9,34 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Upstart

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

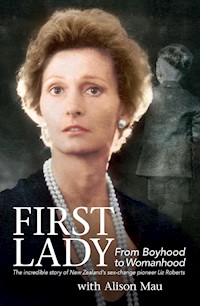

Liz Roberts is a Kiwi pioneer; the first person to undergo a full surgical sex change in New Zealand. This inspirational memoir tells the story of how, with the help of medical specialists working in previously uncharted territory, she changed her name, her sex and her legal status in the 1970s, freeing her to live a new life as a woman. The little boy born Gary Roberts in 1950s Christchurch knew from his earliest years that he was different to the other boys. Gary overcame a violent childhood to train first as a florist, then a hairdresser. He moved to England and his talent as a couture clothing designer was spotted and encouraged. He released his own collection, which made headlines back in New Zealand. He also became sure that a permanent change of sexual identity was a real possibility and began treatment. It was Liz Roberts who returned to New Zealand. Ground-breaking surgery, two marriages, and much heartbreak punctuated Liz's official transition from man to woman. Today, she still works as a designer and bespoke dressmaker. Her choices have made her enemies and admirers across the country, but few would doubt her strength and grace in tackling one of the most taboo life changes of all.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand

ISBN 978-1-927262-49-8

An Upstart Press Book

Published in 2015 by Upstart Press Ltd

B3, 72 Apollo Drive, Rosedale

Auckland, New Zealand

Text © Alison Mau and Elizabeth Roberts 2015

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Design and format © Upstart Press Ltd 2015

www.upstartpress.co.nz

First Lady is a true story, however for legal reasons, some names and places have been changed.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form.

E-book produced by CVD Limited

Dedicated to those contemplating my choice of life.

Contents

Imprint

Dedication

Contents

Writer’s Note

Foreword

Prologue

1. Childhood: being different

2. Boys’ home

3. Hairdressing

4. Lyttelton: hairdressing and dressmaking

Picture Section 1

5. Working on the ferries

6. Importuning leads to prison

7. Slow boat to London

8. London drag scene

9. The whirl of the fashion world

10. Leaving London

11. Tim, Round ONe

12. Tim, Round Two

13. Backstage in broadcasting

Picture Section 2

14. Surgery, 1969: the operation

15. Women’s prison

16. Further surgery, 1970s–90s

17. The lies people tell

18. Working in theatre

Picture Section 3

19. Weight and its problems

20. The legal battle

21. A medicated life

22. Friends, I’ve had a few

23. The traitor

24. My dogs

25. Mum and Dad

Epilogue

About the Writer

WRITER’S NOTE

On 6 June 2012, I appeared on TVNZ’s Close Up in a debate with Baptist theologian Laurie Guy, on the subject of same-sex marriage. It had been barely a month since US president Barack Obama had endorsed the idea, and New Zealand’s John Key had quickly followed by saying he was not personally opposed to marriage between partners of the same gender. I told host Mark Sainsbury that with 63 per cent of New Zealanders now in favour of a law change, it appeared the tide was turning and the Church would lose the battle. Laurie Guy agreed.

A day later, at my desk in the Fair Go office, I took a call from a stranger. ‘I’m Elizabeth Roberts,’ she said, ‘and I wanted to congratulate you on the way you made your point without losing your cool last night.’ My first impression was of a beautifully spoken woman, a little ‘old school’, and very ladylike. She told me a bit about her life, and after half an hour or so of chat I had to stop her: ‘Elizabeth. Has anyone ever written your book? I’ll write it!’ (Apparently someone had once attempted to do so, but the result was such a sanitised version of events that Liz had thrown it in the bin.)

Although I began my journalism career writing for newspapers 30 years ago and continue to write occasionally for print to this day, I had never had a book published or even attempted to write one. It was a very rash promise to make. The fact that it has taken three years from our first conversation to this point is proof of what a novice I was when we began.

However, Liz’s story had to be told. Although she had no way of knowing it at the time, Liz was breaking legal and ethical ground in an era when just wearing a woman’s dress could get a man thrown in jail. And not just in New Zealand; Liz was the first in the Commonwealth to be issued a change of gender on her birth certificate. She had to convince GPs, surgeons, psychiatrists and bureaucrats to do things they’d never attempted or considered; and she succeeded through sheer force of will.

When Liz and I began this book, the human rights discourse was focused on same-sex marriage; in the years since it has shifted and transgender issues are somewhat of a hot topic. I hope this book will add a vital personal perspective to the conversation.

Although Liz’s life story is an important one legally and historically, it is really, at its heart, simply a bloody good yarn. And Liz is a good woman. I’m honoured to have been able to bring my friend’s story to you.

Alison Mau

Auckland 2015

FOREWORD

On a warm Auckland Sunday in January 2013, I sat in the lounge of a 1930s style state house with two extraordinary women. One was dressed in a house frock with curlers in her hair, the other in jeans and blouse with the confident air of a professional journalist. We sat together and watched an old VHS recording of Paul Holmes and the story of a transsexual woman who wanted to get married but who was refused permission to have a change of gender on her birth certificate. As the television story unfolded, Ali Mau leaned over to Liz Roberts and whispered, ‘You are so beautiful.’

Ali was there on one of her many visits in preparing for the creation of this book. I was there to gather research for my master’s thesis, which considered transgender representation in theatre.

I never knew Garry, but Liz is an old friend. Over the years she has designed and created hundreds of costumes for me from every imaginable period, and for uncountable themes, treatments and concepts. Every single costume was a visual treat, usually with some clever and surprising element, and often with a witty self-reference or a tongue-in-cheek in-joke. There was the piupiu made from beads and drinking straws for Oberon, King of the Fairies, in a Maori interpretation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream; the leather-kilted Macbeth who rode a Harley and sold drugs; or the bejewelled codpiece for shocking-pink Horatio in Jean Bett’s Ophelia Thinks Harder.

Liz’s wicked sense of humour has been captured beautifully in this book. Despite the hurts, the letdowns, the nastiness that has sometimes followed her, she has always managed to brush it off with an infectious wisecrack or stinging riposte, followed by gales of laughter.

Ali Mau’s keen journalist’s voice is strong here. Her sensitivity, and ability to ask the right questions, provides a framework for an honest yet gripping yarn about one of our modern-day pioneers. This is, I think, an important book: one that records the very human story of someone who had the temerity to simply be themself. I love this book, as I love Liz, and Ali for her tenacity and talent.

Robert Gilbert

Christchurch, May 2015

Robert Gilbert has a Master of Arts degree with First Class Honours from Massey University. He is the author of a new play about transgenderism, called Trans Tasmin, and he is the Director of Theatre Arts at Rangi Ruru Girl’s School.

PROLOGUE

Dear Reader,

Just before you venture into the story of my life, I want you to know one thing.

This story, my excursion through life, has not been written with the intention of venting any anger I might hold towards my father. Sadly, ours was a fraught father–son/daughter relationship, which included many very difficult times and a mixture of emotions for us both.

I had to do what was right for me — what felt right for me, from the time I was very small — in order to survive. My father had his demons, and his own views on my choices, but I certainly have no regrets about the way I’ve chosen to live.

Close to the time my dad passed away he shared with me many things about his life, and he had softened there, at the end. This resulted in a much deeper understanding of each other; it would have made my dear mother very happy had she lived to see it.

And perhaps if this story had taken place now, in a world so changed from the one in which I grew up, our story could have been a very different one.

Liz Roberts

1 CHILDHOOD: BEING DIFFERENT

June 1947, a Christchurch suburb on a very special occasion; my kindergarten fancy-dress party. I was four years old.

Picture the scene: Grandma dabbing at her eyes with a lacework handkerchief, Granddad and my father Alex fussing with the complexities of the camera, Mum doing her best to coax me into the frame for the picture that would capture a treasured childhood moment. Or so they thought.

The little girl who lived next door, Carol, and I were to go to the party as Cinderella and Prince Charming. I knew what a fairytale couple was supposed to look like even at the age of four, but this one, on this day, was making me angry.

Grandma had made both costumes herself, silver stars and lace and a gorgeous blue for Cinderella’s dress, a crown, all the bits. They were absolutely beautiful creations, but I don’t remember what Prince Charming’s outfit looked like. Who cared about him? I wanted to go as Cinderella.

The adults soon twigged that something was amiss, as they tried to take the photo and I slid down the wall out of shot again and again. I couldn’t explain it, the grown-ups were furious, but I didn’t want to be Prince Charming. I wanted to be wearing that bloody blue dress!

I recall Grandma looked at Mum: ‘Don’t worry Eileen, he’s alright, Garry’s just different.’

It’s the first time I remember being called that. Different. I never thought of it that way, never thought I was unusual. It was just the way I’d always been. I never saw anyone like me, though.

There’s a photo of me from my early childhood that sums things up nicely. It shows a leafy Christchurch street and well-dressed family walking together, obviously off to some special occasion. The group has yet to notice that one of them is not playing along; the smartly suited little boy (me) has turned his back and is about to head off in the other direction. I remember the moment and the reason I’d decided to throw a paddy: we were going to my Auntie Barb’s wedding, and I had noticed that all the ladies were carrying handbags. I wanted one, too. Mother refused to hand hers over; I refused to go on without it.

Nana was onto me. I think they might all have been. I think mothers just know, don’t they? Whether it was dressing up, playing with ‘girls’ toys or making pretty things from scraps, she would say, ‘Don’t let your father see you doing that.’

She didn’t exactly encourage it, whatever the ‘different’ behaviour was on any particular day, but she protected me in the way she felt she could. When I think back with wiser eyes, I realise she was always covering for me.

When I was about fourteen and at the Boys’ Training Centre, I got a letter from her. It said I had to stop making the paper marionette puppets I loved to create, because my father wouldn’t approve. I had to grow up and be a man.

At primary school I wasn’t shunned or bullied, but I certainly wasn’t ‘one of the boys’ in the usual sense. I had friends for sure, and they accepted me as one of their mates. But while they were racing around my parents’ backyard playing Cowboys and Indians, I’d be busy preparing them a play ‘picnic’, laying down the blanket on the grass and plumping up the cushions, making sure the Cowboys had a comfy place to sit and a meal when they’d come home from the range. I was very happy with that role; it felt nice to have been able to find my useful place among the boys.

Nobody ever said a thing.

When I was seven my father took me to the theatre in Christchurch, to see The Tommy Trinder Show. This was a big occasion and a bit of a departure, as although my father enjoyed the arts, he was dead against encouraging any interest in the theatre, or anything ‘arty’ in me.

Trinder was a performer from England and although his was more a comedy show than a glamour drag act, he did several musical numbers and at one stage came on stage dressed as Carmen Miranda, with a huge fruit headdress. Later in the show it was as another famous temptress, Mae West. I sat, completely fascinated, but I don’t think I realised he was in drag. In fact, I wouldn’t have known then what it was. Dad seemed a bit dark after we left the theatre and when we got home, I said to Mum, ‘Why didn’t that man have any hair on his legs?’ She seemed flustered, and said, ‘Forget about that, it’s just powder, he puts powder on them.’

And I thought, ‘Ooooh, there’s an idea.’

At that point, just seven years old, I was curious. But perhaps something was taking shape in my mind, without me even realising it.

There were other signs.

My little sister Faye loved fudge, but she wasn’t allowed to eat it, so when our parents were out we’d shake hands on a secret deal. Into the kitchen Faye would go, collecting ingredients to make a glorious mess with the fudge recipe, and I’d do the same at the dressing table with Mum’s make-up. We swore each other to secrecy; both doing something we were absolutely forbidden to do.

I got caught a few times, of course, as a little boy couldn’t push at the boundaries of ‘normal’ behaviour without ever being sprung. When I was about eight I had a pair of school sandals, standard issue black leather, that I thought sorely needed an upgrade. I cut the straps off and painted them white, and was very pleased with the improvement. That morning I got as far as the gate before my father saw me and flew into a rage.

‘Look at that f***ing boy out there with those white shoes on.’

This wasn’t unusual, and it wasn’t the first occasion by a long shot. Around the same time I enraged him by wearing my winter coat cinched tightly at the waist with a belt, as I had seen the glamorous Hollywood stars (female, of course) do in the movies. I remember dancing down the street, pretending to be in one of those fabulous musical films. Once again, there was trouble.

By the time I was able to calculate, I knew my father had hated me from the moment I was born. It wasn’t at all hard to work out — I was always covered in bruises, always copped the blame, got very good at ducking out of the reach of his fists. The ‘why’ of it was always a puzzle for me, though. He certainly didn’t seem to feel the same way about the rest of the family. He did not hit my mother. My sister rarely had to see his rage.

It was only decades later I found out why he might have felt that way. He and my mother had lived within a street of each other growing up in quiet, Depression-era Christchurch; they met at school, and were the only partners each had ever had.

During the war he’d been in the air force and served in the Pacific. Family legend was that he’d been evac’ed out and sent back to New Zealand, injured, after a bomb fell on his foot. The truth — which wouldn’t come out for many, many years — was that on a visit home he’d got my mother pregnant. Any airman who found himself in that position had precious few choices — they were forced to marry the girl. He didn’t want to, but he did it. That baby was the reason his life had suddenly been yanked in a completely unexpected direction. You can imagine how that might affect an angry young man. For the rest of his life, if anything went wrong, it was my fault.

The circumstances of the marriage were always kept secret from Faye and me, even when we were older. Year after year we’d ask to put on a party, or a dinner, to celebrate their wedding anniversary, but we were always waved away. Mum would just say, ‘Oh, I can’t remember when it was.’ The truth came out just before my father died, when a cousin told us Mum had been pregnant with me at the time the wedding took place. By that time we were adults in our forties, and it was too late to have made any difference at all. Faye and I kept our mouths shut, and both Mum and Dad died with their secret intact.

It may not have changed anything, but it answered a lot of questions for me. I thought, well, now I know why.

Dad was brutal — there’s no other word for it. Never to Mum, just to me. He’d call me ‘the Bastard’ and no matter how many times my mum and my grandparents objected, I was a bastard to him, and I paid the price.

For the first few years of my life we lived with my maternal grandparents at their house in Glasgow Street, Linwood, and while we were there it wasn’t too bad — I don’t think he’d have laid a hand on me there. Perhaps he was too afraid.

My grandparents were lovely, lovely people. My grandma, mum’s mother, was a ‘court dressmaker’, that’s what they called couture seamstresses, and created high fashion for wealthy Christchurch ladies. She was hugely talented and much in demand. She’d been born with a deformity — one leg shorter than the other — and because of that she was quite a bit overweight, but it certainly never slowed her down.

I remember she was always busy knitting for us, embroidering and making clothes for weddings and other occasions, cooking and baking, and icing cakes.

I called Granddad Doogie, because I couldn’t get my mouth around ‘Granddad’ when I was very small. He was a dear little man, and an absolute gentleman; everyone says he was the sweetest man. He was a leatherworker, making bags and belts and things for a Christchurch company called Rex Leather Craft.

As I’ve said, I think both grandparents knew there was something different about me when I was just a little child. This thing, this ‘girliness’, was never spoken about, not even in the house, and certainly not in public. They would both protect me; if anyone said anything about the way I acted, or the things I’d do, the way I played, they’d say, ‘Leave him alone, he’s different, he’s alright.’ There are parents even now who struggle with the realisation that their child may be ‘different’ in that way; back in the 1940s, with homosexuality illegal, unspeakable, it must have been a great, great sadness.

In 1948, when I was five, we moved out of my grandparents’ house and into a house that Mum and Dad had built. Leaving Grandma and Doogie’s home was an enormous shock; everything changed, and very much for the worse. I was no longer protected by my grandparents’ love or their moderating power over my father. Whatever happened, if a lightbulb blew, in his eyes it was my fault. I have a crystal clear memory of one Christmas Day at my aunt’s house. We’d had Christmas dinner there, and when we were leaving the old aunties poured the remains of the alcohol the men had been drinking down the sink. I remember them being very religious and perhaps they didn’t want it around. I thought that was quite hilarious and was giggling about it to Mum as we left, and in the street outside Dad hit me in the head, out of the blue, and knocked me clean off the pavement. Just like that. That’s the way it always happened after that, out of the blue and always around the head.

When I was about nine or ten my uncle and aunt were over at ours for supper, and were sitting around the fire after dinner when I crept out of my room to go to the toilet. Dad had been drinking, and when he saw me and said something, I stuck out my tongue at him. He sent me straight through the glass door that night, with one punch. I remember my aunt saying, ‘Oh Alex, pull yourself together!’ He told her: ‘The little bastard deserves it.’

Dad’s disdain for everything ‘arty’ that I did was a regular flashpoint. I used to love to make things, at one stage I had an obsession with making marionette puppets out of paper. Dad would wait until I’d finished and brought them to his chair to show him, then he’d destroy them in front of me, burn them in the open fire, or rip them up.

At intermediate school I won an art award, and Mum and I went up to the school to collect it. We were pretty proud, both of us, but when I got home and showed the prize to Dad, he really lost it. He told me he was going to kill me, had his hands around my throat, and eventually Mum hit him on the head with a coal scuttle to get him off me.

I was thirteen then.

My sister Faye, who was seven years younger than me, never saw even half of it. There was only once, when he was having a go at me, and she giggled, maybe the nervous giggle you make when you’re scared but don’t know how to act. He punched her in the centre of her back and knocked her across the table. I don’t know whether she remembers that or not, but it was the only time I saw him use any violence with her.

He said he couldn’t control me, but in fact he just didn’t want me in the house, and once I was gone, I think it was okay for Mum and Faye.

The last time he hit me I was seventeen. I remember it clearly; by that time I was getting quite clever at getting out of the way when he was winding up for a punch. I would jump clear and say, ‘Have another drink, Alex’ and he’d growl like an animal at me.

But at thirteen I was gone anyway.

Dad had contacted Child Welfare and told them he couldn’t control me. We went to Children’s Court and I was sent to the Christchurch Boys’ Home in Stanmore Road, for a year.

It sounds so grim, for a thirteen-year-old boy to be banished from home like that, but for me it was a relief.

Strange as it sounds, Boys’ Home was a place of refuge.

2BOYS’ HOME

Excerpt from a letter from my mother to me, aged 14

Now Garry boy I am going to ask you a question and I want the full truth from you. Are you still going to make the puppets when you leave the Centre? As you know yourself, you got into a lot of trouble over these and also you know how Dad disliked you doing anything like that. We don’t want you to go back again into trouble we both want you to think seriously about work and going forward getting a good job and settling down like a man when you leave the Centre you want to forget that 12 months and look forward for our sakes as we have both helped you in many ways along the road. Now please Garry give it serious thought. I am looking forward to the day that I get a letter from you saying well Mum, I’ve made my mind up what I’m going to do, but so far you haven’t done that, I suppose it takes time well you must start and think from now just think to yourself, well I’m nearly 17 and its about time I took heed. Well son I think I have lectured you enough now but read that part 2 or 3 times to make sure you see what I mean.

Now I see you wanted more scraps, well Garry I’m being honest with you I’ve burnt every piece I could lay my hands on. I’ve really cleared the lounge room of bits and pieces altogether so there is nothing to send up.

Your loving Mum, Dad & Faye

This letter was never given to me to read — I saw it much later, when my life was handed back to me. It was discussed at a staff meeting, and I do know that my Housemaster, Pat Gooding, thought it would be a terrible thing to give to a teenager with quite enough problems to deal with. Obviously my mother was still trying to keep the peace at home. She had become an accomplished fence-sitter.

Teenage life was difficult for Garry Roberts. Perhaps that’s underselling it a little. It was Hell.

Teachers at Linwood Intermediate, and then later Linwood High, found me strange and unfathomable. I was not without academic ability and my grades were acceptable, but some were concerned about my propensity for drawing fashion and costume sketches in my school books. Others just scoffed.

Beaten with the cane by teachers, bullied by the other boys, I was a total misfit. Even I thought I was weird. It was only after I was taken from school to the Boys’ Home that I realised there were people who could accept my difference and treat me with dignity. This was a real revelation and it took me quite a time to uncurl and lower my defences. I had become introverted, even more shy, and increasingly lived in a dream world where I could enjoy the beauty of colours and the excitement my passion for drawing and design brought me.

Perhaps it was the sheer relief of being away from my father, or that I felt accepted, in a manner of speaking, but Boys’ Home was a watershed experience. It was there at the age of thirteen or fourteen that I first had the revolutionary thought that there was no way was I going to live the rest of my life as a male.

From the start of my time at Stanmore Road I was lucky to find some staff who encouraged my unusual interests. Jim Keane, the House Manager, encouraged me to start making my paper marionette puppets again. The gardener, Mr Graham, helped me make a replica set of the Crown Jewels by cutting a tin can in the shape of the Imperial State Crown. The assistant matron, Miss Read, gave me broken pieces of paste jewellery, and made the waterfall curtain for my puppet theatre. Although it was a welfare environment and not far from home, where everything I did was somehow wrong, it was a haven.

I remember my father finding out about the puppets and coming to Mr Keane in a rage.

‘Garry is not to make those fucking DOLLS!’

Mr Keane was not to be bullied.

‘He’s in my care now, and he’ll do what I let him do.’

Although they were kind to me, my new guardians still clearly thought there was something odd about my behaviour, which is how I ended up in front of Dr Stenhouse.

Every Thursday afternoon, Mr Keane and I would get in the car and drive to the Templeton Centre, a facility known then as the ‘Funny Farm’. Not a very nice term and not at all accurate, as the inmates were mostly children with Down syndrome and other disabilities who’d been put there out of sight by their families. I was taken there every week for afternoon tea (something I used to look forward to hugely, as the food was very good) and to have a chat to the psychiatrist, Dr Stenhouse.

I realised much later that this was Boys’ Home’s way of keeping an eye on me and evaluating my behaviour. I had to write my dreams down for Stenhouse, and in one of our sessions I wrote that I’d dreamt I was walking along the middle of the street and I had long, blonde hair. I’m not sure who I thought I was in the dream, but I looked up at him then and said, ‘When I’m old enough, I’m going to become a woman.’

He didn’t bat an eyelid, that little Scotsman.

‘Would you like another piece of fudge, son?’

Nothing more was made of it, but the conversation was noted in my file.

At around the age of fourteen I went back to school, but eventually found trouble again. The notes from the time (later found by the psychiatrist Dr John Dobson and used to help me change my birth certificate from male to female) talk about ‘truancy and provocative behaviour’. The decision was made to send me to the Levin Boys’ Training Centre, where they sent the boys who had got ‘out of hand’.

My welfare officer, Doug Sellars, was to drive me to Levin. There wasn’t much talk in the car on the way there. Then, out of the silence, he said something unexpected.

‘You’ll be alright, Roberts. They’ll beat it out of you up there. You won’t know what hit you.’

I was fifteen. I didn’t have a clue what ‘it’ was. When we arrived at the centre I was taken to meet a Mr Johnson. I sat in his tiny office looking at my shoes while he tried to talk to me, but all I could think about was the thing Sellars had said in the car, the thing I couldn’t understand.

‘Why don’t you just do it and get it over with?’ I blurted.

‘Do what?’

‘Beat it out of me!’

‘What are you talking about?’

‘Mr Sellars said you’d beat it out of me.’

Johnson looked at me for a long moment, then stood up and left the room. Moments later I could hear him confronting Sellars in the corridor.

‘What have you told this boy?’

‘He’s a wee queer.’ I heard Sellars say.

It was the first time I’d heard that term.

Johnson came back into the office.

‘I’m not going to do that to you, Garry.’

‘But Mr Sellars said you’d beat it out of me and then I’d be alright.’

‘No one’s going to beat you. We don’t do that here.’

He was right — there were no beatings, only insults from the other boys.

‘Sissy boy, sissy boy,’ they’d call me.

Hope can often be found in unexpected places. At the Training Centre I met a group of ladies who gave me, the sissy boy, some hope for the future. Gently and without making a fuss (which would not have been appropriate) they encouraged my hobbies, so violently frowned upon at home, and helped me in little ways to develop them. One of those women was Avis Acres, the artist who wrote the popular Hutu and Kawa series of children’s books in the 1950s. A brilliant artist and a kind and creative person, Avis painted the backdrops for my puppet shows and wrote little scripts for the plays I put on. Sometimes I was allowed to take the shows to Kimberley Farm, an institution much like the one at Templeton. The ‘inmates’ there loved my little performances.

I also had the great good fortune to meet Miss Dorothy Bevan, owner of a florist’s shop and considered the guiding light of floral work in Levin.

I’d been at the Training Centre for nine months when a big farewell concert at the Town Hall was planned for the manager, who was retiring. One of the staff called me in and suggested I be in charge of ‘doing something pretty with the hall’. I had no idea what they meant and said so, but he urged me to ‘just go and put some flowers up’.

So I did. I put together a huge arrangement as a centrepiece, careful to coordinate the flowers and make sure it looked perfect. All the local dignitaries arrived for the concert, Dorothy Bevan among them. She noticed the arrangement, and asked who’d done it.

‘That’ll be Garry.’

‘I’d like to meet him.’

Dorothy took me under her wing, letting me come to her business on a Saturday and work alongside her. One weekend we were working on an arrangement, when out of the blue she announced she’d found me a job at a florist in Wellington. The Training Centre had agreed to release me.

My father hit the roof when he found out. Floristry! It was more than he could bear, but probably better from his perspective than the alternative, which was to have me back at home. Even my mother baulked at the idea, telling me I should think about ‘growing up and becoming a man’.