together a fervent belief that the coming conflict was above all self-defense.47

Henry’s stance on the issues can only be assumed based on his rising position in the community. Though he was not a planter, he did own slaves, and the perceived threat to Southern institutions jeopardized his upward mobility. Moreover, he shared popular views about Southern rights and Yankee meddling. Ever the individualist anxious to improve his lot and that of his family, Henry doubtless measured his future in terms of Southern unity. There was honor at stake, a way of life, and the images of Henry that have passed down the corridors of family remembrance are reminiscent of a contemporary portrait of the Mississippian Sargent Prentiss:

Instant in resentment, and bitter in his animosities, yet magnanimous to forgive when reparation had been made…[t]here was no littleness about him. Even toward an avowed enemy he was open and manly, and bore himself with a sort of antique courtesy and knightly hostility, in which self-respect mingled with respect for his foe, except when contempt was mixed with hatred, and then no words can convey any sense of the intensity of his scorn.48

The future that Henry sought for himself and his family was linked to the social order that had spawned him. Honor was separate neither from responsibility nor from safety for family and society. And the very solidarity of viewpoint that he shared with his neighbors and kinsmen gave to him and to them a sense of confidence and power, so that there was no loss of optimism about the future, only a fierce, resolute determination to ensure that it would not be disrupted. So then, Henry set his eyes on the tasks at hand, the practical matters of business and family, and he was unwilling to sacrifice the present with fears about the future.

Alice Jane’s mother died on January 26, 1853, beginning an eventful year that would involve other changes.49 In October 1853, Henry sold his house on Tinsley Street and bought a new home and land northwest of Griffin near the railroad tracks.50 Little John Henry was not yet two years old when Francisco, his name anglicized to Francisco E’Dalgo, moved out to start his own family. He married Martha Freeman in Butts County on June 12, 1854, and settled down there.51 And even though Henry and Alice Jane had no more children after the birth of John Henry, the house was soon full again. On November 9, 1856, William Land McKey, Alice Jane’s father, also died, and Henry became the guardian of his wife’s minor siblings, Thomas Sylvester, Melissa Ella, Eunice Helena, and Margaret Ann, as well as guardian of their inheritance and his wife’s.52

Tom McKey, who was fourteen when his father died, became the older “brother” whom John Henry idolized as he grew. John Henry had already dropped the slips before Tom moved in. He turned six with “bleeding Kansas” in the news. For him, though, the education of a gentleman had begun already, both in the manners of the wellborn taught by his mother and in the stern demands of Southern manhood imposed by his father. Southern boys of all classes were given a surprising amount of freedom as children so as not to limit their aggressiveness or to feminize them with a strict discipline that would break their spirits.53

At an early age they learned independence, took to the fields and woods, and began their tutelage in hunting, the handling of firearms, and horseback riding. They were also taught deference to their elders and learned the “Sir” and “Ma’am” required of them in speaking to adults whether highborn or low. Courtesy, spirit, and firmness were all part of the curriculum of individualism that Southern sons learned, but care was taken not to undermine their self-confidence or pride.

So John Henry grew. Nurtured by his extended family, he learned a way not so different from the aristocratic ideal that his mother wanted to teach him. “The result,” as Cash wrote of Southerners in general, “was a kindly courtesy, a level-eyed pride, an easy quietness, a barely perceptible flourish of bearing, which for all its obvious angularity and fundamental plainness, was one of the finest things the Old South produced.”54 From his father came a sense of personal honor and discipline; from his mother came a proper sense of manners and the principles of faith. Cousins, uncles, aunts, and neighbors filled out the life of a child growing.

In 1857, John Henry’s uncle, Robert Kennedy Holliday, moved to Jonesboro with his family so that most of the Hollidays and McKeys were now within the triangle of Griffin, Fayetteville, and Jonesboro, close enough for support and frequent visits. Robert’s wife, Mary Anne Fitzgerald, was a devout Roman Catholic. His daughters, Martha Anne (called “Mattie” by the family), Lucy Rebecca, Mary Theresa, and Roberta Rosalie, added yet another dimension to John Henry’s experience. Mary Anne Holliday’s uncle, Philip Fitzgerald, and his wife, Eleanor, were also part of the family circle.55 Then in 1859 Henry agreed to assume the guardianship of a young orphan named Elisha Prichard, who moved in with the family.56

The family prospered. Land holdings mounted. Martha Holliday, the sister of Henry and John Stiles, married James Franklin Johnson, a planter, lawyer, and state senator, which extended the family’s influence.57 Close at hand, the future looked bright. Not even the Panic of 1857 dampened optimism. Indeed, Southerners saw its mild impact on them as evidence of the superiority of their system.58 Griffin grew—its population approaching three thousand by the end of the decade, making it the largest city between Atlanta and Macon—and offered amenities and opportunities found in few Georgia towns, including three colleges and a public library.59 Despite growth and prosperity for Griffin, however, the boiling clouds and rolling thunder of politics were increasingly difficult to ignore.

The election of 1856 had come and gone. The Democrat James Buchanan gave Georgians little reason for optimism. They found hope in the Dred Scott decision, but were soon disillusioned by open defiance of its precepts. They were more disturbed by the growing strength of the new Republican Party in the congressional elections in 1858. They saw the Fugitive Slave Law declared unconstitutional in Ableman v. Booth and recoiled at news of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in October 1859.

Robert Kennedy Holliday, brother of Henry Holliday and father of Martha Anne “Mattie” Holliday, with whom John Henry had a close relationship.

Senator Robert Toombs, known as Georgia’s “Son of Thunder” and considered a moderate in Congress by most observers, became convinced that further compromise was impossible, the Georgia legislature passed resolutions condemning John Brown’s “aggressions,” and Joseph E. Brown, Georgia’s fiery governor, set up factories for the production of weapons and gunpowder and ordered the Georgia militia to make preparations for the “inevitable conflict” to come. There were still Georgia voices, like that of Alexander H. Stephens, who urged caution and restraint, but the martial spirit was gaining momentum in Georgia as it was in other Southern states.60

The crazy-quilt election of 1860 found Georgia in turmoil. The Democratic Party had divided into Northern and Southern factions, meeting in Baltimore, Maryland, and Richmond, Virginia, respectively, and a splinter group calling itself the Constitutional Union Party added more confusion. The nomination of Abraham Lincoln by the Republicans did not factor into Georgia’s election, but still the vote was so close among the other three candidates that the legislature had to decide where Georgia’s electoral votes would go. Lincoln was elected president without Georgia’s votes so that the exercise was perfunctory at best, so much so that Governor Brown urged the legislature not to bother. Then on December 20, 1860, South Carolina formally repealed its ratification of the U.S. Constitution and seceded from the Union. In Griffin, Fayetteville, and Jonesboro, the Hollidays, McKeys, Johnsons, and Fitzgeralds were caught up in the anger against the North and the debate over what Georgia should do.61

In the end, despite the eloquence of men like Stephens, Benjamin H. Hill, and Hershel V. Johnson, who urged moderation and caution, a referendum was held, and the people voted 50,000 to 37,000 to follow South Carolina’s example and defend Georgia’s honor in the only manner left to it. On January 19, 1861, Georgia declared itself an independent state.62 It was not immediately apparent what course Georgia would take, but in February Georgians played prominent roles in the convention that convened in Montgomery, Alabama, to draft a constitution for the Confederate States of America. On March 16, Georgia formally adopted the new constitution and became a state in the new Confederacy.63

John Henry Holliday’s world was about to change forever.

Chapter 2

THE WORLD TURNED UPSIDE DOWN

Defend yourselves, the enemy is at your door!

—Senator Robert Toombs, January 20, 1860