Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

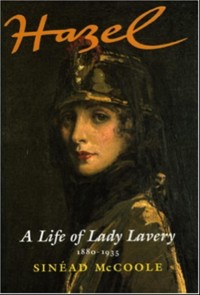

Lady Lavery has been remembered for the numerous portraits by her husband, the painter Sir John Lavery, celebrated in 'The Municipal Gallery Re-visited' by W.B. Yeats. This first biography of Hazel, first published in 1996 and now reissued, tells the story of how a girl from boomtown Chicago became one of the most stylish society hostesses in London, turning her husband's studio into a hub of Anglo-Irish diplomacy, from the 1921 Treaty negotiations through the tumultuous early years of the Irish Free State. Using hitherto-unpublished letters and scrapbooks, Sinéad McCoole gives a vivid account of Hazel's artistic and political preoccupations, and of her extraordinary effect upon the male politicians of Ireland and Britain, for whom she and her salon represented common ground. Romance and politics converged in her relationships with two hard men of nationalist Ireland who each met violent deaths, Michael Collins and Kevin O'Higgins, whose passionate letters to Hazel reveal the inner man beneath the political carapace. Hazel also forged durable alliances with the pillars of British government – Winston Churchill, Ramsay MacDonald and Lord Londonderry among others – while relishing friendships with leading writers of the day such as G. B. Shaw, J.M. Barrie, Lennox Robinson and Evelyn Waugh. This lavishly illustrated, richly documented life of Lady Lavery relates how one beautiful American woman reinvented herself as 'a simple Irish girl' and came to personify Eire on Ireland's banknotes, 'living and dying ... as though some ballad-singer had sung it all'.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 505

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

HAZEL

A Life of Lady Lavery 1880–1935

Sinéad McCoole

To my mother Barbara and my late father Michael

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Preface

Acknowledgments

I ‘THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE MIDWEST’

II ‘MOST GREAT AND WISE AND SOLEMN JOHN’

III ‘THE SIREN CALLS’

IV ‘ALL WIFE’

V ‘A SOCIETY STAR’

VI ‘A SIMPLE IRISH GIRL’

VII ‘GUIDING THE SPLENDID STUDS’

VIII ‘THAT MOST LOVELY AND CRUEL COUNTRY’

IX ‘HEARTSICK OF ALL THINGS IRISH’

X ‘IT IS FINISHED’

EPILOGUE

Notes and Sources

Catalogue: ‘Hazel, Lady Lavery: Society and Politics’ at the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery

Index

Plates

About the Author

Copyright

Preface

Had it not been for Hazel’s portrait as the colleen of Irish banknotes, her features and even her name would be now forgotten in a land which has never accounted gratitude amongst its theological virtues. – Shane Leslie1

This rueful assessment of history’s short and selective memory provides the most obvious rationale for a biography of Hazel, Lady Lavery. Her role as a social diplomat during the Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations and their aftermath has frequently been dismissed. Social history by its nature is difficult to document, which may account in part for Hazel’s absence from the dominant historical narrative of the period. As the truth about the lives of the founding fathers of the Irish state comes into fuller perspective, those marginalized at their expense – such as Hazel Lavery – regain their stature.

There has been persistent interest in chronicling Hazel’s life, starting with Hazel herself, who wished to publish her correspondence but was prevented by illness. Those letters, many of them published here for the first time, reveal both the breadth of Hazel’s social connections with the leading writers, artists and statesmen of the day, and the depth of her political commitments.

Her husband, the painter Sir John Lavery, was to write in his autobiography TheLifeofaPainter (1940):

Hazel left behind a trunk full of letters and mementoes of those days. It is not for me to disturb them … But neither in paint nor in words do I feel I could ever do justice to Hazel. Her rare beauty of face and character must have been known personally to be believed, and so upon the things nearest to me I will write least.2

In 1940 Sir John wrote to the novelist Louie Rickard, ‘Of all Hazel’s friends it was to you in her last sad months that her love and thoughts went – I know that if a record of her life was to be written it would have been you she would have chosen to write it.’3 The Irish playwright Lennox Robinson approached John after Hazel’s death seeking to compile a book he intended to call LetterstoHazel, but John denied him permission.4 Osbert Sitwell wished to pen Hazel’s life but his ambition never came to fruition.5 Shane Leslie also toyed with the idea. He wrote, ‘Many, who were enchanted by her on earth, hoped they would be allowed to write her biography.’6 Lady Lavery’s only child, Alice, believed that she could set down her mother’s life story, but found the cares of family life encroached upon her desire to write.7 She also questioned her ability: ‘What could I write about that has not already been told, and much better, by someone else, but for my own amusement, or my children’s, I might make an attempt one day.’8 Shane Leslie suggested to Alice that their stories of Hazel should be put ‘in a sealed envelope’ for the benefit of ‘the historian of 2000’,9 but this never happened. John himself produced a particularly durable monument to Hazel’s life in the form of over forty portraits, but in his own rambling, somewhat inaccurate autobiography, the frequent references to Hazel are tantalizingly brief.

In the 1950s Lady Audrey Morris, who had known Hazel, began a biography. For eleven years she assembled a huge volume of documentation and recorded contemporary reminiscences, but many of those interviewed refused to have their statements published. The suggestion of Hazel’s romantic involvement with major political figures, particularly the Irish nationalists Michael Collins and Kevin O’Higgins, would have been especially controversial. Leslie wrote to Lady Audrey:

… it is an excruciatingly difficult book to write especially as so much ms. material has disappeared … much is quite impossible to tell. Remember Miss Collins is alive and the widow of Kevin O’Higgins. If Hazel’s correspondence with those Irishmen Collins and Kevin were published or even their relations were truly portrayed there would be woe in Dublin and much protestation.10

Restrictions were imposed by Alice and the manuscript was never published. This biography has made extensive use of Lady Audrey’s invaluable research, in which the voices of Hazel’s contemporaries are preserved. In quoting from letters, I have left intact aberrant spelling, punctuation and syntax, without comment, except where these impede comprehension.

This work originated in research undertaken for a Master’s thesis entitled ‘Lady Lavery, Her Salon, and its Role in the Emergence of the Irish Free State’ for the Department of Modern Irish History at University College Dublin. When I began my research in 1990, only fragmentary archival material could be found. I located Hazel’s daughter, Alice Gywnn, then living in Co. Meath, but it was only possible to interview her three times before her death in April 1991. When scholars had approached Mrs Gwynn earlier, she claimed she had burnt all her mother’s papers. However, after her death a large cache of letters and scrapbooks came to light in the attic of Rosenalis, to which I was kindly granted access. Hazel had created her own remarkable archive of correspondence, newspaper clippings, photographs and other documents; this work is largely based on these sources. All uncredited drawings, letters and photographs used here come from the scrapbooks. Hazel deliberately shaped the record of her life. Conspicuous by their absence are the letters from family and friends not in the public sphere. The Lady Lavery Collection will no doubt provide the foundation for a fuller study in future.

Shane Leslie’s words now seem prophetic:

In due time this biography or rather illustrated souvenir will reach the record. … No one, English or Irish, who shared in those times, would now care to be without some kind of biography of Hazel. In the matter of her friendships and admirers, future historians will insist on being frank, as history in due time has always allowed them.11

Notes

1 Shane Leslie, ‘A Memoir of Hazel Lavery’ (undated) – Leslie papers in Georgetown University Library, Washington D.C. (herein Leslie MS).

2 John Lavery, TheLifeofaPainter (London 1940) (herein Lavery, Life), p. 198.

3 John Lavery to Louie Rickard (6 March 1940) – Lady Lavery Collection (herein LLC).

4 Lennox Robinson, CurtainUp (London 1942), p. 206.

5 Alice McEnery to Father Leonard (10 January 1936) – Father Leonard papers in All Hallows College, Dublin.

6 Leslie MS.

7 Alice McEnery to Father Leonard (12 June 1936) – Father Leonard papers in All Hallows College, Dublin.

8Ibid. (10 January 1936).

9 Shane Leslie to Alice McEnery (12 January 1949) – Alice McEnery Gwynn papers.

10 Shane Leslie to Audrey Morris (18 June 1950) – Leslie papers in Georgetown University Library, Washington D.C.

11 Leslie MS.

Acknowledgments

This book is the culmination of over five years’ work and would not have been possible without the help of a number of individuals, particularly those who saw the potential of this subject long before I began to write. Most of all I am indebted to Lady Lavery’s descendants who allowed me unlimited access to the Lady Lavery Collection. They afforded me hospitality on many occasions. Sadly, Hazel’s daughter, the late Alice Gwynn, did not live to see the publication of her mother’s biography, but I am happy in the knowledge that she knew I would write it.

I am grateful to the Hon. Edwina Epstein for allowing me to quote from an unpublished biography of Lady Lavery by her late mother, Lady Audrey Morris. The material gathered by Lady Audrey in the 1950s, and her insights into the personality of Lady Lavery and the period in which she lived, were invaluable.

I must particularly thank Dr Margaret MacCurtain O.P. for her encouragement. Her women’s documents course at University College Dublin sowed the initial seeds of this study.

For their advice and source material I am grateful to Eoghan Harris, Fr Brian Murphy O.S.B., Dorothy Ramm, Mary B. Hotaling, Thomas J. O’Gorman, the late Terence de Vere White, the late Sherrif Harold Ford and his wife Lucy, Lady M. E. Ford, Kenneth McConkey, Liam O’Gradaigh and Deirdre MacMahon.

I am indebted to the staff of the libraries and archives I consulted in Ireland, England and the United States. I extend my gratitude to Edburne Hare and the staff of The Masters School at Dobbs Ferry, New York; Seth Lampton of the Yale Club Library, New York; Barbara Parness at the Saranac Free Library; the staff of the New York Public Library and the New York Historical Society; the staff of the Newbury Library of Chicago; the Chicago Historical Society; Dale Louiso of St Chrysostom’s Church, Chicago; the staff of the Harry Ransom Humanities Center at the University of Texas at Austin, in particular Barbara Smith-La Borde; Nicholas B. Scheetz of Georgetown University Library, Washington D.C.; the staff of the British Library; the staff of the British Newspaper Library at Collingdale; the Tate Gallery Archive, London; the Public Record Office (England); Father Ian Dicky of the Westminster Diocesan Archives, London; Dr S.B. Kennedy of the Ulster Museum, Belfast; Seamus Heiferty and the staff of the University College Dublin Archive; Dr Meehan and the staff of the manuscript department of Trinity College Dublin; the National Archive (Ireland); the National Library of Ireland; Rachel O’Flanagan of All Hallows College Archive, Dublin; and Pat Cooke of Kilmainham Gaol Museum.

A number of people kindly granted me permission to quote letters, personal papers and published material. I wish to thank Martyn McEnery for allowing me to quote the writings of Lady Lavery and Mrs Alice Gwynn. For use of the Lady Gregory papers I acknowledge the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations; Tim Healy for permission to quote his grandfather; Tarka King for permission to quote his grandfather Sir Shane Leslie and his mother Anita Leslie King; Mary Semple for permission to quote Hugh Kennedy; the Society of Authors for permission to use unpublished material from George Bernard Shaw and Lytton Strachey; Peters, Fraser and Dunlop for permission to quote Evelyn Waugh; the board of Trinity College, Dublin, for permission to quote the R.E. Childers and Thomas Bodkin papers; Kit Orpen Casey for permission to use her father’s letters; Oliver D. Gogarty for permission to quote his father; and Kevin Rafferty C.M., Rector of All Hallows College, Dublin, for allowing me to quote from Fr Leonard’s papers. I regret that I was unable to contact those in possession of Ramsay MacDonald’s copyright.

I cannot say enough about the assistance given by my family: my sister Fiona, who was my dedicated proofreader; my mother, who brought me up to believe I could accomplish anything to which I set my mind; my brother Ciaran, who supplied technical expertise; and my fiancé Eamon Howlin, for supporting me throughout. Joe and Mary Talbot, the closest of friends, who helped me while I was researching and writing in America. For their editorial suggestions I thank Ann Marie Bennett, Carla Briggs, Jackie Clarke, Isabel Donnellan, Dolores Doyle, Anne Gormley, Bernard Guinan, Dr Brian Kennedy, Michael Kennedy, Donal and Marguerite Lynch, and Harriet O’Carroll. For their hospitality to me in New York and Chicago, I thank Patricia and Ned Trudeau, the late Dr Frank Trudeau and his wife Ursula, Kathleen Daniel, and John and Francis Shovlin. To those I have inadvertently overlooked, I extend my gratitude and apologies.

I am grateful to the staff of the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art, Dublin – in particular Barbara Dawson, Christina Kennedy, Dara O’Connell, Maime Winters and Liz Foster – and to the staff at the Lilliput Press – Antony Farrell, Vivienne Guinness, Brendan Barrington and Amanda Bell – for their support of this project.

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

The Lilliput Press is especially grateful to Eoghan Harris and David Dickson for their editorial advice.

I

‘The Most Beautiful Girl in the Midwest’

[1880–1903]

She had much Irish blood, but she was primarily an American. On the whole American women … are amazingly different from the others …. Their eyes are large and have a certain age-old gaze about them that makes one think that these women belong to the most ancient rather than the youngest of nations. Hazel was one of this kind.1

Edward Jenner Martyn and his wife Alice found it difficult to choose a name for their first child. The birth certificate issued for their daughter, born 14 March 1880 at 514 North Avenue in Chicago, bears no name at all. For the census in June they had settled on the name of Elsa.2 However, Elsa’s large brown eyes, which were to inspire artists and poets, prompted her parents to change her name to Hazel.3

Like many of his generation, Edward Martyn had left his home town of Attleboro, Massachusetts, and travelled west to seek his fortune. Chicago, on the shores of Lake Michigan, was a vibrant commercial metropolis, the centre of trade between the east coast and the advancing frontier of the western prairies. It had been almost completely rebuilt after the Great Fire of 1871, and by the turn of the century the city boasted the most important maritime port in the USA and the world’s greatest railroad centre.

Edward Martyn was first employed by Hugh McLennan & Co., a Canadian grain and commission firm.4 In 1875 he left the company to work as a messenger boy for Armour & Co., which, under the new management of Philip Danforth Armour, was to become the leading meat-packing firm in the country.5

Alice Louise Taggart was twenty-one when she married Edward Martyn, ten years her senior. She was the only surviving child of John (J.P.) and Susan Taggart, New Yorkers who had settled in Ripon, Wisconsin, where they owned a successful hardware business.6 By 1879 Edward Martyn’s ability had been recognized and rewarded, and he had become one of Armour’s chief advisors.7 The Martyn household was a happy one. Alice was affectionately known as ‘ha ha’, and Hazel’s earliest memory was the sound of her mother’s laughter.8

Although Hazel was close to her Taggart grandparents, it was her paternal ancestry that intrigued her. The Martins had ruled territory near Galway city on the west coast of Ireland between 1235 and 1300.9 They were descendants of Oliver Martin, a follower of the Norman conqueror Strongbow. After the Reformation a variation of the surname, Martyn, was commonly used. Although Edward Martyn’s ancestors settled in America in the seventeenth century,10 he took pride in his distant Irish pedigree and instilled in his daughter a love of Ireland.11 Hazel never forgot her father’s stories of how the Martyns had fought in rebellion.12 She treasured a bronze engraving of the Martyn coat of arms and often quoted the family motto, ‘Sicituradastra’ – ‘Such is the way to immortality’.

On 17 November 1887 Alice Martyn gave birth to a second daughter, Dorothea Hope. Dorothy, as she became known, was a pretty baby, with brown eyes like her father and sister, although her complexion was much darker. Even with the arrival of a second child, Hazel remained the dominant character in the family. Mr and Mrs Martyn idolized their vivacious elder daughter, who was already showing artistic and musical ability, and Dorothy was destined to spend her life in Hazel’s shadow.

By 1890 Armour & Co. was the largest meat company in the city, known for turning ‘bristles, blood, bones, and the insides and outsides of pigs and bullocks into revenue’.13 Edward Martyn was now Philip Armour’s right-hand man and Vice-President and Director of the Union Stock Yard and Transit Company of Chicago. One business associate recalled, ‘Wherever anything went wrong, Martyn was always the man to look after it.’14

Mrs Martyn and her daughters lived far from the squalor of the stockyards. They moved several times over the years, although never more than a few blocks from Hazel’s north-side birthplace. They lived at 71 Maple Street and 452 Dearborn Avenue before finally settling at 112 Astor Street in 1893, one of the most prestigious addresses in the city. The neighbourhood had been built on tracts of lake-side swamp land that had been drained and developed by the hotel magnate Potter Palmer.

The Palmers, the Wallers and the Hodges, prominent society families, became the Martyns’ closest friends. From 1890 the Martyn name featured in the ‘Blue Book’, the social register of Chicago which listed the city’s four hundred ‘gold coast’ families. Edward had little opportunity to enjoy his success, as he spent much time travelling within the United States and to Europe on business.15 Hazel’s imagination was fired by her father’s accounts of his travels.

In 1893, when Hazel was thirteen years old, the World’s Columbian Exposition was held in Chicago, bringing European treasures and millions of visitors to her home town. Exhibits included Columbus’s contract with Ferdinand and Isabella, jewellery from Russia and Gobelins tapestries from France. Years later Hazel recalled that nothing had encouraged her zest for wide horizons more than this spectacle.16

Early on, Hazel was taught at home by her mother. Her social education began with dance classes at Bourniques. She received instruction in music and drawing17 and was an avid reader. Her father once caught her with one of Louisa May Alcott’s books, TheRoseinBloom (1876), in which the heroine is forced to choose between suitors. Mr Martyn thought the novel too risqué and forbade Hazel to finish it. Her riposte appeared in verse:

When I’m dead and in my tomb,

You’ll wish you’d given me TheRoseinBloom.18

When Hazel outgrew her mother’s tutoring she was sent to Sleboth-Kennedy School at Bellevue Place, a private establishment catering to north-side society families, where she became one of the most popular girls.19 Her ‘most intimate friend’ was Ethel Hooper, the daughter of Dr Henry Hooper, a well-known Chicago physician; another friend was Marie Truesdale, whose family was one of the wealthiest in the city.

In her early teens Hazel moved on to Kemper Hall, a boarding-school for girls in Kenosha, Wisconsin. This tree-girt brick mansion facing Lake Michigan was a former home of Governor Durkee.20 Founded in 1870 and named in memory of the Reverend Jackson Kemper, the first missionary bishop of the American Episcopal Church, the school was only an hour from Chicago by train. Hazel must nevertheless have felt far from home, as there were no breaks during the school term and only one week’s holiday at Christmas.21

The school was run by the Sisters of Saint Mary, an Episcopalian order. Mother Margaret Clare, the headmistress, believed that the sisters’ aim should be ‘not simply to teach but to inspire’.22 Kemper Hall had a strict daily regimen. According to the 1874 Rules Book pupils rose at 6 a.m. and were to be in their dormitories by 9 p.m. Every girl was required to take a walk before breakfast, and the school organized competitions to encourage physical exercise. Students were divided into the houses of Lancaster and York, and wore the appropriate rose-badges.23 Competition was not confined to the sporting field; Hazel’s most abiding memory was winning the title of ‘The Most Beautiful Girl in the Midwest’.24

Why Hazel left Kemper Hall is not recorded, but by 1896 her name was on a waiting-list for a place at Miss Masters, a finishing-school in Dobbs Ferry-on-Hudson, New York. It was not uncommon in Chicago society for girls to be sent east, as the midwest was thought to lack the refinement of the established east-coast upper class. Hazel’s application stated that she was ‘exceedingly desirous of joining the school during that winter’ and that she would ‘go at a few hours’ notice if a vacancy should occur’.25

Miss Masters School was established in 1877 by the widow of the Reverend Francis Masters and her two daughters.26 Eliza B. Masters, the eldest daughter, was head of the school and its guiding force. The school followed Episcopalian and Presbyterian religious practices and the application form questioned whether the prospective pupil was a Church communicant. Bible-study classes and visits to the chapel were compulsory. This religious focus seems to have been in keeping with the beliefs of Edward Martyn, who had helped establish the family’s neighbourhood Episcopalian church, St Chrysostom’s, pledging the considerable sum of five hundred dollars towards the purchase of the church site.27 Thereafter he devoted what free time he had to his duties as church vestryman.

Hazel was accepted as a pupil at Miss Masters in September 1896. There were fewer than a hundred girls enrolled and lessons were oriented towards the individual student. The teachers were university-educated women who encouraged their pupils to be independent free-thinkers. Students were offered tuition in English, French and Latin, with music and art as extras.28 Hazel believed she should have been allowed to devote more time to music in her girlhood, later recalling, ‘my family had other views and made me concentrate on drawing, and that was that’.29

Besides singing in the Glee Club (founded after the Yale Glee Club had cancelled a performance in 1829 and the pupils pacified the crowd by dressing as men and performing impromptu), Hazel showed marked ability as an actress in a number of school productions. She was selected as one of ten honorary members of the Players Club, and many believed that she could have made a career in drama.30 Her talent was inherited from her father, who was known for his ability in parlour dramatics.31

In April 1897 Hazel had her first of several experiences of losing a loved one to a sudden death. Edward Martyn had taken some time off work with a cold, assuring his colleagues that he would soon return. His cold developed into pneumonia and he died within a matter of days.* His sudden death, attributed by many to overwork, shocked the community. Philip Armour, who had been visiting Astor Street at the time of Martyn’s death, was reported to be devastated.

Hazel was summoned home when her father became seriously ill, but he was dead by the time she arrived. The funeral had to be delayed for two days because Mrs Martyn was ‘prostrate with grief’. The burial at Graceland cemetery was a quiet family affair. The Taggarts came to stay with their widowed daughter and thenceforth lived at Astor Street. Hazel promptly went back to Miss Masters.

The school sheltered its pupils from the outside world and yet trained them to move in society with ease. It was close to New York City, and there were frequent outings for afternoon tea, the opera, the theatre and lectures. Miss Masters girls attended dances at Yale University and in turn Yale men attended those held at Dobbs Ferry. Hazel attracted many suitors,32 the most attentive being Edward Livingston Trudeau Jnr, eldest son of the eminent Dr Edward Livingston Trudeau Snr, founder of a tuberculosis sanatorium in the Adirondack Mountains in upstate New York. Ned had graduated from Yale Medical School in 1896 aged twenty-three, and was studying at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York when he met Hazel. He was tall and athletically built, with a sallow complexion and dark hair, perhaps due to his French lineage.** At Yale Ned pitched for the baseball team33 and was a member of the Skull and Bones Society, a secret organization that accepted only the brightest and most talented of students. However, despite his attributes and great persistence in courting Hazel, Ned could not kindle her interest.

After graduation from Miss Masters in the summer of 1898, Hazel embarked on a visit to France. Little is known of this European sojourn but she must have been to Paris. The late 1800s saw the climax of ‘labelleépoque’, as new theories and practices in art developed around artists such as Edouard Manet, Claude Monet and later Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin and Vincent Van Gogh. Turning from traditional academic painting, some artists looked to contemporary life, and others depicted the landscapes surrounding them. Painting enpleinair, they sought to capture the play of light and shadow using a greatly brightened palette. Artists exchanged ideas and gathered in the studios and cafés of Paris, and in the villages of Brittany, Normandy and the environs of Fontainebleau.

American artists flocked to Europe at the time. One of these, William Merritt Chase, claimed he would ‘rather go to Europe than go to heaven’.34 Wealthy female students, often denied a thorough artistic education at home because of their sex, sought private instruction in the studios of more liberal male painters and sculptors in Paris.35 Hazel spent almost a year abroad and she later mentioned visiting Rome and the French Riviera. She loved Europe and there found an artistic atmosphere unlike anything she had known in America.36

Back home in Chicago, steel-framed skyscrapers were punctuating the skyline, and the elevated Loop transport was completed in 1897. Developers had no wish to preserve older buildings and Hazel, who loved the past, greeted these changes with little enthusiasm. She would later exclaim that the USA stood for ‘the most hopeless modernity and vulgarity’.37

In the winter of 1899 Hazel came out in Chicago society. That season saw the largest number of debutantes ever, and society columnists enthused that it promised to be the gayest in years.38 The social calendar was filled with dinners, luncheons, cotillions and opera parties. Hazel’s debutante reception was held at the family home at Astor Street on the evening of Saturday 11 November, and several hundred callers came to inspect the young Miss Martyn in her gown of white organdie.39 Ethel Hooper, Marie Truesdale and Rue Winterbotham were among the twenty-eight girls who assisted her. It was a modest affair compared with Marie’s debut, which featured a reception at the Fine Arts Building for 500 guests and a ball for 200.40

Hazel’s name soon began to appear regularly in the society columns. Contemporaries described her as an astonishing beauty, with immense presence despite her five-foot two-inch stature. Her small, rather pointed face was dominated by lustrous almond-shaped hazel eyes.41 Despite these attractions, the educated, artistic and beautiful Miss Martyn did not have a steady beau, though Ned Trudeau continued ‘to worship at the Martyn shrine’.42

The Martyns spent lavishly on clothing and entertainment, though the family fortune had dwindled since Edward Martyn’s death. His estate had amounted to $100,000, with $75,000 invested in personal property.43 The house on Astor Street proved too expensive to maintain and by the winter of 1900 it was necessary to sell. The Martyns moved into the luxurious Virginia Hotel, which rented suites to long-term guests. Alice Martyn, anxious to continue to provide for her daughters in the manner to which they had become accustomed, began to borrow money from Armour & Co.44

The family was now without a permanent residence in Chicago, and spent much of 1901 and 1902 in Europe. Hazel sought the company of artistic people wherever they travelled. During the summer of 1902, her mother and sister stayed in Chicago while she returned to Paris to study etching, an art-form that was undergoing a revival.45 Hazel was tutored in the dry-point style, and by the end of her stay had amassed a large portfolio. When she returned Hazel gained a reputation as one of the cleverest amateur artists in Chicago.46 A realistic self-portrait in watercolour and gouache entitled ‘Convalescence’, with its subject propped up on pillows, wearing a lacy bed-jacket and cap, dates from this period (see plate).

In the spring of 1903 Hazel exhibited her European work and received notices from the critics; the ChicagoDailyNewsreported, ‘Men who know pictures are enthusiastic over her work.’47 One journalist compared her etchings to those of the French artist Heileu.48 That year the Arts Collectors’ Club sponsored the publication of a book of six of her sketches of women (see plate). Hazel announced that she intended to study art: ‘I am so anxious to be taken seriously. My friends have known nothing of my aspirations.’49 At a time when many female artists were exchanging marriage and domesticity for professional careers, Mrs Martyn accepted Hazel’s artistic ambitions, at least until a suitable husband could be found.

Notes

1 Lavery, Life, pp. 195–6.

2 The census of 1880 for Cook County, Illinois.

3 Lady Audrey Morris’s unpublished biography of Lady Lavery (herein Morris MS), p. 26.

4TheChicagoTribune (13 April 1897), p. 4.

5 E.R. Prichard (ed.), Illinoisofto-dayanditsProgressiveCities (Chicago n.d.), p. 19.

6 I am grateful to Thomas J. O’Gorman for this reference.

7TheDailyOcean (13 April 1897), p. 4.

8 Morris MS, p. 27.

9 G.V. Martyn to Hazel Lavery (May 1923) – LLC.

10 I am grateful to Thomas J. O’Gorman for this reference.

11TheChicagoTribune, Sunday supplement (30 April 1950), p. 5.

12 Hazel Lavery to Lytton Strachey (3 December 1928) – Strachey papers in the British Library, London (MS 60676).

13 Roger Butterfield, TheAmericanPast (New York 1966), p. 315.

14TheChicagoTimes–Herald (13 April 1897), p. 5.

15Ibid.

16 Morris MS, p. 34.

17Ibid., p. 28.

18Ibid. p. 29.

19TheChicagoDailyJournal (4 May 1904), p. 4.

20KenoshaEveningNews (25 May 1917).

21KenoshaNews (11 November 1973).

22KenoshaEveningNews (21 May 1970).

23KenoshaNews (3 November 1945).

24 Alice Gwynn to author (10 November 1990).

25 Hazel Martyn’s application to the Miss Masters School, Dobbs Ferry, New York.

26TheAlumnaeRecordoftheMissMastersSchool (New York 1913), p. 25.

27 The Minute Book (1894–7), St Chrysostom’s Church, Chicago, Illinois.

28 The school fees amounted to $1149.71 between September 1897 and June 1898. The Martyns were billed $70 for Hazel’s singing lessons and $12 for her use of the school piano. (The School Ledger 1897–8, Miss Masters School, Dobbs Ferry, New York).

29 Unidentified press cutting (undated 1930s) – Lady Lavery’s scrapbooks – LLC.

30 Alice Gwynn to author (10 November 1990).

31TheDailyOcean (13 April 1897), p. 4.

32TownTopics (12 May 1904), p. 9.

33 Edward Livingston Trudeau, AnAutobiography (New York 1916), p. 272.

34IndianapolisStar (14 January 1899), p. 9, quoted in John Wilmerding, AmericanArt (Middlesex 1976), p. 144.

35 Whitney Chadwick, Women,ArtandSociety (London 1990), p. 197.

36TheSundayInterOcean (25 July 1909), p. 6.

37 Hazel Trudeau to John Lavery (2 May 1905) – LLC.

38TheChicagoTribune (26 November 1899), p. 42.

39TheSundayInterOcean (12 November 1899), p. 18.

40TheChicagoTribune (12 November 1899), p. 37; (29 November 1899), p. 17.

41 Lady Anita Leslie reminiscences in the possession of Eoghan Harris, Monkstown, Co. Dublin.

42TheChicagoRecord–Herald (22 July 1909), p. 1.

43TheChicagoTribune (17 April 1897), p. 9.

44 The last will and testament of Alice Louise Martyn – Probate Office, Chicago City Hall.

45TheChicagoTribune (30 May 1902), p. 13.

46TheChicagoInter-Ocean (25 July 1909), p. 6.

47 Thomas J. O’Gorman, ‘Madonna at a Bullfight’, in TheWorldof Hibernia, Vol.1, No.1 (Summer 1995), p. 169.

48TheSundayInter-Ocean (25 July 1909), p. 6.

49 O’Gorman, op.cit., p. 169.

* According to his death certificate he also suffered from nephritis, or Bright’s disease.

** The Trudeau family emigrated from France c.1838 and settled in New York.

II

‘most great and wise and solemn John’

[1903]

Before Hazel’s book of sketches was published, she returned to France with her mother and sister, spending the summer of 1903 at an artists’ colony in Brittany. Situated on a headland on the Breton coast between the villages of Concarneau and Pont-Aven, Beg-Meil had quiet shady beaches, rocky coves and dunes, and had been the haunt of Impressionists and Post-Impressionists over the previous forty years.1 The destination was chosen by Hazel, who wanted to learn the techniques of Impressionism.

The Martyns’ entrée to the artistic world of Beg-Meil was an Anglo-French-American artist, John Milner-Kite. Mrs Martyn had commissioned him to paint her daughters, and he had completed Dorothy’s portrait and was struggling to depict Hazel when he enlisted the help of John Lavery.2

An established painter who had frequented Brittany since 1883, Lavery was born in Belfast in 1856,* the second son of Henry Lavery, a successful Catholic wine merchant. Three years later, the wine trade declined and Henry set sail for New York in search of new fortune, leaving his wife Mary and three young children behind. Disaster struck when his ship, the Pomona, was wrecked off the coast of Wexford and he was drowned. Three months later Mary Lavery, too, was dead.3 The orphaned children were sent to live with relations. John Lavery was brought up by an aunt and uncle in Moira, Co. Antrim, and later by another relation in Ayrshire, Scotland. When he came of age, Lavery moved to Glasgow and worked in a photographer’s studio retouching prints. This enabled him to attend art classes. He later acquired a studio of his own and struggled to establish himself as a painter. Ironically, it was only when his studio burned down that, using the insurance money, he could finally afford to study seriously – first in London and later in Paris.4

In 1885 Lavery returned from Paris and formed the ‘Glasgow School’ with James Guthrie, E.A. Walton and Joseph Crawhall, promoting modern French techniques in Britain.5 His work began to earn critical praise and ‘A Tennis Party’ won him a bronze medal in the Paris Salon of 1888. Lavery then received a number of key commissions, the most important being to commemorate Queen Victoria’s visit to Glasgow in August 1888 for the International Fine Arts Exhibition. The painting took two years to complete and involved 250 separate portrait sittings.6 Though not a critical success, the studies helped develop his skill as a portraitist, and he became known for his flattering depictions of women.

At Beg-Meil Lavery was only too glad to show off his talent, ‘especially before such loveliness’; he, too, was captivated by Hazel Martyn.7 She now wore her red hair in a top knot, accentuating her small face and large brown eyes.

Hazel had first noticed Lavery from her seat on the hotel’s veranda, as he struggled past with a six-foot canvas strapped to his back.8 He was short in stature with a stocky build, and not particularly handsome. For Hazel, however, he was the embodiment of Beg-Meil’s heady bohemianism and all that she was seeking in Brittany. She considered him a master painter, and to his delight treated him with the greatest respect and admiration,9despite the fact that her portrait, the combined effort of Lavery and Milner-Kite, was not a success. Perhaps to redress this failure, John made a cartoon sketch of himself with a turned-up nose while Hazel drew a self-portrait beside it (see plate).10

In the evenings Hazel joined Lavery and Milner-Kite in animated conversations on art, while Dorothy ignored them and read. Her introversion contrasted sharply with her sister’s exuberance, and though there was a striking physical resemblance,11 Dorothy’s large brown eyes were marred by the sadness that would eventually consume her.

Milner-Kite described Hazel’s mother as ‘the old Chicago dame’, referring more to her attitude than her age; at forty-five she was two years younger than Lavery. She was not favourably disposed to ‘bohemians’ and was upset to find her daughter engaged in such spirited conversations, particularly with Lavery. He was a widower with a teenage daughter, and twenty-four years Hazel’s senior; even worse, he travelled with an attractive young German, Mary Auras, the model for several of his well-known paintings.* A young Irishman, P. Burrowes Sheil, also accompanied Lavery to help amuse Mary and, as Lavery wrote in his autobiography, to ‘share the scandal, if there should be one, of my taking a beautiful girl to the country for months at a time’.12 Regardless of this precaution, Mrs Martyn was convinced Lavery was a wholly unsuitable companion for her daughter. These were not the sort of people whom the Martyns had travelled to Europe to meet.

Lavery was not Hazel’s only admirer in Beg-Meil. Pompey Howard had followed her from Paris to advance (as Lavery smugly wrote later) ‘his unsuccessful attentions’.13 Hazel had never been in love and played romantic and emotional games with relish. She initially believed she was only ‘sentimentally interested’ in John,14 but soon realized that he was different. On the third day of their acquaintance, John escorted Hazel to the nearby village of Pont-Aven, set in a romantic valley between two thickly wooded hills, where Gauguin had often painted. Here, Hazel first professed her feelings for John, and she would later write:

And you are not to mention the ever (to me) embarrassing fact that it was I who was the first to discover – Oh! well the fact that you wanted me to come into your garden.15

The ‘garden’ was to become the dominant motif of their love letters.

Mrs Martyn was unaware that her daughter had fallen in love. But Hazel admitted to John: ‘You were not so clever to fall in love in three days after all. Why even I did that! and what is more did it much more completely and thoroughly than you.’16

The Martyns left Beg-Meil for Paris a few days after the Pont-Aven trip and John followed shortly after. He invited Mrs Martyn, Hazel and Dorothy to have lunch with himself and Sheil at their hotel on 24 September. The meal was a disastrous affair, and Mrs Martyn remained convinced of John’s shortcomings as a suitor. He departed for London the following day with Hazel’s promise to write. Her first surviving letter was written three days later to ‘Dear dearer dearest and all sorts of other love names John’:

… I am still in your garden still incorrigibly and unwarrantedly and unconcernedly sitting in the middle of your best flower bed just as though I had been properly invited! … I have one eye on the gate of your garden John. You were foolish to leave it unlocked but perhaps you did that purposely.17

It had been many years since John Lavery had last been in love. His first wife, Kathleen, was ill for most of their short marriage. She suffered from tuberculosis and died only a few months after giving birth to their daughter Eileen.18 Now, John was acutely conscious of the age difference. His reply expressed a fear that she would soon tire of him:

Well dear I am busily engaged in looking for the key and wondering how you would feel to be locked up in such an old garden with all the flowers to tend and the funny old paths to keep straight and if you wouldn’t after a time get tired and want to climb the wall and get out one fine morning and leave it to ruin?19

The couple were anxious to be reunited. From London, John began making plans for Hazel to visit him, perhaps in October, ‘usually a delightful month’. He busied himself with enquiries about hotels and lessons for Hazel in dry-point etching.20 He wished to paint Hazel again, this time in his South Kensington studio rather than in France, because he feared that ‘working in a strange studio against time’ might produce another failed portrait.21

When ‘most dear decided Mamma’ refused to go to London, Dorothy was ‘popped’ into boarding school, and Hazel enrolled with Edgar Chahine22, an etcher with a reputation for depicting the Parisian masses, though her interest in dry-point etching was fading. John urged Hazel to take advantage of her classes and suggested that she exhibit some well-known person’s portrait at the new Society of Portrait Painters’ gallery in London. The committee had asked Lavery to select a piece worthy of exhibit. John thought Hazel’s self-portrait, ‘Convalescence’, ‘really most charming’ (seeplate).23 The suggestion was not welcome and Hazel protested that he was not attuned to her ‘chaotic volcanic frame of mind’. Of her lessons, she declared she could not calmly draw flowing lines upon her beloved copper plates, but ‘mutilated the dear things’ in her agitation. She chided, ‘I suppose that you will attribute all this to a becoming and seemly maiden hesitation.’24

The balance had been established, John the realist, Hazel the romantic. The steadfastness of the ‘most great and wise and solemn John’25 attracted her, calming and tempering her melodramatic nature. During their separation, Hazel’s thoughts had returned to their customary ‘wild, vivid, primitive intensity’.26 On 11 October, two weeks after John left Paris, she wrote:

It has caught me now John Lavery, the storm and panic. All my fine recklessness and gay courage is gone. I am even no longer incorrigible! It is my turn to beg ‘Wait wait I must have time.’ I am only a girl who is afraid to become a woman. And I am alone. I belong to nothing or no-one in the world – I could not bear to belong – and yet the very thought of giving myself is terrible and sweet. If I dared.27

John delighted in her reaction as ‘right and proper and just as it should be’.28 He trusted that any difficulties could be overcome and that Hazel would be his wife.

I believed that [you] alone of all those who had ever been in or near the garden knew and understood, and the mists cleared, and what was vague and uncertain has become clear and defined. And behold here am I John knocking at your gate Hazel dearest. And so the sovereign right of she whom I call wife is asserted, and this tradition and principle remain undisturbed.29

There was extreme tension between mother and daughter by the end of October. Mrs Martyn thought Hazel ‘absolutely mad’ to want to travel to London, knowing so little of John Lavery. Hazel continued to plead; she wrote to John that ‘you may be sure I begged to go … it seemed the only way’. Mrs Martyn held fast. Hazel worried that family strife would be worse in London, bringing aggravation and stress to John, who asked of her only peace.30

No Hazel! just the other way round, it would be madness and lunacy not to come. Do please trust yourself. I know how difficult this is for one so young and so impulsive but if you will just look through the proper end of the telescope you will find me right in the foreground – not withstanding the charm that distance may give – ready to take some small share of a responsibility that the little Hazel thinks is all her own. It must be obvious to the mother that vague and misty misgivings – if they cannot be removed by coming to London, they can at least be made clear. It is not a question of knowing each other – that we do know – no; it is of knowing ourselves, and as I have told you my problem is solved and as far as human thought goes or my poor brain can travel, the road seems clear. Of course it is easy for me after all these years to know when I have reached my haven. It is not so easy for you, but we will take all the time you desire and there shall be no undue haste.31

John awaited Hazel’s telegram, but her mother sent one instead: ‘Very sorry but impossible to go to London.’32 She elaborated in a letter:

It was no idle decision that I sent by telegram this morning – Hazel is really a wreck and I am unnerved over the worry and anxiety this question has caused us – I alone am to blame for not going up to London and though the inducements in every way serious and otherwise are great I simply cannot let her go now – the situation is sudden and tremendous. I do not want to trust the added glamour of the atmosphere there would be in seeing you in your own attractive home. That Hazel cares a great deal for you there is no doubt but it is the question of her lifetime. She must go slowly. In every way she is disappointed in not going to London and I may be very very wrong – I have only the child’s happiness at heart and I am doing what seems to me right -I will not try to say the conventional thing it seems too trite. I hope you will believe that I am doing what I feel will be best for the happiness of you both.33

Her authority undermined by the continued correspondence between Hazel and John, Mrs Martyn now resorted to more drastic measures. She cabled Ned Trudeau in the second week of October. The message was plain: ‘Come quick or you’ll lose Hazel.’ Ned hastily packed for the journey, so anxious to make the first available sailing that he left without his overcoat.34

Unaware that Trudeau had been summoned by her mother, Hazel wrote to John: ‘To complicate matters there arrives in Paris from America the one man in the world who the dear Mamma would not think me more than mildly insane to marry.’ Hazel now confined herself to a ‘darkened room – eau de cologne and tears’. She described herself as ‘behaving quite like the languishing heroine of an early English novel when her love affairs grew too distressing’.35

Mrs Martyn and Ned Trudeau, determined to make Hazel forget Lavery, arranged to return to America immediately. Hazel, knowing her mother’s determination, wrote pessimistically to John: ‘I am very helpless more helpless indeed than you can know.’ They planned to sail within the week: ‘I cannot breathe when I think of crossing that dreary sad gray ocean.’36

John now rushed to Paris to claim Hazel’s hand, arranging to see Mrs Martyn without her daughter. Indignant at her exclusion, Hazel warned John not to mention their intimacy at Pont-Aven: ‘I shall never forgive you if you told Mamma how bold I have been.’37

Lavery’s meeting was unsuccessful and he went back to London. The Martyns and Ned Trudeau set sail for New York on 1 November, on board the Pennsylvania from Boulogne. Hazel still hoped that she could convince her mother that her feelings for John were more than an infatuation bred by the romance of France. She shut herself in her cabin and refused to speak for the first week of the voyage.38 By the time the ship reached New York fifteen days later, it had been decided that Hazel was to marry Trudeau without further delay. There was little to do but consent.

Ned Trudeau was now thirty and had devoted himself to his medical career. Having been president of his class in the College of Physicians and Surgeons, then house surgeon in the Presbyterian Hospital in New York,39 Ned joined Dr Walter B. James’ successful practice in New York City in the autumn of 1903.

Upon arrival, Hazel and Ned travelled to Saranac Lake, New York, a remote town in the Lake Placid region of the Adirondack Mountains, to meet Ned’s parents. Ned’s father recalled years later: ‘It was love at first sight, and a violent love affair with Ned, and when she went abroad he left us suddenly, went to Europe, and must have carried the fortress by storm, for he soon returned in the same ship with Miss Martyn and her mother.’40 Dr and Mrs Trudeau and Ned’s younger brother Francis were staying at their hunting lodge deep in the woods.41 Hunting, sailing and swimming, the activities of Saranac Lake, underscored Hazel’s feeling that she had little in common with the Trudeaus. It was all so different from Beg-Meil. On her return journey to Chicago, Hazel wrote to John, enclosing a photograph of herself:

Goodbye John Lavery – As I came into your life suddenly and without warning so I go and there is silence once more. For I must go and you must not cry out or lift your hand to bring me back – it is not to be – Let us forget – Before you read this I shall belong to Edward Trudeau utterly irrevocably. I may not tell you my reason and you shall not ask, this is at once a command and an entreaty. John Lavery believe in the truth of my every thought and word and deed toward you. There was no stain of falseness in there. Once you said it took a long long time to become young but one can grow old in a single hour. I am old and very tired. Please keep my letters. They are the real real Hazel you can remember her without bitterness – I have gone and again you are alone.42

John still harboured vague hopes that the wedding would not go ahead. He sent a forlorn telegram which arrived at the Virginia Hotel on 1 December: ‘Any Hope.’43 Two days later he cabled Mrs Martyn: ‘Please delay proceedings serious consequences have written.’44 Convinced that he must travel to America, the following day he sent a more frantic cable: ‘Her future happiness possess undoubted proof. Delay can injure nobody. May prevent grave mistake. Do consider. Sailing shortly.’45

Lavery’s appeals had no effect, and on 3 December Hazel released her wedding details. She would be unattended, save perhaps for her sister Dorothy; with no pre-nuptial entertainments, the wedding would be a simple one.46 The next day the social column of TheChicagoTribune told of how this news had disappointed her friends.47 Tales of a European romance were the subject of gossip in Chicago drawing-rooms and it was known that Hazel Martyn’s suitor had cabled for postponement until he could make his plea.48 John must have been convinced of the futility of sailing as the surviving correspondence gives no further indication as to why he never set to sea. He had always been thoroughly absorbed in his art, but as he wrote in his autobiography thirty-seven years later, ‘I then realized that painting pictures was not everything.’49

The wedding, held at noon on 28 December in St Chrysostom’s church, was not the planned quiet affair, but one of the most fashionable events of the season.50 While the guests were seated, an organ played old-fashioned airs. The society columnist for the Tribune wrote:

It was not unlike the bride, who is noted not only for beauty and popularity but also for her artistic taste in all things, to select such time-honoured songs as ‘Annie Laurie’, ‘How Can I Leave Thee’ and ‘Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes’ and instead of a modern love song as a setting for the holy words of matrimony a simple old German melody was softly played. With the coming of the bride, the wedding march from ‘Lohengrin’ was heard.51

Hazel entered the church alone. She wore a filmy gown of white tulle over shimmering white satin, with tiny white tassels on the sleeves and garlands of orange blossoms on the bodice and skirt; a coronet of buds held a long tulle veil. Instead of a bouquet, she carried a white prayer-book with a tiny sprig of orange blossoms held between the pages.52 Father Snively, a well-known preacher who had confirmed Hazel eleven years before, conducted the ceremony.53 Ned’s father later wrote, ‘I only repeat what I heard so many others say: that a handsomer couple than Ned and Hazel Martyn are not often seen.’54

The wedding, which had all the appearances of a perfect society match, represented for Hazel the loss of the man she loved and the life she craved. That morning, before the ceremony, she had written to John:

And this is my wedding day. I suffer. There is no such thing as joy or goodness or justice in this world and it is not true that hearts break they merely grow more keen with pain and ache ache through one’s whole life. It is not true that duty should be a primary consideration. It is not true that I shall know in future the mercy of God and see that all is for the best – nothing is true save that there is no hope for me how terribly hideously well I know this to be true. I am yours the soul and the breath and brain and bleeding heart of me are yours – and my life will be lived for you whether you will or no – and you shall think and long despair with me – always – always – always. No law can hold my soul. No human creature can touch me. I am yours. I shall write to you my hearts dearest. Nothing shall be hidden from you. All that is mine is yours and and (sic) in an hour they will put on my bridal gown. And do you know what is the most bitter of all the great and little bitter thoughts that stab my heart? It is the silly frivolous wish that you are not to see my beauty in it … I am a woman – once you told me that you loved me for it – and with a woman it is the little things that give most joy or pain. Your letter came this morning. God is indeed cruel to me. And I have nothing but bitterness in my heart. My love my best beloved do you suffer with me? or are you in your wisdom and greatness pitying me for my mad grief and unreasoning anguish. I am not a child. I am a woman and I have suffered as much as you have in your whole life – I know. Dear God I would go to you now proudly and gladly dear if I did not love you too well to hurt you and your love for me by such madness and folly. Dearest I wish my heart had stopped beating forever that night at Pont Aven. I remember how I trembled all the night through and prayed God to let me be happy and have my heart’s desire. I knew then that I was to suffer … I never dreamed how much. I love you supremely. I am not an ordinary woman and I do not love in an ordinary way.55

Notes

1 Richard R. Brettell, Scott Schaefer, Sylvie Gache-Patin, and Francoise Heilbrun, ADayintheCountry,ImpressionismandtheFrenchLandscape (Los Angeles 1984), p. 300.

2 Lavery, Life, pp. 128–9.

3 Kenneth McConkey, JohnLavery (Edinburgh 1993), p. 13.

4 Lavery, Life, p. 49.

5 Kenneth McConkey, JohnLaveryRetrospectiveExhibitionCatalogue1985 (Belfast 1984), pp. 23–5 (herein Catalogue).

6TheNewYorkTimes (13 January 1941) – LLC.

7 Lavery, Life, pp. 128–9.

8Ibid., p. 128.

9Ibid., pp. 128–9.

10 This drawing is in Lady Lavery’s scrapbooks – LLC.

11TheChicagoTribune (29 December 1903).

12 Lavery, Life, p. 128.

13Ibid., p. 129.

14 Hazel Martyn to John Lavery (27 September 1903) – LLC.

15 Hazel Martyn to John Lavery (29 October 1903) – LLC.

16 Hazel Martyn to John Lavery (27 September 1903) – LLC.

17Ibid.

18 Lavery, Life, p. 68.

19 John Lavery to Hazel Martyn (28 September 1903) – LLC.

20Ibid.

21 John Lavery to Hazel Martyn (undated, October 1903) – LLC.

22 Hazel Martyn to John Lavery (5 October 1903) – LLC.

23 John Lavery to Hazel Martyn (undated, October 1903) – LLC.

24 Hazel Martyn to John Lavery (15 October 1903) – LLC.

25 Hazel Martyn to John Lavery (5 October 1903) – LLC.

26Ibid.

27 Hazel Martyn to John Lavery (11 October 1903) – LLC.

28 John Lavery to Hazel Martyn (undated, October 1903) – LLC.

29 John Lavery to Hazel Martyn (24 October 1903) – LLC.

30 Hazel Martyn to John Lavery (24 October 1903) – LLC.

31 John Lavery to Hazel Martyn (undated, October 1903) – LLC.

32 Alice Martyn to John Lavery (23 October 1903) (1) – LLC.

33 Alice Martyn to John Lavery (23 October 1903) (2) – LLC.

34 Alice Gwynn to author (10 November 1990).

35 Hazel Martyn to John Lavery (24 October 1903) – LLC.

36 Hazel Martyn to John Lavery (23 October 1903) – LLC.

37 Hazel Martyn to John Lavery (29 October 1903) – LLC.

38 Alice Gwynn to author (10 November 1990).

39 Certificate in the Adirondack Collection – Saranac Lake Free Library, Saranac Lake, New York.

40 Trudeau, AnAutobiography, p. 274.

41 The Trudeau Little Rapids Visitors Book – Adirondack Collection – Saranac Lake Free Library, Saranac Lake, New York.

42 Hazel Martyn to John Lavery (15 November 1903) – LLC.

43 John Lavery to Hazel Martyn (1 December 1903) – LLC.

44 John Lavery to Alice Martyn (3 December 1903) (1) – LLC.

45 John Lavery to Alice Martyn (3 December 1903) (2) – LLC.

46TheChicagoTribune (3 December 1903), p. 17.

47TheChicagoTribune (4 December 1903), p. 21.

48TheChicagoRecord-Herald (22 July 1909), p. 1.

49 Lavery, Life, p. 130.

50TheChicagoEveningPost (28 December 1903).

51TheChicagoTribune (29 December 1903).

52Ibid.

53 Register at St Chrysostom’s Church, Chicago.

54 Trudeau, op.cit., p. 24.

55 Hazel Martyn to John Lavery (28 December 1903) – LLC.

* The precise date of Lavery’s birth is unknown. His baptismal certificate states that he was baptized on 26 March 1856.

* Mary Auras was the model for ‘Spring’ (Musée d’Orsay, Paris) and ‘Lady in a Green Coat’ (Bradford Art Galleries and Museums).

III

‘the siren calls’

[1904–8]

Your wit is inclined to many conversations, and you will do great mischief against your will, dangerous to others, therefore you will have bad luck.

–Fortune-teller’s prediction for Hazel, July 1905

The Trudeaus moved to 772 Park Avenue, an apartment house furnished by Ned’s parents as a wedding present with a small studio built for Hazel. Rather than the customary gift of diamonds or pearls, Hazel had asked for an etching press, which she described as the most precious gift she could have received. Ned and Hazel included visiting cards with their wedding invitations, opening their new home to guests after 1 February 1904.1