Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

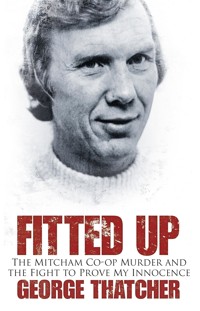

Fitted Up is the remarkable true story of George Thatcher, who spent four weeks in a death cell awaiting the noose for murder following the Mitcham Co-op robbery in 1962. He was later reprieved, but would still serve eighteen years for a crime he did not commit. This is a story of how corrupt policemen 'fitted him up' for the crime; a story of a life of poverty in the 1930s and '40s as a child and young man – a life of petty crime in London's bleak 1950s underworld reminiscent of all those black and white gangster films of the period. Thatcher was a non-violent 'peter' man, a safe-blower. He once blew the safes of three Surrey cinemas in one night. He was a West End 'Jack the Lad', but not a murderer. So when he was sentenced to death following the botched robbery, which he wasn't even a part of, his life was turned upside down. There is a detailed retelling of the farce of a trial. Thatcher's barrister was the renowned Christmas Humphreys, who, during the whole trial, spent barely 15 minutes talking to him. The policeman in charge of the case subsequently committed suicide – could this have been related to any guilt he might have felt over the imprisonment of an innocent man? George was sent to prison for life serving his sentence alongside men such as the Krays, Frankie Fraser and Ronnie Biggs. A riveting tale of poverty, injustice, incompetence, skullduggery, survival and ultimately freedom.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 447

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Foreword by Anthony May

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Afterword by Val Thatcher

Plate Section

Copyright

Foreword by Anthony May

In 1972, the playwright David Halliwell replied to an advert in the back pages of the New Statesman which said: ‘Lifer needs help. PO BOX 142.’ The lifer was a man called George Thatcher who had been convicted of the capital murder of Dennis Hurden during a robbery at the Mitcham Co-op in 1963 and sentenced to death.

He was defended by the eminent lawyer, Christmas Humphreys, who has been credited with introducing Buddhism to the United Kingdom. He had been the senior counsel at the Old Bailey responsible for the successful prosecutions of Ruth Ellis, and Bentley and Craig. The summing up by Mr Justice Roskill lasted six hours and was clearly biased towards the prosecution. The jury was out for just four hours.

After four weeks in the condemned cell, George Thatcher was reprieved, but was to spend the next eighteen years in prison for a crime he did not commit. David, who wrote the 1960’s hit play ‘Little Malcolm and his struggle against the eunochs’ built up a relationship with George, visiting him in prison and encouraging him to write firstly a document telling his side of the story and then two plays. David, myself and the actor Michael Elphick travelled to the Albany prison on the Isle of Wight to see George.

It was a high security jail and after passing through several barred gates we eventually were ushered into a small reception room where George was waiting for us. He seemed in total control as he gestured to the guard to leave us alone. I don’t recall much of the conversation, but I do remember a guard bringing in a landscape painting. ‘The gift for your friends,’ he said to George.

As soon as the Isle of Wight ferry left the shore we went to the very windy upper deck and carefully pulled off the back of the painting and there was George’s first play ‘The Hundred Watt Bulb’ which was put on at the ‘Little Theatre’ in St Martin’s Lane. George wrote another play ‘The Only Way Out’ about his experience in the condemned cell which was put on at the Royal Court. Michael played him in the original production and Brian Croucher, who became a good friend to George, reprised the role in a later production. It received excellent reviews. The Times wrote ‘George Frederick Thatcher has been awarded an Arts council grant of £50 for his play, but what he is likely to receive for it is a spell in the punishment block as his play was sent out of prison without permission.’ George, eventually was given a pass out to see his play performed – but a week after the play finished !

After being interviewed about Michael Elphick for his The History Press biography, I decided to reread the document written by George about his case and his plight. Unfortunately, it had become damaged after forty years in a weather-beaten loft, but with the help of the actors Stephen Greif and Brian Croucher, I tracked George down to a small village in western Ireland where by an amazing coincidence he was living, with his wife Val, next door to some old friends of mine, Neil Johnston and Mark Long. We managed to get hold of, not only the original story, but an autobiography of George’s life which you are now about to read. It is a riveting tale of poverty, injustice, incompetence, skullduggery, survival and ultimately freedom.

Stephen Greif and I have spent many hours going through the Metropolitan Police files and the trial transcript at the National Archives and we are both convinced that George did not shoot and kill Dennis Hurden, the Co-op worker who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. The only evidence against George was police verbal evidence, which was clearly fabricated, and the dubious statements of Phillip Kelly, who on the last day of the trial and just after the Judge had put on the black cap, stood up and said ‘I shot Dennis Hurden.’

To be sentenced to death and then imprisoned for eighteen years for a crime one didn’t commit is the ultimate nightmare and hopefully in the near future he will be exonerated.

My thanks to Val Thatcher, for all her help; David Halliwell; Mark Beynon of The History Press; and above all to George for allowing his story to be told.

1

I was born on 27 August 1929, in a small country town called Farnham in the county of Surrey in southern England. A year behind my brother, Bill, and four years ahead of my sister, Mary (though I know not where they were born, as my parents tended to be a migrant family, who moved house every few years). My mother’s maiden name was Lillian Kitchen. She was a warm and simple country girl to whom life wasn’t over-generous. She had two brothers and a sister named Maud. Their father was a farm labourer who lived in an isolated country cottage on the outskirts of a village called Beckham, one mile from the town of Marlow in Buckinghamshire on the banks of the River Thames.

My mum’s brothers emigrated in their teens, just after the First World War. One went to America to work on the railways in New York, and was last heard of living in Brooklyn, many years ago. The other brother went to Australia as a deckhand on a steam ship and was never heard of again. So there may be lots of distant cousins around the world that we know nothing of.

I am a believer that family are first in all things. That the first rule of life is survival and people born and raised in poverty do not owe allegiance to any establishment.

My mother’s sister, Maud, married a local lad and lived in Beckham all her life. She ran the post office and sweet shop from the tiny front room of her cottage. They had one daughter who also married a local lad, who ran the village pub many years ago.

My father was a fine-looking man, who was born and grew up in Marlow. He had two brothers, George and Bill. All three went into the forces at the beginning of the First World War. My dad, Charley, went into the army with George, who was killed in France in 1917.

Bill joined the Royal Navy and served twenty-two years before losing an arm to gangrene and being pensioned out. He never married, and lived the remainder of this life in Marlow, never worked, spending most of his time in the local pubs, maintaining that beer was the substance your body needed for a good life. He was a happy, kind man who always had love and time for me, often telling me tales of the sea which I’m sure were mostly fantasies he would invent to entertain me. When I was about ten, he would come to the house at five in the morning and take me into the fields to find and collect wild mushrooms, which he sold or cooked for breakfast, before Bill and I went off to school. At one time I had no shoes and wore girls’ slippers and felt so ashamed; we were always very poor.

After the war, my father soldiered in India for eleven years, before returning to Marlow and marrying my mother. Not a good match. He was proud of having been a military man, always acting like a soldier, stiff and upright. I don’t remember him ever being cruel or unkind to Bill or I, though we saw little of him. He was either working at various seasonal jobs on the land or for the council, or in the various pubs in the town. He would try to teach us discipline and loyalty – keep your mouth shut and never tell tales or snitch on anyone – to be strong to survive in an underprivileged world that offered no charity of love for the meek, where those who had, had no time for those who hadn’t, and it’s only the strong who survive.

The first recollection I have, as a very young child was taking a neighbour’s little girl into the middle of the ripening cornfields at the bottom of the small crescent of council houses where we lived, to play doctors and nurses – naughty maybe, but at four it was to play, curious and totally innocent. When my mother found us, she put me to bed for the rest of the day. Later, in the winter I would walk across those frost-covered fields, on my way to junior school, crying with the cold and the chilblains on my toes and the lobes of my ears.

Those early years I could have been an only child, as I have no recollection or images of my brother, Bill, as a playmate or companion – though we shared the same bed and I wore the old clothes he grew out of. We were dirt poor, and I remember my mother telling me how she would take the pram and walk us the long miles to the closing market on a Saturday afternoon, in Aldershot town, when the produce would be sold off very cheaply – she would have 1s 6d to do the week’s shopping to feed three kids, and she would tell how she would take me into the fields to pick the potatoes in harvest time.

We lived in a little village called Ash, before moving into Station Road on the southern edge of Marlow. It was then 1937, and Bill and I attended the local church school where the pupils were graded at twin desks, according to their abilities. Bill and I sat together at the bottom of the class. Our teacher had a gold pocket watch which he kept in a velvet pouch in his waistcoat pocket, regularly taking it out for polishing.

We soon moved from Station Road to a smaller, cheaper semi-detached cottage near the town centre where the loo was 100 yards away at the end of a narrow lane. Next door to us lived the Prices, a family of seven – three young boys with two older sisters – all sharing the same bed in a house no bigger than a matchbox. We were separated by a thin lath and plaster wall that had a hole in the corner which we spoke through. Dickie, their eldest lad, was Bill’s age and they soon became bosom pals and spent most of their time together, occasionally letting me tag along when they went off into the woods or fishing and swimming in the river.

I was a dyslexic, quiet child who spent lots of time exploring the fields with a small mongrel dog that a little girl had given me. My parents were constantly arguing, and I would leave the house to climb over the wall at the end of the lane into the playing fields of the nearby grammar school to get away from it, feeling outcast and alone. One day, my mother took Mary and left, leaving Bill and I with our dad, to run wild in the back streets, into the night to steal the lights from the bikes parked outside the picture house to play ‘Dickie, show your light’ in the unlit alleys around the town.

I was taken into care when I was eight, and put with foster parents some miles away where I stayed till the outbreak of war. My father re-entered the army and my mother and Mary returned, taking me back home. We only saw my father after that when he got his bit of leave.

With the war came rationing, both food and clothes, and we cooked what we had on an old stove in the corner of the room with dead wood we collected from where we could find it.

Before my dad re-joined the army he had worked on an estate as a game-keeper, where the manor house was surrounded by a forest of dying trees that I would often explore or play in. It was a few miles down the road from our home. Once, my father was back with the forces and we needed fuel for the fire as it was winter time and the house was bitterly cold, so I borrowed a builder’s cart and went looking. I collected a pile of dead wood by the entrance to the estate, where my dad once worked, ready to freight away. The lord of the manor appeared and told me to leave it and to get off his land. I headed for home and watched him disappear, then went back and loaded the barrow. My young sister was at home crying with the cold and, to me, stealing firewood was not a big deal. Halfway home, a copper came along on his bike to arrest me and I got convicted for stealing. I was thirteen, and got my first conviction and enrolment on the official ‘s**t list’, which would grow in the years to come.

Mary, as I remember, was around without being obvious, and spent her time with my mother. Boys and girls were not encouraged to be equal in those days – boys went to boys’ schools, girls went to girls’, girls played with girls, boys played with boys – not just sexually and physically different, encouraged to be humanly different and think differently about relationships and behaviour towards each other. Girls were domestic and boys paid the rent. We knew we had a sister and that was about it.

Before school in the mornings, I got a paper round for 2s a week at a shop across the street. At the same time, an afternoon job and after school, running errands and putting up the shutters at a jeweller’s shop. The jeweller would give me money to pay for the postage for his out-going mail and I would pocket the change – till one day he asked me for it, and gave me the sack.

At 5 p.m. on a Wednesday afternoon, I went to the manor house in the centre of town to polish the family silver for sixpence, and I joined the choir at the local church as a choir boy to get twopence for attending practice, and I joined the Protestant Chapel and the Salvation Army when their annual summer outing was due, and I dug a lady’s garden for the cash to buy my first pair of long trousers.

I was growing into a big strong lad and was never bullied, while Bill often had fights at the back of the school yard, but I only remember one that he lost. Then one day the German bombers came to raid the town and missed completely, leaving massive craters in the fields by the river and when they filled with water, I would swim in them. I stole apples from the orchards, strawberries from the fields and pears from the cricket club.

A paedophile worked in the tailor’s shop at the top of the high street, who to me was just a queer guy. I had nothing to tell them, and wouldn’t have done, anyway. Most kids who lack attention are easy prey for paedophiles as they offer kids affection – a reality.

Shortly after this, I had my tonsils out with several other kids. We were bussed to a town 5 miles away to sit in a bare room to wait our turn. We were all terrified. A mask was put over our noses and ether dripped onto it. The smell of it was diabolical. Late in the afternoon, they bussed us home in various states of shock. A few weeks later, I developed a mastoid and was shipped to London for several operations.

When the saturation bombing of London they called ‘the blitz’ was over, life was reasonably normal and we moved to rooms on the top floor of a Victorian terrace in Tulse Hill, south London.

Then came the doodle bugs – the V2 flying bomb, one of the first generation of rockets, designed more as a terror weapon than anything else. These things made a loud popping noise as they flew low overhead and could be heard miles away. They were totally indiscriminate, launched from sites in France to destroy London, and kill and demoralise.

I left school at fourteen – academically a non-starter. I got a job in a local pet shop, delivering pet food in the area on a bicycle, six days a week for £1. Bill worked next door as the storeman for a local grocer. In those days, the shops shut for lunch – 1 p.m. to 2 p.m. – and we would ride our bikes home, a mile away. Some days, Bill would shut the warehouse and have lunch on the sacks of grain in the back with the ginger-headed counter girl from the grocer’s shop, and tell mum he had to work over. He was more mature than me in many ways.

One Tuesday, as I remember it, we were at home having lunch – a lump of bread and a piece of cheese – and we heard the sound of the doodle bug coming over, and we all sat silently, holding our breath. When the engine stopped, the bomb came down – and it stopped right above us and cracked down in the street below. We were up and out in seconds, helping to find and rescue people from the debris of the house, and I lifted a three-year-old child with no face left, from beneath the rubble – that seems like only yesterday – and I never took the bike back to the pet shop or worked there again. Shortly after this we were bombed out ourselves and moved to Kennington Oval, further into central London.

Bill and I were growing fast – over 6ft and filling out. Both a little on the wild side – never staying in one job for long, and no concentrated interest in anything. Bill seemed to work more regularly than me and often worked as a prop-maker and stagehand in West End theatres, while I did more bumming around, as London became more vibrant with the fever of war and a brooding atmosphere of expectation for a Normandy invasion.

There were foreign soldiers everywhere and most of them were GIs, and many of them were living on nervous energy as they lived from day to day, waiting to invade Europe and die a hero’s death – to leave their mothers in tears. They all seemed like glamorous guys in smart uniforms with pockets full of money, full of bravado and uncertainty and wanting a good time. They all seemed so wealthy and so eager to treat. We thought they were all millionaires who wanted to give it away. We were all too young to know that they didn’t all come from Hollywood, and that half of them wouldn’t live to see another Christmas.

All the young girls had a field day as they ‘did their bit’ for the morale of the troops. This was now 1943 and I was still fourteen, learning to live by the day, and the western world was rapidly revamping its Victorian attitudes. Sex before marriage was popping up everywhere. Divorce was only for the film stars, although being a virgin on the right way was a desirable achievement. The GIs opened many doors to new ways and everybody loved them, though some, of course, were straight out of the hills and as naive and ‘the good life’ as the rest of us. They opened the Rainbow Corner in Piccadilly – a massive PX store and leisure centre in the heart of London, like a honey pot in a land of flies. It became the place where things were happening.

Bill and I were working at a fruit and vegetable warehouse in Covent Garden – me as a porter, Bill as a delivery driver, taking fresh fruit and vegetables to the Ministry of Defence and various hotels in central London, on a horse and cart. Bill was sixteen. He would get up at 6 a.m. and take the underground train from the Oval to Leicester Square to clean and feed his horse at a stable in Soho – that poor old horse never saw a stream or walked a field, and Bill drove the cart round the streets as if it was a chariot. Then one day he had a row with the firm’s salesman, who he punched on the chin and laid out in the gutter, and got the sack.

I stayed on a couple of weeks till I got the sack myself. I had been sent out with a young delivery driver who nicked a 28lb block of butter from the kitchen of a hotel we delivered to. He dropped the butter into an empty fruit box in the back of the van and took it to a friend’s. He saved the fruit box in the back of the van with a lump of butter stuck on the side. We were nicked when we returned to the warehouse – me as an accomplice – and in the magistrates’ court the next day I was fined two quid and got the sack. I was just fifteen.

We often nicked things to finance our lives. We all got into minor bits of trouble, though nothing of much account in those early days. There was so much temptation in a world of uncertainty that nobody really cared. There was challenge in the atmosphere, and a black market everywhere, and in the unconsciousness of the times, many things we got up to on a regular basis were a feature of the times and seem now much more bizarre than they really were.

The West End was then becoming the centre of the universe for the street kids I was growing up with. I was making new friends all the time, and doing all sorts of things, and gradually growing into the subculture in a quite natural way. We had no peer groups to imitate so we did whatever we wanted to do – and we were always looking for opportunities. We became known and identified as ‘spivs’ – guys who lived on their wits – sharp dressers, in suits we called ‘drapes’ with padded shoulders and long lapels, cut away just below the bum. They had to be tailor-made and very expensive, and it would take weeks to hoard enough money to pay for them. Our shoes we called ‘creepers’ – soft, silent soles to creep around on – moving around without making a sound, living one day at a time. Interested only in the moment – or what was on at the cinema – and more energy than you know what to do with. I worked when things got desperate, and gave my mother some money each week. Otherwise, it was anything goes.

I guess there were people around who considered our behaviour antisocial at times, but what can anyone expect from that sort of environment? We lived life to the full with what we had, and being young and without control, we took nothing seriously and most things for granted.

In those early war years, the London Opera House in Covent Garden was used as a dance hall, but by the time the Yanks came in ’44, the dance had moved to the Lyceum just down the road at the corner of the Strand, and that soon became a rendezvous for the budding youth from in and around the Elephant and Castle, the Lambeth Walk, and the Old Kent Road. Bill and I soon found our own way in, which wasn’t through the front door. We discovered we could open the rear exit doors from the outside with a thin iron rod with a hook on the end. We kept this rod on a ledge above the emergency doors of the Lyceum, and used it on all the cinemas and theatres in the West End to see the shows we couldn’t otherwise afford.

Things were so much easier to do and get away with then, as long as you played the game and lived by the rules in your neighbourhood, you were accepted. Nobody seemed to care very much about anything, so long as you didn’t give anyone any trouble – role models, for what they were, were Sinatra, Humphrey Bogart, Edward G., James Cagney, Robert Mitchum, Burt Lancaster and any other macho, smart, tough guys. It was more important to be smart than tough – and clever, rather than thick. None of my friends seemed to care about drugs or booze, although both were available even then. Cannabis and cocaine were in the jazz clubs and seemed to be restricted mainly to the music world.

My best friend at the time was a couple of months older than me. His name was Chick Jacobs, he lived by the underground station at Kennington Oval, just around the corner from the Oval cricket ground. His dad was a pickpocket who worked with a bunch of other ‘dips’ and was often away for weeks. He was also on the run from the army so didn’t feel safe at home. We lived behind Kennington Park, and I would wander over to Chick’s about 10 a.m. and chat with his mum and aunty Flo, who was living with them (her husband was away in the forces and she was in her early twenties). I can’t remember the exact details, but I do remember her and me standing in a doorway opposite Chick’s house, watching out for the military police because Chick’s dad was at home. We acted like lovers, and she tried to seduce me but I didn’t know what to do, and I was tall and she was short – and it was all very awkward – we didn’t get beyond some heavy petting and she got really p****d off with me.

It was about this time that my father died, after being wounded in France. I remember my mother having to go to Manchester where he was in hospital, and I had to collect my sister, who was ten years old and staying with an aunt, and take her on the train to visit him. He had a head wound and didn’t live very long. We hadn’t been much of a family really – nevertheless, I felt the loss and remember it vividly, although I cannot remember how supportive I was to my mother at that time, or how it was for her.

Our home in Kennington was very basic – camp beds in otherwise bare rooms. We didn’t have much going for us, but neither did the rest of the neighbourhood – which consisted mainly of bombed and derelict houses – no wonder I was a bit wild and insensitive in many ways. I look back on that period with both wonder and regret. That was my world – lacking understanding and short of wisdom, with loyalty only to my friends – never giving a second thought – thought was somewhere in the back streets, hidden in the debris. My mother applied for a war widow’s pension and discovered that she wasn’t entitled – as my dad already had a wife in India with two children!

Chick and I met up in the mornings to plan our days to suit our moods. Sometimes we would wander off to meet friends outside Jane’s Café in the Lambeth Walk, play dice with them on the pavement and get the local gossip, then maybe spend the rest of the day mooching around the West End to see what was going on – or look for earners and fool around. One day, Bill was with us and we picked up a wad of yesterday’s unsold newspapers from the doorway of the Turkish baths at Charing Cross, then sold them in the rush hour outside the underground stations, when people were too busy to notice what they were getting – stupid stuff like that.

I was still only fifteen, and already 6ft when the war in Europe ended, and when it did, everything went wild for a few days – singing and dancing in the streets of central London, like nothing before. People came from everywhere, by the millions it seemed, and it was often impossible to move around. This was the war in Europe, the one in the east with the Japanese was on its way to ending a few months later.

Both Chick and I began bumming around, getting bolder and a little more reckless. We often started the day by waiting at the traffic lights on the corner where we lived. Waiting for lorries going in the direction of the City or the West End. Lorries in those days were mostly flat-backs with canvas canopies. When one we fancied stopped for the traffic lights, we’d wait for the lights to change and as the lorry moved off we would jump on the back and go wherever it was going, then jump off when we wanted to. If there was anything sellable on the back, we’d lift it. We always got on or off these lorries when they were moving so the driver wouldn’t notice any unusual movement.

It was on one of these excursions, a couple of months after the end of the war, that we landed up on Leadenhall Street in the City. The City of London is the business centre, and Leadenhall Street is where all the major shipping companies have their headquarters. I had romantic ideas of sailing the seven seas and going to exotic places. In one of those shipping offices I was given an application form to fill in so I could join the merchant navy. They had to be signed by my mother as I was just sixteen. A few weeks later, a letter arrived from the Seaman’s Federation for me to report to a training ship on the Bristol Channel in January 1946. It was now October 1945.

Walking home late one night, Bill, Chick and I had been wandering around the West End. The buses had stopped as it was past midnight. On the way we decided to break into a large wine warehouse we had to pass. We certainly weren’t thinking of emptying the place, as we had no transport. I don’t know what we were thinking, if anything at all. Bill was pretty good at getting into places – he seemed to have a knack for it – and in no time at all we were inside doing our best to drink the place dry. We came out of there several hours later, hardly sober enough to stand and, within no time, we were nicked for being drunk and disorderly. By the time we had sobered up it had been discovered that the wine place had been raided, and we were nicked for breaking and entering; and I’ve never since acquired a flavour for booze.

We were sent for trial a couple of weeks later and Bill and Chick got thirty days. I would have got the same if I hadn’t been due to leave London to go to sea. Instead I was given two years’ probation, which was considered better than going to jail – though, like most things, it had its shortfalls. By the time Bill and Chick got out of jail I was gone.

I guess this was really the point in time when Bill and I drifted in separate directions and into separate lives, never living together again, though we would see each other when either of us were around. By the time I came back from my first trip away, he had taken up with a girl, got married and moved into his own place with a regular job making stage sets, before he was conscripted into the Royal Navy. So we never seemed to be in the same place at the same time very often. When he came out of the navy he had a four-year-old daughter called Christine, and discovered that his wife had been fooling around – so he quit and landed up in Australia.

I don’t know what happened then, or if they were divorced, only that Bill signed on with the P&O shipping company who were then trucking families to Australia on the £10 emigration scheme. He had a nine month contract and signed off in Sydney, worked a while in the outback with a pal named Jeff; formed and performed in a travelling entertainment group; met and married a lovely Oz girl named Loll, in MacLean, Queensland, and had two kids. They spent fifty years together. Bill was deeply wounded by his life in England, and blanked it out completely when he settled in Oz and would never talk about it.

But before that, after the trial and the probation order, there were a few days before I had to leave and I was bumming around late one night with an older pal in Oxford Street, just around the corner from the PX. He introduced me to a girlfriend standing in the shadows of a doorway. Her name was Doris Peach, and she was every bit a peach. She was a very attractive twenty-five-year-old hooker with a regular pitch. My friend wanted me to get laid before I went away, and Doris liked the idea. She took me home to her flat in Black Lion Yard in the East End. Black Lion Yard was a tiny narrow street of Jewish jewellery shops and she had a flat above one of them.

Doris was my first serious sexual experience, and all that went before was just fooling around. We liked each other, and over the next few years we would occasionally meet up and spend time together. There was never any commitment between us and never anything prearranged. I would call her up and go over, and we would spend a bit of time together; then I’d disappear until the next time. I don’t remember why I stopped calling. I think I’d been away for a while, and we both lost interest. Other things were happening, and now I can’t remember what she looked like, except she had blonde hair and beautiful legs; though I don’t really remember them either, only that they were beautiful and that our relationship was totally undemanding and very laid-back.

2

In January 1946, I joined a training ship in the Bristol Channel on the West Coast. It was an old four rigged German schooner called the Vindicatrix. We slept in hammocks on the crowded lower decks, and washed at six in the morning in cold water on icy upper decks. It was so cold in January that we had to break the icicles from the rigging, and row the life boats across the Severn Estuary in bitter winds. We were there for two months to learn basic seamanship skills like compass reading and sailors’ knots, and pass lifeboat exams, without which you weren’t allowed in the union. Then you got your seaman’s book to record the ships you sailed in.

As soon as the course was finished I signed on at the Seaman’s Pool at London Docks. The Pool was then the job centre for seamen where you would sign a contract to sail on whatever ship you chose to go on. At the Pool they told you what ships were in port, what hands the ship needed and where it was going. I signed onto one of the newer motor vessels that were replacing the coal burners. It was called the Pardo, belonging to the Royal Mail Company and sailing to South America. It was a 5,000 ton cargo ship with a crew of twenty-five.

In those days there were no container ships, and all cargoes were loaded on and off by stevedores which could sometimes take a couple of weeks – which meant two weeks in port and time to see the sights and visit the bars. I can remember that first trip quite well – as we all remember the first time for most things.

All ships’ contracts in those days were for two years, and you could sign off when the two years were up in any Commonwealth country in the world that the ship docked in. (At that time, over a quarter of the world was British Commonwealth.) If, in that period of two years, the ship returned to the original port of contract the whole crew would sign off and then sign a fresh contract if they wanted to. Most seamen are wanderers and all ships are different; so, new ships, new places, new crew, new friends, and new experiences, was the way of life for most seamen, who couldn’t really cope with a 9–5 job. Going to the same place every day, the same routine of having to get up every morning at the same time, catch the same bus, and waste the time travelling to work. It all seemed such a waste to earn money to pay for a ride that was more a burden than a joy. I thought there must be better ways to live than that.

The Pardo was going to be in London Docks for a week, unloading corned beef from Argentina. I signed on as the galley boy, and put on 8lb in the week before sailing for Liverpool. I had never before had access to so much food, or even dreamt that I would peel so many potatoes or wash so many dishes. We were in Liverpool for ten days, taking on cargo for South Africa; including four race horses for Rio in horse boxes on the after deck. The night before we sailed I went to Lime Street, hoping to meet ‘Maggie May’ – the girl that every sailor told stories about, and who had broken a thousand hearts, including Rod Stewart’s. ‘They’ve taken her away,’ they said, so I went to the movies and saw Brief Encounter and thought it was wonderful. In the morning, as the sun rose, we set off for the Canary Islands. For a wage of £2.50 a week we were going to Rio de Janeiro, and I was having a good time except for the endless sacks of potatoes I had to peel by hand. I would sit on a capstan by the ship’s rail with two buckets of water and peel away, watching the sea for dolphins while getting a golden sun tan. We refuelled in the Canary Islands, where small boys actually sold canaries in bamboo cages on the dockside. Then headed south-west for the ten day trip across the South Atlantic to Rio. Watching shoals of flying fish, surrounded by the calm silence of the deep blue sea, and the circling horizon a straight line everywhere. The sun as wide as your open arms, gradually sinking out of sight – then Rio with the early dawn, its sky scrapers rising slowly through the haze like enchanting fingers, larger and larger as they filled the horizon ahead in a mystical, futuristic way, like no other.

There are many things I recall of those days, which mean more to me than they will to anyone else, and as time moved on, in years of solitude these memories lived with me. Sitting on the stern deck late into the evening, listening to old hands spinning yarns of places they had been, sights they had seen, the lovers they had in exotic places. All the stuff that captures the imagination, and leaves you wanting more; enchanting tales to fill your dreams, while sleeping in makeshift hammocks on the open decks, covered in the warm, South Atlantic breeze.

Rio was sunshine and samba, and my pay was gone on the first day. My free time I spent on Copacabana beach, daydreaming and watching the golden legs of the girls going by. Most of that Copacabana skyline was funded by ex-cons from Devil’s Island who had prospected the jungles of Brazil.

From there, we shipped south to Santos, and from Montevideo to Buenos Aires, then back to Rio, to London and one day’s leave for every week away. That gave me three weeks to bum around and catch up with my friends – and occasional nights with Doris, and freebies at the cinemas and dance halls.

Months later, I was working as a steward on the cross-Channel ferry, from Dover to Calais (part of the Golden Arrow link from London to Paris). Tuesday was my free day. The ferry docked in Dover at 5 p.m. on Monday, and I would catch the boat train to London at 6 p.m., and join up with my friends at the Hammersmith Palais at 8 p.m. for the regular Monday spot, where I met my first regular girlfriend.

Her name was Betty Webster, and she wore draped jackets with padded shoulders and wrap-around skirts. She lived in the Old Kent Road with her parents, and younger brother who suffered from smelly feet. Betty was two years older than me and worked as an accountant in the City in the day time, and was part of the regular crowd in the evenings.

The Hammersmith Palais dance hall was the place to be on a Monday night. Ted Heath’s band was the big noise of the time, and his lead singer – Paul Carpenter – crooned like Sinatra. Our crowd were into jiving – which entailed a routine with a regular partner – and after the Palais closed that night, I met Betty. She gave me her office phone number so I could call her the following day, before returning to Dover. So began a regular Monday meeting until I quit the Golden Arrow.

New Year’s Eve that year was on a Monday, and plans were made for partying, but on that morning I was told the company wanted to transfer me to their sister-ship in a place called Folkestone, which meant I would lose my day off and I would miss the New Year activities. So I quit, and that night a crowd of us gate-crashed the Chelsea Arts Ball – the major event of the year, and the first since the end of the war.

A month passed before I joined another ship and sailed for America and, when I returned, the new meeting place was the Friday night dance, in a hall above Burton’s tailor shop in Brixton. The dance was over, and I was going to spend the night with friends in the Walworth Road, so we caught the tramcar on the corner. The tramcars were like you see in San Francisco or Hong Kong – rattly iron boxes that rocked and rolled on narrow lines down the middle of the streets. We had been on the top deck, and were getting off at the next stop, on our feet heading for the stairs, when the tramcar swerved on a sharp bend and I lost my balance and fell between two bench seats. I raised my arm as I fell towards the window and the glass shattered, cutting through the ligaments of my left hand, putting me out of action for several weeks. It was almost a year before I could use my hand normally and I never went to sea again.

Out of money and out of luck. The union gave me two quid a week, not enough for an extravagant lifestyle or to put enough food into a hungry face. So, I looked for other ways, and I soon teamed up with some other guys who were in the salvage business. The oldest one was about twenty-seven, quite old by our standards. He had TB and so was physically unfit for the armed services. He also had a truck, and we would meet up in the morning at a local café in the Lambeth Walk for a breakfast of beans on toast, then cruise out to areas, still sparsely populated, where there were streets of large empty houses waiting to be renovated from the war damage.

You didn’t have to break into these places, because most of them had no doors or any windows and we would work away like any normal working crew and remove the lead, which we took to various scrap merchants. Scrap lead fetched a high price, and in one day each of us would earn what most workers earned in a month. It was, of course, a short-lived opportunity. Despite the ravages of war, people were returning to London, and you couldn’t go to the same street too often without being noticed. The scrap merchants never asked questions and were as keen to do a trade as we were, and there were quite a few of them about. Some even ordered items like sinks from us. They all seemed to have larceny in their hearts, like everyone else I knew. When the salvage business began to dry up as the empty streets began to fill, we would nick the lead from one merchant and sell it to another, and life would go on.

Betty and I were going steady, spending more evenings together, and late nights on the sofa when her parents had gone to bed. Nevertheless the rules were rigid. I would walk the 3 miles home in the small hours, as regular as clockwork, with a pain in the groin and ‘no satisfaction’, as the Rolling Stones would say. That’s the way it was. While I became reluctant to sign on the Pool for another ship, and kept putting it off – I was doing all right so why bother.

Then Chick and I arranged to meet one evening to pick up a load of lead from a site near Buckingham Palace. It was, in effect, once too often and we were nicked. In court the next morning we were found guilty by the magistrate, and each given three months and then the realisation came with a jolt how suddenly and quickly life can turn around. One day you’re a free bird, doing your own thing and the next you’re in chains. I was nearly eighteen, and found it extremely difficult to cope with being caged. I hated every moment and I wanted out and back to sea. Of the three months I would serve two, and that seemed just about forever, an eternity, a space of time that would never end.

In retrospect, this was the start of my adult education, although I couldn’t see it then. At that age and period I was growing, and not reflecting. I lacked the foresight to see where I was heading, and within me there was a stubbornness which caused me to resist the things I could not respect. So, in many ways I became, from then on, a product of the system. A system that is self-propelling and in the broad sense serves only its own interests.

One week into the second month and the clockwork frequency of the routine was beginning to wear me down, and the mindless brutality of a system going nowhere was starting to engulf me. I was no longer an individual, only a number in a chain of numbers that made up yet another chain of numbers, and there were so many numbers that when you got towards the top, the numbers changed. That’s jumping ahead a bit, and I hope that my reference to numbers becomes clearer later.

We were only allowed two letters a month, and received the same number in reply – two small pages. If other letters came we were told that they would be thrown into the waste bin. A visit for twenty minutes, behind glass, after one month served. No newspapers, no radio, no contact with the outside world, locked alone in a tiny concrete cell in silence for twenty-three hours a day and the outside world, what we call the real world, became unreal, and all life out there became a fantasy.

We walked around a barren yard for one hour each day in circles, paired off with another young convict whose crime, in all probability was of no consequence and no threat to humanity. We were only allowed to talk on the exercise yard, then only to the person we were directed to walk with, not to the couple behind us or to the couple in front, and the pace we walked was controlled by one of the Home Office thugs standing around the circle. Those outstretched arms going up and down like a railway signal, spacing us out, equal distance apart. I hated every moment, and felt completely trapped. I made no friends on that exercise yard, at least none that I can remember, though some faces I would recognise in other prison yards in future years.

And there began for me the reality of what prison was all about, and it wasn’t about compensating society as a whole for my sins, although that was the crap the law enforcers would have us believe. This style of internment was not about morality, as there wasn’t any morality in sight. It was about control, the pecking order, with lots of revenge and plenty of stupidity.

I had completed three weeks of the eight that I was to serve on that three month sentence, when I was issued with a production warrant to appear back in court, for violation of the previous probation order that I had been given twenty-three months earlier. I hadn’t seen much of the probation officer. I didn’t inform him when I was home, as I saw it as aggro, so we didn’t have anything going for us in terms of a relationship.

When I appeared in court a week later, I wasn’t represented and, as far as I can remember, I didn’t have a lot to say. I probably said I was sorry and I won’t do it again, and of course I was sorry. I was sorry to be there as I knew I was going to get hurt. The vast majority of people live on double standards, and the politicians and law enforcement on treble, and we are only ever sorry for being caught. Everyone is sorry for the transgression when their luck runs out and the law lays its hand on your shoulder.

The court, in its wisdom, sent me to a borstal institution for three years. Borstal was a so-called correction system for young offenders aged between sixteen and twenty-one, and like other punitive ideas before and since was a complete failure and was subsequently abandoned. There were several of these institutions around the country. Some were open, some were closed. The open ones were ex-army camps or military hospitals, redundant after the war and now taken over by the prison service to house young people for a course of training.

After the sentence there was a three week assessment period in the borstal wing at Wormwood Scrubs, which was one of the major London prisons for men. A chief officer ran the wing. He was shortish, very thin, had a very loud sergeant major voice, wore a peaked uniform cap that looked too big for his head, and spent most of his time shouting at boys to get their hair cut.

Chick was let out on my eighteenth birthday, the same day I got off the bus with a bunch of other unfortunates to begin this course of training. The place was called Northsea Camp and that is what it was, a group of army sheds turned into dormitories, each shed given a name and called a ‘house’. Within the hour we were fed, located to a house, dressed in prison shorts and in the gym working out under the instruction of a gym master. We were informed that the object of the exercise was discipline and fitness. Purity of the body leads to purity of the mind, or so they say, but, after two months in Wormwood Scrubs with one hour a day shuffling around a yard, just thirty minutes in the gym and you’re ready to drop dead. The emphasis was on fitness and hard work. Up and out in the mornings at 6 a.m. for twenty minutes of physical jerks, breakfast of porridge and beans, then out to the mud flats beside the camp to reclaim land from the sea.

The camp was located in that part of the Norfolk Broads known as ‘The Wash’. Miles of mud flats which needed protecting from the incoming tides that swept in from the North Sea and flooded the land. We had to create barriers on the shore line when the tide was low – built from the mud, shovelled into open containers on narrow tracks, then pushed up the ramps to empty on the top. Soulless, destructive labour, advocated by those who wanted to teach their wayward youth a lesson, and the harshness of the task compounded by the high tide of the cruel sea, washing the mud back from where it came. And those cold winter days, some shrouded in a hazy kind of mist that closed the world. Bone-chilling, icy east winds that swept across the mud flats, piercing to the core, blistering your hands and making your balls look and feel like walnuts. So physically demanding that it compounded a hatred for everyone and everything associated with it.

Mindless. That kind of hatred is not a good emotion. Fitness and intensive hard labour won’t control the mind either. Of course, disregard sex, desire, hunger, humour and daydreams, it may raise the spirit to something noble. Who knows?