13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

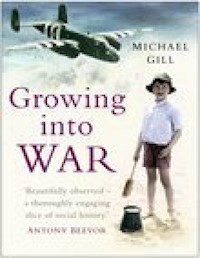

Michael Gill is widely regarded as being one of the finest documentary film-makers of the twentieth century. Working as a junior reporter, he experienced the Second World War at first hand when he and his family were bombed out of their Canterbury home in June 1942. In August that year Michael joined the RAF and swiftly encountered the incomprehensible pettiness and rule-bound incongruities of service life. Later commissioned into the RAF Intelligence Branch, he was attached to a tactical bomber squadron in the build-up to D-Day and flew as an observer on operations over the devastated Normandy countryside. As the war moved towards its awful conclusion, Michael journeyed to Holland and on into Germany with his unit, witnessing the final days of the war and its pathetic aftermath for ordinary Germans. This beautifully observed memoir of the Second World War is head and shoulders above the many other accounts by those who did not fight the war 'at the sharp end', by virtue of Michael Gill's skilfully crafted narrative and believable characterisation of the people that inhabit its pages.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2005

Ähnliche

Growing into

WAR

MICHAEL GILL

Foreword by

A.A. GILL

First published in 2005

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Michael Gill, 2005, 2013

The right of Michael Gill to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9593 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

I dedicate this book to my three children, Adrian, Nicholas and Chloe

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

Foreword by A.A. Gill

1.

Distant Relations

2.

A Friend for Life

3.

Expectations of Love

4.

‘The Navy’s Here’

5.

Regions Dolorous

6.

Cold Hands

7.

Hot News

8.

Stamping on the Hinge of Fate

9.

Hut 50

10.

Scrambling for Orders

11.

Fire on the Runway

12.

A Cottage in the Woods

Afterword by Georgina Gill: Ants on Snow

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1. Mary Gill, my mother

2. My father, George Arnold Gill

3. This is me at fourteen months being held by my nurse

4. My father relaxing in our garden

5. My mother and her younger brother Clifford

6. My mother’s parents, William and Emily Taylor

7. The wedding of Sarah Jane Taylor, my great-aunt

8. Fred and Will Taylor, my great-uncles

9. My great-grandmother Taylor, in formal pose

10. William Taylor, my grandfather

11. My grandmother, Emily Thomas Taylor

12. My grandmother Taylor (on the right) with a friend

13. Henry Talbot, my grandmother’s admirer

14. At Winchester with my grandmother

15. My grandfather, George Gill, and me

16. Out and about with my mother at Herne Bay

17. This is me at eight

18. Here I am in my spinal chair with my father, grandfather and dog Patch

19. My cousin, Carolyn Taylor

20. Stephen Coltham, my tutor, who was an important influence on me as a boy

21. No. 28 Squadron RAF, Skegness, 1942

22. Christmas Day menu, 1943

23. Jimmy Blair and me in Dublin, September 1943

24. Pilot Officer Michael Gill

25. The ops board at Hartford Bridge on D+1, 7 June 1944

26. An RAF Mitchell bomber takes off to attack a target in Northern France shortly after D-Day, 1944

27. No. 137 Wing, Hartford Bridge, 1944

28. The special fog dispersal aid ‘Fido’ in operation at an RAF bomber station

29. The King and Queen leaving the Officers’ Mess at Hartford Bridge with the station commander, Group Captain Macdonald, September 1944

30. Medal presentation parade at Hartford Bridge, September 1944

31. Enjoying a drink at a café on the Champs Elysees with Hillerby, our Met Officer

32. In the ops room at Vitry-en-Artois, near Douai, in Northern France, 1945. I’m the one with the pipe

33. A knocked-out German Tiger tank on the Vimy–Lens road. Sergeant Metcalfe, Les Rates, me, Leading Aircraftmen Boulter and Nichols, April 1945

34. Germany, 1945. I’m on the right. We both had revolvers

35. Ruined Cologne, but the cathedral survived

36. In Germany, 1946

Copyright note

The extract from Stephen Spender’s poem ‘I think continually of those who were truly great’ on p. 170 is reproduced by kind permission of Faber & Faber Ltd.

FOREWORD

My father never wrote at a desk. He always sat on the sofa and used a felt tip pen to write in longhand on a clipboard surrounded by books, larded with ripped-up paper bookmarks. A desk would have been too formal, too reminiscent of his father the bank manager. He didn’t wear suits or ties either or go in for any of the coded trappings of probity, the Establishment or the past.

He was a man who was happy to be at home in his time. He liked contemporary things, contemporary people and ideas. I never once heard him hanker for yesterday, or ever wax nostalgic. He was a man of his age and worked in the medium that both marked and identified the age – television.

He wrote constantly: scripts, proposals, drafts, letters, chapters of books, the start of journals and for me, postcards. School breakfasts were an expectation of a card from dad. He travelled a lot filming and they’d arrive with pictures of strange cathedrals or exuberant statues and his familiar, timidly excited handwriting that seemed to be fighting its classical pre-war education to become something a little more extempore. The cards were always civilised. He had a passion for museum shops and church porch racks, and his cards were always full of information, facts and observations, wrapped up with pithy, often funny opinions. They were like scenes from a shooting script.

He never wasted time with the ‘Wish you were here, weather’s lovely . . . food’s foreign . . .’ stuff and a small but lasting part of my education came from these postcards. Not least the lesson that anything worth saying can be said both succinctly and elegantly, and that the prime purpose of writing to anyone, be it a letter, an article or a book, is not to show them how clever you are, but to leave them cleverer than they were.

When he finally finished making television programmes he settled down on the sofa with his annotated books and started to write. We’d all encouraged him to embark on a book. He has a charmingly faceto-face style, a turn of phrase that is only a voice away from listening to him; and some memoirs from the pioneering public-service age of broadcasting would have been interesting and a gift for posterity. He’d interviewed Marilyn Monroe, worked with Giacometti and plenty of other interesting people in between. We’d all lived in London during the Sixties.

So it was a surprise when he started writing the story of his childhood. It seemed very previous. When I was a child he told us stories, but they were invariably about his dog, Patch. I had only the haziest idea of his early life or our antecedants beyond my grandparents. I’d never imagined that he really thought it that important. He always seemed to have that self-contained confidence that is the consolation of the only child.

What we didn’t know was that he was, already, incubating the first losses of Alzheimer’s. I write about him in the past tense, though he’s not dead, and I don’t mean to imply that he’s any less alive, or any less my dad, but dementia and the rubbing-out of words, connections and memories are a great and widening moat that separates the him on this side from the man that was on the other.

When I read this book for the first time, he’d already crossed over, and pulled up the drawbridge. It was a huge shock. I’d never heard any of it before. This life that was so vivid, so beautifully remembered and reconstructed. I would never be able to talk to him about it, ask him about this marvellous cast of characters. But as I read it I understood that that was exactly the reason and the rightness for going back. My father was as much a self-made, self-thought-up man as anyone you’ll meet.

The choices we make and the courses we plot are cause and effect of where we started and who we started with. The man my father became and whom I knew wasn’t so much a reaction against the world he was brought up in, but someone who felt that he and his generation had an obligation to change and improve it. I realised there is far less distance between my childhood and my children’s than between mine and my father’s.

There was another pressing reason to write this down. The Alzheimer’s meant that it would all be lost and broken into shards of non-sequitur and nonsense. This book is Daddy committing his memories to the lifeboats, this is what got out, this is what survived and made it safely into print. Women and childhood first.

A.A Gill London 2005

1

DISTANT RELATIONS

I

The first thought that I can recall – something that came from my own mind as opposed to feelings and reactions to outside events – this thought, powerful enough to seem still vivid over sixty years later, came to me on a summer Sunday morning in 1929.

My parents had just built a house in Herne Bay, the small town on the south-east coast of England to which we had moved. It was near the brow of a hill on what was a wheat field when we first saw it. Ours was the first house on a new concrete byroad that was built at the same time.

Every Sunday morning my father would play golf while my mother cooked the lunch. Coming from a Yorkshire farm, she was a very good cook. Often, when the roast beef was nearly ready, we would walk together over the fields to meet my father returning from the golf club in the valley.

One day she told me I could go and meet him by myself. I was nearly six years old and about to start school. I was very proud of the responsibility. She waved me goodbye from the door.

I walked up the road to where it petered out in a wilderness of nettles and thistles and took the familiar path across the fields. Rabbits scuttled away into the hedgerows. I climbed the first stile, between the pallid blooms of wild rose. This was a favourite playground: a wide breast of the hill, comfortable to lie back on and watch the occasional biplane rising and falling as it droned its way across the Channel to distant magical places. A few months before, when it had been bright with poppies, I ran straight into a lark’s nest, a rough twist of grass holding four tiny eggs. Now I walked firmly forward, not even stopping to see how ripe the blackberries were. I was pleased with my independence.

When I crossed the second stile I began to falter; I would soon be entering unfamiliar territory. Then I saw my father coming into sight over the slope. I felt a tremendous wave of pleasure and excitement. I rushed up to him and banged him on the knee, explaining that I had been sent to hurry him up, as lunch was ready. (He was often a little late, if the nineteenth hole proved a long one.)

He took my hand, and told me how the match had gone. Golf was not a game I understood very well, but I liked walking beside him, having a serious conversation. When we had nearly reached our house, my mother came to the doorway.

‘Look,’ I shouted, ‘I’ve brought Daddy home.’

She smiled. Throughout my life she had enveloped me with love and power. Having been away from her on this great adventurous journey, I suddenly saw her as though for the first time. She was beautiful. I felt sure that no one else would ever mean as much to me.

II

Of course, if I trawl my mind back to my earliest memories, many fragmentary images occur. One feeling dominates: pain. A terrible piercing pain that filled my head so that I wanted to wrench it off and throw it away. Instead, I would throw myself about and scream and scream. My head would be wrapped in scarves and laid on a hot-water bottle. This was only a temporary comfort. The pain would return, shooting triumphantly through my head in great throbbing bursts.

Though I remember nothing of it, when I was eighteen months old I was taken to Southampton Hospital and had a mastoid operation on my left ear. I have been told that this was a relatively rare and serious operation in 1925, and especially at my age. It involved chiselling through the bone of the skull. What I thought about it was expressed in my reaction to my father. He had carried me into the hospital and when, weeks later, he came to collect me from my cot, I turned my back on him. Intermittent pain and infections in my ear troubled my childhood for years. This was long before the days of antibiotics. I remember being dosed with a dark sticky medicine of indescribable bitterness.

Illness has been a recurring thread in my life. For years it was assumed by my parents that I would be fit for only the most sedentary job. Fruit farming was the general preference. At that time we lived in Kent, in a landscape jostling with apple trees. I preferred the thought of writing – though it has taken me a long time to get down to it seriously.

That all comes later. My first four years were spent in Winchester in a big half-timbered Edwardian house that my parents shared with my mother’s parents. Memories from those times are like the vivid images from a film trailer. Now I can subtitle them with what my parents told me later. I recall a kindly old man with grizzled whiskers peering down at me as I lay in my pram in the garden and tickling me. I still had a bandaged head, so it must have been soon after my operation. He was Sturt, the first in a long line of benign gardeners who have weeded my paths.

Another favourite was Bailey, my grandmother’s chauffeur. I was fascinated by his olive uniform with its shiny buttons and polished leather gaiters. A ride in the big upright Chrysler was a great treat. It had a silver vase attached to the dividing panel, always with a fresh cut rose in it, and a yellow corded speaking-tube. The glossy fur rug to put over our knees I imagined to be a buffalo skin that had come, like the car, from America. The huge head of a real buffalo that had been shot on the Great Plains by my great-grandfather adorned the wall of the local museum in Batley, Yorkshire. My mother’s family had been mill owners there for generations. We often went back to Yorkshire for Christmas or summer holidays to stay at the family farm – now run by my mother’s elder brother, Tom. He was said to have been a wonderful horseman in his early days. Lean and bow-legged, he had the look of a rider.

I have another reason to remember his legs. On my third Christmas I was given the game of Snakes and Ladders. The board was illustrated by Mabel Lucie Attwell and showed a mustachioed policeman pursuing a plump little dog that had stolen a string of sausages. If you landed on the sausages you slid back down the board; land on a ladder and you would climb up to where the policeman was brandishing his warning truncheon. I was greatly taken by the power this truncheon demonstrated. One morning I went into the kitchen and ‘borrowed’ the rolling pin. I ran along the narrow corridors and steep stairs, from the dairy to the music room, brandishing my new authority at all I met. Eventually I reached the bathroom. My uncle was shaving with his usual care. (He had a different cut-throat razor for every day of the week.) His long, bony legs, bare between shirt-tails and garters, were just on my eyeline.

‘Unc,’ I shouted, ‘I’m a policeman.’

And, in proof, I whacked him on the shin with all my strength. The dent was visible decades later.

Equally memorable was our return to Winchester at the end of that holiday. Much of England seemed to be flooded. Men carrying red flags diverted us down winding lanes where the water lay like glass on every side. It was nightfall before Bailey’s careful driving brought us in a snow blizzard into Hampshire. I dozed on my grandmother’s knee waking to a succession of snow palaces glittering in the headlights. I doubt if I had ever been driven at night before. To my sleepy mind it seemed as though we were entering a magic world.

Eventually I woke with a start to realise the car had stopped, it was pitch dark and Bailey was lifting me out onto his shoulder. I couldn’t tell where we were, but Bailey explained that we were on the last stretch of the road home when the Chrysler stuck in a snowdrift. Sometimes he was up to his waist in the fine powdery stuff. I didn’t mind. I would have liked every homecoming to have been as exciting.

There was still a further surprise. Instead of only my grandparents’ cook waiting to welcome us, the kitchen was crowded with dark-skinned people hugging round them a mixture of colourful rags and our blankets. Their strange chatter was hushed as Bailey carried me through to my nursery. He knew them, of course. They were the gypsies who lived in two caravans over the hill. Lacking any heat except peat fires, they had been given shelter from the blizzard by our kindly cook.

This bastion of caring, cheerful servants peoples my memories of Winchester. They came to us, as did the big house itself, through the generosity of my uncle in Detroit. My mother’s families, the Taylors and the Thomases, had started emigrating to the States in the 1830s. Each generation sent over a fresh wave. My mother’s favourite brother, Clifford, went to join his uncle when he was sixteen. He returned to lose a leg fighting at the Somme. This had not impeded his financial success as a stockbroker. His business acumen was no doubt aided by his personal friendships with Detroit car builders such as Edsel Ford. He never gave up his British citizenship or forgot to share his good fortune with his parents in the old country.

By contrast, my father’s family was solidly working class. Both my grandfather and my great-grandfather spent their lives in the noisy dusty caverns connected with the clothing industry.

The mill owners, like my grandfather’s family, the Taylors, built big houses for themselves on the hilltops. The factories were down by the fast-running stream, and on the steep slopes between were the long rows of workers’ cottages. We used to visit my grandfather George Gill when we were staying at the Taylor farm. My grandfather was a stocky man with a heavy beer belly. He smoked a pipe and when he bent to kiss me his moustache smelt of tea and tobacco. I liked him, though I thought his house much too small. There were only two rooms, one on each floor. The front door opened straight in from the street. There was room for a couple of shabby armchairs. Then the room changed into the kitchen with a long coal-fired range that included an oven and heated the water and the cottage itself. A sink, a table, two wooden chairs and a larder completed the downstairs furnishings. The narrow stairs ran up the side wall. The upper room had a double bed and a smaller bed in which my father and his elder brother slept through their childhood. A blanket pinned to the ceiling divided the generations. What would they have done if they had had a son and a daughter?

Out the back there was a water tap (this was a recent luxury; beforehand they had had to use a pump at the end of the terrace); a clothes line, a heap of coal (part of my grandfather’s wages was a sack of coal a week) and a shed housing an outside lavatory shared with the neighbours.

Reviewing it, I’m struck by how efficiently it covered the bare necessities. No radio, no TV, no CD. No supermarket range of goods. My grandfather had one week’s holiday a year. He always spent it with us in Kent. While with us, he and my father would take a day trip to Calais or Boulogne. He would send French postcards to all his cronies in Dewsbury. It was the high point of the year.

I cannot remember my grandfather losing his temper, or seeming discontented with his lot. I never met his wife, my grandmother. She was said to be highly strung and to adore her clever younger son Arnold, my father. During the First World War she received an official telegram informing her of his death in action. It was untrue – he was not even wounded – but she suffered a stroke from which she never recovered.

My grandfather accepted this loss with the resignation that he showed in so many different ways. He had a consolation. He was a brilliant wood-carver. He could make cabinets and bed tables and chests of drawers of a perfection that made it a pleasure to touch them. I still have a bed table he made for me in my years of illness and a smoothly articulated tool chest. And, as often with a skilful craftsman, he acquired a companion to compensate for the long lingering death of his wife. Because of this unmarried woman friend I was never allowed to spend as much time with him as I would have liked.

III

A mouse robbed me of a sister. Running across the kitchen floor, it so startled my pregnant mother that she jumped on a chair and had a miscarriage that evening. At the time I was three and a half and knew nothing of such things. I missed my mother at breakfast (she went on a recuperative cruise to the Canaries with my Aunt Mabel). In compensation I saw more of my grandparents.

I was in awe of my grandfather, William Taylor. He was very kind, but he often seemed far away. His white imperial beard made him look like the King (I sometimes mixed them up). There was no mistaking my grandmother.

Emily Ann Thomas was handsome rather than beautiful, dark and vivid. In her youth she looked Spanish, her eyes deep pools in the powerful angles of her face. She was always very trim and erect. In her thirties, when she had spent some eight years married to her cousin William Taylor, a charming but improvident farmer, she looked quite different. A wild defiant gaze must have reflected the pains and disappointments of life with an alcoholic. It was her inheritance that kept the farm going.

The money came from the piano factory that my great-grandfather had set up in Kilburn in the 1860s. A skilled craftsman in furniture, he made the casing while his German partner provided the musical parts. When my grandmother was in her late teens she was entrusted with collecting the weekly wages for the factory hands. She carried this considerable sum of money in a leather briefcase that was chained to her wrist. One Friday she was walking back from the bank along the busy Kilburn High Road. A man darted out of an alleyway and grabbed the bag. He nearly dislocated her arm, but was unable to break the chain. She resisted as best she could, but was dragged further and further down the deserted alley. None of the hurrying passers-by took the least notice. She was thrown from side to side and retaliated by beating at the man’s head with her free hand. He was quite a small fellow, she remembered, when she told me half a century later.

‘Didn’t you call out?’ I asked.

‘No, that was the strange part. We neither of us said a word.’

When she felt her strength was nearly gone, a policeman appeared at the end of the alley. Her assailant ran, leaving her with a bruised and torn arm.

‘Did you carry the money the next week?’

‘Yes, but one of the bigger factory workers came with me.’

That was my grandmother. She would not let a small misadventure put her off carrying out her duty. Brought up in a mid-Victorian house in London, where music was played and German spoken as a second language, where there were regular visits every few years from relatives across the Atlantic, she acquired a sophistication and poise she never lost. Even though I knew her only in the last few years of her life, I was aware of the close relationship she had with her only daughter, my mother. My grandmother’s strength of character was always a support for her gentle, inherently shy and sensitive child. My mother also visited America, first when she was twelve and then she spent a whole year there when she was eighteen, but she preferred the moorlands of the Brontë country to the hustle of the New World. That might have been all right for my mother, but for my grandmother a small farm in Yorkshire was not a good exchange for a mansion in Kilburn.

Why did my grandmother throw herself away on her fecklessly charming country cousin? He was the youngest son of the Taylor whose factory processing shoddy or woollen waste was one of the many polluting the atmosphere of Dewsbury. There was nothing for William to inherit but the farm, which his father had acquired only as a hobby.

My grandmother with her sharp business sense must have realised it was never going to make an adequate return. Why did she not insist that William follow the example of her own brothers, who were doing extremely well in the booming Midwest? William had no ambition; he liked the country life and the chummy drinking bouts that followed the local cricket matches. There was no cricket in America. He himself had been an elegant batsman. Perhaps it was his physicality that kept the unlikely couple together.

My grandmother had had many other admirers in her youth. One was still with us in Winchester. Henry Talbot had fallen for her when she first appeared in Yorkshire society some forty years before. His devotion never flagged. He never married and lived with a spinster sister on a small inheritance. He and William used to go up to London to watch the test matches, staying in Henry Talbot’s club. When his sister, his only close relative, died, it seemed the natural thing for him to move into a spare room in the farm and later into Pitt Corner. In Winchester, he had his own bedsitting room and bathroom. I took his presence entirely for granted. He would take me for walks.

We would go to a big pond in a hollow and throw the ducks scraps of bread. I was probably not a very accurate thrower. The ducks would come clamouring out of the water and once I was bitten by an importunate drake. I can still remember how curious it felt; like being slapped with wet rubber. Climbing out of the hollow, I would take Mr Talbot – Tor as I called him – by the hand. In it would be a boiled sweet wrapped up in paper. Nothing would be said, but when I had finished it another would miraculously appear.

These satisfactory excursions cannot have lasted long. Tor vanished out of my life with no more explanation than went with the appearance of the sweets. Years later I was told that he had been arrested strolling down Winchester High Street in his shoes and spats. He was always a meticulous dresser, but on this occasion he was wearing nothing else. Shortly after he had a brain haemorrhage and died.

His old drinking companion soon followed him. I knew my grandfather was ill. Even on the warmest days he would sit wrapped in a rug in a sheltered corner of the garden. I would take advantage of his somnolence to creep up close and study every aspect of his appearance. I was particularly fascinated by his hands. Long and slender, his fingers lying on the rug seemed almost transparent, as fragile as our best-quality china, which I was always being warned not to drop when it was brought out for Sunday tea.

2

A FRIENDFOR LIFE

I

The Scottish soldier sat at the entrance to his tent. He was a blaze of health and colour: scarlet jacket, scarlet and green kilt, fair moustache, pink cheeks, pink knees, a dirk sticking in his fat stockings. His Indian servant stood at his elbow, impassive and attentive in immaculate white. Beneath their feet the grass was bright green. Behind them, I imagined, loomed the gloomy defiles of the Khyber Pass and beyond, glittering peak on peak, the Himalayas. I had to imagine that, because what I actually saw were the upraised noses of the Bisto Kids, sniffing appreciatively at the cardboard steam. There were other cut-outs in the window of the village shop: a prancing golliwog advertising marmalade, the gleaming teeth of the Eno’s girl; but it was this big central group for liquid coffee that held my attention when I first passed by in my baby chair.

I still got whoever was pushing me to stop. It was a sort of indulgence, because now I was eight years old and could read in Wizard the adventures of King of the Khyber Pass and his squat servant, who cracked the heads of recalcitrant tribesmen with his battered cricket bat, Clicky-ba, and in The Times of the bombing of villages in the region by the RAF. It seemed there was always trouble on the Frontier. My father thought they should send T.E. Lawrence to deal with it. Would he grow a beard and carry two long curved knives like King? Was he really needed? Surely nothing could be more imposing than the Scottish soldier. I would have looked longer, but my dog, Patch, grew impatient and jerked at his lead. It was tied to a spring of the spinal chair and the bouncing told me it was time to move. Patch was lifted onto my lap and I stroked him quiet. He was small and fluffy and a wire-haired fox terrier. He had replaced Teddy, my bear, as my closest companion.

Illness had grown imperceptibly from a temperature, which would not return to normal after a cold. I was moved into my parents’ bedroom. The flower patterns on the wallpaper took on strange shapes, fluctuating and twisting. I watched them from the end of a long tunnel, infinitely receding. Just to be lifted up while the sheets were straightened was exhausting. One day the doctor stood with my parents upside down on the ceiling at the foot of the bed and told me I must hang on. The voice that answered did not seem to be my own. For some time I existed on lemon ice cubes and vitamins fed through a tube rectally. It was an odd, soothing sensation and used to send me to sleep. Eventually, wrapped in blankets, I was taken to London to see a famous children’s doctor. He looked like the photograph of J.M. Barrie in my Peter Pan book. His name was Sir Frederick Still. I sat on his knee and he probed me with gentle, bony fingers. It was decided I had a disease from milk, bovine tuberculosis, with complications. The treatment was rest. I rested – altogether for five years. The first three I was mostly flat on my back.

I did not regard this as an imposition, except during the ferocious attacks of vomiting which were among the complications. Indeed, especially after the first few months when I could be pushed out in the long wickerwork spinal chair, I thought of myself as singularly privileged. I knew I got more attention than the ordinary boy. So many interesting people would come up and talk to me. An only child, I did not miss the company of children. How many enjoyed the friendship of a talking raven? He would join us near the village shop, and pace alongside the carriage like a black hunchback, causing Patch to retreat between the wheels, growling quietly. Occasionally the raven would hop onto the wickerwork side of the carriage and utter a cry so wild and desolate that it prickled my hair. His actual conversation was more mundane. He could say ‘How d’ee do’ and ‘What’s your name?’ over and over again in a tiny mechanical voice. Often he refused to say anything. He was the pet of an old bachelor with a straggling moustache and watery eyes. He persuaded me to read Bevis: The Story of a Boy, by Richard Jefferies, and Kenneth Grahame’s The Golden Age. I think now this must have been a form of inverted pity, as both were stories of active youth. I found them very boring.

Much more to my taste were the anecdotes of a couple who lived on the edge of the village. They often came out and invited me into their big old house. The carriage crunched over the drive between dark pine trees and neglected flower beds, bumped up the stone steps, eased through the door and into a world of dusty marvels. Lion and leopard skins, the head of a rhinoceros, the heads of deer with twisted horns, barbaric masks, shields, spears and lumpish clubs crowded the walls. Huge tusks stood in racks in the corners, there was carved ivory from Zanzibar, knobkerries from Zululand, drums covered in monkey skin and tufted with the beards of gnu. The man had been a district officer in Africa in Edwardian times. Plump now and a little moth-eaten like his trophies, he told terrible things in a kindly way. He would let me finger the gnarled surface of the thirty-foot-long rhinoceros-hide whip. One flick could lift a strip of skin ‘as thick as your finger’ off the back of a recalcitrant servant.

He pointed out the grains of greyish powder in the grooving of a spear.

‘Deadly poison.’

‘Would it still work?’

‘Oh, I expect so.’

I fingered the dry, almost weightless, skin of a mamba, the coarse hide of a zebra, the bristles of a wart hog, and touched the sharp barbs of a fishing spear. I learnt how the lightest tap could set a drum vibrating, and how it was speed of impact rather than force that could send the sound ringing round the ceiling.

They were a childless couple and they never seemed to mind lifting things off the walls, or bringing them down from the attic, so that I could touch that hot dusty continent that had dried them and weathered them and finally exiled them to this untidy house in Kent. They had been friends of Cherry Kearton, the writer and lecturer on wildlife. At his suggestion the wife had taken up photography. She had mounted her pictures in many albums and would point out the exciting ones.

‘That elephant is about to charge the camera; see how he’s spread his ears and put his tail up.’

‘Did you take the picture?’

‘Yes.’

‘What happened?’

‘Frank shot him.’ Small and practical, her hands flicked through the sepia pages.

‘Those are Watusi; they’re over six feet tall and they never wear a stitch of clothing.’

‘That crocodile has caught a pigmy deer.’

‘Beastly things, crocodiles,’ said her husband. ‘Used to give me the willies.’

‘What about snakes?’

‘Oh snakes are all right. A snake won’t hurt you unless you hurt him.’

Since then I have met other couples that sufficiently reminded me of them to make me think they are a type that endures in harsh and alien environments: modest, quiet, bound together by mutual loyalties, too lacking in self-regard to notice the idiosyncrasy of their enthusiasms; commonplace in every way, really, except in what they expected of themselves and of each other. At the time I hardly thought of them at all. I was occupied with the world they showed me.

In bed at night I would remember some photograph of an expedition weaving its way through tall grasses and baobab trees, Frank in front, pith helmet on his head, rifle across his shoulder, and behind the line of bearers, half-naked, anonymous, black skins gleaming. Travelling with them along that twisting trail, the heat sweating my back, stumbling past roots and vines, caressed by hot winds, wrapped in dark rich smells, inhaling the aroma of exotic flowers and nameless beasts, entranced by the flutter of vivid wings, I felt the fear of unknown danger. Would I be the one who caught the flicker of velvet skin stalking through the yellow grass? Over thirty years later, as the jet circled down to the landing field and I saw for the first time such paths crisscrossing the bush and the bright splashes of colour of the women’s djellabas as they went in groups to the waterholes, it was then that I thought of Frank and his wife.

Our house stood on a hill. On top was the village; below, the small seaside resort of Herne Bay. Sometimes my parents would push me to a tea-shop there. It was run by a friend of my father’s. He was a thin sallow man who had lived for years in China as the agent of a tea company. His café was full of bric-a-brac from his stay – red pagodas, and huge blue and white jars and tiny model gardens, perfect in every detail. The man himself interested me most.

‘Show me, go on, show me.’

He would glance at my parents and then with a deprecatory laugh, bend towards me, lifting the grey hair from his ear. But there was no ear; only a dull red hole.

‘Now show it to me.’ He went to a lacquer-work desk beyond the potted palms and brought back a small cardboard box. He offered it to me.

‘You sure you want to see? You open it then.’

‘Ugh, no I couldn’t.’

‘It won’t bite you know.’ Lying on cotton wool, it looked like a piece of dark brown rubber. It felt rather like rubber, too, when I could bring myself to touch it; something as difficult to do as stroking the back of a pet toad – fascinating and disgusting at the same time. He had lost it during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900. Bandits had taken advantage of the unquiet times to kidnap him. They had held him to ransom for months in a cave in the mountains. Growing impatient, they had sent down an ear as proof of his captivity.

‘Didn’t it hurt?’

‘I suppose it did. I was really more worried they were going to cut off my head.’

Eventually the ransom was paid, and a friend returned the severed ear. He had kept it with him ever since. Oddly enough, I found this the most disturbing part of the story: to live with your ear, but separate from it, all those years.

This old China hand upset our family in a more concrete way. Occasionally he would sell a piece from his collection and my father bought a Buddha. It was about two feet high in gleaming highly coloured ceramic. My father put it on a table in the hall. Obscenely fat with shiny bald head and wide smile, it immediately commanded the space around. It even dominated the grandfather clock, the oldest member of the household, which had been with my mother’s family for nearly two hundred years. It was not only that it seemed incongruous among those familiar sober furnishings. It introduced an alien presence into the house. You could feel it as far away as upstairs, silently gathering power. A mysterious realignment of forces was in progress. The hall was no longer our hall, but its shrine. The next morning my mother announced that it must go. She had experienced horrible nightmares and she knew it was a nasty wicked thing. We did not disagree. My father wrapped it up carefully and took it back. The clock resumed its old peaceful dominance of the hall, as it was to continue in other halls, ticking away, the metronome of my parents’ lives, and later of my own.

II

About the time he bought the Buddha, my father took up Pelmanism, joined the Freemasons and attempted, unsuccessfully, to record in short stories his experiences in the First World War. My mother had just prohibited him from playing golf, a game of which he was very fond. He was a natural games player; had been in the Tank Corps rugby team at the end of the war, and played tennis well. My mother had also enjoyed tennis in her youth, but she never played in my lifetime and disliked any activities that kept them apart.

That same summer there was an occasion when my mother ran round the room after my father, dodging tables and chairs until she caught him and tickled him so unmercifully that they both fell to the ground, rolling about and laughing. Such physical exuberance was rare. For over forty years my parents were obsessively devoted to each other. They almost never spent a night apart. Yet sexual matters were unmentionable and also, my mother inferred, disgusting and unclean. She was very fastidious, and would actually shiver at any account of drunkenness or coarse behaviour. Perversely she had a number of such stories to tell, because her family had contained some notable drinkers. This was hard on my father, who liked a convivial pint. She often subtly discomfited him.

My father won a scholarship to the local grammar school, became head boy and wanted to be a doctor, but his father, the factory worker, thought it safer to put him in a bank. Even as a very small child I knew my mother was superior – though it is hard to define precisely how I knew. My father was the more intelligent of the two and outwardly took all the important decisions. He was very patient. I cannot remember him making a critical or unkind remark about anybody. As a young bank clerk he had taught in a non-Conformist Sunday School and though he never went to church after the First World War, I think of him as a morally good man.

My mother had taken on his job as a bank cashier as war service. When my father returned after the war and they met for the first time, she was suffering from a great loss. In 1914 she had become engaged to the dashing, well-to-do son of a mill owner. I know he was handsome because, years later, she showed me his photograph, taken that last summer of peace on the beach at Scarborough. He never came back, of course; though by an irony of fate he died after the war was over, on the North-West Frontier of India. In her sorrow my mother came to rely on the serious dependable young tank officer, two years her junior. It was a long time before they married, and I doubt if my father ever took the place in her heart of her first love. But she trusted him and he always did what she wanted.

Their relationship withstood some harsh and bitter times. They were unlucky in that, meeting under the receding shadow of a terrible war, another even more devastating conflict dismembered their middle years, and in between they had the anxieties of bringing up a chronically sick child. That first winter of my TB fever, my grandmother was also ill with terminal cancer. At one period there were two full-time nurses in the house. In the midst of my ochre and magenta dreams I would hear my grandmother’s groans of protest at being turned over in bed in the next room. My hold on reality was so unstable that I sometimes thought it was another part of me that had split away and was moaning to return. It must have seemed to my parents an awful (and expensive) burden to bear. Yet they were never other than kind, loving and considerate. My father had come to regard my grandmother almost as highly as my mother did. Crisis steeled their reliance on each other.

They grew together so that, over the years, even their writing came to look alike. Yet there was something stultifying in their affection. Outwardly so contented and inwardly so close, they fed on each other. They did not dare to look far aside. She was a woman of deep but narrow feelings, centred on the home and her immediate family. I remember thinking how dull their lives were when I was very small. Because of what I intuited from her I tended to look down on my father (though I loved him, too). I think I must subconsciously have wanted him to make more of a stand against her, but he never did. As I grew older I came to understand him better and admire him more. Then I threw the blame on my mother; not difficult to do as she looked at the outer world with a mixture of fear and gentle snobbery. Now I feel there was a tragic inevitability in their relationship. Once, later, when we were living in Canterbury and had a car, my mother slipped on the wet gravel drive as she was getting in and fell. My father, running round the bonnet to help her, slipped and fell as well. Neither was hurt, and watching, safely tucked up in rugs on the back seat, I thought, with the cruelty of childhood, that it was a funny sight. It was also symbolic; they were paralysed by their mutual concern.

III

So my father gave up golf, and eventually found in gardening the ideal activity he could share with my mother. He was an instinctively hard worker. Though he had never wanted to be in a bank, he stuck at it and became, at 33, the youngest manager in the Midland at that time. Banking was something my parents had in common. Her wartime experience as a cashier had given my mother a lively appreciation of money, and every evening they would discuss the problems and people he had encountered that day.

Herne Bay was under two hours by train from London’s Cannon Street and in the 1930s was a growing dormitory area. Whole estates of flimsy bungalows, of mock-Tudor semi-detacheds, sprawled along the cliffs and grew over the fields that had once crowded so close to the town. ‘Jerry building’ was a phrase with which I was familiar long before I knew what it meant. There was something gimcrack and depressing about those characterless suburbs, where the gardens were still raw earth and weeds and the concrete ribbon roads had begun to slip and shift almost before they were dry, so that the wheels of my spinal chair would bounce over the asphalt strips that joined the sections.

Each evening on a weekday the owners of these new mansions would return from their labours in the City. Sometimes in summer I would be pushed out to watch them. At 7.15 the train would come in and dozens of sallow-faced men would pour out of the station. Dark-suited, bowlerhatted, each clutching an umbrella and a rolled-up copy of the Evening Standard, they seemed like a macabre army as they fanned out down the side streets, hurrying without a sideways glance towards ‘Mon Repos’, ‘Sea View’, ‘Uplands’ and their supper. Some residents were less prosaic. At least three of our neighbours went to prison for embezzlement – a term I understood as little as ‘appeasement’ and ‘sanctions’, which were soon to be in the wind.

The London evening paper was dramatically responsible for increasing my knowledge of the world. You could buy the afternoon edition at Herne Bay station and in May 1930 my father bought it every day. A unique journey was under way. Amy Johnson was flying to Australia. Alone. Without radio. In a second-hand little plane with an open cockpit that had already flown thirty-five thousand miles. Amy herself had been flying for only eighteen months. In photographs she looked more sturdy than her Gypsy Moth.

No woman had ever made such a journey. Each day the paper published a map showing where she had got to. I began to understand that the world was much bigger than I could imagine, when the distance between my fingers was over a thousand miles. Amy Johnson, with her pleasant North Country voice, seemed, as all those lone flyers of the 1930s were to seem, an augury of the future – a symptom that this great big world which I was being introduced to day by day in the paper was going to be encompassed. If an ordinary young woman could do it, others would. Perhaps I might one day. (When the wings of her plane were pierced by bamboo spikes in a forced landing in Java, she mended the holes with sticking plaster. What an adventure!)

Occasionally, even in Herne Bay, I would catch a glimpse of someone whom I heard described as a real adventuress: a beautiful young woman with startling blonde hair and a big fur coat coming out of a shop would give me a smile or bend to pat Patch with jewelled hands. My mother would look flustered, her pace would quicken and her lips compress.

‘Why don’t you like her?’

I never got a satisfactory answer, but later I knew. She was a local girl who had become a fan dancer in a London nightclub. There she caught the eye of a maharajah who had installed her with her parents in one of the new bungalows on the sea front. He appeared only occasionally, racing through the High Street in a white Lagonda, but he constantly embroidered the dreams and anecdotes of the town. Envy and spite were not my mother’s vices, but distaste for sex was another matter. I was never allowed a long conversation with the Scarlet Lady, but I remember her kindly glance and vivid appearance, so out of keeping in those dowdy streets. What was the mystery about her? Something ominous that grown-ups knew and I did not; yet even lying in my spinal chair I was beginning to feel its stirrings.

On Sundays my parents would often push me to the end of the pier. At three-quarters of a mile it was the second longest in Britain. I liked the alteration of sound once the land was left behind: the echoing clank of my parents’ feet on the slats; at first the cheerful cries of children playing on the beach coming up from below; the hum of land traffic fading under the approaching wash of the sea, endlessly varied as it broke on the metal struts and pillars; the reverberating passage of one of the two trams that ran up and down the pier, grinding slowly along to the insistent clang of a bell; finally to feel enveloped by the murmur of the ocean, the screech of gulls, the occasional hiss of an angler’s line. Peeping over the edge of my chair I could look directly down at the water through the gaps in the slats. Swirling, green, foaming and opaque, always racing forward and retreating, it seemed the opposite of the motionless world I inhabited. Away it stretched to a limitless horizon, fading into the blue of the sky. Beyond there was France, but those smudges heading west down the Channel would be going to more distant places, Brazil and Africa and Mandalay, unimaginable coasts and tropic shores. A bottle thrown with a message in it might float all the way to Treasure Island. It was as if the world were a vast drum of which the skin was the sea; sitting on the edge, were I to tap it the reverberations would go on forever. Crouching on my rug, Patch would snuff the salt wind and sneeze.

Walking back along the front, past the Edwardian bandstand and the 1920s Pavilion where the Fol-de-Rols played in the summer, my parents would stop at the Italian ice-cream shop for a coffee. It came from a huge bubbling and hissing machine, very newfangled then. The proprietor was as cheerful as his brightly painted furniture. He seemed an innocent contrast to the ambiguous ruler of his country, about whom, I gathered, opinion was divided. People said he had drained the Pontine Marshes, a feat reminiscent of Thor’s in drinking up the sea. My friend the milkman said he should stick to his spaghetti – he looked as if he’d eaten plenty – and stop going on about them poor natives. These views didn’t affect custom at the ice-cream shop, even though the proprietor had pinned up a newspaper photograph of Mussolini skiing bare-chested in the snow. Tactfully he put it below the large framed photograph of our own old King that occupied the centre of the wall.

I was allowed an orange water ice and my father would go to the paper shop next door for the Sunday Express, the Sunday Times and a comic for me. My favourite was Boys’ Magazine. I preferred it to Magnet and Gem – the schoolboy antics of Billy Bunter, Bob Cherry and Harry Wharton were as remote from my experience as life on the North-West Frontier and much less exciting. Boys’ Magazine was running a serial about a return to a lost world of giant animals, capitalising on the current success of King Kong.

In the stories of my favourite writer, John Hunter, there was a recurring note of horror and pain, beyond the general bombast of such comics as Wizard. The arch-criminals would often employ evil demons, fit for a medieval fresco, that would spirit the drugged hero from his bed and flit with him held in giant claws, high above sleeping London, to a remote mountain eyrie, there to face interrogation, torture and death. Death never came to the hero, of course, but tortures were many, ingenious, described in detail and only escaped with agony. A typical example would have the naked hero, tied hand and foot, and weighted with corks, placed on his back in an empty bath. (Though this was being done by masked, chanting monks in Tibet, I imagined the bath to be exactly like mine at home.) A red hot grill was placed over the bath, which was slowly filled with icy water, straight from the Himalayas, lifting our hero inexorably towards the glowing bars. Would he first freeze or burn? Read next week’s thrilling instalment. It was those painful episodes that made me read Boys’ Magazine so avidly.

The prevalence of such themes in boys’ literature suggest they fulfil some need. I doubt if girls have a similar taste. And in my case there were additional reasons. Decades later, in a general surgical ward, I noticed the most popular books were the novels of Ian Fleming. Their many accounts of torture and unpleasant death would seem inappropriate relaxation for advanced cancer patients, yet the opposite seemed to be the case. Perhaps it was a relief to read of miseries worse than one’s own, and to identify with a hero who, though apparently helpless, was usually able to master his dangers by his physical and mental adroitness. Perhaps; though what I remember of the long afternoons when I would lie resting in my spinal chair in the garden, was the pleasurable dwelling on the torments themselves and not how the hero might avoid them in the next episode. Maybe it was a way of communing with my own condition and making my weak, trapped, unnatural life more acceptable. Consciously I did not, of course, regard it in this light. I knew myself to be extremely fortunate to have such an unusual existence. Perhaps my unconscious was having its own back, seeping subversive thoughts into me through the icy water trickling along the back of the hero in the bath. I had given considerable thought, too, as to which part of his anatomy would first come into contact with the red hot metal. I had no doubt which it was and that added to the uncomfortable guilty pleasure.

IV

My parents employed a genteel maiden lady called Ruby Arnsby to take me for walks during the week. She was in her forties and lived with her invalid mother. For some reason her heavy application of powder, the cloying wafts of sweet scent which preceded her into the room, and the cooing way in which she would correct my homework, infuriated me. One day I showed her a series of drawings I had done. At this time I filled sketch pads with the adventures of heroes such as Tarzan drawn in comic-strip style. I told her this batch were of Odysseus on his voyages. Actually they showed a naked bearded man having awful things done to his penis. In one it had been hooked onto a pulley and line and he was being hauled towards the ceiling, though weighted down by a heavy stone. In another, he was strapped to the ground while a whole tug-of-war team hauled on a rope attached to the unfortunate part. In every case the effect was the same: enormous extension. I must have meant to shock her and I succeeded. My parents never referred to the incident, but Miss Arnsby was replaced by a young man.

Jack Packham was the son of neighbours. A stills photographer with a film company in London, he had taken pictures of the young Gracie Fields, but lost his job in one of the endemic slumps in British films. He was twenty-nine, unmarried, a shy, gentle, melancholy person, and an indefatigable walker. Every morning he would call for me at nine o’clock and push me eight or nine miles before lunchtime. Sometimes we would go up through the village of Beltinge and along country lanes to the ruins of Reculver. Originally a marshy five miles inland, they now stood on a mound above the encroaching sea. Two gaunt towers with only a few coastguard cottages nearby, they were desolate and forbidding even in summer. The actual towers were of medieval flint, but some of the broken walls were Roman. Jack showed me how to identify the narrow bricks. The gloomy atmosphere had no effect on Patch, who went bounding across the stones and over the fields after the rabbits.