23,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Merlin Unwin Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

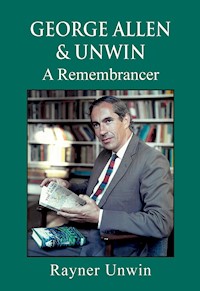

George Allen & Unwin as a publishing imprint reflected a cross-section of the intellectual achievement of the Twentieth Century. In his Remembrancer, former Chairman Rayner Unwin traces the vicissitudes of his own time with the Company. It is a digressive and personal history, with reflections on the delights as well as the dangers of a style of publishing that is now fast vanishing. He particularly focusses on his memories of publishing famous authors including: • JRR Tolkien • Thor Heyerdahl • Bertrand Russell • Roald Dahl This frank and elegant publishing memoir covers the eventual take-over of the Company. A Remembrancer brings to life this sequence of events which led to the winding up of a distinguished firm.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

i

GEORGE ALLEN& UNWIN

A Remembrancer

Rayner Unwin

1925–2000

Contents

iv

‘You may well ask why I write. And yet my reasons are quite many. For it is not unusual in human beings who have witnessed the sack of a city or the falling to pieces of a people to desire to set down what they have witnessed for the benefit of unknown heirs or of generations infinitely remote; or, if you please, just to get the sight out of their heads.’

The Good Soldier Ford Madox Ford

PREFACE

Some Reasons for Writing

You too may well ask why I write. My father, Sir Stanley Unwin, my cousin Philip Unwin, and on a more domestic level, my brother David Unwin, have all traced the history of George Allen & Unwin and its founder from their own viewpoints. What need is there for another account? Especially, I must admit, a disjointed account that qualifies neither as a straightforward autobiography nor as a consecutive company history. While I was still involved with the firm - a period of nearly forty years - I did not consider that any more needed to be said. Now, having contributed both to its enhancement and its decline, I am not so sure. Father always sounded so confident in his book The Truth about a Publisher. Even the echo in its title of his unchallenged text-book on the profession that he had mastered and led throughout the middle decades of the century is an indication that his account does not brook contradiction. Indeed, there is nothing factual to question. It is by the interpretation of character and events that Philip in The Publishing Unwins and David in Fifty Years with Father have given a fresh and human dimension to the image of infallibility that father created.

Besides, there is an end to the story of the publishing company that none of the previous books have touched upon. This is an area about which I want to leave a record in order to complete the history of George Allen & Unwin. It is not an autobiography, but inevitably it is a personally-slanted story, concentrating on the years between 1951, when I joined the company, and 1990, when I sadly witnessed its demise. I have not written a continuous narrative, but instead taken distinct aspects of my publishing experience that I intend should give via digressive, anecdotal and I hope atmospheric account of a style of book publishing that has now, regrettably, almost totally vanished.

The firm I entered was editorially-led, medium-sized, and self-financing. It published according to merit rather than market, and maintained trust with its authors and with its bookselling customers. These were the values that my father held to be self-evident, and he died in the confidence that they would continue indefinitely. Unhappily they have not, and I doubt if he would appreciate the changes that have occurred within the industry in the last twenty years. These changes, insofar as we experienced their effects and were eventually overwhelmed by them, I have also tried to record.

By way of prelude to my account of the later years of George Allen & Unwin I have included some reflections on the firm that preceded it. Because it formed no part of his own life-story, George Allen does not feature in my father’s book; but in the 1930s he commissioned the book-trade historian, F.A. Mumby, to undertake this task. Mumby’s premature death and the onset of war delayed its publication, but a small book, From Swan Sonnenschein to George Allen & Unwin Ltd, did eventually appear containing Mumby’s essay on the strange publishing relationship between George Allen and John Ruskin. I do not pretend to have added much to Mumby’s research and to a subsequent thesis by B.E. Maidment except at a personal level. The firm I joined half a century after Ruskin’s death still had a faint aura of his influence. Although father was neither a sentimentalist nor an historian I have always been curious to look back at our roots. I felt that the retention of George Allen’s name meant more than (as father put it) keeping our firm at the top of alphabetical lists. Ruskin too had links to my imagination, through Arthur and Joan Severn, my maternal ancestors, and because of the chance that had brought Kathleen Prynne and The Gulf of Years my way. I have also found it possible to detect at a distance in time some strange parallels between the small beginnings and complicated endings of our successive companies.

To the history of the early years of George Allen & Unwin I can contribute nothing. Father’s own account needs no embellishment, though Philip and David give invaluable character-portraits of the force behind what was essentially a one-man firm. During these years I was born, went to school, joined the Navy then, after demobilisation, viito University, and eventually, in my late twenties, became available to be hastily trained and installed in Museum Street as an apprentice publisher. Only at this stage can I start my narrative. My first chapter attempts to record the almost forgotten, incredible world of a reasonably-typical, medium-sized book-publishing firm into which I was introduced in 1951. It was not so small an organisation, nor run by such distinguished eccentrics, as The Hogarth Press about which Richard Kennedy has written so vividly, but I can recognise many of the quirks that he experienced twenty-three years earlier from my first years at Allen & Unwin. The events of the immediate post-war period have already been recorded by Philip from an editorial point of view as well as by the Governing Director himself: my contribution is only the observation of a fresh pair of young eyes.

Father’s autobiography took the story to 1960, and Philip’s book covered scarcely ten years more. My apprenticeship did not last many years, and soon I became increasingly involved in many aspects of the company’s decision-making - its structure, its books and its sales. I have made a rough division in what I have written between our editorial achievements and managerial matters, though my digressiveness has involved overlaps. In general, however, I have devoted a chapter to each of these aspects up to the period soon after father’s death when I had become Chairman; and a further chapter on each aspect from that point until the 1986 merger, leading before long to the take-over by HarperCollins.

Like my father before me I spent a lot of time selling books and visiting customers and agents abroad. I also followed his example in working for the Publishers Association. Both these aspects of my time outside the office I have written about separately. I have also written two chapters at disproportionate length about my long friendship with Tolkien. It was of all our relationships with authors the closest, the most complex and, ultimately, the most profitable; and as it was from the very beginning a highly personal association I wanted to record it in commensurate detail.

The sources I have used for writing on these various topics have included, in addition to the books already mentioned and my personal recollections, the company’s minute books, the council minutes of the Publishers Association, a compete set of George Allen & Unwin’s catalogues and lists, and the correspondence files relating to Tolkien viiithat are now held by HarperCollins. In addition there have been a few relevant documents that John Taylor or I still chance to hold. I have not consulted the most daunting mine of information of all, the Allen & Unwin correspondence archive from the time of the firm’s foundation until 1968, which is held at Reading University and is currently being catalogued on a data-base with help from my father’s Charitable Trust. Before it was moved from the basement of Museum Street it occupied over a hundred tightly-packed, four-drawer filing cabinets. Now, although it is gradually becoming more accessible, its detail is still overwhelming: it contains, for example, 20,000 Reader’s Reports alone.

There are two principal reasons why I have not even attempted to surf this archive. In the first place it stops abruptly at the year of father’s death which, coincidentally, was also the year when we abandoned central filing. Subsequent files were, regrettably, thrown out, partly after the move from Hemel Hempstead, and finally after the take-over by HarperCollins. It would have unbalanced what I have attempted to do, to have a mass of detail relating to the early, reasonably well recorded, period of my time at Allen & Unwin and nothing comparable about the final years. My second reason for not cherry-picking the files at Reading is my hope that, one of these days, their presence might encourage a truly-detached scholar to write a history of the firm. Those of us who have written so far have put down personal markers, but have been too closely involved to have attempted such a task dispassionately. Yet it deserves to be done.

It seems inevitable that once a publisher retires he picks up the pen himself. This was certainly the case with my three editorial colleagues who left us during the seventies, and I seem to have fallen into the same trap myself. The firm and (as I hope will be apparent in the chapters that follow) I myself owe so much to them that it seems appropriate to salute the labours of their retirement in that of my own. My father, who never dreamt of retiring, speaks for himself; but I should add a special word of gratitude to Charles Knight, who did not leave his mark in writing, but whose influence on me and on the Company I hope this book will make plain.

Philip was the most active writer in retirement. One of the first tasks he undertook was an eighth edition of father’s The Truth about Publishing. It proved a difficult and not entirely satisfactory job. ixPublishing had changed so radically even since the last edition that it needed more than minor adjustments to make it relevant. Father’s broad philosophy was still valid, but as a practical text-book it really needed to be completely rewritten. Philip revised it as best he could, but he admitted that it would be for the last time. He also undertook two histories of our family; one, which I have already mentioned, dealing with The Publishing Unwins - principally T. Fisher Unwin and my father, with both of whom Philip had worked - and the other with The Printing Unwins - the five generations, starting with Jacob Unwin the pioneering ‘steam printer’, and descending through Philip’s branch of the family who successively worked in Unwin Brothers. Lastly Philip made his own contributions to the list he had been so instrumental in establishing, and wrote two books about Travelling by Train.

Charles Furth who had, long before, written two, often reprinted, school books You and the State and Life since 1900, had during his last years with the firm left London and lived in East Anglia, within occasional reach of Hemel Hempstead. It was probably as a reflection of this move that he wrote his last book on Old Farms and New Farming, which he subtitled ‘A Layman’s view of the Land’.

Malcolm Barnes had written more than any of us, but seldom under his own name. His abridgements of Augustus Hare’s autobiography and innumerable translations, mostly from the French, gave him a second place on many title pages; but even a book that he created after he had retired, based on interviews and tape recordings given to him by Tensing Norgay, and which we published under the title After Everest, played down Malcolm’s virtual authorship. But that was Malcolm’s style: coming from a good Quaker background he never sought public notice. It was through Malcolm’s mountaineering contacts, notably the Swiss Foundation for Alpine Research, that the opportunity of writing Tensing’s book had come his way, and I treasure having met him once at Malcolm’s house while the work was in progress. Only at the very last, in 1984, did Malcolm stand as an author in his own right with his biography of Augustus Hare: Victorian Gentleman.

For my part I had during father’s lifetime been sufficiently sheltered to write and have published a couple of books and researched a third. But for more than twenty years I had put any further writing aside. After the sale of Unwin Hyman in 1990 I returned xto my unfinished book on William Barents and soon completed it. It was not so easy, however, to find a publisher. My style and choice of subject typified the ‘middle ground’ in which I had written and been published earlier in my career. But now things were different. The library market had shrunk, the number of titles published in this country alone exceeded 100,000 each year, and successful publishing all too often meant strident marketing. I did eventually find a small publisher who was prepared to take on A Winter Away from Home, but predictably the sales were negligible, reviews non-existent, and it was only saved from ignominious failure by the success of a Dutch translation.

Now, having felt impelled to add my own commentary at book length on some aspects of the same publishing company that my father and my cousin had already written about, I well realise that this could be regarded as a non-commercial indulgence. I return, therefore, to my reason for writing something that may be of little interest to most readers. It is, perhaps, an exaggeration to relate the decline and fall of a publishing company that had for three-quarters of a century been a focus for intellectual and literary quality in English to the sack of a city; but for me at any rate, as a concerned witness, the catharsis of writing may, in Ford’s words, serve to get the sight out of my head.

CHAPTER ONE

John Ruskin and George Allen

My father never knew George Allen nor, as far as I know, did he meet Allen’s children, William, Hugh and Grace, who succeeded him. When he bought their bankrupt business in 1914 and added his name to the company, Stanley Unwin dealt only with the Receiver and the debenture-holders. Indeed, William Allen, my father’s predecessor as Chairman, refused to attend the final meeting of the old company as he disapproved of the sale. It would, perhaps, have been more accurate to have called the firm George Allen or Unwin, especially as the advent of war and a new owner signalled radical changes in the nature of publishing and the character of the publisher. All the same, the roots of an imprint seem to me important, and, although my father could claim no direct link with the Allens except as successor in title to the firm, my mother’s family, the Severns, did exercise a strong, perhaps even baneful, influence on George Allen through a shared connection with John Ruskin.

But after George Allen’s time, the firm’s links with Ruskin became extremely tenuous. My father claimed, probably without foundation, to have inherited Ruskin’s Literary Trusteeship from Allen, and I in my turn also claimed to have inherited it. It was neither an arduous nor a profitable duty, but it provided a strand of continuity with the past. Our catalogues too, more than fifty years after Ruskin’s death, listed in all their complexities the bindings and editions of the whole 2range of his strangely-titled books. It was stock that had survived two world wars and lain, unwrapped and drab with dust, in small piles waiting in vain for purchasers. And there were some human links too to remind us of our first footings. Not only a few grave and elderly men who had worked for the firm since the turn of the century, but the writer of a hand-written script that I discovered in the daily pile of unsolicited manuscripts within a year or two of starting work.

Her name was Kathleen Olander, and she had copied out with her own brief commentary the letters that Ruskin had written to her when she was a young and earnest art student; and he, with the urgency of old age and the storm-clouds of mental illness gathering to engulf him, found in her an icon - an image of his lost Rose - and had proposed marriage to her. Her parents intervened. The friendship was broken off, and his compromising letters were confiscated, only to be returned to her prospective husband many years later, after Ruskin’s death. But she never forgot her first love; and when, having persuaded my father that the story deserved publication, I called on her - an elderly widow in a cottage in Penn - to offer my services as editor, she agreed, but only after asking me, ‘You do believe in Mr Ruskin, don’t you?’

I never pledged my allegiance, nor felt such a close affinity to George Allen; not, at least, until the 1970s when a descendant contacted us and offered a large portrait of him by Fred Yates - too big to fit in a small house. We bought it, and hung it as a complement to Kokoschka’s picture of Sir Stanley. The contrast was remarkable. My father was alert, vibrant, engulfed in colour, and perched on the edge of his seat like a small hawk waiting to pounce. George Allen, full-bearded, melancholy and staidly-dressed sat half-slumped in the curve of his chair. It was not the face of a confident man.

But I liked having him back with us, especially as I had done his memory a disservice earlier on. In the early 1950s, when I was new to publishing, I busied myself in an area no one else had interfered with for decades - the basement cellars of 40 Museum Street. Sorting through the accumulated lumber was not a romantic occupation: the numerous small rooms were filthy, ill-lit and unloved. But as a new broom, I thought I should sweep clean. Amongst the discarded and often derelict items of office furniture there was a small, plain table, its wooden surface scarred by repeated cuts. One side had been 3cut away in a shallow crescent. I paid it small attention, but added it to the pile of broken typists’ chairs and old filing cabinets that was destined for the scrap-heap. Later I learnt that it had been George Allen’s engraving table, and the curve had been cut out so that he could position himself immediately over the plate and, at the same time, accommodate his expanding stomach.

George Allen had been an engraver long before he became a publisher, and before that he had served a four-year apprenticeship as a joiner. In 1854, when he was 22 years old, he enrolled for the Thursday evening classes at the Working Men’s College in Red Lion Square as a student of drawing, where he received instruction from both Ruskin and Rossetti. He displayed a natural talent as a craftsman and copyist rather than as an original artist, which pleased Ruskin who saw to it that he was taught engraving. Within three years he had become not just a student but an indispensable assistant, wholly employed by Ruskin on a diversity of tasks ranging from engraving his master’s book-illustrations to the immense job of sorting, mounting and cataloguing the nineteen thousand drawings and sketches contained in the Turner bequest.

Working with Ruskin inevitably brought Allen in touch with the great man’s household and, in 1856, he married Hannah, Ruskin’s mother’s maid. Those who fell under Ruskin’s spell as Allen did learnt to accept his autocratic manner, his didacticism, his insistence on total commitment to whatever task he had in hand; and their dedicated subservience was rewarded by a warmth and charm that could be irresistible. When Ruskin travelled abroad, which he did frequently, he needed the company of trusted friends and servants. In the early 1860s first Allen, then his wife and young family, were summoned to Mornex, near Geneva, where Ruskin had based himself and was working on a multitude of projects in order, perhaps, to distance himself from the conflicting emotional pressures of his life at home. In walks around Mornex, Allen was instructed in geology, another of Ruskin’s passions, and the collection of rocks and crystals that he began to accumulate were later to be stored in a massive mahogany cabinet of curiosities, that he probably constructed himself, laid out in the same manner that Ruskin himself used for his own collection. Allen’s cabinet, without the minerals, had become an immovable part of the furniture of 40 Museum Street in my time. It had been altered to 4accommodate a safe (the key for which had long been lost), and the top was used to stack manuscripts; but the range of shallow drawers with many divisions were not very adaptable to any publishing purpose.

Except as an engraver it was not until 1871 that George Allen became in any way involved with Ruskin’s books, and a better date for his true independence as a publisher would be the new, profit-sharing arrangement that Ruskin extended to Allen in 1886. But to understand how George Allen drifted into publishing at all it is necessary to look back at Ruskin’s own early involvement with books and the book-trade.

Up to his death in 1864 Ruskin’s father had idolised and indulged his only child. After John Murray had declined to publish the first volume of Modern Painters it was Ruskin’s father who, in 1843, persuaded George Smith, his neighbour at Herne Hill, to undertake this book and all subsequent books written by his talented son. George Smith, a partner in the well-established firm of Smith Elder, did so the more willingly because Ruskin’s father was prepared to have the books published on commission, and to endow his son’s publications lavishly. No expense was spared on the setting, on the engraved illustrations and on the binding. The books were published at a high price and to a high standard; they were much read and well regarded amongst cultivated people. Nevertheless, because of his father’s total intervention on the business side, Ruskin was protected from any realisation of the relationship between cost and earnings. If his interests had not widened from art history into more controversial fields of social, economic and political thought this might not have mattered. Shielded by his father’s indulgence Ruskin and his publisher might have continued a gentlemanly relationship, not unusual during the first half of the nineteenth century, based on friendship and conservatism rather than profit and ideals. But both George Smith and Ruskin’s father were horrified at the radical new directions that John Ruskin’s social conscience began to explore. In 1860 Smith put pressure on Thackeray, the editor of the The Cornhill Magazine, to suppress Unto This Last which was appearing serially; and Ruskin’s father, a year or two later, reacted with indignant opposition to Munera Pulveris. It was bad enough, in his opinion, that his brilliant son had abandoned poetry in favour of art criticism, but it was intolerable that he should now descend to challenging the moral and 5intellectual structure of society in his writings. But Ruskin was over forty years old and had become widely respected as a social critic. His father’s censorious and overbearing interventions were becoming increasingly unacceptable. ‘If he loved me less, and believed in me more, we should get on’, he wrote.

After his father’s death Ruskin was relieved of the frustration of not being able to publish what he wanted in the way he wanted it. In George Smith’s words he ‘took rather erratic views in respect to the publication of his works. He wanted to apply the principles of his social economy to them’. He had inherited his father’s not-inconsiderable wealth which, over the years, he dispensed generously though not always advisedly. Until his last years his literary earnings were not his principal source of livelihood. Yet they were substantial enough to be used as a stake by which he could endeavour to translate his analysis of the social injustice of trade into a practical challenge. In this idealistic struggle George Allen was destined to play an important part.

The book-trade in the second half of the nineteenth century was notable for technological advances in the manufacturing processes, and uncontrolled, self-defeating discounting by retailers. There are, for those who believe in business cycles, curious similarities to the conflicting pressures that afflict the book-trade at the end of the present century. The mechanisation of book-printing processes was spreading fast: steam power was most common but gas and electricity were also used. My own family’s printing business, Unwin Brothers, was the first (and perhaps also the last) to use water power for its new printing works at Woking in 1871. Other innovations included the introduction of esparto grass as a cheap but acceptable substitute for rags in paper-making, the invention of stereotyping both for illustrations and text, and the slow but inexorable mechanisation of typesetting and the binding processes. Books which had, for the most part, been elegantly produced for a restricted market during the first half of the century, could now be fashioned to respond to the widespread growth of literacy and the quest for knowledge and education at an affordable price.

But publishers’ prices remained high for most of the century. They commonly gave discounts of 33⅓% to booksellers, who used their margins to compete with each other by cutting prices to their customers. Publishers threatened boycotts but lacked any collective 6powers of enforcement. Booksellers, far from prospering, were driven to bankruptcy, and few could support themselves on the sale of books alone. It was an ineffectual trade that seemed, until the very end of the century, unable to respond to the needs of a radically-changing market. Unfortunately these price wars of the mid-century became confused in many minds with the prevailing arguments about Free Trade. It was in this context that the attempts made by some publishers and booksellers to control the anarchy of the retail trade was interpreted. Carlyle stated that he was for ‘absolute ‘Free-trade’ in all branches of book selling and book publishing’, and Gladstone declared that the state of the bookselling trade as it then existed was a disgrace to civilisation.

In this highly politicised atmosphere the Booksellers’ Association, supported by a few individual publishers, submitted a notorious case of price-cutting to arbitration in 1852. Lord Campbell’s conclusion was that any attempt at regulation would be contrary to the freedom that ought to prevail in commercial transactions. In the light of this verdict the Booksellers’ Association dissolved itself, and underselling continued to prosper until, towards the end of the century, the two sides of the trade succeeded in binding themselves into a system that protected their separate interests - the Net Book Agreement.

To Ruskin, newly fired by social concerns, the greed of the middleman was intolerable. In 1865 he wrote, ‘I have no idea of business in which my 3s 6d book is allowed to sell over the counter in retail for 2s 10d… I think it is very shameful.’ Strangely, and some would say inconsistently, however, Ruskin was not in favour of making books cheap. His quarrel was with the booksellers’ profit margins. All his early books of art criticism, which his father had underwritten and Smith Elder had published, were produced to luxurious standards, and throughout his life Ruskin argued against cheap editions for fear of jeopardising the quality of the product. He spoke publicly and gracelessly against cheap books, and referred to ‘the mischief of cheap literature’. Ruskin’s overwhelming desire to propound remedies for the human miseries and the social inequalities that he saw around him sits uneasily with his hectoring defence of book prices that were quite evidently beyond the reach of the working men of England. He considered that ‘authors ought not to be too proud to sell their own books, any more than painters to sell their own pictures’. But only 7at the price that the author thought best for his customers. He was unmoved by the fact that books might be sold to a wider readership at a lower cost, but angered by the concealed profit from which middlemen benefited every time a published book was sold to an individual purchaser. At first he believed that his publisher should supply the retail trade at a fixed price and leave the bookseller openly to add whatever margin he needed. Not surprisingly he could persuade neither publishers nor booksellers of the virtue of this system. Yet Ruskin’s social and economic convictions increasingly demanded practical outlets. It was not enough to exhort the workmen employed on the Oxford Museum to regard their labour as a ‘fraternity of toil’, he needed to match this vision by recruiting students to repair a road on the outskirts of the town. Likewise, in order to speak directly to the ‘workmen and labourers of Great Britain’ he needed a radical new method of disseminating his ideas.

So it was that in 1871, without prior warning, a parcel arrived at George Allen’s small cottage in Keston in Kent containing copies of the first monthly issue of Fors Clavigera, that Smith Elder had had printed, and Ruskin wished George Allen to sell on his behalf. In this manner George Allen became a publisher.

Ruskin conceived of Fors as a series of letters through which he could speak directly to a wide, working-class public about everyday concerns that reflected the problems and iniquities that he perceived in society, matched with the solutions that he propounded. He wrote as a didact, but he appealed to a readership that was anxious to learn and accepted authority. The price of each issue was 10d - a not inconsiderable amount - but Ruskin was unrepentant. ‘I don’t want any poor people to read my books… I want them to read these letters, which they can get, each for the price of two pots of beer: and not to read my large books, nor anybody else’s, till they are rich enough, at least, to pay for good printing and binding.’ How the 10d was actually divided Ruskin took pains to explain, but the scale of distribution must have been fairly modest or Allen’s cottage industry would have been swamped. Allen claimed that he never lost money in those early days, and the gradual process throughout the 1870s, during which he took over Ruskin’s publications, at least gave him time to learn his new trade. But it was Ruskin who told him what he should publish and how he should sell down to the minutest detail. ‘My dear Allen’, 8he wrote on one occasion, ‘you really are a considerable goose. Of course you musn’t take booksellers’ orders for less than a dozen - and they must pay their own carriage.’

Smith Elder continued to produce Fors until 1873, and it was not until 1878 that Ruskin, who because of his commission agreements owned his copyrights and stock, instructed Allen to pay Smith Elder five hundred guineas and take over complete responsibility for all his publications. George Smith’s view was philosophic. ‘Ruskin removed his books from my firm for a reason which seems to me to show that publishers suffer occasionally because authors are bad businessmen.’

Meanwhile, in 1874, because his cottage was too small, George Allen borrowed £500 from Ruskin to buy a two acre site in Orpington on which he built a house called Sunnyside. It was from this address that Allen started to publish under his own name. To Ruskin this had the added attraction of fulfilling another of his visions - the decentralisation of industry. For the same reason changing to Hazell, Watson & Viney as his main printer came about, not because of the innovation of having electric motors to drive their flat-bed machines, but because they had left London for a green-field site at Aylesbury.

Publishing according to Ruskinian principles did not prove easy. It would be ingenuous to believe that booksellers and prospective readers, who were publicly and (as mental instability increased) shrilly rebuked by Ruskin, would forgive and forget when his publisher tried to persuade them to buy his books. In 1879 Allen reported to Ruskin of ‘a booksellers’ meeting where they groaned at you’, and the following year the Manchester Ruskin Society, which should have been well disposed, issued a pamphlet entitled, ‘Is it true that Mr Ruskin’s books are scarce, dear and difficult to obtain?’.

The pricing and printing history of Sesame and Lilies, probably Ruskin’s most successful book, reflects the problems under which Allen laboured. It was first published in 1865 at 3s 6d and had sold 4,000 copies when Allen took over. At Ruskin’s instigation it was then reprinted as the first of a new, collected edition at double the price, initially without any discount to booksellers. As sales declined the price was increased, and although Allen did persuade Ruskin to allow some trade discount, the price had reached 18s by 1874. There were two small reprints in 1876 and 1880, but it was not until 1882, when Allen was beginning to free himself of some of his shackles, 9that the title appeared as one of a new 5s series. In this format it was regularly reprinted until, by 1899, it was selling 12,000 copies a year. But only after Ruskin’s death did Allen venture to produce a truly cheap, ‘Pocket Edition’ at 1s 6d. Sesame and Lilies, incidentally, was the only title by Ruskin that still sold in any noticeable quantity when I arrived in publishing, and most of them went to India.

Power and control shifted during the 1880s. Ruskin, with increasingly frequent attacks of mental instability, had burnt himself out. Allen, having served his apprenticeship as a publisher under the erratic direction of his master, was now often obliged to take decisions that were prompted by commercial rather than idealistic considerations. Sometimes Ruskin could be persuaded to shift his ground. In 1882 the running quarrel with the booksellers was overcome. A small, fixed discount of 10% was to be allowed off a fixed published price. This proved broadly acceptable, though Allen was kept busy ensuring that there was no price-cutting. In effect his terms, and his determination to monitor them, anticipated the Net Book Agreement of 1899. Even more important to Allen was the new agreement that Ruskin was persuaded to enter into in 1886. Hitherto George Allen had been paid a commission on sales. Now he was to share with Ruskin under a proportionate profits system, that allowed him security to build up and diversify the firm on his own account despite Ruskin’s increasingly remote involvement.

All the same, Allen still found it difficult to act with complete independence. Sometimes Ruskin would overwhelm him with gratitude. ‘How good and kind you are, and have always been,’ he wrote on one occasion, ‘I trust, whatever happens to me, that your position, with the copyrights of my books - if anybody cares for them - and with the friends gained by your honesty and industry is secure on your little piece of Kentish home territory.’ But he could be totally unreasonable too. Baxter, Ruskin’s Irish manservant who accompanied him on his travels, wrote from Paris in 1888 that his master had ‘given it to Allen something awful - read it all over to me - a sheet of foolscap. I think if Mr Allen ever had any doubts about his sanity they will be removed now.’ Over the years Allen had, like Baxter, learnt how to handle Ruskin, and what he strove to achieve for his firm now was increasingly at variance with the economic principles adumbrated in Fors. Sometimes by persuasion but often without 10referring to Brantwood, where all change tended to be mistrusted and deplored, he modelled his Company so that it became fairly similar to other small, late-Victorian publishing houses. Except in one respect: it published the works of only one author. At about the time of the new agreement Allen was obliged to build a publishing shed behind his house in Orpington to accommodate the increasing number of books. At that time there were in fact 63 different works or editions, and most of them were stocked in various styles of binding. When Ruskin came on one of his last visits to inspect the new warehouse Allen ‘tried to get him to come and help; but he was quite frightened at the parcels, and refused to believe that anybody really wanted to buy his books.’

The new agreement, in all probability, lay at the heart of the intermittent hostility that flared between George Allen and Joan Severn, who looked after her elderly cousin and protected him from all intrusion as he sat in increasing silence in his chair overlooking Coniston Water. Even Allen, when he was still able to call in the early 1890s, was never trusted to be left alone with his master and friend of forty years, but ‘the old dragon sat opposite and never budged an inch.’ Worst of all Joan Severn felt herself obliged to defend those uncommercial public utterances of business principles that her cousin had made many years ago and was now incapable of amending. The 1886 partnership agreement had given Allen some liberty of action in respect of Ruskin’s publications. Joan Severn suspected that he used this for his own advantage. But increasingly she needed the profits that Ruskin’s books produced as the only income available for the care of her cousin, the upkeep of Brantwood and of the house at Herne Hill. Her husband, Arthur Severn, was an artist and his own earnings were uncertain. However, she never allowed herself to make common cause with Allen, who, during Ruskin’s last decade, did make some genuine attempts to re-invigorate sales that had declined, though often by methods that Brantwood regarded as heretical.

Ruskin had disapproved of all forms of advertising and the sending of books out for review: Allen quietly reversed this policy. Ruskin hated the centralisation of commerce in London: in 1890 Allen rented offices at 8 Bell Yard, near Temple Bar. Ruskin hated cheap books: Allen initiated the 5s green octavo reprints that eventually included all Ruskin’s major books, including for the first 11time, affordable editions of his early books of art criticism with the engravings decently reproduced.

As a result of these initiatives the sale of Ruskin’s books and the appreciation of his achievements reached their highest levels during the decade of his enforced silence; and Allen was able to pay £3-4,000 each year to his old master and partner as his share of the profits - a not inconsiderable sum. Allen, we must presume, was retaining an equal profit himself, and by 1890 he felt sufficient confidence in the progress of the firm that bore his name to take another step towards independence from Brantwood: he bought in the complete works of Augustus Hare, the popular travel writer and memorialist, and soon after began to publish the first translations of Maeterlinck and books by other authors quite unrelated to Ruskin.

For many reasons it was prudent to take such steps. The supply of original new books by Ruskin had dried up just as his popularity was at its peak. The demand for new product could, in part, be filled by somewhat vapid compilations of elegant extracts from existing books. These small anthologies - Bible references, Birthday books, Ruskin on Music, and so on - picked out aphorisms and purple passages rather than the central arguments of the original works, but they catered for the sensibilities of the age. Rather less successful, but preferable in Allen’s eyes, were a number of lavish, slow-selling, heavily-illustrated and expensive books that Allen originated. They were the coffee-table books of the period, and Allen loved them because they allowed him to use his old skills as a book-maker. The various elaborate bindings, the blocking, the paper and the engravings were in the style of a past age: the contents, often compiled from past lectures or essays, harked back to Ruskin’s early books of art criticism, but they lacked their intellectual rigour. Ruskin and Turner, Verona and its Rivers,The Oxford Museum were in this style: their cost of production was horrifyingly high, and it is doubtful if there were enough sales to justify the expense that Allen lavished upon them. ‘People don’t like large sized books in these days somehow,’ he lamented, ‘the fashion has changed.’ But he continued publishing them just the same.

George Allen’s publishing in the 1890s was a strange mixture of the shrewd enterprise of a tradesman (which sometimes had to be modified in deference to Brantwood’s susceptibilities), and an unimaginative reluctance to extend into new ventures substantially 12different in style from what he had been trained to do in the past. He never commissioned any independent commercial successes that could match the sales of the cheap 8vo reprints of Ruskin’s standard works. The market he knew and tried to cultivate comprised connoisseurs and collectors, the books he chose to publish tended to be memoirs or illustrated classics, and it was the illustrator rather than the text that most attracted him. Most of his books were worthy, over-produced and dull. In 1896, apart from Ruskin and Hare, George Allen’s catalogue listed 24 new titles, 15 of which were illustrated books. It was not until 1899 that he ventured to publish his first novel and a book of poetry, but he never followed up such innovations convincingly. He was innately cautious and indecisive about the contents of his books. At about this time he tried to relaunch the literary magazine Argosy, but neither he nor his children (who worked with him in the expanding business) had any great feel for modern literature. They were production trained, and instead of leading the market they yearned towards a type of publishing that was dated and out of demand.

Within three years of opening his small offices in Bell Yard Allen came to the conclusion that he needed larger premises, and that the advantages of London for his headquarters outweighed the Ruskinian dream of decentralisation in rural Kent. But before he was able to rent his prestigious new premises at 156 Charing Cross Road he had to tackle the reluctance of Brantwood. This hurdle overcome, George Allen was at pains to make every detail of the refurbished building reflect the Ruskinian ethos. He commissioned a wrought-iron hanging sign, and a colophon for his books (reproduced on the title-page of this one) from Walter Crane, both of which continued to be used, with the additional name when it was incorporated, throughout the company’s life; he chose Deucalion, the title of one of Ruskin’s books, as his telegraphic address; he hung portraits of Ruskin in youth and in age in the reception rooms, and displayed engravings by Lupton and by himself based on Ruskin’s own sketches, together with a library of Ruskin editions in his own sanctum. Every room seemed to have a Ruskin relic, and the building itself was called Ruskin House. The name stood out boldly in gold on Crane’s black metal sign, but it only lasted 15 years in the Charing Cross Road. Thereafter, wherever the sign lodged, it named the building. 13

It was hung longest on 40 Museum Street, carrying the name even though the last of Ruskin’s books had vanished from his publisher’s lists; and now, a century after it was first displayed, his publisher too has disappeared. But the sign still hangs there, and the building still bears Ruskin’s name.

The years following the move to Charing Cross Road saw Allen at the height of his career. He was recognised amongst his peers as a well-established publisher, and he acted with autocratic confidence in his business dealings. He hired his first reader (though the final judgements on what to publish remained firmly in his own hands) and his first travelling salesmen. Their existence marked another change in marketing practice. The trade sale dinners that most publishers used to hold were dying out. They involved wining and dining the major booksellers, and at the end of the meal, when resistance was lowered, the auctioning of new titles (and remainders) to the assembled guests. The new travelling salesmen did not just take orders, they were itinerant debt-collectors, and they explained Allen’s trade terms - still unorthodox, but modified since his move to London to allow 15%, carriage forward, to the booksellers. Amongst the new staff that Allen confidently employed at this time was a young warehouseman, George Speed, who stayed on through all the company’s vicissitudes for 55 years, a legendary character with a wealth of dogmatic opinions who finally retired in 1948.

But despite new staff and new premises Allen, as he had been trained to do, attended to every detail of the business himself. He wrote in his own hand to the office boy’s parents asking them to get their son up earlier in the morning; he ordered the new coal-scuttle that he needed for his office. He worked hard, and was demanding of others. The perfectionism of a craftsman was in his blood, and delegation did not come naturally to him. He was not brusque and overbearing in an assertive, bullying way; it seemed more like the exasperation of a man stretched by an intolerable burden of overwork. One suspects that he had been happier as the loyal and skilled tradesman, unflustered by his appreciative master, than as head of a turbulent commercial enterprise. He found solace in many things; in tending his bees in Orpington, in his growing collection of Martinware pottery (a few specimens of which - like George Speed - stayed with the firm), and in sampling a case of wine that his brother had shipped to him from 14South Australia. But petulance creeps all too often into his business correspondence. He was, perhaps, less secure and confident than he seemed, despite having launched himself as an independent publisher into the London book world. For only he knew how illusory his independence really was. He scarcely made money on his new publications, and fretted more about his overheads than about the contents and style of the books themselves. His devotion to Ruskin never wavered, but it was the Ruskin of his youth, not the present guardians, to whom he felt loyalty. And he himself was ageing and felt out of sympathy with many aspects of the changing world. Besides, he realised that Ruskin might die at any time and his copyrights would only endure for seven years after his death.

Allen knew that in America, where Ruskin’s books were virtually unprotected, piracy was rife and in consequence it had proved almost impossible to sell either books or rights. This was nothing new. Long before, Ruskin had remarked, ‘if there had been international copyright between England and America, I should have been a man of very large fortune’. But because of Ruskin’s insistence on high standards and high prices, and his refusal to allow sheet run-ons on cheap paper to be sold inexpensively as ‘colonial’ editions, the pirates had cornered the market.

By 1895 there were over 100 unauthorised editions on the market. Allen endeavoured to sell ‘authorised’ copies through the US publisher Merrill and Co., to whom he gave an unprecedented discount of 33⅓%, but even so they could not match the pirates’ prices. Latterly Allen must have realised that when Ruskin’s copyrights expired the home market too would be flooded with cheap reprints against which, under Brantwood’s rules, he could never compete. The real profit of his company still came from Ruskin’s standard works: remove those sales and there was little hope of the firm prospering. And all Allen’s hard-won achievements, his improved social position, his family’s future, and any dignity in his old age, might vanish in seven years’ time. George Allen had every reason to be a worried man.

Ruskin died before the new century was a month old, and the quarrels, half-suppressed during his lifetime, surfaced more openly between Joan Severn, the principal executrix, and George Allen. Ruskin’s will made clear that all further editions of his work should be published by Allen and his heirs or successors; but under the existing 151842 Copyright Act most of the books would fall into the public domain in 1907, so the time available to market them exclusively was very limited. But Allen tried. He produced 1/6d paperback editions of some of the popular books, and reversed another of Ruskin’s prohibitions by licensing over twenty translations during the early years of the century, especially in France and Germany, as Ruskin’s works were much discussed but not easily accessible in those countries.

The most impressive project that he undertook, in collaboration with another of Ruskin’s executors, Alexander Wedderburn, and perhaps the most abiding achievement of his publishing career, was the Library Edition of Ruskin’s works in 39 volumes. He had conceived the idea some years earlier: a definitive and substantial monument, produced to the highest specifications, and made economically possible by re-using many of the carefully-stored old plates, many of which he had engraved himself. Alexander Wedderburn and E. T. Cook, the joint editors, were old and trusted friends of Ruskin to whom Joan Severn could not object. She and her American confidant, Charles Eliot Norton, another friend of Ruskin in his old age to whom Joan constantly turned for support and confirmation of her many suspicions, were uneasy at what appeared to be their loss of control.

The project was presented to her as a final, costed package. Originally it had been conceived as thirty volumes, and two thousand sets were to be printed at £1 per volume. If they all sold, this would have realised £60,000. Roughly half this amount would cover the costs and the rest would be split equally between the publisher, the editors and the Brantwood Fund - a trust that had been set up in an attempt to preserve the house, its contents, its staff and the Severns exactly in the manner that Ruskin had left them. Joan Severn thought that Wedderburn (and perhaps also Allen) had claimed too large a share: but she argued in vain, and grudgingly - because she and the Brantwood Fund needed the money - agreed to the division. The first volume appeared in 1903, and the project was not finally completed until 1911, though Allen saw most of the volumes through the press in his own lifetime.

Another cause for dispute between Joan Severn and George Allen concerned the ownership of Ruskin’s manuscripts. Under his will Ruskin left these to Joan, but many of them Allen already 16possessed and claimed that Ruskin had given them to him. Indeed he produced a letter to prove that Ruskin had presented him with at least two. On legal advice Joan was advised not to press her claim, but she must have felt that her suspicions about Allen’s conduct had been confirmed, especially after she heard that he had sold several of these manuscripts to America for noticeably high prices: The Seven Lamps of Architecture fetched £1,000 and Modern Paintings £5,000.

The early years of the century were encouraging for the British book trade. The net book system had begun to stabilise the retail trade, the Elementary Education Act of 1870 and the consequent decline of illiteracy had resulted in a vast number of new books being published. Not only text books, but cheap, informative books to feed the new hunger for knowledge. In 1901 over 6,000 titles were produced - sixteen times the number that had appeared at the beginning of the previous century.

Ruskin still dominated George Allen’s publishing, but his list did include a few authors whose books sold well, and continued to be read throughout the century. Maeterlinck’s Life of the Bee delighted Allen, himself a keen apiarist, and sold some 200,000 copies over the years. Equally successful was Hilaire Belloc’s Path to Rome. Both these titles were still selling, and occasionally being reprinted, when I became a publisher over 50 years later.

Another author who joined the list in 1900, and whose long list of books eventually became my charge, was Gilbert Murray. The first of his verse translations from the Greek, Andromache, was followed by many others. They gave a rhythmical, romantic interpretation of tragedy that became the accepted versions of these classic plays throughout the first half of the twentieth century. Today other translations have taken over and Murray’s seem hopelessly dated, but for many they bridged the educational divide between the tiny minority who could read the Greek originals and the new breed of English-literate students with imperfect classical education.

Murray did not have a happy time towards the end of George Allen & Co’s independent existence. Royalties were not being paid and he confessed that he felt uneasy at being sold like part of the furniture when the Receiver accepted my father’s offer for the firm. But things quickly changed. He and my father established a very real friendship and respect that lasted throughout their long lives. 17

I met him but once when I was invited to call on him at Boars Hill to discuss some small problem concerning his books. He was old and frail, but mentally alert and possessed of the same gentle but insistent courtesy to which my father had often referred. We did our business walking underneath the huge rhododendrons in his garden and returned to the house for tea. His wife, Lady Mary Murray, I had been warned was now senile, but she presided over the tea-table with dangerous aplomb. She poured the first cup but would not let me have it to pass on to her husband. There was an awkward deadlock until Murray quietly got up and took the cup himself. The next cup was for me. Lady Mary poured, but the cup had overflowed into the saucer before she stopped. For a moment she was puzzled, but then solved the problem by carefully lifting the brimming cup and pouring the contents of the saucer into it. Not an easy meal, but Murray, more used to it than I, was kind and calm. To digress even further I remember another difficult tea on Boars Hill with the elderly John Masefield. I had a slice of bread and butter on my plate and Masefield, who had largely ignored me hitherto, pushed a covered jar over to me, saying with a conspiratorial leer, ‘have some honey’. I thanked him and removed the lid. It was quite empty.

In 1907, as anticipated, most of Ruskin’s works fell out of copyright, and ever-cheaper editions of the most popular books started to appear. George Allen, now in his 75th year, chafed and disputed but to little avail. He published an account of his attempts to control the flood, Copyright and Copy-wrong, but he could not turn the clock back. Indeed, in the autumn of this same year he died, leaving the firm to his three children. They deserve some sympathy. They had grown up to understand a style of publishing that was inappropriate to the evolving market place. The secure sales of Ruskin’s books had masked the unprofitability of the rest of the list. Now, with Ruskin no longer in copyright, they were still faced with the high overheads of Charing Cross Road, no instinctive talent for finding saleable authors, and the assumption - understandable when unquestioning children inherit a business from an autocratic and elderly parent - that it was only necessary to carry on as before.

It was not long, however, before they were obliged to take more positive steps to save the company. In 1909 they bought the publishing side of the printers, Bemrose of Derby, paying for it by long-dated 18bills. It was an extremely utilitarian list, the highlights of which were a variety of church stationery and notices, used by a few parishes even into the 1950s, and Balance Time Interest Tables - which were killed by the pocket calculator. These additions to the list hardly added to the character of the firm, and the manner of payment only deferred George Allen & Co’s problems. At the same time the company was moved from Charing Cross Road into smaller premises nearby at 44/5 Rathbone Place, just off Oxford Street. Because of the move, many of George Allen’s personal treasures were put up for sale - a sad little auction of books, Martinware pottery and pictures, some by, or given by, Ruskin that had been assembled 15 years previously to grace the new London offices, but now were not expected to fetch much more than £1,500.

Inexorably the company’s decline continued. As the Bemrose bills fell due there was still no improvement in the cash position. The only quick way to raise money was by another amalgamation and, as is usually the case, the only prospective candidates were in trouble themselves. In 1911 a new merger was announced, this time with a publisher of greater distinction, Swan Sonnenschein.

But both owners were deceiving themselves in believing that strength lay in unity. For the past quarter-century both firms had survived and even prospered, each driven by its founder on a highly individual and totally distinct course. In neither business could the successors maintain the original creative impetus. They sought shelter as a substitute for a publishing policy.

Early in the new century William Swan Sonnenschein, who had founded his imprint as a young man in 1878, deserted the company in order to take up the challenge of restoring the fortunes of George Routledge and Sons. Probably he did not intend wholly to abandon his old firm, but the drift became inexorable. Herbert Wigram and Colonel Dalbiac, gentlemen with, respectively, Indian civil service and army backgrounds, who had joined Sonnenschein as partners, now acquired control over a business that was far more fragile than the intellectual quality of its list would suggest. Its average turnover in the years prior to amalgamation only amounted to some fourteen thousand pounds, yet this was a list of considerably more substance than that of George Allen. There were books by Shaw, Barrie and George Moore: the first English translations of Freud, Marx and 19Schopenhauer: Muirhead’s Library of Philosophy and a Social Science Series, both of which series contained seminal works far in advance of their times. William Swan Sonnenschein, with his European background and his gift for detecting works of serious academic purpose in a wide range of subjects, was a brilliant acquisition editor, even though the enduring quality of his choices were seldom immediately apparent, and despite their small contributions to his profits. Undoubtedly more Swan Sonnenschein titles were being sold fifty or sixty years after he had left his company than were sold during the years when he was creating it. The backlist that my father eventually acquired, and which he proudly cherished throughout his publishing life, owed far more to Sonnenschein than to Allen. Nevertheless, when the merger terms had been agreed, it was Allen’s name that survived with Wigram and Dalbiac being brought in as substantial debenture holders and the status of Directors. William Allen had once again staved off collapse at the cost of a burdensome debt and a top-heavy management structure.

The search for working capital dominated the next year or two. From the surviving letter-books it would seem that William Allen spent much of his time dealing with creditors, and endeavouring to persuade investors to support the failing company. Only one investor of any size did in fact join, and became a Director in return for a debenture. E. L. Skinner was to be a thorn in my father’s side until the mid-thirties when he was eventually persuaded to take over Williams and Norgate, which my father had just acquired, and finally to resign from George Allen & Unwin.

Two years after the merger with Swan Sonnenschein and despite the move to cheaper premises, William Allen was in trouble again. The hoped-for economies of scale had not materialised and the debenture holders, alarmed at the threat to their investment, called in the Receiver. The rest of the story will be familiar to readers of The Truth about a Publisher.