Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

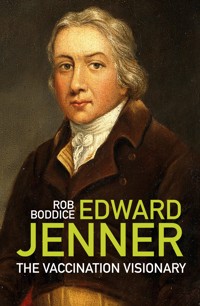

Edward Jenner is a giant of modern medicine. Throughout history, smallpox had plagued humanity with disfigurement, blindness and death. It was an incurable blight, the suffering of which Jenner helped to end. Surmising from the immunity of milkmaids that cowpox might be some defence against the ravages of smallpox, in 1793 he took some of the matter from a human case of cowpox and inserted it into the arm of a young boy. To test this, the first human-to-human vaccination, he subsequently inoculated the boy with smallpox itself, and found him to be immune from the disease. In 1979 smallpox was declared extinct. In this concise biography, Rob Boddice tells the story of Jenner's life, his medical vision and his profound legacy. It is a story that encompasses revolutions in medical experimentation, public health provision and the prevention of other diseases, from anthrax to measles, but above all it highlights the profound impact that Jenner's vision has had upon humanity's battle against disease.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 114

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Cover image courtesy of Wellcome Library, London.

pp. 6–7: James Gillray, ‘The Cow-Pock – or – the Wonderful Effects of theNew Inoculation!’ 1802. (Wellcome Library, London)

First published 2015 as Edward Jenner: Pocket Giants

This edition first published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Rob Boddice, 2015, 2023

The right of Rob Boddice to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75096 685 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Introduction: The Jenner Legend

1 Going Cuckoo

2 A Brief History of Smallpox

3 Inspiration

4 Hero?

5 Villain?

6 Tragedy

7 Legacy

Timeline

Abbreviations

Notes

Further Reading

Web Links

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Introduction

The Jenner Legend

The instrument in the hands of a gracious Providence.

John Baron, 18381

Edward Jenner was the protégé, at first directly and latterly by correspondence, of John Hunter, the famous surgeon, scientist and observer. John Hunter’s maxim for life, as for scientific inquiry, was ‘Do, don’t think’. His favourite pupil, Edward Jenner, certainly did.

Not all the doing was great and good. Jenner is immortalised as the man who made it possible to rid the world of one of its greatest scourges: smallpox. But along the way there was a whole host of experimental gambits, intuitive flights and spontaneous decisions. The spirit of scientific and medical investigation by induction was alive and well with Edward Jenner. Animated by scientific curiosity, without much obvious personal ambition, and driven by the energetic counsel of his mentor Hunter, Jenner shot, poked, boiled and pricked his way through a life of rural experimentation. One such experiment would provide proof of the concept for human-to-human inoculation of cowpox, which in turn provided immunity from smallpox. Jenner named the cowpox virus Variolae vaccinae, or smallpox of the cow, from which he derived the word ‘vaccine’. But to get to this breakthrough, which came well into Jenner’s middle age, we must first follow the spirit of trying things out that defined his earlier life.

To tell the life story of Jenner in this way cuts against the grain of typical narratives of his heroic life. Jenner has been – at least in the popular imagination – remembered as the saviour of more lives than any other single medical doctor. We know him as having rid the world of a terrible plague through a genius of daring experimentation, controlled trials and an indefatigable hard-nosed activism. Without these things vaccination would not have gained traction within the medical community and the global population at large. Received wisdom is that Jenner was without pecuniary interest, working for the benefit of humanity at great personal cost. He is remembered for qualities that set him apart from many of his peers. Such a rare and noble nature is the stuff of heroes.

This line of thinking has come down to us from the first memorialisation of Jenner’s life, published by his friend and colleague John Baron in 1838, some fifteen years after Jenner’s death. Baron was an uncritical disciple; his work was more hagiography than biography. It is filled with an expansive history of smallpox itself, and extensively documents the failings of all of Jenner’s opponents. While important for some of the essential details of Jenner’s life that are unobtainable elsewhere, one finds little left in the bag after shaking it free of detritus. The letters it contains are useful, but they uniformly show Jenner in the best light. What are we to make of Baron’s assessment: ‘Jenner stood in a position never before occupied by mortal man; having been the instrument in the hands of a gracious Providence, of influencing, in a most remarkable degree, the destinies of his species’?2 Jenner, for Baron, was sent by God himself.

Medical historians have long been familiar with the messy and contested reality of Jenner’s innovations and greatness, but there is no recent academic biography of his life in its entirety, even though much of Jenner’s correspondence survives. The latest biography, by Richard Fisher, is long out of print.3 Articles appear here and there on various aspects of Jenner’s life and world, but their reception is confined to small academic audiences. Common knowledge on Jenner’s life does not seem to run too deep. Considering the magnitude of Jenner’s contribution to medicine, it is perhaps surprising that he continues to be known as a kind of two-dimensional saint: a saviour of humanity with a statue here and there. This reputation in not confined to Britain; it stretches from Europe to the Americas, and from the Indian subcontinent to the Far East.

How does such a hero emerge? How can such an exceptional figure rise above the clamour and change the course of history? The answer is not a mystery, but hidden in plain sight. As a country surgeon, Jenner was not so extraordinary. His was a life of parochial interest, touched and pushed in various ways by exceptional circumstances, energetic friends and sponsors, and a deep-seated awareness of the importance of public reputation. Far from being set apart from the late eighteenth-century world of medicine, gentility and Enlightenment, Jenner was immersed in it. Tucked away in rural Gloucestershire, seemingly detached from the nature-conquering endeavours of urbane men of letters, Jenner was actually steeped in Enlightenment values, borne on a wave of correspondence and personal connections in London and farther afield. Setting up a country practice to meet his material needs, Jenner was motivated to experiment by a commonly held desire to understand nature so as to master it. With this firmly in view, the smallpox vaccination experiments can be put into a broad context of medical, anatomical and physiological experiments that Jenner carried out at home, some of which were successful, most not. The overwhelming success of vaccination would come to define the second half of Jenner’s life, but he had not planned for this. He spent his energy, with considerable chagrin, on the defence of his reputation and ended his life filled with uncertainty about his personal, professional and medical legacy.

The status of Jenner’s reputation at his death and in the decades that immediately followed should make us all the more amazed that we have come to know Jenner as a hero at all. He was hounded by anti-vaccinationists in his lifetime; the anti-vaccine movement throughout the nineteenth century made serial concerted attacks on Jenner’s character, his medical insight and his morality. Vaccination against smallpox would lead to riots, protests and paranoia. Vaccination was, for many, a scourge in itself, blighting children with animal or pestilential matter, and trespassing on the liberty of parents to decide what was best for their children. Anti-vaccination societies sprang up, particularly in Britain. Many prominent voices decried Jenner’s work as quackery, thrust upon an ignorant and vulnerable population by government tyranny, risking the health of the poor. Jenner’s allies, during his own lifetime and afterwards, fiercely defended the medical breakthrough that Jenner had made. Public opinion was polarised into Jenner-haters and Jenner-lovers. Those people who celebrated Jenner – usually prominent medical and scientific public figures – were forced to do so in unequivocal, absolutist terms, in the face of a torrent of abuse. Almost coeval with the invention of vaccination itself, therefore, arose the legend of Jenner the saviour of humanity, and the frightened naysayers of vaccination.

Edward Jenner was born in May 1749 in the village where he would come to spend most of his life, Berkeley in Gloucestershire. The son of the local vicar, Jenner was given a classical grounding for his education, first at Wotton-under-Edge and then at Cirencester. He was raised by his sisters after both of his parents died in 1754, when Edward was only 5 years old. He was probably fairly typical for a boy of his social class, making sport of the collection of nests (dormice were his special proclivity) and searching for fossils. At the age of about 14, a somewhat hypochondriacal Jenner was packed off to Sodbury near Bristol, where he became apprentice to Mr Ludlow, a local surgeon. There is little record of Jenner’s time spent learning the ropes of surgery, but he clearly became competent enough to attract the attention of the London elite. In 1770, a keen 21-year-old, Jenner moved to London to work under John Hunter, residing with his family for two years and, according to Baron, becoming his ‘favourite pupil’.4 Hunter at that time was surgeon at St George’s Hospital in Tooting, while also running a menagerie at Brompton for the purposes of scientific experimentation and observation. Hunter’s combined interests would soon become Jenner’s. There was love between the two men, in the manner of eighteenth-century relationships that were based on fellow feeling and frank exchange. But Jenner could not get on with London – he would come to have a deep resentment for it – and returned to take up his practice in Gloucestershire, dividing his time between Berkeley, his ancestral home, and Cheltenham. While Hunter may have allowed his pupil to leave, he would not leave him alone.

1

Going Cuckoo

But why think, why not try?

John Hunter, 17755

The popularity of natural historical observation in England reached a peak with the publication of Gilbert White’s The Natural History of Selborne in 1789. Jenner tapped into the popular mood, and assured himself a place of honour among scientific minds, by going cuckoo in 1788. In that year he finally published his ‘Observations on the Natural History of the Cuckoo’ in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, after more than a decade of thinking about it. The article capped years of ad hoc research in which Jenner observed, shot, collected, dissected and prepared. It is easy, perhaps, for the contemporary reader to see in Jenner’s rambling and scrambling among the hedgerows, looking for birds’ nests, a mark of amiable eccentricity. Yet Jenner was of a piece with many of his peers, who sought to explain the natural history of the phenomena around them by collecting, and often by killing, what they saw. Not only was his treatise accurate scientifically – it was the first to fully explain what happened to the ‘siblings’ of cuckoo chicks and why – it also tapped a rich vein of general interest.6 Jenner was a man of the moment.

The cuckoo research did not come out of nowhere. Jenner was Hunter’s country collector, doing experiments at his bidding and sending all manner of materials to London. Hunter wanted salmon, eels and cuckoos, and had an insatiable appetite for hedgehogs. Hunter once wrote to explain an experiment involving living bats, ‘if you catch any’.7 The ‘if’ was, undoubtedly, an imperative. Between them, they materially accelerated the disappearance of the bustard from England, its rareness even in the 1780s making Hunter all the more desirous of having one killed and sent. Jenner’s roaming of the countryside on his way to the homes of patients provided the ideal opportunity to fill his bags. His spoils went by the new mail coach service, which started in 1784 between Bristol and London, via Bath (and which must have exercised a high degree of tolerance with Jenner’s parcels). Mostly, Jenner’s preparations were already dead, but sometimes they were sent to Hunter alive. As early as 1773, Hunter commissioned Jenner to provide him observations on cuckoos and on the breeding of toads, congratulating him at the same time for his success with parsnips. Within days, Jenner sent him a cuckoo’s stomach by mail. Hunter demanded more, telling Jenner to start meddling with cuckoo eggs, placing them in different nests and keeping an account of his observations.

The research was anything but disciplined. Jenner, on his rounds, would stop to observe, shoot and collect. In his mid-twenties, Jenner was much more concerned with hedgehogs than with cuckoos, trying to find out (again at Hunter’s behest) what happened to their temperature at different times of year. Jenner’s work room at home must have been a forbidding place, as he beheaded and dissected one hedgehog after another; then cuckoos, rooks, swifts, martins, and later dogs, and the organs of cows, pigs, and, occasionally, people. Jenner was particularly interested in the sexual habits of various animals, and he carefully measured the size of the testes of many birds at different points in the season. Hunter set him about sexing eels.

Such enthusiasm for experimentation was not untypical for a young man of science, filled with Enlightenment principles. There were no ethical quandaries; only the pursuit of knowledge. This drive would come to be essential to the development of the vaccine, which employed children as Jenner’s experimental subjects. Jenner’s attitude towards the natural world was directed, shaped and commanded by Hunter. Any tendency to intellectual speculation was soon eliminated in favour of more practical methods. In a letter of 1775, Hunter made this perfectly clear: