Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

'It is impossible not to be thrilled by Edgar Wallace.' So said the blurbs of Wallace's own books. Indeed, he was a prolific author of over 170 books, translated into more than thirty languages. More films were made from his books than any other twentieth-century writer, and in the 1920s a quarter of all books read in England were written by him. His success is written in black and white, but his life got off to an inauspicious start. Edgar Wallace, the illegitimate son of a travelling actress, rose from poverty in Victorian England to become the most popular author in the world and a global celebrity of his age. Famous for his thrillers, with their fantastic plots, in many ways Wallace did not write his most exciting story: he lived it, and here Neil Clark eloquently tells his tale to allow you to live it too.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 579

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

NEIL CLARK is a journalist, broadcaster and award-winning blogger. He has contributed numerous articles to leading newspapers, such as The Guardian, Daily Express, Sunday Express, Daily Mail and The Spectator.

He is the author of Flying Ace: The Story of a Racing Legend (1992), Champion Jump Horse Racing Jockeys from 1945 to Present Day (2021) and a contributor to Great Racing Gambles and Frauds 2 (1992). He is a regular commentator on sport and current affairs on television and radio.

As a long-standing Edgar Wallace enthusiast, in 1993–94 he was chair and organiser of the Edgar Wallace Society.

Visit his blog at www.neilclark66.blogspot.co.uk.

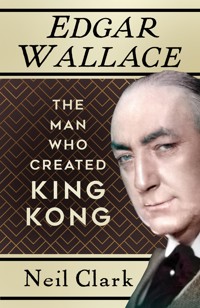

Front cover illustration: Edgar Wallace c. 1927. (Photo by Sasha/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

First published 2014 as Stranger than Fiction

This paperback edition first published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Neil Clark, 2014, 2023

The right of Neil Clark to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75249 895 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 A Birth in Greenwich

2 The Story of Polly Richards

3 A Docklands Childhood

4 The University of Life

5 ‘I’ll be a Great Man One Day!’

6 The New Recruit

7 Off to South Africa

8 Edgar Wallace: War Reporter

9 A Husband, a Father and a Newspaper Editor

10 The Special Correspondent

11 The Four Just Men

12 In Deepest Africa

13 Captain Tatham and Commissioner Sanders

14 Back on Fleet Street

15 The Curious Case of the Confession of Dr Crippen

16 More Bright Ideas

17 For King and Country

18 Jim

19 The Fiction Factory

20 Thrilling a Nation

21 Enter the Ringer!

22 People

23 King of the West End

24 Edgar Wallace: Film Director

25 Adventures in Germany and America

26 Hats Off to Edgar Wallace!

27 Edgar Wallace MP?

28 Edgar Goes to Hollywood

29 The Final Chapter

30 Edgar Wallace Lives On

Notes

Select Bibliography and Further Reading

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to my family: my mother Joan for her encouragement, reading through the book at various stages, and for her suggestions; my wife Zsuzsanna and father Roy for all their help and support.

Thank you to Dunja Sharif of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, for help and assistance with accessing the Hogan collection of Wallace material. Thanks to Roger Wilkes for his work on listing all the material.

Thanks to my commissioning editor, Mark Beynon, and all who have worked on the book at The History Press.

All biographers owe a debt to those who have written about the subject previously, and I would like to thank Selina Hastings, daughter and literary executor of the late Margaret Lane, for kindly giving me permission to quote, without restriction, from her mother’s 1938 biography of Edgar Wallace and also to reprint photographs from the book.

Thank you to Swami Dayatmananda of the Ramakrishna Vedanta Centre, Bourne End, Buckinghamshire for permission to include a photograph of what used to be Edgar Wallace’s house, Chalklands. Thanks also to Wheeler Winston Dixon and Sharla Clute of the SUNY Press and Mr Duff Hart-Davis for permissions. With grateful thanks to Reverend Michael Boultbee for permission to include his letter about his childhood recollections of Edgar Wallace, written in 1975.

I am grateful for the advice of Sir Rupert Mackeson and the Society of Authors.

I am indebted to the British Library, British Newspaper Archive, Jonathan Horne (special collections) at the University of Leeds, and the special collections at the University of Sussex and Oxfordshire Library services.

INTRODUCTION

Truth is stranger than fiction, and has need to be, since most fiction is founded on truth.

Edgar Wallace, The Man Who Knew, 1919

It is one of the most famous scenes in motion picture history. A gigantic ape, roaring defiantly, stands at the top of the Empire State Building and is attacked from all sides by fire from circling aeroplanes. King Kong caused a sensation when it first appeared on cinema screens in 1933, becoming the first film to open at the world’s two largest theatres – the Radio City Music Hall, and the Roxy, in New York – simultaneously. ‘The Strangest Story Ever Conceived by Man … the greatest film the world will ever see,’ the publicity declared. ‘For once the catch-lines were right,’ wrote film historian Denis Gifford, ‘in the history of horror movies, indeed of movies, King Kong still towers above them all.’1

More than eighty years on, the story of how the eponymous gorilla is captured on a remote island and taken to New York, where he escapes and causes havoc, still packs a punch. It’s not just a thrilling adventure tale and horror story, but a romance too – a modern reworking of ‘Beauty and the Beast’ that never fails to touch our emotions. There have been two film remakes, in 1976 and 2005, and a new musical version opened in Melbourne, Australia, in 2013 to widespread critical acclaim. In 1991, the 1933 film was deemed to fit the criteria of being ‘culturally, historically or aesthetically significant’ by the US Library of Congress, and was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry. But, while almost everyone knows the story of King Kong, and its place in cinematic history is assured, what is less well known is the almost equally fantastic tale of his English co-creator, who tragically died in Hollywood at the moment of his greatest and most enduring success. Writing the screenplay for Kong was the last major piece of work for Edgar Wallace, a man who packed into his relatively short time on earth enough achievements and experiences to fill several lives over.

Wallace worked as a printer’s assistant; a milk roundsman; a newspaper seller; a plasterer’s labourer; a soldier; a ship’s cook and captain’s boy on a Grimsby fishing trawler; a boot and shoe shop assistant; a rubber factory worker; a newspaper reporter; a foreign correspondent; a racing tipster; a columnist; a special constable; and a film producer and director.

The illegitimate son of a travelling actress, who left school at the age of 12 with no formal qualifications, he was also, at one point, the most widely read author in the world. Wallace made his name writing fast-paced thrillers, detective stories and tales of adventure. He wrote more than 170 books, and his work was translated into more than thirty languages. More films were made from his books than those of any other twentieth-century writer. He was the publishing sensation of the 1920s – in one year in that decade, one out of every four fiction books bought in England was by Edgar Wallace. If that wasn’t enough, he also wrote twenty-three plays, sixty-five sketches and almost 1,000 short stories. ‘Wallace brought the art of popular entertainment to a pitch which never before had been achieved by any other writer,’ wrote his 1938 biographer, Margaret Lane.2

Edgar Wallace’s work was devoured by people of all classes, nationalities and political persuasions. Among his millions of fans were King George V, British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, a president of the United States, and a certain Adolf Hitler who, it is said, owned copies of all of Wallace’s books.

The man born in poverty in south-east London, and whose mother gave him away to foster parents when he was just over a week old, became one of the biggest celebrities in Britain in the first third of the twentieth century.

He cut a flamboyant figure, chain-smoking cigarettes from his trademark 10in-long cigarette holder and being chauffeur-driven round London in a yellow Rolls-Royce. Wallace worked hard and played hard and was renowned not just for his industry but for his incredible generosity which knew no bounds. It was this open-handedness which meant that, despite his high income, Wallace died heavily in debt. However, he wouldn’t have minded too much as he was a man with big ambitions who did everything on a grand scale. The covers of his books often carried the proud boast of the publisher: ‘It is impossible not to be thrilled by Edgar Wallace.’ As I hope to prove, it is also impossible not to be thrilled – and inspired – by Edgar Wallace’s extraordinary life story.

1

A BIRTH IN GREENWICH

He lived for some extraordinary reason in Greenwich, in a side street that runs parallel with the river.

Edgar Wallace, The Twister, 1928

The year 1875 was one of the most eventful of the Victorian era. It was the year that Britain acquired a majority interest in the Suez Canal, Captain Webb became the first person to swim the Channel, William Gladstone resigned as Liberal Party leader and Gilbert & Sullivan’s earliest surviving opera, Trial by Jury, was premiered. Although life was still harsh for most people, things were improving – at least for those living in towns and cities.

Among the important pieces of legislation passed that year by Benjamin Disraeli’s reforming ministry was the Artisans’ Dwelling Act which enabled local authorities to purchase and demolish slums and insanitary property; and a ground-breaking Public Health Act which compelled local authorities to ensure adequate drainage and sewage disposal, and to collect refuse on a regular basis. Later in 1875, another sign of progress – Joseph Bazalgette completed his thirty-year construction of London’s sewers.

If we could magically go back in a time machine to the London of 1875, we’d no doubt marvel at the ‘new’ big thing in transport – horse-drawn trams on rails, which since 1870 had been challenging the supremacy of the horse bus. We’d also be curious to see lamplighters, carrying long poles with wicks at the end to light the gas lamps which lit the city’s streets, and ‘public disinfectors’ clad in white coats, dragging handcarts into which they would put contaminated clothing and other materials.

We’d be surprised at just how lively street life was compared to today, with the thoroughfares full of hawkers selling everything from fresh strawberries and jellied eels to medicines. If we fancied some entertainment, we’d have no shortage of options – in 1875 there were no fewer than 375 music halls in Greater London.

Some things from the modern world we would recognise. For example, in 1875 the London Underground, the oldest such railway in the world, was already 12 years old, although the Metropolitan and District lines are the only ones we would know today.

In 1875, London was, of course, not only the capital of Britain but the centre of a vast empire, which would continue to expand over the next half-century. It was into this great imperial metropolis, at No. 7 Ashburnham Grove, in an unremarkable street of terrace houses in Greenwich, that the subject of our story was born on Thursday, 1 April 1875.

The boy was born out of wedlock. His mother was Polly Richards, a kind-hearted travelling actress, and his father, Richard Horatio Edgar, was an actor and the son of Miss Marriott, the manageress of the theatre company for which Polly worked, and was already betrothed to another. Miss Marriot did not know of her son’s affair, putting Polly in a bind. Due to rejoin her theatre company in Yorkshire on 10 April, without the means to bring up the child herself, and determined to keep the identity of the boy’s father a secret, she had no option but to look for foster parents for her child. So it was that just a few days after his birth, the baby boy, wrapped in a white shawl, was taken from No. 7 Ashburnham Grove to his new parents, a fish porter and his wife who lived a few blocks away.

What odds would have been given that the child, born in such unpromising circumstances, would become the most-read author in the world, that this illegitimate son of a poor travelling actress would one day enjoy fabulous wealth, own a yellow Rolls-Royce and a string of racehorses, would know and hobnob with peers of the realm, and would entertain his guests lavishly at his own private box at Royal Ascot?

The phrase ‘rags to riches’ tends to be overused, but the story of Edgar Wallace is, in many ways, the ultimate rags-to-riches tale.

2

THE STORY OF POLLY RICHARDS

Holbrook had no illusions about the theatrical profession; he knew something of their lives, knew something of their terrific struggle for existence which went on all the time, except for a few favourites of the public …

Edgar Wallace, The Hand of Power, 1927

Polly Richards, Edgar Wallace’s mother, was literally a woman of many parts. She was born Mary Jane Blair, in White Street, in the St Thomas sub-district of Liverpool in March 1843. Her father was James Blair, whose occupation was recorded as ‘mariner’ on her birth certificate, and her mother, Charlotte Blair, nee Duffye.

Polly worked as a small-part actress and dancer, and in 1867 married a merchant service skipper named Captain Richards. But the union was ill-fated, and in January 1868, on his first voyage after his marriage, Captain Richards became ill and died, leaving Polly a widow and eight months pregnant at the age of 24. Polly had no option but to return to the stage (she changed her first name to ‘Marie’), but life was a terrible struggle. ‘How she weathered those first years of widowhood, living precariously on the fringes of the theatre, depositing her baby first with one lodging house keeper and then another while she worked, one can only guess; but with no beauty and no outstanding talent to recommend her she must have had a tedious and embittering struggle,’ suggests Margaret Lane, Edgar’s biographer.1

Nietzsche’s adage that ‘that which does not kill us makes us stronger’ comes to mind when we consider how Polly got through those years. She did survive; showing the same sort of perseverance demonstrated by her celebrated son whenever he met with what looked like insurmountable setbacks.

Polly’s lucky break came in 1872, when she met her saviour, the remarkable Alice Marriott, one of the mid-Victorian era’s best known Shakespearean actresses, and owner of a travelling theatre company. At the time Polly, in the words of Margaret Lane, ‘had reached the lowest ebb of disillusion and poverty, and was almost starving’.2 Aged 29, she was living with her child, Josephine, as a lodger in a cottage behind a public house which was next door to the Theatre Royal in Williamson Square, Liverpool. Miss Marriott and her company had come to play at the Theatre Royal which, in 1872, was celebrating its centenary. We don’t know the exact circumstances of the meeting between Marriott and Polly, but we do know that the kindly older woman took pity on the out-of-work and out-of-luck actress, and took her to her own lodgings and offered her work in her own company. Polly acted small parts in plays and also worked as a dresser.

There was, of course, the problem of what was to become of Polly’s little girl, Josephine, who was aged just 6 years. Miss Marriott suggested that she be put into the Sailors’ Infant Orphan Asylum in Snaresbrook and, when a vacancy occurred there, ‘Joey’ was duly sent off. Unsurprisingly, she was unhappy in her new environment and went on a hunger strike, causing great alarm to the orphanage authorities, who wrote to Polly requesting that she remove her child. Polly went to the orphanage by train and brought Joey back. Now, it wasn’t just Polly Richards who became part of Miss Marriott’s company, but her daughter too, and they both proved popular additions to the troupe. Lane quoted the testimony of Adeline, one of Miss Marriott’s two grown-up daughters, who told how the new recruit, ‘for all her sardonic reserve of manner, somehow contrived to be the life and soul of dressing-room parties, keeping them all in a roar with funny and improbable stories which she told with a disarming air of gravity and truth, watching her audience from under heavy eyelids, her face impassive.’3 It was later said of Polly’s son that he was the best raconteur in London, another quality he seems to have inherited from his mother.

The other two members of the Marriott company requiring mention are her husband, Robert Edgar, and her son, Richard Horatio Edgar. Like many husbands of strong, determined women, Robert Edgar seems to have been something of a waster. Given the formal title of ‘manager’, he blew much of the money his wife had earned on foolish financial speculations; thereby preventing his spouse from living out her final years in the comfortable retirement her hard work and her talent deserved.

Richard Edgar was handsome and charming; a talented actor in comedy roles, but also rather lazy and something of a lothario. His devoted mother was keen for her son to settle down, and decided to use Polly as a matchmaker. In the autumn of 1873, Polly presented a pretty young actress called Jenny Taylor, whom she had befriended on a trip to Scotland. Jenny passed Miss Marriott and her son’s seal of approval and was taken on as member of the company. The script should have continued with Richard Edgar and Jenny getting engaged, marrying and living happily ever after but, if that had happened, we would have no story. Richard and Jenny did get engaged and did get married4 but, before that, something else happened. The circumstances are unclear, but what we do know is that sometime in the spring or early summer of 1874 Richard Edgar had a sexual encounter with Polly Richards. So that, at the very time that Richard and her friend Jenny were announcing their engagement, Polly found herself pregnant – with the child of her patron’s son.

It is easy for us to imagine what might have been going on in Polly’s mind at this moment. She could tell Miss Marriott everything about the child and who the father was, but that would surely have sabotaged the wedding between Richard and Jenny. She might also have invoked the ire of Miss Marriott, even though that kindly woman would probably have shown her forgiveness. Polly decided the wisest course of action was to keep schtum, even though that would almost certainly mean her having to discard her child after it was born.

At Christmas, she absented herself from the company and took lodgings in Greenwich. Heavily pregnant, she not unsurprisingly failed to attend Richard and Jenny’s wedding, which took place in late March. Just a week after his marriage, on 1 April 1875, Richard’s son, and the subject of our story, was born. Polly and Richard’s little boy was baptised by a curate named V.P. Hobson in St Alfeges Church, Greenwich, on 11 April. He was given the name ‘Richard Horatio Edgar Wallace’ with Walter Wallace, comedian, recorded as his father and ‘Mary Jane Wallace’ as his mother.

So, who was Walter Wallace? ‘No amount of research has yielded a clue to the mysterious “Walter Wallace, comedian” in the Greenwich Register, and it is more than probable that he never existed,’ wrote Margaret Lane,5 who noted that no one still living at the time of writing her book (1938), and who was associated with the Greenwich Theatre or Polly Richards, could remember such a person. Today, we have computer technology and websites like FreeBMD6 to help us search for people born after 1837.

Records show that ten people named simply ‘Walter Wallace’ were born between June 1838 and December 1854, with a further five having their second names given. It is perfectly possible that Polly Richards could have come across one of these ‘Walter Wallaces’ in her life and decided to make him the father of her child, but the likeliest explanation is that she simply made the name up, giving her son a fictitious father who could never be traced.

Having had her child baptised, Polly now had to place him with foster parents. Lane tells us that Polly’s midwife had recommended a fish porter and his wife, George and Clara Freeman, who had already brought up ten children of their own and who lived about a mile away in a four-roomed cottage in Norway Court, Deptford. Lane tells us that Polly went round to ‘interview’ Clara Freeman. ‘The cottage, though overcrowded, was spotlessly clean, and Polly was received in a dark but proudly kept front parlour with plants in the window and a fringed cloth on the table.’7 Payment of 5s a week for the child’s upkeep was agreed, and the deal was done.

In Edgar Wallace’s own version, though, it was the Freemans who made the first move:

Happily, there was a philanthropist who heard of my plight, and having for the workhouse the loathing which is the proper possession of the proud poor, he dispatched Clara to fetch me. ‘She’s adopted’, said Mr Freeman, an autocrat in his way. Nor when he discovered that he had been mistaken as to my sex did he vary his humane decision.8

Why is there a discrepancy between the accounts of Margaret Lane and Wallace, on how he came to be adopted? It is revealing that Wallace’s mother gets no mention at all in his autobiography, written in 1926, and it is likely that he still felt hurt over her actions. For Wallace, it was the Freemans who came to the rescue of a discarded child, while from Lane’s point of view, Polly Richards comes over as dutiful for making sure her son had a good home.

Whatever the precise steps were, after the agreement was made between Polly and the Freemans, Milly, one of the Freeman children, visited Ashburnham Grove the following morning to take little Richard Horatio Edgar Wallace away to his new home. What Polly must have felt at bidding farewell to her baby we can only imagine, but she had little time to feel sorry for herself as she desperately needed to earn money. She left Greenwich for Huddersfield to rejoin Miss Marriott’s company, playing at the Theatre Royal.

3

A DOCKLANDS CHILDHOOD

Somewhere in the east the sun was rising, but the skies were dark and thick; lamps burnt on river and shore. Billingsgate Market was radiant with light, and over the wharves where cargo-boats were at anchor white arc lights stared like stars.

Edgar Wallace, The India Rubber Men, 1929

Clara Freeman and her husband welcomed the new addition to their family with ‘the total generosity of the very poor’, to use the memorable phrase of the journalist James Cameron, the writer and presenter of a BBC documentary on Edgar Wallace which was broadcast in 1976.1

George Freeman was a strict but kindly man who worked as a fish porter in Billingsgate Market, to where he would head at three o’clock every morning, come rain or shine. He was not only a Freeman by name, but also a ‘freeman of the City of London’, a liveryman of the Haberdashers’ company, who proudly claimed that he could trace his ancestry back through 500 years of city records. He was certainly a respected local figure. ‘He never did a crooked thing in his life … He lived a Christian life, was just to all men, fearless – he could not lie’, Wallace later wrote of his adopted father.

A photograph of Mr Freeman with his bowler hat, waistcoat and overcoat, cravat and goatee beard confirms the impression of a decent, serious man – the very model of Victorian propriety. Occasionally though, this devout paragon would let his hair down. ‘He used to “break out” about twice a year and drink brandy,’ Wallace recalled, ‘then was the Testament laid reverently aside, and he would fight any man of any size and beat him. Once he fought for two hours, perilously, on the edge of a deep cutting.’

His wife, Clara, who bore him ten children, was described by Wallace as ‘the gentlest mother who ever lived.’ The photograph (Plate No. 3) of her shows a shortish woman with a serious but kindly face, dressed in a bonnet and mantle. Someone who, like her husband, could no doubt be strict when the need arose but, like George, had a heart of gold.

Dick Freeman – the name his foster parents gave him – was surrounded by warmth and affection in his new home, but his time at the Freemans’ could have come to a relatively early end when he was just 2 years old. Polly came to visit, to see her child, and returned again not long afterwards. It was during this second visit that she told Mrs Freeman that she could no longer afford to pay Dick’s keep and so had made arrangements for her son to be ‘taken in somewhere’. The prospect of her beloved foster child going to an orphanage appalled Mrs Freeman, and her daughter Clara, who was present at the meeting, and they offered to formally adopt the child. So it was that little Dick Freeman became an official member of the family.

Polly still kept visiting Dick frequently throughout his childhood, according to her granddaughter, Grace Fairless: ‘I heard from her own lips that he had been taken by her to see his sister [Josephine] at school, and [s]he told me how he had looked up to her and thought how sweet she was because she had given him sixpence for himself.’2

Of the Freeman children, it was Clara who became Dick’s closest ally. Like her sisters, Clara had been sent off at the age of 12 into domestic service – the standard fate which befell girls of her class at that time. Margaret Lane surmises that Clara championed the cause of her little brother because she had so little youth of her own and ‘saw in the adopted boy possibilities of a richer and more promising life than she would ever know.’3 Clara would renew her friendship with Dick when she returned to her parental home during intervals between jobs. They would go for walks together by the river and explore the environs.

Although Norway Court and the surrounding area was far from salubrious, it was nevertheless an interesting place for a young boy to grow up. ‘Greenwich had a maritime flavour in those days. It was a town of blue-jerseyed men, and in every other house in our neighbourhood was the model of a full-rigged ship,’ Wallace recalled. ‘That riverside landscape was the first he [Wallace] ever knew’, wrote James Cameron, ‘Exploring the grey edges of the Thames, the tidal river where the ships still came. All the wharves and alleys and by-ways of Deptford and Bermondsey, all the waterfront smells of spice and sail cloths – that was the background of life – sombrely exciting.’

Billingsgate fish market4 where his foster father worked as a fish porter5 played an important part in Wallace’s early life. When he was old enough, Dick would sometimes accompany Mr Freeman to work. ‘How those men worked!’ he recalled, ‘Their hobnailed boots rattling over the slippery pavement of the market – along the planks that spanned between wharf and GIC boats that lay alongside.’ Dick would stand and watch at the quayside as the boats unloaded their catches: ‘Ice-rimed boats from Grimsby, tubby eel boats from Holland, big ship and little ship. “Collectors” that had come rolling from the Dogger Bank with their holds packed with silvery fish that was officially “alive”.’

It was this colourful, bustling, Thameside world, with ships sailing to and from exotic parts of the world and its warehouses laden with tea and spices and sailors singing shanties in bars, which arguably first fired Dick Freeman’s imagination and his lifelong love of adventure. Growing up in London’s docklands not only gave him a taste for travel, it also started his enduring fascination with crime. ‘My first vivid recollection in life is one of a sort of possessive pride in prison vans. The gloomy Black Maria that rumbled up the Greenwich Road every afternoon,’ he wrote.

The Freeman sons were often in trouble with the police – which wasn’t hard in those days, when the working classes didn’t have to do too much to feel the long arm of the law. ‘All his life he hated policemen and he had a passion for fighting them,’ Wallace said of his step-brother Harry. When he was 10, Dick was involved in criminal activity for the first time and he became an associate member of a gang of burglars. ‘I never took part in any of the raids carried out by a desperado very little older than myself, but I received a little of the loot and regretted it was not more useful,’ he confessed many years later.

Afterwards, though, he found himself on the right side of the law. He was approached by a man who asked Dick to buy cigarettes for him, a penny’s worth at a time. He gave Dick ‘nice new florins’. Dick took one of the florins to a policeman, and asked him if the money was ‘snide’ i.e. counterfeit. The policeman broke the coin with his finger and thumb and pronounced it snide. The cigarette buyer was arrested, and the magistrate duly praised Dick, saying he was a smart little boy. The incident led to a historic first, as the News of the World report of the crime was the first of many times that Dick Freeman was to see his name in print. The little boy who would one day be a Fleet Street legend, under the name of ‘Edgar Wallace’, had made his newspaper debut.

After the young Dick Freeman had attended infant classes, at St Peter’s Infant School in Thames Street, the Freemans moved from Norway Court to Camberwell. For Dick, that meant going to Reddin’s Road Board School. Primary education had only been established on a national basis by the Education Act of 1870, passed by the Liberal government of William Gladstone. The Act established ‘School Boards’ which were empowered to provide schools paid for out of the local rates in areas where there was inadequate provision. Although the Act had its critics, there’s no doubting the impact it made. We see this dramatic transformation with Edgar Wallace’s own family – he went on to become a great writer, while neither of his beloved foster parents could write.

Not that Dick greatly appreciated the effects of the 1870 Education Act at the time, ‘Every morning when I turned the corner of Reddin’s Road, Peckham, and saw the board school still standing where it did, I was filled with a helpless sense of disappointment,’ he wrote. The ‘big yellow barracks of a place’ was, for Wallace, and no doubt for other children too, a grim, uninviting place. ‘… and the fires that were never lit, and the evil blackboard where godlike teachers, whose calligraphy is still my envy, wrote words of fearful length. The drone of the classrooms, the humourless lessons, the agonies of mental arithmetic and the seeming impossibilities of the written variety.’

It was common for there to be as a many as fifty children in one class, and the building itself was gradually sinking, having been built – so the story went – on an old rubbish tip. It was all a far cry from the modern schools of today with their computers and comfortable centrally-heated classrooms, but, as much as the young Dick Freeman hated his board school days, there were positives too. He learnt to write his name, to the great pride of his father. ‘George gave me a penny and carried the scrawl to the market for the admiration of his friends,’ he recalled.

And not all lessons were to be dreaded. The brightest school day of all for Dick was when a teacher named Mr Newton read out stories from The Arabian Nights to the class:

The colour of the beauty of the East stole through the foggy windows of Reddin’s Road School. Here was a magic carpet indeed that transported forty none too cleanly little boys into the palace of the Caliphs, through the spicy bazaars of Bagdad, hand in hand, with the king of kings.

Wallace was not the only writer to be inspired by The Arabian Nights; others include Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Tolstoy, Alexander Dumas, Wilkie Collins and many romantic poets.

It was also at board school that Dick was first introduced to the works of William Shakespeare, starting a lifelong love affair with the works of ‘The Bard of Avon’. ‘I learnt whole scenes of Macbeth and Julius Caesar and Hamlet and could recite them with gusto on every, and any, excuse.’

It was clear to George and Clara that young Dick Freeman had a talent worth nurturing. Their other children had left school at 10, but the Freemans agreed to Dick staying on until he was 12. Once again, this demonstrated their kind-heartedness as it meant they would have to wait another two years before their foster son brought a wage in to the household.

Not that Dick wasn’t kept busy outside of the classroom. He helped his parents out as much as he could, and did most of the shopping. ‘Up before breakfast, and with a mat bag ranging the Old Kent Road for the day’s provisions … A pound of sixpenny “pieces” from Mills the butcher, two penn’orth of potatoes from the greengrocer’s, a parsnip and a penn’orth of carrots – I came to have a violent antipathy to Irish stew,’ he recalled. After he’d done the shopping, it was time to head off for school.

In the second chapter of his autobiography, Wallace lists what he learnt at board school. It’s an interesting historical document, as it shows us the sort of things that a working-class child in Britain would have been learning in the 1880s:

Geography: Roughly, the shape of England; nothing about the United States, nothing about the railway systems of Europe. I learnt that China had two great rivers, the Yangtze-kiang and Hoangho, but which is which I can’t remember. I knew the shape of Africa and that it was an easy map to draw. I knew nothing about France except Paris was on the Seine. I knew the shape of Italy was like a top-booted leg, and that India was in the shape of a pear; but except that there had been a mutiny in that country, it was terra incognita to me.

History: The ancient Britons smeared themselves with woad and paddled round in basket-shaped boats. William the Conqueror came to England in 1066. Henry VIII had seven – or was it eight? – wives. King Charles was executed for some obscure reason, and at a vague period of English history there was a War of the Roses.

Chemistry: If you put a piece of heated wire in oxygen – or was it hydrogen – it glowed very brightly. If you blow a straw into lime water, the water becomes cloudy.

Religion: No more than I learnt at Sunday school.

Drawing: Hours of hard work I made an attempt to acquire proficiency in an art for which I had no aptitude.

Arithmetic: As far as decimals. In those days book-keeping was not learnt at school. You might say that all the knowledge I acquired from my lessons in arithmetic was the ability to tot columns of figures with great rapidity.

Wallace then gave his general reflections on a board school education:

I think I would undertake to teach in a month more geography than I learnt in six years.

… the system is as wrong as it can well be, and hour after hour of time is wasted in inculcating into a class of fifty, knowledge which is of no interest whatever except to possibly two or three.

It’s important to note that board school was not the only ‘school’ which Dick attended at this time. There was also Sunday school6 where children not only learnt stories from the Bible, but played games, acted in plays, sang songs and generally had a very enjoyable time. It was at Sunday school that Wallace learnt the story of ‘Christie’s Old Organ’. ‘The moral of the story was that one ought to be kind to people less fortunate than oneself,’ he later recalled. It certainly made a big impact on Dick – someone who, when he grew up, would become renowned for his generosity. ‘The complex introduced into my mental system by “Christie’s Old Organ” has cost me thousands of pounds,’ he ruefully reflected, ‘I have often wished I had begun my course of reading with “Jack Sheppard”.’

Wallace, throughout his life, was never religious, yet he enjoyed the more relaxed atmosphere at Sunday school far more than his days at Reddin’s Road. Every year there was the annual excursion, where the children who were regular scholars would get a day out in the country – including food – for sixpence. Dick loved these trips, so he decided to get on as many of them as he could. One became a ‘regular’ scholar by being on the books of a Sunday school for one month, so Dick, with characteristic resourcefulness, set out to enrol in as many different Sunday schools as he could. ‘In the course of the years I worked almost every Sunday school in the neighbourhood,’ he recalled.

As deficient as was the education which Dick Freeman – and other working-class children of his generation – received in the 1880s, the combination of Sunday school and board school was still a marked improvement on what had gone before. In the thirty years’ existence of the school boards, some 2.5 million new places in new buildings were provided. Let’s suppose that the 1870 Education Act had not been passed, and that a nationwide system of elementary education had not come into effect for, say, another twenty years – then the phenomenon of Edgar Wallace, the illegitimate working-class son of a travelling actress, who rose to become the most widely read author of the world, would simply not have happened.

Before Wallace, one can think of no prolific writer who came from his social background. He was the trailblazer for a class of people who, for centuries, had no voice. They had stories to tell, stories at least as interesting as the upper or middle classes, but they were unable to write them down. W.E. Forster’s Act did not go far enough – we had to wait until 1902 before local education authorities were empowered to provide secondary schools – but it did at least ensure that a whole new generation of working-class children learned to read and write, and had exposure to classic literature. In The Naval Treaty, by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes is travelling with Dr Watson on a train going past Clapham Junction, ‘Look at those big, isolated clumps of buildings rising up above the slates, like brick islands in a lead-coloured sea.’ Holmes declares. ‘The Board schools’, Dr Watson replies. ‘Lighthouses, my boy! Beacons of the future!’ exclaims Holmes, ‘Capsules with hundreds of bright little seeds in each, out of which will spring the wiser better England of the future.’

As we have seen, Dick Freeman’s working career began while he was still at school, running early morning errands for his parents. In the summer holidays of 1886, when he was 11, he embarked on another job – selling newspapers at Ludgate Circus. He didn’t tell his parents. He sold copies – on a sale or return basis – of The Echo, which he described as ‘a bilious-looking sheet that was remarkable for its high moral tone and the accuracy of its tips.’ His pitch was outside Cook’s Travel Agency, very close to the wall which today carries a bronze plaque to his memory. He later wrote:

It was an enthralling experience. I stood in the very centre of London. Past me rumbled the horse buses, the drays and wagons of the great metropolis. I saw great men, pointed out to me by a queer old gentleman in a frowsy overcoat and top hat who haunted Ludgate Circus. Sala – Mr Lawson, who owned the Telegraph … Henry Irving driving in a hansom cab with a beautiful lady called Ellen Terry (they were coming from St Paul’s). I was very happy and grateful that I had the opportunity of seeing such people.

Dick loved his job, but he still had one more year of school to go. So, whenever he could, he played truant in the afternoons when the new school term began and made his way up to Ludgate Circus. Selling newspapers in the winter was not as much fun as in the summer, trade was slack and there was the cold to deal with too. Always the great improviser, Dick found a novel method of keeping warm. As he stamped his feet he would recite the quarrel scene from Julius Caesar. What, I wonder, would the purchasers of the Echo have thought of the young lad, quoting word for word from the works of William Shakespeare?

Dick’s earnings averaged about 3s a week – which he spent on ginger beer, toffees and the theatre. But he got from the experience far more than that. Selling newspapers had kindled in him a love for newsprint – and for the sights and sounds of Fleet Street. In a little café, close to the Glengall Arms where Mr Freeman would go drinking, Dick would indulge in his love of the written word with the proprietress, a young woman called Mrs Anstee, who shared his passion for books and newspapers. They would read out loud to each other – and formed quite a bond.

Today, a friendship between a 12-year-old boy and a young married woman, brought together by their love of reading, might seem rather strange, but this was the 1880s, an age where reading for pleasure – and for self-improvement – was becoming hugely popular.

Margaret Lane records that when the Free Library in the Old Kent Road opened, Wallace would carry round the books he’d borrowed, ‘selected at random from the library catalogue’, to show to Mrs Anstee.7 He did the same with the second-hand books he bought. Mrs Anstee cut an attractive figure, and was a big influence on Dick. ‘She was the best and most stimulating companion possible for a child aching for something to try his wits upon, and with no one, beside herself, to encourage his eccentric appetite for reading’, says Lane.8

Going to Mrs Anstee’s shop also brought Dick closer to the world of the theatre. Her husband, Fred, was a part-time scene-shifter at the Gaiety Theatre in the Strand. Dick would sometimes go to work with him to run errands and do odd jobs. His love of the theatre was so great that he would do anything just to be inside the building. Mr Anstee was also able, sometimes, to get complimentary tickets to shows, and so Dick was able to go and watch performances from the gallery with Mrs Anstee. It wasn’t the only source of free tickets, sometimes he’d get them from Polly Richards too, and when the tickets arrived he’d go off to watch shows with Mrs Freeman, who was just as excited as he was. Even when there were no free tickets going, Dick would still save up and use any money he had to indulge his passion.

Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee was celebrated in 1887, and there was a special treat from Her Majesty for the board school children – a day off school to enjoy the occasion. ‘I went to Hyde Park labelled, drank sweet lemonade, cheered the wrong lady in the royal procession, and was awarded a jubilee mug shaped like a truncated cone.’ Wallace recalled, ‘I won three others in the train home by tossing, but I had to surrender them to the enraged parents who were waiting at Peckham Rye to welcome the adventurers home.’

With his school days coming to an end and the world of full-time work looming, George and Clara Freeman decided to give their adopted son a holiday. Again, this shows their wonderfully generous nature. Neither the Freemans nor their children had ever had a holiday in their lives – but this didn’t stop them wanting Dick to enjoy things they had done without. A nephew of George Freeman’s – a certain Mr Frisby – had moved to Dewsbury in Yorkshire, where he had a confectionary store. He came back down to London with his daughter, Lizzie, who was appearing at a choir festival at the Crystal Palace, and paid a visit to the Freemans. Frisby took a shine to Dick and suggested that, when his schooling had finished, the boy go up to Dewsbury for a holiday.

For Dick, it was his first trip out of the capital. He spent a happy three weeks in the confectioner’s shop – what a treat for a sweet-toothed boy of 12! – and enjoyed playing with the Frisbys’ seven daughters. He was also taken down a coal mine – Combs Pit – another big adventure. The Frisbys were sorry to see Dick go, and Dick himself was sad to return to London, having found West Yorkshire a very exciting place indeed. But now, after his summer holiday, it was time for him to enter the world of work in earnest.

4

THE UNIVERSITY OF LIFE

Of his life in London as a boy little is known. He worked, that is certain. But he was never more than two or three months in any one job. I have traced him to printers, shoemakers, and milk vendors. He seemed to be consumed with a spirit of restlessness which made the monotony of any form of employment maddening.

Edgar Wallace, Eve’s Island, 1926

Before Dick began work, he had to secure a copy of his birth certificate to show to his employers. Freeman was now ‘Richard Horatio Edgar Wallace’ and he took great pride in writing his new name.

His experiences as a newcomer in the labour market of late 1880s London tells us much about the grim working and employment conditions that ordinary people had to put up with 130 years ago, in what was the richest country in the world. Dick’s first full-time job was working in a printing factory, which made paper bags, in Newington Causeway. He was paid 5s a week, but during the first three weeks of his employment, 5s was deducted from his wages as a guarantee that he would not leave without giving due notice.

The work itself involved Dick standing by a lithographic machine from eight o’clock in the morning until five o’clock at night, taking off the paper bags as they were printed. Although he wore a black apron, his face still grew black as the day progressed. When bags with gold lettering were printed, he would come home with ‘gold’ dust on his boots.

One day Dick failed to turn up for work. When he came the next day he was paid the money owing to him and shown the door. The company refused to return to him the 5s deposit. Most young men, faced with this ending to their first job, would have been cowed and accepted their ‘punishment’ without too much argument, but Dick – to his credit – was having none of it. He reported the matter to the first policeman he met – ‘a fat man with cheeks that overhung his neck’ – and the sympathetic law enforcer told him that the company was in the wrong. ‘They’ve got no right to keep your money and you can’t sign anything away because you’re a minor,’ PC Harry Curtis-Bennett declared. Wallace told the policeman that he was indeed 12 on his last birthday, but notwithstanding the new information, he was advised to take out a summons. Wallace went to the magistrates’ court, told them about his case and then took out a summons – which cost him 1s – against his former employer. He conducted his own case in court, won the lawsuit – and got back his 5s.

This incident is revealing, since it shows to us once again the extraordinary self-confidence that Dick possessed. How many 12-year-old working-class boys would have had the courage to take their former employer to court, and to conduct the case themselves? Throughout his life, whether as Dick Freeman or Edgar Wallace, he refused to be intimidated or depressed by any obstacles or setbacks – on the contrary, he saw them as challenges to be overcome.

His experience in court also cemented his belief that, however unjust individual employers might be, the British justice system was essentially a fair one. We have already seen that he was praised as a smart little boy by a magistrate in the case of the snide florins, now here he was winning a court case all on his own. His experience also strengthened his positive view of the police force. ‘I have always had a blind faith in the police,’ he wrote, when recalling the incident. When Dick left the courtroom having won his case, a policeman with a broken nose approached him and asked if he had used to be called Freeman. Dick admitted that he had. ‘Your brother Harry done that,’ the policeman declared, pointing to his broken nose; but there were no hard feelings – Dick and the policeman went to have a cup of tea together in a café, and the latter paid.

Dick next found another job as a printer’s boy – this time with a company called Riddle and Couchman’s. This one he enjoyed rather more than his first job. ‘I was in the paper store and it was very interesting,’ he wrote. ‘Have you seen electric sparks come from between two sheets of paper after they have been hauled under a hydraulic press? Did you know that you could cut your finger to the bone on the sharp edge of paper?’ he asked the readers of his autobiography.

Again, though, the job didn’t last long. There were strikes, and all the boys – except Dick – walked out. That didn’t go down too well with his fellow workers, and Dick made a ‘dramatic exit’ from his workplace by way of the paper chute. ‘The boys were enthusiastic but I was out of work.’ Undaunted, he got another job with a printers. This one lasted for all of two weeks. The company in question printed railway timetables, and Dick had to carry large parcels of railway printing to various offices. Unsurprisingly, he didn’t feel that he had found his life’s vocation. When he left this job, Wallace decided to go back to his ‘old love’ – selling newspapers. ‘W.H. Smith provided me with a peaked cap, and on the wind-swept railway platform at Ludgate Hill and St Paul’s I promoted the sale of newspapers in a perfectly respectable manner.’

But this was a tough assignment too – there could have been few colder spots in the whole of London than where Dick had his pitch. It wasn’t long before he swapped the job for one working in a cheap boot and shoe shop in Peckham, which at least had the benefit of being indoors. Dick’s main responsibility was to mark the soles of new shoes with their selling prices, he wrote:

It was one of those multiple shops with branches in various poor districts. On Saturday nights you could earn an extra shilling by attaching yourself to one of the branches. In a clean, white apron, I sold tins of blacking to the ladies of Peckham, and tins of dubbin to the horny-handed male saunterers. I drew attention to delightful slippers for women, and hooked down dangling hob-nailed boots for the inspection of hardier citizens.

Although the job was a reasonably secure one, and not as physically arduous as ones which had preceded it, Dick soon grew bored of it. He handed in his notice and got a job working as a ‘hand’ in a rubber factory in Camberwell. ‘I, who had started life as a furtive seller of newspapers, had found my proper place in the industrial scheme.’ The job involved making mackintosh cloth. The hours were long, but it was an educational experience for Dick to say the least:

At the rubber works was a bitter man who taught me something. He was bitter about everything – his home, his work, the beef sandwiches his wife packed for him, my incompetence (I was his assistant), his grinding employer. I sat down one morning in the breakfast hour and puzzled through, without assistance, to the genesis of bitterness. I was so full of my unaided discovery that I fell upon him the moment he came in from the yard. ‘You’re sorry for yourself’, I said, with the air of a savant revealing a great discovery. He was carrying a great roll of damask and hit me over the head with it. Thus I learnt two things: never to be sorry for yourself; never to tell people unpalatable truths unless you are in a position to hit them back.

Dick also learnt how to get drunk on the cheap at the factory. ‘Rubber was dissolved in naphtha. By leaning over the vat in which the process was in operation and breathing in the naphtha fumes, it was possible to get pleasantly and even hilariously intoxicated,’ he explained. But there was a downside too, ‘You could also get dead. I had many a pleasant jag until one day it made me very sick.’

It was while working at the Camberwell rubber factory that Dick tried his hand at writing poetry for the first time. He composed rhymed couplets, poking fun at his self-pitying boss. Unsurprisingly, it didn’t go down too well and another job ended. It was back to shoes again – this time making boot heels by pasting scraps of leather together in a mould. But, while work was a large part of his life, it was not the only part. Whenever he had any spare time, he would indulge his love of reading. ‘When I left school I continued my reading education with the aid of penny dreadfuls and very wholesome and moral stories they were,’ he recalled in a 1926 article entitled ‘The University of Life’:1

There was a series called ‘Handsome Harry’ and another called ‘Jack Harkaway’; both made me hungrier for further conquests of the written word. I read everything that Henty wrote. Ballantyne was another potent influence, notably ‘The Young Fur Traders.’ Then I came upon Jules Verne, to have my imagination stimulated by ‘The Clipper in the Clouds.’ Those writers did more for the past two generations than many a man who has had monuments put up to him since.

There were other activities too to keep him fully occupied. The temperance movement’s aim was to rid the scourge of alcoholism from working-class communities by encouraging people to take the ‘pledge’ to abstain from drinking the ‘Demon Run’ and other noxious liquids. The movement was at its peak in the 1890s, and Dick, through his best friend Willie Ramsey – another printer’s boy – was introduced to it. As Margaret Lane explains, there were solid reasons why the movement would have appealed to Dick:

Dick himself in his younger days had spent hours, miserable and peevish, standing outside the swing doors of saloons, waiting for ‘Father’ to reappear and be steered home and his ears were filled with the moan of Mrs Freeman. Harry Hanford, Clara’s milkman husband, alternated blithely between crusading teetotalism and passionate bouts of drink, and ‘old Campbell,’ the umbrella-maker across the road, could always be relied on to entertain the boy with hair-raising stories of eternal fires awaiting the drunkard.2

At the age of 15, Dick signed ‘the pledge’. ‘As I did not even know the taste of strong drink, I signed readily,’ he wrote. In any case, Dick, with his wonderful imagination, positive mindset and unquenchable appetite for life, did not have the sort of character which seeks solace in alcohol. Life was exciting enough as it was – so why seek to be transported to another world by getting drunk? As we shall see later, he did become a man of addictions – smoking around eighty cigarettes a day, and drinking numerous cups of tea – but tobacco and caffeine were substances which kept him in the here and now, and didn’t leave him with a sore head in the morning.

The Christ Church Bermondsey Temperance Society wasn’t all about lecturing people about the evils of alcohol, there was a lighter side to it too. There were dances held in the winter and there were cricket and football teams attached to the society. Dick and Willie Ramsey spent their Saturday afternoons in both summer and winter playing for the teams. There were political meetings, and it was here that Dick – who just forty years later would be a Parliamentary Candidate himself – first experienced the rough and tumble of politics. Those who think politics is a dirty enough game today may be relieved to know that it was no less dirty in the 1880s. Dick and Willie were paid 1s a night to canvass for the local Rotherhithe Liberal and Radical Association, and part of their duties involved helping to break up any local Conservative meetings. Dick was to stay loyal to the Liberals all his life.

The Temperance Society wasn’t Dick’s only outside interest, he and Willie also enrolled in the local St John Ambulance Brigade. There, they learnt first aid and how to roll bandages and set splints. ‘It was good enough fun at the time and something to do, but for Dick at least this amateur training was to prove important,’ records Margaret Lane, ‘several years later, bored with the heavy routine of army life, he was to remember his own deftness with splints and bandages and the flattering approval of the St John Ambulance instructor, and apply for a transfer that permanently affected his life.’3

One is impressed with the sense of purpose that Dick possessed, and the way he put every experience to good use. He was already gathering, consciously or not, material which he would use when it came to writing his stories. The real-life ‘Kidbrooke Murder Case’ could have been the spark that kindled Dick’s interest in detective fiction. The grisly murder of a domestic servant, Jane Maria Clouson, took place four years before Dick had been born, but was still unsolved at the time he and his best pal Willie were keen to play ‘detectives’. Clouson had been found by a policeman, having been badly beaten by a hammer in Kidbrooke Lane, Eltham, and had died five days later from her injuries. Her murder gripped the public’s attention, and particularly those living in south-east London.

Clouson had lived in No. 12 Ashburnham Road, very close to where Dick had been born, so it was natural that he would take an interest in the case, and he and Willie set out to try to solve the mystery. Margaret Lane records:

While the hue and cry was on they went up on the Heath [Blackheath] after dark nearly every night, pretending to discover clues and hunt for the murderer, and taking care to keep prudently close to each other until it was time to go home to the Freemans’ kitchen and the solid comforts of strong tea and a bloater.4

Although they didn’t succeed in bringing the killer of Jane Maria Clouson to justice,5