Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The employment of female labour on farms during two world wars was essential to replace thousands of men who relinquished agricultural jobs to join the armed forces. 'Land girls', the majority of them from urban districts, maintained supplies of grain, horticultural products and livestock, succeeding in overcoming substantial reductions in food imports caused by disruptive enemy action to the pattern of shipping trade. Hampshire played a major part in the national selection, training and placing of land girls on farms. They undertook hard, physical work in all weathers for many hours a day, often a long way from home. It is generally agreed that Women's Land Army members received inadequate recognition for their valuable contributions. Seventy-five years after the final disbandment of the Women's Land Army, this book intends to correct that deficiency and shed light on its invaluable work.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 195

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© John K. Lander, 2024

The right of John K. Lander to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 752 0

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Typesetting and origination by The History Press.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

Contents

Dedication

List of Illustrations

Abbreviations

Foreword

About the Author

Preface and Acknowledgements

Part 1: First World War, 1914–1918

1: Introduction

2: Initial National Response to Labour Shortages on Farms

3: Hampshire’s Responses to Labour Shortages on Farms up to 1916

4: The Women’s Land Army from March 1917, Nationally and in Hampshire

5: Post-war Experience

6: Postscript

Part 2: Second World War, 1939–1945

7: Introduction

8: Early Women’s Land Army Training at the County Farm Institute, Sparsholt

9: Women’s Land Army Members’ Experience in Hampshire 1939–1942

10: Expansion of Women’s Land Army in Hampshire, 1943–1945

11: Continuing Role for Women’s Land Army After 1945

12: Conclusion

Appendices

A: Profile of a Land Girl – Gwendoline (Gwen) Raggett (née Place) MBE

B: Hymn of the Hampshire Countryside

C: Two Poems Written by Isabella D.S. Waddell in 1941, Aged 22

D: Women’s Land Army Uniform

Notes

Bibliography

Dedication

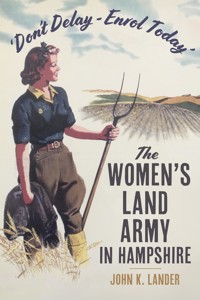

‘Don’t Delay – Enrol Today’1 is dedicated to two unassuming but remarkable women who were members of the Women’s Land Army in Hampshire. They epitomise the invaluable service given to the nation by tens of thousands of women and girls in land-based jobs in two world wars.

Mary Elizabeth (Liz) Bridges (née Cheal)

1929–2023

Gwendoline (Gwen) Yvonne Raggett (née Place)

1926–

List of Illustrations

p.28

‘English girls learning the trade of farming to take the place of farmers who have gone off to war, Sparsholt, Hampshire, England, 26 April 1915. Here they are seen following the harrow.’ (Getty Images, serial no. 167182537; Underwood Archives)

p.29

Westley Farmhouse, Sparsholt, built circa 1870. (Sparsholt College)

p.36

Romsey Remount Depot, Isolation Hospital (National archive catalogue no. WO161/117)

Memorial Statue in Romsey War Memorial Park, commemorating the work of the Romsey Remount Depot.

p.39

William Palmer, 2nd Earl of Selborne, President, Board of Agriculture, 1915–1916. (Bassano Ltd, via Wikipedia)

p.42

‘WOMEN wanted at Once FOR THE LAND’.

‘The Women’s Land Army needs YOU to-day’.

p. 45

Women’s Land Army Rally, Andover, 1916. (WLA website)

p. 50

Certificate signed by Rowland Prothero and Arthur Lee.

Good Service Ribbon Badge (Land Army Agricultural Section).

p.54

Certificate of Discharge on Demobilisation.

p.56

The Landswoman, August 1919. The wording reads ‘The future is in the hands of the woman: What will she sow?’

p.71

Tractor driving. (Sparsholt College Library archive)

Ploughing with horses. (Sparsholt College Library archive)

p.72

A Sparsholt bull. (Sparsholt College Library archive)

Horticultural students with the apple harvest. (Sparsholt College Library archive)

p.77

‘Members of the Women’s Land Army being instructed in the art of thatching.’ (Getty Images, serial no. 1297440939; Photo by Reg Speller)

p.80

Women’s Land Army membership card issued to Isabella D.S. Waddell – 25 July 1940 (front and reverse).

p.81

An ‘Australian Sunshine Stripper harvester’ being demonstrated at Mr W.H. Wroth’s farm. Bunty Horniblow is the person standing on the machine. (Reproduced with thanks to Bruce and Gill Horn)

p.83

Recruitment poster, 1941.

p.85

‘The Land Army Growing Vegetables for the Navy’, showing a gang of land girls harvesting and packaging cabbages into wooden crates with the Isle of Wight in the background. (Picture by Archibald Standish Hartrick, courtesy of the Garden Museum)

p.86

Plan for ‘Agricultural Workers’ Hostel’ at Colden Common, Brambridge, submitted to Winchester Rural District Council, 1 August 1941, approved 28 August 1941.

p.87

Dining room at a Women’s Land Army Hostel. (Painting by Evelyn Dunbar, 1943)

p.90

Redenham House, Weyhill, Hampshire, circa 1945. (Lent by Redenham House staff)

Memorial tree in Redenham House grounds, planted by Gwen and Maurice Raggett.

Memorial plaque provided by Gwen Raggett in 1990, at the base of the tree.

p.92

Hostel built for the land girls at Hale Nursery, near Fordingbridge.

Land girls in their familiar uniform at Hale Nursery, circa 1945.

p.100

Timber Corps camp accommodation.

p.103

Leaflet (1943) featuring Amelia King, issued to draw attention to racial discrimination.

Land girls at Frith Farm, Wickham, including Amelia King (circa 1944). (Wickham History Society)

p.110

Land girls driving tractors at a Rally, Southampton, 1946.

p.113

‘Release Certificate’ for Jeanne Mason, 5 August 1947.

p.117

Membership Card, Women’s Land Army Old Girls Association, Hampshire and Isle of Wight; Mrs D. Bowman, 29 March 1951. (HRO ref; 50M90/6) Final Reunion of Women’s Land Army Old Girls’ Association, Hampshire and Isle of Wight, 27 April 1968.

p.119

Programme of the ‘Hampshire Service of Thanksgiving to recognise the contribution made by members of the Women’s Land Army and Women’s Timber Corps’, 7 May 2009.

p.121

Women’s Land Army and Women’s Timber Corps Memorial. Unveiled by HRH Countess of Wessex, 21 October 2014. (Egghead06, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

p.126

Gwen Raggett, 1926, aged 17. (Copy supplied by GR)

p.127

Land girls, and officials, in front of the main entrance to Redenham House, 1947. Gwen is seated on the ground, second in from the right. (Copy supplied by GR)

p.130

Isabella D.S. Waddell in her Women’s Land Army uniform.

Abbreviations

NFU

National Farmers’ Union

‘War Ags’

War Agricultural Executive Committee

WI

Women’s Institute

WLA

Women’s Land Army

WNLSC

Women’s National Land Service Corps

WDRC

Women’s Defence Relief Corps

WTC

Women’s Timber Corps

Foreword

It is an honour to write a foreword to this book which highlights the tremendous commitment of some 240,000 women and girls who volunteered to join the Women’s Land Army to work on farms, in market gardens, and forestry, during the two world wars. They gave up their jobs and homes, often in urban areas, and left their families and friends for a life of manual work in the countryside. For many, this was a new work experience and lifestyle: milking cows, driving tractors, mucking out pigs, hauling timber with horses, and sleeping on bunk beds in hostels with basic facilities.

In making this personal sacrifice they helped boost the production of home-grown food and timber as part of the war effort to feed and support the nation. They responded to the nation’s hour of need, and the nation owed them an everlasting debt.

John Lander, the author, undertakes research into local history. He leaves no stones unturned in the pursuit of detailed information, as I discovered in his discussions with me as a former Principal of Sparsholt College, Hampshire, when he was researching material for his book on the history of the college, A Place of Transformation, published in 2022. This same approach is evident in researching the WLA during both world wars, nationwide as well as in Hampshire. He has traced surviving land girls as well as relatives of others who were in the Land Army, gathering information about their experiences. One land girl revealed that she was given the responsibility of driving a 3-ton lorry, perhaps before her 18th birthday, and another described her wide variety of roles; potato picking, milking and harvesting sugar beet were examples.

The book presents a detailed account of the work and living conditions that the volunteer land girls experienced, as well as the demands they faced doing land work as their contribution to the war effort. Some were also confronted by other social, prejudicial and economic challenges. A few farmers were reluctant to employ women, some applicants experienced racism when applying to join the WLA, and the wages paid to land girls were below those paid to men for the same work. Nevertheless, land girls were lauded by many for the work and commitment they had shown in replacing male workers who had left for military service.

On reflection, it seems likely that WLA workers had a much wider impact on society beyond their efforts to boost food production. Women working in the First World War led to the opening of the labour market and, eventually, to equal voting rights. Land girls employed in the Second World War showed that they were quite capable of doing work traditionally done by men, and thereby strengthened the case for equal opportunities and equal pay in the land-based sector.

Following the final parade commemorating the WLA in 1950, the Queen said that ‘the land girls had earned a noble share in the immense effort which carried our country to victory’. Details of that ‘immense effort’ are recounted in this book.

Dr Len Norman, PhD, MSc, BScPrincipal, Sparsholt College, 1970–1998

About the Author

A banker by profession, though a social historian by natural inclination, most of John Lander’s career was with one of the joint stock banks, culminating in an appointment as a Corporate Finance Director. He subsequently became a director of a publicly quoted company, and Director of Finance at an independent school.

In 1989, John embarked on Open University study, obtained a BA (Hons) and, following submission of a thesis entitled Tent Methodism: 1814–1832, was awarded a PhD in 2000. Since then, he has written over twenty-five books and papers published in specialist journals, mainly concerned with aspects of nineteenth- and twentieth- century Nonconformist Church history, and Cornwall’s teetotal movement.

In retirement, John became a governor of Truro and Penwith College, where he chaired its Finance and General Purposes Committee, served as Chair of Coastline Housing Ltd, Vice Chair of Cornwall Rural Housing, and as a non-executive director of the Royal Cornwall Hospitals (NHS) Trust.

Since moving to Hampshire with his wife in 2019, John has become Chair of Winchester Housing Trust Ltd, a provider of social and affordable housing, and a church trustee. While he was a governor of the Sparsholt College Group he wrote the college’s history, A Place of Transformation, which was published in 2022. It was while conducting the research for that book that John discovered the full extent of the Women’s Land Army, and the significant part the college played in the training of land girls.

Preface andAcknowledgements

One reason for writing about the Women’s Land Army (WLA) now is that in November 2025 the country will mark the 75th anniversary of its demobilisation in 1950. Recording the work of thousands of women and girls on Hampshire farms, in not one but two world wars, will remind us that while, understandably, we can become preoccupied with day-to-day pressures, let alone recognise traumatic events around the world, there will be an opportunity to recall the vital contributions that women and girls made to wartime successes by maintaining food production.

I came to realise the full extent of the valuable assistance WLA members gave to Hampshire’s farmers while researching and writing A Place of Transformation. From 1915 to 1918 and again from 1940 to 1944, the college’s curriculum of one-year courses was abandoned, and staff devoted their expertise to training women and girls for tasks undertaken on Britain’s farms.

Sparsholt College Library holds a wide range of primary material, Hampshire’s Record Office has many archival documents, and local newspapers frequently reported WLA activities. Population censuses, particularly the September 1939 Registration, a family history website, and the ‘Google’ search engine, have all been useful. Books referring to the national impact the WLA had on the country’s food production have been consulted. I have appreciated the assistance of the librarian at Sparsholt College for her ready willingness to help over several years, and for the cooperation of staff at Hampshire’s Record Office, the Hampshire Chronicle, and the Museum of English Rural Life, part of the University of Reading.

Possibly the most rewarding aspect of writing this book has been the fruitful and fascinating conversations in the homes of descendants of people with WLA involvement. Material has been rescued from lofts and other places, and their enthusiasm and willingness to tell me of their links has been greatly appreciated. The book’s endnotes make appropriate acknowledgement of the information they gave me. I’m grateful to the members of my family who gave me much needed help with IT matters and, yet again, to my wife for her support while I’ve been ensconced in my study, or out visiting record offices, libraries and people with stories to tell.

It is inevitable that as time goes by the number of former land girls able to impart their personal wartime experiences reduces. It has, then, been a moving privilege to meet with two elderly women who served in the WLA. In October 2022, I had a detailed discussion with a lady, born in 1929, who trained at Sparsholt and then worked as a land girl for several years from 1947. Elizabeth (Liz) Bridges (née Cheal), over lunch that she was determined to prepare, pressed me to write about the vital work undertaken by women in both world wars, and beyond. Sadly, Elizabeth died in August 2023, aged 94, and won’t see the end result of her request. And then, in December 2023, I met with Gwen Raggett (née Place), 97 years of age, who recalled with great clarity some of the highlights of her six years as a land girl. Gwen and her daughter-in-law have huge volumes of preserved documents that have been made available to me. This book is dedicated to Gwen and Liz who, among countless women and girls, diligently served their country and the county of Hampshire in arduous wartime land-based jobs.

Another reason for describing the work of the WLA is that it ‘is often referred to as the “Cinderella Service”, a pillar of the war effort that was taken for granted and insufficiently recognised – both during the conflict and afterwards’.1 Much more attention has been given to those women’s organisations that were directly associated with the armed forces, such as the Auxiliary Territorial Service, the Women’s Royal Navy Service, and the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force. Far less acknowledged are the contributions of land-based employees, working very long hours, performing hard physical work in all weathers, and often a long way from their homes. This book is intended, in a modest way, to put right that inadequate recognition. This is especially so in the light of claims, made with some justification, that Hampshire might have been the first English county in both world wars to begin the training and placing of women and girls into agricultural settings.

Part 1:

First World War, 1914–1918

1

Introduction

The contributions that WLA members made in maximising food production while large numbers of United Kingdom men served in the armed forces during the Second World War is universally acknowledged. Far less well known is that twenty-five years earlier the county of Hampshire was in the forefront of recruiting, training and placing women and girls in farms when it became clear that the First World War was not to be won within a few months. Many Hampshire residents, including prominent individuals, and staff at the Farm School, Sparsholt, played pioneering and crucial roles in addressing the urgent need to maximise home food production to offset reductions in imports.

The employment of women on farms in the period leading up to 1914 was not new. However, while the overall number of women in paid work nationally was steadily increasing, multiplying threefold between 1900 and the end of the war, that had not been the case in agriculture. At the time of the 1871 population census, 33,513 ‘girls and women were out-door agricultural labourers’, nearly 25 per cent fewer than the 43,946 ten years earlier.1 While the method of calculation probably changed over the decades, and comparison with previous censuses may be flawed, the extent of the decline was strikingly evident from the 1911 census statistics when just 13,245 females were recorded as ‘agricultural labourers’. In that year, only 8 per cent of England’s agricultural workers were female. Most of those were employed in the northern half of England, and a sense of the quite different position in southern counties can be gauged by knowledge that only 1 per cent of Hampshire’s agricultural labourers were female.2 As a detailed example, the 1911 population census showed that 2.6 per cent of all Hampshire labourers working in market gardens were female, but in Cheshire it was 17 per cent and in Lancashire 14.5 per cent.3

For many decades, there had been a growing reluctance of women to undertake arduous farm jobs. There was the ‘gradual disengagement of women from agricultural labour … under the impact of increasing mechanisation, specialisation, and the acceptance of the ideology of domesticity which frowned upon women’s labour and especially physical work.’4 A further factor was that wages paid to women employed on farms were normally less than half the rate paid to men, and substantially less than amounts earned by females in occupations in the more industrial parts of the country. The urgent need for women and girls to replace men on farms was prompted by three factors: the rapid enlistment of large numbers of men to join the armed services; significant reductions in quantities of imported food by sea; and the requisition of at least 600,000 horses that were the main source of power on farms, for transfer to the Western Front.

While single women were readily accepted as employees in many sectors, the subject of married women undertaking work in most capacities was controversial for many more years. ‘Marriage bar’ restrictions were lifted for the four war years because, by January 1915, 100,000 male agricultural labourers had already left to join the armed forces. They were, though, strictly reimposed in 1918 when widespread unemployment among men was predicted. The ban on married women teachers and BBC employees was lifted in 1944 but lasted for much longer in the civil service. While sustained pressures eventually led to the start of a steady process to allow women to take a greater share in contributing to the nation’s gross domestic product, the Foreign Service did not allow married women as employees until 1973.

2

Initial National Response to Labour Shortages on Farms

The First World War began on 4 August 1914. The grain harvests that year were expected to be excellent, and although many male farm labourers had already left their land-based jobs, no special need to employ more women had been identified. There was, though, encouragement for schoolboys aged between 11 and 14 to assist farmers in gathering crops during their summer holiday. By the end of the year, however, concern about labour shortages appeared. The campaign to attract more females to replace men began in earnest early in 1915, and continued spasmodically throughout the remaining war years. Even so, in 1915 and again in 1916, arrangements were made for serving soldiers to return to the United Kingdom for two weeks’ furlough in the late spring and up to four weeks in the main harvesting season. In the first of those years, a total of 12,525 men took advantage of the opportunities to have a break from the fighting and help with haymaking and grain harvests, although farmers had sought 19,000.1

The WLA was not formally established until March 1917. Three years before then, it had been intended to hold a government-sponsored Agricultural Education Conference to determine what actions should be taken to maintain food production. In April 1914, a parliamentary question enquired how plans for the conference were progressing, and whether women were to be co-opted to its membership, bearing in mind that one topic related ‘to women’s rural education’.2 The answer that the Board of Agriculture had still to appoint six more members suggested a strange lack of urgency given the deteriorating prospect of sufficient resources to maintain, let alone increase, home food production. The conference was finally held eight months later, in December 1914, but Lord Selborne, President of the Board of Agriculture, had to say in June 1915 that the official report of the meeting was still being prepared. Yet another eighteen months were to elapse before the WLA became a reality.

That delay did not prevent attempts by non-governmental bodies to attract women and girls to undertake general work on farms. A plethora of organisations emerged, mostly akin to present-day employment agencies, to recruit permanent farm employees, and others to help at peak times. Some were successful in persuading government to provide financial grants towards their initial costs, but otherwise no official support was forthcoming.

Among many organisations, the Women’s Farm and Garden Union, established in 1899 as the Women’s Agricultural and Horticultural International Union, had long advocated the benefits of limited female work on farms. In mid-1915, a year after the war began, the union reported that ‘since the outbreak of war, a large number of trained women had been placed by the Union in gardens and in farms’.3 Another body, the Women’s Defence Relief Corps, was formed in September 1914. It had one section that was, from the spring of 1915, mainly involved in providing temporary labour to pick fruit, harvest the hop crop and haymaking. The corps offered to supply ‘gangs of five or ten strong young women as harvesters’.4 It was felt that providing the women were healthy and physically fit, only three days’ training would be necessary, and that would be provided by the farmers for whom they worked. Although its advertising campaign sought to attract women, paying them a minimum of 18/- per week, the WDRC was constrained by shortage of funds, and had placed only 500 women by the summer of 1917. They came from a wide range of occupations, and most of them were living in London.5

One quasi-official organisation, set up in February 1916 after consultation with the Board of Agriculture, was the Women’s National Land Service Corps, assisted by a £150 government grant towards formal training. In addition to requiring ‘young, strong, educated women who can give their whole time … at ages between 18 and 35’,6 2,000 volunteers were wanted to provide temporary help to farmers for short periods in the growing seasons. In April 1917, the 900 permanent members of the WNLSC were offered the chance to join the WLA, but, to the intense disappointment of the authorities, only eighty-eight accepted the invitation.7 It seemed that while many women were prepared to undertake work for a few weeks in the spring and summer, they were not willing, or able, to commit for a longer period.

In the absence of official recognition, those efforts achieved only modest success. Perhaps recognising general irritation among people keen to move forward, Lord Selborne stressed in January 1916 that the employment of women was ‘of the greatest consequence to agriculture’ and that ‘upon the solution of the question depends whether agriculture is or is not going to rise triumphantly over its difficulties’.8