Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The authorised biography of Field Marshal The Lord Bramall, now a House of Lords cross-bencher, who continues to speak against the failure of successive governments to provide adequate support for the nation's security and argues for the much closer co-ordination of foreign and defence policy.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 575

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1996

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

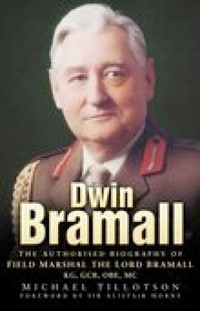

Dwin

Bramall

THE AUTHORISED BIOGRAPHY OF

FIELD MARSHAL THE LORD BRAMALL KG, GCB, OBE, MC

MICHAEL TILLOTSON

FOREWORD BY SIR ALISTAIR HORNE

First published in 2005

The History Press The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved © Michael Tillotson, 2005, 2013

The right of Michael Tillotson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9589 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Foreword by Sir Alistair Horne CBE

Author’s Note and Acknowledgements

List of Plates

List of Maps

Prologue

1

An Eclectic Boyhood

2

The Road through Goirle

3

Getting Around

4

Acquiring a Reputation

5

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

6

Operational Command

7

Leadership the Green Jacket Way

8

‘The Author and his Due’

9

The Application of Force

10

Divisional Commander

11

Hong Kong

12

Men and Money

13

Head of the Army

14

The Falklands War

15

Chief of the Defence Staff

16

Covering the Waterfront

17

Cross-bencher

18

The Fifth Pillar

Foreword by Sir Alistair Horne CBE

Somebody once remarked ‘Dwin has had a charmed life’. It is an observation that holds up on several levels. Anyone who has ever met him will recognise at once that special brand of personal charm, utterly uncontrived, as effective on women as on men. Michael Tillotson describes well that ‘slightly crooked, self-deprecating smile’ that greets acquaintances old and new. Perhaps strangely for so powerful a figure, Dwin genuinely sought to be liked – and so he was across a wide span of the Army, as well as in his social life, and in the Lords.

His professional career was, indeed, a charmed one – in at least two senses. At almost every point in it the Gods seemed to be smiling on Dwin, and pointing the way ahead to the very summit. From earliest days that seemed predestined. But reading Michael Tillotson’s vivid account of Dwin’s early life, as a young platoon commander in Normandy in 1944, one realises the full force of the ‘charmed life’. The last Chief of the Defence Staff to have seen action in the Second World War, Dwin landed with his motor platoon of the 60th in Normandy on D+ 1. He had several extremely narrow escapes in the fighting that ensued, and was wounded in the fight for Caen. By the time the battle had reached Belgium, Dwin was back in action. He had a miraculous escape stepping on a Schu-mine, which failed to explode, and ended the war with another wound and a well-earned Military Cross.

For Dwin, however, his experiences fighting the elite of the Wehrmacht in Normandy became more than the anecdotage of an old soldier. All through his career he reflected upon, and put to excellent use, what he had learned first hand about the particular skills of the Germans fighting a defensive battle, heavily outnumbered in men, material and air power. The lessons were particularly relevant to the kind of battle that the British Army might have had to fight (but, thank God, did not) against the Soviets in central Germany. When commanding his division in Germany in the 1970s it was partly his battle experiences that made him seek out the closest possible association with his opposite numbers in the Bundeswehr. He formed a very special relationship greatly beneficial to NATO.

He was, in every sense, a fighting and a thinking general – with the keenest of brains behind that bluff exterior. The papers he wrote in the 1970s left a permanent mark on British military doctrine and the art of leadership, impressing such hard-eyed critics as Professor Sir Michael Howard.

If there was any serious ‘blip’ in Dwin’s charmed professional life, it came – most regrettably – in the Heseltine era. Here his biographer pulls no punches. Rashly (one might almost say, foolishly) the hugely talented politician went ahead with his planned major reforms without consulting his Chief of the Defence Staff – or even keeping him informed. Tillotson speaks of ‘a conscious decision not to take the CDS into his confidence, but to present him with a fait accompli’, as does Heseltine in his autobiography Life in the Jungle. It seems the most extraordinary lapse: badly misjudging the timbre of the soldier with whom the politician was dealing.

During the Falklands War of 1982, Dwin was just completing his three-year tour as Chief of the General Staff. General Tillotson has some provocative, historical thoughts to offer here. Dwin had reservations about the risks associated with the landings and potential casualties of this hazardous undertaking. When the crucial, political decision to despatch the task force was taken, he was away in Northern Ireland. The Chief of the Defence Staff, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Terence Lewin, was visiting New Zealand, and also out of town was the Chief of the Air Staff, Air Chief Marshal Sir Michael Beetham – whose reservations about lack of air power complemented Dwin’s. So it was that Prime Minister Thatcher’s resolve was pre-eminently based on the forcefully positive (and, in the event, most courageous) advice of the more hawkish First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Henry Leach.

If Dwin had been present, his advice would almost certainly have comprised elements of caution. Now suppose he had been Chief of the Defence Staff at the time; might his advice have swung Thatcher against even sending the task force? It is an interesting speculation; certainly history would have taken a different course. But, as Dwin quickly appreciated, even if a political solution was favoured, a task force would be needed to project the requisite power in the South Atlantic, and once it had arrived off the Falklands and with no political solution by then in sight, then the military risks associated with repossession of the Islands would have had to be faced.

The Army was far from being the only strand in Dwin’s amazingly full life, and in it he was fortunate to be supported – very quietly, but nonetheless forcefully – by a wonderful wife, Avril. He was a painter, and a passionate (performing) cricketer. His energy in fund-raising, and getting things done, as Chairman of the Imperial War Museum was legendary.

Whenever he got up to speak, whether in the Lords or at public meetings, his was (and, happily, still is) always the voice of authority and good sense. I for one always sat up and listened. What a pity it was that the present government was not of the same mind when Dwin spoke out so vigorously against the war in Iraq. Here he echoed in a letter to The Times Field Marshal Templer’s question before the Suez operation, ‘Of course we can get to Cairo, but what I want to know is what the bloody hell do we do when we get there!’ Long may his voice be heard in the land.

It is indeed an honour to be invited to contribute a foreword to a fine biography of such a great soldier and human being.

Alistair Horne

Author’s Note and Acknowledgements

The question most frequently asked while I was working on this book was whether I found it difficult to write the biography of someone still very much alive. A certain self-discipline has been required, of course, and I may have made rather more provision for reading between the lines than might otherwise have been the case, yet I have not felt in the least constrained in what I wished to convey. More than half a century’s friendship with Dwin Bramall brings an assurance of its own, as well as an ability to argue the facts as well as the precise words to describe them. In consequence, the work has been accompanied by our customary informality and humour.

One of the Field Marshal’s well-known traits is his deliberate and quite shameless indiscretion, not – of course – over matters of national security but when he wishes to test opinion over something that is not yet fully in the open. He and I agreed that his commission to me to write the book should be kept under wraps, at least until I had got most of it done, and not one of those to whom the secret leaked has bothered me with a view to helping before being asked. I wish to thank all of them and especially those who, when they were asked, made such valuable contributions, whether they were just short but telling anecdotes or particular and well-informed views on an event or strand of policy.

I consequently wish to thank for their help on the purely military aspects of the story: Major-Generals John Badcock and Ian Baker; Brigadier Graham Binns, Lieutenant-Colonel Peter Blaker, Major-Generals Patrick Cordingley and Tony Crowfoot, Captain Guy Crossman – in connection with the expedition to Kufra and desert navigation; Major-General Len Garrett, Colonel Colin Groves, Brigadier Harry Illing, Captain Robin Lewin, Lieutenant-Colonel Jan-Dirk von Merveldt, Brigadier Roger Plowden, Colonel The Viscount Slim, Colonel Alan Steel, Lieutenant-General Sir Christopher Wallace and Major Sir Hereward Wake, Bt.

For matters concerning the period Lord Bramall spent as Commander British Forces Hong Kong, I am indebted to Bim and Mona Davies for their recollections of that international village while he was there and to Clinton Leeks for his research into the continuing problems associated with the Vietnamese refugee boat people.

For accounts of events in or near Whitehall, I wish to thank Lieutenant-General Sir Derek Boorman, Major-General Harry Dalzell Payne, General The Lord Guthrie of Craigiebank – for his good-humoured account of a brief altercation with the Field Marshal; Alistair Jaffray, Deputy Under Secretary of State in the Ministry of Defence 1975–84 and General Sir Edward Jones – for a recollection while Black Rod. I am especially grateful for Lieutenant-General Sir Maurice Johnston’s thorough survey of events in which the Field Marshal and he were involved over several years in various appointments, to the late Air Vice-Marshal John Miller, General Sir John Stanier, General Sir Michael Walker, currently Chief of the Defence Staff, and Admiral Sir John ‘Sandy’ Woodward.

Research into ‘across the waterfront’ activities of the Lord Lieutenant of Greater London require my gratitude to George Gordon-Smith, the invariably busy but equally patient Clerk to the Lieutenancy, Dr Alan Borg and Robert Crawford, successively Directors-General of the Imperial War Museum, and to Suzanne Bardgett, Christopher Dowling, Penny Ritchie Calder and Julia Mills of the Museum staff; Sir David Plastow and Gerald Boxall, both formerly of Vickers Defence Systems, to Dennis Silk for matters appertaining to Dwin Bramall’s period as President of MCC and as a Governor of Radley College, Sir Michael Pike and Justin Staples, past and present Chairmen of the Travellers’ Club.

I also acknowledge the benefit I have received from reading The Struggle for Europe by Chester Wilmot, The Battle for the Falklands by Sir Max Hastings and Sir Simon Jenkins, Life in the Jungle by Lord Heseltine, Here Today Gone Tomorrow, frankly and engagingly written by Sir John Nott, and H. Jones, VC: The Life and Death of an Unusual Hero by General Sir John Wilsey and The Annals of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, volume VII, by Major-General Giles Mills. I have of course drawn on the works of many other distinguished authors too numerous to mention. I am immensely grateful to Lord Bramall for allowing me access to his letters, papers and tape recordings as well as to literally hundreds of photographs illustrating his career and his and Lady Bramall’s lives.

I have greatly valued the help of Lieutenant-Colonel Peter Chamberlin, Regimental Secretary of the Royal Green Jackets, in providing contacts and information throughout the research and writing of the book, and the advice, patience and exhilarating enthusiasm of everyone at Sutton Publishing associated with the book during the difficult period of ‘putting it to bed’. I am also very grateful for the tactful and helpful suggestions of Elizabeth Teague, my copy editor. If I have inadvertently omitted to thank others, then I hope they will recall my appreciation at the time and forgive me.

I wish to acknowledge permission from Her Majesty’s Stationery Office for permission to base Maps 1 and 3 on maps the Office supplied to B.T. Batsford Ltd that appeared in The Battle for Normandy, by Eversley Belfield and H. Essame, published in 1965, and the Celer et Audax Club for permission to reproduce Map 4, taken from the Annals of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, Volume VII, by Major-General Giles Mills.

My intention has been to record, inform and, most important of all, to provoke fresh thinking on those aspects of our foreign and defence policy that continue to give Lord Bramall concern.

Michael Tillotson

Wylye, Wiltshire

List of Plates

1.

Major Edmund Bramall

2.

Bridget ‘Bryda’ Bramall

3.

‘Messenger Boy’ with his brother Ashley

4.

Dwin with Mollie Neville in the early 1930s

5.

Juvenile batting competition, 1934

6.

Varnishing Day, Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, 1940

7.

Private in the Home Guard on his seventeenth birthday, 1940

8.

Member of the Eton XI, 1941

9.

Scoring the winning run in the Eton v. Harrow match, 1942

10.

Near Weert, 1944

11.

Receiving the MC ribbon, 1945

12.

Acting Major Bramall, 1946

13.

Hiroshima, 1946

14.

Home from the war

15.

Wedding Day, 16 July 1949

16.

The newly weds

17.

Avril with Sara aged five and Nicolas aged four

18.

During the expedition to Kufra, 1957

19.

The Brandenburg Gate, 1961

20.

Commanding Officer, Borneo, 1965

21.

With the Soviet Military Attaché on Exercise ‘Iron Duke’, 1968

22.

At the Darmstadt Ski Meeting, 1972

23.

Arriving in Hong Kong met by Major-General ‘Bunny’ Burnett, 1973

24.

Flagstaff House, Hong Kong, 1973

25.

With Gurkha officers, Hong Kong

26.

With HRH The Prince of Wales and The Right Honourable John Nott MP, Church Crookham, 1981

27.

The Chiefs of Staff during the Falklands War

28.

With The Right Honourable John Nott MP and General Sir Frank Kitson and the QE2

29.

With his brother Sir Ashley Bramall

30.

With The Right Honourable Michael Heseltine MP and General Jack Vessey

31.

Lady Bramall during an official visit to Italy, 1982

32.

Sara and Nicolas at Sara’s wedding, 27 June 1987

33.

Painting in retirement

34.

As President of MCC, 1988–9

35.

With grandchildren Charlotte and Alexander

36.

In Belize with the SAS Regiment

37.

Receiving the Inter-Faith Gold Medallion, 2001

38.

As Lord Lieutenant with Her Majesty The Queen, 1995

39.

Knight of the Garter, walking in procession with the Duke of Wellington KG

40.

The Lord Lieutenant of Greater London in his office

List of Maps

Map 1.

Operation Epsom, June 1944

Map 2.

The expedition to Kufra, 1957

Map 3.

Operation Goodwood, July 1944

Map 4.

Central Sector of West Brigade area, 1965

Map 5.

Tawau Sector of East Brigade area, 1966

Map 6.

The Falkland Islands

Prologue

One of the generals in the bar was getting some good-natured ribbing. It was the biennial conference for infantry commanders at the School of Infantry at Warminster, with a fair number of senior officers present. The butt of the banter did not match the popular image of a general. Of medium height and stooping a little, he had a pale, humorous face with a rebellious lock of hair falling over his forehead, which he only occasionally troubled to push back.

It had just leaked out that Major-General Edwin Bramall, known as ‘Dwin’ since boyhood, was to be promoted at the end of his command of the 1st Armoured Division in Germany to become Commander of British Forces in Hong Kong. This meant he would skip a second appointment as a major-general and be a full step ahead of his contemporaries, so some of the badinage may not have been quite as jocular as it sounded.

The principal reason behind his advancement lay nine years ahead. At this time – the early 1970s – the three armed services provided the Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS) in rotation, the individual stepping up from having been the professional head of the Navy, Army or Air Force. It was therefore important for each service to monitor the situation to ensure a man of the right calibre was available when the time came. The then head of the Army (Chief of the General Staff) General Sir Michael Carver, a man of powerful intellect and relentless efficiency, would shortly become CDS himself. He had in mind two young generals to succeed to the top post nine years ahead but recognised that he would have to force the promotion pace for one of them. After visiting both at their respective divisional headquarters in Germany, he decided on Bramall. But by announcing only his selection for Hong Kong and consequent early promotion, Carver was keeping options open for anything unexpected; the message was nevertheless clear to read.

Even as a young officer, Bramall was widely known in the Army. This was due in part to his ability but more to his spontaneous friendliness. His slightly crooked, self-deprecating smile would greet acquaintances old and new, conveying an impression of joint complicity in some enterprise in which they could safely share confidence.

He had no time for affectation, so his superiors grew to recognise his friendliness as a bonus to his searching mind. Not only did he think clearly and constructively, but the warmth of his approach could persuade others to discard prejudices for ideas they would otherwise reject without a second thought. He was more sombrely dressed than most others at the Infantry Conference dinner in 1973. He wore the ‘mess kit’ of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps – the 60th Rifles – more usually known simply as the ‘60th’. It was of the darkest possible green, appearing almost black, with black buttons, a soft rather than starched shirt and no badges of rank. This last idiosyncrasy indicated there was no rank within the 60th mess, where all officers were equal – a band of brothers.

At the time of his battalion command on active service, Bramall wrote a pamphlet entitled ‘Leadership the Green Jacket Way’ and later, having commanded a brigade, a wide-ranging politico-military thesis: ‘The Application of Force’. Both indicate deep but liberal-minded thought about his profession and, the thesis in particular, on the humane and moral issues with which those who make war are faced and would increasingly face in the future. There are two opinions on these writings and the many lectures and informal talks he gave. The first claims him unequivocally as an original military thinker with a mind free of bias or prejudice. The second accords him the facility of a good listener, a detector of points for development and expansion on the ideas of others. The truth lies not between these two extremes but in the evidence that he fulfilled them both.

In seeking the central issues of his philosophy, one would not go wrong in settling on ‘humanity’ and ‘candour’. When invited as Chief of the General Staff to speak at the Royal United Services’ Institution on ‘The Future of Land Forces’ in early 1982, he began, ‘I don’t have to remind this audience that war settles nothing. It may have its moments, it may bring out the best in some people but, apart from the suffering it causes in human and economic terms, it usually creates more problems than it solves.’

Most significantly, perhaps, in the same address he questioned whether in the closing years of the twentieth century full-scale war could still be regarded as a rational extension of a country’s foreign policy. He concluded that it might be if full-scale military force could achieve the political objectives in a matter of days as, for example, in the Israeli pre-emptive war of 1967, but he questioned whether opposed, closely contested and therefore prolonged military conflict could any longer be regarded as a legitimate means of pursuit of a country’s foreign policy goals.

Until reality dawned following the Suez débâcle of 1956, British defence chiefs had struggled to balance NATO treaty commitments with demands for ships, troops and aircraft to deal with problems in the residual empire or in support of such commitments. Many of the second category persisted after Suez, but national defence responsibilities were grouped under two headings: Priority 1 – NATO; and Priority 2 – outside the NATO area. Such was the cost of maintaining the former that Priority 2 commitments had to get by almost entirely with crumbs falling from the NATO table.

That table stood on four ‘pillars’: nuclear deterrence, defence of the (United Kingdom) home base, a contribution to defence of the NATO Central Front and, fourth, defence of the Eastern Atlantic. Struggle for financial resources in support of the different pillars caused two rival groups to emerge: one locked into a ‘continental’ NATO strategy and the other arguing that the more traditional ‘maritime’ strategy would provide flexibility outside the NATO area, and so be closer to the national interest.

In 1982, the Argentine invasion of the Falkland Islands saved supporters of a maritime strategy from the extinction that would have resulted from implementation of the 1981 Defence Review proposals to reduce the Royal Navy to an anti-submarine force only. Although the war was characterised as a ‘one-off’, without any perceivable replay elsewhere in the world, the risks of relying on armed services equipped, located and trained for operations in support of NATO only were laid out for the world to see. On the brink of taking over as Chief of the Defence Staff, Bramall was handed an example to show that even though the Soviet Union presented the principal threat, a balance between a continental and a maritime strategy must be maintained. From that point he could argue for extra resources for Priority 2 operations in addition to allocations in support of the four pillars.

More broadly, the foreign policy and intelligence failures which led to the Falklands War were sufficiently apparent for him to argue for one coherent framework for development of a dynamic foreign policy to take account of defence problems and potentialities. Privately, he dubbed this policy the ‘Fifth Pillar’. Close cooperation by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Ministry of Defence would be critical to formulating the UK’s strategic and economic interests; abroad it would be a question of ‘helping our friends to help themselves’. Six years after Field Marshal Bramall ceased to be CDS, collapse of the Soviet Union rendered invalid three of the four pillars of British defence policy. Defence of the UK home base remained, but the way was cleared for adoption of his concept of ‘indirect military influence’ abroad or, as he originally named it, the ‘Fifth Pillar’.

Although no doubt he would have chosen to spend more time at his easel or in his garden, continuing demands for his talents and time after he had relinquished the post of CDS gave him scant scope for either. Active membership of the House of Lords, Lord Lieutenant of Greater London, Chairman of Trustees of the Imperial War Museum and President of MCC brought him the challenges and the controversy on which this extraordinarily dedicated and energetic man thrives.

CHAPTER ONE

An Eclectic Boyhood

There is a Chinese saying that the greatest gift a child may have is to be born in interesting times. When Edwin Noel Westby Bramall was born on 18 December 1923, Adolf Hitler was making his first impact as a political force on the streets of Munich and Joseph Stalin had survived Lenin’s dying attempt to remove him from the post of General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, leaving him at the centre of power in Moscow. In succession, these two men and Stalin’s legacy were to be the dominating influences in world affairs during much of Bramall’s professional life. They were indeed interesting times.

Edwin Bramall was born just before Christmas in the small town of Rusthall in Kent, where his mother was visiting her own ailing mother who lived nearby. Although an older brother had been born eight years earlier, Bridget Bramall, always known as ‘Bryda’ or, after her marriage, as ‘Billie’, was by that time in her late thirties and so, by the norms of the day, his arrival created something of a stir in the family. As it happened, their GP had advised an abortion, but her natural way of overruling even the best-intentioned advice, declaring ‘I want my baby’, led to his safe delivery. He subsequently enjoyed a life of good health, unlike his brother, who was slightly delicate during his schooldays. The name ‘My Baby’ stuck and a little over half a century later the staff in the front office of the Chief of the General Staff were surprised by a call from an elderly lady demanding, ‘I wish to speak to My Baby.’ ‘Mother,’ said the Chief when he picked up the phone, ‘you really cannot say that sort of thing. Everyone will think we are stark raving mad.’ But she declined any rebuke, stating firmly, ‘Why not? You are My Baby.’

Despite being married conventionally enough in Salisbury Cathedral after a whirlwind courtship during the First World War, the Bramall parents were a distinctly disparate couple. Although Bridget was from an impoverished aristocratic family and lacked any formal education, she was well informed, highly intelligent and fiercely radical. Energetic and extremely strong-willed, she wished to live nowhere other than Kensington or Chelsea. In contrast, Edmund Bramall was of solid trade stock from the Potteries. He was what we would now describe as ‘laid back’ – an easy-going countryman with a great love of sport of all kind, both country pursuits and team games. He was good at them too, once playing roller-skating hockey for England while up at Pembroke College, Cambridge, an achievement to which Mrs Bramall managed not to give too much publicity. He was a good horseman and a keen shot, but utterly devoid of ambition, tending to drift into things rather than making any definite plan for his life.

There was never any doubt as to the dominant partner, which suited both personalities admirably. The sons, although separated by eight years, were quick to realise that their mother required, indeed demanded, instant agreement with the judgements she invariably took on every conceivable issue of the day. Until the Second World War intervened, the family was based in London, making only brief sorties to the paternal grandparents’ large and comfortable house in Sussex.

On leaving Cambridge, Edmund Bramall had gone off to war in 1914 in company with virtually all his generation. He was commissioned into the Royal Artillery and served first as a forward observation officer, then as a battery captain and finally as a battery commander on the Western Front in France. He was at the battle of Ypres, on the Somme, was twice wounded, and contracted rheumatic fever. Subsequently, finding gainful employment in the 1920s proved none too easy, not least because of his wife’s insistence that certain types of job were not among those a ‘gentleman’ should undertake, which inconveniently were those he would have found easiest to master. In consequence, between the two world wars, Edmund had no earned income, but relied entirely on that from shares in the family business to meet the needs of a wife who was an accomplished spender.

The family business was cotton growing in the Fayoum in Upper Egypt. Edmund Bramall’s grandfather had married into the family of Sir Robert Peel, the MP for Lichfield, later Prime Minister and responsible, when Home Secretary, for the introduction of the modern police force. The Peels were already one of the great English cotton growers in Egypt, and Edmund’s father had gone out to Egypt as a young man, first to be involved in construction of the first Aswan Dam and then to enter the Peel cotton-growing company. This prospered, making a considerable amount of money for the family until the business was sequestrated by President Abdul Nasser in 1956.

Through these earlier events the Bramall family became closely connected with Egypt. Edmund’s parents had brought up five children in the rigorous climate of Beni Suef (Bani Suwayf) in central Egypt, where Edmund was born. As the eldest son, he was the obvious choice to take over running the business from his father. Bryda, however, refused to go to Egypt, other than for the briefest possible visits, so responsibility passed to Edmund’s youngest brother, a charming and fun-loving man who had nearly as many wives as he owned horses. This situation led Edmund to opt out of the family business to an increasing degree and that family to question whether he had made the right choice of wife, who had such a different inclination.

For her part, Bryda applied her restless energy and innovative brain to hatching money-making schemes that, with a little luck and a partner of greater business acumen, might have significantly altered the family fortunes. She started a car-hire company, specialising in yellow Rolls Royce cars, and a ‘boys’ kit bureau’ for cast-off boys’ school clothing that, when renovated, could be sold second-hand to save parents significant sums. She backed ‘fix-o-quick’ patent furniture for alfresco meals and holiday homes capable, like the furniture in Nelson’s men-of-war, of being taken to pieces and quickly reassembled, and a home-made jam and marmalade business marketing under the name ‘Simple Simon’. Although the ideas were good, none of the ventures came to anything and the family coffers got lighter by the month.

From the late 1920s to the start of the Second World War, the Edmund Bramalls were obliged to move steadily down market as their money ran out. In 1939, they sold their house in the King’s Road, Chelsea, for £3,000 and managed to hang on in London only by relying heavily on Edmund’s ever-tolerant parents, who consistently bailed them out, in particular over the children’s education.

Dwin went as a day boy to Gibbs School in London, presided over by the patriarchal Charles Gibbs. The teaching was excellent and the games, played on the Harrods ground at Barnes, well coached and enjoyable. His brother Ashley had been there before him and, although not good at games, was academically very bright and benefited greatly from the school before going on to Westminster. Dwin excelled in mathematics under the encouragement of Mr Cummings the maths master, who had played rugby football for Llanelli. Although he was of medium stature, the young Bramall revelled in all games. When he left Gibbs at Christmas 1934, Cummings gave him a copy of Soccer by David Jack inscribed, after complimenting the young sportsman on his ‘wielding the willow at Barnes or feeding his forwards and in the boxing ring’, with the hope: ‘May it be said that your life’s battles were won on the playing-fields of your first school.’

Dwin was enjoying Gibbs but, probably sensibly as he would have to progress to boarding school, his parents took him away to go to Elstree School, Hertfordshire, as a boarder. He was ten, not seven or eight, which was often the normal age for British children to go away to school, so was able to brush off home-sickness and adjust to boarding-school life quite easily. Academically, he was no better than average, giving his greatest enthusiasm to sports and games. He captained the school cricket side and made two centuries not out in his second season.

Here again, he came into contact with some fine schoolmasters of considerable academic and sporting distinction. These not only kept him up to the mark in both aspects of school life, but provided inspiration. Coming off the rugby field on one occasion, he was mortified to hear a much-respected master who was an Oxford double-blue and a classical scholar say, ‘Bramall, you funked that tackle.’ Ten years later, when he was about to land on the beach at Normandy, he could, as he put it, hear that voice again and thought to himself, ‘My God, I’d better not do that again.’

He had hoped that his parents would choose Harrow as his public school, as Elstree was the preparatory school for Harrow and many of his friends were due to go there. His father had been at Sherborne, but stories of what new boys had to endure there had put his mother off and since, despite her radicalism, she was also a bit of a snob, she chose Eton. Once he was there, his mother became quite obsessive about the school, using – in her ever-simplistic way – various yardsticks to assign public figures to either the Hall of Fame or the Chamber of Horrors. For example: ‘If you were black you got good marks, if you were a black Socialist (not unusual), you got better marks still, but if you were a black Socialist Old Etonian (perhaps a little more rare) you got the best marks of all!’

In fact Bryda Bramall did her younger son a great service by sending him to Eton. He revelled in the privacy of a single room, and the unique opportunity that Eton provides for developing personality and real responsibility given progressively in running the school’s activities. He was in a house under a caring housemaster with whom he got on extremely well, and he entered into many of the wide range of activities available. He got his House Colours for the field game, was elected to the Library (House Prefect) and became Captain of his House and a member of ‘Pop’ (School Prefect); he fenced, played fives and cricket for Eton and eventually captained the school XI. He was an underofficer in the Officer Training Corps and became a sergeant in the Home Guard.

The drawing schools allowed him to develop his painting skill, and he had two pictures hung at the Royal Academy while at Eton. Afterwards, he was told by the drawing master that this gave the place some much-needed respectability in the eyes of the headmaster, who had suspicions as to what vice and perversions went on in the music and drawing schools but was reassured by the presence of the Captain of the XI. He read a paper on Wagner and Verdi to the curiously named Junior Archaeological Society and thoroughly enjoyed a life he found full of variety and interest.

If Eton had any penalty for him, it was living together with boys from rich and aristocratic families, some of whom – until the war brought petrol restrictions – were able to visit their sons in excessively smart cars. The Bramall parents, in somewhat distressed circumstances, would turn up in a rather battered second-hand car. This was conspicuous enough, but worse might come in the form of a seven-months’-pregnant sister-in-law, together with the cleaning lady and window cleaner whom his mother, in her personal obsession over Eton, thought would benefit from seeing the school for themselves. He made no protest, welcoming all without embarrassment and perhaps unconsciously preparing himself for the future.

After the largely ignored wake-up call of Munich a year after Bramall had arrived at Eton, war was declared, adding a wholly new element of excitement to all the other activities. With air-raid warnings sounding almost every night, the boys often slept in shelters constructed in the gardens and manned firefighting equipment to douse fires started by incendiary bombs that penetrated the roofs of some of the buildings. One evening, a German bomber jettisoned two high-explosive bombs in the very heart of the school, destroying the houses of the senior music master and the organist, as well as flattening a large part of the school hall.

The period 1940–1 was one of great national stress, with invasion by sea and parachute landings regarded as inevitable until Germany turned the other way and invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941. Everyone felt in the front line, not least the older boys serving in the local Home Guard with Windsor Castle so close and an obvious target in any parachute attack. The provost and headmaster dismissed any notion of evacuating the school to some more remote part of the country, as many in London and close to the south coast had been obliged to do.

Bramall’s five years at Eton ended on a series of high notes. The cricket team he captained never lost a match, beating both Harrow and Winchester. He was selected to captain the Lords Schools against the other public schools at Lords in 1942, the opposing side being captained by the formidable Trevor Bailey, later to play for England. He was subsequently Bailey’s vice-captain in the overall Schools side to play the MCC. On the academic side, he achieved his Matriculation.

There had been disappointments and setbacks, of course. He had had to ‘fag’ for power-conscious older boys, but did so without feeling humiliated. He had been beaten for things that he regarded as scarcely his fault, but he was not bullied or abused in any way. Looking back many years later, he conceded that he was not sexually precocious in any sense, rather the opposite, which was not unusual at that time. His energies were directed principally towards the sports field, and, as this brought success, his schooldays were exciting and satisfying, with such disappointments as there were providing a valuable insight into the world outside.

His mother continued to be the dominating influence in his life throughout his schooldays, encouraging and supporting him in work and sport. She never allowed her uncertain health to interfere with attendance at special days, plays or matches in which he took part. Happy schooldays were not by any means the only things for which he had cause to be grateful to his mother. She was difficult to be with at close quarters, but evoked sincere admiration and affection in the many she befriended from a distance and she knew how to treat people. With her immediate family, she invariably had her own agenda, expecting everyone, including her husband and later her daughters-in-law, to conform to her ideas, virtually without question.

It has to be acknowledged that Bryda Bramall was manipulative in all she did, never shrinking from using illness – sometimes of an unrecognised nature – to get her way. A favourite was temporary paralysis of the legs if thwarted in any family issue. There is no doubt that Dwin learnt a great deal from her, not least that everyone has importance, whatever their role in life. She could also see herself for what she was and recognised that in a somewhat tempestuous household her children needed an element of stability outside the family. In Dwin’s case this took the form of a friend of Bryda’s – Molly Neville – whom she arranged to look after him when still quite young and into adolescence. She was calm and understanding and he looked to her for support in any family or personal crisis that might prove too difficult to handle alone.

His mother also took pains to develop a cosmopolitan outlook in her children. Having been a difficult child herself, with relatively impoverished and remote parents – her father was sixty when she was born – she had been sent with her friend Molly Neville to stay with a rich and well-connected aunt who had houses in Fiesole, overlooking Florence, Montreux in Switzerland and Heidelberg in Germany. These places left a lasting impression on her, and, in consequence, Dwin and his elder brother travelled a good deal before the war to Paris and on walking tours in the Rhineland, as the Nazis were coming to power, and in Switzerland. They were taken to Madrid to view the pictures in the Prado, giving Dwin a great incentive to widen his knowledge of Europe and to take an interest in languages, not least because whenever Bryda wanted to say something to her husband she did not wish the children to hear she spoke in Italian.

Bryda had dabbled in both painting and sculpture and this had stimulated Dwin to try his hand and, from preparatory school onwards, he practised in oils and watercolours whenever time allowed. Success came early with the acceptance of two of his oils, Sloane Square and The Ballet, by the Royal Academy of Arts for the Summer Exhibition of 1940, when he was sixteen. For him, painting was a relaxation rather than a need to capture a scene or a particular moment in his own hand. He continued to paint throughout his life, exhibiting occasionally but never again at the Royal Academy. He was always intensely interested in other people’s paintings, whether their own work or just owned, and his eye would be scanning the walls of a house he entered for the first time from immediately after his hostess’s greeting and, given half a chance, he would tuck her arm in his, leaving other guests to look after themselves, while he walked her round her own drawing room to view the pictures.

As his time at Eton drew to a close in July 1942, the question of a career came into family discussion. Murmurings about the military met with no maternal enthusiasm whatsoever. His mother hated the war and would have liked him to become a physician, to which he was not averse, yet, other than postponing it for six months by taking a short wartime course at university, there was really no immediate alternative to military service. In view of his artistic and musical interests, it is perhaps surprising that the young Bramall should hanker after a military career. Nor was it possible to attribute his enthusiasm only to the current national and international situation or to the very obvious presence of the military all over the country. It went back to nursery days when he and his brother would work out systems for the tactical deployment and use of their model infantry and cavalry soldiers.

The solution to the problem of not causing his mother needless distress lay at hand in the form of allowing his name to go forward for the place at Christ Church College, Oxford which he had earned at school, to be taken up at the end of hostilities, in the meantime volunteering for the military service for which he would be very shortly called up in any case. Bryda was fully alert to this situation, as when war came her husband had rejoined the Royal Artillery and served in England in various gunner regiments, including a coastal artillery battery on the Lincolnshire coast during the invasion scare. She had followed wherever he was posted, living in rented accommodation, boarding houses or small hotels, where she was joined by Dwin from Eton during school holidays or breaks when not required for Home Guard or airraid precaution duties or voluntary shifts in an aircraft-manufacturing factory in Slough. Temporary stability was achieved only when Major Edmund Bramall was appointed personal assistant to the Commandant of the School of Artillery at Larkhill.

July 1942, when Dwin Bramall left Eton to enlist, was one of the lowest points in the war for Britain. On Christmas Day of the previous year, Hong Kong had fallen to the Japanese, followed by the much graver strategic loss of Singapore in February. The German 6th Army was a mere forty miles from Stalingrad, U-boats were masters of the Atlantic and, in August, the unreadiness of the Allies to return to the Continent would be revealed by the severe losses sustained in the Dieppe Raid. The turning point of El Alamein was still three months away and even then, as Winston Churchill put it in his Mansion House speech, ‘This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.’

CHAPTER TWO

The Road through Goirle

Dwin Bramall first experienced the ferocity of German retaliatory action in the Normandy beachhead in June 1944. He was spared the nerve-racking run-in through the mined breakers on the early morning of D-Day, but saw the dead and wounded from the first wave of the assault being carried from the landing craft into which he and his platoon were about to embark.

He had volunteered for military service immediately after leaving Eton, having already shown military aptitude by becoming a cadet under-officer in the school Officer Training Corps. But this gave no advantage on enlistment, beyond a fundamental grasp of the army system, infantry weapons and the tactical use of ground; as for everyone, his training had to begin afresh.

Although accepted at interview as suitable for a commission in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps (60th Rifles), he joined the regiment as a rifleman. This was something he was to value all his service, as it provided his first insight into the world of young men from all parts of British society and the harsh realities of army life. He found himself one of a small band of cloistered public schoolboys thrust into the midst of a larger bunch of very street-wise cockney lads communicating in a cacophony of four-letter words, but whose worth they quickly learned to appreciate and who became their mates. He also learnt that life was not always fair and what it was like to be on the receiving end of what sometimes appeared to be bloody silly orders that had to be obeyed if discipline was to be maintained.

Raised in 1755 on Governor’s Island, New York, from American settlers of Maryland, Pennsylvania and Virginia, together with Hanoverian and Swiss mercenaries, initially as the ‘62nd Royal Americans’, the regiment had an unorthodox approach to soldiering. Its original role was to fight the French and indigenous Indians along the banks of the Ohio river. Forsaking the traditional red coats and close-quarter drill in battle, which had contributed to General Braddock’s defeat at Fort Duquesne in 1755, they moved quickly in loose formation, concentrating on accurate shooting. When working with other units, the 60th – as their number later became – operated in front and on the flanks of the infantry columns, from where they could bring rapid fire to bear on the enemy’s closely packed formations. They provided mounted infantry in the late-nineteenth-century wars in Egypt and during the South African War, 1899–1902. The 60th attracted officers of individuality and original thought, while its system of operations developed empathy and speed of reaction with close, confident relationships between all ranks. Its record for producing generals became formidable, making it widely – if sometimes grudgingly – respected.

Bramall did his basic training in Fulford Barracks, York, and was then taught to drive trucks, ride a motorcycle and operate radios with 148 Training Brigade in Wrotham, Kent. After return to the Officer Cadet Training Unit in York, he was commissioned into the 60th Rifles in May 1943 and joined the 10th Motor Training Battalion at Strensall, north of York, where new officers and soldiers were taught the tactics of a motor battalion. A fellow subaltern serving with him then and later in Normandy, Robin Lewin, recalls that while most of the young officers took any opportunity to go to London for the weekend, Bramall had little interest in night life.

It is a measure of the potential he had already shown that he was made the commander of the demonstration platoon. His company commander allowed him almost complete autonomy to teach all he had so far learned, often using his platoon as ‘enemy’ on battalion exercises. Bramall’s interest in minor tactics was given full leash, permitting him to set the standards that the trainees had to achieve and subsequently maintain in action. For the second half of the year he was with the 10th Battalion, he was given charge of the potential officers’ platoon. A system had developed since he had enlisted as a rifleman whereby those identified as potential officers were trained together. Many of these young men later served with him in action, having acquired much from his professional skill and, in the form of audacious field-firing exercises, something akin to a baptism of fire.

This period involved him in a traumatic experience, an incident that subaltern officers dread – a casualty on the grenade range, in this case a doubly fatal one. While simple enough, the technique of preparing and throwing a Number 36 grenade has an unnerving effect on the military novice. The principal danger is that the thrower, having pulled out the pin holding the firing lever in place, drops the grenade, releasing the lever. The fuse will then start burning and, unless they get out of the throwing bay in five seconds, both thrower and the supervising officer will be blown to pieces.

There is another risk when the grenade is thrown. Fragmentation ridges in the surface of the grenade, like that of a pineapple, tempt the thrower to apply a spin. Rather than a clean lob to the front, this almost invariably results in a shallow trajectory to one side. This is probably what happened when Bramall was supervising. The grenade went wide to the right, over the top of the adjacent throwing bay, rolled along the roof of the waiting bay and fell through a gap onto the soldiers below. Two men were killed outright and two others seriously wounded. The inquiry exonerated Bramall, finding fault with the siting and construction of the ‘waiting bay’, but dealing with the dead and wounded on the spot gave him experience of the sudden and violent death he would later encounter in Normandy.

In May 1944, he joined 2nd/60th at Worthing. This was a regular battalion, experienced and hardened by Western Desert battles and the Italian campaign, from which it had been withdrawn with the rest of 4th Armoured Brigade to prepare for the invasion of Normandy. Veterans were readily identifiable by the 60th’s red ‘cherries’ on their berets being bleached almost white by the sun. Reinforcement, re-equipping and reorganisation were essential before D-Day, so he found himself with a mixture of veterans and newly trained men in ‘A’ Company, commanded by Major Billy Morris, under the overall command of Lieutenant-Colonel Bill Heathcoat Amory, who had led the battalion since Alamein.

Battalions of the 60th Rifles and the Rifle Brigade were responsible for close support in action and protection at night of the tank regiments of the armoured brigades. Close support demanded manoeuvrability and speed comparable to those of the armoured regiments, including ability to think at the pace of the armoured battle, receive orders on the move and deploy swiftly off the line of advance to close with the enemy. Protection from enemy fire was far below the level provided for tank crews, at least until ‘Kangaroos’ – Sherman tanks stripped of their turrets – appeared in the final months of the war.

Motor battalions, as these units were known, had earlier been mounted in tracked, thinly armoured Bren gun carriers and wheeled 15-cwt trucks. By 1944, they were receiving the robust and more strongly armoured United States ‘International’ half-tracks. Scout cars and Willys jeeps were used for command and communications, while the Bren carriers were retained to carry mortars and medium machine-guns. Each battalion had three motor companies, one to support each armoured regiment in the brigade, and a support company with 3-inch mortars, medium machine-guns and 6-pounder anti-tank guns. Each motor company also had a ‘scout’ or reconnaissance platoon mounted in Bren gun carriers. Although a motor battalion’s dismounted strength was barely more than half that of a marching battalion, its vehicles and longer-range radios were valuable observation and reporting assets when it was required to hold ground.

Tactical headquarters and ‘A’ Company of 2nd/60th went ashore on ‘Juno’ beach with the leading elements of 4th Armoured Brigade on the evening of D+ 1 (7 June). Congestion on the beach was exacerbated by a German air raid, a rare event because of Allied air superiority, but ‘A’ Company was able to leaguer up for the night in an orchard clear of the beach. The following morning, 8 June, the company went into action. The 4th Armoured Brigade had been allocated a counter-penetration role between 3rd (British) and 3rd (Canadian) Divisions on their left and right respectively. This boundary proved to be the same as that between the 12th SS Panzer and 21st Panzer Divisions to the south. Almost immediately, the brigade had to prepare itself to repel an anticipated counter-attack by 12th SS Panzer Division in the area of the Villons-les-Buissons, a village on the western flank of the 3rd (British) Division’s salient overlooking a secondary road running in from the coast towards Caen. The attack came in with great force on the Canadians at Buron, less than three-quarters of a mile to the south-east, providing a useful check of 4th Armoured Brigade’s battle readiness and ability to call down air and artillery support.

The 3rd (British) Division had orders to capture the key communications centre of Caen before last light on D-Day. But, while the first two brigades reached their objectives without serious delay, fanatically held German positions in depth delayed the advance. Now the Allied strategy had to be confined, for the time being, to drawing the German armoured formations, which were fast arriving to join the battle, onto the British divisions holding the eastern end of the beachhead and hold them there while wearing them down with artillery fire and air attack. This was to allow the American 1st Army to break out in the west, against weaker opposition, seal off the Brittany peninsula and outflank the enemy’s main force.

By 9 June, 4th Armoured Brigade was ashore complete. ‘A’ Company 2nd/60th, with Bramall in command of a motor platoon, was affiliated to the 3rd City of London Yeomanry (3 CLY) equipped with Sherman tanks. Speaking of events afterwards, he recalled the intense excitement of the landing and move inland, only to be followed by a sense of anti-climax. As the 2nd Army’s initial aim had to be changed, 4th Armoured Brigade’s counter-penetration task left its motor battalion with little to do beyond guarding the tanks and mopping up enemy stay-behind parties, of which there were quite a number.

Operation ‘Epsom’, beginning on 21 June, was Bramall’s first major action, with 4th Armoured Brigade providing left flank protection for 15th Scottish Division’s move forward to seize crossings over the River Odon and get onto the high ground south-west of Caen. For the 2nd/60th this was a dramatic introduction to the awesome effect of Allied air power and artillery, naval and flat trajectory tank gunfire, while the enemy 240-mm guns, firing shells with a lethality area the size of a football pitch, and multi-barrelled mortar bombs were dealing death and destruction from the opposite direction. As Bramall watched two riflemen cross a field behind the forward slit trenches, a 240-mm shell landed some way from them; when he looked up, one had been decapitated and the other blown to pieces.

Caen remained in German hands until 9 July and on the evening of the 7th, 2nd/60th were overlooking the town from the edge of Carpiquet airfield. The range of their radios made them well placed to observe and report on events. First came the 450 four-engine bomber raid on Caen, preliminary to the final ground assault. The need for this massive air attack using high-explosive bombs rather than incendiaries has long been questioned, as it not only destroyed most of the town but congested the streets with huge blocks of masonry, seriously impeding the forward movement of Allied troops. It also led to the deaths of many hundreds of French civilians.

Several days later, 4th Armoured Brigade was ordered to cross the Odon and pass through 43rd Infantry Division, which was to have another shot at taking the high ground south of the river, then advance into the more open country beyond with the optimistic idea of seizing a crossing over the next river, the Orne (see Map 1). Intense enemy artillery fire and the abrupt appearance of Tiger tanks, which outgunned any tank the 2nd Army had in the field, brought 43rd Division’s attacks to a halt short of the high ground around point 112 and the fortified village of Maltot. The 2nd/60th waited their moment just to the north of Maltot throughout the afternoon and the early evening until they suddenly saw men of 43rd Division streaming back towards them.

Map 1. Operation Epsom, June 1944.

As ‘A’ Company’s orders group watched this alarming scene from the protection afforded by a reverse slope, a group of 88-mm flat trajectory guns opened fire from a flank. The bombardment was prolonged, with shells striking the ground around them. ‘A’ Company’s headquarters half-track received a direct hit, which killed Major Billy Morris, one of the subalterns, the company sergeant-major and all the drivers and signallers. Of the orders group members present, only Bramall survived.

Believing himself unharmed, he began to crawl from under the half-track where he and others had taken cover and saw alongside him the body of Lieutenant Bertie Jackson, an experienced platoon commander, scorched black by the blast of the 88-mm shell. On getting up, he felt a burning sensation down his side. Thinking himself on fire, he rolled on the ground to put out the flames, only to realise the sense of burning was in fact a wound in his side. At that moment, he was joined by the commander of the scout platoon, who had been on a reconnaissance, and, together, they were able to direct the remaining company vehicles into a nearby sunken lane to give protection from the direct fire of the enemy’s 88mm guns.

His wound was sufficiently serious to require his evacuation from the beachhead by hospital ship and special train from Newhaven to a hospital in Edinburgh. He was discharged a month later and joined the reinforcement chain for the return of recovered wounded to their units in France. En route, he met Major Roly Gibbs, who had been commanding ‘C’ Company and been wounded on the same day. He had also recovered and, through a blend of guile and forceful personality, the pair were able to accelerate their way through the reinforcement and returned wounded process so as to rejoin their battalion at the end of the battle to close the Falaise Gap in mid-August. Their wounds had kept them out of battle for only five weeks.

Then only twenty-three, Gibbs had won the Military Cross in the Western Desert and seen a lot of action in Italy. A fellow Old Etonian, he and Bramall struck up a firm friendship and thirty years later Bramall succeeded Gibbs as head of the Army. Meanwhile command of 4th Armoured Brigade had changed after Brigadier John Currie was killed at the start of the Epsom battle. Brigadier Michael Carver, promoted from command of 1st Royal Tank Regiment serving in 22nd Armoured Brigade, took over. He was twenty-nine and had made a name for himself as an operational staff officer with 7th Armoured Division in the desert and in command of 1st RTR in Italy.