Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Origin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

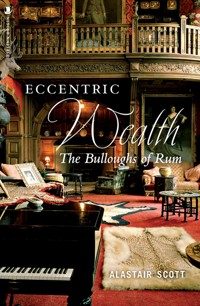

In Eccentric Wealth, Alastair Scott traces the life of Lancashire industrialist Sir George Bullough in this absorbing biography which explores his family's connection with the Hebridean island of Rum, particularly the building of Kinloch Castle, the most intact preserve of Edwardian highliving to be found in Britain. Based on new information, the book offers a fascinating insight into the life and times of one of the great eccentrics of his age, including the Bullough myths and scandals which continue to make extraordinary reading more than a hundred years later.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 431

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ECCENTRIC WEALTH

THE BULLOUGHS OF RUM

Also by Alastair Scott

Non-fiction

Scot Free: A Journey from the Arctic to New Mexico

A Scot Goes South: A Journey from Mexico to Ayers Rock

A Scot Returns: A Journey from Bali to Skye

Tracks across Alaska: A Dog Sled Journey

Native Stranger: A Journey in Familiar and Foreign Scotland

Top Ten Scotland

Salt and Emerald: A Hesitant Solo Voyage Round Ireland

Fiction

Stuffed Lives

Eccentric Wealth

The Bulloughs of Rum

Alastair Scott

This ebook edition published in 2011 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2011 by Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © Alastair Scott 2011

The moral right of Alastair Scott to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ebook ISBN: 978-0-85790-052-4

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

To Catherine Duckworth and Thomas Krebs

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

Map of Rum

1 Myths

2 Weft Fork and Slasher – James Bullough

3 Sin, Shame and a Prodigious Talent

4 Stormy Magnificence and Rude Mountains

5 George Comes of Age

6 When My Bones Are Laid to Rest

7 Illicit Affair and Escape

8 The World Tour, 1892–1895

Ceylon, India

Burma

Australia

South Africa

Madeira, New Zealand

The Orient, Pacific, and United States

9 Rhouma

10 Suitable for a Princess

11 ‘Water Cart Passed Over Head’

12 A Dream in Stone, Glass and Gadgets

13 Sexuality and Parties

14 Gomma and the Half-Tarpon

15 The Golden Age

16 Bare Feet and Tackety Boots

17 Poppies and Turf – The War Years

18 Rum Revisited – The Post-War Era

19 Deer, Fish and Fowl – Notes from the Records

20 A Selection from the Castle’s Correspondence

21 Death at Château de Courcet

22 The Forbidden Island

23 On Trust, in Trust

24 Loose Ends

Appendix A: Family Tree (Part of)

Appendix B: Summary of the Lives and Relationships of Other Bullough Family Members

Appendix C: Rum and Bullough Timeline

Index

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

James Bullough, founder of Howard & Bullough.

Early newspaper illustration of James Bullough and one of his looms

Howard & Bullough’s Globe Works, Accrington

John Bullough and his first wife, Bertha Schmidlin

The Rabbeth spindle

George aged 16, sitting for a school portrait

George and Robb Mitchell, Amber, India, January 1893

Crucified dacoits, Burma

Public execution, China

Man with a headcomb in Ceylon

A girl on a lily leaf in Java

Bamboo in Peradeniya, Ceylon

Tokyo’s infamous Nectarine No. 9 brothel

George’s half-brother, Ian

George’s full or half-brother Edward

Rhouma as a hospital ship

Rhouma II

Kinloch Castle c. 1910

One of Kinloch Castle’s Spode WCs

One of the revolutionary new showers at Kinloch Castle

A cartoon depicting George

An island guest posing by his kill

Sir George in his Rhum tartan

Monica Charrington (née Ducarel), who married Sir George in 1903

Monica posing nude

Monica’s sitting room in Kinloch Castle

Kinloch Castle today from the north

Sir George on the cover of Sport Pictures

A childhood drawing on The Public School Latin Primer

Sir George in later life

The majestic beauty of Harris, west Rum

The final resting place of John, Sir George and Lady Monica Bullough

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I first went to Rum in 1972 with a school camping expedition. The experience made a profound impression on me and Rum has lured me back many times since. Over these decades the spelling of the island’s name has changed from ‘Rhum’ to ‘Rum’ – the details are given in the narrative – but to avoid confusion I should point out here that both refer to the same place.

The more I learned about Rum the more incredulous I became that no one had written a biography of Sir George Bullough or troubled to investigate the intoxicating rumours of extravagance. My priority with this book has been to create a factual, and above all readable, account and to this end I have given reference sources for major or controversial quotes, but not for the minutiae. To keep footnotes to a minimum I have included an Appendix on some of the Bullough family who played a part on the fringes of Sir George’s life, and added a timeline so that the chronology of events can be followed with greater ease and clarity.

Sir George died in 1939, Lady Bullough in 1967 and their daughter Hermione (Countess of Durham) in 1992. There will be many people who knew them personally, and more who heard about them indirectly through others. I would be delighted to hear from anyone who would like to share memories or recall incidents involving them. No biography can ever be considered ‘complete’ and many gaps remain in this one, despite three years of research. This book is my best attempt using the archive material available. If any of my facts or theories are wrong, I welcome the opportunity of correcting them.

I can be contacted through my website: www.alastair-scott.com.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

George Randall and Ewan Macdonald founded the Kinloch Castle Friends Association (KCFA) in 1996. In the pages that follow I pay tribute to the enormous impact this organisation has had in bringing the plight and importance of the castle to public attention. I hope this book inspires many more to lend support. Details can be found on www.kinlochcastlefriendsassociation.org

Catherine Duckworth is the font of knowledge on all aspects of the Bulloughs in Accrington, and much more besides. Without the information she provided and ideas she inspired, this would be a much leaner volume. Her support and proofreading were invaluable and to her I owe my biggest debt.

Thomas Krebs has left a well-trodden trail between Rum and his native Switzerland, where he alone has uncovered the Schmidlin strand of this story and eagerly passed on his findings. Thanks also, Thomas, for guiding me around the Giessbach.

George Randall is a leading authority on the Bullough family and castle. I am grateful to him for sharing some of his research in the KCFA Newsletters. At the outset these informed much of my own understanding and provided me with springboards into unexplored pools.

Other KCFA members who assisted were Douglas King (for the post-Bullough period), Mary Wardle (the Uddingston connection), John Bullough, Graham Bullough and Julian Mackenzie-Charrington.

Thanks to Scottish Natural Heritage – in particular, David Frew, who could not have been more obliging in allowing me access to the castle archives, and Tom Cane for readily answering emails choked with questions.

To Rita Boswell (Harrow School Archives), Gill Parker (recollections of Percy Hill’s family), Josephine Pemberton (red deer), Patrick (the Fujiya Hotel in Japan), the staff of the ObanTimes, Lancashire Record Office and many libraries including Accrington, Skye mobile, Highland HQ, Perth, Fort William and the National Library of Scotland – also thanks.

Permission to use extracts from published works is gratefully acknowledged for the following:

p. 17, Pen and Sword Books for Aspects of Accrington, Discovering Local History, edited by Susan Halstead and Catherine Duckworth, Wharncliffe Books, 2000.

pp. 30, 45, 156, 172 and John Love, Rum: A Landscape without Figures, Birlinn Ltd, 2001.

p. 54, Debrett’s Peerage and Baronetage

p. 135, Garry Otton (author) and John Hein (editor) have both given permission for this passage to be quoted from Scotsgay Magazine, Issue 53A, September 2003.

p. 146, Country Life, 9 August 1984, from an article by Clive Aslet.

p. 153, The Scots Magazine, December 1978, article by Archie Cameron.

p. 157, Derek Cooper, Hebridean Connection, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1977, page 85.

pp. 154, 163–171, 179, 186, 214, 224, Archie Cameron, Bare Feet and Tackety Boots, Luath Press Ltd, 1988.

p. 211, Alastair Dunnett, The Canoe Boys, In Pinn, 2007. First published under the title Quest by Canoe, 1950.

Despite every effort I have been unable to contact the following copyright-holders:

p. 158, Bridget Paterson, Kinloch Castle Friends Association newsletter no. 4, April 1998.

p. 210, Donald Cameron, While the Wild Geese Fly: Tales of a Highland Farmer and Auctioneer, privately published by Glen Nevis.

p. 221, Alasdair Alpin MacGregor, An Island Here and There, Kingsmead Press, Bath, 1972.

p. 221, Scotland’s Magazine, 1959, from an article by Sir John Betjeman.

Sport Pictures for the ‘Golden Ascot’ photograph

Hi-Arts awarded me a Scottish Arts Council research grant which allowed me to penetrate deeper and further afield than I ever would have done at my own expense, and I’m grateful for the considerable bounty of fact and detail added to an important facet of social history.

Final thanks to Birlinn, namely: Hugh Andrew, for believing in this book and Tom Johnstone, for adding fluency to my prose.

Best wishes and prosperity to the Rum Community. www.isleofrum.com.

1

Myths

With a theme of rags to riches, this story spans three generations of a Lancashire family, the Bulloughs. There is grandfather James, the founder, father John, the augmenter and – much the most mysterious and fascinating – son George, the spender. He takes high living to a new extreme. Divorce, scandal and rumour – always rumour – attach themselves to the family name and a cupboard door falls open to reveal the skeleton of a lost son. The Great War intervenes and effectively kills the Golden Age of partying. But what a party it was! Its legacy endures. Around George and his beguiling life of excess a legend is born.

Like most legends it has become a glorified concoction of fact and fabrication. That the life and legacies of George Bullough have so readily transcended logic and entered the realm of myth is not surprising. He was an intensely private man and left few written records of his thoughts, feelings or deeds. More than this, though, the family’s history appears to have been concealed with a determination that is both odd and suspicious. Were it not for the newspaper reports that have provided most of the details in this book, the family’s self-effacement would have succeeded, and the story remained irretrievably enmired in hearsay. George’s nearest living descendant, a single grandson, declines all contact with researchers. The few other close relatives I’ve managed to contact have evaporated the moment my subject is mentioned. Where voids exist in the foundation of a visibly ostentatious lifestyle, imaginations run riot. The Bulloughs were fertile ground for gossip.

One possible explanation for their secrecy may be gleaned from a reflection on the times. Although the story in its Scottish context took place long after the most brutal and repellent instances of landlords evicting their tenants for motives of profit, one member of the family conducted his own small-scale clearance. The family’s wealth came through the effects of the industrial revolution which is associated with abuses and exploitation. There may have been retrospective embarrassment over these involvements, or others of an even more sensational kind which will be referred to later.

Briefly, here is the popular version of the story in its most lurid, scurrilous and least trustworthy form.

George Bullough was fourteen years old in 1884 when his father, John, married for the second time. By then John was a man of exceptional fortune, a manufacturer of cotton-processing machinery in Accrington, Lancashire. John’s father had started the business and transformed himself from a mill urchin into a successful inventor and entrepreneur. John exceeded his father’s accomplishments in both areas and, in 1884, was rich enough to buy a large sporting estate in Perthshire. This was the venue for his marriage to a Stornoway girl, Alexandra; he was forty-six, she nineteen. George attended the wedding, completed his schooling at Harrow and became a cavalry officer in the Guards. He was tall, handsome and athletic. His step-mother was pretty, vivacious and only a few years older. Before long they were caught in bed together. Thunderously displeased, John banished his errant son on a world cruise in the family yacht. To console himself, John added a new playground to his portfolio, the Hebridean island of Rum.

George’s voyage was planned to last five years, and as an incentive not to curtail it, he was given an unlimited spending allowance. Rhouma was no ordinary vessel but a luxurious steam yacht 221 feet in length. Cricket matches were held on her deck. Her crew of forty included an orchestra and personal photographer. Along with a few friends George set out on a route determined by the whim of the moment: South Africa, India, China, Japan, Australia, America and various places in between. The photographs he returned with bear witness to a remarkable journey: there he is on an elephant in Rajasthan, here, apparently, standing among a carnage of heads and decapitated torsos after a mass execution during the Boxer Rebellion; there, perhaps, posing in the up-ended roots of a giant redwood, and here, surely, leering from behind his photographer’s shoulder at sixteen bare-breasted wives of African Chief Usibeppo.

He met the Tsar of Russia and the Emperor of Japan. At an auction in Kyoto he outbid Emperor Meiji for a life-sized ivory eagle. The emperor wanted it to make a matching pair for his collection and, having failed, he subsequently lost interest in his lone eagle and sent it to the Tsar of Russia as a wedding present. A magnanimous gesture, for his country had just defeated Russia in war; the peace treaty was signed on board Rhouma, and for accommodating this George was presented with a bronze monkey-eating eagle weighing many tons. These and many other souvenirs were loaded onto Rhouma and taken back to Britain, somewhat sooner than planned, as news reached George that his father had died. The date of his death was 25 February 1891, and the celebration of his twenty-first birthday, three days later, was a suitably muted affair. After the funeral and the revelation of his inheritance, he discovered just how rich he had now become.

George’s annual income was suddenly in excess of £300,000. Comparative values are hard to compute, but in terms of purchasing power this equates to many million pounds today. He wasted no time in putting it to use and commissioned the building of a castle on Rum. No expense was spared. Disliking the colour of local sandstone, he imported the rich red of Arran’s deposits. Puffers by the hundred landed their cargoes on the rocky beach at Loch Scresort, including 250,000 tons of Ayrshire topsoil for the Japanese gardens and golf course. Three hundred workmen and forty master carpenters laboured for three years to create the splendour of Kinloch Castle. It boasted every innovation of the times. Glasgow was the first place in Scotland to install electricity, Kinloch Castle was the second. Windows incorporated a unique system of double-glazing, the internal telephone system was found in few other stately homes anywhere in Britain and revolutionary showers produced 360 degrees of jets with variable functions and phases. Outside, fourteen gardeners transformed the grounds. In acres of glasshouses a tropical paradise was replicated with palm trees and free-flying humming-birds. They flitted among crops of peaches, nectarines, figs and grapes: below them, in separate ponds, turtles and alligators basked apathetically prior to becoming soup for those extra special occasions. So it is said, so it is said.

While the castle was being built, the Boer War started and George offered to fit out Rhouma as a hospital ship and take her to Cape Town. The offer was accepted and for the year that such facilities were needed, many wounded soldiers experienced a level of comfort that was probably never again matched in their lives. For this service George received a knighthood. That at least is one explanation. The other is more popular and irresistibly salacious.

George had met a society belle called Monica Charrington. Not one to let a decade of unhappy marriage cramp her style, Monica was reputed to have had a string of affairs among London’s rich and famous, and been a mistress of Edward VII. The liaison threatened to breach what little respectability the future king retained, and to avert a public scandal, George stepped in to take Monica off His Highness’s hands. It was George who was cited as co-respondent in Monica’s divorce rather than the Prince of Wales, and for this he earned royal favour and a knighthood. Sir George married Monica at Kinloch Castle in 1903.

The parties now began in earnest. Sir George and Lady Bullough preferred to enjoy separate lives when visiting Rum, each with their own choice of guests and lovers. Monica had a nude portrait painted and hung outside her room. Erotic French prints leered down from the walls of her drawing room and she had the castle refashioned to suit her tastes. George filled his library with pornography. Gaiety Girls and prostitutes were transported by special trains to Oban and thence by the versatile Rhouma to the shores of Rum. On the lid of the Steinway piano in the Great Hall you can see the scratches caused by the high-heels of one who was lifted up on it to dance. On several occasions a secret attendee was Edward VII. Not content with these affairs – so the tittle-tattle goes – George indulged a lust for all-male parties too. When the castle was being built he paid the workers extra if they wore kilts; the better to admire their physiques. When the castle was vacated in 1957 a sadomasochism cage was found in the cellar. Or so they say.

Deer and trout were imported to improve the quality of trophies, and the Bulloughs and their guests spent the days ‘sporting’. French chefs cooked their meals and they were summoned to eat by the Orchestrion, a mechanical marvel that simulated a forty-piece orchestra and was played like a jukebox. Only six were ever made, and this one, built for Queen Victoria who died before it could be delivered, cost him one-third of his annual income. A real orchestra played in an upper recess in the ballroom, screened by a thick curtain from the antics below. Drinks were served through a double-doored hatch that excluded any glimpse of the life beyond. The dancing, and whatever else ocurred, took place below a ceiling studded with little lights to emulate a galaxy of stars. Squads of roadmen were employed to maintain the tracks over which George and his friends raced Albions at Le Mans speeds to the other side of the island. Additional staff were needed to care for his pack of twenty-four hounds. The pack lived in heated kennels, whereas the living quarters of the housestaff were unheated. Thus the stories go.

These then were the heydays of castle life. Then came the war. The decline set in. The Bulloughs’ visits became less frequent, less prolonged. The glasshouses were abandoned, the hummingbirds and turtles died, the alligators were shot. Rhouma was sold and replaced by a slightly smaller superyacht.

Kinloch Castle had never been anything other than a holiday home, used for a few weeks each year. Despite reduced expenditure on Rum the Bulloughs’ lifestyle after the war continued much as before. They returned to Rum each autumn for the stalking season. The veil of secrecy concealing their private lives there was preserved and Rum assumed the reputation of the ‘Forbidden Island’, where outsiders were denied a landfall. The Bulloughs spent more time circulating round their other homes in London, Worcestershire and their specially commissioned house at Newmarket, where George indulged his passion for owning and breeding racehorses. He seemed to attract success. His horses won the Grand National and the Ascot Gold Cup. His dogs took prizes at Crufts. He was Master of the Ledbury Hunt. Sir George and Lady Monica continued to travel. The font of their income never dried. The parties they began continued, and continue. Their superyacht still sails the seas. Their castle is preserved. Their footwear still rests by their beds. They were never allowed to die. Large in life, they just kept growing larger in the mind.

* * *

For decades visitors to Rum have been regaled with the more sensational accounts of the castle and the Bulloughs’ lives. When indolent writers feed off the regurgitated output of their predecessors, then inevitably the same half-truths and inversions are repeated and exaggerated until they emerge with the apparent bloodline of fact. Few seem to have questioned, for example, how George Bullough heard about his father’s death in 1891, broke off a world tour in Salt Lake City (where the photograph albums abruptly end) and managed to arrive back in Accrington in time for his father’s funeral a week later. Nor how he managed to sail round the world in Rhouma and return with photographs dated 1894, when he didn’t purchase Rhouma until the end of 1895. His travels certainly took place and Rhouma did indeed make extensive voyages, but here, as in many other areas of a saga rife with conjecture, truths have been wrenched out of context and chronology and manipulated into a different tale.

This book’s intention is to set the record straight. Many of the most extreme elements are true. Others are plausible but unsubstantiated. Some are pure fabrication. The George Bullough story is lustrous enough based on the known facts.

2

Weft Fork and Slasher – James Bullough

Accrington (a ‘town surrounded by oaks’ in Saxon times) all but fills a long, abrupt valley high in the Lancashire dales. The oaks have long gone, but the odd copse of trees breaks the horizon where a fringe of farms and fields make a last stand against the upthrust of houses. These form an impressive symmetry of parallel terraces running steeply down to the town centre. Once a dense amphitheatre of smokestacks, the town’s notable landmarks now are an abundance of churches, the finest market hall in the county and the railway line which straddles the centre on a viaduct. The air of decline is heavy. The heart is a shopping centre, the pulse weak. Lancashire wit and friendliness remain irrepressible, but the sense of abandonment is unmistakable, as if all the locals have really got left is their football club. Accrington Stanley’s fame rests on being very old, unwilling to succumb to destitution and failing to recognise when it should be defeated by superior teams. ‘Th’ Owd Reds’ seem to bear a double burden of the community’s pride and hopes.

For its survival in the age of emerging industrialization, Accrington was fortunate in its geology and geography. The Burnley coalfield extended to the town’s limits and provided both fuel and mining employment. The surrounding hills were a source of gritstone for building and mudstone for the ‘Accrington brick’ that brought initial and enduring commercial fame. A reliably wet climate ensured the river Hyndburn flowed strongly through the town’s centre, and this was harnessed for both power and washing in the new processes of cotton manufacture. The Leeds-Liverpool canal looped the outskirts of the town and railways brought connections east, west and, crucially, south to Manchester. When technology led to the building of factories, then inevitably Accrington was poised to take full advantage of its commanding position. There was abundant labour to move into town from the rural cottage industry of handloom weavers, now becoming redundant, and enough creative vigour in the community for Accrington to spawn its own inventors and radically alter the wider world. What was to distinguish this town from a plethora of others which enjoyed similar advantages and growth was the breadth and diversity of its industrial base. The cotton industry dominated, but around it was formed a solid bastion of related and unrelated manufacturers.

At school certain names and dates were drilled into the minds of pupils in connection with the development of the weaving industry. In my case, little of what we learned remains except a vague recollection of Hargreaves and something wonderful called a spinning-jenny. In researching this book I have had to address that deficit.

In fact it was an earlier inventor, a clockmaker called John Kay, who is credited with the first revolutionary idea. In 1733 Kay dreamed up the flying shuttle, which exponentially increased weaving speed and enabled wider bolts of cloth to be woven. In 1764 came the spinning-jenny, supposedly invented by Lancastrian James Hargreaves. The tale persists that when his daughter, Jenny (coincidentally also an old name for an engine), accidentally knocked over his spinning wheel it gave him the idea for a way of activating eight, later eighty, spindles from one turning wheel.

The reality is somewhat different; Hargreaves was given, and later claimed as his own, the preliminary plan for the spinning-jenny by a man called Thomas Highs, a brilliant inventor who never had the funds or acumen to protect his ideas. The spinning-jenny’s flaw was that the threads it produced were coarse and weak and could only be used for the weft (the threads woven at right angles to the length of the warp). This problem was also solved by the unfortunate Highs. He discovered that sets of paired rollers turning at different speeds would produce the much-desired, fine, strong thread. The problem was how to power the machine. The ‘Frame’, as it was called, was too heavy to be turned by hand. Highs adapted it to the principles of the millwheel and harnessed the power of water. His Water Frame was adopted by wigmaker Richard Arkwright, who joined forces with John Kay. Kay had been all but bankrupted by litigation fees when trying to enforce his patents for the flying shuttle. Together they turned the Water Frame into a commercial success and are credited with inventing it.

So, two inventions revolutionised spinning and one weaving. The other famous figure in cotton manufacture is Edmund Cartwright, a clergyman, who is recognised as the progenitor of the first power loom, despite never having made a viable model. His best effort of 1786 provided the breakthrough and others redesigned it into a successful machine.

Nowhere in the history of weaving during the industrial revolution do James or John Bullough feature prominently. Yet it is arguable that their inventions and enterprise over the years contributed as much to the advances in output and efficiency in the cotton industry as any of their celebrated predecessors. What has been recognised is that its local sources of both genius and prototype machinery allowed Accrington to lead the world for decades, and without them, the Lancashire cotton industry would have died in its infancy. What differentiates the Bulloughs’ inventions from those of Kay, Hargreaves, Arkwright and Cartwright is that theirs were not revolutionary changes but incremental improvements of existing processes. Radical they certainly were, and they numbered many dozens, and they carried technology to new heights over a long period.

In a thoroughly unreliable family tree the earliest mention of the Bullough origins in Lancashire dates back to c.1200, with a ‘Stephen Bulhalgh’ resident in Kirkdale. The family surname metamorphosed through various forms, some Norman – de Bulhalgh, Bulhaigh, Bulhaighe and Bulowghe – to the first recorded ‘Bullough’, born around 1580 at Little Hulton in the Parish of Deane. This was close to Bolton, some fifteen miles south of Accrington. Over the next seven generations the family migrated no further than five miles away and, in 1799, the future co-founder of the world-dominating Globe Works was born in the hamlet of Deane. He was named after his father.

His parents, James and Anne Bullough, were a typical working-class couple of impecunious means. Life for the masses was still a crude struggle for existence. Candles and oil lamps provided light. The penny post had yet to appear, universal education did not exist and the rush to steam power was decades away. James senior was a handloom worker in what was still predominantly a cottage industry. Powerlooms had been invented, but their use was not widespread, although several small spinning factories using water power had started up in nearby cities.

The young James was seven when he was apprenticed to a handloom weaver in nearby Westhoughton. Despite his lack of schooling he possessed the natural gifts of an inventor’s eye and an engineer’s mind. While progressing from hand-weaving through a series of mill jobs he noticed how much time and material was lost whenever the weft broke. Using some of his sister’s plaited hair and linking it to a bell, he adapted his loom so it sounded a warning each time the weft tension slackened. The Self-Acting Temple, as it became known, was his first major success. Although the financial rewards were small, his ability was recognised and he soon became an ‘overlooker’ (foreman) at mills in Bolton and Bury. In 1824 he married Martha Smith.1 The following year he became manager of a small factory, where he introduced his latest improved hand-loom, the Dandy Loom.

James Bullough’s innovations did not meet with universal approval. This was an era of inflammatory discontent as traditional weavers saw their livelihoods threatened by technology. Aged thirteen, James Bullough may have witnessed the notorious Luddite riots which swept Lancashire and Yorkshire in 1812. Now seen as a marked man, accelerating the pace of change, his position was precarious, but his drive for new inventions never wavered. His biggest breakthrough came in 1841, with the joint patenting of the Roller Temple and Weft Fork for powerlooms. The effect was dramatic and produced the famous Lancashire loom which, with subsequent modifications, was to remain the workhorse of the weaving industry for over a century. The effect was equally marked in the public outrage it caused. Employers were threatened with violence and walkouts by their workers if they showed any interest in the ‘professed improvement of the loom, introduced at the Brookhouse Mills in Blackburn’.

Another depression had set in, and such was the hostility to innovation in the streets that, for at least the second time in his life, James had to flee Blackburn for his personal safety. The troubles continued and reached a climax in August 1842, when 700 Special Constables failed to prevent crowds storming one mill after another, destroying boiler plugs and rendering the weaving machines useless. This incident entered history as the Plug-Drawing Riots. Bullough’s Brookhouse Mill was specifically targeted and another petition was brandished by protestors, denouncing the Lancashire loom for which ‘the patent was considered to be an evil in all its bearings’. Not that he knew it then, but this was the last major resistance the indomitable James Bullough had to face. Thereafter the populace was forced to move to the inevitable quickstep of change.

In 1845 James ended fifteen years at Brookhouse and moved on to other mill-owning partnerships in Oswaldtwistle, Water-side and then Baxenden. Now trading as James Bullough & Son, with two sons actively involved in the expanding business and a third, John, completing his education, James spent more time indulging his passion for invention. His list of patents had grown long, and included such mystifying names as the Weft-Stop Motion and the Loose Reed, but the admirable fortune they had amassed for him to date was rendered insignificant by the revenues of the next one, the Slasher.

The year was 1852, and the Slasher was a collaborative achievement with two employees2 whose names also appeared on the patent; James Bullough played fair in all his dealings. The Slasher was an advanced system of sizing and starching the warp, producing a three-fold increase in output over previous machines. It proved to be an instant success. Up to this point James had operated mills and introduced all the benefits of his ingenuity, but he had never owned a factory which produced the machines he designed. This was about to change through another stroke of luck in his charmed life.

In 1853 a 38-year-old engineer from Bury called John Howard started a loom-making enterprise with a little-known individual, James Bleakley. They chose Accrington for this modest venture, comprising four employees in a huddle of wooden huts. The wages bill for the first week totalled £5 17s 9d. For unknown reasons Bleakley soon pulled out, and left his partner without any working capital. Howard struggled on until 1856, when his failing business caught the eye of James Bullough. He saw the potential at once. The two men were a perfect match. Howard had the engineering skills, Bullough had the ideas and a very deep pocket. Soon Howard & Bullough, Globe Works, Accrington, manufacturers of looms, outgrew their huts and were launched into a continual process of expansion.

Despite the turbulence caused by his inventions, James Bullough was a popular man. All his life he worked hard, and it was not uncommon to find him toiling through the night in his office or workshop. Indeed it was said that he ‘slept on his looms’. As a child he had only ever worn wooden clogs, and in later life he never wore any other footwear, his only concession to respectability being a top hat, which made him a somewhat incongruous character. In his pockets during summer he habitually carried peas from his garden and handed them out to children as if they were sweets, and would often linger to join in a game of marbles. Despite his wealth he preferred the company of his colleagues and less privileged friends. Above all he was a quiet unassuming man who valued his privacy and avoided publicity – quite unlike his youngest son, John, who had been selected to succeed him.

James’s remarkable life ended on 31 July, 1868, at Ibrox Terrace, Govan. He was visiting his daughter who lived there. Dying on holiday came to be a perverse idiosyncrasy of many of the Bulloughs, but it was perhaps most unexpected in James’s case. He was rooted in his native Lancashire and had never travelled far afield, at least not in physical distance. In every other respect, his sixty-nine years had been an epic journey.

1 Most sources give her maiden name as Smith, but one as Millar.

2 David Whittaker and John Walmsley.

3

Sin, Shame and a Prodigious Talent

Written into the contract drawn up with John Howard was the provision that James’s youngest son, John, would join the management of the company when he came of age. Early in life John must have shown signs of unusual ability for his father to favour him over his older brothers. James once told a neighbour that he’d made provision in his will for his two eldest sons, Jim and Will (he left each of them a cotton mill), ‘but the Globe is for John. An’ if ee won’t make it do, then it won’t do’.

Clearly regarding his own lack of education as a drawback, James was determined to give his most promising son the best opportunities to study and learn. John was sent to Queenwood College in Hampshire, which was one of the first schools to specialise in teaching science and agriculture. It was an experimental institution founded by Robert Owen, the visionary humanist and philanthropist, most famous for creating the model community of New Lanark (1800–25). His philosophy must have made an impression on John, for it was to feature in his own style of business management.

From Queenwood he went to Glasgow University to study arts but did not graduate. Perhaps the future challenge of making the Globe Works ‘do’ was too absorbing, and rendered the completion of a degree in abstractions irrelevant. At face value arts was a strange subject for a natural engineer to take up, but less so when seen from the perspective of a family aspiring to belong to the upper echelons of society, where an appreciation of music and literature could not only be indulged but was rapidly becoming the essential fashion of empire.

John’s date of birth, and consequently his age at all landmarks in his life, is a source of confusion. The family tree, inscription on his sarcophagus, obituary notices and entry in his marriage register all conflict with one another. His Swiss marriage certificate gives the earliest birth-date of 14 November 1837, whereas the age engraved on his tomb computes his year of birth as 1839. Any discrepancy is not particularly important and 1837 is the date I have assumed to be correct. As his parents married in 1824 John was relatively late on the scene, yet four sisters were born after him.

Despite his low ranking in the male order, John joined Howard & Bullough and served his managerial apprentice at the top. His father retired in 1863 and a new deed of co-partnership was drawn up with the original founder, John Howard. When Howard died three years later, John Bullough found himself in sole charge of the Globe Works. He was twenty-nine years old.

The population of Accrington in 1801 had been 3,000. By 1868 it had increased to 20,000, and 500 of these now found employment at Howard & Bullough’s Globe Works. The annual wages bill was £8000. Within three years of his taking over as manager this had risen to £30,000, and by 1874 to almost £40,000. John Bullough was certainly making the Globe ‘do’. He was every bit as hard-working as his father, and his genius for invention equally luminous. Between 1866 and 1888 he filed no fewer than twenty-six patents.

His masterstroke, however, came from someone else’s invention, whose potential he was quick to recognise. In 1876 he crossed the Atlantic to attend the American Exhibition held in Philadelphia. Here he spotted the Rabbeth Spindle, a device whose special system of bearings allowed it to carry unbalanced loads and run at ‘unlimited speeds’, certainly in excess of 20,000 revolutions per minute, when conventional spindles seized at around 7000 rpm. The ‘ring’ spindles took less power, so one machine could drive more of them. The ramifications, Bullough realised, were enormous, even though it meant he had to persuade the industry to move from the standard ‘mule’ frame to a new ring frame.

F.J. Rabbeth, a skilled machinist at the Remington rifle armoury, was reluctant to part with the rights to his spindle and Bullough found him to be a shrewd negotiator. In the end Bullough won, and purchased the patent ‘for a considerable amount of money’. Along with the legalities the price included working models of the spindles and the necessary tools and machinery to copy them.1

If Rabbeth came away feeling he had done well, Bullough knew he had done better. As George Randall explained in Aspects of Accrington,

In 1878, the manufacture of the Rabbeth Ring Spindle commenced at the Globe Works and its success spurred a massive extension and reconstruction programme, including moulding shops and timber yards. New and larger engine houses, a dozen in all, were required to drive ever more machinery as production increased and the workforce grew to over 2,000. Within a few years, many millions had been produced for the home and world market, turning Globe Works into the truly global empire its name implies.2

The Rabbeth Spindle was to stand alone as the most important single development in the cotton industry for decades. John Bullough not only had turned a small family factory into the driving force behind world cotton production, but he had introduced a style of progressive management that was to endure long after his death. The scale of his ambition was matched by his ebullient personality.

His obituary revealed that ‘discipline was one of Mr Bullough’s cardinal principles and the Globe Works was no place for the lazy or indifferent workman’. Tough and uncompromising as he was in attitude and opinions, John was nevertheless not one to exploit his workers – at least when judged by the standards of the times. The Factories Act of 1833 was intended to protect children from excessive work regimes and decreed that:

1. No child under nine years of age should be employed.

2. Children between nine and thirteen years of age are not to work more than nine hours per day.

3. Children between thirteen and eighteen years of age are not to work more than twelve hours per day.

In reality many factories disregarded the Act, and there were insufficient inspectors to enforce it. Mines were excluded from its restrictions, and it was not uncommon for children as young as five to be found working fourteen-hour days underground. Not until 1840 did it become illegal to use boys as chimney sweeps. The Factories Act was enforced at the Globe Works, and in 1871 John Bullough became the first Accrington employer to extend the nine-hour working day to all employees. The six-day working week was thus reduced from the standard seventy-two hours to fifty-four.

For this voluntary adoption of what had become known as the ‘Nine Hours Movement’, he was presented with an ornate, coloured ‘Testimonial’ by his grateful workforce on 5 December 1871. It begins: ‘Dear Sir, IT is with feelings of deepest gratitude that we take this opportunity of expressing to you our heartfelt thanks for the very handsome manner in which you have given us, unsolicited, the boon of fifty-four hours working time to constitute a week’s work without reducing our wages . . .’

What a remarkable turn-around from the days when James Bullough had to flee his workforce for his ‘professed improvements’!3 While not in the league of Robert Owen, who transformed an industrial community with schools, wholesome food and free healthcare, John Bullough showed distinct philanthropic traits. He established Howard & Bullough’s Technical School – among the first of its kind for the development of employee skills – and the Accrington Mechanics Institution, was elected President of the Accrington and Church Industrial Cooperative Society and poured generous funds into the coffers of ailing churches. His vitality must have been extraordinary, because his sponsorship and presidencies extended from the Lancashire Football Association to local football and swimming clubs. One newspaper obituary later observed that he ‘was fond of sport and “somewhat aggressive”. Generous, and an excellent judge of character and ability in others. He was robust in health, “full of life”, courageous and determined. He could not suffer defeat in racing, boxing, wrestling or cricket.’

He kept a championship loft of racing pigeons, and was passionate about shooting, horse-racing, cock-fighting, boxing, dogs, music and unfortunately – as will be demonstrated later – writing poetry.

But his interests did not end there. Unlike most industrialists of the period who were Liberals, John was a fervent supporter of the Conservative and Unionist Party. He was a firm believer in capitalism pure and simple, and abhorred any act of government interference. He founded, and largely funded, the town’s first Conservative Club. He served as its chairman and was selected to stand for parliament, but in the end declined because of business commitments. Such was his esteem in the community that invitations to make speeches arrived frequently and were rarely refused. His addresses were widely reported by the press on such subjects as, ‘Why a working man should be a Conservative’ and ‘Licensed victuallers versus teetotalers.’ He was also a regular writer of Letters to the Editor, sounding off on a wide variety of issues. These give a penetrating insight into his character and prejudices.

Letter to the Accrington Gazette, on the subject of the Proposed Free Libraries

22 March 1887.

Sir,

As to a free library, whilst I admit the pleasing sound of the name and one eminently suited as a catchword to tickle the ears of all of us who are in the philanthropic fashion of the day, I don’t think the project can stand investigation. I believe some seventy per cent of the books which these readers take out of these libraries are novels. I’ve no particular objection to novel reading, except to the trashy sensational sort; but I hardly think the rate-payers are in any way called upon to supply novels to novel readers. The circulating libraries, for a very small annual subscription, enable anyone to obtain as much and more of this class of literature than is good for him or her. As to those who wish to read serious books – books requiring to be studied rather than read for solid instruction – few books will suffice for them; they can therefore buy them for themselves and they will think better of them when they have thus acquired them . . . Therefore you will see that I am no enthusiastic supporter of free libraries at the expense of the ratepayers.

I am, yours faithfully

John Bullough

Letter to the Accrington Gazette, ‘Lady County Councillors’

May 11, 1889.

If I know my own mind at all I speak out of respect for women and because of that respect I would save them if I could from mixing in the rough-and-tumble world of politics . . . Such work will impair their best feminine qualities. In measure as they ape man and approximate their natures to his in the same measure they will forfeit that claim to chivalrous treatment which is theirs so long as they remain women, and which it is men’s duty and pleasure to extend to them when in their legitimate sphere.

But do these fine ladies imagine that they can enter the rough and rude arena of politics and contend with men and not receive their share of hard blows? If so, they are sadly mistaken. If they don’t act as women they can’t be respected as women. When they themselves disclaim their weakness and enter the strife as men’s equals, there is no room for chivalry – they forfeit all claim to special consideration. For my part I hate strong-minded women. I think they are enemies of their sex. They are the products of, and the associates of, weak-minded men. In proportion to my hatred of them is my respect for woman in her true sphere exercising her legitimate influence. I don’t like to see my ideal destroyed and transformed into a repulsive creature ‘half-Margaret and half-Henry’.

Apart from haranguing editors, delivering orations, funding good causes, running a business empire, producing twenty-six inventions and indulging a myriad interests . . . he also had a family to consider.

On 11 February 1869, barely six months after his father’s death, John Bullough, then thirty-two, married German-born Bertha Schmidlin in her adopted Switzerland. Bertha was the daughter of Eduard Schmidlin, director of the famous Grandhotel Giessbach near Brienz.4 She was twenty-one and already widowed, her husband having died four months after their wedding. How John and Bertha met is not known, but it seems likely that Bertha had returned to work at her father’s hotel to rebuild her life, and John stayed there while on business or holiday. The marriage took place at the Reformed Church in Brienz, a pretty lakeside town set below towering mountains. Given the qualities John expressly admired in women, one can only imagine that Bertha knew her ‘legitimate sphere’ and was not strong-minded – in the beginning, at any rate.

After their honeymoon the couple returned to John’s then home, the Laund, in Accrington. The following year, on 28 February 1870, a son was born. He was christened George in Christ Church. A daughter followed two years later and was named Bertha after her mother. The Bullough family soon moved home to Oswaldtwistle, just outside Accrington, where they leased Rhyddings Hall. This stately home, set in its own park, had been built in 1845 by Robert Watson, a former partner of James Bullough and by then a wealthy mill-owning magnate. It was here that George, the central figure in the story that follows, and his sister Bertha spent their childhood.

Life for their mother, moving from a spectacular and cosmopolitan home in the Swiss mountains to industrialised Accrington, proved to be insufferable. She must have spent considerable periods alone, despite accompanying her husband on occasional business trips as far afield as America and Europe. How willingly she went is not known, for John turned out to be a violent bully from their very first night together. Their divorce proceedings, discussed later, list an appalling catalogue of his abuses. Bertha walked out in September 1879, and yet matrimonial relations appear to have continued until early summer that same year, for nine months after that a second son, Edward, was born.

Edward is one of the mysteries in the saga. His name does not appear in any Lancashire records. He is not mentioned in his father’s will. No newspaper articles report his relationship to his father except at the very last, a fleeting reference without comment in his obituaries. He was deliberately expunged from the family tree, the ‘Pedigree of Bullough’, hanging in Kinloch Castle. Effaced from Burke’s Peerage and from all family chronicles, it is only in the last five years that his existence as one of John’s sons has been rediscovered.

Swiss records show that he was born at the hotel then managed by his grandfather, the Bellevue, in Thun on 28 March 1880. In the UK census of 1881, three of the family are shown as resident at Rhyddings Hall: John Bullough, his wife Bertha and their daughter Bertha. Also listed are a maid and cook (both Scots5). George was presumably at boarding school. There is no mention of Edward, now aged one, or of a governess. Edward had presumably been left in Switzerland while her mother was attending the legal process for ending her marriage.

* * *

Edward’s story provides an interesting sideline – none of the Bulloughs can ever be considered to have led dull lives.

He spent little time in Thun after his mother divorced, for she moved to Dresden where he attended school. In 1902 he completed a four-year Master of Arts in French and German at Trinity College, Cambridge, and stayed on to teach. His gift for languages was exceptional. He had obviously picked up English either from his mother or grandfather, and he rapidly added Russian, Italian, Spanish and Chinese to his native German. His degree of fluency can be gauged by the fact that Cambridge awarded him a professorship in his ‘fourth’ language, Italian. He was one of two principal collaborators on the production of Cassell’s German Dictionary. As well as teaching he delved deeply into a study of aesthetics and psychology. There is a suggestion he may have worked as a spy in the Great War – he certainly served as a Lieutenant in MI5, or, officially, the Intelligence Department of the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve. He was highly regarded for his abilities, and not only was he a member of the mission which arranged for the surrender of the German fleet, he was also asked to interpret at the signing of the Peace Treaty in Kiel. In later life he was an ardent freemason. Then, never having shown any inclination towards established churches before, in 1923 he converted to Catholicism and, after retiring from Cambridge, devoted himself to serving the Church as a Dominican Tertiary.

He married Enrichetta Checchi, the only child of the internationally famous Italian actress, Eleanora Duse. They had two children who both joined the Dominican Order, undertook vows of chastity and adopted the names of saints (Brother Sebastian and Sister Mary Mark), thus adding another layer to the veils of secrecy begun by John Bullough.