Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

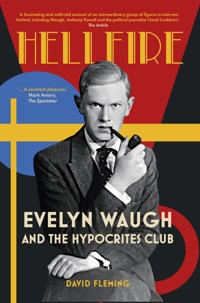

'This is a pacey and colourful read … elegantly written.' – Daisy Dunn, The Times 'The whole book reads rather like a Powell novel, with unexpected meetings and reversals … it is a constant pleasure.' – Mark Amory, The Spectator 'At a rollicking pace, it follows the post-Oxford careers of all the main Hypocrites … Waugh addicts will wish to add it to their shelves.' – A.N. Wilson, Times Literary Supplement Daily Mail top ten history book of 2022 Described by one habitué as 'a kind of early twentieth-century Hell Fire Club', the Hypocrites Club counted some of the brightest of the future 'Bright Young People' among its members. The one-time secretary was Evelyn Waugh, who used ten of his fellow Hypocrites as inspiration for his fictional characters – seven of them in Brideshead Revisited alone. The Hypocrites didn't just lend themselves to Waugh's fiction. Many went on to prominence themselves, including Anthony Powell, Robert Byron, Henry Green, Claud Cockburn and Tom Driberg. Hellfire is the first full-length portrait of this scandalous club and its famous members, who continued to be thorns in the Establishment's side – throughout war and austerity – for the next five decades.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 560

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Under various aliases David Fleming was formerly a documentary filmmaker specialising in music, arts and history programmes, and is currently a writer and journalist. His articles have appeared in The Guardian, The Independent, The Daily Telegraph and The Article.

For Matthew and Emily

Front cover illustration: English novelist Evelyn Waugh (1903–1966). (© Bettmann/Getty Images)

First published 2022

This paperback edition first published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© David Fleming, 2022, 2024

The right of David Fleming to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 220 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologie

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

1 Riotous Assembly

2 Sweet City

3 The Eton Society of Arts

4 Oxford Aesthetes

5 The Pursuit of Love

6 Life after Oxford

7 Chancing It

8 Forward March

9 Public Lives

10 On the Rocks

11 Pack My Bag

12 The Roads Less Travelled By

13 Love in a Cold Climate

14 A Low Dishonest Decade

15 First Byzantium then Oxiana

16 The Days of The Week

17 Appeasement and Der Pakt

18 The Phoney War

19 Into Action

20 Sword of Honour

21 A Twitch upon the Thread

Postscript: Portraits of the Artists in Middle Age

Bibliography

Notes

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank my agent, Andrew Lownie, for his indefatigable efforts on this book’s behalf. My thanks too to Mark Beynon, Alex Boulton and Katie Beard at The History Press for their work in shepherding it to publication. I am grateful to the staff of the British Library and London Library.

Nick Burstin, David Herman, Susie Herman, Alastair Laurence, Susan Lee, Jill Meager, Caroline Page and Barnaby Spurrier kindly read and commented on work in progress. Any mistakes, misunderstandings or misconceptions are of course my fault alone.

I would like to thank my wife, Helen Walker, for her support throughout the writing of Hellfire.

Copyright in quotations © resides with the publications referred to in the Notes from page 263; and with the Estates of Sir Harold Acton, John Jacob Astor VII, W.H. Auden, Patrick Balfour (3rd Baron Kinross), Hilaire Belloc, Sir John Betjeman, Sir Maurice Bowra, Robert Byron, Dudley Carew, Claud Cockburn, Patricia Cockburn, Cyril Connolly, Nancy Cunard, Cecil Day-Lewis, W.F. Deedes, Tom Driberg, Daphne Fielding (née Vivian, Marchioness of Bath), Ann Fleming, Michael Foot, Brian Franks, Terence Greenidge, Alannah Harper, Sir Roy Harrod, Christopher Hollis, Brian Howard, Christopher Isherwood, James Lees-Milne, Lady Dorothy Lygon, Erika Mann, Klaus Mann, Nancy Mitford, Ivan Moffat, Malcolm Muggeridge, V.S. Naipaul, Evelyn Nightingale (née Gardner), Pansy Pakenham (Lady Pansy Lamb), Anthony Powell, J.B. Priestley, Peter Quennell, Maurice Richardson, A.L. Rowse, Bertrand Russell, Dame Edith Sitwell, Frederick Smith (2nd Earl of Birkenhead), John St John, Christopher Sykes, A.J.P. Taylor, Alan Watkins, Alec Waugh, Auberon Waugh, Evelyn Waugh, Emlyn Williams and Henry Yorke (Henry Green).

Excerpts are reprinted by permission of © The Atlantic, Faber and Faber Ltd, Grand Street Publications Inc, John Murray (Publishers) Ltd, Hachette UK Ltd, HarperCollins Publishers Ltd, Hodder and Stoughton Ltd, New Statesman, Pan Macmillan Ltd, Penguin Random House Ltd, Quartet Books Ltd, The Spectator and Telegraph Media Group Ltd.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders. If any errors or omissions have been made, the author will be happy to make corrections in future editions, if the copyright holders in question care to get in touch via the publisher.

Spellings of places and names have been modernised, or their modern equivalents given.

1

RIOTOUS ASSEMBLY

The stamping ground of half my Oxford life and the source of friendships still warm today.

(Evelyn Waugh, A Little Learning, 1964)

On the evening of 8 March 1924, a young nun was seen by the porters of Balliol College, Oxford, trying to pass in just as the gates were due to close. Balliol was an all-male establishment and visits by young women were rare, especially by those belonging to a religious order. The nun turned out to be an undergraduate called Arden Hilliard, the son of the college bursar. He was coming back from a fancy-dress party held at a drinking club on the outskirts of the university district. At the Victorian-themed event, members had dressed as the late queen herself, choir boys in vermilion lipstick, ladies in crinoline, flower maidens and Madame de Pompadour, the official mistress of Louis XV.

The Hypocrites Club, already known for its heavy drinking and raucous noise, was then closed down, mainly at the urging of Balliol’s dean, long an opponent. This was the end of a remarkable, if short-lived, institution which began sometime in 1921 – no one is quite sure when. The club’s motto, taken from the first line of Pindar’s Olympian Odes, was ‘Water is best’: ἄριστον μὲν ὕδωρ. Its members’ indifference to this advice gave the club its nickname.

In his autobiography, Evelyn Waugh wrote, ‘It seems that now, after the second war, my contemporaries are regarded with a mixture of envy and reprobation, as libertines and wastrels.’ This was just as true in the 1920s, and the annals of the Hypocrites Club would tend to support this perception.

The great majority of its members – all of whom were men – were upper gentry or bourgeois, along with a few of the bolder aristocrats. Most of them, in the later stages of the club’s existence, came from Eton. The Hypocrites were rich, or lived beyond their means. The most prominent example of the latter group was Waugh himself, who left Oxford heavily in debt. Many of them went on to be successful and prominent in later life. They included the ‘English Proust’, Anthony Powell, the author of the novel sequence A Dance to the Music of Time; a cult modern novelist, Henry Green; a much-admired travel writer, Robert Byron, whose masterpiece The Road to Oxiana was compared in its influence to Ulysses and The Waste Land; and a political reporter whom Graham Greene called one of the two leading English journalists of the century, Claud Cockburn. His journalistic motto was ‘Believe nothing until it’s been officially denied’.

Tom Driberg, too young to be a member per se but a visitor who left a memorable account of an evening spent there dancing, founded Britain’s most famous gossip column, ‘William Hickey’. He was one of three habitués who became MPs. Three others became professors. Peter Quennell became a prolific author and reviewer, one of the founders of History Today. Alfred Duggan, described by Waugh as ‘a full-blooded rake of the Restoration’, sent down from Oxford, went on to have the most surprising career of all.

Other Hypocrites live on in the shadows of Waugh’s fiction. Two of the most prominent personalities, Harold Acton and Brian Howard, became the basis for one of his most brilliantly drawn characters, Anthony Blanche. Howard was also the model for Waugh’s Ambrose Silk in Put Out More Flags. Four Hypocrites influenced the character and circumstances of Sebastian Flyte in Brideshead Revisited. Gavin Henderson, the model for Lord Parakeet, who first appeared in Decline and Fall, converted his Rolls-Royce into an ambulance for Republicans wounded in the Spanish Civil War, and once addressed the House of Lords as ‘My dears’. Two regular visitors, and possibly members – record keeping was not one of the club’s strengths – jointly became Basil Seal, first encountered in Black Mischief.

The wealthy bluebloods and bohemians Waugh met at the Hypocrites Club didn’t just provide literary models: they became friends, enemies, rivals and lovers. If Waugh hadn’t passed into their world, Brideshead Revisited could not have been written. It was thanks to his membership of the club that the solidly bourgeois Waugh, from an unfashionable area of London, Golders Green, an unfashionable public school, Lancing, and an unfashionable college, Hertford, was able to gain an entrée into the aristocratic world he fell in love with and wrote about for the rest of his life. And very much part of this world were the Hypocrites’ mothers, sisters and female friends and cousins, some of whom found their way into Waugh’s fiction too. Less so into his bed, to his great frustration.

Of course, there is nothing unusual about a group of men living it up at university, on tick, or at their parents’ expense, and spending little time on their studies. Nor is there anything unusual in their remaining friends – or falling out – over fifty years, acting as each other’s best men or godfathers to their children or mourners at their funerals. Nor is there any great mystery about the later eminence of many members of the Hypocrites Club. Most did very badly academically at Oxford, and most deserved to. But the great majority of the Hypocrites were not, fundamentally, frivolous or idle individuals. They were, as Anthony Powell remarked, ‘a collection, most of them, of hard-headed and extremely ambitious young men’.

They were also highly intelligent and well educated – at least, up until the point when they arrived at the university and from the point they left. They were very well connected. They were self-confident, and far from diffident in pushing themselves forward, Robert Byron in particular. They acted as a mutual aid club, regularly praising each other’s work in reviews and puffing each other up in gossip columns. They were talented, some very much so. Why would they not succeed?

So, I do not suggest that the Hypocrites Club in some way catalysed these men’s future careers, in the startling way that being debagged set Paul Pennyfeather on a completely unexpected course in Decline and Fall. If there was something ‘in the water’, it went undrunk, despite the club’s motto.

But there is something about the Hypocrites Club that was special, or so it seems to me. So many of its members, different from each other in so many ways, set themselves apart from the prevailing ethos of their time. They were an awkward squad, certainly as young men, taking nothing at face value, impatient with the strictures of authority and outmoded social niceties. They shared a hatred of cant and received wisdom, and were always happy to rock the boat and bite the hand that fed them. They were pugnacious, to the point of being unhinged in the case of Byron and Waugh. They were not shy of causing offence, including to each other. Waugh was well known to be a bone-dry Conservative and ultramontane, to the point of self-caricature. Others, notably Claud Cockburn, remained firmly on the left.

The Hypocrites were born between 1903 and 1905. The last standing, Anthony Powell, died in 2000, at 94 years of age. All lived through the Great War, the party years of the ‘Bright Young People’, the Wall Street Crash, the Great Depression, the Spanish Civil War, Appeasement, the Nazi–Soviet Pact. All took part in the Second World War in one way or another, the majority in uniform. Most of them lived through austerity, the Cold War and the Swinging Sixties. All saw the decline of the aristocratic world familiar to their grandparents. Many were gay and lived through the years of odium and repression. The novels and autobiographies of Evelyn Waugh, Anthony Powell and Henry Green, three of the most important prose writers of their time, the memoirs of Claud Cockburn and Harold Acton, the letters of others, and the reminiscences of dozens of people who knew them, give a compelling if idiosyncratic insight into the events and the times through which they lived.

The Hypocrites Club – Peter Quennell described it as ‘a kind of early twentieth-century Hell Fire Club’ – had its premises in a ramshackle building at 131 St Aldate’s, south of Christ Church. Anthony Powell remembered that it consisted of ‘two or three rooms over a bicycle shop in an ancient half-timbered house at the end of St Aldate’s, where that long street approached Folly Bridge, a vicinity looked on as somewhat outside the accepted boundaries of Oxford social life’. The building was demolished in the 1960s. Confusingly, two rival street numbers have been cited in various sources. Perhaps the large amounts of alcohol consumed at the premises fogged the memories of the diarists concerned.

Henry Yorke, who wrote novels as Henry Green, said that it ‘had its rooms in the slums of the town. The reason why it was out of the way in one of those back streets must have been that the members made so much noise. It was a drinking club but was more, in the terrific roar of its evenings, the quarrels the shouting and extravagance. It was a sign of the times.’ ‘I cannot describe the place any further because on all the occasions I went there afterwards I never was sober once.’ But Claud Cockburn, Evelyn Waugh’s cousin, sums it up most succinctly of all. The Hypocrites Club was ‘a noisy alcohol-soaked rat-warren by the river’.

All agree that the club began as something of a high-minded enterprise. Undergraduates were, officially, forbidden to go into pubs. It seems generally held that the founder was a Welshman, John Davies Knatchbull Lloyd – always known as ‘The Widow’ after a well-known shaving unguent marketed as ‘The Widow Lloyd’s Euxesis’. Early members included the future novelist L.P. Hartley, author of The Go-Between, and Lord David Cecil, later a famous don. Anthony Powell was told that at its inception it was ‘relatively serious and philosophy-talking’. Its household gods were the poet Robert Graves (also author of Goodbye to All That and I, Claudius), who then lived in the fashionable bohemian enclave of Boars Hill, and Richard Hughes, writer of A High Wind in Jamaica, an undergraduate at Oriel.

Evelyn Waugh remembered the founding fathers as ‘heavy-drinking, rather sombre Rugbeians and Wykehamists with vaguely artistic and literary interests’. The Widow Lloyd was at Winchester; Terence Greenidge, who first introduced Waugh to the club, was at Rugby. Waugh remembered ‘a rich smell of onions and grilling meat. Usually the constable on the beat was standing in the kitchen, helmet in one hand, a mug of beer in the other.’ ‘The senior member – all clubs were required by the proctors to have a don responsible for them – was R.M. Dawkins, the much-loved professor of Modern Greek, who never, I think, set foot there.’ Another don, who did, was Sydney Gordon Roberts, known as ‘Camels and Telegraphs’. He was professor of Tamil and Telugu.

Harold Acton wrote in his memoirs:

A rugged set they appeared at first sight, and to me, exotic … but the ruggedness was an externality: it went no further than unshaven chins and beer-stained corduroys. Beneath a scowling facade most of them were sensitive and shy. Some were inclined to a communism which expressed itself in pub-crawls; others had hankerings after folk dancing and the Cowley Fathers [the first Anglican male religious order, founded in 1915 and based in the Oxford suburb]. Ale might loosen their tongues, but they preferred shove ha’penny and darts to conversation and were quite happy to shove ha’pence for hours, puffing at a clay pipe. At all hours I could find somebody there to talk to, somebody with a congenial hobby or mania.

But a change in the club’s character was under way. Harold Acton became a prominent member after he arrived in Oxford in October 1922. The next year his Eton schoolfriends, Robert Byron, Brian Howard, Hugh Lygon, Anthony Powell, David Talbot Rice and Henry Yorke, came up and joined. Alfred Duggan, another Etonian who was already there, first invited Powell to lunch at the club. Duggan, who came across to most as a proper English gent, was actually Irish-Argentinian. He was christened Alfredo. His extremely wealthy father had died of drink; ‘Alf’ was already an alcoholic. Powell recalled that he ‘was inclined to drink a pint of burgundy out of a tankard at lunch’. His American mother had married Lord Curzon, the former Viceroy of India. The fact that Curzon was chancellor of the university was often thought to explain Alfred’s continued presence there as a student.

As Powell recalled, the membership ‘was in process of changing from shove-halfpenny playing Bohemians to fancy-dress wearing aesthetes. One of the rowdiest members was Evelyn Waugh, one of the most sophisticated Harold Acton.’ Waugh wrote:

The difference between the two antagonistic parties may be expressed in parody by saying that the older members were disposed to an archaic turn of phrase, calling: ‘Drawer, a stoop of ale, prithee’, while the new members affected cockney, ordering: ‘Just a nip of dry London, for me wind, dearie’ … In its brief heyday it was the scene of uninhibited revelry … at the first, and only, general meeting which I attended, knowing scarcely anyone, I found myself, much to my surprise, proposed and elected secretary. The voters were all tipsy. I performed no secretarial duties. My appointment was a characteristic fantasy of the place, and after a time I had a tiff and either resigned or was deposed – I forget which.

On his first visit, Powell had been told that Waugh was, temporarily, banned ‘for having smashed up a good deal of the Club’s furniture with the heavy stick he always carried’.

With rare exceptions, sons of the lower-middle and labouring classes were not invited to the club. The future playwright Emlyn Williams, from a Welsh-speaking, working-class family, on a scholarship, remembered Harold Acton being pointed out to him in the street: ‘He’s the Oxford aesthete … and he belongs to the Hypocrites Club with Brian Howard and Robert Byron and Evelyn Waugh and all that set … They’re supposed to eat new-born babies cooked in wine.’

Waugh’s predecessor as secretary, Raoul Loveday, he wrote, ‘had left the university suddenly to study black magic. He died in mysterious circumstances at Cefalù in Aleister Crowley’s community.’ Loveday had become obsessed with Egyptology and the occult, and had fallen under the spell of the man John Bull magazine called ‘The King of Depravity’, ‘A Man We’d Like to Hang’ and ‘The Wickedest Man in the World’. In 1920, Crowley had set up a kind of cabbalistic commune in a farmhouse in northern Sicily, which he called the Abbey of Thelema. Waugh later included a portrait of him as the ludicrous Dr Kakophilos in his 1933 short story Out of Depth. Dr Trelawney in A Dance to the Music of Time is another character based on the magus. In Brideshead Revisited, Waugh writes of Anthony Blanche ‘practising black art in Cefalù’. This doesn’t seem to have been part of the resumé of either Howard or Acton.

In 1922, Loveday, along with his new wife, arrived in Sicily to become Crowley’s ‘magickal heir’. Anthony Powell, who later met Crowley in London, wrote:

The early forms of the Loveday myth had centred on a projected undergraduate expedition to rescue this Oxford friend from Crowley’s clutches. I think the party was to have included Alfred Duggan and several other members of The Hypocrites. By the time the story was retailed to me Loveday himself had died the previous year.

At first, all had gone well. Loveday had spent each day practising the Lesser Banishing Ritual and performing some of the functions of a High Priest. But then, early in his tenure, he went for a walk. Ignoring Crowley’s for once quite sensible advice not to drink from the local streams, he did so, caught a fatal dose of gastroenteritis and died within a few days. In a book later written by his wife, Betty May – and published by Powell – she claimed that her husband had fallen sick when Crowley had forced him to sacrifice a cat he believed to be possessed by an evil spirit, and drink its blood. Little wonder the Hypocrites acquired a sinister reputation. Crowley later attempted to recruit Tom Driberg as his magickal heir, with no success.

No record of membership fees has survived – if one was ever kept – but the club was run on a professional footing. Anthony Powell wrote:

The Hypocrites was staffed by a married couple called Hunt, with an additional retainer, Whitman. Mrs Hunt did the cooking (simple but excellent), her husband and Whitman acting as waiters. Hunt was clean-shaven, relatively spruce; Whitman, moustached, squat, far from spick and span … Both Hunt and Whitman were inclined to drink a good deal, but in their different ways, were the nearest I have ever come across to the ideal of the Jeevesian manservant, always willing, never out of temper, full of apt repartee and gnomic comment.

One evening Waugh had been served a drink just before closing time:

‘But, Whitman, I told you, when you asked, that I did not want another drink.’

‘I thought you were joking, sir.’

Song was a staple of the club’s entertainment. An enormously overweight undergraduate, Peter Ruffer, sang in a soprano and played the piano. Waugh described him as ‘the first of us to die, obese, musical, morose, often contemplating suicide in his rooms in the Turl, killed in the end by a quack doctor’. Christopher Hollis, another member, remembered ‘a very fat melancholic man who took up slimming and eventually slimmed himself to death’. Harold Acton wrote that Ruffer had told him that he liked to engage with ‘lonely hearts’ who advertised themselves in the classified sections of newspapers. He was once in correspondence with a man who claimed to experience a sexual attraction to hothouse plants.

Also at the piano was David Plunket Greene, an early enthusiast for American blues and West Indian calypsos. Despite being 6ft 7in, he was ‘prone to dressing up in debutantes’ dresses of scarlet chiffon’, according to Robert Byron. Through his friendship with Plunket Greene, Evelyn Waugh was later to gain entry to the world of the Bright Young People.

Robert Byron was another regular performer at the keyboard, accompanying himself singing Victorian songs in the manner of his heroine, Dame Clara Butt. Powell remembered him ‘contorting his features into fearful grimaces, while he sang Victorian ballads in an earsplitting alto’. He was also known for his uncanny impersonations of an elderly Queen Victoria.

Not all the members were exhibitionists. Graham Pollard – one of several Hypocrites to espouse communism – was already a successful antiquarian book dealer while still an undergraduate. Powell remembered him explaining that, ‘judging by the finger marks, he considered Love and Pain to be his scout’s favourite volume of Havelock Ellis’. A scout made one’s bed and skivvied. Later on, Pollard was instrumental in exposing the literary forgeries of Thomas J. Wise.

Powell also recalled the future eminent anthropologist E.E. Evans-Pritchard, ‘grave, withdrawn, somewhat exotic in dress’. In a photograph of the Hypocrites’ fancy-dress party that helped lead to its closure, Evans-Pritchard is robed in a flowing Arabian burnouse, in the manner of T.E. Lawrence. Later knighted, and a fellow at All Souls, he became known for his ground-breaking work on what was then called ‘primitive’ religion, witchcraft and magic, especially in East Africa. David Talbot Rice, who collaborated with his schoolfriend Robert Byron on two art history books, became a professor of fine arts at Edinburgh University at the age of 31.

But despite the reassuring presence of such academically able persons, the Hypocrites was too louche for undergraduates with an eye to their reputations. As telling as who was a member, or regular guest of the Hypocrites, are the people within the same wider social circle who were not. One refusenik was Cyril Connolly, whose professional and social life crossed again and again with those of the leading Hypocrites until his death in 1974. On an endpaper of a 1923 diary, he jotted down a list of what he called ‘bad-hats’ at Oxford. Along with Evelyn Waugh, they included Alfred Duggan and Harold Acton. In a second rogues’ gallery he listed Terence Greenidge, David Talbot Rice and Robert Byron. A.L. Rowse, a future don, was invited to breakfast at the club. He wrote of being led through ‘a tortuous staircase and along twisting passages to a room still filled with the atmosphere of beer, stale smoke and the nameless goings on of the night before: it quite came up to my expectations of wickedness. Not for me membership of such an establishment.’

A far more respectable institution was the Railway Club, founded by John Sutro, also a Hypocrite. The clubs’ membership overlapped – though the aristocrats of the Railway Club were members of that establishment alone. Their parents would have quailed if they had discovered their sons were Hypocrite habitués. Bryan Guinness, Michael Parsons and Henry Weymouth, and the young economics don Roy Harrod, would be lifelong friends of the group. Patrick Balfour, a member of both clubs, wrote that John Sutro’s:

was a conception typical of the Roaring ’Twenties. In what other age would a dozen young men put on full evening dress in order to travel on the Penzance–Aberdeen express from Oxford to Leicester and back on the Aberdeen–Penzance express from Leicester to Oxford, with no object but to dine on the way and drink and make speeches on the way back?

The Hypocrites’ disgraceful reputation carried far beyond the university. Every summer an aunt of Claud Cockburn’s gave a party in the garden of her house in Hampshire, to raise money for sick, aged or homeless cats. At the most recent one, she told him, a ‘nondescript, rather solemn undergraduate’, down for the long vacation, the guest of a local vicar, had begun to pontificate about the regrettable ‘tone’ of Oxford after the Great War. While most undergraduates were sober, hard-working and circumspect individuals, some others – ‘certain flamboyant and undesirable elements’ – thanks to ‘their vulgar capacity for self-advertisement’ and ‘meretricious display’, were giving the university a bad name.

The undergraduate named ‘that awful man Evelyn Waugh’ and ‘an equally frightful fellow called Harold Acton, who used to shout his own poems through a megaphone’, as well as Robert Byron and several others. ‘One heard’, said the nondescript young man, ‘really hair-raising, almost unbelievable stories of the goings-on at the club – called so appropriately the Hypocrites Club – which these elements seemed to have made their headquarters.’ Thankfully, he was able to report that the authorities had taken the appropriate actions and the club was now closed down. ‘Disgraceful scenes, he believed, had accompanied this suppression. The Club had given a funeral dinner at an hotel in Thame, and leading members had driven back to Oxford riotously in a glass hearse.’ He was perhaps unaware of what had been taking place in this vehicle before it left Thame.

Cockburn’s aunt had heard enough. ‘I don’t know who you are, and I don’t want to know. I do know that you are a nasty little tittle-tattler and a disgrace to your university. I happen to know that a number of the people you mention are not only people of distinguished talent and ability, but are also friends of my nephew, Mr Claud Cockburn.’

‘Heard of him,’ mumbled the young man miserably.

‘About all you’re likely to do.’

Cockburn was never able to discover how she had come by this intelligence.

2

SWEET CITY

For no one, in our long decline,

So dusty, spiteful and divided,

Had quite such pleasant friends as mine,

Or loved them half as much as I did.

Thus Belloc of his Oxford; so I of mine.

(Evelyn Waugh, A Little Learning, 1964)

Evelyn Waugh’s extremely strong personality, his long and successful career as a novelist and journalist, and his lifelong friendships – and enmity – with the other Hypocrites, many of whom appear in his fiction, make him central to their story. At Oxford he began as an outsider, his background very different from that of Sebastian Flyte in Brideshead Revisited, the chic and brittle world of Margot Metroland and that of most of the other Hypocrites. While not ashamed of it – he said in later life that his childhood was idyllic – he seems to have regarded his family as slightly embarrassing.

Cyril Connolly remembered that when they first met at Oxford he asked Waugh, ‘Why do you make so much noise?’

‘I shout because I am poor,’ he replied.

Waugh often overspent, was sometimes broke; but he was never poor. His father, Arthur, was a littérateur, and a successful one. At Oxford he had won the Newdigate Prize for poetry and had written a piece for the first issue of the notorious Yellow Book. He wrote several books, including an opportunistic and bestselling biography of Tennyson, shortly after the Poet Laureate’s death in 1892. The poet Edmund Gosse, author of Father and Son, was his cousin. Arthur combined his writing and reviewing with publishing, becoming the managing director of Chapman & Hall. ‘Chapman and Hall’ became Waugh’s nickname for his father – in letters he sometimes addressed him as ‘Dear Chapman’. At the time Arthur Waugh took over in 1902, the firm had been treading water, having made considerable sums of money as the publisher of Charles Dickens. Waugh’s task was to inject some much-needed energy and he did. He became personal friends with many authors.

Evelyn was born on 28 October 1903. From the outset, his father could do little right in his son’s eyes. When he heard Arthur’s key in the door, and his calling out for Catherine, ‘that was the end of my mother’s company for the evening’.

I have also been told that at the age of four or five I fell into an unholy passion with my father, who, after a long and fully indulged morning at Hampstead Heath Fair, sought to lead me home to luncheon. I rolled in the sandy path abusing him as: ‘You brute, you beast, you hideous ass’, a phrase which became part of our family language.

Something of what a friend jokingly called the ‘Wavian’ style was already on the way.

Waugh Sr was fond of amateur theatricals, dramatic monologues and charades, which Evelyn found highly embarrassing. As late as 1925 he wrote in his diary that ‘My father’s jollity seemed more than usually distressing’. (Evelyn’s children remembered that he himself was an enthusiastic and impressive performer in just such activities when he was the same age.) His dissatisfaction with his home life was compounded by the strong sense that his brother Alec, his senior by five years, was the apple of his father’s eye. For one homecoming from school, Arthur had a banner made that welcomed Alec as ‘The Son and Heir’. (In a short story, Winner Takes All, Waugh writes of a pair of brothers, the older of whom is ludicrously over-favoured, though by their mother.)

Waugh’s friends saw things differently. Dudley Carew, a schoolmate, later a novelist, stayed with the family in 1922, and wrote:

without exaggeration it is by far the nicest house I have ever stayed in or that I can imagine ever staying in. The whole atmosphere is simply splendid and there is a kind of naturalness which one would have thought almost impossible outside one’s own house. Then again both Mr and Mrs Waugh are incredibly nice and Alec although frightening is really very charming.

He compared Waugh Sr to the impossibly sunny-tempered Cheeryble twins in Nicholas Nickleby.

Arthur was saddened that he and Evelyn didn’t have the same warm relationship he had with Alec. Evelyn got on better with his rather undemonstrative mother, Catherine. Only after his father’s death did he profess regret for their disjointed relationship. Alec Waugh wrote:

In later life Evelyn may have given the impression of being heartless; he was often snobbish, he could be cruel. But basically he was gentle, warm and tender. He was very like his father, but his father’s own emotionalism put him on his guard. He must have often thought, ‘I could become like this. I mustn’t let myself become like this.’

Famously – and this information must have come from Evelyn himself – from the age of 15 he walked several hundred yards from his home, Underhill in Golders Green, recently designated with a newfangled postmark, NW11, so as to post his letters in the far posher Hampstead, so they would be stamped as coming from NW3. His cousin, Claud Cockburn, had been told by a relative that Waugh’s sensitivity about class came from his mother, who was conscious that as a Cockburn, from a distinguished Scottish family, she had ‘married down’ when she wed into the more stolid Waughs. Neither of her sons makes any allusion to this theory.

Waugh went as a day boy to Heath Mount, a private primary school in Hampstead. Here he started and edited a school magazine, The Cynic. He also developed his great talent for cruelty, the wellspring of his comic technique. One victim was Cecil Beaton. Waugh wrote that:

I remember him as a tender and very pretty little boy. The tears on his long eyelashes used to provoke the sadism of youth and my cronies and I tormented him on the excuse that he was reputed to enjoy his music lessons and to hold in sentimental regard the lady who taught him. I am sure he was innocent of these charges. Our persecution went no further than sticking pins into him.

He carried on sticking pins into him. As ‘Davy Lennox’, a talentless and pretentious photographer and designer, Beaton makes his first appearance in Decline and Fall and is glimpsed in later novels. As with other Waugh targets, they met socially on a fairly regular, and seemingly amicable, basis for the rest of their lives. If Waugh’s victims hoped to draw the poison from his fangs by being on good terms with him in person, they were mistaken.

In 1917, Alec Waugh caused his father much grief when he published a sensational novel, The Loom of Youth, written when he was 17. It alluded, in guarded terms, to the highly taboo subject of homosexuality at a public school. Only two years earlier Alec himself had been removed from Sherborne, Arthur’s own school, for this same activity. The immediate effect of The Loom of Youth was that Evelyn was now barred from Sherborne. His father had to look elsewhere. ‘With a minimum of deliberation his choice fell on Lancing which he had never seen and with which he had no associations.’ Lancing had been founded in 1870 in support of the Anglican Tractarian movement. In Decline and Fall, Waugh describes Paul Pennyfeather’s school as one ‘of ecclesiastical temper on the South Downs’.

A peculiar rule of Lancing was that in their first term ‘new men’ could only speak and be spoken to by their fellow debutants. Because Waugh joined the school in January, an unusual term in which to start, there was only him and one other boy. So they were more lonely and bewildered than were most new arrivals. And no one had told the Waughs that the Feast of the Ascension Day was a full school holiday at Lancing. After morning chapel all the boys went off together or were taken out for the day by their parents – except Waugh. He spent the holiday hungry, miserable and alone, and ‘for the first and last time for many years, wept’. When he had children himself, on Ascension Day Waugh asked them to pray for ‘desolate little boys’.

He remained a shy, sensitive child, but, gradually, as he gained in self-confidence, he came out of his shell and transformed into the abrasive, combative character of legend. Dudley Carew wrote in his memoir of the ‘acted ferocity, the bulging, incredulous eyes, the bark of a voice … these were assumed to amuse himself, and, if the person at whom this barrage was directed was amused rather than intimidated, then so much the better and Evelyn joined in the laughter and reverted to his natural self’. In general this was to be Waugh’s modus operandi where social contacts were concerned for the rest of his life. He tolerated the company only of people who amused or interested him – and could give as good as they got.

Waugh went to Lancing an Anglican, though not an especially devout one. A fellow altar server was Tom Driberg, the future ‘William Hickey’, already moving further and further towards the highest of High Church devotions. Around the age of 17, Waugh lost his faith. He was to find it again, with a passion, in Roman Catholicism.

At school he studied illustration and calligraphy, wrote for the school magazine, scripted a precocious and confident school play, and formed clubs he called the Dilettanti, the Corpse Club and the Bored Stiff Club. When he was 14 he contributed a short essay, ‘In Defence of Cubism’, to the periodical Drawing and Design. This may have been done to annoy his father, more hidebound in his artistic tastes. Waugh’s liking for Cubism, and especially Picasso, was in later life to go sharply into reverse.

He took his entrance exams to Oxford in the winter of 1921 and gained a history scholarship, worth £100 a year, at Hertford College. He tried to persuade his father to fund him to live in France for several months to learn the language, so he could then arrive in the more usual first term of entry, Michaelmas, in October. Impatient as he often was to get things done in a hurry, Arthur insisted he went up straight way. Again, Evelyn arrived at an odd time of the scholastic year, in January 1922. This was to have unfortunate consequences later on.

At first, Waugh ‘lived unobtrusively’. Like that of Paul Pennyfeather at ‘Scone’ in Decline and Fall, his start at Hertford was low key:

I was entirely happy in a subdued fashion during these first two terms, doing all that freshmen traditionally did, purchasing a cigarette box carved with the college arms and the popular printed panorama of the Towers and Spires of Oxford; learning to smoke a pipe; getting drunk for the first time; walking and bicycling about the surrounding villages; making an unremarkable maiden speech at the Union; doing enough work to satisfy the examiners in History Previous.

Waugh socialised with men from Lancing, at different colleges, and with fellow members of his own. ‘Public-spirited senior men in Hertford asked freshmen to tea, usually with the aim of enlisting them in philanthropic and evangelistic work among hop-pickers or at the Hertford mission in South London, or in the League of Nations’ Union. I did not find much in common with these.’ The serious-minded Arthur Potts in Decline and Fall is cut from the same cloth.

At the end of his first term he wrote to Dudley Carew, still at Lancing, that life at Oxford was ‘all that one dreams’. In truth, he was somewhat dissatisfied, suspecting that there was an Oxford he had not yet discovered. Then he fell in with another Hertford undergraduate, Terence Greenidge – an oddball and kleptomaniac who regularly pocketed trinkets from fellow undergraduates’ rooms, along with pieces of litter he picked up off the street. Together they founded the ‘Hertford Underworld’. Its main function was as a lunchtime drinking club. ‘Commons’ of beer, bread and cheese were held in Waugh’s rooms. These sessions were christened ‘Offal’, after a sermon preached at an Oxford Catholic church, St Aloysius (the name of Sebastian Flyte’s teddy bear). It included the statement: ‘All the world, St Paul says, is offal.’ Christopher Hollis, who heard the homily, said that ‘we adopted the name to distinguish us from our more respectable fellow undergraduates’.

The Hertford Underworld had by this time branched out. Hollis was at Balliol. Harold Acton, who went up to Christ Church in autumn 1922, also became an Offal regular, even though he hated beer. He would sit, mostly silently, sipping water. He seems to have had an unrequited crush on one of the other members. By this time Waugh had moved into a larger set of rooms on the ground floor. One night a parcel of hearties roamed around the quad, and one of them was sick though his open window. An identical incident is the start of Charles Ryder’s love affair with Sebastian in Brideshead Revisited.

It was Terence Greenidge who introduced Evelyn Waugh to the Hypocrites Club. He didn’t keep a diary at Oxford – or if he did he destroyed it – so it’s not known when he first set foot there. The best guess would be at some point during the summer term of 1922. Although he doesn’t mention the club to Tom Driberg in a letter he wrote then, clearly he had by now found the Oxford he’d been searching for: ‘Life here is very beautiful. Mayonnaise and punts and cider cup all day long. One loses all ambition to being an intellectual. I am reduced to writing light verse for The Isis and taking politics seriously.’ ‘At Oxford,’ he wrote in 1964, ‘I was reborn in full youth.’

Waugh first met Harold Acton at a meeting of the Newman Society to hear an address by the Roman Catholic writer, author of the ‘Father Brown’ series, G.K. Chesterton. Acton wrote years later of his friend that ‘I still see him as a prancing faun, thinly disguised by conventional apparel. His wide-apart eyes, always ready to be startled under raised eyebrows, the curved sensual lips, the hyacinthine locks of hair … So demure and yet so wild!’

Judging by his own reminiscences, it’s not difficult to see why Evelyn Waugh didn’t live within his means at Oxford. He drank most of the day, dressed as a dandy and spent money on expensive first editions – at one point he had to have a fire sale of his books while still at Hertford. Undergraduates had to pay a certain sum every term for ‘battels’ – eating in Hall – whether they did so or not. Lunches at the George Hotel – its regulars were known as the ‘Georgeoisie’ – and dinners at the Hypocrites were expensive, especially when you were in effect paying to eat twice.

Another Hypocrites favourite was an up-market former coaching inn, the Spread Eagle, in Thame. Taking advantage of the lax drink-drive laws of the day, parties of Hypocrites would regularly motor out the 14 miles from Oxford. The landlord, John Fothergill, though in his forties, was a kindred spirit. An undergraduate at St John’s, Oxford, he’d studied at the Slade and become a friend of Oscar Wilde, who gave him an inscribed copy of The Ballad of Reading Gaol.

Considered one of the first gentleman-amateur innkeepers, Fothergill was ferociously rude to any guests he took against, and would overcharge anyone he thought was ugly. The many excesses of the Hypocrites – he once described their dancing after dinner as akin to ‘wild goats and animals leaping in the air’ – did not faze him. Waugh presented him with a copy of Decline and Fall on publication, dedicating it to ‘John Fothergill, Oxford’s only civilizing influence’. The Spread Eagle is mentioned in Brideshead Revisited.

Consumption at these places was conspicuous. Patrick Balfour, later ‘Mr Gossip’ in the Daily Sketch, wrote:

Those were the days. The Hypocrites’ Club, where we drank as they never drank in pre-war Russia … There were other dinners: riotous dinners at the George, dinners given by Central European princelings on black tablecloths with seven different kinds of wine, dinners at the Spread Eagle at Thame, whistling through the night at 80 m.p.h. in a racing Vauxhall in order to be back by midnight.

The ease of living on credit at Oxford conspired to help undergraduates pile up debts. Peter Quennell said that ‘we were extremely lavish spenders; and, except for the very rich, we most of us went down leaving many bills unpaid’. Temptation was everywhere, as Quennell continues:

I had only, I discovered, to present myself at a shop, give my name and state my college; and the assistants would allow me to carry off any article that caught my fancy. At Adamson’s I could order new suits; at Blackwell’s, collect piles of volumes; even at the college-stores I was free to choose whatever provisions that I thought I needed – boxes of Russian and Balkan cigarettes, a magnum of champagne or some exotic liqueur such as ‘Danziger Goldwasser’, which I favoured not because I liked the taste, but because, if it were briskly shaken, delicate fragments of gold leaf floated to and fro inside the bottle.

Brian Howard wrote to Willie Acton, Harold’s brother, then still at school:

you have not heard from me lately … because these last three or four weeks have been so hysterical … about halfway through the term I let work – money – everything – just go. My God! I am miserable, though, as a result. I spent about £180 in two months – which, on an income of £450 a year, is idiotic. Last night – it is awful I can’t stop spending – I spent £5 simply taking a friend to dine at the Berkeley, theatre, and onto the Cabaret Club (which I loathe).

Rarely did buyer’s remorse last long. There was too much to see, to do, to spend money on. And there still was, when John Betjeman arrived in Oxford, in 1925:

I cut tutorials with wild excuse,

For life was luncheons, luncheons all the way –

And evenings dining with the Georgeoisie

(Summoned by Bells)

Waugh, for reasons he never quite understood, had chosen Representative Government as his ‘school’, or subject; increasingly, it bored him stiff. Not that another subject would have made a difference: ‘I regarded my scholarship as a reward for work done, not as the earnest of work to come.’ At first he seems to have been diligent enough in his studies. But soon there came a falling off.

Close readers of Evelyn Waugh’s novels and short stories will be familiar with the name Cruttwell. Beginning with the brutal safe cracker Toby Cruttwell in Decline and Fall, who castrates an abortionist, there are seven characters with the same surname, all of a ludicrous or demeaning nature. They include an unprepossessing guest in Black Mischief and a Conservative MP in Vile Bodies. There is General Cruttwell, a shop assistant with a false tan in Scoop, and a chiropractor called Cruttwell in A Handful of Dust. There is also a female avatar, Gladys Cruttwell, a ‘loyal and good-hearted girl’ who ends up as a booby prize for the main character in Winner Takes All.

The real C.R.M.F. Cruttwell, dean of Hertford and senior history tutor, was a distinguished scholar, a former fellow of All Souls. A wildly irascible man, he was scandalised by Waugh’s drinking habits and his dilatory approach to his studies, particularly since he felt that Waugh, as the history scholar of his year, had a duty to graft. Cruttwell later dismissed him as ‘a silly little suburban sod with an inferiority complex and no palate. Drinks Pernod after meals.’

In A Little Learning, Waugh wrote:

Cruttwell’s appearance was not prepossessing. He was tall, almost loutish, with the face of a petulant baby. He smoked a pipe which was usually attached to his blubber-lips by a thread of slime. As he removed the stem, waving it to emphasise his indistinct speech, this glittering connection extended until finally it broke leaving a dribble on his chin. When he spoke to me I found myself so distracted by the speculation of how far this line could be attenuated that I was often inattentive to his words.

Waugh put the boot in while he was an undergraduate, in a short story written for Cherwell, the student magazine edited by his friend John Sutro. A fictional counterpart of Waugh’s murders his hated history tutor, Curtis. The warden’s wife, distraught when she hears of the death, confesses to ‘the most monstrous and unsuspected transactions between herself and Mr. Curtis’.

At a lecture, Cruttwell, making some philosophical point, remarked, ‘Of course a dog can’t have rights.’ This was relayed to Greenidge. ‘It was Terence who first imaginatively imputed to Cruttwell sexual connection with dogs and purchased a stuffed one in a junk-shop in Walton Street, which we set in the quad as an allurement for him on his return from dining in All Souls. For the same reason we used rather often to bark under Cruttwell’s windows at night.’

Cruttwell’s rooms were directly above Waugh’s. Claud Cockburn remembered that one morning they were together:

drinking whisky against the enervating climate of Oxford, and listening to intrusive sounds of patter and thump from the rooms above. The rooms, Evelyn explained, were those of his enemy, the dean of the college whom Evelyn, as a blow in the feud, accused of having sexual relations with his dog.

‘Now he’s raping the poor brute. And at this hour in the morning.’

‘No hope,’ I said, ‘of it being just a faulty vacuum cleaner?’

‘No, no. You don’t know that man as I do. It’s him, no doubt of it. How I pity that unhappy dog.’

In 1935, Cruttwell stood in the Conservative interest in an election for one of the two university parliamentary seats, losing to the writer A.P. Herbert, much to Waugh’s satisfaction. The next year there was, finally, a sort of truce. Another short story, about a homicidal maniac, was originally published in a magazine as Mr Cruttwell’s Little Outing. When the story was collected in a book, though, ‘Cruttwell’ became ‘Loveday’. His biographer Christopher Sykes speculated that Waugh had heard that Cruttwell had recently suffered a complete mental breakdown, and decided to call off the dogs, real or imagined. Waugh himself wrote, in 1964, ‘He was, I now recognise, a wreck of the war in which he had served gallantly.’ According to Christopher Hollis, he had once remarked, ‘Really, Cruttwell is rather better than most of the Dons. But one must have someone to persecute.’

Cruttwell was not the only real-life Oxford contemporary to be mentioned by name in Waugh’s fiction. The vaguely sinister, protean Philbrick, the mysterious factotum in Decline and Fall, was named after an undergraduate who had been unwise enough to confide in Waugh that he had very much enjoyed caning small boys’ bottoms while he was a prefect at school. Waugh spread this information as widely as he could, so successfully that in a cinema one evening, when a scene of flogging unfolded on screen, the whole undergraduate audience as one began chanting, ‘Philbrick! Philbrick!’

In revenge, Philbrick and a friend waylaid Waugh and roughed him up. Philbrick’s accomplice in the attack was an undergraduate named Basil Murray – son of the famous professor of Greek at Oxford, and friend of George Bernard Shaw, Gilbert Murray. Later, Philbrick would give his name to characters in Waugh’s early short stories: ‘Miss Philbrick’, the secretary of an art school in The Balance, and ‘a menswear sales assistant’ in A House of Gentlefolks. Meanwhile Basil Murray, Waugh later wrote, provided one half of the recurring character ‘Basil Seal’. The other half was contributed by another undergraduate and renegade, Peter Rodd, later the husband of Waugh’s favourite confidante, Nancy Mitford. Both men were regular attendees, and most likely members of the Hypocrites Club.

For Waugh, revenge was a dish best served over and over again.

3

THE ETON SOCIETY OF ARTS

My Eton friends and I were voluptuaries of the imagination.

(Harold Acton, Memoirs of an Aesthete, 1970)

The majority of the Etonians who came to dominate the Hypocrites Club were members of the Eton Society of Arts, a debating club. Most of them also took voluntary art lessons at the school. The society included Harold Acton, Robert Byron, Brian Howard, Hugh Lygon, Anthony Powell, David Talbot Rice and Henry Yorke. This was a controversial group to join. To the more conventional pupils at the school, who were the majority, an interest in art was not really something you wanted to advertise.

Cyril Connolly, as he would later shun the Hypocrites, would have nothing to do with the Society of Arts, despite sharing the intellectual interests of its members. In Enemies of Promise he wrote that ‘they were the most vigorous group at Eton for they lived within their strength, yet my moral cowardice and academic outlook debarred me from making friends with them’. In particular, Connolly worried that close association with self-declared aesthetes would tarnish his reputation with the hearties, and scupper his chances of being elected to Pop, the much sought after self-elective society offering maximum prestige at the school. It worked; Connolly was elected.

The Society of Arts met once a week, and lasted for two years. Several members, including Howard and Yorke, were exposed to the arts through their parents’ interests. But none, then or later, could match the depth of cultural knowledge of one of the supreme aesthetes of his generation: Harold Acton.

He was born on 5 July 1904 in Florence, where his parents lived until their deaths. His mother was American; his father’s ancestors were Anglo-Italians who, from the eighteenth century, had been important functionaries, ambassadors and military leaders in the service of the Bourbons of Naples. The family lived at La Pietra, a beautiful villa outside the city with extensive gardens. It was full of priceless statuary, paintings, tapestries, furnishings and objects of virtù. Many of these had been chosen by Harold’s father, a connoisseur and collector. In his study Harold could leaf through books and catalogues of virtually every important artwork there was, and on his doorstep were the Uffizi and other galleries. The great art historian Bernard Berenson was a neighbour and friend.

In Memoirs of an Aesthete, published in 1948, Acton, perhaps drawing on his later immersion in Chinese philosophy, defines the spirit that guided his life:

I love beauty. For me beauty is the vital principle pervading the universe – glistening in stars, glowing in flowers, moving with clouds, flowing with water, permeating nature and mankind. By contemplating the myriad manifestations of this vital principle we expand into something greater than we were born. Art is the mirror that reflects these expansions, sometimes for a moment, sometimes for perpetuity.

His parents were friends with many of the leading artistic figures of the day. Before arriving at Eton, Harold had already met Gertrude Stein, Jean Cocteau, Gabriele D’Annunzio, Sergei Diaghilev, Léon Bakst, John Singer Sargent, Wilson Steer, Lytton Strachey, Norman Douglas, D.H. Lawrence, Rebecca West, Ronald Firbank, Edith Wharton and Max Beerbohm. In Brideshead Revisited, Waugh writes of Anthony Blanche, for whom Acton was one of the models, perhaps making sure to list only gay men: ‘he dined with Proust and Gide and was on closer terms with Cocteau and Diaghilev; Firbank sent him novels with fervent inscriptions.’

Like most of the Hypocrites, Acton was sent away to board at a prep school – in his case, Wixenford. Kenneth Clark and the Duggan brothers were fellow pupils. Like most prep-school boarders he was cold, damp, hungry and miserable. His talismans were not Boys’ Own stories, cream buns or editions of Wisden: ‘Among my private treasures I had a photograph of [Giovanni Boldini’s] portrait of Marchesa Casati with a greyhound, which acted as a wonderful antidote to an afternoon of cricket. Other potential antidotes, kept very secret, were a lump of amber and a phial of attar of roses’, the latter providing Proustian reveries of ‘Sorrento, Chinese nightingales and lacquered pavilions’. It helped that two more future Hypocrites were also at the school. During Sunday walks he ‘planned a magazine of art and fashion with Billy Clonmore, and a museum with Mark Ogilvie-Grant’.

At Eton, Harold Acton became close friends with Brian Howard. Both were obsessed by Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes. They hired a room at the back of a jewellers on Eton High Street and danced to gramophone records, taking the roles of Nijinsky and Massine. Howard was the most visible and voluble member of the Society of Arts. All through his life, he was a person very possible to dislike but impossible to ignore. Every one of his school contemporaries who wrote a memoir had something to say about him. Harold Acton wrote that ‘his big brown eyes with their long curved lashes were brazen with self assurance; already his personality seemed chiselled and polished, and his vocabulary was as ornate as his diction’. Anthony Powell – not an admirer – remembered that with ‘a dead white face, jet black wavy hair, full pouting lips, huge eyes that seemed by nature to have been heavily made-up, Howard had the air of a pierrot out of costume’. Henry Yorke thought:

he was quite the most handsome boy I’d ever seen – and remained so as a man up till the war … He was a brilliant conversationalist, even as a boy, and was able to dominate people by his conversation … He had tremendous charm – and could put it on when he wanted to.

But Yorke also called him ‘a terrible poseur and a wild snob’.

Brian Christian de Claiborne Howard was born on 13 March 1905. His father, Francis, known as ‘Tudie’, was an artist and critic, and an associate of Whistler’s. He organised exhibitions and became a very successful art dealer, managing the Grosvenor Gallery for Knoedler and Colnaghi. Brian’s mother, Lura Chess, was American, the daughter of a Confederate officer whose family had made a fortune in oil and then turned to manufacturing whiskey barrels. Her sister, Mary, invented a perfume in her own kitchen and founded a highly successful parfumerie. Lura later worked in the London shop.

Howard always believed himself to be partly Jewish. His father had changed his surname from Gassaway to Howard, for reasons never fully explained, but presumably to further his career as an art dealer to the English upper class. This change of name, and the possible Jewish ancestry behind it, was a source of fascination not just to Brian Howard himself, but to his peers too. Some of them would ask him, ‘And how is the Duke of Norfolk today?’, Howard being the family name of that branch of the aristocracy. Even in his late twenties he angrily wrote to his mother that his father had done him a disservice by ‘presenting me with an obviously false and pretentious name. Why didn’t he choose “Jones”? People might not have found out.’

Howard did not get along with his father, a womaniser who had fathered a child out of wedlock before Brian was born. Their relationship became increasingly toxic. As ‘Tudie’ became more emotionally distant, mother and son grew closer – too close. ‘Smothering’ was the word often used by contemporaries to describe their relationship. Freddy Birkenhead said of him, ‘I always thought Brian unfortunate in his parents. His father detested him, and his mother ruined him with her folly and indulgence. I remember the father describing with disgust how he had seen Brian at a party “smacking his great blubber lips.”’ By the time Brian was in his thirties he and his father were completely estranged.