Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

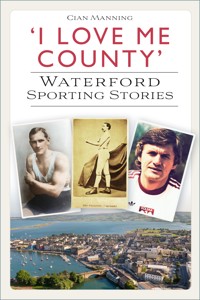

Waterford, the Gentle County, can boast a proud sporting tradition that is as long as it is unusual. Ireland's oldest city has witnessed many trends, from blood sports like bull-baiting in Ballybricken to roller hockey at the Olympia Ballroom. But the towns and villages of County Waterford were not to be overshadowed, producing notable sports people such as basketballers and boxers. In 'I Love Me County', learn about everyone from camogie pioneers to World Champions, as this collection of stories records the lives, loves and losses of some of Waterford's forgotten sporting heroes, demonstrating the importance of sport and leisure in the history of the county.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 440

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Cian Manning, 2024

The right of Cian Manning to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 803 99256 3

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

Contents

Introduction

1 ‘Savage Manners and Inhuman Barbarity’: Bull-Baiting at Ballybricken, 1714–1826

2 ‘The Hub of Hikers’: Waterford and Rambling, 1775–1930

3 Johnny Ryan (1826–1907): Portlaw’s Pre-Eminent Sportsman

4 Hugh Collender: Cappoquin Sports Manufacturer and Rebel

5 Patrick Hearne: ‘The Gambler’

6 The Irish Giant ‘Who Gained Notoriety, if Not Fame, as a Pugilist’: Lismore’s Ned O’Baldwin (1840–75)

7 Vere Thomas St Leger Goold (1853–1909): Waterford Tennis Player and Monte Carlo Murderer

8 ‘Died of Inanition’: County Waterford Archery Club, 1860–65

9 Thomas Joseph Dart Kelly: Waterford Man and Aussie Cricketer

10 Joe Tracy: America’s Greatest Race Car Driver

11 Waterford’s First Hurling Revival, 1884–1934

12 Patrick Street, Pugilism and Preaching: Stories of Arthur Clampett

13 Dungarvan was his Hometown: Shaw Desmond (Author and Spiritualist)

14 To the Waterford Coast and Along it: Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (1859–1930)

15 ‘The Palm of Superiority’: Handball in Waterford, 1887–1911

16 Heavyweight Boxing: Champion of the World Visits Waterford, December 1887

17 Jack Mitchell: ‘The Man with the Plate in his Head’

18 ‘Urbs Intacta was Supposed to be at Stake’: Oxford and the Waterford City Regatta, 15 July 1890

19 ‘A Cycling Carnival’: Ireland vs England, People’s Park, Waterford, 11 August 1891

20 T.O. Jameson: The Captain at Cappoquin

21 Dan Cooney (1892–1940): ‘Our Dan’ from Near Dungarvan

22 The Wild Man from Borneo: Grand National Winner 1895

23 ‘The First Waterford Men to Win All-Ireland Medals’: Jack Dwan and Larry Tobin, Tipperary Footballers

24 ‘Battling Brannigan’: The Story of Gerald Hurley

25 An American Millionaire at Waterford Harbour

26 ‘Aesthetic Appeal’: The Many Lives of Edward Augustine McGuire (1901–92)

27 ‘I Fail to See Why we Cannot Play Polo’: Waterford Polo Club, 1904–06

28 Patrick Joseph Mahon: Forgotten World No. 1 Golfer?

29 ‘Old Men and Novices’: Roller Hockey in Waterford, 1910–85

30 Danny Morgan: Cheltenham Gold Cup-Winning Jockey and Trainer

31 Camogie in County Waterford, 1913–17

32 Matt O’Mahoney: Kilkenny Soccer Pioneer

33 ‘Sleeping Draught’: Michael Lacey, the Forgotten Contender

34 Check Mate: Austin Bourke, Chess and the Irish Weather

35 Dungarvan’s Denis Kelleher: An ‘Unpredictable Irishman’

36 ‘“Non-Political” Bosh …’: Gaelic Games Abandoned at the Sportsfield, 21 October 1923

37 A Portrait of my Grandfather as a Young Man

38 Waterford Hockey Players Tour America, 1925

39 Waterford City: Munster Junior Cup Winners, 1928

40 A Tale of Two Millionaires: Donaghy and Capelli, 1937–38

41 Josie McNamara: Waterford’s ‘Queen of Sport’

42 ‘Ideally Suited to the Irish Temperament’: Waterford Fencing Club, 1948–73

43 Colonel James Flynn: Irish Olympic Basketballer

44 Waterford FC in Iceland, May–June 1953

45 Mutiny on a Boundary: The Blyth Affair, Waterford, 1954

46 Waterford and District Table Soccer League, 1957–60

47 Suirsiders, Sliotars and the Silver Screen: Hollywood and the 1957 All-Ireland Hurling Final

48 Sea Lions and Walruses: Baseball in Tramore and Waterford City, 1958–66

49 The Brown Bomber at the Arch in Tallow

50 Waterford Ladies’ Soccer League, 1967–70

51 ‘Sell A Dummy’: Louis Fulloné, Failed Waterford Trialist, and Diego Maradona

52 Poles Apart: Piotr Suski, Włodzimierz Lubański andthe League of Ireland

53 Celtic Squash Club: A ‘Great Waterford Nursery’

54 Alma Delahunty: Ruánmhór Rúnaí (1981–85)

55 Samba in the South-East: A Brazilian in the League of Ireland

56 Jason Phelan (BMX Rider): Déise Daredevil

57 Grace Doyle: ‘The Stoke and Love of Surfing’

58 Evan Power: The Future of Irish Polo

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Introduction

The motto for Waterford city is the Latin, Urbs Intacta Manet Waterfordia – literally translating as ‘Waterford remains the untaken city’. The County Waterford motto reads as Déisi oc Declán co Bráth, with the Old Irish corresponding in English as ‘May the Déise remain with Declan forever’. Both are reflective of the eras in which they were given. The Latin motto dates to the fifteenth century, bestowed by King Henry VII after Ireland’s oldest city repelled two pretenders to the English throne. The county motto is taken from a ninth-century text on the life of Saint Declan, who founded the renowned monastic settlement at Ardmore. It was adopted as the motto on the county coat of arms on 9 June 1997. They illustrate the differences that are often displayed and felt in the histories of the city and county.

However, both have been usurped in the modern local lexicon by the phrase ‘I love me county’. On 27 June 2004, Waterford defeated Cork in the Munster Senior Hurling Championship final for the first time since 1959. Prior to the game (which would subsequently be considered one of the greatest provincial finals of all time) the Rebel County had beaten Na Déise 8–3 in head-to-heads in the Munster decider. Although the neighbours had met in the 2003 final, the previous times they faced each other in the Munster showpiece (in 1982 and 1983), the Leesiders had run out winners on both occasions, by a combined total of 50 points. To conclude that these were chastening defeats fails to convey adequately the sheer devastation, which wasn’t just disappointment but later evolved into apathy that lasted nearly a decade.

The dawn of a new millennium had been ushered in with a stirring in Waterford hurling, but also a renewed confidence in the city and county itself. The impact of the Celtic Tiger had generated social and economic progress in an area that had been in continual stagnation since the 1950s. The recession of the 1980s cast a ‘greyness’ over Waterford, which witnessed the generational wave of emigration that decimated Irish society, both socially and spiritually. As the Celtic Tiger roared, the area known as Cuan-na-Greinne (Harbour of the Sun) saw a city and county emboldened by membership of the European Union, looking out into the world, with a sense of pride in its cultural heritage and economic lot. This would be reflected in the county’s hurling team, as they displayed the character and colour of its people.

The star of the Waterford side from the defeat in the 2003 Munster final was De La Salle’s John Mullane. His 3–1 couldn’t propel Waterford to victory, as they lost by 4 points. The following year witnessed a see-saw match, which appeared to be turned on its head by the sending off of Mullane for an off-the-ball incident. As he made his way to the sideline, head bowed in a mixture of disappointment and self-disgust, it looked like his county’s chances had evaporated. However, his teammates had other ideas, and despite being a player down, they won the game by a solitary point. Mount Sion’s Ken McGrath lifted the trophy, becoming the second Waterford man in the twenty-first century to captain the county to provincial success.

A day of iconic moments was encapsulated by Mullane’s post-match interview on the field. Heartbroken amidst the triumph, the man who would go on to win five All-Star Awards uttered the phrase ‘I love me county.’ It was unvarnished, raw and from the heart. The words came from a place of bittersweetness. It was a reflection of the depth of affection that many inhabitants of the Gentle County feel for the area. They weren’t prose or poetry from a playwright or patriot, it wasn’t an earth-shattering historical event like a revolution or plague, but the result of an impulse due to sporting endeavours. It came from an ordinary working man, who on the field with his caman was transformed into a warrior, a hero. Not only did the phrase encapsulate the people of Waterford, but it also demonstrated what sport does to people, and why it is so influential. To paraphrase Jürgen Klopp, sport is the most important of the least important things in life.

The reason why sport is so important in Waterford, city and county, from Tourin to Tramore, along the rivers Blackwater and Suir, be it quaint villages like Lismore to housing estates like Lisduggan, is because it represents community. Sport can form the background of social calendars, be it christenings, weddings or even funerals. It is evocative and emotive, can lead to tears of joy or despair. Though John Mullane never did win an All-Ireland medal that he so richly deserved, he left a legacy far greater. In those few minutes in Semple Stadium, surrounded by Waterford supporters, he held up a mirror to the people of the Gentle County, and showed them themselves. All of us can relate to ‘I love me county’, Mullane gave words to what many felt.

This collection of stories is not the entire history of Waterford sport. It hopes to provide a flavour of the social, cultural, political and economic history of an area and its people through leisure pursuits and competitive endeavours. It is to acknowledge some of those figures whose stature have faded in time. We cast an eye over several neglected stories of Waterford sportswomen who pioneered various sports, and would take great pride in the healthy state and promotion of women’s sports today. The aim is to cast a different light on sports and trends that were once popular, and played frequently, which are now probably stuttering in their existence, while also looking at a couple of neglected stories in popular sports. Often times, with the proximity of events, we can turn away from the past, and forget about those who came before us. This is a tapestry of Waterford sport, from the niche to the underappreciated. Like John Mullane, a lot of these figures had a strong connection to the city and county. Hopefully, their stories will convey as much.

These stories are not about untaken cities or saints, but about the people of Waterford, and what it means to love one’s county.

1

‘Savage Manners and Inhuman Barbarity’: Bull-Baiting at Ballybricken, 1714–1826

Bull-baiting, prize-fighting, and the cockpit were ‘pleasures’ then much patronised by the bucks as well as the lower orders of society. The great prevalence of bull-baiting in Ireland has been ascribed to the old-time close connection of the country with Spain, and the consequent adoption of many Spanish usages and sports, as also to the fact that the Midland counties formed one great bullock walk entirely given up to the grazing of cattle to be deported from Cork, Waterford or Dublin.

Ballybricken, outside Waterford, was a favourite resort for bullbaiters, and was surrounded by houses from which spectators looked on as at a Spanish bull-fight. The centre for bull-baiting in Dublin was in the Corn Market. But these brutal exhibitions very often gave rise to much riot and bloodshed, and in 1798 were prohibited by law, and the ‘sport’ discontinued.

Nora Tynan O’Mahony, Freeman’s Journal, Thursday, 6 February 1913

The custom of bull-baiting in Waterford, staged at Ballybricken, where the Bull Post serves as one of the area’s most recognisable landmarks, saw the old Waterford Corporation ‘Ordered that a bull rope be provided at charge of the city revenue’ in October 1714, at the start of the slaughtering season. In the preceding centuries, Spanish merchants trading wine and fruit regularly traversed the Suir estuary. So extensive was their business that many of these families settled in the port city. Over time, they introduced their customs and pastimes to Ireland’s oldest city. Ballybricken came to be recognised as the perfect arena for bull-baiting, one twentieth-century commentator noting that it was ‘then an open space outside the city walls, but now surrounded by well-built residential and business houses, and also the venue of an important monthly cattle fair’.

Ballybricken Gaol.

In addition to the rope provided by the city for bull-baiting, dogs were required and easily procured. These canines were specially trained by locals, with one contemporary account detailing how ‘to enhance and render perfect the sport, a peculiar breed of dogs was cherished, the purity of whose blood was marked by small stature, with enormous disproportionate heads and jaws, the upper short and snub, and the under projecting beyond it’. It appears that the two breeds popular for bull-baiting were the bulldog and the Staffordshire bull terrier.

The custom then, come slaughtering season, was that every bull intended for butchery in the city could be commandeered by the crowd and baited before being killed. The historian Jack O’Neill suggests that the ‘justification for the barbarism of bull baiting, it was claimed that the baiting caused the heart to pump the blood at a faster than normal rate and this, it was contended, tenderized the meat’. The days surrounding baiting were big business, as people bet on dogs in the action, drank, etc.

Another right claimed by bull-baiters was that upon the election of a mayor, the civic official had to supply a brand new rope. This rope was given to the ‘Grand Council of the Bull Ring’ and placed in the city jail, where it was kept by the head gaoler until needed. This ‘Grand Council’ was selected by the citizens, and the leader known as the ‘Mayor of the Ring’ was appointed by the High Constable of Waterford city. The position was one of the most envied in the area, surpassing the role of the Corporation’s official ‘butter taster’ or ‘nightwatchman’. The latter in the nineteenth century was given a grappling hook to aid their effort in helping individuals from the river.

One newly elected mayor refused to supply the rope, leading to a bull being driven into his hallway, while a mob prepared to ransack and loot his residence. The mayor quickly granted the rope before his house was destroyed. ‘Rambler’ wryly remarked in the Cork Examiner that, ‘One has often heard of a bull in a china shop, but never of a bull in a Mayoral chamber.’ Another mayor refused to grant a rope, leading to authorities quelling a riot in Waterford. The ‘Mayor of the Ring’ had to arrange bull-baits on two feast days each year: Michaelmas and New Year’s Day. These were great civic occasions with much pageantry, as the Lord Mayor and Waterford Council walked to the hill through St Patrick’s Gate in their robes, while the first citizen carried a staff with a copper bull figure on top.

Otherwise, Jack O’Neill suggests that the season for bull-baiting lasted from October to 1 April. On the occasions of the mayor’s attendance, up to ten animals could be baited in one day. Another custom on the day when the council attended was for newly wed brides to kiss the mayor as another of his duties was to guard bachelors and approve of their subsequent choice of partner. At the conclusion of the bait, the grooms were expected to entertain the mayor and council.

The exercise of bull-baiting saw a bull tied to a rope, about 2in in diameter with a leather collar and buckle, with the rope being passed through a ring in the ground. Once the bull was secured, the dogs were let loose, and the poor animal was baited until it was exhausted. Of the dogs, John P. Pender wrote (in 1929):

The savage ferocity and tenacity of these small animals was quite extraordinary. We are told that a single one, unsupported, would seize a fierce bull by the lip or nose, and pin to the ground the comparatively gigantic animal as if he had been fixed with a stake of iron. Even after the fracture of their limbs, the dogs never relaxed their hold, and it was often necessary at the conclusion of a day’s sport to cut off broken legs, and even in that mutilated state they were seen on three legs, running at the bull.

The citizens of Waterford formed a circle around the scene, while other spectators viewed from windows in nearby houses. Certainly in the seventeenth century, many of these dwellings had been built by Cromwellian settlers, transforming Ballybricken into a new suburb of the city. In the centre of the green, where the bull was tied, was a pole bearing a large copper bull on its top. This was removed near the end of the eighteenth century, replaced by a concrete structure mounted by a lamp. Referred to as the Bull Post, it would witness the speeches of Daniel O’Connell, Charles Stewart Parnell and John Redmond in the subsequent centuries. The steps of the Bull Post were to aid dogs in their attack on the animal. However, it appeared that this edifice was on the verge of being removed in 1929, with Pender noting that, ‘Now this again is threatened to be replaced by a ferro-concrete tower in connection with the Shannon Scheme. Progress!’

Fifty years later, Waterford Corporation approved the erection of a concrete statue of a bull to be placed on Ballybricken Hill, to symbolise the city’s association with the cattle trade in the nineteenth century, and as a traditional site of bull-baiting when the hill was considered ‘the Irishtown of Waterford’. It was hoped that the statue would be similar to monuments in Munich. This monument never came to pass. In December 1988, Jack O’Neill said of the Bull Post, ‘Nowadays, it’s a place where people gather to sit and chat in the summer sun, where old men speak of the days of the fairs and of days when this city was not an unemployment black spot. You can be at peace on Ballybricken Hill.’

An Act of George III in 1779 forbade the practice of bull-baiting, but was rarely enforced. After the 1798 Rebellion, the ‘sport’ was prohibited, although it continued to be staged in Waterford for another five years. However, the Waterford Mirror on 28 September 1808 reported:

The shameful practice of Bull-baiting has commenced in the city and neighbourhood, with all its usual symptoms of savage manners and inhuman barbarity. It may be useless to tell those who indulge themselves in this horrid amusement that it is utterly at variance with moral feelings and with the sacred obligations of religion.

In the pursuit of this immoral, irreligious and criminal sport, they violate the laws of society, and subject themselves to the full penalties of their transgressions. They trespass upon the property of their neighbours, and put the lives of their fellow citizens in the most hazardous jeopardy. Let them not imagine that they can do this with impunity.

We have only to add, that the Mayor and Recorder, with their unusual attention to the interests and peace of the city have resolved to punish every offender with the utmost severity, in order to secure the total suppression of a practice so injurious to morals, and so hostile to civilisation.

Irish politician and leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party John Redmond, c.1909. Michael Laffan noted of the Waterford City MP’s legacy that, ‘Nonetheless he was a worthy and noble representative of the Irish political tradition, he proved that patience, negotiation and compromise could bring about important reforms, he helped to embed parliamentary procedures in the habits and instincts of Irish nationalists, and he played a significant role in transforming Ireland in the decades before the First World War. The miscalculations and failures of his later years have obscured his many achievements.’

The effort to end the pastime was enhanced by a celebrated Quaker missionary visiting the city the same year. They formed a deputation to visit the Protestant bishop at his country seat at Dunmore East. Accompanied by Thomas Jacob and John Strangman, they made their way to Dunmore, where the lordship assured them he ‘would make a special effort to stop the practice, which was shortly afterwards discontinued’. Yet in 1826, bull-baiting was being revived in Ballybricken, with increased outrage over the now illegal sport being pursued on the Sabbath. Eventually, the practice died out and there were talks in 1884 to knock down the Bull Post. It was concluded by Alderman Smith that it was ‘a relic of barbarism and bull-baiting had now gone out of fashion’.

From a former Attorney General for Ireland, John Edward Walsh (whose father was from Waterford) we have a lively description of bull-baiting in Ballybricken. His memoir, Ireland Sixty Years Ago (published in 1847), details:

The south of Ireland, connected by several ties with Spain, adopted many Spanish usages and sports, among the rest, bull fighting, which degenerated into bull-baiting …

The place for baiting was an open space outside the city gate, called Ballybricken. It was surrounded with houses, from which spectators looked on, as at a Spanish bull fight. In the centre of the ring through which the rope was passed …

In 1798, when bull baits were prohibited, this apparatus was removed, and the sport discontinued; But prior to that it was followed with the greatest enthusiasm, and it was not unusual to see eighteen or twenty of these animals baited during the season.

Although the Bull Post remains, when reflecting on this practice of cruelty, it brings to mind the phrase of the past being a foreign country. As times change, and what is accepted as sport today can be completely different to prior decades, let alone centuries, it’s worth acknowledging what was considered entertainment all those years ago. It is better to recognise these troublesome aspects of our history, rather than ignore them. We do a disservice to the past and future generations if we don’t explore our history, even to the darkest recesses.

The Bull Post, Ballybricken, 1890s. John Edward Walsh detailed in his memoirs, ‘The place for baiting was an open space outside the city gate, called Ballybricken. It was surrounded with houses, from which spectators looked on, as at a Spanish bull fight. In the centre of the ring through which the rope was passed …’

2

‘The Hub of Hikers’: Waterford and Rambling, 1775–1930

As the pursuit of hiking became an increasingly popular pastime in the early 1930s, the Waterford News noted that ‘Waterford walkers in the past went on their travels with a less sense of its being “the thing.” They experienced, perhaps, more of the thrill of adventure.’ The same periodical believed that County Waterford could develop into a ‘hikers’ paradise’, such as a central point of Kilmacthomas, where ‘every road radiates towards fair region’. Furthermore, one could appreciate ‘the beauty of the mountains, the lure of the woodlands, the charm of waterscape (lake, sea and river) – all are at call’.

One author suggested that Melleray was selected as a monastic settlement for such reasons, ‘as the place for these pilgrimages of good pleasure and good health – health of soul and body’. Prior to the monks in Melleray, the summit of the Knockmealdown was the birthplace of Henry Eeles, who published numerous papers on electricity. He was known as Major Eeles, and worked as an agent to the Duke of Devonshire and watched over the erection of the bridge that spanned the River Blackwater in 1775. Additionally, in 1758, Eeles invented and exhibited his ‘flying coach’ at the grounds of Lismore Castle, which was later seen as a precursor to the glider. Retrospectively described as a primitive aeroplane, the ‘coach’ worked by a sail, with masts 11½ft high. The historian R.H. Ryland noted that Eeles’ work ‘appeared in the form of Letters from Lismore, and was printed in Dublin in 1771, he claimed credit of discovering the identity of electricity and lighting’.

The Waterford News believed that County Waterford could develop into a ‘hikers’ paradise’, such as a central point of Kilmacthomas, where ‘every road radiates towards fair region’.

Britannica notes that ‘Lismore, Irish Lios Mor, market town, County Waterford, Ireland. It lies in the Blackwater valley, at the southern foot of the Knockmealdown Mountains. A monastery was founded in Lismore by St Cartagh about 633. In the ninth and tenth centuries the Norsemen plundered it.’

Eeles’ final wish was to be buried on the highest part of the Knockmealdown (which stands at 2,609ft) with his horse and dog. At one time, Eeles was ‘disputed with Benjamin Franklin [for] the right to be hailed as the discoverer of the fact that lightning and electricity were identical’. Dr Grattan Flood questioned the location of the burial of Eeles. He wrote:

Ryland, the historian of Waterford, is more or less responsible for the legend. The real fact is that Henry Eeles, popularly known as Major Eeles, died at Lismore on October 7th, 1781, and by the terms of his will, was buried on the summit of Knockmealdown, so as to be nearer the home of his beloved lightning. He was the first to discover the identity of lightning with electricity, and his famous Letters from Lismore were communicated to the Royal Society, London, in 1755 and 1756 – his experiments, however, dating from 1745. One who had been present at the internment of Eeles in 1781 gave a graphic description of the burial, and he adds that the Major was not buried with his horse, dog, and gun, as chronicled on hearsay testimony by Ryland, for the simple reason that he had given up hunting in 1777, and at the time of his death had neither horse, dog, nor gun.

Portrait of Benjamin Franklin by Joseph Duplessis, 1778. At one time, Lismore’s Eeles was ‘disputed with Benjamin Franklin [for] the right to be hailed as the discoverer of the fact that lightning and electricity were identical’.

Some believed that Mackey’s book Porcelain was written as a guide to Waterford hikers, with the Waterford News commenting of the publication that it was the ‘first of the first in this hiking business’. During the author’s own journey, he was accompanied by an ass that drew a chariot for him.

There have been generations of Waterfordians who extolled the virtues and pleasures of walking; figures like Paddy Walsh, who would walk from the city to Dunhill and back, and Thomas Newenham Harvey, who believed that it was ‘an unwritten law that Waterfordmen must walk’ and detailed his marches in his diaries, which were later serialised by the Waterford News. Harvey lived at Cove Cottage, and became a member of Waterford Corporation in 1901. His business dealings included large printing works, which the Waterford Standard noted in November 1901 was ‘one of the leading firms of its kind in the south of Ireland, and finds not a little employment to-day both for male and female labour in the city’. Harvey was a much-respected stockbroker, and was only 65 years old when he died. He was buried at the Friends’ Burial Ground at Lower Newtown. Harvey’s legacy was assured when he left a substantial bequest, originally directed towards the freeing of the Waterford toll bridge, and if this wasn’t needed, that the funds would pass to the Corporation to be used for the extension of the free library, or towards establishing a technical school.

Others included John Ernest Grubb of Seskin, near Carrick-on-Suir, who was devoted to ‘hitting the road’; there was Mr Beckett, a member of the staff at Hearne & Co., who used to spend his weekends hiking to places such as Carrick; Ronayne Jennings and Johnny Walker, who would walk from ‘Elysium’ to Dungarvan. In his youth, Willie Fanning would make his way to Tory Hill at any opportunity, while Dr Storer, an organist at Waterford Cathedral, ‘rambled far and wide over the Waterford terrain’.

Furthermore, the burial places of General Blakeney and the electricity pioneer Eeles on different summits of the Comeragh and Knockmealdown Mountains illustrated the joy derived from hiking to such vantage points in the mountains and soaking in the views and tranquillity. James J. Healy wrote that Blakeney ‘was an eccentric being, who loved not man or woman either, and who after a period of some years in the gaieties of the world, and while still in the prime of life, constructed a dwelling on one of the hills, and with a single male attendant retired to live there in solitude’. He was later described by the Munster Express as the ‘Crusoe of the Comeraghs’.

The Waterford News from Friday, 12 June 1931 would conclude of hiking in County Waterford that:

One could go on indefinitely giving instances of walking as the chief inspiration of health and pleasure seekers in Urbs Intacta. There is no shadow of a doubt that Waterford could substantiate a claim to be the abiding place of pioneers in the latest development of athletics. One of our Dublin dailies has declared that hiking has ‘come to stay’ in Ireland. Waterford ought to stake its claim to being the hub of hikers.

However, not everyone was enamoured with this trendy hobby. Leesider in the Cork Examiner remarked:

It may be, as you say, a very healthy hobby, but it is to my mind being very much overdone. Clerks and typists who have to work all the week would do much better service to their health by having a good rest during the week-end instead of walking fifteen or twenty miles, which is far too much. The only advantage I can see in it is that it has made courtship a good deal easier on the man’s part. He hasn’t to be hiring cars and paying train fares and bus fares, as he had to do a few years ago before the craze began. What do you think of it?

Nearly two decades later, in February 1949 the An Óige organisation’s first outing for the season was a hike from Waterford to the Minaun at Cheekpoint. Thirty members set out at 1.30 p.m. and covered the distance at a brisk pace in two hours. The weather was so good that the group remarked that they could see the Saltee Islands from the top of the Minaun.

In the 1970s, a Comeragh Mountaineering Club was formed in Waterford for those interested in the mountains and all things concerning hillwalking, rambling, hiking, orienteering and the great outdoors. The club’s membership stood at sixty people, with nearly thirty participating in treks every Sunday. They would gather at the Hypermarket at 10.30 a.m. before starting their journey for the day.

Since the Covid-19 pandemic there has been an upsurge in people taking up hiking again, and perhaps when on their travels they can note the paths beaten by figures like Eeles and Blakeney before them. Even the Cork Examiner recognised that hiking was courtship, so could be the start of a totally different journey – romantically speaking.

3

Johnny Ryan (1826–1907): Portlaw’s Pre-Eminent Sportsman

On Wednesday, 30 October 1907, Portlaw bade a final farewell to Johnny Ryan. For over fifty years, Ryan served the family of the Marquess of Waterford, working for the third, fourth, fifth and sixth Marquesses before his death at the advanced age of 81 years old. The Waterford Standard noted that Ryan was ‘respected and beloved by all, but by none more genuinely than by the noble family whose predecessors he served as faithfully and well’. In addition to his connections with the de la Poer Beresford family, Ryan had at one time been a professional jockey, and had the distinction of one of the most impressive winning records in the history of horse racing, be it amateur or professional, on the flat or steeplechasing.

Ryan was born in Mountjoy Forest in Omagh, Co. Tyrone, in June 1826. His father was gardener to Sir Charles J. Gardner. At that time, Gardner kept a racing stable, and when Johnny was 11 years old, he hid under a barrow to avoid going to school. Ryan hoped to talk to Sir Charles to allow him to ride a horse. A deal was made that if young Johnny could ride a certain ‘wicked mare’ over hurdles, he would be allowed to visit the stables. This was achieved by Johnny, and it was the start of a seven-year apprenticeship to Sir Charles. From there, Ryan went to Captain Henrick of Johnstown, Co. Kildare, where he rode Black Dwarf. He competed at the Ballybar (Co. Carlow) races on the same animal and came to the attention of Lord Waterford. The horse was purchased by Waterford, and Ryan would say of that transaction that, ‘I believe [he] bought me too’. Ryan would remain at Curraghmore from 1834 until his death in the early years of the twentieth century.

Ryan’s prowess as a jockey found the perfect patrons in the form of the Curraghmore estate, for the 3rd Marquess, known as Henry Waterford, came fourth in the 1840 Grand National on his own horse, The Sea. Nearly thirty years later, in 1866, the National Hunt Steeplechase was run in Scotland for the first time. There at the Bogside meeting, the race was won by Lord Marcus Beresford aboard G. Ballard’s Burford. Marcus along with his brothers raced each other in a three-horse sweepstake run over the Williamstown Course as part of the annual steeplechase meeting at the Curraghmore Hunt. The three siblings rode in Beresford blue colours with distinctive caps. When Marcus finished riding in public, he was appointed starter to the Jockey Club. He resigned this position in 1890 to become the Master of the Horse to the future King Edward.

By 1844, Lord Waterford (Henry) had sixteen horses in training, which provided Johnny Ryan with ample time to train and practise. The Tyrone native was made second horseman, with the pack established at Curraghmore under the title of Lord Waterford’s Foxhounds. Ryan would carry the ‘Waterford blue’ during the racing season on horses such as Blue Skin, Redwing, Ballysax, Firefly, Lord George and The Sea, to name a few of the animals who would become celebrated across County Waterford. The writer Harry R. Sargent believed that Ryan’s record stood at 130 races rode for Lord Waterford, with no fewer than 112 victories. He finished second five times, and in third place on three occasions. This trio of bronze finishes all came at the Liverpool Grand National.

It was noted in Bailey’s Magazine (1904) that:

This extraordinary record was chiefly accomplished in Ireland, where there were many steeplechase fixtures during the forties and early fifties that have been long since abandoned; but many of his most brilliant victories were won in England, notably the Grand Autumn Free Handicap Steeplechase of four miles at Liverpool in 1849, which Johnny won on Sir John by two lengths from Vain Hope. The Doctor steered by Lord Strathmore, and Preceed, with Jem Mason in the saddle, were among the seventeen competitors in this great race.

Ryan and Sir John (carrying 11st 8lb) were the favourites for the 1850 Grand National, but were unlucky to place third in a field of thirty-two competitors. Even without claiming the ‘greatest race’, Johnny Ryan believed that Sir John was the best horse he ever rode over fences. His style of horsemanship was noted as ‘never flurried or excited, [Ryan] never lost a chance or took an ounce out of his horse unnecessarily, while his finish was most resolute and artistic’.

The autumn of the following year Ryan, with the mount of Lord George, won the Great Metropolitan Steeplechase at Epsom, the same year as winning the Epsom Hurdle Race. The death of Lord Waterford in 1859 was the end of Ryan’s career as a jockey. He then was tasked with looking after animals for hunting and hounds. The year before the lord’s demise, Ryan had swept the boards in Ireland, as they looked to finally win a Grand National, which the pair eagerly chased. An overview by Sargent in Thoughts Upon Sport on Ryan detailed:

He came from a racing stable at the Curragh, entered the service of Lord Waterford in 1842, and continued as first steeplechase and flat-race jockey, also as second horseman, until his lordship’s death in 1859. During these seventeen years Ryan distinguished himself on that flat and between flags in the ‘light blue and black cap’ to quite an unparalleled degree … Thus showing a record which I should say was never approached by any other jockey, professional or otherwise, in the annals of racing or steeplechasing.

His later years were in service as stud groom to Lord Waterford, where his horses were continually admired for their conditioning as hunts and hounds. Nevertheless, the man always known as Johnny in Portlaw would be affectionately known on the lands of Curraghmore as ‘the Jock’.

Curraghmore near Portlaw, County Waterford, is a historic house and estate and the seat of the Marquess of Waterford. The estate was part of the grant of land made to Sir Roger le Puher (la Poer) by Henry II in 1177 after the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland.

4

Hugh Collender: Cappoquin Sports Manufacturer and Rebel

Hugh Collender was born in Cappoquin, Co. Waterford, in December 1828. Hugh grew up in a small farm just outside the town. Collender was a fervent nationalist and was involved in an ill-fated attack on a police barracks, which led him to flee to America in 1849. While in the United States, Collender became an acquaintance of Kilkenny man Michael Phelan, who was considered the ‘father of billiards’ in America. Collender became Phelan’s protégé.

In 1853, Collender was Thomas Francis Meagher’s manager for his lecture tour of the southern states. Meagher became the godfather to Collender and Julia Phelan’s (daughter of Michael Phelan) first child. In 1855, Michael Phelan and Collender set up a joint venture named Phelan and Collender. They co-published The Rise and Progress of the Game of Billiards in 1860. Collender had a keen interest in chemistry and technology, which led him to develop the ‘combination cushion’ for billiards. The success of their business led them to donate much of their money to the cause of the Fenians.

In 1871, after Phelan’s death, the company was renamed the H.W. Collender Company. Two years later, Collender built a substantial factory in Connecticut for the manufacture of billiards tables. It would go on to employ 200 people, and subsequently become the market leader in billiards tables. The factory was destroyed and rebuilt after a fire in 1883, and a year later merged with a couple of other companies to become the Brunswick Bake Collender Company, with Collender as president. It has continued in existence since 1960 as the Brunswick Corporation. Collender died of kidney failure in New York in 1890.

H.W. Collender Catalogue (1879).

5

Patrick Hearne: ‘The Gambler’

Patrick Hearne was born in Waterford. One of four siblings, Patrick was the son of a solicitor. He and one of his brothers would follow in their father’s footsteps, practising law in North America. Hearne received a BA from Dublin University (more commonly referred to today as Trinity College Dublin). He travelled to Canada in the early 1830s, but limited opportunity for employment led him to venture south to New York.

Such is the spread of the Irish diaspora: by chance, Hearne met an old friend from Dublin while walking down Broadway on his first day in the Big Apple. From there, he travelled to New Orleans, which was termed the ‘El Dorado’ of the nineteenth-century USA. The journey itself was owed to the kindness of the ship’s captain, who allowed the Waterford man to travel without paying the fare on the basis it would be paid when financial circumstances could permit.

The southern city became the third most populous in the States, with substantial numbers of German and Irish immigrants such as Hearne inhabiting it. There he found employment at a local law firm and the tidy sum of $1,800 a year, but his services were then severed due to the illness of his employer. The chance to become an accountant for a local gambling house, though not deemed a respectable job, certainly alleviated his financial difficulties.

With increased prosperity, a strong reputation in the casinos of New Orleans and good connections within gambling circles, Hearne returned to New York, eventually residing at 187 Broadway in the latter half of the 1830s. This move was precipitated by the tightening of restrictions on illegal gambling within New Orleans. His premises in New York was patronised by senators, socialites and wealthy businessmen of the day. Bearing his name, this gambling house (one of the first casinos in the city) opposite the well-known Metropolitan Hotel took considerable sums each night. Some of Hearne’s most renowned frequenters included prize fighters such as Yankee Sullivan and the popular minstrel Dan Bryant. Hearne’s gambling house was popular for ‘skins games’ such as bowling.

One of his gambling operation’s notable debtors was John James (an uncle of the novelist Henry James), who owed over $2,000 to Hearne. A campaign against the Irishman would see the term ‘social vermin’ aligned to his name in the local papers. The only case to be taken for ‘faro’ in New York was against Hearne; however, he was fined $100 with no term of imprisonment given. One writer quibbled, ‘What is a fine of $100, to Pat Hearne? He wins at an average, ten times the amount every night.’ Hearne was represented by the lawyer Daniel Edgar Sickles, who was later acquitted of the murder of his wife’s lover on the grounds of ‘temporary insanity’, which was also the first instance of its use in legal defence in the United States. It appears Hearne’s own trial impacted his enterprise on Broadway, which closed in 1856.

Yet, his wealth saw him buy the mansion of John Jacob Astor (a multimillionaire whose wealth derived from the fur trade) before selling it to be developed into an opera house. Of course, now Broadway is synonymous with theatre.

Upon his death in 1859, his obituary in the New York Times noted:

Mr Hearne was in his private relations so much of a gentleman, was so generous in his charities and so genial and kindly in his nature as to almost make us desire to forget that his profession was one which neither the laws of God or society could regard without condemnation.

His charitable nature would see little left for his grieving wife and two adopted daughters. From his ‘respectable’ origins in Waterford to becoming a pioneer in the gambling industry in New York, Hearne became one of the most well-known sportsmen before the outbreak of the American Civil War, but is largely forgotten in his adopted home and his native Ireland.

6

The Irish Giant ‘Who Gained Notoriety, if Not Fame, as a Pugilist’: Lismore’s Ned O’Baldwin (1840–75)

Along the 169km River Blackwater is the small town of Lismore, founded by St Carthage, which is dwarfed by the imposing Gothic-styled Lismore Castle. Among the near 3,000 population of this historic town in the 1840s was a child who would go on to be described as the greatest bareknuckle boxer prior to the great John L. Sullivan, but would meet a bloody end in a saloon in New York. Such was his pugilistic ability, C.J. Gannon described the Waterford boxer as ‘the Primo Carnera of his day’. Quite the claim by Gannon as the ‘Ambling Alp’ Carnera, who was the same height as the Irishman, has the record of more fights won by knockout than any other Heavyweight Champion.

Ned O’Baldwin was born in Lismore, Co. Waterford, in 1840. From that small town, O’Baldwin would grow to 6ft 6½in and weigh 200lb, with such a physical presence leading to him being dubbed ‘The Irish Giant’. The Sporting Life wrote that O’Baldwin ‘was brought up in the “land of prates [sic]” at Waterford, where many of the natives are vegetarians, and it is more than probable that Edward O’Baldwin was of that “persuasion”.’

O’Baldwin moved to London to spar at Langham’s but was outboxed by many of his opponents, who knocked him all over the shop.

Captain Francis O’Neill in the Chicago Citizen was far more ruthless in his summation that Ned O’Baldwin ‘gained notoriety, if not fame as a pugilist. Although but little short of seven feet in height and well-proportioned, his performance in the prize ring fell far short of his pretensions.’

‘Just Like That…’: The Schooling of a Fighter by Tommy Cooper

By his early 20s, O’Baldwin had amassed a series of impressive performances in his early forays in the fistic arts, such as an admirable defeat to Andrew Marsden (1863) followed by a victory over George Iles (February 1866, for £50 a side). He would avenge his loss to Marsden by vanquishing him in a rematch in eleven rounds in the autumn of 1866. The change in fortunes was noted by The Sporting Life: ‘of three years ago … [O’Baldwin] was then only a mere tyro in the sparring school, but was also wanting in strength and stamina … [he] was a giant of the beanstalk kind – thin, easily shaken, and apt to break away at the slightest touch’. A large part of his progress was due to the tutelage of Tommy Cooper of Birmingham, with Sporting Life recording of the second duel with Marsden:

The result has proved Marsden to have been clearly overmatched, and O’Baldwin has come out of the fray with his reputation considerably enhanced as a dangerous man to tackle in the 24ft ring. Marsden used his great strength by lunging out tremendous blows on O’Baldwin’s body and head, and at the end of the third round a swinging right-hander on the back of the neck was of such a stunning nature as to make Ned stagger, and a dish of cold water was thrown over his head to bring him to. This rendered Ned’s ‘headpiece’ rather shaky, and it was not till the sixth round that he recovered his true form, and then he dabbed on Marsden’s face and dropped his right on the ribs without any effectual returns. He gained a knock-down blow with a right cross-counter, and it was all up with Marsden after that; Andrew was bleeding profusely from two wide gashes on the nose and upper lip, and he was nearly choked with the blood running into his mouth … O’Baldwin soon found out that he had nothing to do but bide his time and let out his left, and it was sure to land on the dial somewhere. Had not the ropes and stakes been pulled up, we are of opinion that Marsden could not have stood up more than ten minutes, and we must confirm the referee’s decision in favour of O’Baldwin.

Of this run of noteworthy bouts, the Cork Examiner was more forgiving and positive of the Lismore man’s earlier forays in the ring, and added an air of mystique by proclaiming:

He has risen, meteor-like, to the zenith of gladiatorial fame. We have no record of his enduring the chrysalis state of the pugilistic pot-boy, and so far as we are aware, his great spirit has never been trammelled in laborious and degrading industry. When first heard of he was already the feared of doughty chiefs – vanquisher of Chickens, the exterminator of Pets, a dreaded antagonist of Bantams.

Aside from inflicting suffering on the animal kingdom (perhaps that’s why he was a vegetarian), O’Baldwin had placed himself with the opportunity to become champion with a bout against Jem Mace, which was scheduled for Tuesday, 15 October 1867 in London. However, before even a punch was thrown, the fight was cancelled when the police arrested Mace when he was asleep in his bed in an attempt to clamp down on boxing and the vices that surrounded its staging.

The Irish Giant in America

This left the pair with the decision to leave for the United States to explore fighting opportunities there, as it was becoming increasingly difficult in England. However, O’Baldwin got on the wrong side of the law across the Atlantic, when he was committed to Tombs in New York for defaulting on a $1,000 bail in 1868. This was followed by a sentence of eighteen months’ hard labour at the House of Corrections, due to his involvement in an arranged fight with Joe Wormald at Lynnville, Massachusetts. His opponent escaped the same fate by absconding and giving ‘straw bail’. In one last attempt for O’Baldwin to salvage his petering pugilistic career, a fight was arranged between him and Mace again for 1872. O’Baldwin entered into a training regime in West Philadelphia, but was arrested and placed under a $5,000 bail not to leave Pennsylvania for the purpose of prize fighting. The New York Clipper suggested that this was ‘a put-up job’ by the backers of the ‘Irish Giant’, with their opinion being that ‘they were determined not to [let O’Baldwin] fight under any circumstances, as … [he] was not well, and they did not wish to lose their money’.

However, the truth appears to be that the Lismore man had a dispute with his backers when he received only $45 out of the $1,000 he was promised, leading him to strike a supporter named Mart Killacky. Some believed that if O’Baldwin had got his hands on a weapon, there would have been a fatality. Killacky owned a hotel in Atlantic City, New Jersey, where O’Baldwin stayed when preparing to fight Mace. Previously, Bell’s Life had reported that O’Baldwin had been ‘hard at work for some time past, and looks in prime order now’. Concluding of the whole episode, the Clipper decided that:

After all the expenditure and loss of time involved in the endeavour to bring about a consummation of the match between Jim Mace and Ned O’Baldwin within the orthodox enclosure, it has, as many have predicted would be the case, ended in a most unsatisfactory manner.

If anything, this summed up not only the repeated attempts of a championship fight between the pair, but was an apt way to look at the career of O’Baldwin, which after such great promise (after the second Marsden fight) was faltering.

Last-Chance Saloon: Slaying the Giant

Clearly, boxing wasn’t paying the County Waterford native, so he entered into a liquor store enterprise with Mike Finnell. It was located on West Street in New York in 1875. However, only a month into the endeavour, O’Baldwin was looking to call it quits as the business was not profitable, and to give one last attempt at making it in prize fighting in America. He had already started issuing challenges ‘to fight any man in the world’. This rather erratic behaviour enraged Finnell so much that on 27 September 1875 he entered the saloon and shot O’Baldwin twice. One bullet entered his abdomen and the second into his chest. O’Baldwin battled his wounds like he was in a prize fight, but eventually succumbed to his injuries two days later. Only in his mid-30s, O’Baldwin’s remains were buried at Holyhood Cemetery at Brookline, Massachusetts. Some in the New York press felt that O’Baldwin’s murder by Finnell had done a service to wider society, with the New York Herald claiming his demise may have been to the ‘public benefit’. Thus, with such sentiment, Finnell was found not guilty of ‘first-degree murder’, claiming he shot in self-defence.

Legacy

The Sporting Life believed that O’Baldwin’s untimely end ‘prevented the Irish giant’s true calibre from being ascertained’, while a Captain Francis O’Neill in the Chicago Citizen was far more ruthless in his summation of Ned O’Baldwin, ‘who gained notoriety, if not fame, as a pugilist. Although but little short of 7ft in height and well-proportioned, his performance in the prize ring fell far short of his pretensions.’ Some likened O’Baldwin to Jim Jefferies due to his size, but the Irishman was deemed slower compared to the Ohio-born ‘Boilermaker’, who won the World Heavyweight Championship in 1899 against Bob Fitzsimmons.

The story of Edward O’Baldwin from Lismore illustrates the connections between boxing and crime that have long existed in the world of prize fighting. The Irish Giant serves as an interesting fulcrum between the bareknuckle boxing world that made Dan Donnelly legendary and the Marquess of Queensbury-gloved fighting that we know today. O’Baldwin shows how improvements to one’s life can be made if the will and work ethic are there, but also that opportunities that are so sorely chased must be taken before a career dissipates. The Waterford fighter had the world at the feet of his 6ft 6½in frame in 1868, yet just seven years later this gargantuan fighter was six feet underground.