Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

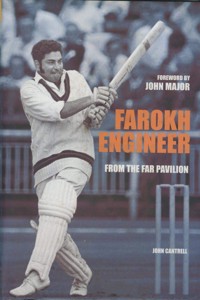

Born in Bombay in 1938, Farokh Engineer quickly displayed a prodigious talent with both bat and gloves. Selected to play for the India Starlets in the late 1950s, by 1967 he was signed with Lancashire. Farokh was instrumental in both the renaissance of the Red Rose County's fortunes and in the forging of the Indian team into one of the major forces in world cricket. With a foreword by John Major and highly illustrated, this is an essential read for any cricket fan.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2005

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

FAROKH ENGINEER

FROM THE FAR PAVILION

FAROKH ENGINEER

FROM THE FAR PAVILION

JOHN CANTRELL

In loving memory of my parents, Minnie and Manecksha, together with my brother Darius, to whom I owe everything, with deepest affection and gratitude.

Farokh Engineer

First published 2004 by Tempus Publishing Limited

Reprinted 2005

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© John Cantrell, 2005, 2013

The right of John Cantrell to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5253 8

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

1

Family Matters

2

Backstreets and Beaches

3

Starlet

4

International Cricket

5

Indian Domestic Cricket

6

Finest Hour

7

A Passage to England

8

The Red Rose

9

Lancashire, La La La

10

India’s Number One

11

Life after Cricket

12

Reflections

Farokh Engineer’s Dream Team for India

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Revd Malcolm Lorimer and Keith Hayhurst of Lancashire County Cricket Club, Ravindra Kumar, the Director and Managing Editor of The Statesman, The Rt Hon. John Major CH for writing the foreword, Mihir Bose for the invaluable information contained in his A History of Indian Cricket, John Bever for his meticulous proof reading and Julie and Sarah for their unflinching support and encouragement throughout this project. Wherever possible, memory has been checked against the record, for which purpose thanks are due to Wisden and CricInfo.

Foreword

Farokh Engineer is one of the great entertainers of cricket. Whether behind the stumps or with a bat in his hand, he commands both the attention and the enjoyment of his audience. He is the same off the field – buoyant and a bundle of fun, anxious to enjoy life to the full.

Farokh lives his life as if there is no tomorrow and as much as possible must therefore be crammed into today. Caution and ‘percentage’ batting are alien concepts to this buccaneer, although frustration with an injudicious shot that cuts short his batting is a familiar sensation to those who have followed his career.

As a wicketkeeper, Farokh is among the best I have ever seen: unconventional sometimes, but with astonishing reflexes as the impossible catch or stumping is made to seem commonplace.

Cricket is rich in characters – more so, I think, than in any other sport – and Farokh Engineer can take his proper place in the pantheon of them.

The Rt Hon. John Major CHSeptember 2002

Introduction

Farokh Engineer retired from professional cricket in 1976. In the quarter century or so since this event he has considered writing his memoirs or an autobiography on a number of occasions – indeed he often refers to a lost manuscript – but the completion of such a task has always eluded him as business affairs and family commitments have taken precedence. To date he is surely one of the few distinguished cricketers of his generation to have remained virtually silent in print. This is all the more surprising when one considers his swashbuckling and colourful personality, a past full of incident and a boyhood craze for reading the lives of great cricketers. My own friendship with Farokh is a recent affair, dating only from the beginning of 2001. We met at the Manchester Bridge Club. Halfway through an evening’s session, Farokh joined my table and introduced himself. It took a few seconds for the name to sink in but when the penny finally dropped I couldn’t help myself from remarking, ‘But you’re a famous cricketer’. Farokh later told me in jest that his confidence in my judgement was rooted in that moment. From that time onwards we began to play bridge together as partners (Farokh’s card playing was just as flamboyant, spontaneous and full of risk-taking as his batting) and I got round to asking him whether he had ever told his life story. It was a short step from this conversation to offering my services as biographer.

We would meet at regular intervals at his home, appropriately named ‘The Far Pavilion’ in Mere, Cheshire, where I was always given a warm welcome by his wife Julie, and daughters Roxanne and Scarlett. I would be armed with an antiquated reel-to-reel tape recorder and microphone while Farokh plied me with beers, curries and anecdotes. The results of those meetings form the backbone of this book. In a sense, what follows is a departure from the critical objectivity of conventional biography. This is not a ‘warts and all’ study. It is, rather, a belated celebration of Farokh’s life and cricketing achievements. Wherever possible I have let him tell the story in his own words, which are reproduced verbatim on the page. I have intervened to provide introductory sections and links between Farokh’s words and also to acknowledge his successes in a way that only an outsider can do if the subject’s modesty is to be preserved. My role has therefore been a combination of biographer, editor, advocate and admirer.

To seasoned cricket enthusiasts Farokh Engineer needs little introduction. But for the benefit of the very young, forgetful or unversed, a few summary words of assessment are perhaps appropriate. Sir Donald Bradman considered Farokh ‘one of the world’s great wicket-keeper batsmen’, and Sir Leonard Hutton’s verdict was that ‘he must certainly be classed as one of the best wicket keeper batsmen of all time’. Tom Graveney wrote:

Farokh ‘Rooky’ Engineer is one of the greatest wicket-keepers India has produced. He was acrobatic and had tremendously fast reflexes, getting to the ball and removing the bails in a flash if the batsman’s foot was raised. Farokh was also a top-flight batsman and served both India and Lancashire with distinction.

These twin talents enabled Farokh to play a key role in the transition of India from what might be considered a second division side, alongside New Zealand and Pakistan, to one of first-rank international status and an equally important part in the renaissance of Lancashire County Cricket after the lean years of the 1950s and 1960s. The former contribution was acknowledged by Don Mosey of the BBC:

Farokh Engineer has probably done more than any other player to promote Indian cricket to world class status – certainly he has done more than any player since the war, in a period when Indian cricket was emerging as something more than endurance-test batting and high-quality spin bowling.

Ray Illingworth wrote in similar vein when he claimed that ‘India’s emergence as a world class side probably owed more to Farokh than any member of the side, including their World Class spin bowlers’. When Farokh joined Lancashire in 1968 the county had not won a major honour since 1950. Eight years later they had won the Gillette Cup four times and the John Player League twice. But Farokh’s contribution to the game of cricket goes beyond his batting averages and work behind the stumps. He was one of the great characters of the game, infecting all with his good humour, selflessness and zest for life. Colin Cowdrey clearly recognised these qualities:

In all my cricket years, and I mean this most sincerely, I have not known anyone who has embodied the true spirit of cricket more completely than Farokh Engineer. He is the keenest and liveliest of cricketers.

Hot property.

The Pied Piper of Cricket.

The two-handed longsword.

John Arlott wrote: ‘His cricket is spontaneous; he plays it as he does because it is his nature to enjoy the game, and he sees no reason to conceal that enjoyment.’

Farokh was both an entertaining and exciting player, an instant hit with the young and an excellent ambassador for the game. Sometimes dubbed ‘the gay cavalier’ (his other nicknames included the ‘Persian Pirate’ and the ‘Pied Piper of Cricket’), his essential message was that cricket was to be played and enjoyed to the full. He has been compared by Eric Todd of The Guardian to a cricketing version of Don Quixote: ‘always looking for some new adventure, always prepared, so to say, to tilt at windmills whenever he opens the batting.’ Derek Hodgson of the Daily Express noted that while Farokh ‘could drive with the best’, he could also ‘use his bat like a two-handed longsword’. It was this unpredictable, exuberant and vital approach to almost everything Farokh attempted in cricket that made him such a favourite with the crowds. There was, of course, a reverse side to these talents, for if Farokh could dazzle and inspire with breathtaking shots, he could also frustrate and dismay, sometimes losing his wicket to reckless and impatient strokes. Yet, as Neville Cardus once remarked, it is almost impossible to combine brilliance with consistency. Farokh was a cricketing meteor, a shooting star, sparkling, refreshing and exotic. At times his tenure of the crease was tantalisingly short but some would argue that this was the price of his genius.

Farokh Engineer remains a popular figure, especially in India where he is still recognised and mobbed on the streets. He receives about half a dozen postal requests for autographs each week and was recently nominated amongst the top 100 of the best-looking Asian males of the twentieth century by Indiatimes. In England he is regularly invited to sporting functions, to after-dinner speaking engagements and other events ranging from the judging of beauty contests to fund-raising ventures for underprivileged and terminally ill children. His cricketing reputation has undoubtedly assisted his business activities which, in turn, have enabled him to live comfortably amongst the sporting élite of north Cheshire. Farokh’s philosophy ‘always to go for it’ has ensured that if he ever failed to achieve an objective it was not for the want of trying. His life is one of attacking enthusiasm, of saying yes rather than no and preferring to take a chance than opt for safe and pedestrian ways. At the age of sixty-five he is still a bundle of energy, still working to improve his business affairs, still encouraging and provoking the young. This is the tale of a man who looks forward to the future as much as he reflects on the past.

Well positioned at fine leg.

Sometimes compared to Englebert Humperdinck – but only with his mouth shut.

one

Family Matters

Farokh Engineer is from India, yet his surname is decidedly English. Despite an educated middle-class background and a natural curiosity about the world, he knows little about his immediate forebears. Yet it seems likely that sometime in the nineteenth century his great-great-grandfather was employed in the newly formed engineering industry, perhaps working on the railways or in the dockyards or government-controlled powder mills. Hence, like many of the English, Farokh sports an occupationally-related surname. Farokh is a name of Persian extraction meaning joy or brightness. Significantly it was at the moment when the lights were turned on for the evening in the Bombay hospital of Farokh’s birth that he first entered the world. If Farokh’s immediate past is shrouded in uncertainty, the history of his more distant ancestors is much clearer. For Farokh is a Parsee and the Parsees were originally from Persia, the modern-day Iran. Moslem persecution between the eighth and tenth centuries forced them to leave their homeland, still nursing the flames from their sacred fire, and seek refuge abroad in sail boats. Many found sanctuary in western India, especially around Bombay. The local ruler allowed them to maintain their own customs and traditions such that they always retained a sense of separateness from the indigenous population – ‘the Jews of India’, as they have sometimes been called. When India was colonised by the British the Parsees proved willing collaborators and even today a large number of Parsee households are adorned with portraits of the royal family. Many Parsees became traders, businessmen and members of the professions.

Dreaming of Test cricket.

When Farokh was born on 25 February 1938 India was still a British colony, although various concessions had been made to self-government. One of the most obvious signs of India’s colonial status was the prevalence of cricket throughout the subcontinent. In one sense the game was a symbol of British rule, yet the Indian population was always able to distinguish between the intrinsic merits of the game and those who had introduced it to their country. Playing cricket was not regarded as a demonstration of support for the Raj or a symbol of the white man’s domination. The Engineer family was typical of many Indian families who watched or played cricket because it combined intelligence with skill, fitness and athleticism and provided gladiatorial encounters without bloodshed. It was an essentially civilized sport, sometimes demanding great patience, in which fate also played a significant role with what could be decisive tosses of the coin and changing pitch and weather conditions. It naturally appealed to a gentle, civilized people who had not always been able to control their own destiny.

Minnie and Manecksha.

During his early years Farokh enjoyed the security of a thoroughly supportive family, the immediate core of which was his father, mother and older brother. These three key figures were the most important formative influences on the new arrival in the family. Farokh’s father Manecksha was a medical doctor – Dr Engineer, as he liked to joke. He worked as a general practitioner for TATA, the giant industrial conglomerate which had fingers in virtually every pie from airlines to chemicals and paper manufacture. In 1938 he was based in Bombay and living in Dadar, a prosperous suburb which has been compared to Pudsey in Yorkshire – but only in regard to the number of Test cricketers it has produced (Tamhane, Gupte, Desai, Gavaskar and Tendulkar all grew up in or close to Dadar). Shortly afterwards Dr Engineer was posted to Bhivpuri, a pretty village settlement in the mountains some 100 miles from Bombay where TATA were building a dam to service the needs of a power station. The village was surrounded by thick jungle where maneaters – leopards, panthers and tigers – and other dangerous beasts, including elephants, would prowl and claim the occasional life or limb of a hapless villager or part of their herd of cattle. On such occasions Dr Engineer would be summoned, for he was the only local equipped with a rifle. If the young Farokh went with him on these dangerous missions he would be told to climb up the tallest tree ‘and not breathe a word’ until the threat was seen off or killed. Dr Engineer was a tall, bespectacled, well-built man, respected and admired by all who knew him but especially by his youngest son:

He was an extremely mild-mannered, extremely polite person. In fact, I’ve never – and I mean that, never – seen my dad lose his temper. He never said one wrong word about anyone and he was just too good to be true. He was a marvellous doctor; people that didn’t even know him used to ring him in the middle of the night and he used to take his medical kit and go. If ever there was an honour I think my dad should have got it because he really served the community and we were in a village where there were no doctors at all for hundreds of miles, literally. Dad had to perform the trickiest operations because he was the only one with medical knowledge and saved so many lives there – people were bitten by poisonous snakes and all sorts. Operations, he had to do them – it was him or the butcher, and my dad had to perform these operations or the people would have died. He was a voracious reader; he was up to date with medical books all the time. He was an extremely intelligent person and he just loved sport: he was a very good tennis player and a very good cricketer, at club standard. He had a very dry sense of humour, not too blasé, a very soft-spoken, mild-mannered man. Gosh, I’m extremely the opposite!

Many of the stories about Manecksha Engineer reveal a man equally devoted to his son, a man willing to sacrifice, foster and encourage in every conceivable way in order to promote the skills of an emerging talent:

He was an opening bowler and used to be pretty useful with a new ball. He used to come and bowl to me sometimes. He started off bowling slowly but gradually got faster as I started hitting him to all corners of the ground. Sometimes, when there was no-one to practise with, Dad used to come and bowl to me and (there were no fielders) I used to hit the ball over his head or wherever and, poor chap, he used to run miles and get it and bowl the next ball and I used to hit it again. Now I feel so bad making dad do all the running, but he just wanted me to be a good player.

Farokh’s mother, Minnie.

Manecksha sometimes found it impossible to conceal his pride and interest, even at the risk of earning a filial rebuke:

My Dad used to love coming to watch me play and I used to feel extremely embarrassed because no-one else’s father would come to watch. I used to plead with him, ‘Please don’t come, I can’t concentrate,’ and he promised that he wouldn’t come. But he was so, so keen and I never forget one day it was raining, it was an ordinary club match and we carried on playing in the light drizzle. Someone mentioned, ‘Farokh, your father is getting wet.’ He was standing under a tree, virtually hiding. ‘Please ask him to come and sit in the pavilion, we would love to welcome him there.’ That’s when I realised my Dad was there and when that person told me I felt so bad and I signalled to my Dad and he was so pleased.

In contrast to the rather quiet, easygoing and unassuming father, Farokh’s mother, Minnie, had something of the extrovert about her. The daughter of a doctor, she too was a keen sportswoman, an excellent tennis player and an avid follower of her son’s cricketing successes – but via the radio commentaries. When Farokh arrived home after a game she would ask him, ‘Why did you get out to that ball?’ It was always a source of regret to Farokh that she never lived to see him become famous in terms of making an impact in international cricket. Farokh describes her as ‘a great lady’ and adds that he ‘still worships her and thinks of her every day’. In addition to sport, Minnie played the piano and violin and Farokh describes her as ‘culturally refined’. Indeed she came from a musical family which included the conductor Zubin Mehta, who held appointments as Musical Director of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra and Bavarian State Opera Orchestra. He is popularly associated with the Three Tenors and conducted their concerts in Rome and Los Angeles. Zubin used to come and watch Farokh play Test cricket:

He used to be in the player’s enclosure as my guest and these young kids came running up to me for autographs and I’m signing away merrily there. One little lad asked for Zubin’s autograph and Zubin said, ‘Why do you want my autograph?’ ‘Because you are Farokh Engineer’s cousin,’ came the reply. Over the years Zubin and I have had a chuckle over this and he often used to tease me by asking, ‘And how’s my famous cousin?’

Minnie’s sense of natural justice, even embracing the animal kingdom, is illustrated by the story of the cobra, an event which took place when Farokh was about three or four years of age:

Mum used to place me on the lawn with my toys while she used to do her work. She left me for just a few minutes but when she got back a huge cobra was right by my side and he was shaking his neck one way and the other and I was virtually playing with him shaking my own neck from side to side. It seemed as if he was copying me! These are the most venomous killers, but he must have seen me as a child and not going to do him any harm. As soon as my Mum and the servants saw what was happening they panicked because the cobra was within striking distance of me, about a foot. But all of a sudden, the cobra put his head down, turned round and very slowly moved towards the tall grass. The servants ran out with sticks to try and kill him but my Mum stopped them. She said, ‘Don’t hurt him, he hasn’t hurt my son.’

Mother and son.

Minnie was as keen as Manecksha that the young Farokh should excel at his sport, but she was determined that his academic studies should not suffer. Lessons and homework had to take precedence over cricket practice, and the diminutive Minnie would climb onto a chair so that she could wedge a stopper between the door and the door frame to prevent her son from escaping. The stopper would only be removed when the schoolwork was complete. There was one occasion on the eve of a set of examinations when the secretary of the local cricket club, keenly aware of the matriarchal house rules, crept up to the Engineer family home in order to persuade Farokh to play in an important game. Minnie had gone out, so thinking that he could complete his revision in the evening, Farokh collected his bat, pads and gloves and set off for the match:

I was batting and scoring runs when I saw my mum walk onto the pitch and march all the way to where I was standing. ‘You… Out,’ she shouted, ‘You’re coming home now, you haven’t done your lessons.’ And she took me off the field in the middle of a club game telling off the other players: ‘Would you allow your sons to play a cricket match the day before his exams? He has all the time in the world afterwards but he has to pass his exam.’ I was so annoyed with her and so embarrassed but eventually I passed my exam and had to thank her for it.

Minnie was health conscious, keeping buffalo for milk instead of cows. From a medical family and married to a doctor, Minnie had little time for high-tech medicine and relied instead on home-spun remedies:

Mum was a great believer in honey, pure honey. We used to get our servants to collect pure honey from the mountains and whenever myself or my brother was ill, or anyone else, mum gave us a teaspoon of honey. And Dad was suggesting antibiotics and all sorts of things but she said, ‘leave all that rubbish alone, just have my honey and you will be all right,’ and by golly she was right. Honey never did us any harm and we were as right as rain the next day.

Minnie’s whole life was devoted to the welfare of her children. This was even apparent at meal times:

When we had a roast or lobster or whatever my brother Darius used to have the best piece and I used to have the second best piece. If we had a fish, for example, Darius used to have the best, I the second best, Dad used to have the third best and Mum would finish with the head, literally. Not literally the head, but near. She was a very self-sacrificing lady and she enjoyed doing that because she just wanted the best for her children.

Although assisted by servants, Minnie did most of the cooking and the shopping. Young Farokh would often accompany her to the fish market:

She used to press the fish in the right spot to find if the fish was fresh or not. Those things were taken for granted in the fish markets of Bombay. You can’t go into Marks & Spencer today and start squeezing the fish; that wouldn’t make you very popular.

But despite Minnie’s insistence on natural remedies, a good wholesome diet (avoiding chillies and vinegar) and physical fitness, she died relatively young and quite suddenly in her early fifties. Farokh was some 500 miles away from Bombay playing cricket at Jamnagar when Minnie was taken into hospital:

I got a message that my Mum had been taken ill and would I return home. My family had never interrupted me from a cricket match before so I knew that something was very, very serious. The last flight to Bombay was at 3 p.m. and it was already 3.15 p.m. by the time I got the message. The nearest airport was at a place called Ahmedabad 300 miles drive away. Jamnagar was a state run by a Maharaja; they were all very keen on cricket, cricketers stayed at their palaces and were entertained lavishly. He gave a load of rupees to his old driver who drove a huge Cadillac, left-hand drive and one of the old models. The Maharaja said, ‘Just take Farokh to Bombay or to Ahmedabad and try to catch the plane. I will phone Indian Airlines to see if they will hold onto the plane.’ This driver drove the car at 30mph on the dirt-track roads. I calculated the time very quickly and realised that we wouldn’t reach anywhere in six hours at this speed. So I told the driver to come into my seat and I took the controls. I had never driven a left-hand drive car in my life before and I was tearing, I must have been going at about 100mph to catch that flight and we were about half an hour late. Indian Airlines had held onto the plane but the flight was full and passengers were told that Farokh Engineer’s mother was ill and Farokh needed a seat on the plane (I was just beginning to gain a reputation at this stage). Would you believe that each and every passenger said I could have their seat and in the end the captain said, ‘There is no need for that. He can come in the jump seat.’The captain told me about this during the flight and I went out and thanked everyone over the speaker system. Anyway I landed and dashed to the hospital, arriving between eight and ten o’clock in the evening. I was at Mum’s bedside all through the night with tears streaming down my face because I knew she was dying and the doctors had said she was fading away. Suddenly my Mum put her hand on my head and said, ‘Don’t cry son, I promise I will come back to you as your first daughter.’Those were the only words she spoke to me and with her hand on my head she passed away. And I knew that my first child was going to be a girl.

The cause of Minnie’s death was never established and she died while under medical observation. Her husband lived another twenty years on his own, surviving cancer of the throat, until he succumbed to old age in his early nineties.

Minnie and Manecksha were both Parsees and they made sure that their sons were brought up in a way that was consistent with the values of the Parsee religion:

The Parsee religion was not particularly strict, there was nothing rigid saying that you must do this or must not do that. It is said that the Hindus refuse to eat beef while the Moslems refuse pork. The Parsees, however, like their meat medium rare. It was a very simple, very easy religion which stressed three things: good thoughts, good words and good deeds. But I think most religions will tell you that. From time to time we would visit the Fire Temple where the flame is never allowed to go out. It was transported across the Arabian Sea from Persia centuries ago; every fire temple in the world burns a flame from this same source. Outside the temple we would buy some sandalwood to put on the fire, creating a sweet-smelling fragrance. My parents never insisted that I go to the temple. They said their prayers at home and tried to promote the virtues of life. We were brought up in a good way. We were not a very religious community though we believed in God and I still say my prayers every night before going to bed, thanking my parents and my prophet Zarathustra for all they have done for me.

The Parsees lived in a very westernised way and came into close contact with the British, imitating many of their customs and traditions, such as a good English breakfast with bacon, eggs and mushrooms. In fact, just about everything except black pudding! We would celebrate Christmas, Diwali [the Hindu New Year], Id [the Moslem New Year] and Nowroz, the Parsee New Year, exchanging cards and presents. On the whole the Parsees were an affluent community, including top industrialists such as the Tata family, top lawyers, surgeons and educationalists. They built hospitals, schools and libraries and generally did a lot for the Indian community. Of course, because they were successful there was some jealousy and fun would be poked at the old-fashioned Parsee in just about every Indian movie; there he would be with certain exaggerated mannerisms which even I would laugh at. My only criticism of the religion is that it is too exclusive. Other religions try to spread their gospel and recruit new members, but not so the Parsees. Even my wife Julie, who is English, is prevented from becoming a Parsee because she wasn’t born one. It is exceedingly snobbish and, regrettably, a dying religion because no new members are admitted. The leading elders could surely take steps to make people more aware of this beautiful religion and change certain principles especially with regard to the membership.

One of my strongest memories concerning the religion involves birthdays and weddings. On birthdays we used to dress up in new white shirts and shorts or trousers before visiting the Fire Temple, while for weddings there would be a feast with the tastiest food in the world. The celebrations would include a ‘nankhatai’ band which nearly always played out of tune, but with great gusto, and the food would be served on banana leaves. It was fantastic. There was nothing to beat that banquet.

The third pivotal figure in Farokh’s childhood was his brother Darius, five and a half years his senior. Darius was also a keen sportsman and according to Farokh ‘was a far better cricketer than I ever was but he never played Test cricket’. The reason for this was apparently ‘politics in Indian cricket’ for he was ‘a brilliant off-spinner and attacking batsman’. It was Darius who encouraged his younger brother to take up wicketkeeping:

He was a terrific off-spinner and could turn the ball square on any track. For the club side wicketkeepers, leg-side ball-gathering was something unheard of then. Every time the ball turned it was just four byes. Darius used to get frustrated and one day the regular wicketkeeper was absent and the only way I could get in the team was by keeping wicket to take his place. My brother came on to bowl his off spin and not only was I taking the balls down leg side but I had a couple of leg-side stumpings which was completely unheard of. Leg-side stumpings! How can you stump a batsman when you are blind, it’s pure anticipation. And that’s what Darius said. ‘Gee you should take up wicketkeeping, you’d be absolutely brilliant, you’re the best wicketkeeper I’ve enjoyed bowling to.’ Every time we played he insisted that I was the wicketkeeper. And that’s how I really got started.

It was also Darius who introduced the young Farokh to the Brabourne Stadium, the scene of so much of his future cricket action with the CCI (the Cricket Club of India and the Indian equivalent of the MCC), with Mumbai and with India. The stadium was built on a piece of land reclaimed from the sea and presented to the CCI by Lord Brabourne, the Governor of Bombay, after he was tempted with the offer of immortality. It was a stadium of contrasts between the luxury of the three-storey stucco pavilion and the segregated wire-caged compounds providing the cheapest seats:

Brother Darius.

My brother would take me on his shoulders, otherwise I would have been trampled by the crowds in the East Stand. This East Stand made the Stretford End at Old Trafford look like Buckingham Palace. There was only concrete flooring with no seats and you had to stand on this concrete packed like sardines – sardines were much more comfortable in their tins than we were. And we would be over each other’s heads and shoulders and everything and I virtually saw an entire international game perched on my brother’s shoulders because it was the only way I could see. I remember Darius taking me to the front row and who should I see having a chewing gum but Denis Compton – he lived in India for a number of years during the war. He was fielding on the boundary line and I must have said, sitting on my brother’s shoulders, ‘Hello Mr Compton’ or ‘Hello Denis’. And he just opened a packet of chewing gum and asked if I would like one but I was too nervous to say yes and he just flicked me one, he tossed me one and I caught it. Boy, I didn’t eat that chewing gum for years, I think I just kept it and I told Compo about this in later years when we became really good chums in England.

Darius went to England to study structural engineering and design at Imperial College, London. He then began practicing as a structural engineer based in London, but moved to Bowdon, Cheshire, when Farokh began playing for Lancashire. He found it irksome and time-consuming explaining to incredulous customers that both his profession and name were ‘Engineer’, so he changed his name to Shaw, his father’s middle name. Sadly, Darius died in 1997. His name lives on with the Darius Shaw award presented by Farokh each year to the most promising youngster at Mobberley Cricket Club in Cheshire.

In addition to Darius there were also Dossy and Pervin. Minnie was Manecksha’s second wife and Dossy and Pervin were the children of the first marriage. Farokh was always a little scared of Dossy for he was ‘pretty strict’, but he still enjoyed his company because Dossy was a mechanic and used to take his half-brother under cars with him while he performed repairs. Better still, Dossy had a motorcycle. Farokh remembers making unauthorised use of this machine on one occasion while his brother was at work. The escapade was originally intended to be a single circuit of the home around the perimeter paving, but this escalated into at least fifteen rounds and then straight out onto the streets to show off to the girls. When Dossy returned he noticed that his motorcycle engine was warm and guessed at what Farokh had been doing but ‘didn’t seem to mind too much’. Pervin was a God-fearing lady and ‘a holy type of person into meditation and all sorts of things’. She lived with her husband, Dhun, in Madras, and Farokh used to take vacations at their home, named ‘Cosy Nook’. Here he would sleep on the balcony overlooking the sea. Like Dossy, Dhun also had a motorcycle, which was an obvious attraction for the thrill-seeking Farokh; he even managed to crash it on one occasion.

Other family members make but fleeting appearances in Farokh’s recollections of his early years though he has vivid memories of visits to his maternal grandmother who lived in a sixth-floor apartment in Bombay. Farokh remembers sitting on the balcony and throwing ice cubes onto the people below. Such naughtiness would have severely displeased the only other relative to have made a lasting impact, Aunt Nergish, his father’s elder sister. This formidable lady was a headmistress and described by Farokh as both ‘a very boisterous old lady’ and a ‘tyrant’. Her tyranny was primarily exercised on birthdays:

I used to dread my birthdays because when it was my birthday one of the things we had to do was to go and see Nergish aunty and every year I got a bloody pyjama as a birthday present. I never wore pyjamas, I used to always sleep in shorts. She knew I hated bloody pyjamas. And that dreaded kiss. When she used to give us a kiss it was like injections, her lips used to go and scoop up half a gallon of your blood and my brother and I used to dread that kiss from Nergish aunty.

But this was a very minor inconvenience in an otherwise happy childhood. His parents’ marriage was undoubtedly successful, with Minnie taking obvious pride in her husband’s achievements. Farokh describes the family as ‘closely knit and loving’ and it clearly provided him with emotional security, a joy of life and the encouragement to pursue his interest in sport to the highest level. Few can demand more of their parents.

two

Backstreets and Beaches