18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

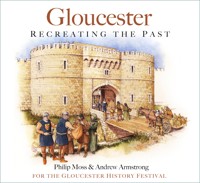

If you stand today in the middle of Gloucester you're standing above two thousand years of accumulated history. Beneath your feet is a Roman fortress, a proud colonial city, a Saxon royal centre, a prosperous medieval market town, a Roundhead bastion and an expanding Victorian industrial hub. Over the last 50 years, local artist and historian Philip Moss has been recreating those Gloucesters of the past in a series of beautiful and well researched reconstruction drawings and paintings. In Gloucester: Recreating the Past, the complete body of Philip's work has been collected together for the first time, and is presented alongside original photographs and drawings from archaeological excavations to tell the story of Gloucester from its Roman beginnings to the present day.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

First published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Philip Moss & Andrew Armstrong, 2021

The right of Philip Moss & Andrew Armstrong to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9825 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Europe

Contents

About the Authors

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Beginnings

The New Fortress

Colonia

Holes into the Past

Return to the Bon Marché

The Forum

Stonework in Southgate Street

Westgate Colonnade

The Walls

The Gates

The Waterfront

Outside the Walls

Amphitheatre

Roman Glevum to Saxon Gloucester

Invasion

The Old Castle

The New Castle

The East Gate and Kings Walk Bastion

The Medieval Bridges

Medieval Gloucester

Normal Life

Tanners’ Hall

Later Use of the City Gates

Hidden Gems?

The Siege of Gloucester, 1643

Gloucester, 1750

Creating the Future?

About the Authors

PHILIP MOSS was born in Gloucester and educated at the Crypt Grammar School. He studied technical illustration at the Gloucester College of Art and the Royal West of England Academy of Art at Bristol. He worked in technical publications in the aviation and construction equipment industries, and later as a freelance illustrator and designer. He was involved in many projects in engineering, architecture and also archaeology with the recording and publication of many sites, not only locally but also of Carthage and Rome.

He was a founding member of the Gloucester and District Archaeological Research Group in 1967 and of the Gloucester Civic Trust in 1972. He was awarded the Mayor of Gloucester’s Medal in 2016 for his work in promoting the heritage of the city.

ANDREW ARMSTRONG was born in Colchester and spent his childhood moving between various army bases in Germany and England before settling in Salisbury. He graduated with a degree in archaeology from the University of York in 2000. Uncertain what to do with his life, but horrified by the concept of an office job, he tried his hand at being a ‘field archaeologist’, spending six years working on archaeological sites throughout southern England. This was followed by a brief but educational period as an archaeological consultant, and something called a ‘countryside archaeological adviser’ at Gloucestershire County Council. He joined Gloucester City Council as City Archaeologist in 2012. After nine years Andrew is starting to feel like he knows what he’s doing, which may not be a good sign.

Acknowledgements

Over the years I have had, and still have, the pleasure of working with many archaeologists and historians, notably Henry Hurst, Carolyn Heighway, John Rhodes, Malcolm Atkin, Nigel Spry, Hugh Conway-Jones, Tony Conder and Malcolm Watkins.

Thanks to my wife, Gillian, for all her help and encouragement on many archaeological projects.

All the illustrations were drawn using the known archaeological and historical information available at the time. However, as new evidence comes to light, I hope others will be moved to reinterpret the drawings featured in this book.

It has been an enjoyable and rewarding experience to work with Andrew Armstrong in the compilation of this work. His knowledge and enthusiasm are a major asset to the City of Gloucester.

Philip Moss

Many of the photographs or images reproduced in this book were kindly provided by the Museum of Gloucester. The authors are also grateful to the following for permission to reproduce images: Gloucestershire Archives, Gloucestershire County Council Archaeology Service, Avon Archaeology, Cotswold Archaeology, Henry Hurst, Cape Homes, Ted Wilson, Llanthony Secunda Priory Trust and Reach PLC. Finally, I’m very grateful to my wife Tamsen for proof-reading the drafts of this book; she has heroically filtered out my jargon-heavy text and patiently identified a number of regrettable typos – thank heavens for English Literature graduates!

Andrew Armstrong

Introduction

If you stand today at the Cross in the centre of Gloucester, you are on a man-made hill, perhaps 4 to 5m above the original ground level. Below you lie layer after layer of the city’s history. If you’d stood on the same spot nearly two thousand years ago you may well have seen the arrival of the first Roman soldiers on the edge of the Severn, or the creation of the fortress that was to become Gloucester.

The military engineers who laid out that fortress were, unknowingly, defining the layout of a city that still endures after two thousand years. Many of the roads and streets in the city today were defined by the Romans and still broadly follow their original routes. The fortress remained in use for some decades and was replaced ultimately by a newly founded Roman city. That city, called Glevum, was a ‘colonia’ – a retirement settlement for Roman soldiers. By this time (the late first century AD), the term ‘Roman’ could refer to people from a diverse range of countries and backgrounds and it is likely that this first Gloucester was populated by people from all over the Mediterranean world, as well as parts of Germany and northern France.

These early citizens adopted for their city the exact layout of the fortress from which it had grown. For around three hundred years, they raised public buildings, built town houses, prayed to various gods, died and were buried. But then their city, like the empire that had borne it, began to decline. By the sixth century it is unclear if Glevum still survived as a city. If not, it may still have been a place of importance, a site perhaps of political and religious leadership. A small population living on in the faded grandeur of Rome.

With the coming of the seventh century, Gloucester emerges from the Dark Ages back into recorded history. Minor princes, lords of the forgotten Kingdom of the Hwicce, saw fit to found a minster (the Anglo-Saxon name for a monastery) in Gloucester. These Hiwccan lords were vassals of a greater power – the Kingdom of Mercia. For a time, Mercia was the greatest English kingdom, whose hegemony extended from Kent into Wales and as far north as the Humber.

In AD 865 the Danes (Vikings, if you prefer) invaded and conquered half of England, including the north-eastern half of Mercia. Gloucester, in the south-west of Mercia, remained English. The Danish great army, led by a king called Guthrum, occupied Gloucester for some months. Somehow, Gloucester endured these disasters and emerged from the conflict with newfound importance.

Alfred the Great, King of Wessex*, was able to defeat Guthrum’s army and to stop any further Danish conquest. Consequently, at the end of the ninth century Gloucester found itself the capital city of English Mercia, ruled by a daughter of Alfred the Great – Aethelflaed. It is from Gloucester that Aethelflaed reconquered the kingdom of Mercia from the Danes. Gloucester was also childhood home to Athelstan – a monarch somewhat lost to history, who was to be the first king of all the English peoples. He died in Gloucester in AD 939. Gloucester remained a royal city in the later Saxon period and was a favoured haunt of Edward the Confessor.

After the Norman conquest of 1066, Gloucester continued to attract kings and was the place from which William the Conqueror commissioned Domesday Book, that extraordinary glimpse of the England of a thousand years ago. Although not obvious today, two castles were built in the city. The first, a timber and earth structure that lies partly beneath Blackfriars, was replaced by a more impressive stone keep and bailey on the site of what was later Gloucester prison. The Normans built prodigiously in the years after the invasion, raising the churches and monasteries that can be found throughout the city today.

Henry III was crowned in St Peter’s Abbey in Gloucester in 1216 during the turmoil of the first Barons’ War – a conflict between his father, King John, and the great lords of England. He remained fond of the city, repairing and reinforcing its walls, greatly improving the castle and endowing the various religious houses over the next sixty years. He was often in residence, as was his son, the future Edward I.

After Edward, few royals took much interest in Gloucester. Richard III granted the city’s charter of incorporation in 1483, essentially giving the citizens the right to manage their own affairs. This was in gratitude after Gloucester had closed its gates to Margaret of Anjou, the leader of Lancastrian forces seeking to reach allies in Wales. Instead, the trapped Lancastrian army faced annihilation at the battle of Tewkesbury – one of the bloodiest battles of the War of the Roses.

The attention of monarchs returned to Gloucester during the English Civil War. In 1643, after the Royalist army had defeated all other Parliamentary forces in south-west England, Charles I himself came to Gloucester. He hoped to quickly subdue the city, gather his forces and march on London and perhaps win the war. The failure of his army and his ambitions in the muddy, flooded fields around Gloucester in August and September was a major turning point of the war – from which the Royalist cause never recovered.

The story of Gloucester, a fortress city on the Severn, has, in so many ways, been the story of England. It is an extraordinary story – one that archaeologists and historians struggle to convey and to articulate in a way that does justice to achievements, events or monuments. Thank heavens then, that we have the artwork of Phil Moss to help us. Over the last forty years Phil has produced work that inspires a better and more empathetic understanding of that story. Phil’s wonderful artistic skill, combined with his real archaeological and historical knowledge, mean that he has been able to convey Gloucester’s past in a way that few people could, recreating this past in way that lets us better comprehend our history and, hopefully, better appreciate our present.

________

* A southern English kingdom – by the late ninth century it controlled all the land south of the Thames.

Beginnings

Gloucester was founded by the Romans, who landed in Kent in AD 43 and had reached the edge of the Severn by about AD 47. On their arrival, the Roman army built their first fortress – not in the city centre, but in Kingsholm, a suburb about a kilometre to the north. What attracted the Romans to Kingsholm? Well, I hear you cry – it’s a perfectly pleasant spot, nice rugby ground, good schools that sort of thing. Of course, in Roman times Kingsholm was, as far as we can tell, a slightly raised meadow next to the river and was no doubt damp and prone to flooding. It is a puzzling location for the first fortress in Gloucester, low-lying and some distance from the best river crossing.

So why did the Romans build their first fort in Kingsholm? Well, recent archaeological excavations further south in the city centre have found the remains of a late Iron Age settlement, which may have been standing when the Romans arrived. The people who lived there would have been part of a nation the Romans referred to as the ‘Dubonni’, who were allies of Rome. It is possible, therefore, that the first Roman fortress was located at Kingsholm to avoid antagonising these friendly locals.