Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

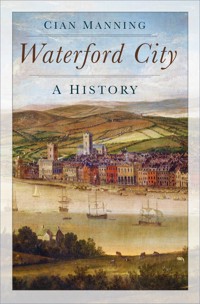

Founded by Vikings and later earning the nickname Parva Roma ('Little Rome') for its religious devotion, Ireland's oldest city has been witness to many significant historical events. From the marriage of Strongbow and Aoife to the splendour of the Georgian period, and from the first frog to be recorded in Ireland to the invention of the cream cracker, Waterford City: a History documents both momentous events and lesser-known stories. Discover the social and economic history of Waterford, and its notable characters who impacted the local, national and sometimes even the international scene.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 311

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Waterford City

CIAN MANNING

Waterford City

A HISTORY

Front cover illustration: Van der Hagen’s ‘View of Waterford’, 1736 (Waterford Treasures)

Back cover illustration: view of Waterford from the north-west, County Waterford c. 1890–1900 (Library of Congress)

First published 2019

The History Press97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,Gloucestershire, GL50 3QBwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Cian Manning, 2019

The right of Cian Manning to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9297 8

Typesetting and origination by The History PressPrinted and bound in Great Britain by TJ Internation Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction: Waterford, its Historians and Historiography

1 Vedrafjordr: Viking Waterford

2 A Royal City: Anglo-Norman Waterford

3 Urbs Intacta Manet Waterfordia: Late Medieval Waterford

4 Parva Roma – Little Rome: Waterford in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries

5 The Crystal City: Eighteenth-Century Waterford

6 Waterford in the Long Nineteenth Century

7 From Here to Modernity: Twentieth-Century Waterford

Epilogue

Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Over the course of researching and writing Waterford City: A History for The History Press, I’ve been fortunate to have met many erudite, obliging, encouraging and kind people. I would like to begin by thanking Nicola Guy of The History Press for all her help throughout the process of putting this book together and for being beyond generous in her support and advice.

A great deal of thanks goes to the Waterford Archaeological and Historical Society from whom this opportunity arose, with special thanks to Beatrice Payet, Ann Cusack, Erica Fay, Tony Gunning, Michael Maher, Donnchadh Ó Ceallachain and Clare Walsh for all their words of encouragement and for their willingness to listen and give a young person a chance to express their viewpoint. The society is a fantastic community of people who have a great love for history and that of the city of Waterford; it is one of the unsung organisations in our city and county that continues to go from strength to strength.

Thanks to Willie Fraher and all of Waterford County Museum for their help in relation to images. My gratitude to Joanne Rothwell of the Waterford City and County Archives for her help, advice and pointers throughout the process of putting this publication together. This can be clearly seen in the wonderful maps which illustrate this study. My appreciation also to Waterford Treasures, to its director Eamonn McEneaney, with particular reference to Donnchadh Ó Ceallachain (yes, the same person as named with the Waterford Archaeological and Historical Society) for all their help and pointers. Donnchadh is without doubt the most unsung person in the pursuit and promotion of the history of Waterford. He has always been kind to give his time and knowledge when approached about any aspect of history. Donnchadh may not have been born or bred in Waterford but it is a privilege that our city can count him among one of its champions.

A word of thanks to my friends Tracey Bradfield, Barry Condon, Daniel Collins, Tomas de Paor, Bart Gozdur, Gavin King (and his car Betsy for our frequent journeys across the island and the necessary break from writing), Maria-Assunta Lawton, Aisling McDonald, Ann-Marie Keating, David Robson, Rina Ryan, Joanne Tuohy and Eoin Walsh. I am honoured to call them my friends and can only be indebted to them for putting up with my antics. Particular thanks to Gavin, Tomas and Eoin who frequently listened to me discuss my progress with this book.

A great deal of gratitude to Peigí Devlin for all her time, help and expertise with the process of writing this book. Always generous with her time and opinions, this study would not have come to completion without her help and encouragement. It is a better work because of her input, and that is greatly appreciated.

Thanks also are due to Laura O’Brien and Mount Sion Primary School where, over the course of writing this book, I was able to present some of my research to several 5th classes. It was with great pride that I could return to my old school and meet some articulate and mannerly young men. It is safe to say with the pupils of Mount Sion’s love of the history of the city that the future of the city is safe in their hands.

Special mention for Grace and Dara Cunningham, Ben Penkert and Leia Murphy, Noah, Arwyn and Hugo Farrell and Lily Guidera for their part on the journey in writing this book.

I would like to thank my aunts Bennie Flynn and Elizabeth Foskin as well as my uncles Liam and Raymond Murphy for all their help over the years.

Thanks to my parents Oliver and Miriam Manning for their continued support and encouragement in all my endeavours. My interest in history and love of Waterford comes from both of them. My effort is always to try and measure up to the Manning motto of ‘to be rather than seem to be’, and teaching me to be myself has been the greatest lesson, one which I’m still learning with their help.

Thanks to my brother Olin who has always been a great sounding board for ideas and projects. Always one to express an opinion about what is interesting or isn’t, a lot of this book was written with him in mind.

INTRODUCTION:Waterford, its Historians and Historiography

I have given up doubt,That old, worn out coat.All that’s constantIs the fact of change;Pearl of love, grit of pain.

Sean Dunne, ‘Letter to Lisbon’,Time and the Island (1996)

The year 1746 is the foundation stone in the history of writing the story of Waterford. A Dungarvan doctor, Charles Smith, was the pioneer in recording the narrative of Waterford to that point and set a template which others have continued to follow to this day. Smith was a forerunner of Irish topography and local history. His collaboration with Walter Harris and Hans Sloane on The Antient and Present State of the County of Down preceded his work on Waterford by two years as the first in-depth history of an Irish county. This was followed by similar works on Cork and Kerry for the Physico-Historical Society, Dublin, which were advertised to wealthy individuals of the upper classes interested in improving their knowledge of Irish history.

Prior to the twentieth century, there were four histories of the county, three by men from Dungarvan (Smith in 1746, Ryland in 1824 and Hansard in 1870) while the quartet is completed by P.M. Egan (1894) of Kilkenny. Thus, with this in mind, The History Press Ireland has sought a history devoted specifically to the City of Waterford. In addition, it is worth keeping in view the characteristics and skills of these authors. Julian Walton writes that Ryland ‘certainly had his limitations; he lacked Smith’s painstaking if pedantic scholarship and Egan’s exuberant accumulation of detail’. It just demonstrates the difficult task to write a detailed, authoritative history.

Variation in approach can be seen with M.J. Hurley’s Links and Landmarks being a Calendar for the year 1900, recording curious and remarkable events in the History of Waterford City from the earliest times to the present day, which sought to cover anniversaries of historical events over the course of a calendar year, and which was published in 1900.

In 1914, Edmund Downey published his history of the city (re-published in 1932) followed by a work on the county by Canon Power in 1932 (re-published in 1937 and 1952). Downey is best described as a ‘Man of Letters’ since he was editor of London’s Tinsley’s magazine, then started his own publishing company printing Irish classics and his own works under the pseudonym ‘F.M. Allen’. His Illustrated guide to Waterford provided interesting biographical entries of accomplished (and not so acclaimed but noteworthy) inhabitants of the city.

View of Waterford from the north-west, County Waterford, Ireland, c. 1890–1900. Library of Congress

The latter man, Canon Power, of all the individuals outlined has probably left the greatest lasting impact. At University College Cork, Power held the Chair of Archaeology for nearly twenty years (1915–32). He was ordained in 1885 and began his parish work in Liverpool and subsequently New South Wales, Australia. Power returned to his hometown of Waterford, which coincided with the foundation of the Waterford and South-East Ireland Archaeological Society in 1894. He was a prolific writer, with his impressive recording of the place names of Waterford and around thirty other works from pamphlets to books. His 1907 Placenames of the Decies has been well thumbed by local historians and referred to continually by studies on Waterford, it has served as a template to anyone who would undertake such a momentous task.

Another marvel of his work is the Canon Power Memorial Map of County Waterford and Environs produced in 1953 by the County Waterford National Monuments Advisory Committee, which he chaired from 1931. Canon Power was described by Lawrence William White and Aideen Foley as ‘gentle and unworldly, with an old-word courtesy, Power was tirelessly devoted to his research’. The tradition that began upon Power’s return to Waterford with the Journal of the Waterford and South-East Archaeological Society continues to this day with its successor of the Waterford Archaeological and Historical Society’s Decies.

Another very important marker in the historiography of Waterford was the publication of Waterford: History and Society in 1992 under the stewardship of Des Cowman, Dr William Nolan and Dr Thomas Power as part of the county-by-county history series undertaken by University College Dublin. This interdisciplinary approach covered various facets of history encompassing archaeology and folklore to arrive at a broader understanding of the county’s experience through the centuries.

Two years prior to Waterford: History and Society was the publication of Patrick C. Power’s History of Waterford City and County in 1990. Significant works to have been published in more recent times include The Royal Charters of Waterford by Julian Walton in 1992 and Waterford Treasures by Eamonn McEneaney in 2004.

The level of recording the history in words is reflected equally in the process of preserving and displaying precious artefacts that illustrate the rich history of Waterford, while bringing to life the story and development of the city we live in today. In 1835, Thomas Wyse, MP For Waterford, sought for the government of the day to support the construction of a building ‘for the ordinary objects of an institute, a museum and a gallery of design’ at a meeting in the Assembly Rooms, City Hall.

In 1897, the Waterford and South-East Archaeological Society started a small museum in the city at the free library at No. 1 Adelphi Terrace (where the Tower Hotel is now situated) like that of the Science and Art Museum in Dublin where visitors could ‘inspect a collection of objects equal to any in Ireland’, as recorded in the group’s annual reports. By the early twentieth century, the museum moved to Lady Lane before settling at Reginald’s Tower in 1954 after the interior of the tower was modified to become a museum. At this time the collection was larger, with additions from Canon Power and the municipal collection to draw upon.

The archaeological excavations of the late 1980s and early ’90s in the development of the City Square Shopping Centre saw many of the artefacts found displayed in Reginald’s Tower. These items were transferred to the Methodist Church at Greyfriars Street, which was acquired by the council in 1988 to be refashioned as a museum to display the significant findings of the excavations in Waterford City (until 1999).

The 1990s saw conservation work on Reginald’s Tower (work starting in 1993) and the conversion of the Granary building on Hanover Street into a museum beginning in 1997. This led to the opening of Waterford Museum of Treasures in 1999, with the director of the museum, Eamonn McEneaney, outlining that ‘central to our philosophy in developing the exhibition was that the collection be accessible and welcoming to the public … On an intellectual level every effort had been made to appeal to as broad an audience as possible.’

Further development has seen Waterford Treasures move from Hanover Street to the Viking Triangle area in the creation of Ireland’s first museum quarter. Reginald’s Tower serves to showcase the history of Viking Waterford, the Bishop’s Palace has been converted into a museum displaying the history of the Georgian period to more modern times (opened in 2011), and the Medieval Museum, Ireland’s only purpose-built museum dedicated to the Middle Ages, was opened to the public in 2012. As our historical understanding continues to grow it is continually being matched by our thirst for knowledge, which is mirrored in the developments of these award-winning museums that cater proudly and boldly for all ages.

Now into the eleventh century of Waterford City, books published on the city’s history are more numerous, more colourfully illustrated and increasingly beginning to deal with a wider range of subjects compared to the staid ‘great men’ of history ethos. Such studies include Emmet O’Connor’s A Labour history of Waterford (1989) to more personal and anecdotal histories such as Ballybricken and Thereabouts, Waterford and Thereabouts and Reminiscences of Waterford which all appeared in the last decade of the twentieth century, they are thoroughly enlightening and highly engaging histories.

Medieval Museum in Waterford is Ireland’s first purpose-built museum dedicated to the Middle Ages. The gable end depicts an image from a belt mount dating to 1250. It may be a representation of Saint Margaret holding the head of a dragon which she has slain. Courtesy of Waterford Treasures

Works such as Julian Walton’s publicly adored On This Day radio slot (with selected episodes published to mark the 1,100th Anniversary of the establishment of the city in 2014) to Colm Long’s Random Waterford History (published in 2013) evoke much of our present tastes while allude to our historical forebearers such as Hurley’s calendar of 1900.

As Julian Walton, an eminent local historian, notes:

The local historian might keep these in mind. All great events have a local beginning or a local dimension. What happened locally may have been the seeds or the mirrors of revolutions, the fall of dynasties, or a cultural renaissance.

In the words of Waterford poet Sean Dunne, ‘All’s that constant / Is the fact of change’, which is reflected in the studies on the city. It can be explored in the make-up of those who wrote such histories being exclusively men with the strong presence of religion, such as in the careers of Reverend Ryland and Canon Power influencing their subject matter. If ever the writing of history is symptomatic of the times in which it is written, it can be seen in the historiography of the city of Waterford.

In twenty-first-century Waterford, the city is more than adequately catered for with academic historians, modern museums and an ease of access to information that has never previously existed. The Internet, with online platforms or social media groups such as the Waterford History Group, has allowed history to become an increasingly engaging and reachable subject for ordinary members of the public. There are various oral history projects that have documented childhood in Barrack Street, adolescent experiences in the Savoy or Regal Cinemas, schooling at Mount Sion, to courting in John’s Park. These not only serve to record the idiosyncrasies of Waterford City but also the universality of experience that we can all relate to. Over the centuries, the people of Waterford have had to overcome everything from Anglo-Norman invaders and English conquerors to the Bubonic Plague and famine, while also trying to deal with, as Dunne wrote, a ‘Pearl of love, grit of pain’. The universality of human experience is the same even if the context of time and place are different. It’s a familiar story with different settings.

This book is Waterford City: A History and serves to explore the story of the city and its people, from poets and scholastic prelates to pop-stars and soccer players. It is very much a potted look at important events in the life of the city, encompassing Viking marauders to Anglo-Norman invaders and the development of Waterford’s economy and civic governance. Various figures and personalities are explored which have left an impact on the city and further afield. A history of any area and its people will have omissions or certain aspects perhaps not covered in the depth desired, but I hope, in the words written here, that the love of my city comes across. You, the reader, will be the judge of that.

1

VEDRAFJORDR:Viking Waterford

TIMELINE

853 CE: Charles Smith’s The Ancient and Present State of the County and City of Waterford notes that the foundation of Waterford by the Viking King Sitricus in CE 853.

914 CE: Deemed to be the most credible date for the foundation of Waterford by archaeologists and historians, with the Viking Ragnall establishing a longphort that formed the basis for Waterford City.

921 CE: Ragnall dies as the King of York and Waterford. He captured York (or Jorvik) the most significant city in the Viking world in CE 918.

1031 CE: Waterford is scorched to the ground. Six years later, the King of Leinster, Diarmuid Mac Maol na mBó, burnt the city in CE 1037. Just over fifty years later, in CE 1088, Waterford was destroyed by a fire started by the Vikings of Dublin.

1088 CE: A slaughtering of the Vikings who had settled at Waterford was carried out by the Irish and is detailed in The Annals of the Four Masters (which was compiled between 1632 and 1636).

1096 CE: Malchus is consecrated the first Bishop of Waterford by Anselm, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

1111 CE: Fire destroys Waterford, with the probable cause believed to be lighting.

1137 CE: The King of Leinster, Diarmuid Mac Murchadha, attempts to capture Waterford. Failing, he starts a fire which burns the city.

1170 CE: Waterford is captured by Richard de Clare, the Earl of Pembroke (also known as Strongbow). He marries the King of Leinster’s daughter Aoife in Christ Church Cathedral in the city.

Port Lairge. This is the ancient and present Irish name of the city of Waterford. It would appear to have derived this name from a Danish chieftain Lairge or Larac, or as the Danes write it Largo, who is mentioned in the Annals of the Four Masters at the year 951. The name Waterford or Vedrafiordr, was given it by the Danes; which is supposed to signify ‘weather bay.’

From The genealogy of Corca Laidhe (Author: Unknown), p.153

THE DANES OF WATERFORD

Like golden-belted bees about a hiveWhich come forever and forever goGoing and coming with the ebb and flow,From year to year, the strenuous Ostman strive.

Close in their billow-battling galleys prest,Backhands and forwards with the trusty tideThey sweep and wheel around the ocean wide,Like eagles swooping from their cliff-built nests.

And great their joy, returning where they leftTheir tricorned stronghold by the Suirshore’Mid song and feast, to tell their exploits o’er– Of all the helm-like glibs their swords had cleft,The black-haired damsels seized, the towers attacked.The still monastic cities they had sucked.

St John’s Manor House, 17 September 1874

VIKINGS: FROM RAIDERS TO SETTLERS,WOODSTOWN TO WATERFORD

The narrative of Waterford starts in the Viking Age, the period which saw Norse raiders plunder the island of Ireland from the eighth century and gradually settling by the eleventh century. First arriving in Ireland in 795, in the subsequent centuries the Vikings established what are today the island’s oldest cities and towns. The earliest archaeological level so far discovered in the modern city of Waterford dates to the eleventh century. However, an excavation carried out from 2003 to 2007 revealed a Viking settlement 9km west of the present city on the banks of the River Suir at Woodstown. Its discovery has prompted further theories into the foundation and development of Waterford.

It is not clear whether the Woodstown site was a short-lived raiding base or a more permanent settlement. More excavation is required, but so far over 6,000 artefacts have been discovered. Notable findings include balance-weights, a pagan-warrior burial and Kufic dirham (a ninth-century silver Arabic coin). The high amount of broken-up silver (known as hack-silver) suggests that the Vikings used Woodstown as a centre of trade. However, whether they were trading with their Irish neighbours or just with other Vikings still remains unclear.

Woodstown has been dated to the mid to late ninth century, possibly lasting until the beginning of the tenth century. The reason why it was abandoned is unclear, but it could have been because of another settlement downriver at Waterford. The historian Clare Downham believes:

the present site of Waterford may have been more easily defended … Waterford was closer to the estuaries of the Barrow and Nore … Waterford may have provided a better location for a quay than Woodstown.

There is not yet any archaeological evidence for any habitation at Waterford before the eleventh century, but historians and archaeologists have argued that it is likely there was early settlement around Reginald’s Tower and St John’s tributary. Earlier histories of the city have placed its foundation at 853, though this seems to be because Gerald of Wales asserts that three brothers, Amalavus, Sitricus and Ivarus, settled in Ireland and correspondingly established the cities of Dublin, Waterford and Limerick. Leaving aside the fact that Gerald was a Norman chronicler writing a couple of centuries later, the tale seems to be a neat foundation myth and Downham rejects its historical accuracy.

The foundation date of Waterford is placed at 914, when the Viking leader Ragnall arrived. Though he left Waterford for Dublin and then York to become a king on both sides of the Irish Sea, the Irish Annals reveal that there was constant settlement at Waterford after that date.

ALL IN THE NAME:VEDRAFJORDR, PORT LÁIRGE AND LOCH DÁ CHAECH

Waterford is the only Irish city to retain its Viking name, which is fitting for Ireland’s oldest continuous urban settlement. Waterford is older than most northern European capital cities (bar London and Paris). Furthermore, Waterford was Ireland’s second city after Dublin until the end of the seventeenth century.

Waterford was known to the Vikings as Veðrafjorðr, which is believed to mean the Fjord of Castrated Rams, or Windy Fjord. The latter meaning is related to the modern explanation of ‘Winter Haven’ and would tie in to the possibility that Waterford originated as a winter camp for the raiding Vikings who did not want to risk the stormy sea journey home.

The Irish name for Waterford, Port Láirge, means ‘Port of a Thigh’ with one explanation of the name coming from the Táin Bó Cúailnge (a tale from Irish mythology known as the Cattle Raid of Cooley) which tells of how the Brown Bull overcame his foe Findbennach, whose thigh-bone was thrown to Port Láirge. One more account comes from the pre-eleventh-century book Dindshenchas Érenn which details a young prince called Rot who dies at sea, torn apart by sirens, with his thigh-bone washed ashore at Port Láirge. From 915 to 918, the alternative name Loch dá Chaech was used for the Waterford harbour area, which translates as ‘the lake of the two-blind people’. However, the reason for this remains unclear.

In addition to the origin story told by Gerald of Wales, there is another one in the thirteenth-century biography of the Welsh king, Gruffudd ap Cynan. It claims that the Norwegian king, Harald Finehair, created Dublin and gave Waterford to his brother, whose descendants continued to rule the city. This era of Waterford’s history remains murky, but further archaeological excavation could provide more answers to this fascinating period.

VEDRAFJORDR:VIKING RULERS TO ANGLO-NORMAN CONQUERORS

Veðrafjǫrðr was a triangular-shaped settlement formed on a tidal inlet at the confluence of the Suir and St John’s rivers. It was defended by a fort named Dundory (deemed to have been where Reginald’s Tower stands today). Unfortunately, this did not stop the city being destroyed four times in 1031, 1037, 1088 and 1111. This Viking area had three main thoroughfares with High Street being the commercial hub of the city, while four smaller streets intersected the larger streets. Archaeological excavations in the 1980s and ’90s uncovered the remains of seventy-two sub-rectangular houses dating from the eleventh and twelfth centuries. These dwellings were constructed with wattle-and-daub walls and thatched roofs. A timber floor of a Viking Age ship was discovered in 1996 by archaeologist Orla Scully whilst excavating a quay wall on the Mall beside the present location of City Hall. The inhabitants of Waterford in the eleventh century were Hiberno-Norse, descendants of the Vikings who had intermarried with the indigenous Irish.

The advancement of the Uí Briain (O’Brien) family to power in Munster led to them ruling Waterford from 976. In 984, the city was the location for the meeting of the King of Munster Brian Boru (and later High King of Ireland) and the sons of Aralt, the Norse King of Limerick. Boru wanted a fleet from Limerick to assist his assault on Dublin, eventually taking place in 1014 at Clontarf. He received support from the Hiberno-Norse of Limerick and Waterford. Though Brian Boru died in battle, the Waterford group overpowered one of his rivals to the high kingship in Máel Sechnail. This defeat leads the historian Eamonn McEneaney to highlight ‘the importance of the port towns in Irish politics and the close relationship existing between the native population and the descendants of the original Viking settlers’. These towns had political significance, conferring wealth and status to the rulers who governed them.

The Marriage of Strongbow & Aoife by artist Daniel Maclise was painted in 1854 as an interpretation of a key moment in Irish history, which sees the narratives of Britain and Ireland entwined for centuries (photographic reproduction). National Gallery of Ireland

Waterford was starting to transfer allegiance from the kingdom of Munster to Leinster by the eleventh century. In 1037, the city was seized by Diarmait mac Máel na mBó, King of Uí Cheinnselaig (Kinsella); subsequently coins were minted in Waterford under his patronage.

Upon the death of mac Máel na mBó in 1072, Toirdelbach, the grandson of Brian Boru, took control of Leinster and realigned Waterford with Munster after assuming control of the city. He was later succeeded by his son Muirchertach in 1086, who became the most dominant king of Ireland, reigning as High King from 1093 to 1114. In 1088, Waterford was attacked in vain by a rival to the King of Leinster. Diarmait, brother of Muirchertach, was appointed ruler of Waterford in 1096. That same year, the Ostmen (people of mixed Gaelic and Norse ancestry and culture) of Waterford wanted a bishop to lead those who worshipped at buildings such as St Olaf’s. This led to Malchus being appointed the first bishop of Waterford that year. He managed to bring Christian practices in line with those of mainland Europe during his forty years in the position.

It is not apparent who succeeded Diarmait, who had deposed his brother in 1114 and died four years later. By 1137, Waterford was protected by King Cormac Mac Cárthaigh (McCarthy) of Desmond when confronted by the forces of Diarmait Mac Murchada of Leinster and Conchobar Ua Briain of Thomond. The western defences of Waterford had been strengthened with a stone wall replacing the timber palisade around the time of the attack.

The city remained under Mac Cárthaigh rule until 1170, when it was besieged by Raymond le Gros and the Anglo-Normans. In aiding the King of Leinster, Diarmait Mac Murchada, to regain his lost kingdom, the marcher lord Richard de Clare, better known as Strongbow, was promised the hand of Aoife, the king’s daughter, in marriage. The wedding took place at Christ Church in Waterford, heralding the end of the Viking Age in Ireland. Upon the death of the King of Leinster the following year, Henry II, King of England reached Waterford where he received the submission of Diarmait Mac Cárthaigh.

The Anglo-Norman invasion not only signaled the end of the Viking Age in Ireland but, with the marriage of Strongbow and Aoife, entwined the histories of Britain and Ireland for the centuries that follow.

Additionally, the Anglo-Normans altered the make-up of Irish towns with new defences, as well as introducing new customs and traits. The importance of the ceremony which took place in Christ Church is depicted in Daniel Maclise’s The Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife, painted in 1854. The oil painting was to be hung at the House of Lords in Westminster to mark the colonisation of the British Empire. The scene shows dead Irish warriors and a broken Celtic harp, while Strongbow stands on a damaged high cross as the old ways are destroyed by the Norman conquerors.

Eamonn McEneaney believes of the defeat of the Vikings in Ireland by the Anglo-Normans that:

It is ironic that the Vikings, founders of Ireland’s first towns, with their expertise in naval matters and improved weapons technology, should turn out to act as catalyst for the development of a more centralised Ireland, making it possible for the Anglo-Normans to achieve a foothold over a major part of the island in the decades after 1170.

TURGESIUS: NINTH-CENTURY VIKING RAIDER

Turgesius, after whom a tower which defended the city of Waterford was named, was a ninth-century Viking raider. Though historians are dubious of Turgesius existing, his Norse name was Thorgestr, with the Irish being Turgéis. He reached Dublin Bay with a large fleet in 837 and when he came to the mouth of the River Boyne took command of all Irish Vikings. The river system of Ireland allowed him to penetrate deeply into the island. Turgesius lay waste to Armagh in 841 and according to unreliable sources, possibly desecrated the altar of Clonmacnoise by making love to his wife Ota there in 844. He then declared her high priestess. The Viking invader drowned in Lough Owel in County Westmeath in 845.

KITE BROOCH:‘FINEST EXAMPLE OF VIKING-AGE METALWORK’

The Kite Brooch, weighing 20.6g, was crafted around 1090 and is considered one of the best examples of personal jewellery from the Viking Age, made from silver and adorned with gold foil and amethyst glass studs.

It was discovered by archaeologists during the excavations that coincided with the construction of the City Square Shopping Centre in Waterford City. Brooches were decorations on metal pins which would have been used to fasten a cloak and such implements were used until the early fourteenth century when buttons came into fashion. Such an elaborate brooch would have been worn by those of high status (men or women); only thirteen kite brooches survive in Ireland. Made of gold and silver, the Waterford Kite Brooch resembled a charcoal-like object when found by archaeologists, as silver attracts impurities.

The Waterford Kite Brooch is one of the most impressive examples of secular metalwork of the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries. It reflects indigenous Irish traditions with Scandinavian influences due to Waterford’s strong connections with the Vikings. Courtesy of Waterford Treasures

After months of conservation, the true beauty of the object became apparent and can now be clearly seen on display in Reginald’s Tower.

It is a fusion of Irish, English, Scandinavian and continental European designs. The Hiberno-Norse elements are indicative of Waterford in the twelfth century. The body of the brooch is a cast hollow silver kite-shaped box which would have been attached to a hinge and long pin to fasten the cloak. It appears that the goldsmith would have used a numerical plan by which to design the brooch. The length of the pin would have been longer than what is currently attached to the brooch. Even the length of pin would have been an indicator of a person’s status.

The Kite Brooch is a demonstration of the craftsmanship of those who inhabited Waterford around this time.

BUILDINGS WITH EARLY MEDIEVAL ORIGINS

Christ Church Cathedral:One of the Most Historic Sites in Ireland

In 1096, Waterford was granted its first bishop, though it is considered that the city’s first cathedral was not constructed until after 1152. The original cathedral predates the Anglo-Norman invasion of 1170 but was later refurbished in 1210. Christ Church Cathedral is where the marriage ceremony of Strongbow and Aoife took place. The significance of this event is that the histories of both Britain and Ireland were entwined for the next 800 years. The Anglo-Normans built a Gothic cathedral in the thirteenth century which was replaced by the present Christ Church Cathedral in the eighteenth century.

The Medieval cathedral had a central nave and chancel with aisles on either side, with a tower on one side. Over subsequent centuries, chapels were added. The archaeologist Dave Pollock reports that ‘[t]he floor level of the old cathedral is well below the present granite slabs. A decorated pier of the medieval building can be seen, standing on a mortar floor 1.8m down. The plain finish on the old floor may overlie paving or tiles.’

The current cathedral was designed by local architect John Roberts in the 1770s and contains parts of the old church from the early thirteenth century, such as the remains of an Anglo-Norman cluster of pillars. Legend has it that Bishop Chenevix was disinclined for the new cathedral to be built in a Georgian style, so it is believed that a ruse was devised to change his mind. Prospective builders organised that rubble would fall along the bishop’s path as he walked through the cathedral. After this, Chenevix believed that a new cathedral was essential. During the demolition, gunpowder was used to knock down the medieval cathedral.

Primarily made from limestone, the neo-Classical cathedral was finished in 1779, costing £5,397. Christ Church Cathedral encompasses an eight-bay double-height nave with a single-bay four-staged tower close towards the entrance. The original interior has changed from the eighteenth century due to a fire in the organ gallery in 1815. It was remodelled in 1891 by Sir Thomas Drew. This led to the ground floor windows being blocked out and the removal of square pews and galleries. There was also a construction of a new case for the organ.

The organ was restored in 2003 and moved to a new gallery in its original location. Commissioned in 1817, the Elliot organ was placed in the corner of Christ Church Cathedral post the late nineteenth-century refashioning of the church. The organ has a solid mahogany case encompassing gold-plated pipes. It is deemed one of the best organs on the island outside of Dublin. The cathedral also houses the gothic cadaver tomb of James Rice, Mayor of Waterford on eleven occasions during the fifteenth century. The tomb (which Rice shares with his wife Katherine Broun) was in a chapel built by Rice connected to the original Anglo-Norman cathedral. It has been moved twice in the Georgian cathedral and has been placed at its present location since 1880. The message of the tomb is illustrated by its Latin inscription which translates: ‘I am what you will be; I was what you are now.’

Reginald’s Tower:Ireland’s Oldest Urban Civic Building

Reginald’s tower – a massive hinge of stone connecting the two great outspread wings, the Quay and the Mall, within which lay the body of the city.

Thomas Francis Meagher, Recollections of Waterford (Easter Week 1843)

Reginald’s Tower and the Quay, Waterford, c. 1890 to c. 1900. Library of Congress

Ireland’s oldest urban civic building, Reginald’s Tower, appears to be named after the tenth-century Viking ruler of Waterford, Ragnall, or one of his successors bearing the same name. It seems that the Vikings had a fortification at this location from the tenth century. The tower was built to defend the entrance to Waterford, and the present structure was built in two stages. The ground and first floor were completed in the late twelfth century while the upper floors were constructed in the fifteenth century to accommodate the use of cannon.

The original access point to the tower is at the second storey, with there now being two entry points at ground-floor level. One of these later doorways (inserted into the tower in the 1590s) led to a sixteenth-century blockhouse where cannons were kept. The blockhouse was demolished in 1714. A cannonball is lodged in the top of the tower, dating from the siege of Waterford by the forces of Oliver Cromwell in 1650.

Reginald’s Tower and Poole’s Studios around 1910. A.H. Poole operated as a commercial photographer in the city from 1884 to 1954. His collection is housed in the National Library of Ireland and provides a fascinating insight into the social and economic state of Waterford of the period. Poole Collection WP0363, National Library of Ireland

Reginald’s Tower in the twenty-first century.

Inside the tower, the stumble steps or spiral stairs are built into the walls of the structure. These steps are intentionally set at different elevations to make them problematic for would-be aggressors to ascend. The fifty-six steps are angled to the right to make it hard for right-handed attackers to swing their swords. The walls at ground-floor level are almost 4m in thickness.