Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

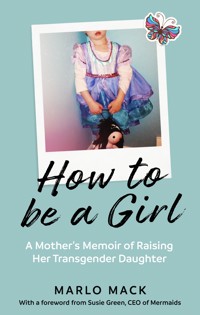

'ESSENTIAL READING' DIVA magazine ** Includes foreword from Susie Green, CEO of charity Mermaids ** Mama, something went wrong in your tummy. And it made me come out as a boy instead of a girl. Marlo Mack gave birth to M, a beautiful baby boy. Or so she believed. At two years old, M started insisting on wearing only pink clothes. At three, M begged his mum to buy him pretty dresses, and to grow his hair long. Friends, family, experts and Marlo herself had been able to brush these behaviours aside as a young child's playful experimentation with gender, but when her son begs to be put back in her tummy because he came out wrong, she knows she must listen more closely. How to Be a Girl is a raw and unflinching memoir of a mother grappling with her child's transition from male to female. Always wanting to support M, Marlo - whose podcast of the same name has over 1.3 million downloads - finds her liberal values surprisingly challenged, and as she learns more about gender and its varied expressions, she questions what being a girl - or a boy, or something else entirely - really means.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 282

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Acclaim for How to Be a Girl

“This beautifully written book is about parental love, pure and simple. And I don’t mean just the rhetorical ‘love’ claimed by all parents when things are going easy, but the unconditional ‘LOVE’ required when faced with something in your child that makes them—and you—potential pariahs. There is so much to learn here from Marlo and her gorgeous daughter M.”—CHRISTINE BURNS MBE, author and transgender activist

“This book is powerful because of its honesty and openness.”—FOX FISHER, artist, film-maker and campaigner

“I’m so grateful to Marlo and her daughter for sharing their story. Despite the obstacles all kinds of trans families face, resources like this make me feel lucky to be trans and to be a parent at this moment in time.”—FREDDY McCONNELL

“A stunning story…. Smart, honest, and deeply personal, this illuminating work should be required reading.”—PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

“How to Be a Girl exemplifies the true meaning of unconditional love. Marlo’s tender reflection and courageous love is an inspiration that will help others to their own awakening.”—JAZZ JENNINGS, author of I Am Jazz

“Marlo Mack’s How to Be a Girl is an extraordinary mother-daughter story and also a wondrously ordinary one, not just about a mother’s unconditional love but also about listening to one another, learning together, following your mama-gut as well as your mama-heart, and leaping into the unknown with a child—your child—as your guide.”—LAURIE FRANKEL, New York Times–bestselling author of This Is How It Always Is and One Two Three

For M., who hung the moon

CONTENTS

Foreword

When I was asked if I could write the foreword for Marlo’s book, How to be a Girl, I was both honoured and delighted, as I have a long history of following her work, much of which I have used in my work with Mermaids. Mermaids is a charity that supports transgender, non-binary and gender-diverse children, young people and their families. The charity has existed since 1995, but in the years since 2016, has changed and grown, as the need for our support services has increased exponentially.

My history with Mermaids began a few years after it came into existence, with a phone call in 1999 when my daughter, Jackie, was six. That seems so long ago now! I had searched on the internet for help, back when all connections were by modem, and I remember that hissing, clanging noise as it connected.

I typed in something like: “my son wants to be a girl”.

Since my daughter was four, for two years prior to that phone call, I had told her that it was OK to be a boy, but like girl things. I regret that time deeply. I didn’t listen to her clear expression and constant reiteration that she was a girl. Still aged four, she told me that God had made a mistake, and she should have been a girl.

At that point, I stopped ignoring her, and decided to stop denying her truth. I started to search everywhere for anything that would help me, which led me to my GP. I was told it was a phase.

Stuck, lost, isolated in a sea of people telling me not to encourage my child’s choices and preferences for girl’s things, I was almost paralysed by fear for her future. At six, she asked me when she could have the operation to make her a girl, having been told by an older cousin about gender-reassignment surgery. Faced with her complete misery when I said this was something that she could only do as an adult, I tried again to seek help with that internet search. Mermaids was in the list of options from that first search, so many years ago, and the only one with a phone number that I could see.

I called the number and spoke to a lovely lady, a founding member of Mermaids who manned the charity’s phone a few hours a day. I can’t remember much about the call, other than feeling a lifting of a huge weight. I think I cried several times, and felt held and understood for the first time ever. She didn’t judge my support for my daughter to express herself however she chose. She understood my need to find out more, and to try to protect my child. And her matter-of-fact explanation of her own trans daughter’s experiences made me feel less isolated and alone.

I joined Mermaids as a parent, and at that time there were around 25 of us in the group. I spoke to a mum whose child, at the beginning stages of puberty, became comfortable with their gender but was gay. I hung onto that hope that this would be Jackie’s future, as the public attitude to trans people at the time was horrific. Being gay seemed to me a much less imposing outcome. I also spoke to many more parents whose children found puberty agonising, as their bodies changed to reflect a gender that was not them. I found out about the Tavistock and Portman gender service for children, and went back to my GP to seek a referral for my daughter.

I was lucky, as the wait time was around six weeks, and I saw a local mental health specialist who had worked in the service and was happy to refer her. He was also the very first medical professional to tell me that I had not made this happen. The situation I found myself in wasn’t my fault. He also reiterated that it might resolve when my child hit puberty, but that kids like Jackie, who were very clear from a young age, were more likely to be trans. Only time would tell.

The diagnosis of gender dysphoria at seven years old was not a surprise, and the next few years were spent fighting a world that was not ready for trans kids. It was exhausting. Without Mermaids, I don’t know how I would have coped. I became more involved in the charity, became a trustee, and then eventually Chair. In the meantime, puberty began, and my already traumatised and victimised child faced changes that made her desperate to die. Cutting a very long story short, I tried everything to get her blocking medication to halt her puberty. In the UK at the time, nothing was available before the age of sixteen. I failed. Then, through dear friends at GIRES, another charity that supported transgender people, I found Dr Norman Spack. Norman is a paediatric endocrinologist, and he ran the gender services at Boston Children’s Hospital in the USA, and thus began our trans-Atlantic trips to secure medical intervention that I firmly believe saved my daughter’s life.

While all of this was going on, I was finding increasing representation of trans people as more information and personal stories began to appear online. I scoured the internet and any other resource I could find. Through this incessant searching, I found Marlo Mack.

This was in 2013, after years of volunteering with Mermaids, and as demand for the charity’s services were increasing.

The first video of Marlo’s that I watched was easy to understand, charming and colourful, and resonated so much with my own personal experiences. The shared anxiety, the tentative exploration of our children’s unique personalities and needs, the fears and the loss.

I was so grateful to feel that kinship, even across an ocean, and from that point forward, I included Marlo’s videos in presentations and training to other parents and professionals, and they were featured on the Mermaids website. The link to the podcast is still on our list of useful resources that we keep for the parents who are approaching us in their thousands. Our humanity, our struggles and triumphs, and unfortunately the hostility we face as parents who support their kids to be themselves is something that we share.

When Marlo contacted me late in 2020 to ask for help with another project she was taking part in, it was like being contacted by an idol. To be asked if I would write a foreword for this book was an easy decision to make. It was always going to be a yes. How could I say anything else, when her work, her openness and her honesty have helped so many other parents, including me.

Susie Green CEO of Mermaids

Author’s Note

The story I’m about to share with you is about real people. It’s about me and my daughter and those who have lived through this very interesting time with us. To preserve the privacy of my child and others, I’ve changed nearly all of the names, including my own.

What I have not changed is the story, as I actually lived it. I’ll be telling you this story from the beginning, which was ten long years ago, back in 2011. Back when I knew almost nothing about the profoundly complex and beautiful possibilities of gender; when I was the bewildered, doting mother of a precocious three-year-old who had so much to teach me.

Me: That’s a beautiful drawing.

My child (age three): Yes, it is.

Me: Can you tell me about it?

My child: It’s me and you, Mama.

Me: Which one is you?

My child: That’s me. You’re a princess. And I’m a fairy.

“A princess and a fairy,” drawn by my three-year-old.

STEP ONE

Take a deep breath.

There are not many moments like this. Moments that split open your world, slicing a deep crevasse across your life, so that everything before the moment belongs to a foreign, unvisitable world where a language is spoken that you no longer speak, and the words and customs of the new world are suddenly all that is comprehensible to you. It might happen after a big death, or the birth of your first child. Or it might be upon hearing a particular string of words uttered at that right, rare moment when your heart is raw and open.

That is what happened to me. I knew my child was different from the other children. I knew that most three-year-old boys did not spend long afternoons playing with plastic fairy figurines. I knew they didn’t beg their moms for ballet classes and princess dresses and everything that sparkled and glittered. I knew this was going to be more complicated, raising a boy who did not act like one.

The other moms assured me it would pass. At preschool pickup, they would enthusiastically compliment the surprisingly pink shoes worn by my little boy. “What a fun color!” a mom would say. And as my son smiled shyly and looked down to admire his beautiful feet, the mother of an older boy would tell me of the time when her own son had likewise mistaken the world of girls for his own. “My son loved pink in preschool, too!” she might say. Or “He used to dress up in his big sister’s clothes!” She would laugh at her sweet story, an example of the kind of charming error small children often make, like thinking you could draw your own money, or that your parents were old enough to remember the dinosaurs.

But I wondered.

I wondered if her son had ever drawn a self-portrait with puff-sleeved gowns and Rapunzel-length hair. Or recoiled at the sound of his own name, declaring it ugly and pleading to instead be called something pretty, like Rainbow. I wondered if her son had ripped off his clothes every day after school, to replace them with the floral-print party dress coaxed out of his grandma on a trip to the thrift store, and if he had then twirled around the living room in a graceful trance, singing a tuneless song about fairies.

I wondered if this mother had dithered and delayed in response to his ever-pinker requests, hoping this unusual passion would subside with time. If she had lain awake at night wondering where she had gone wrong, asking herself how she had so utterly failed to steer her precious boy in a safer direction, and whether there was any chance left of helping him change course now.

And I wondered how she felt when it dawned on her that all of the characters in her son’s favorite books, and the only children he requested for playdates, and every single one of his beloved stuffed animals … were girls.

Like me, she had probably never heard of a boy like that—a boy who didn’t seem to want to be one.

My child’s self-portrait, age four.

When the world split wide open, it was a November evening. We had just walked in the front door and were shedding the day’s damp coats and bags. Outside, the Seattle sky was preparing for an early bedtime, transforming the cloud ceiling from old-pillow gray to the color of wet ash.

I reached out to flip on the lights and felt my child slip his hand into mine.

“Mama,” he said, “something went wrong in your tummy.”

I heard my purse hit the floor. “It did?”

“Yes,” he said. “And it made me come out as a boy instead of a girl.”

The tips of his fingers dug into my palm, and I looked down at the three-year-old face tilted up at mine. The perfect brow was creased down the middle. His pale blue eyes, like circles cut from a summer sky, were flooding with tears, but did not blink. His little body, usually in constant motion, was unnaturally rigid and tall, a tiny soldier frozen at attention.

“Breathe,” I said to both of us. “Take a deep breath.”

He ignored me. “Put me back, Mama,” he rasped, expelling all that was left in his little lungs. “Put me back, so I can come out again as a girl.” He gasped for air and his body curled up into sobs. I sank to my knees and reached for him, but he pushed me away and pointed with his whole arm at my stomach. “Please, Mama!” my child howled. “Put me back!”

The evening’s last gray light was gone, the living room windows had turned black, and the door to the kitchen was now a bright rectangle filling the room with long shadows, including ours, which climbed the wall to the same height, and which were both trembling.

For months, I had been saying no to requests well within my power to grant: sundresses and ballet slippers and Barbie dolls. But now, my child was asking for something I couldn’t possibly deliver. Now, the only reasonable answer to give, unequivocally, was no. And I could not.

I could say no to all those pretty objects, but not to this. Because whatever this was, I knew that it was real, and it was everything. It was the thing he had been trying to tell me, and that I had been trying not to see, for months, despite 10,000 sparkly hints. It was impossible, but somehow it was also true.

I bundled him into my lap and heard myself promise my child something I had no confidence that I could ever deliver. “It’s OK,” I said. “You can be a girl.”

I held his damp head pressed against my heart and rocked him back and forth. He sniffed and shook in my arms while I continued to promise the impossible. “Yes, my darling. Yes.”

We were a single swaying shadow on the wall now, and we rocked and rocked, until his tears were dry and one of us felt safe again.

I NOW LIVED UNDER the daily weight of my impossible promise. Although I had been unable to say no, I also had no idea what saying yes actually meant. There was no way, that I could see, to actually keep my promise. A boy could not become a girl. I may as well have agreed to let him become a T. rex or a slice of toast.

The few friends I told got very quiet. They had never heard of a child saying such a thing, either.

When I told my mom what my child had said about returning to my tummy, she just sighed. Three grown children and nearly 70 years on the planet had not prepared her for a child like mine. “This is a new one to me, honey,” she said. “Have you told Will?”

I had not yet told Will, my child’s father. A few months earlier, our fifteen-year relationship had quietly crumbled, and our initially peaceful parting had devolved into a stereotypical brawl over the disentangling of two long-entwined lives. For the moment, our child spent most of the time with me and stayed at his dad’s new apartment a couple of nights each week. We were too angry at each other to discuss anything besides the basic logistics of co-parenting. So … no, I had not yet told my child’s father that our son wanted a do-over in my womb.

My child wanted to be a slice of toast, and I was all alone.

WHEN MY CHILD FIRST BEGAN venturing into the world of girls soon after he learned to walk and talk, his dad and I had pushed back—gently, we thought—cunningly employing various forms of the classic parental dodge: Maybe later. We’ll see. Those are too expensive.

When I caved and bought my child the bicycle helmet he badly wanted—a pale pink one, decorated with a family of bunnies—Will got annoyed. I could tell he thought I’d been weak, and I agreed with him.

I thought, surely those moms at preschool were right. Surely this was a cute and harmless phase, and soon enough he would wake up to the undeniable fact of his boyhood and start selecting from among the trappings of his true tribe: rough games played with balls, noisy toys that had wheels and gears, clothing in dark, muted colors. And besides, Will and I said to each other, we were just being practical: It simply wasn’t economical to invest in all the equipment of the wrong gender, only to replace it once our child woke up to who he actually was.

We did not say aloud the other things, the darker thoughts, that troubled us: If he kept going on this path, what would become of him? Who would accept him? Understand him? Love him? What would the world do to a boy like this?

If we could just coach him, coax him, into his boyness, perhaps we could save him from himself.

I scheduled playdates with little boys from preschool, though he never mentioned any of the boys—only the girls. I had to ask the teacher for the boys’ names and track down their parents. I looked into karate classes and tried to drum up enthusiasm by reminding him that his dad had once earned a black belt. I invited my sister to come over regularly with her two sons. They were slightly older than my child, and these few extra years imbued them with an older-kid glamour their younger cousin found irresistible. This cousin-worship gave me a slight hope. Perhaps he would begin to see himself in these boyish little gods and aspire to become like them. The three cousins would wrestle and roughhouse and sword fight with sticks, and when I watched them I felt a little easing around my heart.

But in the pile of writhing arms and legs on my living-room floor, the smallest pair of limbs were sheathed in shades of pink. And when the wrestling stopped, the youngest child went hunting for a princess dress and insisted it was time for a tea party.

Ultimately all our delays and dodges, our nudges and suggestions, failed completely. In spite of us, our child gradually amassed a wardrobe begged and borrowed from the girl world, the world with the things he loved. A lavender skirt fished out of a bag of hand-me-downs from a neighbor. A pink cardigan left behind by a visiting girl cousin. And the delightful spoils of his trips to the thrift store with Grandma, who didn’t see any good reason to say no to that two-dollar sundress, those sparkle-spattered T-shirts, that jeweled tiara.

“Oh, what’s the harm?” Grandma said. “When it gives him such joy?”

By the time his father moved out, just before the holidays and his fourth birthday, my child had purged his wardrobe of the last traces of boyhood and transformed himself into the pinkest child at preschool.

The moms who had once remarked so heartily on my boy’s unlikely pink shoes went quiet. Their own sons never took it this far.

Age three.

IT WAS JUST WARM ENOUGH to be outside. I was on hands and knees in the backyard, pulling winter’s weeds from a muddy flower bed. My child crouched nearby, perched like a bird atop hot-pink rubber rain boots, examining the pile of small, smooth stones he had spent the past hour collecting. I stopped weeding to watch as he picked up one of the stones, caressed it with his thumb, and put it back in the pile before choosing another that appeared identical. This one seemed to pass muster, and he laid it to the side in a weedless patch of dirt, then turned back to the pile to make another silent calculation. The chosen stones moved one by one until they formed a perfect circle, evenly spaced. Then he stood, hands on hips, and invited me to admire his work.

“Isn’t it beautiful, Mama?”

“Yes, it’s beautiful.”

A breeze tossed his wispy hair, the same almost-blond shade as mine. It was an unruly length, climbing over the tops of his ears and getting mixed up in his eyebrows because he had refused to let me cut it ever again, “now that I’m going to be a girl.”

Nodding at his circle of stones, he explained, “It is for the garden fairies. They do their magic here.”

I crawled in for a closer look. “Really? What magic?”

“Geesh, Mama!” He threw up his arms at my ignorance. “Fairy magic! Beauty and flowers!” He asked if we could go inside and make a fairy potion.

I hoisted him up onto the kitchen counter and poured some water and a little cooking oil into a bowl and handed him a spoon. He wondered aloud what colors mix to make purple and then remembered, then asked for help unscrewing the caps on the red and blue food coloring. Before I could stop him, he had squirted in half of each bottle. The spoon swirled the potion into a deep oily purple.

Back outside, he scooped purple teaspoonfuls from the bowl and bent down to pour precise magic over each small stone, making his way halfway around the circle. Then he stood and declared, “That’s enough,” and dumped the remainder in the circle’s center, creating a black puddle and splashing purple dots onto our boots.

I thought: He is four years old, and fairies are real. As real as the pale spring leaves unfurling on the maple tree branches arched over our heads and the damp grass under our boots. As real as the two of us, mother and child, bending over this circle of pebbles, splattered in purple magic.

“Now all the fairies will be happy,” he announced. “And they can have all their wishes.”

MY PARENTS CAME OVER to help with spring cleaning in the garden. While Dad mowed the lawn, Mom pulled weeds and admired the fairy circle, careful not to disturb it. She helped gather more stones for a second ring. My child proclaimed that it was now a fairy city.

That evening he directed the three adults into seated silence in the living room while he performed an elaborate and elegant dance, wrapped in a sheer lavender scarf and nothing else. We applauded heartily.

When we sat down for dinner, I complained about my job and told my parents that I was thinking of getting a roommate to help pay the bills.

Dad said, “You be careful about who you let move in here, with my daughter and my precious grandson!”

My child contemplated his plate of buttered noodles and said, “I wish I could drink a potion that would make my penis melt off.” Then he smiled, looking pleased with his great idea, like when he had suggested we build him a bed out of LEGOs.

The adults chewed in silence.

After dinner, Dad pulled me aside and asked if my child was spending enough time with his father. He was. Every week. And even though my interactions with my ex were brief and frosty, with his child Will was warm and attentive and playful. But I knew what people would think: His dad just left and now he wants to be a girl.

And I knew exactly how I would respond: My child has loved the world of girls since his first wordless encounters with it. Before he had names for it, he cried out for it, he crawled toward it. But of course, I too wondered and worried: Was my father right? Could these two events somehow be related?

It occurred to me that perhaps, and very probably, we were getting all stirred up over a misunderstanding. Surely this was really just a problem of definitions, of semantics, of the limitations of the available categories.

Me: What things are “girl things?”

My child (age four): Ballerinas, pink and purple, jewelry … and dancing on a stage.

Me: Can boys dance on a stage?

My child: Only if they’re getting married, like a prince.

I decided that we needed to expand the definition of boyhood, one that included what he loved. One that included him.

My own childhood took place in the androgynous 1970s. With my bowl-cut hairdo and brown corduroys, my gender was indistinguishable from that of my brother and every other little boy in the neighborhood. I remember being mistaken for a boy fairly often. But androgyny had gone far out of fashion by the time my child was born. In 2011, it was nearly impossible to glance at a young child’s clothing and guess their gender wrong. Unless, of course, you were looking at my son.

At playdates, all the moms complained about the resurgence in gendered toys and clothing, bemoaning the power wielded over their daughters by the Disney princesses, and rolling their eyes at their sons’ obsessions with guns and race cars. But no one seemed to be fighting back all that hard. Even my staunchest feminist friends marveled helplessly at the power of nature. “It’s just how it is,” they’d shrug. “They seem to be wired that way.”

I knew, of course, that there really wasn’t such a thing as a girl color, or toy, or career. I had taken women’s studies classes in college. I had a subscription to Ms. magazine. I knew that each generation’s unquestioned assumptions about gender roles would be mocked and tossed aside by the next. Perhaps one day my grandchildren would buy dresses for their little boys or return to the androgynous days of bowl-cuts and brown corduroys, but I didn’t have time to wait for social norms to evolve. I needed a world that would allow for a child like mine. Right now.

I decided to create one. I couldn’t change all the toy stores and clothing aisles. I couldn’t change the movies and TV ads. And I couldn’t change the language spoken by the rest of the world. But I could try to change the one we spoke. Inside our home, in our family, in our own little world, I decided, we would redefine gender—we would create a world in which boys could love pink and dream of princesses, and still be boys. We would expand the definition of “boy” to include my son.

I found a website selling pink T-shirts printed with the words BOYS CAN WEAR PINK, and I ordered one for my child, for his dad, and for his grandfathers. I sent the men an email explaining the important role they could play in defying society’s narrow definitions of manhood. I included a link to a Smithsonian magazine article that explained how pink had been a “boy color” up until the 1940s because it was considered strong and decisive, while blue, being a daintier color, was deemed best for girls. “Let’s reclaim pink for boys and men!” I wrote and asked them to consider wearing their new stereotype-smashing T-shirts when they spent time with my son.

A June 1918 article from the trade publication Earnshaw’s Infants’ Department said, “The generally accepted rule is pink for the boys, and blue for the girls. The reason is that pink, being a more decided and stronger color, is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl.”

—Smithsonian magazine,

April 7, 2011

I let my child sign up for the ballet classes he had been begging for and bought him a tutu and pale pink slippers over the objections of the horrified young woman at the dance supply store, who kept trying to tell me that “the boys’ slippers are black” until I interrupted her to explain that “my boy loves pink!”

I smiled conspiratorially at my son. “Isn’t that right, sweetie?” He smiled back and asked how many tutus I would buy for him.

At ballet class, all the other moms assumed he was a girl, and they admired my little ballerina’s unusually short haircut until I corrected them, too, with a friendly scold. “Surely boys can love ballet and pretty things?”

I went online to search for images of men and boys wearing the kinds of beautiful feminine clothing my child loved. There were lots of drag queens, but what I wanted to find were photos of people who just looked like … regular guys, but who also just happened to be wearing dresses and frills. You can find lots of people like this online these days—beautiful bearded boys in pencil skirts and sundresses. But this was back in 2012, when no one had yet heard of Caitlyn Jenner, let alone a bathroom bill. Donald Trump was still hosting The Apprentice, and mainstream gender expression was still relentlessly traditional. All my searches came up empty.

Ultimately, and absurdly, I found myself combing through websites on European art, looking for historic portraits from eras when powerful men had been allowed to wear gorgeous things: Renaissance dandies in striped tights and ruffled shirts, eighteenth-century aristocrats sporting long, curled wigs and silken slippers, toes pointed daintily as dancers.

I lined up a gallery of images on my laptop and called my child to my side. “Look at these pretty clothes these men are wearing!” I said, pulling him into my lap and pointing at the screen. “Those are MEN. In the past, all the men wanted to dress like this.”

My four-year-old looked at his mother like I had just said the cat was going to cook dinner. But I was desperate. Somehow, I had to remake the world in my child’s image. Somehow, I had to provide him an avenue to manhood.

“These are the kinds of pretty things you like, sweetheart!” I pointed at the golden tights of a powder-faced nobleman flanked by his pack of hunting dogs.

An image I showed my child.

He dutifully leaned in and squinted at the picture on the screen. “I like that little brown doggie,” he said, and wriggled off my lap.

One day another boy showed up in ballet class. I was thrilled. Unlike my boy, he was dressed like one, in gray sweats with white gym socks. Surrounded by diaphanous tutus and pink leotards, he looked like a dark bug in the middle of a bridal bouquet. And he looked miserable, sulking through the routines, phoning in his twirls, staring sullenly at the floor a few feet in front of him. I wondered why he had been forced to do something he so obviously hated. After class, I followed him to his mother. She was surprised when I told her there was another boy in the class. And then she looked down at my child and smiled grimly. “Oh. Caleb wants to wear that stuff, too, but we only let him do that at home.”

The two little dancers looked each other over, clearly confused. The one in gray pointed at the one in pink and turned to me. “That’s a boy?”

“Yes, Caleb, he’s a boy,” I said. “He’s a boy who loves ballet, like you.”

I expected my outgoing child to smile at his new friend, but instead he frowned and kicked the wall, crumpling the soft toe of his pale-pink slipper. It looked painful. His lower lip popped out. Caleb’s mom took his hand and pulled him away.

I hustled my own child out to our car, hoping he hadn’t noticed the look on the woman’s face. He was silent until we were buckled in. “It isn’t nice when you do that, Mama.” He glared at me in the rearview mirror.

“Do what?”

“When you tell people I’m a boy. It is not nice.”

“But you are a boy, sweetheart,” I said. It didn’t seem fair not to say what was true. “You’re a boy because you have a pen—”

“No,” he interrupted me. “I’m never a boy.”

I had no idea how to argue with this declaration. But I also wasn’t prepared to agree with it, so I opted for a compromise. “OK,” I said. “I’ll stop telling people you’re not a girl. Would that make you feel better?”

He snorted, rolling his eyes, as if to say, If that’s the best you can do, lady.

For now, it was.

HELPFUL (AND CONCERNED) FRIENDS and relatives suggested I read my son a popular new children’s book called My Princess Boy. It’s about a boy who loves princess stuff and whose family accepts him just as he is, dresses, sparkles, and all. I bought the book and ended up with several more copies of it, gifts from the same helpful and concerned friends and relatives. We read it exactly once. After the last page was turned, he slammed it shut and threw it across the room.

“I hate that book,” he said.

“Why? Why do you hate it?”

“You know why, Mama,” he said.

Me: