7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

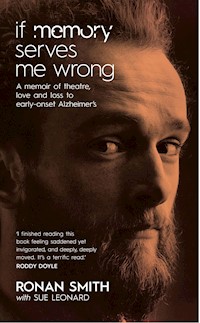

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

When Ronan Smith was in his twenties, his father, the theatre impresario Brendan Smith, developed obvious signs of early onset Alzheimer's disease but steadfastly refused to acknowledge it. Brendan ran the Olympia Theatre and had founded the Brendan Smith Academy of Acting and the Dublin Theatre Festival. A theatre and film actor, Ronan later became a producer and manager, and part of the worldwide phenomenon of Riverdance. It fell to Ronan to protect his father, and eventually, as Brendan's condition became more challenging, to commit him into care, a traumatic but pivotal event in their father-son relationship. So in 2014, when Ronan himself was diagnosed with the same illness, he knew exactly what the coming years would hold. But, unlike his father, Ronan chose to face his future positively, turning from work towards family, improving his diet and advocating for the Alzheimer Society of Ireland. In doing so, Ronan's radically different approach to this all-too-common disease has significantly changed the narrative around it in Ireland. Written in real time, If Memory Serves Me Wrong is a rare first-hand account of the experience of being both a family carer and of living with dementia. It is also a heartrending, sometimes harrowing and very often humorous memoir about the power of love in facing an uncertain future.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

IF MEMORY SERVES ME WRONG

First published in 2021 by

New Island Books

Glenshesk House

10 Richview Office Park

Clonskeagh

Dublin D14 V8C4

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © Ronan Smith, 2021

The right of Ronan Smith to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Print ISBN: 978-1-84840-807-4

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84840-808-1

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owners.

All effort has been made to seek permission to reproduce images, quotes and text herein. Any breaches, omissions or errors should be made known to the publisher directly.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

New Island Books is a member of Publishing Ireland.

To Miriam, Hannah and Loughlin, with deepest love.

DNA neither cares nor knows.DNA just is. And we dance to its music.—Richard Dawkins

CONTENTS

Foreword by Professor Ian Robertson

Prologue

One: A Day in Ronan’s Life: November 2019

Two: Beginnings

Three: Coming of Age

Four: Treading the Boards

Five: My Father Deteriorates

Six: Juggling

Seven: Miriam’s Story

Eight: One Chapter Closes

Nine: Acting Again

Ten: Riverdance

Eleven: The Pirate Queen

Twelve: Worrying Signs

Thirteen: Diagnosis

Fourteen: Coming to Terms

Fifteen: Rolling with the Punches

Sixteen: Trying to Live Positively

Seventeen: The Final Curtain

Eighteen: It’s a Wrap

Nineteen: A Day in Miriam’s Life: November 2020

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Ian Robertson, Emeritus Professor of Psychology in Trinity College Dublin and Co-Director of the Global Brain Health Institute

When Ronan Smith spoke to Gay Byrne on The Late Late Show in 1989 about his father Brendan’s Alzheimer’s disease, it was the first time that the closet doors of stigma and denial surrounding this disease had been thrown open so widely. Ronan’s pioneering leadership in the early years of the Alzheimer Society of Ireland (ASI), and his crucial work as an advocate for families afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease, are part of his proud and lasting legacy. When Ronan himself was diagnosed with the same, rare early-onset version of the disease as his father, that legacy grew as he used his intelligence, courage and commitment to resume his advocacy work, including as chair of the ASI’s Dementia Working Group.

At a time now where scarcely an Irish family is untouched by the illness, Ronan’s story of caring for his father, and then facing the same disease himself, could not be more timely. This book is unique and important because it tells the story of dementia from both sides, inside and out. But this is much more than a memoir about a very, very tough disease – it is also a tale of bravery, loyalty and love.

How, you might ask, could a book about Alzheimer’s disease be as beautiful, interesting and funny as it is hauntingly sad? Maybe only if it is written by two highly intelligent, insightful and empathic people trying their best to live with the hand that nature has dealt them. For this is as much a poignant love story as it is a tale of fate wielding its brutal club.

Ronan has early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, and his wife Miriam’s hilarious account of the unravelling of a blameless lie would on its own make this book worth reading for even the least dementia-interested reader. Instructing her producer and actor husband Ronan to tell a caller that she was in bed asleep, she ends up in a string of hilarious conundrums – theatrical farce as funny as the best that Dublin’s Gaiety Theatre ever presented.

The Olympia Theatre sits squarely centre-stage in this story. It is here that the young Ronan first has the awful realisation that his larger-than-life father – director of the Olympia and of the Dublin Theatre Festival – is unravelling chaotically in front of his eyes, brought low by Alzheimer’s disease. Hopelessly in denial, he is threatening to bring down the jewels of Dublin’s theatrical firmament with him. And it is in another Dublin theatre, The Gaiety, that Ronan finally retires from a career in Irish and international theatre that spanned the Abbey to Broadway, and The Pirate Queen to Riverdance.

With this rich and vibrant backdrop, you would want to read this story even if you had never heard of Alzheimer’s disease. But this is much, much more than the memoir of two remarkable thespians. The book lures you in because it is so well-written, interesting and funny. Then, softly but expertly, it punches you in the guts. It brings you face to face with what you shy away from because you dread it so much – your own dissolution.

This is a tale that is mythical and eternal, of great love tested by brute, biological reality. A rogue gene inherited from his father seeds Ronan’s brain with shards of toxic protein that gnaw at his day-to-day memory and steal his beautiful words.

Miriam’s voice interweaves with Ronan’s, a pure love haunted by illness and by the slow fading of her husband’s brilliance, her words becoming more pain-wracked yet ever more loving.

It is a sad truth that most of us will become characters in some version of a story like this, but there is hope on the horizon for the new treatments that will arrive for such diseases. Artificial intelligence, for example, has recently unfurled the mystery of how proteins fold. We can have hope – or even confidence – that eventually the rogue proteins in our brains can be packed away and forgotten.

But while we impatiently await these scientific advances, we need to better understand this disease and its impacts on families, to better support them and give them the quality of life they deserve. This unique book makes one giant step towards this goal, and we owe Ronan and Miriam a real debt of gratitude for their courage in writing it.

Prologue

It was my sixtieth birthday, and my wife had organised a party. I’d been expecting an intimate affair, but Miriam surprised me with a stay in the beautiful Tinakilly House Hotel in Co. Wicklow, where we were joined by ninety guests from all the different spheres of my life. Along with my children, Hannah and Loughlin, my brother Julian and his family, friends from college and some neighbours, there were many from the world of theatre – including a cluster who had acted with Miriam on RTÉ’s Glenroe. Some had travelled a great distance. I felt like the surprised guest on This Is Your Life.

Miriam had thought of everything. Wonderful tapas arrived throughout the evening, the wine flowed and the band played on. Two close friends spoke; Martin Drury gave me a eulogy – there is no other word for it – and Philip Lee gave a speech that doubled as a comic routine. When Hannah and Loughlin stood up and sang a song to me in harmony, I thought that the evening couldn’t get any better. But then it did.

The room darkened, and lights flashed as the sound of thunder slowly filled the room. As the sound rose, vibrating around us, we looked at each other in alarm, but then the double doors at the top of the room burst open, and in came a troupe of dancers, their feet taking up the drumming, thundery sound as they reached the recently constructed stage. It was the Riverdance Flying Squad, I realised. I stared at them open-mouthed, then I looked at Miriam, who was smiling broadly.

‘How?’ I asked. ‘When?’

Then John McColgan and Moya Doherty, the founders of Riverdance, whom I had worked with so closely over the years, tapped me on the shoulder and said, ‘Happy birthday, Ronan. This is our gift to you.’

When the male dancers had completed the ‘Thunderstorm’ routine they were joined by the females as they broke into ‘Riverdance’, the number that had taken the world by storm as the interval act of the Eurovision Song Contest in 1994. I must have watched that memorable performance hundreds of times when I was overseeing Riverdance’s many overseas productions, but such was the impact of those thirty dancers in this small room, it was as if I was seeing and hearing it for the first time. And judging from the emotion I witnessed on the faces of those around me, it was clear that my friends were finding the performance just as electrifying as I was.

‘You’re amazing,’ I said to Miriam as the performance drew to a close. ‘How did you plan that?’

‘With a lot of help,’ she said, indicating Julian Erskine, who had been lighting the performance from across the room. ‘He and I have been working on this for months. I couldn’t have done it without him.’

I smiled, delighted at this show of real friendship. Then Miriam took to the stage. I was amazed. Although she’s an excellent actor, Miriam is shy, and speaking in public is an ordeal for her. But she was wonderful. Starting out by thanking everyone, especially Julian Erskine, she then told a story.

When our children were seven and five, they’d come into our bed at weekends. And one morning Hannah, being a daddy’s girl, started telling Ronan how much she loved him. She went on and on and Ronan, who was loving this, asked her why. ‘Because you’re so tidy,’ she said. ‘And so neat. And so clever. And you work so hard.’

I tried not to ask the question, but I was feeling jealous and I couldn’t stop myself. I said, ‘Hannah, do you love Mummy?’

‘Um … um, yeah, I suppose.’

She didn’t sound so sure, so again, knowing I shouldn’t, I asked her why she loved me.

‘I don’t know.’ She furrowed her brow. Then, her face brightening, she said, ‘Yes I do! I know why. You make really good decisions.’

‘Do I?’

‘Yeah. You decided to marry Daddy.’

The room erupted into laughter. And then music came on, playing gently. It was Barry White singing ‘You’re the First, the Last, My Everything’, and over the music Miriam, turning, looked at me and said, ‘And Ronan, Hannah was right. I do make good decisions, and marrying you was the best one I ever made.’

I went up to her and we embraced. Then Hannah and Loughlin joined us in a group hug, and Miriam and I danced. And I thought I would burst with happiness.

As we sat relaxing by the fire in the small hours, I thought what a perfect night it had been; one I would look back on and remember for the rest of my life. And then, with a shock, I realised that I wouldn’t remember it. Not with my diagnosis. Not with my early-onset Alzheimer’s.

One

A Day in Ronan’s Life: November 2019

I wake early and have no idea what day it is. That’s not unusual – in fact it’s the case every morning now. Since I was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease in 2014, my short-term memory has been letting me down, and it’s getting worse. It’s the first area the illness attacks. I can remember things from my childhood, but cannot begin to recall what I did an hour and a half ago.

Leaving my wife Miriam to sleep a little longer, I get up and go out to the kitchen. I’ve missed the sunrise, but the morning light shimmers through the trees, lighting up Blessington Lake, which provides a pleasing contrast to the shadowy Wicklow hills on the horizon.

My first task of the day is to feed the hens, a job I love. There are currently six of them, of different varieties, including Rhode Island Red. Wild excitement breaks out, with lots of squawking, when I go into their quarter-acre pen and throw the corn. I collect the eggs, which are still warm to the touch. We used to have pigs – we had three and reared them for the freezer – but they were a lot of work, and around the time of my diagnosis we decided that we wouldn’t have them again.

Returning to the house, I make my breakfast. It’s always something hot. Sometimes I have beans on toast, or an egg, but today I fry up some bread, and put some tomatoes on the pan. I eat that with some goat’s cheese. It’s delicious.

I turn on the radio and listen to Morning Ireland. There’s been yet another murder in Dublin. The Gardaí suspect that it was carried out by a rival drug gang. When, at nine o’clock, Ryan Tubridy comes on, I listen to the introduction where he does a roundup of the day, then I switch off.

I make the coffee as Miriam walks through the door, yawning. This once-simple task is becoming confusing to me. It’s because my sequencing is breaking down.

‘It’s because there are so many stages involved in making coffee,’ explains Miriam. ‘You have to find the bag of coffee, then get out the pot. Then there’s the boiling water to think about, and the pot has to be opened and closed again.’

The process sounds so simple when she says it, but she’s right. I catch myself staring at the coffee grounds, wondering if I should spoon them straight into the cup. It can take time to figure out the lid of the pot. Today I manage it all, then go to the fridge for the milk. There’s another decision to be made. Should we have the protein milk, the soya or the almond?

While we drink our coffee, and Miriam tucks into her breakfast, we go through our diaries. There’s an entry in mine where I’ve written, ‘11.30 a.m: Martin Drury to visit’. He’s a close and loyal friend. Yesterday I had a meeting with the Dementia Working Group, as part of the Alzheimer Society of Ireland (ASI), in Brooks Hotel in Dublin. I’m chair of the group, which is made up of people who have the illness.

It’s important to me to contribute to the advocacy message, as it’s made a significant change in reducing stigma around the disease. When my father, the theatre impresario Brendan Smith, contracted Alzheimer’s there was shame around the issue and, perhaps as a consequence, he hid his illness and never acknowledged that there was anything wrong with him. It was a mistake, and one I am anxious not to repeat.

Many of the people attending the meeting were accompanied by carers, but I travelled in alone by bus. Miriam dropped me at the stop at Blessington. I made my way in without difficulty, I got off at the right bus stop and headed for Brooks Hotel but, for a moment, I hadn’t a clue where I was. It was very strange. I couldn’t orientate myself. The streetscape confused me, and standing there I thought, ‘Shit! I can’t find the hotel, but I know it’s somewhere around here.’

I stood there, gave myself time and worked out that it wasn’t down the road to my right, nor the one to my left, and by going straight I found my bearings again. The meeting was surprisingly good-humoured. Occasionally a new member will be full of anger, but yesterday was uplifting. There was much laughter as people vied to tell the best Alzheimer’s bad joke. When I arrived home, Miriam asked me what I’d done with my coat, and I realised I’d left it back there in the hotel.

After breakfast I call the dogs and go out for my morning walk. Bella, our young Cockapoo, is ready at once. She has been bouncing around my heels for some time, carrying a sock. But Pepsi, an old fella like me, who is deaf and I swear has dementia, is lying on a bed somewhere and has to be fetched.

Pepsi is a rescue dog who came to us when our son Loughlin was small, and he’s now at NCAD – the National College of Art and Design in Dublin. I start out, but have to return because I’ve forgotten Bella’s lead; then we make our way down, through a local farm to the beach at the lake’s edge. I love it there, gazing out as the dogs run around, playing. Bella jumps all over Pepsi and soon tires him out. I can spend an hour at a time there, thinking, taking in the scenery.

When I get home I make some green tea and go through to my office. I take my first tranche of pills. I’m on a cocktail of Alzheimer’s drugs that needs to be taken twice a day, and I’m currently also taking pills for my unsettled tummy. In an effort to counteract that, and to ease my nausea, I’m experimenting by eating little and often.

I’m very keen to stay active mentally as well as physically, and my writing project has become an obsession. Today I’m having trouble spelling words. That’s new – I normally don’t have to think about it – and I try to remember, determined not to ‘give in’ and look at a dictionary. I spend a minute or so toying with the word. It’s no good. I look the word up. That worries me, but I’ve learned from experience that it doesn’t necessarily mean I’ve lost that facility forever. Tomorrow I might have no difficulty with my spelling at all.

At eleven o’clock I make myself a snack. I have tomatoes and goat’s cheese in a bun. Miriam comes in and says, ‘You had the same for breakfast,’ and I tell her it’s healthy, so what’s the problem?

‘But Ronan, cheese is not great for your cholesterol. Remember, the doctor said to watch it?’

I don’t understand. ‘But I’m eating little and often.’

‘I know. But if you have more fat now, it will affect your high blood pressure.’

I get pissed off then. I can’t help it. But I give in, put the goat’s cheese aside, and eat the banana sandwich Miriam makes for me instead. Loughlin comes into the kitchen at that point. It’s his college holidays and he’s come home to help Miriam in the garden. He asks what we’re talking about.

‘Food,’ I say.

‘The other week your father made himself toast with Nutella on it,’ says Miriam. ‘Do you remember, Ronan?’

I nod. ‘Nothing wrong with Nutella.’

‘No. Except it was something you never used to eat. Oh, and you put tomato chutney on top of the Nutella.’

‘Dad – you didn’t! That’s gross!’

‘But it tasted good,’ I say.

Miriam laughs. ‘And then, last week, you had toast and chorizo and sardines – with raspberry jam on top.’

I shrug and say, ‘That’s one of the pluses of having Alzheimer’s, and there aren’t too many of those.’ I turn to my son. ‘I’m trying to be good. And my carer is pretty problematic, actually.’

We laugh. Well, you have to. It’s either that sometimes, or cry.

‘I think I’ll go back to my office until lunchtime,’ I say, turning to leave the kitchen.

‘But it’s 11.30,’ says Miriam.

I narrow my eyes questioningly.

‘Martin Drury is coming.’

‘Is he? Why didn’t you tell me?’

‘I did.’

It’s good to see Martin, who is full of theatre chat – telling me what our mutual friends are up to. We became close in college and have been friends and colleagues since, and I miss the world of the theatre. I can’t even remember when I last saw a play. I seem to have lost my appetite for it, as I have lost my appetite for so many things.

Martin goes before lunch and afterwards I take the dogs for a second walk, going up the road this time, to catch a better view. When I return, I decide to do a little gardening. Miriam is the expert – I’m just the commis gardener and do what I am told. I have to be careful now with machinery. I can use the sit-on mower because the engine turns off automatically when you climb off it, but I was using the push mower recently and misjudged things, putting my hand in to clear the blades when the machine was still running. I cut my finger badly and it took a good few visits to plastics in St James’s to sort it out. The nail has grown since, but I have to be honest with myself and accept my limitations. I now avoid anything mechanised. Today I weed the driveway by hand. I know I could spray weedkiller over it, but I find picking out the grass and weeds strangely meditative. I police the gravel, making it my business to keep it in check.

I spend a lot of the day looking for things that I’ve lost. I know this happens to everyone to some extent, but it’s magnified for me and can be extremely frustrating. I normally lose my glasses or my phone, but today it’s my wallet. Miriam and I have searched everywhere, and we can’t find it. Should we cancel my credit cards?

Simple tasks take me longer. Miriam says that I spend much too long in the kitchen, wiping the surfaces repeatedly, or running the tap over a spoon for ages before I put it in the dishwasher. I think I’m simply being thorough. When we’re going somewhere in the car, I get wired up gathering all my things together, making sure I have everything on Miriam’s checklist – the days are over when I can just leave the house without a thought.

When I first got the diagnosis, Miriam and I discussed how I could best fight the illness. Miriam explored ways to help slow the disease down and conducted research into diet and exercise for Alzheimer’s.

On her regime, I take as much exercise as possible. Miriam takes me to a local swimming pool twice or three times a week. I go hillwalking with a group sometimes, staying out for four or five hours. I cycle too, and Miriam is enrolling me on a badminton course for the autumn. It will be good for my coordination.

We decided to take on a ketogenic diet. It’s extremely healthy – we consume very little red meat. Tonight we eat fish, with organic spinach, courgettes and mangetout, picked fresh from the garden. These days I eat it in front of the six o’clock news. I don’t read a newspaper. I never really did, but I make sure to see the news every evening.

I’ve become a little bit obsessed with the whole Brexit thing. I find it just so alarming and extraordinary, and I’m gobsmacked at the behaviour of people. I still think there’s a possibility that Britain won’t leave the European Union. The fact that Boris Johnson only has one vote, it would be a very serious thing to take Britain out under those circumstances.

It’s a fine August evening, and I take a glass of red wine and walk up the garden to Miriam’s borders. It’s peaceful there, sitting on a bench. It’s like looking at a stage or perhaps at an audience, as the lawn falls away, and the view past the house to the water beyond is so beautiful. I sit, sip my wine and watch the clouds form shapes in that enormous expanse of sky, and I let my mind drift.

When I come in I watch some TV, but it’s hard these days to keep up. I can, mostly, follow a given episode of a drama, but I don’t remember what happened before this episode. It’s a very frustrating problem. And when there are sophisticated ruses to throw the audience off like, for example, in Peaky Blinders, I go, ‘Fuck!’ I just watch it and remember, vaguely, who all the characters are. Documentaries are easier to follow.

I read in bed every night before I settle to sleep. I find reading books easier than watching films and television, because I can always go back and check who people are and what has happened. I’ve recently read and enjoyed Colum McCann’s Let the Great World Spin and A Suitable Boy by Vikram Seth. I’m now reading a book by a woman who cared for her father, who had dementia.

I was cautious at first, but reading it has been fine, and very real and telling. It shows how awkward and awful the journey can be, but I already know that from dealing with my father. Still, I’m glad I started it, and am happy to continue to read it. I’m a little critical of some of the things she says, occasionally going, ‘No, I don’t think that’s right.’

I subscribe to National Geographic, and I love that. There’s such a range of subjects, and I’m interested in all the countries and issues the magazine covers. I appreciate the wonderful journalism produced by that organisation, and I like the fact that you can read a whole article with a beginning, a middle and an end. I love the experience of reading it and, though I can’t retain all I’ve read and know I won’t remember the half of it, I enjoy it at the time.

We’ve had to make a lot of adjustments as a couple since my diagnosis. Miriam is still my lover as well as my carer. We have to be careful to keep that balance and not drift apart in some effort to protect each other. I know she often feels upset. I hear her crying at night and do my best to comfort her.

I try not to despair. Ninety per cent of the time I manage to be reconciled to what has happened. None of this is my fault. I haven’t done anything wrong. The condition has arrived, and it is beginning to have an increasing impact. I have a certain understanding of the illness, but I’m not burdening myself with the facts. I sleep well, and if I wake in the night I have no trouble dropping off to sleep again.

Two

Beginnings

I can’t claim that I was close to my father; I barely knew him when I was a child. I was born in Dublin on 29 November 1957, two years after the arrival of my brother Julian. By this time both my parents, Brendan Smith and Beryl Fagan, were entirely committed to, and even obsessed with, professional theatre.

There were to be no other siblings – unless of course you count the most important one – namely the Dublin Theatre Festival, which was founded by my father in the same year that I was born. I have come to see it, superstitiously, as some sort of lifelong twin. Its fortunes, a little like mine, drifted up and down from year to year.

It was also a demanding child, claiming so much of my father’s time and energy that he was rarely in the house. He spent his days in the office and his evenings taking in a show. And when he was at home, he didn’t engage with Julian or me. He was distant and remote. I don’t think he knew quite what to do with us.

My mother was more of a presence in our lives. She was the one giving us affection and taking an interest in all that we did, but she shared with my father the glamour and excitement of the theatrical life. She was a professional actress with a particular love of musicals, and also a radio presenter.

As my childhood progressed and my father’s achievements, along with his status, began to grow, she was out with him on social engagements more and more. She also lent a hand in the Brendan Smith Theatre Academy, which my father had founded back in 1941.

Thanks partly to his childhood circumstances, theatre was in my father’s blood. In the early 1930s his mother, Greta Smith, started working at the Gate Theatre in Dublin, playing the cello during the half hour before the curtain rose to entertain the audience as it drifted in. Because she was a widow she needed the income from this, and a second job, in order to support herself and her two children.

This was the time of Hilton Edwards and Micheál Mac Liammóir, the eccentric but highly celebrated stars of Irish theatre who were based at the Gate Theatre. Audiences loved them, relishing the plays which were considered more exciting than the more conservative fare dished up by the Abbey Theatre. The two theatres were acknowledged rivals. A wit of the time referred to the two as Sodom and Begorrah.

My father attended Belvedere, a school geographically convenient to the Gate Theatre. The Jesuits had provided him with a charity scholarship, and he’d walk from the school to the Gate to be babysat by the house staff until his mother arrived from her other job. Hilton Edwards let my father sit beside him to watch rehearsals and auditions, and in that way he learned the basics of theatre from a highly skilled director in an entirely casual and unstructured way.

The Brendan Smith Theatre Academy had a senior and a junior section and, naturally enough, Julian and I were both enrolled into the children’s classes. I loved it – and got a tremendous buzz from performing – but Julian suffered there horribly. There’s a photograph of us taken at one of the Academy shows when I was about seven or eight years old, showing me dressed as an elf, and Julian as an Indian with a blacked-out face. I’m beaming from ear to ear, but poor Julian looks miserable. It was a terrible mistake, in my view, to foist the classes on him. Yet they persevered in making him attend. I can remember him saying to me later in life, ‘You came into the world as an actor.’ It was very clear that he did not.

But those were different times, and my father was keen that we should be given an opportunity to develop in something that was his passion. And back then, acting schools for kids were generally attended by a mix of children: those who loved performing, and those who were being made to go by ambitious parents. We went there every Saturday afternoon for classes, and we performed scenes from plays with regularity.

I also took part in some television and radio advertisements at a young age. In one advertisement I had to say, ‘Sometimes my mum flies off the handle.’ That was my line and, although I said it a tedious number of times, I didn’t know what it meant!

My mother employed a series of live-in housekeepers that came and went over the years of my childhood. She came from a comfortable middle-class background so the concept of paid help felt appropriate to her, but my friends found the setup strange. They’d come to play and say, ‘Who is this? It’s not your mum.’ And I’d have to explain.